CHAPTER 64

U.S. LEGAL AND REGULATORY SECURITY ISSUES

Timothy Virtue

64.2 SARBANES-OXLEY ACT OF 2002

64.2.2 Management Perspectives on SOX

64.3.3 Consumers and Customers

64.1 INTRODUCTION.

The regulatory requirements facing today's business leaders can strengthen the overall business environment while offering increased safeguards to stakeholders such as consumers, suppliers, shareholders, employees, and other interested parties transacting with today's businesses. Although regulatory requirements vary from institution to institution and across different industries, the recurring theme is that management must be proactively involved and fully accountable for the actions of its organization.

Compliance is an ongoing process that can be achieved successfully only when the organization's senior leaders support compliance from both a cultural and operational perspective. In other words, the right attitudes (integrity, honesty, transparency, etc.), also known as tone at the top, must be exemplified in all facets of the organization while working in tandem with operational processes to create a comprehensive compliance environment. A culture of compliance must be integrated throughout the organization and must be seamlessly built into all operational facets of the business.

Many organizations are restructuring independent and isolated operational units (sometimes described as silos) and focusing on coordinated strategic risk management for the enterprise. Such changes support business values, achieve compliance, and reduce risk.

Another recurring theme of today's regulatory environment is accountability for, and protection of, sensitive or private information. Specific regulatory requirements and how an organization addresses the requirements will vary, based on industry, organizational structure, and internal processes. However, an effective enterprise-wide regulatory-governance model should incorporate two common elements:

- The senior management team must create a compliance-driven culture by actively exercising leadership by example.

- The team must actively support this culture of compliance by enabling computer security strategies, tactics, and technologies as discussed throughout this Handbook.

Compliance with regulatory requirements must include, but is not limited to, these computer security fundamentals:

- Program management

- Policy and procedure design and implementation

- Risk assessment and management

- Prevention

- Detection

- Response

- Implementation of safeguards

- Administrative controls

- Physical controls

- Technical controls

- Awareness and training

Although there are a number of regulations that today's business leaders may be accountable for, these requirements vary from industry to industry. This chapter focuses on two important U.S. regulations: the Sarbanes-Oxley and the Gramm-Leach-Bliley acts. These particular acts require a significant level of management involvement in order to validate that the organization adequately addresses the regulatory requirements.

64.2 SARBANES-OXLEY ACT OF 2002.

Although a comprehensive discussion of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 (SOX) is outside the scope of this text, a high-level understanding of the key components is required so that management may adequately fulfill its responsibilities under this act. SOX is made up of 11 titles and is administered by the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). The main goal of the legislation, also sometimes referred to as the Public Company Accounting Reform and Investor Protection Act of 2002, is to protect the public and shareholders from accounting errors and fraudulent practices by requiring that companies monitor and record any access to sensitive financial data. They must provide reports on their controls, and must respond in a timely and appropriate manner should an incident occur.1

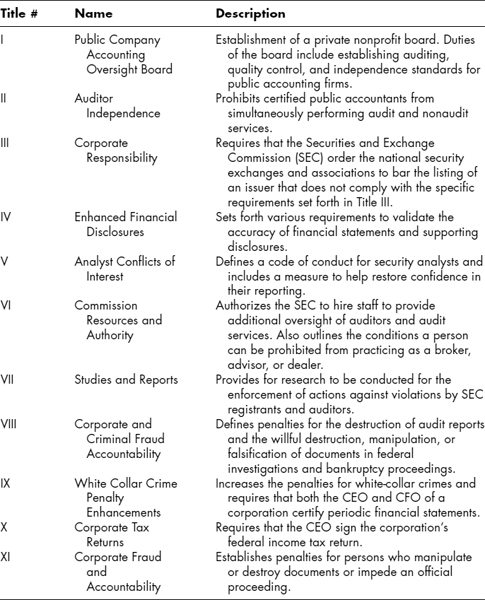

Exhibit 64.1 offers each title within SOX with a brief description added by the author.

EXHIBIT 64.1 Eleven Titles of SOX with Descriptions

All of the individual components from Exhibit 64.1 that specify the requirements for SOX must have the support and involvement of an organization's senior leadership team. It is important to note that no single component of SOX is more important than any other component. In fact, SOX derives its strength and effectiveness because this is truly a case where the whole is greater than the sum of its parts.

Although all of the components to SOX are important and require active participation by management at both a strategic and operational level, the remaining discussion focuses on the part of the act that affects computer security the most, Section 404.

The passage of SOX in 2002 led the way for an important change in how business leaders in today's public companies look at information security. This change has caused significant impact on today's information systems, the security that supports them, and management's perception of how the systems affect financial reporting. Although SOX was primarily intended to enhance the integrity of financial reporting, it has broader implications. Specifically, the integrity of financial reporting can be accomplished only by ensuring the integrity of the source information used to complete financial reporting requirements. Management must therefore support the design, implementation, and continuous management of strong controls over the information systems that are the primary source for today's financial reporting requirements.

64.2.1 Section 404 of SOX.

Since compliance with SOX is supported by the organization's ability to develop, implement, and manage a combination of business reporting requirements and management controls, many of the organization's information systems are directly or indirectly involved in the SOX compliance process. The breadth and depth of the impact will vary among different organizations but can range from end user computing applications (e.g., spreadsheets) all the way to the data center, as well as anything in between. For this reason, business leaders must address these issues and must provide adequate support to achieve continuous compliance with SOX. As referenced earlier, SOX addresses a number of areas requiring senior executive leadership and support. However, Section 404 of SOX is most relevant to information security programs, and requires businesses to:

- Evaluate the adequacy of internal controls that impact financial reporting

- Implement new controls as necessary

- Annually test and report on the assessment results of internal controls

Section 404 requires the business to implement a comprehensive internal control framework sustainable throughout the enterprise. Furthermore, these controls must not only directly protect the integrity of financial data and indirectly protect the systems that support the data, but the business is also required to show that these controls are operational and are functioning as intended. Since compliance with SOX affects the organization at an enterprise-wide level, information security protections should be designed, implemented, and managed from a holistic perspective supported by management as part of an overall business strategy, rather than as a single compliance activity. When this approach is taken, the business is better positioned to comply with SOX, to achieve compliance sustainability, and to validate that compliance is integrated throughout the entire organization.

In most organizations, almost all corporate information, including financial information, is linked to enterprise information systems. Many systems feed or share information with each other. Therefore, the organization must look at data origins, data flows, and data output to validate that they have adequately identified all of the information that could impact financial reporting. Management must provide the appropriate level of support for robust controls to protect the data resources of critical corporate information systems, which ultimately act as the primary data source the business must rely on when delivering and validating the integrity of the organization's financial statements.

With today's modern technologies pervasively deployed in business environments, organizations are likely to face a variety of SOX compliance challenges. These challenges result from the vast number of information systems, the associated supporting infrastructure, highly connected and communication intensive networks, and in many cases externally facing Web-based applications that are highly susceptible to exploitation.

Additional challenges come from the inside as well. The insider threat is quickly becoming one of the most difficult security challenges to overcome, and causes the majority of security problems for many organizations (see Chapter 45 in this Handbook). Internal data protection challenges are further complicated by the increase in privileged users such as database administrators, system administrators, and a variety of other users with powerful access to critical information systems. Such users often unknowingly create significant SOX compliance risks for their organization. These powerful privileges are often overused, and ultimately can be the pathway to noncompliance or malicious activity within the organization. Furthermore, many of these privileged users can manipulate system log files so that their malicious activity goes unnoticed or in some cases becomes untraceable (see Chapter 53).

64.2.2 Management Perspectives on SOX.

Properly administered compliance initiatives must strike a balance between information security and system usability, to support business and compliance objectives without creating an environment of distrust. Although the insider threat is a significant threat to many businesses, the senior leadership team must accept that employees are a critical component of business operations. Since management controls are intended to protect sensitive system data, and not to create a hostile work environment, SOX-related corporate policies and standards must support the spirit of the act by ensuring that organizations closely monitor and control access to critical business systems while not impeding employee productivity. Achieving this balance is not always an easy task.

Regardless of the specific strategies organizations employ to design, implement, and manage, there are some fundamental operational policies and processes that should be put in place to protect the integrity of both the data and ultimately the organization's financial reporting.

Fortunately, many organizations may find they already have a majority of the required controls in place, because many of the control requirements can be accomplished through traditional information security best practices. Some of the more common examples include controls that address segregation of duties (e.g., among development, test, and production environments) and appropriate data-security controls and safeguards.

A list of more common database safeguard components that senior management should focus on when complying with Section 404 of SOX follows.

- Monitor database access by privileged users.

- Monitor changes in privileges.

- Monitor access failures.

- Monitor schema changes.

- Monitor direct data access.

In order to get a better grasp on all of the complexity associated with database compliance challenges, senior leadership teams in many organizations elect to take a back-to-basics approach. One of the most effective strategies to deploying such a simplified approach is to use the traditional five Ws. Specifically, organizations should be asking these questions in terms of database compliance:

- Who did something to the database?

- What did they do?

- Which specific data component?

- When was the activity performed?

- Where was the information accessed?

When members of the organization's senior leadership team approach the SOX compliance issue in this manner, they are in a better position to understand, and ultimately to assume the responsibility for, the data security and integrity for which they are accountable.

The requirement of having an organization's senior management work with an external auditor to report on the internal control program is, unfortunately, the most costly requirement of SOX and requires an enormous effort.

However, organizations should also take note that there are a number of benefits from designing, implementing, and managing effective compliance strategies, beyond initial SOX compliance. Establishing a comprehensive internal controls program not only aids in SOX compliance but also forms a foundation for operational improvements. Anytime the organization's senior management team can institute an effective internal controls program, it is not only taking steps to compliance, but also building a solid foundation on which enterprise-wide data governance programs can follow.

64.3 GRAMM-LEACH-BLILEY ACT.

One of the most significant pieces of legislation to affect the financial services industry was the Financial Services Modernization Act of 1999, commonly referred to as the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act or GLBA.2 It was enacted in response to the standardization of the U.S. banking and insurance industries in the late 1990s. The financial services industry was undergoing substantial change during this period. Since financial institutions and insurance companies were allowed to merge and consolidate their operations, legislators and industry observers were concerned about providing adequate protection of consumer rights and data protection. Specifically, significant concerns developed over the consolidation of consumer data. There was substantial fear that sensitive consumer data would be openly shared among financial organizations and their subsidiaries. This open environment would likely threaten consumer rights and the security of sensitive and personal financial data. The consolidation and reform within the financial services industry was enabling the creation of new financial services holding companies that could offer a full range of financial products. Prior to the passage of GLBA, some major financial institutions were selling personal and sensitive detailed customer information to business partners. This type of disclosure often included the disclosure of account numbers and other highly sensitive data to telemarketing firms. These telemarketing agencies often used the account numbers to charge customers for products and services they did not want and that had no value to customers.

64.3.1 Applicability.

GLBA applies to U.S. domestic financial institutions; it defines financial institutions as “companies that offer financial products or services to individuals, like loans, financial or investment advice, or insurance.” GLBA coverage includes but is not limited to organizations that provide insurance, securities, payment settlement services, check cashing services, credit counselors, and mortgages.

GLBA is intended to address the proper handling of nonpublic financial information. However, senior management teams of financial institutions must acknowledge that the act also includes a wide range of information that is not obviously financial in nature. This additional coverage is intended to offer further protections to the consumer and properly align with the spirit of the law. Specifically, the additional types of information that must be protected include the consumer's name and address. However, protection may extend to:

- Information given to a financial institution in order to receive a financial product or service

- Information generated or remaining as a result of a transaction between a financial institution and a consumer

- Information obtained by the financial institution while providing a financial product or service to a consumer

As mentioned, GLBA requires financial institutions to safeguard nonpublic personal information (such as a Social Security Number, credit-card details, or a bank account number) provided by a consumer under various privacy rules or resulting from a transaction or other service performed on behalf of the consumer. This information is not necessarily considered financial information. For example, under GLBA, a consumer's name identifying a recipient of services from a specific institution is also considered nonpublic information that must be protected under GLBA. Specifically, GLBA mandates:

- Secure storage of consumer personal information

- Providing adequate and sufficient notice to consumers regarding how the financial institution shares their consumer personal and financial information

- Providing consumers with the choice to opt out of sharing their personal and financial information

64.3.2 Enforcement.

GLBA is enforced by the Federal Trade Commission (FTC), various financial industry regulators, and state attorneys general. More stringent requirements may be placed on the financial institutions by individual states, because GLBA does not preempt state law.

Although current legislation does not offer a remedy of civil action, a financial institution's failure to comply with notice is considered a deceptive trade practice by both state and federal authorities. Some states do have specific legislation that offers a private right of action for consumers.

Title V of the act provides that financial institutions may share practically any information with affiliated companies but may share information with nonaffiliated companies for marketing purposes only after providing an opportunity for the consumer to opt out of the information sharing process. Management needs to play a proactive role in providing administrative, managerial, and technical support to achieve compliance with Title V of the Act. Consumers must be provided with easy-to-understand and easy-to-use opt-out choices. Organizations that make opting out difficult, or that otherwise appear to be duplicitous, are likely to be viewed as noncompliant with Title V of GLBA.

The provisions of Title V do not preempt or supersede state law. If organizations are conducting business in a state that has more stringent requirements, then those state requirements must be met, in addition to GLBA. Section 505 requires that the act and its associated regulations be enforced by various federal and state regulatory agencies having jurisdiction over financial institutions. This requirement of GLBA offers federal enforcement authority to a variety of enforcement agencies. The more common enforcement agencies include:

- Office of the Comptroller of the Currency

- Federal Reserve Board

- Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation

- Securities and Exchange Commission

An organization's senior leadership team should also note that the Federal Trade Commission has general enforcement authority for any financial institution that does not fall within the jurisdiction of any of the specific enumerated regulatory agencies.

As previously stated, the intent of GLBA is to offer adequate protection to consumers conducting business with financial services firms. Although the hope is that organizations will comply with GLBA on goodwill, the act was created with some serious repercussions to financial institutions that do not comply. GLBA does not include a private right of action, but financial institutions are required to give consumer notice, and they could face liability under deceptive trade practice statutes if the notices are determined to be deceptive or inaccurate. Furthermore, financial institutions that fail to comply with GLBA may also be subject to penalties under the Financial Institution Reform Recovery and Enforcement Act (FIRREA). FIRREA contains and offers penalties that range from up to $5,500 for violations of laws and regulations; up to $27,500 if violations are unsafe, unsound, or reckless; and up to $1.1 million for knowing violations. Given the consequences of noncompliance, organizations need to take the appropriate actions to obtain consumer protection and compliance with GLBA.

64.3.3 Consumers and Customers.

One common misconception of GLBA is the interpretation of the legislation as it relates to the nonconsumer customers of financial institutions. This is likely to occur since the term “consumer” and “customer” are oten used interchangeably. However, in the context of GLBA, the critical distinction must be made. GLBA defines a consumer as “an individual who obtains, from a financial institution, financial products or services which are to be used primarily for personal, family, or household purposes, and also means the legal representative of such an individual.” A customer is a type of consumer who has established some sort of ongoing relationship with an institution accountable to GLBA. An example of a customer would be an individual who has received credit financing to purchase a car. This individual would need to make monthly payments to a financial institution and hence has established an ongoing relationship. Under this definition, a business could not be defined either as a customer or as a consumer (since a business is not an individual) and therefore does not fall under the protections of GLBA.

64.3.4 Compliance.

Compliance with GLBA signifies that financial institutions must comply with a number of the act's provisions. From a high-level perspective, organizations must adhere to these points when seeking compliance with GLBA:

- Organizations must provide consumers with clear and conspicuous notice of the financial institution's information-sharing policies and practices.

- This notice must be given at the start of a new customer relationship and maintained on an annual basis.

- Organizations must provide customers with the right to opt out of having their nonpublic personal information shared with nonaffiliated third parties (unless the activity falls under one of the GLBA exceptions).

- They must refrain from disclosing to any nonaffiliated third-party marketer, other than a consumer reporting agency, an account number or similar form of access code to a consumer's credit card, deposit, or transaction account.

- Financial institutions must comply with the regulatory standards established to protect the security and confidentiality of customer records

- Financial institutions must also protect against security threats and unauthorized access to such protected customer information.

64.3.5 Privacy Notices.

As a part of GLBA, financial institutions are required to disseminate privacy notices to their consumers explaining what information the financial institution will collect about the consumer, whom the information may be shared with, and how the financial institution protects that information. The information the notice must refer to is the consumer's nonpublic personal information (such as a Social Security number, bank account number, or credit card number) collected, for example, during an application for auto financing. In an effort to help companies comply with this requirement in a consistent and effective manner, the Federal Trade Commission (in conjunction with various other financial regulators) established a GLBA privacy notice standard. Under this standard, financial institutions must provide a privacy notice at the inception of a relationship with a consumer and once a year for as long as the relationship persists. Furthermore, this notice must provide consumers with the option to declare within 30 days after the receipt of the notice that they do not want their information shared with the third parties mentioned in that privacy notice. Financial institutions must also mandate that the privacy notice itself be written in such a way that it is a clear and accurate statement of the company's privacy practices. Provided these requirements are met by the financial institution's privacy notice, the institution may share consumer information with its affiliated companies.

A financial institution may also share consumer information with nonaffiliated organizations provided it has clearly disclosed what information will be provided, to whom, and how it will be protected, and provided that consumers have a method of opting out clearly described in their privacy notices. However, GLBA prohibits financial institutions from disclosing consumer account numbers to nonaffiliated companies for purposes of telemarketing, direct-mail marketing, (including through e-mail), even if the consumer has not opted out of sharing the information for marketing purposes. There will be special circumstances in which consumers will not have the option to require that their information not be shared. Some of the more common occurrences of these special circumstances are:

- When a financial institution is required to share information with an outside organization as part of fulfilling its customer obligations (e.g., data processing services)

- When a financial institution is legally required to share the information

- When the information is shared with an outside service provider that market the products or services of the financial institution

64.3.6 GLBA Safeguards Rule.

A significant component of GLBA is the GLBA Safeguards Rule. The Safeguards Rule is intended to support the privacy and protective rules within GLBA. In many organizations, it is the operational driver supporting the other components of GLBA. If the other components of GLBA are the why of the legislation, then the Safeguards Rule is the how.

GLBA contains specific requirements and safeguards that are applicable to both electronic and paper records. Management must protect records in both formats, even though the widespread use of electronic data processing makes it easy to overlook sensitive consumer information in hardcopy format because an increasing number of employees work almost exclusively with electronic representations of the data. GLBA requires financial institutions to develop, implement, and continuously manage a comprehensive information security program, which it defines as including administrative, technical, and physical safeguards to protect the security of customer information.

64.3.7 Flexibility.

GLBA covers a broad array of financial institutions, and therefore mandates that an information security program be appropriate to the size, complexity, nature, and scope of the activities of each specific financial institution. This level of flexibility offers an organization's management team the flexibility to balance consumer protection against business objectives. However, it is critical that this flexibility not be abused and that the intent of the act be addressed. Furthermore, an organization's senior leadership team must not interpret the lack of specific safeguards as an opportunity for noncompliance with GLBA, but rather as an opportunity to provide consumer protection without impeding business operations.

Flexibility aside, certain key requirements must be followed to be compliant with the Safeguards Rule. The foundational security practices include having at least one designated employee to audit systems; determine risks; and develop, implement, and manage procedures to address information security. Specifically, a financial institution must provide three levels of security:

- Administrative security. Includes program management of workforce risks, employee training, and vendor oversight

- Technical security. Includes technical controls for computer systems, networks, applications, access controls, and encryption

- Physical security. Includes safeguarding facilities, corresponding environmental protection, and disaster recovery protections

In order for financial institutions to be fully compliant with the Safeguards Rule, they need to create comprehensive internal controls for strong administrative, technical, and physical safeguards. To help guide an organization's senior leadership team toward GLBA compliance, some of the major requirements that financial institutions must keep in mind when building an organizational culture founded on consumer protection and GLBA compliance are listed next:

- Validate that consumer information is kept secure and confidential.

- Validate that consumer information is protected from likely threats to its security and integrity.

- Validate that consumer information cannot be accessed by any unauthorized entities, or accessed in a way that would result in substantial loss or in a way that would inconvenience the consumer.3

Fortunately, for many organizations, implementing the Safeguards Rule does not usually require significant structural changes to their information security program. This occurs because the principle of the Safeguards Rule requires compliance with basic information security program elements. These elements are based on best practices that should already be a part of an effective information security program.

Specifically, each financial institution must designate an employee to manage the programs safeguards. Depending on financial institution's size, culture, and organizational structure, the actual title and responsibilities of the position will vary significantly. However, at a high level, this function typically requires the identification and assessment of the organization's risk as it relates to consumer information. Furthermore, the organization's risk management must be carried out diligently, so that each relevant area of the institution's operation successfully completes a comprehensive evaluation of the effectiveness of its safeguards. In most cases, the effectiveness of the organization's safeguards can be measured by the organization's ability to manage risk successfully by designing, implementing, and managing adequate information security controls. This activity should further be supported by senior management's ability successfully to monitor and test the information risk management program on a regular basis.

Finally, it is important that the financial institution's senior leadership team proactively protect customer information, even when working with third parties. Under GLBA, financial institutions must also select the appropriate service providers to support their GLBA requirements and to enter into security-minded agreements. Simply utilizing third parties does not free financial institutions from their GLBA obligations. The organization's senior leadership team must establish agreements in a manner that adequately protects consumer information and that requires the service provider to implement appropriate and GLBA relevant safeguards. GLBA stresses that, at a minimum, the safeguards performed by the third party must be equal to the protections offered internally by the financial institution's senior leadership team.

64.4 EXAMINATION PROCEDURES TO EVALUATE COMPLIANCE WITH GUIDELINES FOR SAFEGUARDING CUSTOMER INFORMATION.

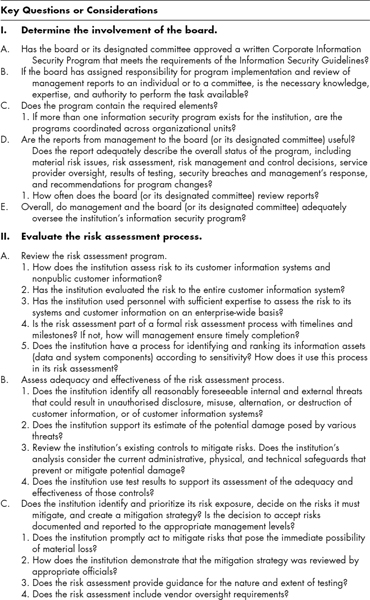

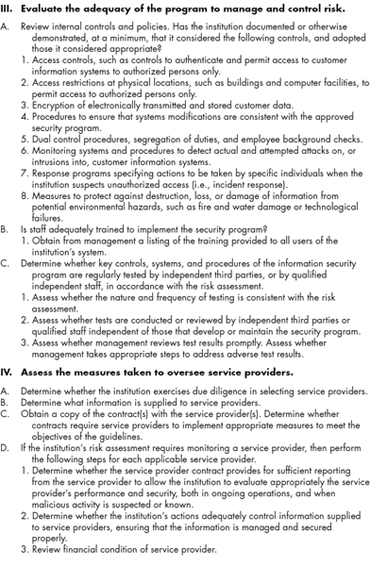

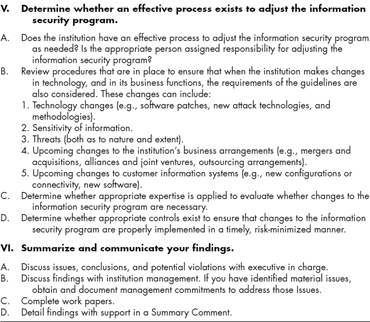

The Office of the Controller of the Currency of the United States Department of the Treasury has published a useful table of recommended evaluation procedures that will help readers apply the principles discussed in this chapter.4 A simplified and edited representation of the procedures is supplied in Exhibit 64.2.

64.5 CONCLUDING REMARKS.

The U.S. legal and regulatory security issues facing today's businesses are best exemplified by the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 and the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act. The significant increase of today's regulatory-driven business environment mandates that an organization's senior leadership team take a proactive role in compliance. This involvement must be approached from both a strategic (“tone at the top”) and operational (designing, implementing, and managing information security controls that enable enterprise level regulatory compliance) perspective.

EXHIBIT 64.2 Recommended Evaluation Procedures

Although many of today's existing regulatory requirements are very comprehensive and have a significant impact on many business environments, organizations will likely face challenges related to both existing and forthcoming regulatory requirements on a continual basis. Additionally, new regulatory requirements will be enacted to address any issues that develop from emerging technologies. Although the extent and specific requirements the future will bring are difficult to pinpoint, it is likely that regulatory requirements will continue to grow. The specific requirements will present themselves in the future, but the overall intent of the regulations will be to continue to address any emerging issues and protect consumers, shareholders, and data from abuse.

Regardless of what the future brings, an organization's senior leadership team must adequately address regulatory requirements in order to protect the interests of both their customers and their company. Organizations that take a strategic enterprise-wide governance approach, have senior management actively involved, and create a compliance-driven culture will position themselves for successful regulatory compliance.

64.6 FURTHER READING

Anand, S. Essentials of Sarbanes-Oxley. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2007

Bianco, K. M., J. Hamilton, K. R. Benson, A. A. Turner, and J. M. Pachkowski. Financial Services Modernization: Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act of 1999 Law and Explanation. Washington, DC: CCH Inc., 1999.

Cohen, H. R., and W. J. Sweet. After the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act: A Road Map for Banks, Securities Firms, and Investment Managers. New York: Practising Law Institute, 2000.

Dunham, W. B. After the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act: A Road Map for Insurance Companies. New York: Practising Law Institute, 2000.

GeoTrust. “Meeting SOX and GLBA Compliance: A Guide to Automating User Authentication and Document Integrity.” White paper, 2006, www.geotrust.com/resources/white_papers/pdfs/WP_SOX_0206s.pdf.

Greene, E. F., D. M. Becker, and L. N. Silverman. Sarbanes-Oxley Act: Analysis and Practice. New York: Aspen Law & Business, 2003.

Hermann, D. S. Complete Guide to Security and Privacy Metrics: Measuring Regulatory Compliance, Operational Resilience, and ROI. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press, 2006.

Miles, B. L. The Canadian Financial System. Huntington, NY: Nova Science Publishers, 2004.

64.7 NOTES

1. American Institute of Certified Public Accountants Center for Audit Quality, AICPA Sarbanes-Oxley Home Page, 2008, http://thecaq.aicpa.org/Resources/Sarbanes+Oxley/.

2. Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act: 15 U.S.C. SubChapter 1, §§ 6801–6809, www.ftc.gov/privacy/glbact/glbsub1.htm.

3. Federal Trade Commission, “Standards for Safeguarding Customer Information: Final Rule,” May 23, 2002, 16 CFR § 314 ¶1a, www.ftc.gov/os/2002/05/67fr36585.pdf.

4. U.S. Department of the Treasury, Office of the Controller of the Currency, “GLBA Examination Procedures,” 2001, www.occ.treas.gov/ftp/bulletin/2001-35a.pdf.