CHAPTER 2

HISTORY OF COMPUTER CRIME

M. E. Kabay

2.1 WHY STUDY HISTORICAL RECORDS?

2.3.1 Direct Damage to Computer Centers

2.3.2 1970–1972: Albert the Saboteur

2.4.1 1970: Jerry Neal Schneider

2.4.2 1980–2003: Kevin Mitnick

2.5.2 1982–1991: Kevin Poulsen

2.6.1 Equity Funding Fraud (1964–1973)

2.6.2 1994: Vladimir Levin and the Citibank Heist

2.10.2 Scrambler, 12-Tricks and PC Cyborg

2.10.3 1994: Datacomp Hardware Trojan

2.10.6 Hardware Trojans and Information Warfare

2.11 NOTORIOUS WORMS AND VIRUSES

2.11.1 1970–1990: Early Malware Outbreaks

2.11.2 December 1987: Christmas Tree Worm

2.11.3 November 2, 1988: Morris Worm

2.12.1 1994: Green Card Lottery Spam

2.14 HACKER UNDERGROUND OF THE 1980S AND 1990S

2.14.1 1981: Chaos Computer Club

2.14.3 1984: Cult of the Dead Cow

2.14.4 1984: 2600: The Hacker Quarterly

2.14.7 1989: Masters of Deception

2.14.8 1990: Operation Sundevil

2.14.9 1990: Steve Jackson Games

2.14.10 1992: L0pht Heavy Industries

2.1 WHY STUDY HISTORICAL RECORDS?

Every field of study and expertise develops a common body of knowledge that distinguishes professionals from amateurs. One element of that body of knowledge is a shared history of significant events that have shaped the development of the field. Newcomers to the field benefit from learning the names and significant events associated with their field so that they can understand references from more senior people in the profession, and so that they can put new events and patterns into perspective. This chapter provides a brief overview of some of the more famous (or notorious) cases of computer crime (including those targeting computers and those mediated through computers) of the last four decades.1

2.2 OVERVIEW.

This chapter illustrates several general trends from the 1960s through the decade following 2000:

- In the early decades of modern information technology (IT), computer crimes were largely committed by individual disgruntled and dishonest employees.

- Physical damage to computer systems was a prominent threat until the 1980s.

- Criminals often used authorized access to subvert security systems as they modified data for financial gain or destroyed data for revenge.

- Early attacks on telecommunications systems in the 1960s led to subversion of the long-distance phone systems for amusement and for theft of services.

- As telecommunications technology spread throughout the IT world, hobbyists with criminal tendencies learned to penetrate systems and networks.

- Programmers in the 1980s began writing malicious software, including self-replicating programs, to interfere with personal computers.

- As the Internet increased access to increasing numbers of systems worldwide, criminals used unauthorized access to poorly protected systems for vandalism, political action, and financial gain.

- As the 1990s progressed, financial crime using penetration and subversion of computer systems increased.

- The types of malware shifted during the 1990s, taking advantage of new vulnerabilities and dying out as operating systems were strengthened, only to succumb to new attack vectors.

- Illegitimate applications of e-mail grew rapidly from the mid-1990s onward, generating torrents of unsolicited commercial and fraudulent e-mail.

2.3 1960S AND 1970S: SABOTAGE.

Early computer crimes often involved physical damage to computer systems and subversion of the long-distance telephone networks.

2.3.1 Direct Damage to Computer Centers.

In February 1969, the largest student riot in Canada was set off when police were called in to put an end to a student occupation of several floors of the Hall Building. The students had been protesting against a professor accused of racism, and when the police came in, a fire broke out and computer data and university property were destroyed. The damages totalled $2 million, and 97 people were arrested.2

Thomas Whiteside cataloged a litany of early physical attacks on computer systems in the 1960s and 1970s:3

| 1968 | Olympia, WA: An IBM 1401 in the state is shot twice by a pistol-toting intruder |

| 1970 | University of Wisconsin: Bomb kills one and injures three people and destroys $16 million of computer data stored on site |

| 1970 | Fresno State College: Molotov cocktail causes $1 million damage to computer system |

| 1970 | New York University: Radical students place fire-bombs on top of Atomic Energy Commission computer in attempt to free a jailed Black Panther |

| 1972 | Johannesburg, South Africa: Municipal computer is dented by four bullets fired through a window |

| 1972 | New York: Magnetic core in Honeywell computer attacked by someone with a sharp instrument, causing $589,000 of damage |

| 1973 | Melbourne, Australia: Antiwar protesters shoot American firm's computer with double-barreled shotgun |

| 1974 | Charlotte, NC: Charlotte Liberty Mutual Life Insurance Company computer is shot by a frustrated operator |

| 1974 | Dayton, OH: Wright Patterson Air Force Base: Four attempts are made to sabotage computers, including by magnets, loosened wires, and gouges in equipment |

| 1977 | Rome, Italy: Four terrorists pour gasoline on university computer and burn it to cinders |

| 1978 | Lompoc, CA: Vandenburg Air Force Base:: A peace activist destroys an unused IBM 3031 using a hammer, a crowbar, a bolt cutter, and a cordless power drill as a protest against the NAVSTAR satellite navigation system, claiming it gives the United States a first-strike capability |

The incidents of physical abuse of computer systems did not stop as other forms of computer crime increased. For example, in 2001, NewsScan editors4 summarized a report from Wired Magazine:

A survey by British PC maker Novatech, intended to take a lighthearted look at techno-glitches, instead revealed the darker side of computing. One in every four computers has been physically assaulted by its owner, according to the 4,200 respondents.5

In April 2003, the National Information Protection Center and Department of Homeland Security reported:

Nothing brings a network to a halt more easily and quickly than physical damage. Yet as data transmission becomes the lifeblood of Corporate America, most big companies haven't performed due diligence to determine how damage-proof their data lifelines really are. Only 20 percent of midsize and large companies have seriously sussed out what happens to their data connections after they go beyond the company firewall, says Peter Salus of MatrixNetSystems, a network-optimization company based in Austin, TX.6

By the mid-2000s, concerns over the physical security of electronic voting systems had risen to public awareness. For example:

A cart of Diebold electronic voting machines was delivered today to the common room of this Berkeley, CA boarding house, which will be a polling place on Tuesday's primary election. The machines are on a cart which is wrapped in plastic wrap (the same as the stuff we use in the kitchen). A few cable locks (bicycle locks, it seems) provide the appearance of physical security, but they aren't threaded through each machine. Moreover, someone fiddling with the cable locks, I am told, announced after less than a minute of fiddling that he had found the three-digit combination to be the same small integer repeated three times.7

2.3.2 1970–1972: Albert the Saboteur.

One of the most instructive early cases of computer sabotage occurred at the National Farmers Union Service Corporation of Denver, where a Burroughs B3500 computer suffered 56 disk head crashes in the two years from 1970 to 1972. Down time was as long as 24 hours per crash, with an average of 8 hours per incident. Burroughs experts were flown in from all over the United States at one time or another, and concluded that the crashes must be due to power fluctuations.

By the time all the equipment had been repaired and new wiring, motor generators, circuit breakers, and power-line monitors had been installed in the computer room, total expenditures for hardware and construction were over $500,000 (in 1970 dollars). Total expenses related to down time and lost business opportunities because of delays in providing management with timely information are not included in this figure. In any case, after all this expense, the crashes continued sporadically as before.

By this time, the experts were beginning to wonder about their analysis. For one thing, all the crashes had occurred at night. Could it be sabotage? Surely not! Old Albert, the night-shift operator, had been so helpful over all these years; he had unfailingly called in the crashes at once, gone out for coffee and donuts for the repair crews, and been meticulous in noting the exact times and conditions of each crash. However, all the crashes had in fact occurred on his shift.

Management installed a closed-circuit television (CCTV) camera in the computer room—without informing Albert. For some days, nothing happened. Then one night another crash occurred. On the CCTV monitor, security guards saw good ol' Albert open up a disk cabinet and poke his car key into the read/write head solenoid, shorting it out and causing the 57th head crash.

The next morning, management confronted Albert with the film of his actions and asked for an explanation. Albert broke down in mingled shame and relief. He confessed to an overpowering urge to shut the computer down. Psychological investigation determined that Albert, who had been allowed to work night shifts for years without a change, had simply become lonely. He arrived just as everyone else was leaving; he left as everyone else was arriving. Hours and days would go by without the slightest human interaction. He never took courses, never participated in committees, never felt involved with others in his company. When the first head crashes occurred—spontaneously—he had been surprised and excited by the arrival of the repair crew. He had felt useful, bustling about, telling them what had happened. When the crashes had become less frequent, he had involuntarily, and almost unconsciously, re-created the friendly atmosphere of a crisis team. He had destroyed disk drives because he needed company.8

2.4 IMPERSONATION.

Using the insignia and specialized language of officials as part of social engineering has a long history in crime; a dramatization of these techniques is in the popular movie Catch Me If You Can9 about Frank William Abagnale Jr., the teenage scammer and counterfeiter who pretended to be a pilot, a doctor, and a prosecutor before eventually becoming a major contributor to the U.S. government's anticounterfeiting efforts and then founding a major security firm.10

Several criminals involved in computer-mediated or computer-oriented crime be-came notorious for using impersonation.

2.4.1 1970: Jerry Neal Schneider.

A notorious computer-related crime started in 1970, when teenager Jerry Neal Schneider used Dumpster diving to retrieve printouts from the Pacific Telephone and Telegraph (PT&T) company in Los Angeles. After years of collection, he had enough knowledge of procedures that he was able to impersonate company personnel on the phone. He collected yet more detailed information on procedures. Posing as a freelance magazine writer, he even got a tour of the computerized warehouse and information about ordering procedures. In June 1971, he ordered $30,000 of equipment to be sent to a normal PT&T dropoff point—and promptly stole it and sold it. He eventually had a 6,000-square-foot warehouse and 10 employees. He stole over $1 million of equipment—and sold some of it back to PT&T. He was finally denounced by one of his own disgruntled employees and became a computer security consultant after his prison term.11

2.4.2 1980–2003: Kevin Mitnick.

Born in 1963, Kevin Mitnick became involved in crime early, using a special punch for bus transfers to get free rides anywhere in the San Fernando Valley in California by the time he was a young teenager. His own autobiographical comments show him to have been involved in phone phreaking, malicious pranks, and breaking into computers at the Digital Equipment Corporation (DEC) using social engineering.12

In 1981, he and his friend Lewis De Payne used social engineering to gain unauthorized access to an operations center for Pacific Bell; “the juvenile court ordered a diagnostic psychological study of Mitnick and sentenced him to a year's probation.”13 In 1987, he was arrested for breaking into the computers of the Santa Cruz Operation, makers of SCO UNIX, and sentenced to three years probation.

In the summer of 1988, Mitnick and his accomplice and friend Lenny DiCicco cracked the University of Southern California computers again and misappropriated hundreds of Mb of disk space (a lot at the time) to store VAX VMS source files stolen from Digital Equipment Corporation (DEC). Mitnick was arrested by the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) for having stolen the VAX VMS source code. During his trial, he was described as suffering from an impulse-control disorder. In July 1989, he was sentenced to a year in jail and six months rehabilitation. He later tried to become a private investigator and security specialist. He was generally treated with hostility by the established information security community.

In November 1992, Mitnick went underground again when the FBI got a warrant for his arrest on charges of stealing computer time from a phone company. He was located two years later when he made the mistake of leaving insulting messages on the computer and voice-mail systems of a physicist and Internet security expert Tsutomu Shimomura. Shimomura was so irritated that he helped law enforcement authorities track the fugitive to North Carolina, where Mitnick was arrested in February 1995 and imprisoned pending trial.

Mitnick was convicted in federal court for the Central District of California on August 9, 1999, and sentenced to 46 months imprisonment for “four counts of wire fraud, two counts of computer fraud and one count of illegally intercepting a wire communication.”14 Mitnick was previously sentenced by Judge Pfaelzer to an additional 22 months in prison, this for possessing cloned cellular phones when he was arrested in North Carolina in 1995, and for violating terms of his supervised release imposed after being convicted of an unrelated computer fraud in 1989. He admitted to violating the terms of supervised release by hacking into PacBell voicemail and other systems, and to associating with known computer hackers, in this case codefendant Louis De Payne. Following his release from prison in September 2000, Mitnick was to be on three years parole during which his access to computers was restricted15 and his profits from writing or speaking about his criminal career were to be turned over to reimburse his victims.

Mitnick earned a living on the talk circuit and eventually founded his own security consulting firm. In the years since his release from prison, he has collaborated in writing several books on social engineering.16

Perhaps his most significant position in the history of computer crime is that he became an icon in the criminal underground. “FREE KEVIN” was a popular component of Web vandalism for many years, and Eric Corley, the longtime editor of the criminal-hacking publication 2600: The Hacker Quarterly, even made a movie, Freedom Downtime, about what the criminal underground describes as the grossly unfair treatment of Mitnick by the federal government and the news media.17

2.4.3 Credit Card Fraud.

Credit at local businesses dates back into the undocumented past.18 In the United States, credit cards appeared in the mid-1920s when gasoline companies began issuing cards that were recognized at stations across the country.19 In 1950, Frank X. McNamara started the Diners Club, the first credit card company serving multiple types of businesses; the company began the practice of charging a percentage fee for each transaction and also charged its clients a membership fee.20 The VISA card evolved from the 1951 BankAmericard from the Bank of America, and a consortium of California banks established MasterCard shortly thereafter. American Express started its card program in 1958.

Card use rose and, unsurprisingly, credit card fraud was rampant. Mail theft also became widespread as unscrupulous individuals discovered that envelopes containing credit cards were just like envelopes full of cash. And there was little to stop card companies from sending out cards that customers had never asked for, were not expecting, and could not have known had been stolen, until the issuing company began demanding payment for the charges that had been run up. These crimes and other problems stemming from the relentless card-pushing by banks led directly to the passage of the Fair Credit Billing Act of 197421 as well as many other laws22 designed to protect the consumer.23

By the mid-1990s, credit card fraud was a rapidly growing problem for consumers and for law enforcement. A 1997 FBI report stated:

Around the world, bank card fraud losses to Visa and Master-Card alone have increased from $110 million in 1980 to an estimated $1.63 billion in 1995….The United States has suffered the bulk of these losses-approximately $875 million for 1995 alone. This is not surprising because 71 percent of all worldwide revolving credit cards in circulation were issued in this country…. Law enforcement authorities continually confront new and complex schemes involving credit card frauds committed against financial institutions and bank card companies. Perpetrators run the gamut from individuals with easy access to credit card information-such as credit agency officials, airline baggage handlers, and mail carriers, both public and private, to organized groups, usually from similar ethnic backgrounds, involved in large-scale card theft, manipulation, and counterfeiting activities. Although current bank card fraud operations are numerous and varied, several schemes account for the majority of the industry's losses by taking advantage of dated technology, customer negligence, and laws peculiar to the industry.24

2.4.4 Identity Theft Rises.

By the late 1990s and in the decade following the year 2000, credit-card fraud was subsumed into the broader category of identity theft. Instead of limiting their depredations to running up bills on stolen or forged credit card accounts, thieves, often in organized rings, created entire bogus parallel identities, initiating unpaid bank loans, buying cars with other people's credit, and wreaking havoc with innocent victims' credit ratings, financial situations, and even their daily life. Victims of extreme cases lost their ability to obtain mortgages, buy new homes, and accept new jobs. Worse, the burden of proof of innocence fell on the victims, in a bitter reversal of the assumption of innocence underlying British common law and its offshoot in the commonwealth and the United States.

At the time of this writing (May 2008), identity theft is the fastest-growing form of fraud today. The National Crime Victimization Survey (NCVS) of the U.S. Department of Justice Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS) includes surveys dating back to 1973. Currently the random sample includes 77,200 households with 134,000 in all who are contacted every six months and followed for three years. The results for 2005 are available from the BJS Web site as PDF reports and as ZIP files containing spreadsheets for further analysis.25

A summary of that research26 reports that about 6.4 million households (5.5 percent of all the households in the United States) had been affected by some form of identity theft (defined as theft of credit cards, thefts from existing bank accounts, misuse of personal information, or multiple types of theft at same time). Losses from credit-card theft averaged $980 per household; across all type of theft, the average was $1,620 per household; and for misuse of personal information the losses averaged $4,850 per household. The most likely victim households were headed by people between 18 and 24 years of age; households with family incomes above $75,000 were twice as likely to be victimized as those whose annual income was less than $50,000.

In August, 2008, the U.S. Department of Justice announced27 the single largest and most complex case of identity theft ever charged in this country. It involved eleven people from five different countries, including two from the U.S. and two from the Peoples Republic of China, who had stolen more than 40,000,000 credit card records from a major U.S. retailer. They drove by, or loitered at, buildings in which wireless networks were housed, and installed sniffers that recorded passwords, card numbers and account data. Unless adequate preventative measures are installed quickly, more such horrendous events will be sure to occur. For more on wireless network security, see Chapter 33 in this Handbook.

2.5 PHONE PHREAKING.

Even in the earliest days of telephony, teenage boys played with the new technology to cause havoc. In the late 1870s, the new AT&T system in America had to stop using teenagers as switchboard operators:

The boys were openly rude to customers. They talked back to subscribers, saucing off, uttering facetious remarks, and generally giving lip. The rascals took Saint Patrick's Day off without permission. And worst of all they played clever tricks with the switchboard plugs: disconnecting calls, crossing lines so that customers found themselves talking to strangers, and so forth.

This combination of power, technical mastery, and effective anonymity seemed to act like catnip on teenage boys.28

2.5.1 2600 Hz.

In the late 1950s, AT&T began switching its telephone networks to direct-dial long distance, using specific frequency tones to communicate among its switches. Around 1957, a blind seven-year-old child named Josef Engressia with perfect pitch and an emotional fixation on telephones learned to whistle the 2600-Hz pitch that interrupted long-distance telephone calls and allowed him to place a free long-distance call to anywhere in the world.29 This emotionally disturbed person eventually renamed himself “Joybubbles” and is often described as the founder of phone phreaking—the manipulation of the phone system for unauthorized access to services.

John Draper was in the U.S. Air Force in 1964 when he began helping his colleagues place free phone calls. At the suggestion of Joybubbles, he used the whistles in Cap'n Crunch cereal boxes to generate the 2600-Hz tone and then, calling himself Captain Crunch, went on to create electronic tone synthesizers called blue boxes.30 In the 1970s, Apple founders Steve Wozniak and Steve Jobs built blue boxes and, using the devices, perpetrated such pranks as calling the Vatican while pretending to be Henry Kissinger.31

A significant contributor to the growth of phreaking in the 1970s was the publication in 1971 of an article about phreaking in Esquire Magazine, which attracted the attention of many young technophiles.32

2.5.2 1982–1991: Kevin Poulsen.

As the phone system shifted to greater reliance on computers, the border between phreaking and hacking began to blur. One of the important names from the 1980s period of fascination with everything phone-related was Kevin Poulsen.

Kevin Poulsen's autobiographical sketch is shown next.

Kevin Poulsen first gained notoriety in 1982, when the Los Angeles County District Attorney's Office raided him for gaining unauthorized access to a dozen computers on the ARPANET, the forerunner of the modern Internet. Seventeen years old at the time, he was not charged, and went on to work as a programmer and computer security supervisor for SRI International in Menlo Park, California, then as a network administrator at Sun Microsystems.

In 1987, Pacific Bell security agents discovered that Poulsen and his friends had been penetrating telephone company computers and buildings. After learning that Poulsen had also worked for a defense contractor where he'd held a SECRET level security clearance, the FBI began building an espionage case against the hacker.

Confronted with the prospect of being held without bail, Poulsen became a fugitive. While on the run, he obtained information on the FBI's electronic surveillance methods, and supported himself by hacking into Pacific Bell computers to cheat at radio-station phone-in contests, winning a vacation to Hawaii and a Porsche 944-S2 Cabriolet in the process.

After surviving two appearances on NBC's Unsolved Mysteries, Poulsen was finally captured on April 10th, 1991, in a Van Nuys grocery store, by a Pacific Bell security agent acting on an informant's tip. On December 4th, 1992, Poulsen became the first hacker to be indicted under U.S. espionage laws when the Justice Department charged him with stealing classified information. (18 U.S.C. 793).

Poulsen was held without bail while he vigorously fought the espionage charge. The charge was dismissed on March 18th, 1996.

Poulsen served five years, two months, on a 71 month sentence for the crimes he committed as a fugitive, and the phone hacking that began his case. He was freed June 4th, 1996, and began a three year period of supervised release, barred from owning a computer for the first year, and banned from the Internet for the next year and a half.

Since his release, Poulsen has appeared on MSNBC, and on ABC's Nightline, and he was the subject of Jon Littman's flawed book, “The Watchman—the Twisted Life and Crimes of Serial Hacker Kevin Poulsen.” His case has earned mention in several computer security and infowar tracts—most of which still report that he broke into military computers and stole classified documents.33

After his release from prison, Kevin Poulsen turned to journalism. He became an editor for Security Focus and then was hired as a senior editor at Wired News. He is a serious investigative reporter (e.g., he broke the story of sexual predators in MySpace)34 and a frequent contributor to the “Threat Level” blog.35

2.6 DATA DIDDLING.

One of the most common forms of computer crime since the start of electronic data processing is data diddling—illegal or unauthorized data alteration. These changes can occur before and during data input, or before output. Data-diddling cases have included bank records, payrolls, inventory data, credit records, school transcripts, telephone switch configurations, and virtually all other applications of data processing.

2.6.1 Equity Funding Fraud (1964–1973).

One of the classic early data-diddling frauds was the Equity Funding case, which began with computer problems at the Equity Funding Corporation of America, a publicly traded and highly successful firm with a bright idea. The idea was that investors would buy insurance policies from the company and also invest in mutual funds at the same time, with profits to be redistributed to clients and to stockholders. Through the late 1960s, Equity's shares rose dizzyingly in price, and there were news magazine stories about this wunderkind of the Los Angeles business community.

The computer problems occurred just before the close of the financial year in 1964. An annual report was about to be printed, yet the final figures simply could not be extracted from the mainframe. In despair, the head of data processing told the president the bad news; the report would have to be delayed. Nonsense, said the president expansively (in the movie, anyway); simply make up the bottom line to show about $10 million in profits and calculate the other figures so it would come out that way. With trepidation, the DP chief obliged. He seemed to rationalize it with the thought that it was just a temporary expedient, and could be put to rights later in the real financial books.

The expected profit did not materialize, and some months later, it occurred to the executives at Equity that they could keep the stock price high by manufacturing false insurance policies that would make the company look good to investors. They therefore began inserting false information about nonexistent policyholders into the computerized records used to calculate the financial health of Equity.

In time, Equity's corporate staff got even greedier. Not content with jacking up the price of their stock, they decided to sell the policies to other insurance companies via the redistribution system known as reinsurance. Reinsurance companies pay money for policies they buy and spread the risk by selling parts of the liability to other insurance companies. At the end of the first year, the issuing insurance companies have to pay the reinsurers part of the premiums paid in by the policyholders. So in the first year, selling imaginary policies to the reinsurers brought in large amounts of real cash. However, when the premiums came due, the Equity crew “killed” imaginary policyholders with heart attacks, car accidents, and, in one memorable case, cancer of the uterus—in a male imaginary policyholder.

By late 1972, the head of DP calculated that by the end of the decade, at this rate, Equity Funding would have insured the entire population of the world. Its assets would surpass the gross national product of the planet. The president merely insisted that this showed how well the company was doing.

The scheme fell apart when an angry operator who had to work overtime told the authorities about shenanigans at Equity. Rumors spread throughout Wall Street and the insurance industry. Within days, the Securities and Exchange Commission had informed the California Insurance Department that they had received information about the ultimate form of data diddling: Tapes were being erased. The officers of the company were arrested, tried, and condemned to prison terms.36

2.6.2 1994: Vladimir Levin and the Citibank Heist.

In February 1998, Vladimir Levin was sentenced to three years in prison by a court in New York City. Levin masterminded a major conspiracy in 1994 in which the gang illegally transferred $12 million in assets from Citibank to a number of international bank accounts. The crime was spotted after the first $400,000 was stolen in July 1994, and Citibank cooperated with the FBI and Interpol to track down the criminals. Levin was ordered to pay back $240,000, the amount he actually managed to withdraw before he was arrested.37 The incident led to Citibank's hiring of Stephen R. Katz as the banking industry's first chief information security officer (CISO).

2.7 SALAMI FRAUD.

In the salami technique, criminals steal money or resources a bit at a time. Two different etymologies are circulating about the origins of this term. One school of security specialists claim that it refers to slicing the data thin—like a salami. Others argue that it means building up a significant object or amount from tiny scraps—like a salami.

There were documented cases of salami frauds in the 1970s and 1980s, but one of the more striking incidents came to light in January 1993, when four executives of a Value Rent-a-Car franchise in Florida were charged with defrauding at least 47,000 customers using a salami technique. The federal grand jury in Fort Lauderdale claimed that the defendants modified a computer billing program to add five extra gallons to the actual gas tank capacity of their vehicles. From 1988 through 1991, every customer who returned a car without topping it off ended up paying inflated rates for an inflated total of gasoline. The thefts ranged from $2 to $15 per customer—rather thick slices of salami but nonetheless difficult for the victims to detect.

Unfortunately, salami attacks are designed to be difficult to detect. The only hope is that random audits, especially of financial data, will pick up a pattern of discrepancies and lead to discovery. As any accountant will warn, even a tiny error must be tracked down, since it may indicate a much larger problem. For example, Cliff Stoll's famous adventures tracking down spies in the Internet began with an unexplained $0.75 discrepancy between two different resource accounting systems on UNIX computers at the Keck Observatory of the Lawrence Berkeley Laboratories. Stoll's determination to understand how the problem could have occurred revealed an unknown user; investigation led to the discovery that resource-accounting records were being modified to remove evidence of system use. The rest of the story is told in Clifford Stoll's book The Cuckoo's Egg.

2.8 LOGIC BOMBS.

A logic bomb is a program that has deliberately been written or modified to produce results when certain conditions are met that are unexpected and unauthorized by legitimate users or owners of the software. Logic bombs may be within standalone programs, or they may be part of worms (programs that hide their existence and spread copies of themselves within a computer systems and through networks) or viruses (programs or code segments which hide within other programs and spread copies of themselves).

Time bombs are a subclass of logic bombs that “explode” at a certain time.

According to a National Security Council employee, the United States government authorized insertion of a time bomb in software to control the Trans-Siberian natural gas pipeline that they knew would be stolen from U.S. sources by the Soviet government. “The result was the most monumental non-nuclear explosion and fire ever seen from space,” said Thomas C. Reed.38

The infamous Jerusalem virus (also known as the Friday the 13th virus) of 1988 was a time bomb. It duplicated itself every Friday and on the thirteenth of the month, causing system slowdown; on every Friday the 13th after May 13, 1988, it also corrupted all available disks on the infected systems.

Other examples of notorious time bombs include:

- A common PC virus from the 1980s, Cascade, made all the characters fall to the last row of the display during the last three months of every year.

- The Michelangelo virus of 1992 was designed to damage hard disk directories on the sixth of March every year.

- In 1992, computer programmer Michael Lauffenburger was fined $5,000 for leaving a logic bomb at General Dynamics. His intention was to return after his program had erased critical data and be paid to fix the problem.39

The most famous time bomb of recent years was the Y2K (year 2000) problem. In brief, old programs used two-digit year codes that were based on the assumption that they applied to the twentieth century. As the twenty-first century approached, analysts warned of catastrophic consequences if the programs were not corrected to use four-digit years or otherwise adapt to the change of century.40 In the event, the corrective measures worked and there were no disasters. Later analysis showed a positive correlation between investments in Y2K remediation and later profitability.41

2.9 EXTORTION.

Computer data can be held for ransom. For example, according to Whiteside, in 1971, two reels of magnetic tape belonging to a branch of the Bank of America were stolen at Los Angeles International Airport. The thieves demanded money for their return. The owners ignored the threat of destruction because they had adequate backup copies.

Other early cases of extortion involving computers:

- In 1973, a West German computer operator stole 22 tapes and received $200,000 for their return. The victim did not have adequate backups.

- In 1977, a programmer in the Rotterdam offices of Imperial Chemical Industries, Ltd. (ICI) stole all his employer's tapes, including backups. Luckily, ICI informed Interpol of the extortion attempt. As a result of the company's forthrightness, the thief and an accomplice were arrested in London by officers from Scotland Yard.

In the 1990s, one of the most notorious cases of extortion was the 1999 theft of 300,000 records of customer credit cards from the CD Universe Web site by “Maxus,” a 19-year-old Russian. He sent an extortion note that read: “Pay me $100,000 and I'll fix your bugs and forget about your shop forever…or I'll sell your cards [customer credit data] and tell about this incident in news.” Refused by CD Universe owners, he promptly released 25,000 credit card numbers via a Web site that became so popular with criminals that Maxus had to limit access to one stolen number per visit.

2.10 TROJAN HORSES.

Trojans are programs that pretend to be useful but that also contain harmful code or are just plain harmful.

2.10.1 1988 Flu-Shot Hoax.

One of the nastiest tricks played on the shellshocked world of early microcomputer users was the FLU-SHOT-4 incident of March 1988. With the publicity given to damage caused by destructive, self-replicating virus programs distributed through electronic bulletin board systems (BBSs), it seemed natural that public-spirited programmers would rise to the challenge and provide protective screening.

Flu-Shot-3 was a useful program for detecting viruses. Flu-Shot-4 appeared on BBSs and looked just like version 3; however, it actually destroyed critical areas of hard disks and any floppies present when the program was run. The instructions that caused the damage were not present in the program file until it was running; this self-modifying code technique makes it especially difficult to identify Trojans by simple inspection of the assembler-level code.

2.10.2 Scrambler, 12-Tricks and PC Cyborg.

Other early and notorious PC Trojans from the late 1980s that are still remembered in the industry included:

- The Scrambler (also known as the KEYBGR Trojan), which pretended to be a keyboard driver (KEYBGR.COM) but actually made a smiley face move randomly around the screen

- The 12-Tricks Trojan, which masqueraded as CORETEST.COM, a program for testing the speed of a hard disk, but actually caused 12 different kinds of damage (e.g., garbling printer output, slowing screen displays, and formatting the hard disk)

- The PC Cyborg Trojan (or “AIDS Trojan”), which claimed to be an AIDS information program but actually encrypted all directory entries, filled up the entire C disk, and simulated COMMAND.COM but produced an error message in response to nearly all commands.

2.10.3 1994: Datacomp Hardware Trojan.

On November 8, 1994, a correspondent reported to the RISKS Forum Digest that he had been victimized by a curious kind of Trojan:

I recently purchased an Apple Macintosh computer at a “computer superstore,” as separate components—the Apple CPU, and Apple monitor, and a third-party keyboard billed as coming from a company called Sicon.

This past weekend, while trying to get some text-editing work done, I had to leave the computer alone for a while. Upon returning, I found to my horror that the text “welcome datacomp” had been inserted into the text I was editing. I was certain that I hadn't typed it, and my wife verified that she hadn't, either. A quick survey showed that the “clipboard” (the repository for information being manipulated via cut/paste operations) wasn't the source of the offending text.

As usual, the initial reaction was to suspect a virus. Disinfectant, a leading anti-viral application for Macintoshes, gave the system a clean bill of health; furthermore, its descriptions of the known viruses (as of Disinfectant version 3.5, the latest release) did not mention any symptoms similar to my experiences.

I restarted the system in a fully minimal configuration, launched an editor, and waited. Sure enough, after a (rather long) wait, the text “welcome datacomp” once again appeared, all at once, on its own.

Further investigation revealed that someone had put unauthorized code in the ROM chip used in several brands of keyboard. The only solution was to replace the keyboard. Readers will understand the possible consequences of a keyboard that inserts unauthorized text into, say, source code. Winn Schwartau, the renowned computer security expert, has coined the word “chipping” to refer to such unauthorized modification of firmware.

2.10.4 Keylogger Trojans.

By the mid-2000s, software and hardware Trojans designed to capture logs of keystrokes and sometimes to transmit those logs via covert Internet connections had become a well-known tool of industrial espionage. The United States Department of Homeland Security issued a warning in December 2005 that included this overview:

According to industry security experts, the biggest security vulnerability facing computer users and networks is email with concealed Trojan Horse software—destructive programs that masquerade as benign applications and embedded links to ostensibly innocent websites that download malicious code. While firewall architecture blocks direct attacks, email provides a vulnerable route into an organization's internal network through which attackers can destroy or steal information.

Attackers try to circumvent technical blocks to the installation of malicious code by using social engineering—getting computer users to unwittingly take actions that allow the code to be installed and organization data to be compromised.

The techniques attackers use to install Trojan Horse programs through email are widely available, and include forging sender identification, using deceptive subject lines, and embedding malicious code in email attachments.

Developments in thumb-sized portable storage devices and the emergence of sophisticated keystroke logging software and devices make it easy for attackers to discover and steal massive amounts of information surreptitiously.42

2.10.5 Haephrati Trojan.

A case that made the news in the mid-2000s began when Israeli author Amon Jackont was upset to find parts of the manuscript on which he was working posted on the Internet. Then someone tried to steal money from his bank account. Suspicion fell on his stepdaughter's ex-husband, Michael Haephrati. Police discovered a keystroke logger on Jackont's computer. It turned out that Haephrati had also sold spy software to clients; the Trojan was concealed in what appeared to be confidential e-mail. Once installed on the victims' computers, the software sent surveillance data to a server in London, England.

Haephrati was detained by UK police and investigations began in Germany and Israel. Twelve people were detailed in Israel; eight others were under house arrest. Suspects included private investigators and top executives from industrial firms. Victims included Hewlett-Packard, the Ace hardware stores, and a cable-communications company.

Michael and Ruth Haephrati were extradited from Britain for trial in Israel on January 31, 2006. They were accused of installing the Trojan horse program that activated a key logger with remote-reporting capabilities.43

In March 2006, the couple were indicted in Tel Aviv for corporate espionage.44 They pleaded guilty to the charges45 and were sentenced to four and two years of jail, respectively, as well as punished with fines.46

The story did not end there, however. Two years later, “Four members of the Israeli Modi'in Ezrahi private investigation firm were sentenced on Monday after they were found guilty of using Trojan malware to steal commercially sensitive information from their clients' competitors.”47 The report continues:

Asaf Zlotovsky, a manager at the Modi'in Ezrahi detective firm, was jailed for 19 months. Two other employees, Haim Zissman and Ron Barhoum, were sent to prison for 18 and nine months respectively. The firm's former chief exec, Yitzhak Rett, the victim of an apparent accident when he fell down a stairwell during a break in police questioning back in 2005, escaped a jail sentence under a plea bargaining agreement. Rett was fined 250,000 Israeli Shekels (£36,500) and ordered to serve ten months' probation over his involvement in the scam.

However, an article in April 2008 reported that Michael Haephrati “claimed that there was no jail time, and that he was completely free. As a matter of fact he was going to continue to offer his Trojan Horse service but this time he would only work with ‘law enforcement agencies.’”48

2.10.6 Hardware Trojans and Information Warfare.

As this chapter was going to press, a flurry of news stories discussed the dangers of growing reliance on Chinese-manufactured computing components.

U.S. Defense Department sources say privately that the level of Chinese cyberattacks obliges them to avoid Chinese-origin hardware and software in all classified systems and as many unclassified systems as fiscally possible. The high threat of Chinese cyberpenetrations into U.S. defense networks will be magnified as the Pentagon increasingly loses domestic sources of “trusted and classified” microchips.49

The discovery of counterfeit Cisco routers worsened concerns about the reliability of Chinese-manufactured network equipment.50 The FBI, Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), Customs and Border Protection (CBP), and the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) worked together to track a massive pattern of counterfeit network hardware including Cisco routers; these investigations and seizures raised questions about the reliability and trustworthiness of such equipment, much of which was manufactured in the People's Republic of China. Although Cisco scientists examined some of the counterfeit equipment and found no back doors, concern was serious enough that government agencies created test chips to challenge quality assurance processes at military contractors:

In April [2008], the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, part of the Defense Department, began distributing chips with hidden Trojan horse circuitry to military contractors participating in an agency program, Trusted Integrated Circuits. The goal is to test forensic techniques for finding hidden electronic trap doors, which can be maddeningly elusive. The agency is not yet ready to announce the results of the test, said Jan Walker, a spokeswoman for the agency.51

2.11 NOTORIOUS WORMS AND VIRUSES.

The next sections briefly describe some of the outstanding incidents that are often mentioned in discussions of the history of malware.52

2.11.1 1970–1990: Early Malware Outbreaks.

The ARPANET was the precursor of the Internet.53 According to several reports:

Sometime in the early 1970s, the Creeper virus was detected on ARPANET, a US military computer network which was the forerunner of the modern Internet. Written for the then-popular Tenex operating system, this program was able to gain access independently through a modem and copy itself to the remote system. Infected systems displayed the message, “I'M THE CREEPER: CATCH ME IF YOU CAN.”

Shortly thereafter, the Reaper program was anonymously created to delete Creeper. Reaper was a virus: it spread to networked machines and if it located a Creeper virus, Reaper would delete it. Even the participants are unable to say whether Reaper was a response to Creeper, or if it was created by the same person or persons who created Creeper in order to correct their mistake.54

By 1981, the Apple II computer was a popular system among hobbyists; the Elk Cloner virus spread via infected floppy disks and is regarded as “the first large-scale computer virus outbreak in history.”55

In 1986, the Brain boot-sector virus was the first IBM-PCs malware to spread around the world. It was created by two brothers from Lahore, Pakistan, and included this text:

Welcome to the Dungeon (c) 1986 Brain & Amjads (pvt) Ltd VIRUS_SHOE RECORD V9.0 Dedicated to the dynamic memories of millions of viruses who are no longer with us today - Thanks GOODNESS!! BEWARE OF THE er…VIRUS: this program is catching program follows after these messages….$#@%$@!!

The Lehigh Virus appeared at Lehigh University in Pennsylvania in 1987 and damaged the files of several professors and students. This early program-infector targeted only command.com and was therefore extremely limited in its spread.

In 1988, the Jerusalem virus, a file infector that reproduced by inserting its code into EXE and COM files, caused a global PC epidemic.

Another noteworthy infection of 19988 came from the self-encrypting Cascade virus of 1988, which confused many naive users who interpreted the falling symbols on their screen as part of an unexpected screen saver. This virus was one of the earliest examples of the attempts to counter signature-based antivirus products.

2.11.2 December 1987: Christmas Tree Worm.

In December 1987, users of IBM mainframe computers connected to the European Academic Research Network (EARN), BITNET, and the IBM company VNET were flooded with e-mail bearing a character-based representation of a Christmas tree. A student at Technische Universität Clausthal56 in Germany launched “a worm, written in an IBM-specific language called REXX.”57 The worm used the victim's list of correspondents to send copies of itself to everyone on the list.58

2.11.3 November 2, 1988: Morris Worm.

On November 2, 1988, the Internet was rocked by the explosive appearance of unauthorized code on systems all over the world. At 17:00 EST on November 2, 1988, Robert T. Morris, a student at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York, released a worm into the Internet. By midnight, it had attacked VAX computers running 4 BSD UNIX and SUN Microsystems Sun 3 computers throughout the United States. One of the most interesting aspects of the worm's progress through the Internet was the almost complete independence of its path from normal geographical constraints. It sometimes leaped from coast to coast faster than it reached physically neighboring computer systems. The worm graphically demonstrated that cyberspace has its own geography.

The worm often superinfected its hosts, leading to slowdowns in overall processing speed. The first Internet warning (“We are under attack”) was posted at 02:38 on November 3to the TCP-IP list by a scientist at University of California at Berkeley. At 03:34, Andy Sudduth, a friend of Morris's at Harvard, posted a warning message (“There may be a virus loose on the internet”) anonymously and included a few comments on how to stop the worm. Unfortunately, Spafford writes, the Internet was so severely impeded by the worm that this message was not widely distributed for over 24 hours.

By 06:00 on the morning of November 3, messages were creeping through the Internet with details of how the worm worked. The news spread via news groups such as the TCP-IP list, Usenix 4bsd-ucb-fixes, and the Usenet news.announce.important group. Spafford and his friends and colleagues on the Internet collaborated feverishly on providing patches against the worm.

Meanwhile, as word spread of the attack, some systems administrators began cutting their networks out of the Internet. The Defense Communications Agency isolated its Milnet and Arpanet networks from each other around 11:30 on November 3. At noon, machines in the science and technology center at the Stanford Research Institute were shut down.

By late on November 4, a comprehensive set of patches was posted on the Internet to defend systems against the worm. That evening, a New York Times reporter told Spafford that the author of the worm had been found.

By November 8, the Internet seemed to be back to normal. A group of concerned computer scientists met at the National Computer Security Center to study the incident and think about preventing recurrences of such attacks. Spafford put the incident into perspective with the comment that the affected systems were no more than 5 percent of the hosts on the Internet. It would be foolish to dismiss Morris's electronic vandalism as a prank or to claim that the worm alerted managers to weak security on their systems. Nonetheless, it is true that the incident contributed to the establishment of the Computer Emergency Response Team at the Software Engineering Institute of Carnegie-Mellon University. For these blessings, however, we owe no gratitude to Robert T. Morris.

In 1990, Morris was found guilty under the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act of 1986. The maximum penalties included five years in prison, a $250,000 fine, and restitution costs. Morris was ordered to perform 400 hours of community service, sentenced to three years probation, and required to pay $10,000 in fines. He was expelled from Cornell University.

His lawyers appealed the conviction to the Supreme Court of the United States. Their arguments included lack of evil intent (he did not mean to cause harm, honest—even though his worm took extraordinary precautions to conceal itself) and they deplored the scandalous behavior of Cornell University authorities, who had the temerity to search their own electronic mail message system to locate evidence that incriminated Morris. The lawyers also argued that sending a mail message might become a crime if Morris's conviction were upheld.

The Supreme Court upheld the decision by declining to hear the appeal.59

Robert T. Morris eventually became an associate professor in the Electrical Engineering and Computer Science Department of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and a member of the Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory.60

2.11.4 Malware in the 1990s.

The most significant malware development of the 1990s was the release in July 1995 of the world's first widely distributed macro-language virus. The macro.concept virus made its appearance in MS-Word for Windows documents. It demonstrated how to use the macro programming language, common to many Microsoft products, to generate self-reproducing macros that spread from document to document. Within a few months, clearly destructive versions of this demonstration virus appeared.

Macro viruses were a dangerous new development. As explained in a recent history of viruses and antiviruses:

- Putting self-reproducing code in easily- and frequently exchanged files, such as documents, greatly increased the infectiousness of the viruses

- Virus writers shifted their attention to a much easier programming language than assembly.

- E-mail exchanges of infected documents were a far more effective mechanism for virus infection than exchanges of infected programs or disks.

- “[M]acro viruses were neither platform-specific, nor OS-specific. They were application-based.”61

In the latter half of the 1990s, macro viruses replaced boot sector viruses and file infector viruses as a major type of malicious self-reproducing malware; during that period, additional types of script-based, network worms also increased.

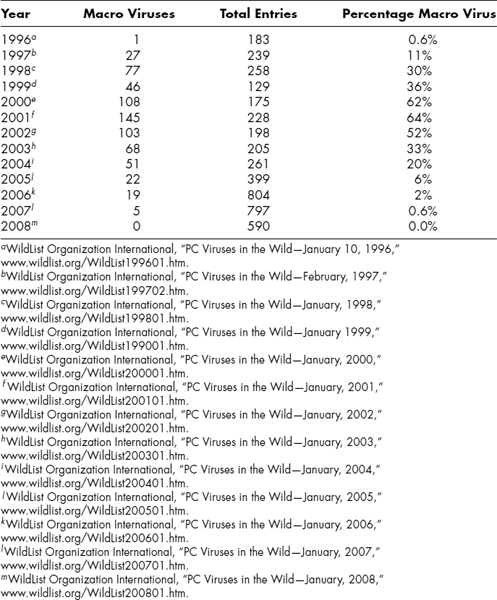

Exhibit 2.1 shows the rise and fall of prevalence of macro viruses over the decade from discovery to extinction using data from the WildList archives. The WildList shows malware identified on user systems by at least two virus researchers.62

Roger Thompson summarizes the developments in malware in the 1990s in this way:

By around 2000, macro viruses ceased to be a problem because the new version of MS-Office 2000 included features that blocked macro viruses. The next step in the evolution of malware was the mass mailers like the ILOVEYOU worm and then the network worms. These were easy to write and easy to obfuscate by varying the text contents, thus defeating signature scanners. These worms spread very quickly until the release of Windows XP Service Pack 2, which forced the Windows Firewall to be on by default. After that extinction-level event, criminals moved onward to creating mass mailers and bots which could spread malware and spam or cause distributed denial-of-service through communication via the trusted Web sites accessed through browsers that created a tunnel through the firewall.63

2.11.5 March 1999: Melissa.

On Friday, March 26, 1999, the CERT/CC received initial reports of a fast-spreading new MS-Word macro virus. “Melissa” was written to infect such documents; once loaded, it uses the victim's MAPI-standard e-mail address book to send copies of itself to the first 50 people on the list. The virus attaches an infected document to an e-mail message with subject line “Subject: Important Message From <name>” where <name> is that of the inadvertent sender. The e-mail message reads: “Here is that document you asked for…don't show anyone else;-)” and includes a MS-Word file as an infected attachment. The original infected document, “list.doc,” was a compilation of URLs for pornographic Web sites. However, as the virus spread, it was capable of sending any other infected document created by the victim.

Because of this high replication rate, the virus spread faster than any previous virus in history. On many corporate systems, the rapid rate of internal replication saturated e-mail servers with outbound automated junk e-mail. Initial estimates were in the range of 100,000 downed systems. Antivirus companies rallied immediately, and updates for all the standard products were available within hours of the first notices from CERT/CC.

The search for the originator of the Melissa e-mail computer virus/worm began immediately after the outbreak. Initial findings traced the virus to Access Orlando, a Florida Internet Service Provider (ISP), whose servers were shut down by order of the FBI for forensic examination; the systems were then confiscated. That occurrence was then traced back to Source of Kaos, a free-speech Web site where the virus may have lain dormant for months in a closed but not deleted virus-distributor's pages. Investigators discovered a serial number in the vector document, written with MS-Word; the undocumented serial number helped law enforcement when investigators circulated it on the Net to help track down the perpetrator.

EXHIBIT 2.1 Rise and Fall in Macro Viruses in the WildList, 1996–2008

The next steps turned to the value-added network AOL, where the virus was released to the public. The giant ISP's information helped to identify a possible suspect and by April 2, the FBI arrested David L. Smith (age 30) of Aberdeen, New Jersey. Smith apparently panicked when he heard the FBI was on the trail of the Melissa spawner and he threw away his computer—stupidly, into the trash at his own apartment building.

Smith was charged with second-degree offenses of interruption of public communication, conspiracy to commit the offense and attempt to commit the offense, third-degree theft of computer service, and third-degree damage or wrongful access to computer systems. If convicted, Smith faced a maximum penalty of $480,000 in fines and 40 years in prison. On December 10, 1999, Smith pleaded guilty to all federal charges and agreed to every particular of the indictment, including the estimates by the International Computer Security Association of at least $80 million of consequential damages due to the Melissa infections.64

2.11.6 May 2000: I Love You.

Starting around May 4, 2000, e-mail users opened messages from familiar correspondents with the subject line “I love you”; many then opened the attachment, LOVE-LETTER-FOR-YOU.txt.vbs, which infected the user's e-mail address book and initiated mass mailing of itself to all the contacts. The “Love Bug” was the fastest-spreading worm to that time, infecting computers all over the world, starting in Asia, then Europe.65

On May 11, Filipino computer science student Onel de Guzman of AMA Computer College in Manila admitted to authorities that he may “accidentally have launched the destructive Love Bug virus out of youthful exuberance.” He did not admit that he had created the malware himself; however, the name GRAMMERSoft appeared in the computer code of the virus, and that was the name of a computer group to which the 23-year-old de Guzman belonged.66

In September 2000, de Guzman participated in a live chat hosted by CNN.com; he vigorously defended virus-writing and blamed the creators of vulnerable systems for releasing poorly designed software. He refused to take responsibility for writing the worm.67

Philippine authorities tried to prosecute de Guzman but had to drop their attempts in August 2000 for lack of sufficient evidence. Due to the lack of computer crime laws at the time, it was impossible for other countries such as the United States to extradite the suspect: International principles of dual criminality require equivalent laws in both jurisdictions before extradition can proceed.

By October 2000, de Guzman had refused to take responsibility for writing the worm and publicly stated, “‘I admit I create viruses, but I don't know if it's one of mine…. If the source code was given to me, I could look at it and see. Maybe it is somebody else's, or maybe it was stolen from me.”68

The “I Love You” case was a wake-up call for the international community to think about standardizing computer crime laws around the globe.69

2.12 SPAM.

Chapter 20 in this Handbook includes a detailed history of unsolicited commercial e-mail and the reason it is called spam. This section looks solely at a seminal abuse of the USENET in 1994 and trends in spam over the next decade.

2.12.1 1994: Green Card Lottery Spam.

On April 2, 1994, Laurence A. Canter and Martha S. Siegel posted an advertisement for legal services connected to the U.S. government's Green Card Lottery to over 6,000 USENET groups. Instead of cross-posting their commercial message, they used a script to post a copy of the message separately to every group. The former method would have shown the message to USENET users once; Canter and Siegel's abuse of the USENET made their ad show up in every affected group to which users subscribed.70

Reaction worldwide was massive. Automated cancelbots trolled the USENET deleting the unwanted messages; the attorneys' ISP was so overloaded with e-mail complaints that its servers crashed. Canter and Siegel were reviled in postings and newspaper articles.71 Their unsavory backgrounds were posted in discussion groups, including details of disciplinary hearings before the Florida Bar and accusations of dishonesty and unprofessional behavior.72

Unfazed, the couple published a book about how to abuse the Internet using spam and defended their actions in interviews as an expression of freedom of speech; they dismissed critics as “wild-eyed zealots” or as commercial interests intent on controlling the Internet for their own gain.73

Canter was eventually disbarred in Tennessee, in part for his spamming.74 He remained unrepentant; in 2002, he spammed 50,000 K–12 teachers with an advertisement for a book whose title he liked so he could harvest payments for referrals from Amazon.75

2.12.2 Spam Goes Global.

Over the next decade, the incidence of spam grew explosively. By 2007, spam watchers and anti-spam companies reported that around 88 percent of all e-mail traffic on the Internet was spam. Spammers caused so much irritation that companies developed software and hardware solutions for filtering e-mail by content. Spammers responded by increasing the number of images in their spam, making content filtering more difficult. At one point, the amount of spam grew 17 percent between one day and the next as spammers began pumping PDF files into spam pipelines.76

Botnets spawned through infected zombie machines established rogue SMTP nodes using innocent (and ignorant) PC users' computers and persistent high-speed Internet connections.77 Spam currently provides a major vector for fraud by deceit, including in particular 4-1-9 advance fee fraud and phishing attacks.78 Advance-fee fraud usually consists of enticements to participate in the theft of ill-gotten gains such as bank deposits belonging to dead people or stolen from poor countries; the dupes who agree to participate in such illegality are promised millions of dollars—only to be told that they suddenly have to send cash for unexpected bribes or fees. If they do so, they are asked for more…and more…and more. Phishing involves sending e-mail messages that are supposed to look like official, usually alarming, warnings from banks and other institutions; victims click on links that look like one thing but actually go to the criminals' Web sites. There the victims cheerfully type in their user identification, passwords, bank account numbers, and all manner of other confidential information useful for identity theft.79 Advance-fee fraud and phishing are discussed in Chapter 20 in this Handbook.

2.13 DENIAL OF SERVICE.

Denial of service results from exhaustion or destruction of necessary resources and is thoroughly discussed in Chapter 18. However, a couple of denial-of-service attackers stand out among all the others in the last decade or so: the Unamailer and Mafiaboy.

2.13.1 1996: Unamailer.

In August 1996, someone using the pseudonym “johnny [x]chaotic” claimed the blame for a massive mail-bombing run based on fraudulently subscribing dozens of victims to hundreds of mailing lists. The denial of service was the result in part of the naïveté of list managers who accepted subscriptions for any e-mail address from any other e-mail address. In a rambling and incoherent letter posted on the Net, (s)he made rude remarks about famous and not-so-famous people, whose capacity to receive meaningful e-mail was then obliterated by up to thousands of unwanted messages a day.80 “The first attack, in August, targeted more than 40 individuals, including Bill Clinton and Newt Gingrich and brought a torrent of complaints from the people who found their names sent as subscribers to some 3,000 E-mail lists.”81

Someone claiming to be the same “Unamailer” (as the news media labeled him or her in reference to the Unabomber) launched a similar mass-subscription mail-bombing run in late December.

This attack is estimated to involve 10,139 listservs groups, 3 times greater than the one that took place in the summer, also at xchaotic's instigation. If each mailing list in this attack sent the targeted individuals just a modest 10 letters to the subscribers' computers those individuals would receive more than 100,000 messages. If each listing system sent 100 messages—and many do—then the total messages could tally 1,000,000.82

In December, the attacker(s) sneered at list administrators for failing to use authentication before allowing subscriptions and wrote that they would continue their attacks until practices changed.83

Partly as a result of the Unamailer's depredations, list administrators did in fact change their practices—not that anyone thanked Johnny [x]chaotic for his method of persuasion.

2.13.2 2000: MafiaBoy.

On February 8, 2000, Yahoo.com suffered a three-hour flood from a distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attack and lost its capacity to serve Web pages to visitors. The next day, the same technique was extended to Amazon.com, eBay.com, Buy.com, and CNN.com.84 Later information also showed that Charles Schwab, the online stock brokerage, had been seriously impeded in serving its customers because of the DDoS. Buy.com managers were particularly disturbed because the attack occurred on the day of their initial public offering. As a result of the attacks, a number of firms formed a consortium to fight DDoS attacks.85

Investigation by the RCMP and the FBI located a 15-year-old child in west-end Montreal who used a modem to control zombies in his DDoS escapade:

On April 15, 2000, the RCMP arrested a Canadian juvenile known as Mafiaboy for the February 8th DDoS attack on CNN in Atlanta, Georgia. On August 3, 2000, Mafiaboy was charged with 64 additional counts. On January 18, 2001, Mafiaboy appeared before the Montreal Youth Court in Canada and pleaded guilty to 56 counts. These counts included mischief to property in excess of $5,000 against Internet sites, including CNN.com, in relation to the February 2000 attacks. The other counts related to unauthorized access to several other Internet sites, including those of several US universities. On September 12, 2001, Mafiaboy appeared before the Montreal Youth Court in Canada and was sentenced to eight months “open custody,” one year probation, and restricted use of the Internet.86

MafiaBoy's name was not released by Canadian authorities because of Canadian laws protecting juveniles, although several U.S. reporters distributed his identity in their publications. His chief contribution to the history of computer crime was to demonstrate asymmetric warfare in cyberspace.87 His actions showed that even an ignorant child with little knowledge of computing could use low-tech hardware and tools available to anyone on the Internet to cripple major organizations.

2.14 HACKER UNDERGROUND OF THE 1980S AND 1990S.

Newcomers to the field of information assurance will encounter references to the computer underground in texts, articles, and discussions. The sections that follow provide thumbnail sketches of some of the key groups and events in the shadowy world of criminal hacking, (known as black hats, in contrast to white hats, who are law enforcement and establishment security experts) and the intermediate range of well-intentioned rebels who use unorthodox means to challenge corporations and governments over what they see as security failings (these people are often called gray hats).

2.14.1 1981: Chaos Computer Club.

On September 12, 1981, a group of German computer enthusiasts with a strong radical political orientation formed the Chaos Computer Club (CCC) in Hamburg.88 One of their first achievements was to demonstrate a serious problem in the Bundespost's (German post office) new Bilschirmtext (BTX) interactive videotext service in 1984, not long after the service was announced.89 The CCC used security flaws in BTX to transfer a sizable amount of money into their own bank account through a script that ran overnight as a demonstration to the press (returning the money publicly).

After the Legion of Underground (LoU) announced on January 1, 1999, that they would attack and disable the computer systems of the People's Republic of China and of Iraq, a coalition of hacker organizations including the CCC announced opposition to the move. “We strongly oppose any attempt to use the power of hacking to threaten or destroy the information infrastructure of a country, for any reason,” the coalition said. “Declaring war against a country is the most irresponsible thing a hacker group could do. This has nothing to do with hacktivism or hacker ethics and is nothing a hacker could be proud of,” the coalition said in the statement.

The CCC has, in general, challenged the general view that “hacker” necessarily means “criminal hacker.”90 Their annual Chaos Communications Conferences have proven to be a site of technology exchange and serious discussion of information security issues. Their continued commitment to the rule of law (except where their own activities are concerned), and their willingness to engage authorities in the courts when necessary has gained them an unusual degree of credibility and acceptance in the information security community as relatively pale-gray hats.91

2.14.2 1982: The 414s.

One morning in June 1982, a system administrator for a DEC VAX 11/780 minicomputer at the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center in Manhattan found his system down. Investigation led to the discovery that his and dozens of other systems around the country were being hacked by Milwaukee-area teenagers and others aged 15 to 22. The youths called themselves the 414s after the Milwaukee area code.

Using home computers connected to ordinary telephone lines, they had been breaking into computers across the U.S. and Canada, including one at a bank in Los Angeles, another at a cement company in Montreal and, ominously, an unclassified computer at a nuclear weapons laboratory in Los Alamos, [New Mexico].92

In March 1984, “two members of Milwaukee's 414 Gang…pleaded guilty to mis-demeanor charges of making obscene or harassing phone calls. Maximum sentence for each charge: six months in jail and a $500 fine.”93

2.14.3 1984: Cult of the Dead Cow.

Another influential criminal-hacker group is the Cult of the Dead Cow (cDc), which used to sport amusing (although intentionally offensive to some) cartoons such as that of a crucified cow.94 The cDc was noted for its consistent use of humor and parody; for example, “Swamp Rat's” 1985 article on building “The infamous…GERBIL FEED BOMB” included instructions such as “Light the fuse if you put one in. If you dropped a match into it, then go to the nearest phone, dial ‘911’ and tell the nice people that you have a large number of glass shards embedded in your lower body. An ambulance should be there soon.”95

The cDc became important proponents of hactivism in the 1990s—the use of criminal hacking techniques for political purposes. They also released a number of hacking tools, of which Back Orifice (BO) and especially Back Orifice 2000 (BO2K) were notorious examples. BO2K was ostensibly a remote administration tool but was in fact a Trojan that ran in stealth mode and allowed remote control of infected machines.96 Some observers felt that presenting BO2K as a legitimate tool was another instance of cDc's satirical bent: The idea that anyone would consider software written by criminal hackers as a trustworthy administration tool struck them as ludicrous.

2.14.4 1984: 2600: The Hacker Quarterly.

Eric Corley founded 2600: The Hacker Quarterly in 1984. This publication has become a standard-bearer for proponents of criminal hacking. The magazine has published a steady stream of explanations of how to exploit specific vulnerabilities in a wide range of operating systems and application environments. In addition, the editor's political philosophy has influenced more than one generation of black-hat and gray-hat hackers:

In the worldview of 2600, the tiny band of technocrat brothers (rarely, sisters) are a besieged vanguard of the truly free and honest. The rest of the world is a maelstrom of corporate crime and high-level governmental corruption, occasionally tempered with well-meaning ignorance. To read a few issues in a row is to enter a nightmare akin to Solzhenitsyn's, somewhat tempered by the fact that 2600 is often extremely funny.97

2.14.5 1984: Legion of Doom.

The DC Comics empire created an animated cartoon series called Super Friends that appeared in 1973; it starred various DC Comics heroes, such as Superman, Aquaman, Wonder Woman, and Batman.98 In a follow-up series called Challenge of the Super Friends that ran from 1978 through 1979, the archenemies of these heroes were a group known as the Legion of Doom, which included Lex Luthor, archenemy of Superman.99 A group of phone phreakers who later turned to criminal hacking called themselves the Legion of Doom (LOD); their founder called himself “Lex Luthor.” Another major member was Loyd Blankenship (“The Mentor”).

Bruce Sterling describes the LOD as an influential hacker underground group of the 1980s and one of the earliest to capitalize on regular publication of their findings of vulnerabilities and exploits in the phone system and then in computer networks:

LOD members seemed to have an instinctive understanding that the way to real power in the underground lay through covert publicity. LOD were flagrant. Not only was it one of the earliest groups, but the members took pains to widely distribute their illicit knowledge. Some LOD members, like “The Mentor,” were close to evangelical about it. Legion of Doom Technical Journal began to show up on boards throughout the underground.

LOD Technical Journal was named in cruel parody of the ancient and honored AT&T Technical Journal. The material in these two publications was quite similar—much of it, adopted from public journals and discussions in the telco community. And yet, the predatory attitude of LOD made even its most innocuous data seem deeply sinister; an outrage; a clear and present danger.100

In the later 1980s, the LOD actually helped law enforcement on occasion by re-straining malicious hackers.

One of the best-known members was Chris Goggans, whose handle was “Erik Bloodaxe”; he was also an editor of Phrack and later became part of the Masters of Deception (MOD), which was involved in a conflict with LOD in 1990 and 1991 known in hacker circles as “The Great Hacker War.”101

Another well-known hacker who started in LOD and moved to MOD was Mark Abene (“Phiber Optik”), who was eventually imprisoned for a year after pleading guilty in federal court to conspiracy and unauthorized access to federal-interest computers (a violation of 18 USC 1030(a), the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act of 1986).102 Abene's punishment was the subject of much protest in the hacker community and elsewhere.103

2.14.6 1985: Phrack.

Phrack began publishing in November 1985. With a new issue every month or two at first, the electronic magazine continued uninterrupted distribution of technical information and rants. The uncensored commentary provided a fascinating glimpse of some of the personalities and worldviews of its contributors and editors, including Taran King and Craig Neidorf (later to become famous as “Knight Lightning” and for his involvement in an abortive prosecution involving Bell-South documents). For example, Phrack published what became known as the “Hacker Manifesto”—held up by criminal hackers as a light unto the nations (“Written almost 15 years ago by The Mentor, this should be taped up next to everyone's monitor to remind them who we are, this rang true with Hackers, but it now rings truth to the internet generation.”104 ) but viewed with skepticism by security professionals. It read in part:

This is our world now…the world of the electron and the switch, the beauty of the baud. We make use of a service already existing without paying for what could be dirt-cheap if it wasn't run by profiteering gluttons, and you call us criminals. We explore…and you call us criminals. We seek after knowledge…and you call us criminals. We exist without skin color, without nationality, without religious bias…and you call us criminals. You build atomic bombs, you wage wars, you murder, cheat, and lie to us and try to make us believe it's for our own good, yet we're the criminals.

Yes, I am a criminal. My crime is that of curiosity. My crime is that of judging people by what they say and think, not what they look like. My crime is that of outsmarting you, something that you will never forgive me for.

I am a hacker, and this is my manifesto. You may stop this individual, but you can't stop us all…after all, we're all alike.105