CHAPTER 74

PROFESSIONAL CERTIFICATION AND TRAINING IN INFORMATION ASSURANCE

Christopher Christian, M. E. Kabay, Kevin Henry, and Sondra Schneider

74.1 BUILDING SKILLS THROUGH PROFESSIONAL EDUCATION

74.1.2 Certificates, Certification, and Accreditation

74.1.3 ANSI/ISO/IEC 17024 Accreditation of Personnel Certification

74.1.6 Summary of Accreditation, Certification, and Certificates

74.2 INFORMATION SECURITY CERTIFICATIONS

74.2.1 Certified Internal Auditor (CIA)

74.2.2 Certified Information Systems Auditor (CISA)

74.2.3 Certified Information Security Manager (CISM)

74.2.4 Certified Information Systems Security Professionals (CISSP)

74.2.5 Systems Security Certified Practitioner (SSCP)

74.2.6 Global Information Assurance Certification

74.3 PREPARING FOR SECURITY CERTIFICATION EXAMINATIONS

74.3.4 Books and Free Review Materials

74.4 COMMERCIAL TRAINING IN INFORMATION ASSURANCE

74.4.1 Security University Classes and Certifications

74.4.2 Getronics Security University

74.1 BUILDING SKILLS THROUGH PROFESSIONAL EDUCATION.

Perhaps one of the most critical decisions an organization has to make today is how to invest in its staff. Technology, policies, and well-defined processes are all important elements of an organization's infrastructure, but the most valuable and versatile asset that any company has today is its personnel.

How do we recruit, develop, and maintain a skilled and professional staff, with other organizations competing for our trained experts, and how do we maintain their level of proficiency despite the rapid changes in technology and the many pressures of keeping the business operating?

Many companies struggle with the need to provide opportunity for their staff, while realizing that training and educating their staff makes these people attractive to other organizations.

Government regulations and legislation as well as increasing expectations from customers, suppliers, and business partners require information technology (IT) staff who are up to date with the latest technologies and who can provide assurance of reliable and stable IT operations. In most cases, a company is required either to develop internal resources to meet these demands or to pay a large price to recruit such people from external sources. More and more organizations are building relationships with universities and technical colleges to ensure that a ready supply of new graduates is available for their use. However, to retain good employees, it is necessary to make expensive investments in their further education. This is money and time that is hard to justify in some cases, and there are numerous options when it comes to registering for a professional training or educational program.

74.1.1 Training and Education.

There is a significant difference between training and education. In this chapter, the emphasis is on training; in Chapter 75 of this Handbook, it is on education. When a company invests in a technology such as a firewall or intrusion prevention system, it often has to provide training to the people responsible for managing the device. Such training is best provided through official sources because the product vendors can often arrange for training as a part of the purchase price, and there is a certain assurance that the training materials are up to date if they are provided by an official source.

One common mistake that companies make is to send only one person to the official training program and then trust that person to pass the knowledge gained to their peers. What usually happens is that the person who attends the course provides a 10-minute overview to the rest of the staff when she returns. In part, this kind of slipshod knowledge transfer occurs because many organizations have no systematic way of evaluating a training program and ensuring that they receive value for their investment, and they put no thought into knowledge sharing.

All worthwhile education and training programs should go beyond merely passing on information passively; they should provide the students with some form of practical work—whether through labs, a case study, or the need to prepare for and pass a difficult project or an extensive examination. It is too easy to have programs that are not really effective—the students can easily slip into a state of “lecture hypnosis” where they are following along with the program but not really absorbing or digesting the material. It is only when they are asked to answer questions about the material, or use it in a practical manner, that most people will truly grasp and retain the information.

One factor to consider is the location of the class. Far too many students do not gain the expected benefit from a class due to its location. Ideally, a student should not be continuously distracted or pulled from the program to address issues back at the office or to handle e-mail during the class. Although it is possible to multitask, distraction makes what is being said in the class difficult to absorb. Lack of concentration causes the sponsoring organization to lose the investment it made in the class; students may ask questions that were addressed earlier and thus frustrate other students; and distracted students may do poorly in the lab work or examinations and cause conflict by blaming the course or the instructor. While a student is assigned to a training class, he should not participate in activities back at the office except in an emergency. As for holding classes in a resort or holiday location, the distractions may make it even harder for the students to focus on the course—especially if they are busy late into the evenings. Training should be held at facilities that enable serious study and learning. The courses themselves should not be just interesting hot topics but rather those that will directly benefit employees in their work–and as soon as possible. Avoid educating someone in skills they will not use for several months: since they will probably have forgotten most of the information by the time they try to use it.

Education and training are sometimes seen as a reward for an employee or a measure of respect for the staff. Although reward and respect are important, it is inappropriate to hand out training assignments as if they were perquisites of rank or signs of management favor. Courses should be focused on meeting specific objectives. In addition, to emphasize that learning is legitimate work and not a perk, employees who take assigned courses on weekends or outside their normal work shifts should be assigned compensatory time to make up for the use of their personal time.

74.1.2 Certificates, Certification, and Accreditation.

Sometimes students, professionals, and marketers use the terms “certificate” and “certification” interchangeably. In addition, academics and professionals sometimes differ in their interpretation of “accreditation.”

- A certificate is a “document providing official evidence: an official document that gives proof and details of something such as personal status, educational achievements, ownership, or authenticity.”1

- Certification, in this context, is the process (thus, a verb) of examining the work experience, knowledge and trustworthiness of a candidate for a particular certificate; confusingly, the certificate granted for qualified applicants is often referred to as a particular certification (and thus, a noun).

- “Accreditation” refers to the process of “officially recogniz[ing]” a person or organization as having met a standard or criterion. In information assurance, accreditation is carried out by official, industry- and government-recognized bodies.

The next sections explain the three of the most important accreditation organizations and processes for information assurance: ANSI/ISO/IEC 17024, NOCA/NCCA, and IACE.

74.1.3 ANSI/ISO/IEC 17024 Accreditation of Personnel Certification.

The International Organization of Standardization (ISO) and the International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) have developed a global, voluntary benchmark for organizations responsible for certification of personnel. Fully enacted as of April 1, 2003, this international standard (ANSI/ISO/IEC 17024) was designed to harmonize the personnel certification process worldwide and create more cost-effective global standards for certifying workers in a wide range of fields.

This accreditation process involves both a review of a paper application and the performance of an audit (on-site visit) to validate information provided by each applicant organization. The use of an on-site audit for accreditation of personnel-certification agencies is unique to ANSI. More than 300,000 professionals held certifications from organizations accredited under ANSI's ANSI/ISO/IEC 17024 Accreditation Program at the time of writing (July 2008).

74.1.4 NOCA/NCCA.

The National Organization for Competency Assurance (NOCA), founded in 1977, promotes excellence in credentialing worldwide through these services:

- Education

- Research

- Advocacy

- Standards

- Accreditation2

The organization provides annual conferences, webinars, and publications. In 1987, NOCA created the National Commission for Certifying Agencies (NCCA) to formalize the process of accreditation of certification programs and organizations.

NCCA uses a peer review process to:

- Establish accreditation standards

- Evaluate compliance with the standards

- Recognize organizations/programs that demonstrate compliance

- Serve as a resource on quality certification

Certification organizations that submit their programs for accreditation are evaluated based on the process and products, not the content, and are therefore applicable to all professions and industries.

NCCA-accredited programs certify individuals in a wide range of professions and occupations including nurses, automotive professionals, respiratory therapists, counselors, emergency technicians, crane operators, and more. As of July 2008, NCCA has accredited over 190 programs representing 78 organizations.3

74.1.5 IACE.

The Information Assurance Courseware Evaluation (IACE) Program of the National Security Agency (NSA) provides consistency in training and education for the information assurance skills that are critical to the security of the United States. Focused on meeting the needs of U.S. Government requirements for specific levels of competence in IA, the IACE process ensures that certified institutions meet the minimum national training and education standards for the duties and responsibilities of:

- Information Systems Security (INFOSEC) Professionals, NSTISSI4011

- Senior Systems Managers, CNSSI4012

- System Administrators (SA), CNSSI 4013

- Information Systems Security Officers, CNSSI 4014

- System Certifiers, NSTISSI 4015

- Risk Analyst, CNSSI 40164

The certification process involves detailed mapping of curricula to these standards and is a prerequisite for application for certification as a Center of Academic Excellence in Information Assurance Education (CAEIAE), which is limited to colleges and universities.5

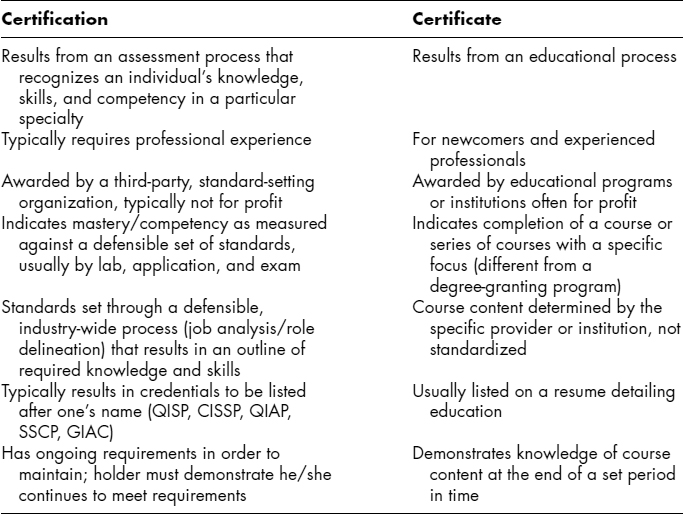

EXHIBIT 74.1 Comparison of Certification and Certificates

Institutions must apply for recertification every five years after their IACE certification.

74.1.6 Summary of Accreditation, Certification, and Certificates.

Certification differs from a certificate program, which is usually an educational offering that confers a document at the program's conclusion.

Accreditation of a certification involves a voluntary, self-regulatory process established by defined organizations and using published standards. Accreditation is granted when stated quality criteria are met.

By submitting to accreditation and enforcing documented, verified standards for professional certification, organizations such as (ISC)2, SANS, CompTIA, and Security University seek to protect the public and consumers against meaningless claims of professionalism. ANSI has evaluated and accredited (ISC)2's CISSP, CompTIA's Security +, and SANS' GIAC certifications; Security University's Q/ISP, Q/IAP, Q/WAD and Q/SSE's certifications were awaiting NOCA and ANSI approval at the time of writing (July 2008). See Exhibit 74.1 for a comparison of certification and certificates.

74.2 INFORMATION SECURITY CERTIFICATIONS.

Information systems security (ISS) has grown into one of the most important and sought after fields in the job market today. This is not a market saturated with professionals. Security professionals are well paid right out of college. This means that there is still a large demand for ISS practitioners.

Persons responsible for a company's information security are given a lot of power. With this in mind, a company should hire only those whom it can trust to do the job right, and who are ethical. Certifications provided by security groups and societies support management's quest for trustworthy, competent employees. Through rigorous examinations, adherence to approved protocols and standards of ethics, a security professional can achieve one or many professional security-related certifications.

What follows are brief summaries of some of the key security-related certifications. They are similar to each other in the way that they are obtained, and many ask that a candidate follow a strict code of ethics. The differences lie in the areas of focus of each certification. Some may be for more managerial roles, while others may cater to security architects. In the end, these certifications all try to communicate to potential employers that the certified professionals are trustworthy and that they stand out from the larger mass of uncertified candidates.

In the 2007 SC Magazine/EC-Council Salary Survey, a key finding was that “[w]hile not a mainstream occurrence, many companies are striving to ensure they're viewed as being proactive about securing digital assets by asking that new hires have a certification.”6 Indeed, there has been a steady increase in the acceptance of certification as a credible indicator of professional competence in the information assurance field. For example, even by 2003, the information technology industry had recognized the value of the Certified Information Systems Professional (CISSP)® designation. A writer for the prestigious SC Magazine wrote:

The CISSP designation from the International Systems Security Certification Consortium—or (ISC)2—is often referred to as the de facto standard when it comes to information security certifications. It is described as the “International Gold Standard,” according to (ISC)2. But companies and government agencies also place importance on more technical certifications, such as the SANS Institute's Global Information Assurance Certification (GIAC).7

In June 2004, the CISSP designation was accredited by the International Standards Organization under the ISO/IEC 1702 standard, making it a globally recognized security-professional certification.8

In August 2004, the United States Department of Defense issued DoD Directive 8570.1. The DoD Fact Sheet from (ISC)2 is provided in full as an appendix to this proposal.9 The key points of this development are:

- “…requires any full- or part-time military service member, contractor, or foreign employee with privileged access to a DoD information system, regardless of job or occupational series, to obtain a commercial information security credential accredited by ANSI or equivalent authorized body under the ANSI/ISO/IEC 17024 Standard….”

- The CISSP designation was recognized at the highest levels of both the technical and management categories.

The Fact Sheet continues with a discussion of “the significance of this mandate and of commercial certification in general.” The authors write:

This mandate will have far-reaching implications, including:

- The Directive is viewed as a government endorsement of the effectiveness and cost-efficiency of commercial certification.

- It provides military and civilian personnel with a certification that is professional, internationally recognized and vendor-neutral (not tied to any agency, technology or product).

- It provides a portable certification that is recognized in both the public and private sectors.

- It mandates and endorses a global standard (ANSI/ISO/IEC 17024).

- It positions the information security profession as a distinct job series.

In a 2008 survey sponsored by (ISC)2, analysts found that “[t]he clear differentiator in terms of career advancement and professional growth lies in certifications such as the CISSP. ‘Certifications are a measure of experience and knowledge, and businesses increasingly like to see that certification….’”10

The next sections review key certifications:

- CIA: Certified Internal Auditor

- CISA: Certified Information Systems Auditor

- CISM: Certified Information Security Manager

- CISSP: Certified Information Systems Security Professional

- GIAC: Global Information Assurance Certification

74.2.1 Certified Internal Auditor (CIA).

The Certified Internal Auditor (CIA®) is the standard certification among professionals working in the auditing field. A CIA certification recognizes that the individual has achieved a level of standards that enforces “competency and professionalism”11

This certification and three other certifications within the auditing field—Certification in Control Self-Assessment (CCSA), Certified Government Auditing Professional (CGAP), and Certified Financial Services Auditor (CFSA)—are offered through the Institute of Internal Auditors (IIA), which is globally recognized as a leader, authority, and principal educator for auditing professionals. The Institute of Internal Auditors was founded in 1941 in Altamonte Springs, Florida, and is made up of over 108,000 members found worldwide. The IIA has set the standard for all professionals by giving them the opportunities to get certified, continue their education and research, provide technological guidance, and enhance their reputation as professionals.12

The criteria for eligibility to take the CIA exam are described next.

74.2.1.1 Education.

Candidates require a suitable background in education. The candidate must have a bachelor's degree (or its equivalent) from an accredited college-level institution. No specific degree is mentioned. Experience within the workforce is not accepted by the IIA as a proper substitute in place of a degree. The only exception for those without degrees is for student candidates within their senior year in an undergraduate program or in a graduate program. If a candidate is using this substitution, it is required that she be a full-time student (12 credit hours—undergraduate or 9 credit hours—graduate). Once this is approved, the student candidate is then eligible to register and take the CIA exam. Once the students have taken the exam and passed, their certification will be withheld until they have achieved their diplomas.13

74.2.1.2 Character Reference.

Each candidate is expected to uphold and represent high standards, proper moral conviction, and show a good professional attitude. A character-reference form must be submitted by the candidate to recognize the fact that she has met all criteria to become a certified CIA and that she meets the standards applied by the code of ethics established by the IIA.14 The form must be completed by one of the following: a certified CIA, a supervisor, a manager, or an educator.

74.2.1.3 Professional Experience.

Another prerequisite to becoming a CIA candidate is having professional experience. The minimum is 24 months of internal auditing or its equivalent. By definition of “equivalent,” the other form of work that can be done is two years of work within the disciplines of auditing (internal/external), quality assurance, compliance, and internal control. However, a candidate can substitute the for one year's credit toward the required experience:

- A master's degree

- Work experience in a related professional discipline (accounting, law, or finance)

The candidate is allowed to take the CIA qualification before completing the professional experience requirements. However, the certification will be withheld until such a time as the required work hours are completed.15

74.2.1.4 Code of Ethics.

All CIAs and CIA candidates must adhere to the IIA written and approved code of ethics. “This code is a standard for all professionals within the auditing field or related working fields.”16 It is of the utmost importance that the code be followed. The introduction of the code of ethics states: “The purpose of The Institute's code of ethics is to promote an ethical culture in the profession of internal auditing.”17 It also defines four disciplines of ethical behavior: integrity, objectivity, confidentiality, and competency.18

74.2.1.5 Continuing Professional Education.

Once a person is certified as a CIA, her requirements are never completed. A CIA is defined as a person who maintains an ever-growing knowledge and skills base. It also means that CIAs are up to date on all new improvements and developments within their fields of work, relating to internal auditing standards, procedures, and techniques. To make sure that this is being done, all CIAs must send out a report listing 80 hours of continuing professional education (CPE) every two years. The report is analyzed at the IIA headquarters in Altamonte Springs, Florida.

74.2.1.6 The Exam.

The examination for a CIA consists of four parts:19

- The Internal Audit Activity's Role in Governance, Risk, and Control

- Conducting the Internal Audit Engagement

- Business Analysis and Information Technology

- Business Management Skills

Each part consists of 100 multiple-choice questions with an allowance of 2 hours 45 minutes each. The overall exam focuses on the candidate's knowledge of current auditing practices, understanding of internal audit issues, risks, and remedies. A candidate can take each exam at any time in any order.

In addition, candidates may take IIA specialty exams:

- Certification in Control Self-Assessment (CCSA)

- Certified Government Auditing Professional (CGAP)

- Certified Financial Services Auditor (CFS)20

All these exams are offered throughout the world under the auspices of local chapters of the Institute of Internal Auditors. The standard fees for the United States are listed in the current CIA Candidate Handbook.21

74.2.2 Certified Information Systems Auditor (CISA).

Sponsored by the Information Systems Audit and Control Association (ISACA®), the Certified Information Systems Auditor (CISA) is considered a serious primary certification “for all information systems (IS) audit, control, and security professionals.”22 The CISA certification Web site boasts that “the mark of excellence for a professional certification program is the value and recognition it bestows on the individual who achieves it.”23 Having a CISA opens many doors and opportunities for professionals working in the information systems discipline. The CISA is a recognized certification within all industries worldwide, and it is highly recommended that professionals in the IS field become certified with this designation. More than 40,000 people are currently recognized as certified CISAs.

The next requirements are standard for becoming a CISA.

74.2.2.1 Successful Completion of the CISA Examination.

The exam is open to anyone willing to take the test. Those who wish to embark on this path need to show an interest in information security, audit, and control. This examination is offered twice a year in June and December. The CISA Certifications Board administers the test and grades it. They then give the candidate information, upon success, about the remaining requirements to becoming a CISA. The board ensures that each exam is up to date. Each question and area is reviewed by a panel of CISA officials. The exam contains 200 multiple-choice questions to be answered, and can be taken in any number of languages. A number of CISA study guides are available through the ISACA® CISA Web site. Once the exam is successfully completed, the next steps need to be taken to become fully certified.

74.2.2.2 Experience as an Information Systems Auditor.

A minimum of five years of professional information systems auditing, control, or security work experience are needed for certification; certain equivalencies are available:

- A maximum of one year of information systems experience or one year of financial or operational auditing experience can be substituted for one year of information systems auditing, control or security experience.

- 60 to 120 completed college semester credit hours (the equivalent of an associate or bachelor degree) can be substituted for one or two years, respectively, of information systems auditing, control, or security experience.

- Two years as a full-time university instructor in a related field (e.g., computer science, accounting, information systems auditing) can be substituted for one year of information systems auditing, control, or security experience

These substitutions must be completed within 10 years of applying for the CISA application or within 5 years of taking the exam.

74.2.2.3 Code of Professional Ethics.24

All CISA members and candidates must submit to the standards applied by the code of professional ethics. This code was written and approved by the ISACA®. It is a small document with seven tenets. It can be viewed at the corresponding link in the index, or a copy can be viewed in the appendix at the end of this chapter.

74.2.2.4 Continuing Professional Education (CPE) Policy.

Member maintenance fees and a minimum of 20 hours of CPE are annually required. Over a three-year period, a total of 120 hours of CPE is required. By request, the ISACA will provide information and criteria for each member's personal CPE. The complete CPE policy can be seen on the ISACA Web site.25 It contains these sections:

- Audits of Continuing Professional Education Hours

- Revocation, Reconsideration and Appeal

- Retired and Non-practicing CISA Status

- Calculating Continuing Professional Education Hours, Certification Requirements

- Verification of Attendance Form

- Code of Professional Ethics

- Qualifying Educational Activities

74.2.2.5 Information Systems Auditing Standards.

All CISA members and candidates must adhere to the information systems auditing standards also adopted by the ISACA.26

Once the exam has been taken and successfully passed, CISA candidates must fill out an Application for Certification detailing that they met the requirements for full certification.27 This must be done within five years of passing the exam. Annual membership fees are part of the requirement. The continuing professional education policy must be followed to assure that all CISA members are up to date with all auditing practices and policies within the fields of information systems auditing, control, and security.

74.2.3 Certified Information Security Manager (CISM).

The Certified Information Security Manager (CISM) is achieved similarly to that of the CISA. The Information Systems Audit Control Association (ISACA) administers and monitors this certification. CISM was created for experienced information security managers. Thus, CISM is a more specialized certification for a more defined role in the information security and assurance field.28 This qualification is for individuals who manage, design, oversee, or assess a company's information security.29 A CISM member is more of a leader in the discipline of information security, in control of other individuals who would be more suited to be qualified with a CISA certification or the like. The assurance given to employers is that they are hiring experienced professionals with the proper knowledge and ethical standing to run a secure management operation, and who have the additional ability to provide consulting advice. Like the CISA, the CISM is recognized worldwide as a top certification within the IS field.30 There are four steps required in order to achieve recognition as a CISM.

74.2.3.1 Successfully Pass the CISM Exam.

The CISM candidate must pass the exam. This exam can be taken at any time, even prior to completing necessary work experience requirements. A passed test will be valid for only five years. The rest of the requirements to become a CISM must be completed within the five-year validation period. However, once all the criteria are met within the time limit, the test does not have to be taken again. The exam is available twice a year: December and June.

The exam consists of five parts:

- Information Security Governance

- Risk Management

- Information Security Program Management

- Information Security Management

- Response Management31

More information regarding the CISM exam can be found at the CISM Exam Overview Website.32 Information can be obtained including:

- Bulletin of Information (BOI),33 which provides information on the exam

- Exam dates

- Instructions on registration

- Membership in ISACA

- Exam locations

- Candidate's Guide

- Content area (a description of certification and examination)

- Test center locations

- Exam registration

- Preparation

- Frequently asked questions

74.2.3.2 Code of Professional Ethics.

Like CISA members, all CISM members and candidates must adhere to ISACA's Code of Professional Ethics.34 This guide is to promote professionalism and standards of personal conduct. ISACA requires standards to be set for each of their members and for those nonmembers who have certifications through their program.

74.2.3.3 Continuing Education Policy.

The Continuing Education Policy for CISMs works like that for CISAs. Member maintenance fees and a minimum of 20 hours of CPE are annually required. Over a three-year period, at least 120 hours of CPE are required. By request, the ISACA will provide information and criteria for each member's personal CPE. The objectives of the CISM CPE policy are:

- Maintain an individual's competency by requiring the update of existing knowledge and skills in the areas of information systems auditing, management, accounting, and business areas related to specific industries (e.g., finance, insurance, business law, etc.)

- Provide a means to differentiate between qualified CISMs and those who have not met the requirements for continuation of their certification

- Provide a mechanism for monitoring information systems audit, and control, and for security professionals' maintenance of their competency

- Aid top management in developing sound information systems audit, control, and security functions by providing criteria for personnel selection and development35

74.2.3.4 Work Experience.

The last requirement before becoming a fully certified CISM is work experience. At least five years of experience in information security management are required and must include the five areas specified in the exam. Substitutions for this requirement can be completed by conducting two years of work as a certified CISA or CISSP in good standing, or by completing a postgraduate degree in information security or in a related field. Another credit toward the requirement can be obtained for a year of work as an information systems manager while holding a skill-based security certification (GIAC, MCSE, or CompTIA Security +).36

Once these requirements are met, a CISM Application for Certification must be completed and sent in for review by members of a CISM board through ISACA. Annual certification maintenance fees apply.37

74.2.4 Certified Information Systems Security Professionals (CISSP).

The International Information Systems Security Certification Consortium, the (ISC)2 established the Certified Information Systems Security Professional (CISSP) designation in the 1990s as a result of intense committee work by security experts. They consulted many texts and used their own experience in defining the Common Body of Knowledge (CBK) on which the examinations are based. In the decade since the certification was introduced, over 50,000 professionals have been certified.

According to (ISC)2, a CISSP is typically responsible for “developing the information security policies, standards, and procedures and managing their implementation across an organization.”38

The main requirements for being a certified CISSP are that the candidate must have at least four years of work experience in the discipline of information systems security within one or more of the 10 test domains in the ISS Common Body of Knowledge (CBK) or at least three years of such experience if the candidate has a four-year college degree. “Additionally, a Master's Degree in Information Security from a National Center of Excellence can substitute for one year toward the four-year requirement.”39

The CISSP member or candidate must subscribe to the (ISC)2 code of ethics. Like all codes of ethics, this standard is set to ensure that all members of this esteemed certification meet the highest standards of professionalism and adhere to a strict code of moral ethics.40

As with other certifications, a candidate must pass an exam; in this case, it is a six-hour exam consisting of 250 multiple-choice questions. The exam covers topics such as Access Control Systems, Cryptography, and Security Management Practices. The test is administered by the (ISC)2. The exam cannot be taken until all prerequisite requirements are completed. To obtain certification the candidate must41:

- Pass the CISSP exam with a scaled score of 700 points or better.

- Submit a properly completed and executed Endorsement Form.

- The candidate must have a CISSP application endorsed by another credentialed CISSP.

- If required, the candidate must pass an audit that asserts professional experience.

- A percentage of CISSP candidates will be chosen randomly for audit of their professional experience.

- If the candidate is up to spec, then certification will be received within seven days.

All CISSP members must then recertify their credentials every three years by completing least 120 CPE credits and a paying a fee.

74.2.4.1 CISSP Concentrations.

There are three certified concentrations within CISSP:

- Information Systems Security Architecture Professional (ISSAP)

- Information Systems Security Engineering Professional (ISSEP)

- Information Systems Security Management Professional (ISSMP)

Each credentialed certification allows a CISSP to deepen his concentration and specialty into a specified field.

Each concentration stresses a number of domains in regard to each individual field. These domains define what is expected of a candidate or member of each concentration and what professional expertise is expected.

74.2.4.1.1 ISSAP42.

ISSAP concentration focuses in the direction of security architecture and security planning:

- Access Control Systems and Methodology

- Telecommunications and Network Security

- Cryptography

- Requirements Analysis and Standards, Guidelines, Criteria

- Technology Related Business Continuity Planning (BCP) and Disaster Recovery Planning (DRP)

- Physical Security Integration

74.2.4.1.2 ISSEP43.

The ISSEP concentrates more heavily on national security and works particularly well with government branches such as the NSA:

- Systems Security Engineering

- Certification and Accreditation

- Technical Management

- U.S. Government Information Assurance Regulations

74.2.4.1.3 ISSMP44.

As the name implies, the ISSMP concentration focuses on security management and regulations:

- Enterprise Security Management

- Enterprise-Wide System Development Security

- Overseeing Compliance of Operations Security

- Understanding Business Continuity Planning (BCP), Disaster Recovery Planning (DRP), and Continuity of Operations Planning (COOP)

- Law, Investigations, Forensics, and Ethics

74.2.4.1.4 Obtaining Certification.

All three of the CISSP concentrations are obtained in the same manner. The candidate must be a CISSP in good standing, must pass an exam (ISSAP, ISSEP, or ISSMP specific), and must subsequently maintain the credential in good standing.45 The (ISC)2 organization proctors these exams.

For those interested, the (ISC)2 offers concentration review seminars that can be found on their Web site (www.isc2.org). These seminars can be found throughout the United States and Europe. Any information regarding time, place, and price can be found at the (ISC)2 Web site.

74.2.5 Systems Security Certified Practitioner (SSCP).

The Systems Security Certified Practitioner (SSCP) certification is designed for a group of acknowledged professionals within the network and security administration discipline who may not yet qualify for the CISSP designation. The focus of this certification is based upon seven test domains46:

- Access Controls

- Administration

- Audit and Monitoring

- Risk, Response, and Recovery

- Cryptography

- Data Communications

- Malicious Code/Malware

The SSCP certification is provided and authorized by the International Information Systems Security Certification Consortium (ISC)2. Candidates and members are required to adhere to the (ISC)2 code of ethics. They must have a minimum of one year of work experience in any one of the above-mentioned test domains. Also, an SSCP specified exam must be taken and passed.

This exam is made up of 125 multiple-choice questions in which all seven test domains are covered.

The American Society for Industrial Security International (ASIS) Certified Protection Professionals are considered to be in the top tier of professional practitioners of information security with an emphasis on protecting people, property, and information. Becoming a CPP is actually an award granted based on experience, education, and the passing of an exam. As of 2007, there were 10,000 people recognized as professional CPPs.

Candidates wishing to obtain this certification must meet these security and educational requirements47: Either

- Nine years of security experience, with a minimum of three years in a managerial role in charge of security or

- A BA or higher with seven years of experience in the security field and a minimum of three years in a managerial role in charge of security

Candidates who believe they meet these requirements stated must send in an application to ASIS, where it will be reviewed and notification will given if the applicant is eligible to take the CPP exam.

74.2.6 Global Information Assurance Certification.

In 1989, the SysAdmin, Audit, Network, Security Institute (SANS) began working to provide research and education resources in security.

The Global Information Assurance Certification (GIAC) was founded in 1999 to validate the real-world skills of IT security professionals. GIAC's purpose is to provide assurance that a certified individual has practical awareness, knowledge and skills in key areas of computer and network and software security. GIAC currently offers certifications for over 20 job-specific responsibilities that reflect the current practice of information security. GIAC is unique in measuring specific knowledge areas instead of general purpose information security knowledge.48

74.2.6.1 GIAC Overview.

The GIAC is a valuable addition to any other certification. Whereas other certifications provide that the member is knowledgeable and capable in her role as an information security expert, and is someone who lives up to a standard of ethics, the GIAC compounds these qualifications with a set of usable skills assuring any potential employers that the persons they are looking at are capable of carrying out information security needs. The GIAC is a good certification by itself, but it works well with any other certification such as the CISSP.

What makes GIAC a unique certification compared to other certifications is its scope and focus. The GIAC is more concerned with a variety of skill sets whereas other certifications focus on general-purpose security knowledge.49 These skill sets are:

- Security Administration

- Management

- Audit

- Software Security

GIAC certification lasts for four years, thus ensuring that all GIAC members stay current with rising concerns, new skill sets, and an evolved course base.

74.2.6.2 GIAC Certifications and Certificates.

A GIAC designation is not a set standard of practiced and learned protocols. Instead SANS offers a number of certifications and certificates that are dedicated to different areas that require information security and different skill sets. Divided into divisions—Audit, Legal, Management, Operations, Security Administration—the certificates are further divided into levels (basic to more advanced skill sets). In order to attain a GIAC certification, a five- or six-day SANS Training course must be taken followed by an exam. The exam can be taken within a six-month period from the end of the course.

74.2.6.2.1 Silver Certification.

The exam is taken online and consists of 50 to 100 multiple-choice questions and must be completed within 60 to 90 minutes. The cost of a GIAC certification is the same whether the candidate chooses self-study or conference training. Upon successful completion of the exam, a Silver certification is given to the candidate.

74.2.6.2.2 Gold Certification.

The Silver certification can be further upgraded to a Gold certification two years or more after completing the Silver certification process. Upgrading requires completion of a technical paper related to the candidate's Silver certification. The paper must be completed in a six-month period, although a three-month extension can be added for an extra fee. When the paper is submitted, it is reviewed using a number of criteria:

- Technical—errors

- Education—clarity of thought and advanced knowledge of subject matter

- Extension—a topic outside the box of normal course studies

- Organization—paper clarity, setup, and professional work50

74.2.6.2.3 Certificates.

Certificates are also offered by SANS as part of the GIAC certification. Certificates are different from certification in that they are based on shorter classes (one to two days), shorter tests that must be completed sooner (no more than 10 weeks after the completion of the course). Most important, a certificate is more focused on a particular topic area than a certification. With certificates, GIAC candidates can modify their direction and knowledge base toward the topics in which they are particularly interested or that are directly related to their work. The certificates fall into the same five categories as certifications—Audit, Legal, Management, Operations, and Security Administration—and have varying knowledge levels (introduction to advanced).

74.3 PREPARING FOR SECURITY CERTIFICATION EXAMINATIONS.

The key to passing the security certification exams is daily attention to expanding one's exposure to interesting and thought-provoking information and ideas in the field. Cramming does not work; it is not possible to remember what is learned in a rush for very long. Indeed, all students should learn to use SQ3R (survey/question, read/recite, review) a well-established study method that pays off with long-term integration and retention of knowledge. Readers may want to use a one-page summary of this technique.51 Granted, some test takers enroll in short courses (boot camps) devoted to preparing for specific certifications, but without long-term commitment to professionalism, such efforts result in a certificate that raises eyebrows among employers and clients when the crammer fails to display an ingrained understanding of soon-forgotten concepts and terminology.

Anyone committed to professionalism and long-term success in a field should read a wide range of reputable publications and participate in serious discussion groups.

74.3.1 Newsletters.

Some of the electronic newsletters useful for anyone preparing for certification exams are listed next:

- Computerworld newsletters: www.computerworld.com/action/member.do?command=registerNewsletters

- Disaster Recovery

- Infrastructure & Control

- Networking Security

- Security: Issues and Trends

- Virus and Vulnerability Roundup

- CRYPTO-GRAM from Bruce Schneier: www.schneier.com/crypto-gram.html

- Department of Homeland Security resources: www.dhs.gov/xinfoshare/programs/

- Homeland Security Advisories and Information

- Daily Open Source Infrastructure Report

- EFFector from the Electronic Frontier Foundation: www.eff.org/effector/

- EPIC Alert from the Electronic Privacy Information Center: www.epic.org/alert/

- Network World Newsletters: www.networkworld.com/newsletters/

- Security: Identity Management Alert

- Security: Network Access Control Alert

- Security: Threat Alert

- Security Strategies Alert

- ITL Computer Security Bulletins from the National Institute of Standards and Technology Information Technology Laboratory Computer Security Division's Computer Security Resource Center keep readers abreast of new documents issued by NIST: http://csrc.nist.gov/publications/nistbul/index.html

- RISKS FORUM DIGEST from the Association for Computing Machinery Committee on Computers and Public Policy: http://catless.ncl.ac.uk/Risks/

- SANS newsletters: www.sans.org/newsletters/?ref=1701

- @RISK: The Consensus Security Vulnerability Alert

- NewsBites

- ZDNet UK newsletters: http://community.zdnet.co.uk/account/manage.htm

- “IT White Papers”

- “Security”

74.3.2 Web Sites.

The National Institute of Standards and Technology Information Technology Laboratory Computer Security Division's Computer Security Resource Center has a several good resources for review by anyone taking security certifications.

First, the NIST Special Publications (SP) page—http://csrc.nist.gov/publications/PubsSPs.html—has a wealth of valuable papers for anyone interested in reviewing and extending security knowledge, especially security-management knowledge.

A related page is the NIST ITL CSD CSRC Draft Publications list, http://csrc.nist.gov/publications/PubsDrafts.html, which offers even more recent documents plus the opportunity for certification preparers to apply their analytical skills to improving proposed documents. Some of the drafts are also linked from the previously mentioned SP page, but on the draft page each is described in a one-paragraph summary that includes the deadlines for comments.

Even if certification candidates are not currently working in the U.S. federal government, they would do well to read many of the Federal Information Processing Standards (FIPS) available from the NIST ITL CSD CSRC (http://csrc.nist.gov/publications/PubsFIPS.html).

A collection of interesting white papers on security-related topics is maintained by Entrust: www.entrust.com/resources/whitepapers.cfm. At latest count, there are over 100 papers freely available from that source (some of them in German) without having to sign up for anything. Some of the papers readers may find valuable in stimulating their thinking about security fundamentals:

- AITE Online Banking Security: FFIEC Deployment Experiences

- An Introduction to Cryptography and Digital Signatures v2.0

- Authentication: The Cornerstone of Secure Identity Management

- Best Practices for Choosing a Content Control Solution

- Common Criteria Evaluation

- Countering On-Line Identity Theft: New Tools to help Battle Identity Theft on the Internet

- Did Security Go Out the Door with Your Mobile Workforce?

- Enhanced Online Banking Security—Behavioral Multi-Factor Authentication

- Entrust Internet Security Survey—European Survey Overview and Report Methodology

- GIGA Report: Total Economic Impact of Entrust TruePass and Token-based Authentication

- Information Security Governance: Toward a Framework for Action (BSA white paper)

- Myths and Realities in Content Control for Compliance

- Protecting Information on Laptops and Mobile Devices

- Quantum Computing and Quantum Cryptography

- Security in a Web Services World

- Trends in Outbound Content Control: A White Paper by Ferris Research

- Trusted Public-Key Infrastructures

- Understanding Secure Sockets Layer (SSL): A Fundamental Requirement For Internet Transactions

- Using a PKI Based Upon Elliptic Curve Cryptography

- Web Portal Security Solution

- Web-Services Security Quality of Protection.

74.3.3 CCCure.org.

The CCCure.Org site run by Clément Dupuis and Nathalie Lambert—www.cccure.org—is rich in resources for anyone preparing for a security-certification exam.

The Web site started in 2001 when Clément was working in Montréal, Canada, after a 20-year career in military communications and security in the Canadian Army. He was certified as a CISSP in 1999. Clément and his friend Chris Hare decided to create study guides for several of the domains from the Common Body of Knowledge (CBK), www.isc2.org/cgi/content.cgi?category=8; they then put them on the Web for anyone to use. That was the birth of what became CCCURE.ORG. It became so popular that it was kicked off several hosting sites because it generated too much traffic for a free service. Clément and his wife, Nathalie Lambert, a mechanical engineer who became an expert in programming and networking, had to convert it into a commercial venture. However, in addition to monetary contributions by a few carefully selected advertisers, it is supported by the work and enthusiasm of thousands of volunteers.52

The CCCure home page is extensive; it includes a great deal of material for anyone to soak up, lots of interesting knowledge and ideas, and the ability to contribute insights. In particular, the Quiz section has an excellent review tool that generates questions for several certifications including the CISSP, CISA, SSCP, and GSEC; readers can choose the domain(s), topics, difficulty level, whether to include related questions, and the number of questions. The quiz generator creates a unique, randomized quiz at every iteration. It is a valuable tool because it forces active recall and application of the knowledge you are trying to consolidate. Indeed, a recent article in ScienceNow from the American Association for the Advancement of Science indicates that testing improves retention not only of the material tested but of other information being learned at the time of the test.53

The CCCure.org site features a list of suggested readings and a forum where participants can engage in spirited discussion of technical issues relating to their exam preparation.

74.3.4 Books and Free Review Materials.

Some of the most useful books for overall coverage of the field are:

- The Official (ISC)2 Guide to the CISSP® Exam by Susan Hansche, CISSP, John Berti, CISSP, and Chris Hare, CISSP (ISBN: 0-8493-1707-X) is available from the (ISC)2 Company Store,

- Information Security Management Handbook on CD-ROM, 2006Edition (a classic in the field) by Harold F. Tipton and Micki Krause,

- Handbook of Information Security, 3-volume set (chosen as a textbook for the master's program in information assurance at Norwich University) by Hossein Bidgoli, http://tinyurl.com/yf2549 or www.networkworld.com/newsletters/sec/2006/0410sec2.html

- Computer Security Handbook, 5th edition edited by Bosworth, Kabay, and Whyne, which you are currently reading

In addition, the (ISC)2 provides a slightly disorganized list of books at www.isc2.org/cgi-bin/content.cgi?category=698.

Ideally, people preparing for any exam do best if they can study in teams. For example, they can use lecture slides as review material to quiz each other—they should be able to speak intelligently about every point on every slide. The files thus serve as one of the ways to check for holes in coverage of the material and also as a way of consolidating and strengthening knowledge. Searching on “security course slides” in a Web search engine brings up many possible sites for such materials. These are intended for educational purposes in college and university courses, but they serve admirably as preparatory and review materials for professionals approaching exams. Security-course slides available from the Web site of one of the authors include:

- I340 Intro to IA lectures: www2.norwich.edu/mkabay/courses/academic/norwich/is340/lectures.htm. The course covers some of the subjects in Volume I of this Handbook (although the chapter headings refer to the fourth edition).

- IS342 Management of IA: www2.norwich.edu/mkabay/courses/academic/norwich/is342/Lectures/index.htm. This course covers many of the topics in Volume II of this Handbook (again, the chapter headings refer to the fourth edition).

- CJ341 Cybercrime & Cyberlaw: www2.norwich.edu/mkabay/courses/academic/norwich/cj341/Lectures/lectures.htm. This course is taught for the Department of Criminal Justice at Norwich University by Professors Kabay, Stephenson, and Towers. The course materials offer a detailed look at intellectual property, defamation, computer trespass, and how law enforcement has to deal with digital evidence, including the specific laws relating to computer crimes of all sorts. “Legal, Regulations, Compliance and Investigations” is one of the 10 domains of the CBK (Common Body of Knowledge) for the CISSP: www.isc2.org/cgi/content.cgi?category=8.

In addition to all of this free knowledge, it is also possible to enroll in a wide range of preparatory courses. However, one should be leery of taking a short course instead of reading and thinking for a long time about any subject beyond the purely technical. The most important aspect of learning is thinking, not memory. Take a course if you like, but not just before your exam. Use the course as a form of review and verification—a tool for strengthening what you already know, but above all for identifying what you have to think and learn about at greater length.

74.4 COMMERCIAL TRAINING IN INFORMATION ASSURANCE.

There are many courses offered in information assurance at different levels; most of them concentrate on technical subjects. In this section, we review some of the best-known offerings.

74.4.1 Security University Classes and Certifications.

Security University is setting a new Security certification standard by being “Qualified” to competently complete a job or task with skills validation. Security University is grouping SU Security Certifications into exam-based and education-based (skills validation) certifications.

Exam-based certifications. A person is certified as being able to competently complete a job or task, usually by the passing of an examination, which can also be learned by self-study with no classroom requirement.

Education-based certifications are instructor-led sessions, where each course has to be passed and hands-on labs must be competently completed to provide skills validation.

Tactically trained security professionals are in demand. CISSPs armed with a Q/ISP (Qualified/Information Security Professional) can prove they know the “how to” of the computer security business as well as risk mitigation. The founder, Sondra Schneider, offers a perspective on her philosophy of hands-on security education and training.54

Not only is it important to seek courses with direct benefit to daily activities but it is also critical to invest in tactical security skills. Tactical security skills are the “how to” security skills such as how to provide defense in depth through technical diversity, incident response, security awareness, hack, code analysis, write secure software and applications and lastly how to do black-box testing (assessments) of wired and wireless networks, software and applications.

How does one learn tactical security skills? Security University provides highly focused Tactical Security training for one or many tactical security skills. Security University Qualified/Information Security Professional (Q/ISP) certification consists of completing four classes and one workshop that transfer a multitude of tactical security skills to the student. From the moment students enter a class, they are working on the practice and are challenged by qualified instructors who have mastered their Tactical Security skills to the highest degree.

The new Qualified/Software Security Expert (Q/SSE) certification sets the new standard in developing new active skills that can be immediately applied to the workplace. The Q/SSE boot camp uncovers exactly how coding can and will become the next hacking frontier.

Hacking is an art and a science. Creating exceptions in live systems yields unauthorized access to networks and applications. Armed with any one of the Tactical Security skills, students exceed general theories. Generalized training sets a foundation. Combining a foundation, like that of the CISSP, with the capability to apply skills helps candidates achieve career goals and success while learning how a hacker thinks.

In the next years, more companies will discover that black box testing only reveals 15% of their vulnerabilities. Only through tactical code analysis and software testing skills can you elevate your level of assurance that you have done what is necessary to keep the hackers off your networks. Security University's Qualified Training programs work because they make the student produce work, so they leave with new usable skills. Security University's training provides excellent return on investment because it is methodology driven. Specific technology may become outdated; however by learning methodologies the tactical security skill set can be automatically transferred to replacement technologies since the student truly understands what to do and where to go in any related situation.

Security University offers a wide range of computer security classes, exams, and education certifications:

- Qualification & Certification Tracks

- SU Q/ISP Qualified/Information Security Professional (four classes, one workshop)

- QISP001 ECSA Prep & Qualified/Security Analyst Penetration Tester

- QISP002 LPT & Qualified/Penetration Tester License Workshop

- QISP003 CEH Prep & Q/EH Qualified Ethical Hacker/Network Defender

- QISP004 Q/EP Qualified Edge Protector

- QISP005 CHFI Prep and Q/FE Qualified/Forensic Expert

- SU Q/IAP Qualified Information Assurance Professional (three classes)

- QIAP001 Q/AAP Qualified Access, Authentication & PKI Professional

- QIAP002 Q/NSP SOA Qualified Network Security Policy Administrator and Security Services Oriented Architect

- QIAP003 Q/CA Qualified/Certification and Accreditation Administrator class

- SU Q/ISP Qualified/Information Security Professional (four classes, one workshop)

- Computer Security Introduction classes

- QSAP001 Qualified Internet Threat Security Awareness Training and Compliance for MGT

- QSAP002 Qualified Security Awareness Training

- SSCP001 Security + and SSCP Bootcamp

- SSCP002 SSCP System Security Certified Professional

- QISP006 Catching the Hackers—Introduction to Intrusion Detection

- QSAP003 Qualified Security Awareness Defender Certificate for Managers

- SU CWNP Wireless Certifications

- SU EC-Council Certifications

- EC001 CEH Prep—Ethical Hacking Certification

- EC002 ECSA Prep EC—Council Security Analyst

- EC003 LPT License Penetration Tester

- EC004 CHFI Prep—Computer Hacking Forensic Investigator

- Specialty Security Classes

- ISC2001 CISSP ISC2 Certification Review Class

- QIAP004 DoD Information Technology Security Certification and Accreditation Process DITSCAP

- QIAP005 Mission Critical Planning (Hands On)

- QISP007 Linux/UNIX Security

- QISP008 Catching the Hackers II: Systems to Defend Networks

- SU QSSE Qualified Software Security Expert

- QSSE001 Qualified Software Security Expert 5 Day Bootcamp

- QSSE002 Qualified Software Security Penetration Tester

- QSSE003 Software Testing Bootcamp

- QSSE004 How to Break & FIX Web Security

- QSSE005 How to Break & FIX Software Security

- QSSE006 Fundamentals of Secure Software Programming

- QSSE007 Qualified Software Hacker/Defender

- QSSE008 Qualified Software Tester Best Practices

- QSSE009 Introduction to Reverse Engineering

74.4.2 Getronics Security University55.

Another resource for professionals looking for security education is Getronics Security University. Working with (ISC)2 as a registered provider of CPEs for CISSP and SSCP holders, the company offers 38 short online courses lasting from 15 minutes to 5 hours.56 Courses include:

- 010 Information Security Essentials (15 minutes)

- 028 Laptop Security Essentials (15 minutes)

- 081 Information Privacy Essentials (20 minutes)

- 082 Identity Theft Essentials (20 minutes)

- 101 Introduction to Computer Crime (2 hours)

- 110 Introduction to Information Security (1.3 hours)

- 112 Risk Management (1 hour)

- 113 Information Ownership, Valuation, and Classification (1 hour)

- 114 Social Engineering (1 hour)

- 115 Information Security Policies (1 hour)

- 119 eCommerce Security Fundamentals (1 hour)

- 128 Information Security for Remote Users (2 hours)

- 130 Access Control (1 hour)

- 142 Networks and Telecommunications (1 hour)

- 147 Introduction to Wireless Security (1 hour)

- 150 Business Continuity Planning (1 hour)

- 160 Incident Response (1 hour)

- 161 Malware Basics (1 hour)

- 163 Introduction to Computer Investigations (1 hour)

- 170 Introduction to Cryptography (1 hour)

- 171 Basic Concepts of Cryptography (1 hour)

- 177 Introduction to Public Key Infrastructure (2 hours)

- 181 Information Privacy (1 hour)

- 182 Identity Theft (1 hour)

- 184 Cybersafety (1 hour)

- 191 Computer Room Security (1 hour)

- 231 Network Access Controls (2 hours)

- 232 Firewalls (2 hours)

- 233 Virtual Private Networks (2 hours)

- 243 Database Security (2 hours)

- 244 Introduction to Web Application Security (5 hours)

- 247 Wireless Network Security (5 hours)

- 261 Intrusion Detection in Networks (5 hours)

- 262v2 Fighting Malware (3 hours)

- 277 Intermediate Public Key Infrastructure (PKI) (5 hours)

- 282 Understanding Due Care, Due Diligence, and Negligence (2 hours)

- 382 Executive Review GLBA, SOX, SB1386 (15 minutes)

- 482 NIST SP800 50 (building awareness & training programs) (4 hours)

Per-student and institutional licenses are available for these courses.

74.4.3 CEH Franchise.

The International Council of Electronic Commerce Consultants (EC-Council) was created to “support and enhance the role of individuals and organizations who design, create, manage or market Security and E-Business solutions.”57 The EC-Council has established a number of certifications:58

- Entry-Level Security Certifications

- Security 5

- Network 5

- Wireless 5

- IT Security Professional Certifications

- CIEH Certified Ethical Hacker

- CIHFI Computer Hacking Forensic Investigator

- EICSA EC-Council Certified Security Analyst

- CINDA Certified Network Defense Architect

- LIPT Licensed Penetration Tester

- EICVP EC-Council Certified VOIP Professional

- EC-Council Network Security Administrator

- EC-Council Certified Computer Investigator

- Disaster Recovery and Business Continuity

- EC-Council Disaster Recovery Professional

- Programming Certifications

- EICSP EC-Council Certified Secure Programmer

- CISAD Certified Secure Application Developer

- Graduate-Level Certifications

- Fundamentals in Computer Forensics

- Fundamentals in Information Security

- Fundamentals in Network Security

- EICSS EC-Council Certified Security Specialist

- E-Business Certification

- CIEP Certified e-Business Professional

The EC-Council has licensed its courses to dozens of organizations around the world. Readers will have no difficulty finding resources by contacting the organization directly.59

74.5 CONCLUDING REMARKS.

This chapter cannot provide an exhaustive listing of training and certification resources. Practitioners should monitor the trade press for indications of trends in acceptance of new certifications and should judge how to keep themselves at the forefront of the field through continued professional development. In addition, professionals may find it satisfying, personally educational, and even moderately lucrative to involve themselves in training and certification as teachers. At the least, holders of professional certifications should consider serving as proctors for examinations so that their associations can continue offering these valuable indicators of professional knowledge without having to depend on government and industry handouts.

74.6 NOTES

1. Microsoft® Encarta® Dictionary 2008.

2. NOCA general information: www.noca.org/GeneralInformation/AboutUs/tabid/54/Default.aspx.

3. NCCA Accreditation: www.noca.org/Resources/NCCAAccreditation/tabid/82/Default.aspx

4. IACE Program: www.nsa.gov/ia/academia/iace.cfm.

5. Centers of Academic Excellence: www.nsa.gov/ia/academia/caeiae.cfm.

6. I. Armstrong, “Money Matters: SC Magazine/EC-Council Salary Survey 2007,” SC Magazine, April 1, 2007; www.scmagazineus.com/Money-matters-SC-MagazineEC-Council-Salary-Survey-2007/article/34874/.

7. M. Savage, “Get Qualified: Certification—That's the Name of the Game,” SC Magazine, November 1, 2003; http://scmagazine.com/asia/news/article/419631/get-qualified-certification-thats-name-game/.

8. A. Saita, “The CISSP Receives International Standardization,” SearchSecurity.com, June 23, 2004; http://searchsecurity.techtarget.com/original-Content/0,289142,sid14_gci989901,00.html.

9. (ISC)2, DoD Fact Sheet, 2007: www.isc2.org/cgi-bin/content.cgi?page=949.

10. C. Hildebrand, “Forecast 2008: Information Security Goes Strategic.” InfoSecurity Professional (Spring 2008): 4–7. https://www.isc2.org/cgi-bin/securedocument.cgi?id=15.

11. CIA Home Web Page: www.theiia.org/?doc_id=3.

12. CIA Home Web Page.

13. IIA Approved “Character Reference for CIA Candidate”: http://www.theiia.org/download.cfm?file=10037

14. CIA Home Web Page.

15. NOCA general information: www.noca.org/GeneralInformation/AboutUs/tabid/54/Default.aspx.

16. IIA Approved “Character Reference for CIA Candidate.”

17. IIA Approved Code of Ethics: www.theiia.org/?doc_id=604.

18. IIA Approved “Character Reference for CIA Candidate.”

19. CIA Exam Content: www.theiia.org/certification/certified-internal-auditor/cia-exam-content/.

20. Specialty certifications: www.theiia.org/certification/specialty-certifications/.

21. CIA 2008 Candidate Handbook: www.theiia.org/download.cfm?file=75018.

22. ISACA® Web page, CISA Certification: www.isaca.org/Template.cfm?Section=CISA_Certification&Template=/TaggedPage/TaggedPageDisplay.cfm&TPLID=16&ContentID=4526.

23. Savage, “Get Qualified.”

24. ISACA Code of Professional Ethics: www.isaca.org/Template.cfm?Section=Code_of_Professional_Ethics1&Template=/ContentManagement/ContentDisplay.cfm&ContentID=20454.

25. CPE Policy Guideline: www.isaca.org/Template.cfm?Section=Continuing_Education_Policy&Template=/TaggedPage/TaggedPageDisplay.cfm&TPLID=28&ContentID=20482.

26. Standards, Guidelines, and Procedures: www.isaca.org/Template.cfm?Section=Standards&Template=/TaggedPage/TaggedPageDisplay.cfm&TPLID=29&ContentID=6707.

27. Application for Certification and Maintaining Certification: www.isaca.org/Template.cfm?Section=CISA_Certification&CONTENTID=20473&TEMPLATE=/ContentManagement/ContentDisplay.cfm.

28. ISACA Homepage, CISM Certification Web page: www.isaca.org/Template.cfm?Section=CISM_Certification&Template=/TaggedPage/TaggedPageDisplay.cfm&TPLID=16&ContentID=4528.

29. IIA Approved “Character Reference for CIA Candidate.”

30. B. Brenner, “Numbers: ISACA Says Survey Illustrates Benefits of CISM Cert: A Recent Survey Backs the Notion that CISMs Are in a Better Position to Deal with a Growing Emphasis on Business Needs over Technology, an ISACA Official Says,” CSO Magazine, June 5, 2008; www.csoonline.com/article/379914/Numbers_ISACA_Says_Survey_Illustrates_Benefits_of_CISM_Cert.

31. CISM Certification Content Area: www.isaca.org/Content/NavigationMenu/Security/CISM_Certification/Exam_Information1/Content_Areas1/CISM_Certification_Content_Areas.htm.

32. CISM Exam Overview: www.isaca.org/Template.cfm?Section=CISM_Certification&CONTENTID=20608&TEMPLATE=/ContentManagement/ContentDisplay.cfm.

33. CISM Bulletin of Information: www.isaca.org/Template.cfm?Section=Bulletin_of_Information1&Template=/ContentManagement/ContentDisplay.cfm&ContentID=20611.

34. Hildebrand, “Forecast 2008.”

35. Requirements for CISM Certification: www.isaca.org/Template.cfm?Section=CISM_Certification&CONTENTID=20681&TEMPLATE=/ContentManagement/ContentDisplay.cfm.

36. IIA Approved “Character Reference for CIA Candidate.”

37. CISM Application and Maintenance: www.isaca.org/Template.cfm?Section=Application_and_Maintenance1&Template=/ContentManagement/ContentDisplay.cfm&ContentID=20683.

38. CISSP, About Certification Web page: http://certification.about.com/od/certifications/p/cissp.htm.

39. CISSP Professional Experience requirement - https://www.isc2.org/cgi/content.cgi?category=1187

40. CISSP Code of Ethics: www.isc2.org/cgi/content.cgi?page=31.

41. CISSP Exam Information: www.cissp.com

42. ISSAP Information Page: www.isc2.org/cgi-bin/content.cgi?category=522.

43. ISSEP Information Page: www.isc2.org/cgi-bin/content.cgi?category=523.

44. ISSMP Information Page: www.isc2.org/cgi-bin/content.cgi?category=524.

45. (ISC)2 Web site—ISSAP, ISSEP, ISSMP Credentials: www.isc2.org/cgi-bin/content.cgi?category=99.

46. SSCP Webpage: http://certification.about.com/od/certifications/p/sscp.htm.

47. ASISI Certified Protection Professional Web page: www.asisonline.org/certification/cpp/index.xml.

48. GIAC Home Web page: www.giac.org.

49. GIAC Program Overview: www.giac.org/overview/.

50. GIAC Gold Certification Web page: http://www.giac.org/gold.

51.www2.norwich.edu/mkabay/methodology/sq3r and in PDF www2.norwich.edu/mkabay/methodology/sq3r.pdf.

52. For more about the history and philosophy of CCCure.Org, see www.cccure.org/modules.php?name=News&file=article&sid=397.

53. J. Cutraro, “Testing Boosts Memory,” ScienceNow, November 13, 2006; http://sciencenow.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/2006/1113/2.

54. Security University home page: www.securityuniversity.net/.

55. Getronics Security University home page: https://gsuonline.com/main.htm.

56. Getronics Security University course catalog: https://gsuonline.com/coursecatalog.htm.

57. EC-Council FAQ: www.eccouncil.org/faq.htm.

58. EC-Council certifications: www.eccouncil.org/certification.htm.

59. EC-Council Accredited Training Provider: www.eccouncil.org/atp.htm.