CHAPTER 75

UNDERGRADUATE AND GRADUATE EDUCATION IN INFORMATION ASSURANCE

Vic Maconachy and Seymour Bosworth

75.2 U.S. INITIATIVES IN TRAINING AND EDUCATION OF INFORMATION

75.2.2 Growth of IA Education Programs in the United States

75.2.3 Information Assurance as Part of a Learning Continuum

75.3 DISTANCE LEARNING IN HIGHER EDUCATION

75.4 BUSINESS CONTINUITY MANAGEMENT

75.1 INTRODUCTION.

Information assurance has come to the forefront of the consciousness of the modern world. Recent events such as high-publicity breaches of security, as well as pervasive small-scale abuses of the technologies available at work and at home, have highlighted the need for trained professionals able to operate in the complex world of information assurance. Toward this end, recent initiatives in the United States and Europe have added information assurance into the undergraduate and graduate curriculum of more common degrees such as computer science, and have also identified information assurance as its own discipline worthy of its own curriculum. This chapter outlines some of the initiatives that have taken place in the United States and speculates about the future of the discipline.

75.2 U.S. INITIATIVES IN TRAINING AND EDUCATION OF INFORMATION ASSURANCE

75.2.1 TIE System.

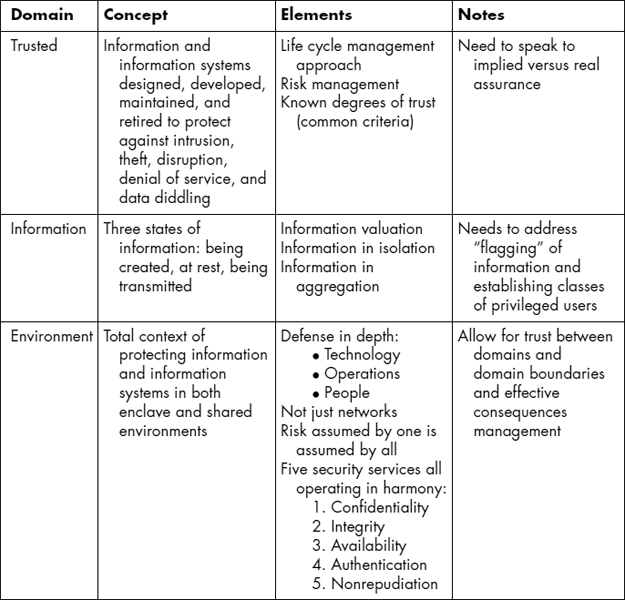

Any approach to information assurance (IA) education must be presented in a conceptual context. The Trusted Information Environment (TIE) model shown in Exhibit 75.1 is a view of protecting information and information systems within the context of a trusted cyberspace.

EXHIBIT 75.1 Approach to TIE Together Information and Information Systems Security

While some refer to this approach as an enclave mentality, it does open the possibilities for secure cross-domain solutions (CDS). In the CDS environment, permissions are granted and revoked as access to shared information and information system space is allocated and adjudicated by the system owners. This will be the way of the future as more segments of our society desire to intercommunicate. Examples of this might be insurance companies gaining, or being granted access to, selected patient information.

In the TIE approach, educators can see two things immediately:

- Understanding (and thus learning) of IA is surrounded by many interacting factors.

- In the Environmental area, people development is a critical part of defense in depth.

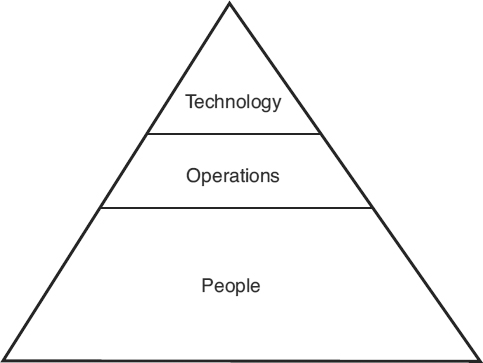

The term “defense in depth” (DID) refers not just to a program or system, but to a way of thinking about information assurance. In this view, there are only three real broad classes of countermeasures in any information assurance arsenal, as shown in Exhibit 75.2.

EXHIBIT 75.2 Three Fundamental Countermeasures to Protect Critical Information Infrastructures

- The first countermeasure, technology, often comes to market with flaws.

- The second countermeasure, operations, encompasses things such as best practices, policy, and so on. This countermeasure is necessary because of the flaws in the first countermeasure.

- The third countermeasure, people, includes not just the education and training but also the development of people. The development takes many forms, running the gamut from seminars through personal certifications and career development. The people part of the countermeasures triad serves as the base or foundation for the other two countermeasures.

Intrinsic in this, or any IA model, is the concept of risk. In a trusted environment, risk assumed by one is assumed by all. Here, education has an important, fundamental, and critical role to play. A common understanding of risk (to include threat and vulnerability) among users, operators, maintainers, and designers of information systems can make the difference between a secure and an inherently insecure system. Thus, a risk-based approach to teaching information assurance lies at the very heart of preparing IA professionals.

The people part of an IA program is not just about education. It is about development of people for the IA profession. That development includes a full spectrum of learning and proficiency development. The learning portion includes a range of understanding from simple awareness (often referred to as situational awareness) through formal education. The proficiency part is the testing and formal credentialing that certain knowledge and skills have been mastered. The latter part of this equation has given rise to an entire suite of private sector certifications such as CISSP,1 GIAC,2 Security Plus,3 and other commercial certification programs discussed in Chapter 74 in this Handbook. Some authors contend that certifications amount to “inferred professionalization” in the sense that certifications focus exclusively on easy-to-measure indicators of proficiency.4 Those authors would argue that in contrast, conferred professionalization would assure an individual is not just competent but actually fully equipped to practice a discipline. In the conferred professionalization model, the individual is judged to be ready by recognized practitioners in that field. Most important, as Mike Whitman put it, “Policy must be communicated to employees. In addition, new technology often requires training. Training, Awareness and Education are essential if employees are to exhibit safe and controlled behavior.”5 The National Centers of Academic Excellence in Information Assurance Education serve as an excellent starting point to seek personal and employee education in IA.6

75.2.2 Growth of IA Education Programs in the United States.

In 2004, Drs. Matt Bishop and Deborah Frinke characterized the state of IA education: “Security and privacy education is, at its heart, driven by a compelling national and international need.”7 In the past several years, the study and research of information assurance has risen from an area of study of limited interest to an international rush for developing courses and research. In February 2003, the President of the United States reported

In addition to the vulnerabilities in existing information technology systems, there are at least two other major barriers to users and managers acting to improve cybersecurity: (1) a lack of familiarity, knowledge and understanding of the issues, and (2) an inability to find sufficient numbers of adequately trained and/or appropriately certified personnel to create and manage secure systems.8

As part of a response to this need, the National Security Agency, in cooperation with the Department of Homeland Security, established national Centers of Academic Excellence in Information Assurance Education (CAE).9 This program fosters the development and identification of universities that have reached a significant level of depth and maturity in building IA curriculum, and looks beyond curriculum to assess the long-term commitment of universities to IA education. The purpose and vision of the National CAE program is: “Reducing the vulnerability of our National Information Infrastructure by promoting higher education in information assurance and producing a growing number of professionals with IA expertise in various disciplines.” This government-sponsored program does not attempt to accredit academic institutions that teach IA. Rather, the program stands as a way to recognize and encourage the study of IA. There are 10 multipart criteria for the program, which include such things as having faculty active in IA practice and research as well as declared concentrations in IA. At the time of writing (June 2008), only 93 universities have been formally recognized as CAEs.10

An interesting finding, after several years of the CAE program, is the documentation that the study of IA is truly interdisciplinary. Subjects in IA range from telecommunications through computer science and into policy and legal areas. The fact that the IA concentrations can be found in several disciplines gives further evidence to the pervasive nature of IA. IA programs are found in electrical engineering programs, computer science programs, business programs, and information technology programs. The growth in the recognition of IA as part of many career fields now finds elements of IA taught in medical schools, law schools, and, perhaps most important, schools of education, where teachers learn the importance of protecting students from the harm often found on the Internet.

The curricula at the CAEs are based on national education and training standards developed by the Committee for National Security Systems (CNSS).11 Prior to those standards, there was neither research nor a generally accepted codified body of knowledge in the IA community. The CNSS standards were developed with the assumption that U.S. employers need IA professionals grounded in theory and principles and also able to implement changes. The standards serve to codify what IA knowledge, skills, and abilities (KSAs) IA professionals should know and what levels of performance they should be expected to exhibit.

The CNSS Training Standards are generally regarded as training road maps. However, at the higher cognitive levels of operation, those standards offer clear guidance to educators doing curriculum design. Using the Bloom Taxonomy of Learning,12 one can see that the CNSS Standards cover the developmental range from awareness through literacy and training into education. For example, the CNSSI Instruction # 4016 includes the “Countermeasures IA functions” and “Analyzing Potential Countermeasures.” In that section, these levels of performance are defined:

- Entry level: Discuss testing roles and responsibilities.

- Intermediate level: Apply discriminate approach variables and constants based on test procedures to gain acceptance for joint systems usage.

- Advanced level: Analyze applicability of network and vulnerability scanning tools.13

Note the increasing complexity of the requirements. Initial requirements are simply a broad understanding of IA countermeasures. At the advanced level, the student must put IA countermeasures into the context of network vulnerability scanning. This natural progression in difficulty helps us distinguish programs that provide awareness from those that are more training-oriented and from education-focused curricula. The need for the distinction among awareness, training, and education in IA was first recognized in 1989.14 The debate at that time centered around compliance with the Computer Security Act of 1987 (PL 100-235), which required annual training in computer security “for all persons involved in management, use, or operation of Federal computer systems that contain sensitive information.”15 This delineation of levels also lends itself to developing career progression from entry level through journeyman to master.

75.2.3 Information Assurance as Part of a Learning Continuum.

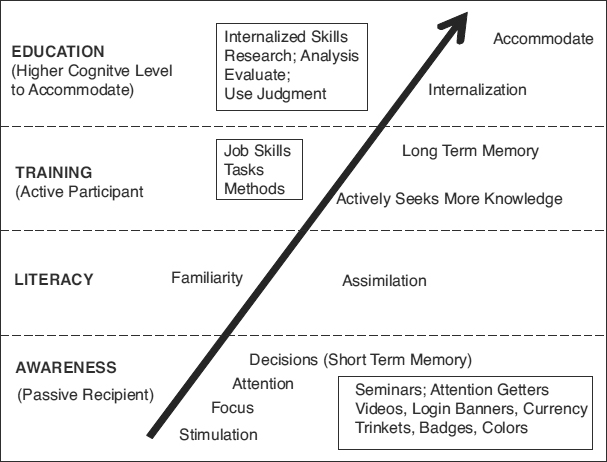

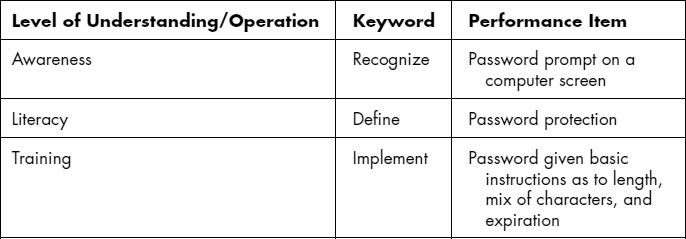

The translation of ascending knowledge and skills can best be depicted by the Information Assurance Awareness, Literacy, Training, and Education Continuum as shown in Exhibit 75.3.16 As a person becomes aware of information assurance (IA) and then becomes engaged with active learning about IA, he or she may well proceed through a continuum of ever-increasing complex knowledge. A classic example of this progression is illustrated using passwords as a topical area as shown in Exhibit 75.4.

As shown in Exhibit 75.4, using passwords progresses from recognizing a prompt to conducting evaluations by designers of password strength schema. When IA knowledge and skills are analyzed to this level, one can quickly see the difference between requirements for end users versus system administrators versus design engineers. The CNSS standards include a hierarchy of verbs used to discern differing levels of IA performance and complexity of understanding:

EXHIBIT 75.3 IA Awareness, Literacy, Training, and Education Continuum

EXHIBIT 75.4 Maturation of Password Handling

Entry-Level Verbs:

- Define

- Demonstrate

- Describe

- Identify

- Outline

- Use

Intermediate-Level Verbs:

Advanced-Level Verbs:

- Compare

- Evaluate

- Integrate

- Resolve

- Revise

- Verify

There are currently six CNSS Education and Training Standards. They are:

- Information systems security professionals

- Senior systems managers

- System administrators

- Information systems security officers

- System certifiers

- Risk analyst

Current plans call for the development of standards for information systems security engineers and end users. An area that is receiving considerable attention is the codification of best practices and required knowledge for personnel developing code. This area could be termed secure coding or software assurance, as discussed in Chapters 38 and 39 in this Handbook. These competencies should be taught to all those who do or practice coding. Developing a cadre of secure coding experts may not affect industry practices in this area as fast as teaching larger numbers of coders. In essence, security must become an essential core knowledge and competency for all coders.

An example of the information security training roles of various information technology workers can also be found in NIST Special Publication 800-16.17 In that document, it is stressed that IT security training needs evolve or change over time. More important, the NIST publication recognizes the fact that information assurance is not the job only for IA professionals. Requirements for knowledge and skills in IA pervade the federal work environment. From the first-line supervisor to the local system administrator, IA skills are now minimal essential skills required to sustain the federal information networks and architectures. A more recent NIST publication18 notes that, within the U.S. federal government, there is a mandate for IT security training. Specifically, the Federal Information Security Management Act (FISMA) of 2002 tasks the head of each agency with the responsibility to “ensure that the agency has trained personnel sufficient to assist the agency in complying with (the requirements) and related policies, procedures, standards, and guidelines.” Thus, within the U.S. Government, there is a mandate to employee IA professionals in support of secure information technology operations.

The requirement for trained and educated IA professionals extends beyond the government sector and has been recognized as a need for many years. Steele19 noted that 65 percent of hospitals with links to external computer systems did not have adequate security measures and 80 percent had not properly defined who should have access to computer records.” This condition probably extends into many other critical information infrastructures, such as transportation and water systems. A simplistic yet elegant paradigm for understanding the relationship between the states of information and various countermeasures can be found in Exhibit 75.5. In this model, understanding that security countermeasures must include a people dimension is critical to preserving and defending information systems.20

EXHIBIT 75.5 Information Assurance Model

In a later article, further refining this approach, additional dimensions were added: An IA professional must also integrate the concepts of time and social context into this paradigm. “Time, when integrated into this model is not a causal agent of change, but a confounding change agent.”21 Further, as we have learned from recent physical calamities, the state of IA may be seriously affected by the social context of our times. For instance, after September 11, 2001, some U.S. Government homeland security initiatives were based on the assumption that citizens would willingly give up some personal and constitutionally guaranteed freedoms in return for measures described as leading to a more secure environment. In some nations, strong cryptography is forbidden on their telecommunications systems; similarly, Internet service providers in some areas of the world are expected to provide names of individuals who frequent certain Web sites.22 All of these elements combine to present an ever-shifting international social climate for information assurance.

75.2.4 Time to Respond.

In the words of U.S. Senator John Edwards when he introduced the Cybersecurity Research and Education Act of 2002: “We now live in a world where terrorists can do as much damage with a keyboard and a modem as with a gun or bomb…. Two choices are available: adapt before the attack or afterward.”

Adaptation of a society begins with education and is born out of experience. Cyber-security awareness, training, and education are the key to a safer cyberworld. This education must begin at early ages in order for cyber-security to become a part of every person's safe computing practices. Programs such as Stay Safe On-Line offer promise in reaching and preaching safe and ethical cyberbehavior.23 Programs such as the National Information Assurance Training and Education Center at Idaho State University offer an amazing range of curriculum materials suitable for all levels of IA education.24

75.3 DISTANCE LEARNING IN HIGHER EDUCATION

Distance learning, or e-learning, whose most important element is the online course, provides a relatively new facility for education in Information Assurance and related subjects. A typical institutional set of principles, as stated by the American Distance Education Consortium, (ADEC), requires that “Distance learning programs should result in learning outcomes appropriate to the rigor and breadth of the degree/certificate awarded. Programs should be coherent, comprehensive, and developed with appropriate discipline and pedagogical rationale. Each program should provide for significant interaction, whether real-time or delayed interaction, between faculty and students and among students.”25

To accomplish this, a superior mix of media, students, teachers, providers, and courses is necessary for both distance learning and distance teaching.

75.3.1 Media

In distance learning, the central medium for communications between teacher and students is usually a computer on the Internet, rather than face-to-face interactions. Other media include:

- Cassettes: audio or video, at home or in groups

- Computers: online or offline

- Conversations: e-mail, Instant Messaging, face-to-face, phone

- Disks: CD or DVD

- Distribution: hand-outs, USPS, delivery services, computers

- Electronic whiteboards and blackboards

- Fax: text, graphics

- Group Sessions: demonstrations, lectures, experiments

- Hand-helds: IP based, MP3, PDA

- Internet: text, graphics, VoIP

- Presentations: slides, movies, VCRs

- Print: textbooks, reports, surveys, workbooks, study guides

- Teleconferences: audio, video

- Wireless Communications: television, compressed video, radio

Unlike conventional classrooms, where communication between teacher and student are instantaneous and coordinated, in distance learning there may be large and random intervals between a statement or question and the response. Such media, and their methodologies, are often termed asynchronous.

75.3.2 Students

The importance of online learning is exemplified by the finding that almost 3.5 million students were taking at least one online course during the fall of 2006, and that nearly twenty percent of all U.S. higher education students were taking at least one online course. This represented a 9.7% annual growth rate over four years as compared with the overall higher education student population.26

The major advantages of distance learning from the students' point of view lie in overcoming the barrier imposed by conventional on-campus studies. Some of the obstacles that are likely to be overcome are scheduling or time constraints, inconvenient locations, disabilities, costs, and family and business commitments. The flexibility and innate characteristics of distance learning can lower or eliminate these barriers.

In a more positive sense, one of the advantages lies in integrating the Web as a convenient, easily accessed source of information. Another is the ability to organize thoughts before responding to a query. Threaded discussions provide a means for exploring a subject in detail, and over extended periods of time. One student commented:

In a face-to-face class the instructor initiates the action; meeting the class, handing out the syllabus, etc. In online instruction, the student initiates the action by going to the Web, posting a message, or doing something. Also, I think that students and instructors communicate on a more equal footing where all of the power dynamics of the traditional face-to-face classroom are absent.27

To a teacher, of course, that may not represent an advantage.

75.3.3 Teachers

From a teacher's viewpoint, many of the advantages that accrue to students may also benefit themselves. However, there are some difficulties to be overcome. From start to finish, a high degree of motivation must be maintained despite some or all of these disincentives.

- Old lecture skills may have to be discarded

- New multi-media presentation skills will have to be learned

- The teacher may cease to be the main font of wisdom, but only a pointer to where it resides

- Some technical skills will be required to operate new equipment, or to work with equipment operators

- More preparation time will be needed

- Students must be motivated, self-disciplined, and encouraged to participate

- Excessive use of e-mail may have to be restrained

- Course material provided online loses proprietary value, and makes replacement of the originator easier, even by low-paid, unskilled presenters

- Teaching conventional courses may be more higher regarded by administrators when deciding on tenure or promotions

In spite of these, and other problems, an increasing number of teachers find distance learning to be a rewarding application for their knowledge and skills.

75.3.4 Providers

Why do institutions provide online offerings? Improving student access is the most often cited objective for online courses and programs. All types of institutions cite improved student access as their top reason for offering online courses and programs.

- Institutions that are the most engaged in online education cite increasing the rate of degree completion as a very important objective.

- Online is not seen as a way to lower costs; reduced or contained costs are among the least-cited objectives for online education.

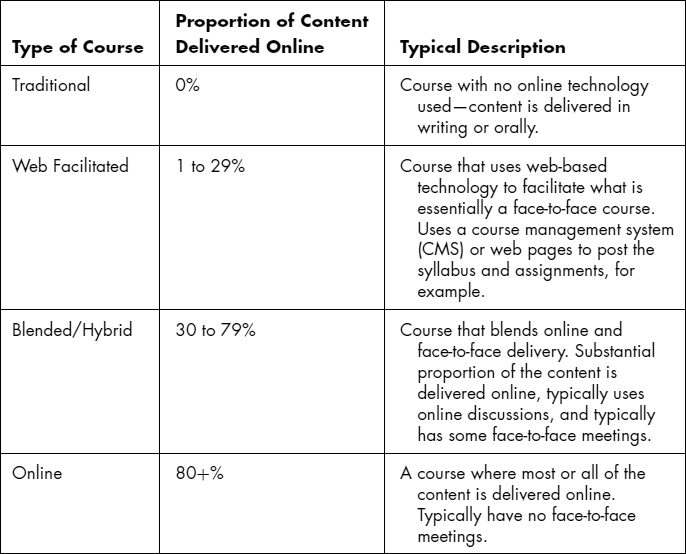

EXHIBIT 75.6 Type of Course

The appeal of online instruction is indicated by the high number of institutions which cite growth in continuing and/or professional education as an objective for their online offerings.28

75.3.5 Courses

The range of institutions providing online courses extends from the U.S. government to the most prestigious private universities, and from giant State universities to small, independent colleges. Even private, for-profit organizations have offerings in the field.

There are courses available online that offer baccalaureate, graduate, and postgraduate degree credits, along with others that provide associate degrees, or certificates. The courses may be grouped into several types as defined by the Sloan Consortium.29

75.3.6 Summary

Online learning is both widespread and rapidly proliferating. In higher education, it may well be the wave of the future because of its many advantages, and in spite of its significant problems. The present number of institutions is large and diverse, as are the courses available in information assurance and related subjects. Substantial growth in students, faculty, institutions, courses, and technology warrant substantial investments of time, money, and other resources in all aspects of this mushrooming phenomenon. Anyone seeking to advance a career, either as a student or as a teacher, but unable or unwilling to attend full-time classes, would benefit from distance and online educational opportunities.

75.4 BUSINESS CONTINUITY MANAGEMENT.

Events such as the bombings of 9/11 and Hurricane Katrina have brought business continuity management (BCM) into mainstream corporate practice. Businesses that had plans for continuity of service to customers during a business disruption survived those events, whereas those without plans often failed. As a result, organizations both large and small are implementing BCM systems. Once relegated to the margins of corporate practice as an aspect of information technology or corporate security, BCM has become recognized as a fundamental aspect of sound business practice.

The growth of continuity management has been further fueled by regulations requiring continuity programs in industries such as healthcare and finance. Insurance companies are also starting to require continuity programs as a condition of coverage. Moreover, with 85 percent of the nation's critical infrastructure, and nearly 100 percent of the economic infrastructure, in private hands, BCM is a national security priority. Recognizing the importance of securing the nation's economic infrastructure for national security, President Clinton issued Presidential Decision Directive Order 63 in 1997 to address critical infrastructure protection.30 The federal government has extended this effort to support private-sector BCM programs. In August 2007, the federal government passed Implementing Recommendations of the 9/11 Commission Act of 2007, which mandates the Department of Homeland Security to actively encourage the development of continuity programs in the United States.31

Continuity of operations is as much needed in the public sphere as the private, as public sector agencies must have programs to ensure their own continuity of service during an emergency. In recognition of the public sector need for continuity programs, President Bush signed National Security and Homeland Security Presidential Directive 51, requiring continuity programs to “be incorporated into daily operations of all executive departments and agencies.”32

The growth in BCM programs has fueled tremendous demand for professionals who understand risk management in the context of business operations. As a result, the number of business continuity professionals has exploded in recent years. CNN recently named Business Continuity Director one of the “Seven Trendy New Jobs,” and membership in professional organizations in the field is growing rapidly.33

Norwich University in Northfield, Vermont, developed an online Master of Science in Business Continuity Management degree in 2008 to serve the education needs of private and public sector business continuity professionals.34 We expect to see increased attention to this discipline at both undergraduate and graduate levels of education.35

75.5 CONCLUDING REMARKS.

Information assurance, with public and private sector development of educational and training initiatives, has secured a required focus of study for future employees. It is a constantly changing field, wide open for continued new research. The governmental support and mandate of such initiatives will ensure that if any companies or universities were to lag in their adoption, there would be unfavorable consequences, aside from the presence of a serious shortcoming in their educational curriculum.

We can expect to see continued growth in information assurance education in colleges and universities worldwide.

75.6 NOTES

3. www.quickcert.com/security+.htm.

4. W. V. Maconachy, L. Figallo, and C. D. Schou, “INFOSEC Professionalization: A Road to be Traveled,” Forum for Advancing Software Engineering Education 9, No. 1 (January 1999); www.cs.ttu.edu/fase/v9n01.txt.

5. Michael E. Whitman and Herbert J. Mattord, Principles of Information Security, 2nd ed. (Boston: Thompson Course Technology, 2005), p. 139.

6. www.nsa.gov/ia/academia/acade00001.cfm.

7. Matt Bishop and Deborah Frinke, “Joining the Security Education Community,” IEEE Computer Security, 2004.

8. G. W. Bush “The National Strategy to Secure Cyberspace,” The White House (2003); www.whitehouse.gov/pcipb/.

9. www.nsa.gov/ia/academia/acade00001.cfm

10. www.nsa.gov/ia/academia/caeiae.cfm.

11. www.nsa.gov/ia/academia/cnss.standards.cfm

12. www.officeport.com/edu/blooms.htm

13. Committee for National Security Systems Instruction No. 4016, National Information Assurance Training and Education Standard for Risk Analyst, Washington, DC, November 2005.

14. W. V. Maconachy, “Computer Security Education, Training and Awareness: Turning a Philosophical Orientation into Practical Reality,” Proceedings: 12th National Computer Security Conference, p. 557A-I, National Computer Security Center (October 1989).

15. Computer Security Act of 1987, http://csrc.nist.gov/groups/SMA/ispab/documents/csa_87.txt.

16. W. V.Maconachy, Corey D.Schou, Daniel Ragsdale, and Don Welch. “A Model for Information Assurance: An Integrated Approach,” Proceedings of the 2001 IEEE Workshop on Information Assurance Security, United States Military Academy, West Point, NY, June 5–6, 2001.

17. National Institute of Standards and Technology. Information Technology Security Training Requirements: A Role and Performance-Based Model, SP 800-16 (April 1998); http://csrc.nist.gov/publications/nistpubs/800-16/800-16.pdf.

18. National Institute of Standards and Technology. Building an Information Technology Security Awareness and Training Program, SP 800-50 (October 2003); http://csrc.nist.gov/publications/nistpubs/800-50/NIST-SP800-50.pdf.

19. H. Steele, “The Prevention of Non-consensual Access to Confidential Health Care Information in Cyberspace,” Computer Law Review, Technology Journal (Spring 1997)

20. C. Schou, J. Frost, and W. V. Maconachy, “Information Assurance in Biomedical Informatics Systems. The Role of Literacy, Awareness, Training and Education in Protecting Healthcare's Critical Information Infrastructure,” IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Magazine (January 2004).

21. A Model for Information Assurance: An Integrated Approach. Proceedings, 2nd Annual IEEE Systems, Man and Cybernetics Information Assurance Workshop. West Point, June 2001.

22. See, for example, Associated Press, “House OKs Warrantless Wiretapping Bill: Senate is Also Expected to Approve Measure Providing Protection for Telecoms,” CBS News, June 25, 2008; www.cbsnews.com/stories/2008/06/20/national/main4198400.shtml.

25. American Distance Education Consortium. www.adec.edu/admin/papers/GPforDL.html.

26. Allen, I. E. and Seaman, J, Online Nation: Five Years of Growth in Online Learning, Needham, MA: Sloan-C, 2007. www.sloan-C.org/publications/survey/index.asp.

27. Teaching College Courses Online vs Face-to-Face. www.thejournal.com/articles/15358_4.

28. Allen, I. E. and Seaman, J, Online Nation.

29. Allen, I. E. and Seaman, J, Online Nation.

30. W. J. Clinton, Presidential Decision Directive/NSC-63: Critical Infrastructure Protection (1998), http://fas.org/irp/offdocs/pdd/pdd-63.htm.

31. H. R. 1: Implementing Recommendations of the 9/11 Commission Act of 2007, www.govtrack.us/congress/bill.xpd?bill=h110-1.

32. G. W. Bush, National Security Presidential Directive 51, Homeland Security Presidential Directive/HSPD-20: National Continuity Policy (2007), www.whitehouse.gov/news/releases/2007/05/20070509-12.html.

33. J. Sahadi, “7 Trendy New Jobs: From Keeping BlackBerrys in Shape to Settling Minor Divorce Disputes, Some Interesting New Positions Have Sprung Up in Recent Years,” CNNMoney.com, April 21, 2006; http://money.cnn.com/2006/04/20/pf/new_jobs/index.htm.

34. See www.graduate.norwich.edu/business-continuity/.

35. This section was contributed by John Orlando.