CHAPTER 49

IMPLEMENTING A SECURITY AWARENESS PROGRAM

K. Rudolph

49.2 AWARENESS AS A SURVIVAL TECHNIQUE

49.2.1 Awareness versus Training

49.2.2 IT Security Is a People Problem

49.2.3 Overnight Success Takes Time

49.3.1 In-Place Information Security Policy

49.3.2 Senior-Level Management Support

49.3.6 Reward for Good Security Behaviors

49.3.7 Destination and Road Maps

49.3.8 Visibility and Audience Appeal

49.4 OBSTACLES AND OPPORTUNITIES

49.4.1 Gaining Management Support

49.4.2 Keep Management Informed

49.4.5 Overcoming Audience Resistance

49.4.6 Addressing the Diffusion of Responsibility

49.5.1 Awareness as Social Marketing

49.6.1 What Do Security Incidents Look Like?

49.6.2 What Do I Do about Security?

49.6.3 Basic Security Concepts

49.7 TECHNIQUES AND PRINCIPLES

49.7.1 Start with a Bang: Make It Attention Getting and Memorable

49.7.2 Appeal to the Target Audience

49.7.3 Address Personality and Learning Styles

49.7.4 Keep It Simple: Awareness Is Not Training

49.7.5 Use Logos, Themes, and Images

49.7.6 Use Stories and Examples: Current and Credible

49.7.8 Involve the Audience: Buy-In Is Better than Coercion

49.7.11 Incorporate User Acknowledgment and Sign-Off

49.8.4 Checklists, Pamphlets, Tip Sheets

49.8.5 Memos from Top Management

49.8.7 In-Person Briefings (and Brown-Bag Lunches)

49.8.9 Intranet and/or Internet

49.8.11 Awareness Coupons and Memo Pads

49.8.13 Trinkets and Give-Aways

49.8.15 Sign-On Screen Messages

49.8.16 Surveys and Suggestion Programs

49.8.17 Inspections and Audits

49.8.18 Events, Conferences, Briefings, and Presentations

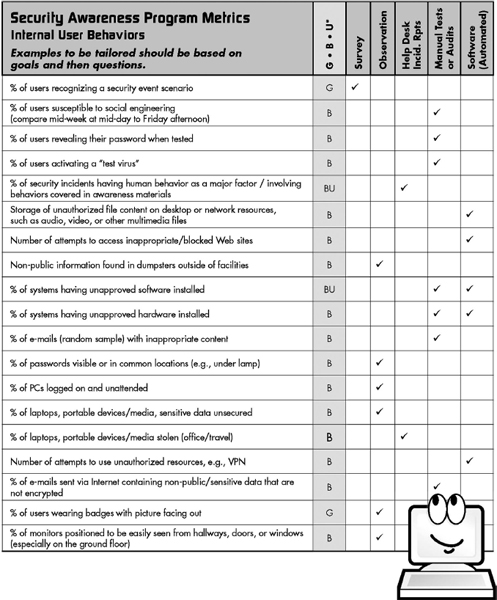

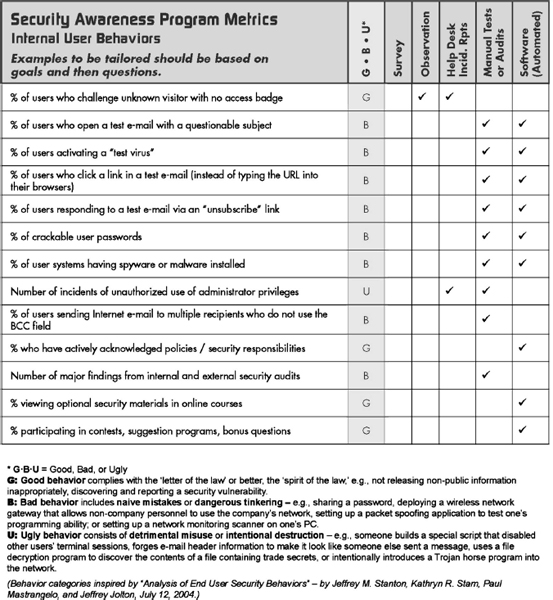

49.9 MEASUREMENT AND EVALUATION

49.9.4 Learning or Teaching Effectiveness

49.1 INTRODUCTION.

Even the best security process will fail when implemented by the uninformed. Information technology security awareness is achieved when people know what is going on around them, can recognize potential security violations or suspicious circumstances, and know what initial actions to take. Security awareness is the result of activities, tools, and techniques intended to attract people's attention and to help them focus on security. Because people play an integral role in protecting an organization's assets, security awareness among staff, contractors, partners, and customers is a necessary and cost-effective countermeasure against security breaches. Effective awareness programs motivate people and provide measurable benefits. Prerequisites for implementing a security awareness program successfully include senior-level management support, an in-place security policy, measurable goals, and a plan for reaching those goals. Attention-getting awareness materials tailored to the audience and to the technology yield maximum program impact. This chapter contains practical information on design approaches for an awareness program, including its content, techniques, principles, tools, measurement approaches, and evaluation techniques.

49.2 AWARENESS AS A SURVIVAL TECHNIQUE.

In recent years, awareness of security concerns worldwide has increased. Business, government organizations, and individuals are conducting a significant part of their activities electronically. Electronic information (corporate and personal data) often can be easily accessed, copied, and distributed. Increased use of information technology (IT) and the Internet has resulted in increased risks and increased regulatory requirements. Public awareness of the risks of inappropriate, unwanted, or illegal access, use, and disclosure of data has also increased. Security, once perceived as the responsibility of the IT department, is now an issue at the board of directors' level.

More, more advanced, and more connected digital technologies have brought new threats and vulnerabilities. An insider or visitor could take away entire databases concealed in a pocket on a thumb drive. As of early 2008, these small, portable memory devices can hold up to 100 GB in a configuration the size of a business card.1 Professional hackers are now being commissioned for specific security attacks. The following are some of the trends that are growing in popularity with criminals: malicious code, phishing, blended attacks, search engine poisoning, exploitation of application systems vulnerabilities, mobile device viruses, and target-specific attacks.

Changes in mobile devices, wireless networks, and cybercrime methods mean that the success or even survival of an organization may depend on personnel understanding and following the requirements for protecting information assets.

Security awareness is the individual's understanding that security is important and that everyone has a role in ensuring the security of information and information technology. The two questions at the heart of a security awareness program are:

- Would the individual recognize a potential security problem?

- Would that person take appropriate action?

In the animal kingdom, awareness—being alert to danger signals and responding quickly—can be the difference between survival and death. Bats and dolphins use sonar to detect and avoid dangers, while cats use whiskers and keen senses of hearing, smell, and night vision to probe their environments. Being alert to danger signals and responding quickly is also important for organizations. An organization's staff can similarly function as its detection instruments, automatically recognizing things that are out of place and reflexively taking preventive and mitigating actions. Awareness activities can build and support this reflexive behavior.

Awareness among an organization's staff (including contractors, third-party partners and vendors, and, in some cases, customers) is a cost-effective security countermeasure; that is, one that costs less than the impact that it addresses. When determining the cost effectiveness of controls, a general rule is that prevention costs less than cure. “Controls designed to prevent breaches from occurring are more cost-effective than those designed to identify and/or correct breaches after the fact—the main reason being that preventive controls reduce or eliminate the impact costs.”2 The cost of security controls can include up-front expenses (e.g., purchase price, maintenance, or license fees), implementation and management costs, and costs associated with using or operating the controls. “Cutting-edge high technology security controls are, generally speaking, substantially more expensive across all three categories than low-tech service or procedural controls.”3 Security consultant Hal Tipton calls security awareness “the most valuable yet the most overlooked and underfunded mechanism for improving the implementation of information security.”4

Members of an organization's workforce are often the first to be affected by a security incident. Their compliance with security policy can make or break a security program. A staff that is security-aware can detect and prevent many incidents and mitigate damage when incidents do occur. To reap these benefits, awareness must be a critical part of an organization's security program.

Many industries, as well as the U.S. Government, are finding that security education and awareness are no longer optional.5 In the United States, the Federal Information Security Management Act (FISMA), the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), the Sarbanes-Oxley Act (SOX), and the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act (GLBA) require the federal government, the healthcare industry, and financial institutions, respectively, to provide mandatory security awareness for staff. Various U.S. states have passed laws that supplement the federal laws. Also, the European Union follows a Data Protection Directive that addresses the access, use, and disclosure of personal information. “As this type of legislation becomes reasonable and customary, negligence and due diligence law come into play. Therefore, security awareness training is likely to become mandatory for all industries.”6

49.2.1 Awareness versus Training.

Learning is a continuum; it starts with awareness, builds to training, and evolves into education.7 Rebecca Herold, security consultant and author, explains that “[a]wareness is typically the ‘what’ component of your education strategy for influencing behavior and practice; training is typically the ‘how’ component to implement security and privacy.”8

Security awareness differs from security training in purpose, approach, and results. Awareness has the following characteristics:

- It is intended to focus attention on security and to change attitudes. Awareness sets the stage for training by changing individual perceptions and the organizational culture so that security is recognized as critical. “Awareness activities are intended to allow individuals to recognize Information Technology (IT) security concerns and respond accordingly.”9

- Learning tends to be short term, immediate, and specific.

- Learners are information recipients.

- It reaches broad audiences with multiple, attractive, attention-getting techniques.

Training exhibits different characteristics:

- It is more formal than awareness. The purpose of training is to build knowledge and skills to facilitate job performance.

- Training takes longer and involves producing skills and competency for those involved in functional specialties other than IT security (e.g., management, systems design, and acquisition).

- It is provided selectively based on an individual's roles (job functions) and needs.

- Learners have an active role.

49.2.2 IT Security Is a People Problem.

In 1952, UNIVAC, the first commercial computer, was used to predict the outcome of the U.S. presidential election. Early in the evening, based on input of the first returns, the computer predicted a landslide for Eisenhower. Walter Cronkite refused to report these results because he did not find them credible. Some people went as far as to suggest that they reprogram the computer to provide a different result. In the end, Eisenhower did win by a landslide, which led some to remark that the problem with computers is people.

IT security used to be viewed as a technology problem. Sophisticated hardware and software solutions are still used to control access, detect potential intrusions, and prevent fraud. Yet security incidents are occurring with increasing frequency. The reality is that computer security is both a human and a technological problem: People do not perform work consistently; they get tired and may perform tasks erratically; they may get angry (at the organization, their spouse, their boss, or at work in general) and intentionally try to disrupt or compromise operations; they may cause system failures by independently “improving” business processes; or they just do not follow established policies and procedures. As security author Donn B. Parker points out, some employees believe that “they can work faster and better by not making backups, using pirated software, failing to securely store sensitive information, endangering information, and secretly sharing the organization's sensitive information with competitors over the Internet in return for favors.”10 Connecting computers into networks significantly increases risk because network security depends on the cooperation of every user. A single individual who allows a desktop or laptop computer to be compromised places every interconnected system and its associated assets at risk.

“Computers alone don't implement information security policies and standards—human beings purchase and configure the systems, switch on the control functions, monitor the alarms, and run them.”11 In addition, people are more perceptive and adaptive than hardware or software components. Thus, if properly trained and motivated, they can be the strongest and most effective security countermeasure. Investments in technology to improve information security must be accompanied by investments in people. An awareness program is a needed complement to technical controls, not an alternative.

49.2.3 Overnight Success Takes Time.

Like exercise, security awareness requires time and repetition. If the audience is bombarded with the total awareness arsenal at one time, it becomes overwhelmed and rejects or fails to assimilate much of the information presented. Information overload is a common mistake in awareness programs. If the same volume of information is presented over an extended time, information retention and assimilation into daily business processes are increased.

Effective awareness programs are long-term activities that bring about gradual improvement. Management must consistently support the security program and not change approaches from year to year for the sake of change. Awareness activities must consistently reinforce the awareness message rather than replacing it with each new management interpretation. An effective security awareness program uses techniques similar to those used for a social marketing campaign, repeating a consistent message (e.g., “Don't drink and drive,” “Buckle up,” “Smoking kills,” “Loose lips sink ships”) and may need two to five years to produce measurable results.12

49.3 CRITICAL SUCCESS FACTORS.

A security awareness program needs a successful launch for maximum impact. Critical program elements include:

- An information security policy that establishes the security rules of behavior for the organization

- Senior-level management support and buy-in to demonstrate the importance of security

- Destinations and road maps to guide and monitor program activities

- Visibility and audience appeal to ensure that all subgroups within the workforce are addressed

49.3.1 In-Place Information Security Policy.

Security objectives must be embodied in policies that clarify and document management's intentions and concerns. Policies are an organization's laws. They set expectations for employee performance and guide behaviors. An effective information security policy includes statements of goals and responsibilities and delineates what activities are allowed, what activities are not allowed, and what penalties may be imposed for failure to comply.

Effective information security policies show that management expects a focus on security. Well-defined security policies make it easier to take disciplinary action against those who compromise security. Established policies are also useful in dealing with personality types who will not do something until management tells them to.

A cohesive information security awareness policy, tailored to the organizational culture, gives the total information security program credibility and visibility. It shows that management recognizes that security is important and that individuals will be held accountable for their actions. As Daryl White, chief information officer for the U.S. Department of the Interior, said, “You can't hold firewalls and intrusion detection systems accountable, you can only hold people accountable.”13

An awareness policy should address three basic concepts:

- Participation in the awareness program is required for everyone, including senior management, part-time and full-time staff, new hires, contractors, or other outsiders who have access to the organization's information systems. For example, new hires might be required to receive an information security awareness orientation briefing within a specific time frame (e.g., 30 days after hire) or before being allowed system access. Existing employees might be required to attend an awareness activity or take a course within one month of program initiation and periodically thereafter (e.g., semiannually or annually). Existing employees might also be required to refresh their security awareness when the organization's IT environment changes significantly.

- Everyone will be given sufficient time to participate in awareness activities. In many organizations, security policy also requires that employees sign a statement indicating that they understand the material presented and will comply with security policies.

- Responsibility for conducting awareness program activities is assigned. The program might be created and implemented by one or a combination of: the training department; the security staff; or an outside organization, consultant, or security awareness specialist.

49.3.2 Senior-Level Management Support.

Senior management must be committed to information security and must visibly demonstrate that commitment by example (e.g., signing the launch memo that introduces an awareness program or activity, participating in awareness activities, and encouraging others to do so), by providing an adequate budget, and by supporting the security staff. Organizational leaders must understand and support the program as well as provide oversight. Recent years have shown a significant shift in responsibilities from a compliance officer or committee to the highest levels of an organization.

For example, ChoicePoint Inc., a data broker, was duped by thieves (social engineers) into turning over private data on more than 160,000 people. On January 26, 2006, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) and ChoicePoint reached a $15 million settlement, which included $10 million in fines. This is the largest civil penalty imposed by the FTC to date. In addition, ChoicePoint is required to submit to independent audits of its procedures every two years for the next 20 years.14 U.S. Senator Charles E. Schumer, who introduced a data security bill in 2005, said that “the settlement was not punitive enough.”15

Poor security measures can be costly: in damage to the organization's brand or reputation, in impact on operations, and in actual and potential lawsuits. The media will not hesitate to report on any type of security threat or breach. Stories such as this one are a wake-up call. This new story highlights the need for senior executive commitment to the security function.

Senior managers should see information security as a way to protect the organization's reputation. It protects customer confidence and market valuations, and it delivers a competitive edge. Security is not just about reducing risk. In today's e-commerce environment, effective information security can increase business and profits. Top management should believe that security is not solely a risk avoidance measure (like an insurance policy). Security and awareness programs should be seen as an e-business supporter and enabler.

49.3.3 Example.

Senior management must lead by example. If senior managers do not take security seriously, the program will lack credibility. For example, if the security policy prohibits employees from bringing software from home for use on the organization's PCs and senior executives are seen using personal software on their office system to evaluate their stock portfolios, employees will perceive the policy as inconsistent, unfair, and not universally applicable.

49.3.4 Budget.

Demonstrated, documented top-management support prevents middle managers from denying requests to fund information security. Managers often do not allocate employee time for security awareness activities because they do not see a direct connection to the bottom line for which they are held accountable.

Some security analysts recommend that 40 percent of an organization's security budget be spent on awareness measures.16 The National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) offers four approaches to identifying funding requirements for awareness and training programs. These are:

- Percent of overall training budget

- Allocation per user by role

- Percent of overall IT budget

- Explicit dollar allocations by component based on overall implementation costs17

49.3.5 Security Staff Backing.

Senior managers must stand behind the organization's policies and the security staff charged with enforcing those policies. This is especially important in areas where security and convenience conflict, such as enforcing a control that removes system access for users whose records show that they have not completed a required awareness refresher activity.

49.3.6 Reward for Good Security Behaviors.

Often, management wants to treat security as a core requirement. Managers may believe that security is part of everyone's job and no special recognition or incentives should be provided. This approach does not work well because security tends to be outside the normal business process. For example, if everyone only does what they are supposed to do, then we really do not need security controls. Unfortunately, if we do not have effective controls, we find out that there is noncompliance only after something bad happens (e.g., customer data are compromised).

Managers who treat security as a core requirement and do not explicitly promote and identify good or poor compliance are generally assuming that they will be able to identify noncompliance from the information they receive from normal businesses activity. This is not a correct assumption. For example, customer data may be compromised with no impact on the business process.

For a number of years, government agencies held the same perception, that security was a core function and did not give it any special emphasis. This changed as the number of incidents and their impact grew. The increase in security losses resulted in legislation requiring that agencies maintain security awareness and training programs. This resulted in improved security environments.

One of the key issues that managers need to learn and understand is that security is a special concern that must be emphasized routinely if assets are to be adequately protected. Security should be integrated with performance appraisals. “Personnel become motivated to actively support information security and privacy initiatives when they know that their job advancement, compensation, and benefits will be impacted. If this does not exist, then an organization is destined to depend only upon technology for information security assurance.”18

49.3.7 Destination and Road Maps.

Ideally, the goals (destination) of an awareness program should be specific, realistic, and measurable. Victor Basili of the University of Maryland developed an approach for metrics where the metric is created as the final step of a process called Goal-Question-Metric.19 He recommends defining a goal, for example: “Goal—decrease inappropriate Web site visits.” Next, create a question that will indicate whether the goal is being met or not: “Are staff continuing to visit Web sites that they should not?” Then, and only then, create a metric that will support the goal. The metric would be the number of attempts to access inappropriate Web sites, such as illegal or pornographic material. This information can be extracted from Web filtering products. This offers several benefits:

- It's an automated metric.

- It's easy to collect.

- It will give an idea of what the organization's users are doing.

Reaching an identified security awareness destination is easier with a road map or plan. An anecdotal story about Abraham Lincoln tells of his statement that if he had eight hours to chop down a tree, he would spend the first six sharpening his ax. Lack of planning usually means that time is spent reacting to events rather than being proactive and prepared. It takes great effort to chop down a tree with a dull ax. Similarly it is much harder to create, manage, or measure the effect of an unplanned awareness program than a planned program with defined objectives, assigned responsibilities, and management direction.

As with Lincoln sharpening his ax, planning promotes awareness activities that are carefully designed to elicit specific, positive responses. Plans should also be flexible to address changes in organizational structure, organizational objectives, and applicable threats and vulnerabilities. This flexibility should also allow incorporation of particularly relevant current events. For example, an awareness activity might emphasize the offering of rewards by Microsoft for help in capturing virus writers as evidence that security issues are getting high-level attention.

The security awareness plan should contain these elements:

- A description of the organization and its IT culture (culture is the instinctive behavior of individuals within an organization), including assigned roles and responsibilities

- The status of the organization's current efforts (can include baseline)

- An approach to ensure senior management support

- A determination of awareness needs (topics)

- Program goals and metrics

- A description of how staff will be motivated

- A description of methods and materials to be acquired, created, and/or modified

- A schedule showing actions to be completed and who is responsible for ensuring their completion (including program evaluation and updates)

A baseline will establish where the organization stands with regard to its security awareness efforts and program. It may be that the baseline is zero and a program has not been implemented. In that case, the organization may take a survey to find out how people in the organization view security and how familiar they are with security policies. The results of the survey would become the baseline. Where a program has been implemented, the organization may choose to document the level of awareness so that over time other measurements can be taken to show changes.

A security awareness program should be an ongoing effort. Some organizations offer a security awareness orientation to new employees and regular reinforcement for all employees at various times throughout the year. Doing so provides spaced repetition of the material and reinforces learning. Some organizations address security awareness on a monthly basis with newsletters, posters, screen savers, contests, surveys, and online modules. Other organizations offer awareness courses that are updated annually and provide reinforcement at various times, such as on November 30, International Computer Security Awareness Day. NIST SP 800-5020 presents a detailed awareness approach for establishing and maintaining a security program, including an appendix with a sample awareness and training program plan template.

49.3.8 Visibility and Audience Appeal.

An effective awareness program cultivates a professional, positive, and visible image. A visible program demonstrates the value of the awareness activities, raises employee morale, and encourages the support of the general workforce. The more methods used to spread the message, the more visible the program will be. An awareness program that uses computer-based courses, posters, acknowledgment statements, newsletters, contests, and videos will reach more people than a program that consists of posting security policies to the organization's intranet and sending a memo advising staff to read the policies.

Security awareness programs that show the organization's concern for employees' IT security well-being at home (for telecommuters and others who use computers at home) and while traveling are better received than programs that ignore such issues. This is because the radio station that most people are tuned to is “WII FM,” or What's in It for Me? Whether the target audience is all end users or senior management, showing them how they will personally benefit from improved security awareness contributes to program success. Viewing security as a service with the entire organization as a customer highlights the importance of marketing security to management and staff.

Common mistakes in security awareness programs include not fitting the program to the environment, using unmodified educational materials, and having no consideration for the learner.21 Learners should be able to relate to the awareness materials and apply the materials to their jobs. Organizations should build awareness programs around their business environment instead of purchasing ready-made awareness materials or copying a program from another organization without modifying it.

Joseph A. Grau, former chief of the Information Security Division at the Department of Defense Security Institute, believed in the importance of marketing security and often pointed out that customers actually pay for security services. For example, managers pay for enforcing the requirement to lock a classified document in a safe rather than leaving it on a desk, with labor hours. Other methods of payment are in the form of energy, attention, and concern for security matters, such as taking time to identify and report a potential security incident. Even egos are part of the payment for security when “scientists, researchers, technical specialists, engineers, and management personnel must refrain from communicating their successes to friends, family, and peers to protect sensitive, company private, or classified information.”22

49.4 OBSTACLES AND OPPORTUNITIES.

Starting an awareness program is not as easy as one might expect. Although senior managers seem to recognize the benefits of an awareness program when asked, they may still be reluctant to devote financial resources and staff time to it. It is relatively easy to identify the cost of an awareness program, but it is difficult to quantify its benefits. This is a primary reason why the U.S. Government has made maintenance of a computer security awareness program mandatory.23

The basic challenges faced when starting and maintaining an effective awareness program include gaining management support, gaining union support (where applicable), overcoming audience resistance, and addressing the diffusion of responsibility.

49.4.1 Gaining Management Support.

Management provides essential ingredients to a security awareness program: credibility, supervision, resources, and advocacy. Credibility comes when management complies with the security rules. If managers do not comply, then there is no reason to expect anyone else to comply. Employees will generally follow the lead of their managers, who must be role models for good security. When managers are seen to ignore policies, their subordinates quickly imitate the managers' behavior. The problem then spreads throughout the organization.

Given that most security incidents stem from errors and omissions, managers should review performance records. They should analyze each incident that causes a loss or damage to identify the cause. Certain employees may be associated with unusually high or low rates of specific problems. Analysis can reveal learning opportunities that can benefit the entire group. Managers should let workers know that they are being monitored.

Management allocates resources for the awareness program, visibly demonstrating that their support for the program is genuine. Managers must use rewards and penalties to reinforce or change behavior. They should emphasize and reward job performance that supports the positive objectives of security, profitability (for companies), productivity, and growth of the organization. Managers must also support the program by supporting the security staff and showing that computer security is good business. If management does not show that awareness has a positive return, it will be difficult to justify consistent funding. To assist management in these tasks, it is important to keep management informed, speak their language, and provide proof of impact.

49.4.2 Keep Management Informed.

Managers need enough information to allow them to understand security concerns, make informed comments, and respond knowledgeably to questions. To get this information to management, identify management reporting and communication mechanisms, such as progress reports, management briefings, and program reviews, and contribute information on security awareness program activities. Include updates with metrics that show performance measured against program goals.24

Timing can also be important as support for security is strongest after a breach when the costs of poor security become apparent. Such costs can be summed in a dollar loss, which includes the cost to notify those affected, customer dissatisfaction and defection, investigations, lawsuits, and other losses incurred by the breach. In many cases, the cost of a breach quickly exceeds security program costs. It is important for management to be careful not to react in such a way that gives the impression that incident clean-up is recognized, but ongoing compliance is not.

49.4.3 Speak Their Language.

To communicate with management, the IT staff concerned with awareness should consider these issues:

- Present realistic information rather than either overstating threats or fears. Be careful not to provide a false sense of security by overemphasizing positive aspects in an attempt to keep the program from being seen as a problem child.

- Present reasonable suggestions for solutions, along with problems and concerns.

- Prepare a written and verbal presentation so that if the allotted time is cut, you will be able to condense the verbal presentation and leave the written one, thereby delivering the complete message.

- Remember the budget—include costs involved and where possible reflect the anticipated benefits (e.g., fewer violations, increased compliance, better audit findings, reduction in misuse of IT assets or personnel time).

- Remember the ecology—ecology is the study of the relationship between organisms (users, systems, etc.) and their environment (hardware, physical access control, etc.). “The ecological aspects of security assert that you cannot afford to focus on one portion of the system without keeping track of the impact of each decision on the health of the ecosystem.”25 Be aware of the impact of the program on the entire organization and its mission. Management concerns include the amount of time that staff spend away from their jobs to satisfy administrative requirements.

- Management resistance is often based on expending funds on something perceived as a low priority or on concerns about balancing security with operational needs. Although the time and effort to build a strong security program are not trivial, it is far less by comparison with the time and effort required to deal with just one serious incident. For example, in 2007, the FTC “received over 800,000 consumer fraud and identity theft complaints. Consumers reported losses from fraud of more than $1.2 billion.”26 Using effective security awareness to avoid being targeted by class-action lawsuits for loss of control over personally identifiable information is a rational strategy.

- Some security professionals recommend pointing out that insurance policies require continuous funding but are not often used; however, few organizations choose to forgo those costs.27 Another incentive for organizations is that many contracts require information security programs—especially when the contract is with the federal government or if it deals with intellectual property belonging to customers (e.g., contracts for hardware or software design services).

49.4.4 Gaining Union Support.

John Ippolito, CISSP and coauthor of NIST SP 500-16, says in correspondence with this author: “Mention unions when developing an awareness program and the response ranges from a quizzical look to a sneer. People with a quizzical look have generally never worked with a union and fail to see their role in an awareness program. Those who sneer at the mention of union participation have typically had past efforts blocked by union action.”

Unions can be a partner or an impediment to an awareness program or anything in between. Often their role depends on how they are approached. Unions look after the best interests of their membership. An awareness program is trying to communicate computer security roles and responsibilities to that membership. Thus, union and program objectives, although different, are not in conflict. To gain union support, sell (present) your program as being in the best interests of union membership. Tips to accomplish this objective include:

- Bring in the union representatives early in the program development phase. Union representatives do not like to be ignored, especially when their membership is involved. If union representatives are presented with a fully developed program, their first response may be to think that it is detrimental to the membership; otherwise you would have given them more of an opportunity to contribute to its development. This thinking may then result in a micro-review, in which union representatives look for anything, no matter how small, that might be interpreted as contrary to the interests of union members.

- Be sure that the representatives understand that the objective of the computer security awareness program is to create within the workforce an understanding that there is a problem (i.e., the potential for a security incident) that can adversely affect the ability of their membership to get their job done. Thus, program participation is beneficial to their members, and it will help them reduce operating costs without staff reductions.

- Make it clear that the awareness program creates no new responsibilities. The awareness program is intended to help the workforce members recognize potential problems and follow existing security procedures. Ask the union representatives for examples of work situations that might be appropriate to highlight potential security issues.

- Be careful when suggesting any employee testing. Unions often interpret testing, especially when results are recorded, as a management mechanism used to limit the ability of their members to advance. Even a simple pass/fail test can create a union issue as the union will seek clarification about what happens if a person does not pass the test. At the awareness level, recording test or quiz results can be counterproductive and can create anxiety. The best approach is often to ask challenging questions and allow for safe failure, in which students can learn from their mistakes without penalties. Often a goal of an awareness program is to take away some of the fear and ignorance that have traditionally surrounded IT security by allowing people to learn in a nonthreatening environment.

49.4.5 Overcoming Audience Resistance.

Another common obstacle is audience resistance. A story about a millionaire who threw a large pool party at his mansion illustrates this issue. The pool contained four alligators, and the millionaire announced that he would give $100,000 or a new Ferrari to anyone who would swim the length of the pool. A large splash immediately followed his announcement. The crowd watched a man frantically swimming to the other end. “Well done!” said the millionaire. “Which will you have, the money or the car?” The wet and angry man answered, “I don't care about your prize; I just want to know who pushed me.” This is how some end users feel about mandatory awareness courses and activities. It does not matter how good the activity or reward; they just do not want to be told that they have to do it.

In many organizations, a positive approach is more effective than a negative one. Programs that rely on FUD (motivation by fear, uncertainty, and doubt) or use negative phrases such as “failure to attend” may not be as effective, because such statements are viewed by some employees as challenges, whereas others see them as empty threats. In addition, such statements can be offensive to those employees who are always cooperative. It is often better “to encourage participation, expect compliance, and deal with the no-shows later.”28

An awareness program must address the total organization. This includes the naive user, the new user, the power user, and even those who think that computer security is worthless and does not apply to them. Given this audience diversity, the content must be structured so that the same level of awareness can be communicated using a variety of techniques. For example, password protection might be best communicated to the naive user through a computer-based war story, whereas the same concepts might be best communicated to the power user with a brief statement of the organizational requirements on a poster or reminder memo.

Although the basic technology components may be similar from one organization to the next, the manner in which they are configured is often different, as is the terminology used to refer to them. For example, some organizations use the term “desktop” and others the term “workstation” to refer to the computer installed at an end user's location. These seemingly trivial differences can make a one-size-fits-all awareness approach fail.

49.4.6 Addressing the Diffusion of Responsibility.

One result of addressing the entire organization with a single message is a diffusion of responsibility. When people are in a group, responsibility for acting is diffused. The security awareness program must convey that each individual is responsible for taking action to prevent or report breaches, regardless of how many others may have noticed the same symptoms or other factors.

To illustrate the diffusion of responsibility, researchers conducted an experiment where a student alone in a room staged an epileptic fit. When there was just one person listening next door, that person rushed to the student's aid 85 percent of the time. However, when subjects thought there were four others also overhearing the seizure, they came to the student's aid only 31 percent of the time. In another experiment, people who saw smoke seeping out from under a doorway reported it 75 percent of the time when they were on their own but only 38 percent of the time when they were in a group.29 Providing individual reinforcement in addition to group activities may mitigate this diffusion of responsibility.

49.5 APPROACH.

Raising awareness is similar to social marketing, which uses advertising techniques to inform the public of societal concerns, such as the campaigns to reduce smoking or decrease the use of alcohol on college campuses.

49.5.1 Awareness as Social Marketing.

The marketing concepts of message, product, and market apply in a security awareness campaign. The message is the need for security, the product is the practice of security, and the market is all employees. Communication is the essential tool, and the information disseminated becomes the foundation on which behavioral change is built.

Research and planning are essential and should result in a clear strategy that:

- Defines program objectives.

- Identifies primary and secondary audiences.

- Defines information to be communicated.

- Describes approaches that fit the organizational culture and structure.

- Describes benefits that accrue to the audience.

Research may be conducted by observation, surveys, tests, and interviews. Review help-desk statistics and trends for indications of actual and potential security incidents and evidence of training needs. For example, a large number of password resets might indicate that password procedures need to be reviewed or that users need additional training. Ask the staff how they would break into the system—the people closest to the system ought to know its vulnerabilities and should be thinking about how to fix them. Ask them to consider such questions as “Are security breaches predictable?”

Pretest materials before distributing them. Pretesting provides evidence that materials are reaching your target audience with the intended message. It can also avoid embarrassing situations, such as occur after distributing a poster on which punctuation or the lack of punctuation changes the message (e.g., “Slow Work Zone” instead of “Slow, Work Zone”). Pretesting may be accomplished using focus groups, providing materials to a single unit within the organization or through group or individual interviews. In all cases, the evaluation should include a set of multiple choice or ranking questions with one or two open-ended questions. This analysis approach facilitates data comparison and aggregation. The question set should be structured to determine the message received and the level of experience (novice, beginner, user, power user) required to understand the material and receive the intended message. The questions should also be structured to avoid leading the respondent.

49.5.2 Motivation.

An organization truly dedicated to security will develop an effective security motivation program along with or as a part of a continuing awareness effort. It should use the following motivators:

- Anticipation and receipt of rewards

- Fear and experience of penalties

Other (less controllable) motivators include: character, loss experience (self and others), professional and company loyalty, self-interest (protection of personal investment and reputation), desire to excel beyond peers, and convenience.

M. E. Kabay writes of a security officer who experimented with reward and punishment in implementing security policies. Workers were supposed to log off their terminals when leaving the office, but compliance rates were only 40 percent. In one area, the security officer put nasty notes on terminals that were not logged off and reported offenders to their bosses. In another area, the security officer identified those users who had logged off and left a chocolate candy on there keyboards. After one month, compliance in the punished area had risen to 60 percent. Compliance in the area that received the candy had reached 80 percent. (For fuller discussion, see Chapter 50 in this Handbook.)

An awareness program seeks to change attitudes and behaviors that may have been practiced for a long time in company procedures or become habits that are now part of the organizational culture. Change (positive or negative) is often met with resistance simply because people do not like change. An awareness program must consider this natural workforce resistance to change by appealing to complementary attitudes or preferences. For example, the practice of password sharing with new employees to “get them on the system sooner” may be widespread. By showing that people are respected and recognized in the organization for protecting system access, rather than placing system assets at risk, the awareness campaign may change this behavior.

Security consultant Parker said:

I see poor security in every organization no matter how good the information security staff, awareness program, and technical controls may be, because of the lackadaisical, unsustainable performance of the organization's staff and managers to make the bothersome safeguards and security practices effective. They give lip service to security; they have bursts of security efforts when they are being watched or have suffered a loss, but support ultimately deteriorates for lack of a natural, ongoing motivation in the face of the overpowering pressure of job performance and finding the convenient way to do things. In contrast, computers maintain security, because security is built into their performance (if users and administrators do not tamper with it).

His conclusion was that security should be built into the performance of people as well as into the performance of our computer systems.30

Rewards and penalties are the traditional job performance motivators in any employee/employer or contractual relationship. They are useful for motivating security as well. Rewards usually involve praise and recognition, job advancement, and financial benefits (often in the form of specific bonuses for exemplary behavior). Rewards could also be prizes for exemplary security performance (e.g., winning a competition among groups for the fewest guard-reported or auditor-reported security lapses). Rewards could include recognition letters, pins, plaques, additional leave, or car parking privileges.

Penalties often involve the loss of perks, position, or remuneration; leave without pay; being fired; or legal action. A security consultant tells of a manager who publicly posted the name of anyone who revealed a password, and required everyone in the group to immediately change their passwords. This produced peer pressure to keep passwords secret because no one liked having to learn a new one.

Studies of what workers want from their jobs were conducted in the 1940s and repeated in the 1980s and 1990s. Managers identified good wages, job security, and promotion/growth opportunity as the primary reasons that their employees worked. When workers and supervisors were asked to rank a list of motivators from 1 to 10 in order of importance to workers, workers rated “appreciation for a job well done” as their top motivator; supervisors ranked it eighth. Employees ranked “feeling in on things” as being second in importance; their managers ranked it last at number 10.31

Security controls are generally viewed as an impediment to getting work done. The workforce needs to be motivated to comply through an awareness message that makes it clear that the need for security has been balanced against its impact on business processes. This message must be carried forward to system designers so that they also understand that cumbersome controls that are too disruptive to business processes will create an environment hostile toward security and are an incentive to bypass controls to meet schedules and production objectives.

Making security a part of employees' job performance will remove the conflict between job performance and security constraints. If we do not add security of information to the motivators of job advancement and financial compensation, there will be conflict, and we will continue to have superficial security.

Human resources (HR) departments often strive to keep the appraisal process from being diluted with too many evaluation subjects, and especially those that have less tangible means of performance measurement, such as security. Security consultant Parker tells of an HR manager who believed that security should be treated the same as nonsmoking, using the Internet and telephones for personal purposes, and parking regulations. The rules are posted, and if you do not follow them, you suffer penalties up to the severest one of losing your job. The reward for obeying the rules is that you get to keep your job.

The HR manager

failed to see the significance of information security for the organization, its strategic value, and possible conflict with other job performance. We need top management support to convince HR and line managers to incorporate security providing both rewards and penalties. These motivational efforts should be the objectives of security plans presented to top management until they are achieved.32

Audience perceptions and cultural characteristics are factors that may be used in structuring motivational materials. Some of these factors are shown next.

- People want to conform to the organizational performance norm (i.e., they generally do not want to stand out in a crowd). Thus, show that security compliance results in positive feedback, whereas prosecution of violators is noisy and intended to cause embarrassment.

- People are superstitious. That is one reason they pass on chain letters and often open or read e-mails with a subject line that indicates bad luck will follow if they do not continue the chain. Motivate your audience to change their perception of the superstition and alert them to its use as a tactic of criminals.

- People are curious. That is the primary reason why so many virus attacks are successful. People open an e-mail because the subject line makes them curious about the message contents. For example, the message “Your Account is Overdrawn,” will make many people open a message to see what account or how much over. Awareness techniques can take advantage of people's curiosity by creating multilevel messages, such as this one patterned on the Burma Shave model of stretching a message over a series of signs:

Hackers send e-mail

With subjects enticing

To open the message

And the virus it's hiding

Fear is often used as a motivator; however, the primary value of scare tactics is to attract audience attention. Learning communicated through fear is generally retained only in the short term. People follow messages communicated through fear, but their compliance quickly falls off when nothing bad happens. For example, if the message is “Open an e-mail attachment and you may get a virus that destroys your hard disk,” every time an e-mail attachment is opened and nothing happens, the fear associated with this message is reduced. Eventually, opening an e-mail attachment will be performed without concern—until a virus actually does strike.

Therefore, fear should not be used as a primary motivator. However, if you do decide to use fear as a motivator, be prepared to back it up with consequences and publicity regarding every security incident. Although you may use fear to attract attention, a more effective delivery approach will have a positive spin. There should be more emphasis on how security measures can help your audience get the job done than on how many days they will be suspended if they fail to comply. Demonstrate that the courage and independence it takes to resist appeals from friends and coworkers to share copyrighted materials illegally are rewarded (i.e., those who follow the rules are seen as praiseworthy and not as weaklings).

Employees rarely see that their changed security practices result in any change in risks. Risk reduction efforts will be eroded if workers see that the security they support has little bearing on the kinds of losses that occur. If employees see inconsistencies of intense security at some times and little or no security at others, this will also detract from risk reduction efforts. Workers who ask, “Why are we locking the doors but leaving the windows open?” will not be motivated to increase security.

It is better to motivate staff with rewards for the positive and measurable objective of due diligence than with the negative approach of risk reduction.

Due diligence involves using generally accepted good practices, meeting the requirements of laws and regulations, achieving security effectiveness relative to others' efforts (including competitors), and satisfying the demands of customers and shareholders. It is achieved by benchmarking, using security products and services, and using the current common body of safeguard knowledge. Due diligence is a more tangible objective than risk reduction.

Failure to properly tailor motivating techniques to your audience often results in these problems:

- Loss of the audience's attention. The awareness message is never communicated; thus, workforce behavior remains unchanged.

- Alienation of the audience. The awareness message is communicated, but the workforce perceives the message as an incentive to work against security objectives.

- Trying to do too much. Awareness is not training or educating. If the awareness audience is bombarded with everything that a security officer or system administrator should know about security, the awareness message will be lost and the audience turned off. Like an exercise program, awareness material is best when delivered in small increments, over an extended time frame, and is targeted to establishing the basic understanding that there is a security problem.

49.6 CONTENT.

Awareness is intended to change individuals' behaviors so that they recognize potential security incidents and react appropriately. Awareness materials are generally broad in coverage but limited in depth (i.e., awareness covers a lot of ground but does not dig very deep holes). Using such materials avoids encroaching on training, which is in-depth but is also role based (i.e., provides the security training specific to an individual's organizational responsibilities).

The NIST recommends these 27 topics for security awareness programs:

- password use and management,

- protection from malicious code,

- policy (implications of noncompliance),

- unknown e-mail attachments,

- Web use,

- spam,

- data backup and storage,

- social engineering,

- incident response,

- shoulder surfing (watching over someone's shoulder as he or she types),

- changes in system environment,

- inventory and property transfer,

- personal use and gain issues,

- hand-held device security issues,

- encryption and transmission of sensitive data,

- laptop security while on travel,

- personally owned systems and software at work,

- timely application of system patches,

- software license restriction,

- supported or allowed software on organization systems,

- access control, individual accountability,

- user acknowledgment statements,

- visitor control and physical access to spaces,

- desktop security,

- protection of information throughout the life cycle,

- and e-mail list etiquette.33

To avoid overwhelming the audience, NIST also recommends that these topics be explained one or a few at a time: “Brief mention of requirements (policies), the problems that the requirements were designed to remedy, and actions to take are the major topics to be covered in a typical awareness presentation.”34

Rebecca Herold lists 59 topics for security awareness and training and 20 target audiences, including customer privacy advocates, executive management, mid-level managers, IT personnel, all personnel, new personnel, customer service and call centers, and trainers. Topics to be addressed include security of third-party access, security in job definitions and performance appraisals, business continuity planning, backups and logging, personal information privacy, electronic commerce, and mobile and remote computing.35

At the most basic level, an awareness program should address two questions appropriate to every audience:

- What does a security incident look like?

- What do I do about it (security)?

“All individuals in the workforce are important to fulfilling organizational goals” is a message that needs to be communicated through an awareness program. People need to be reminded of the value of their work because they often do not understand how their work contributes to the business process. In addition, organizations provide their workforce with significant assets in the form of equipment, software, and data. Compromise or loss of these assets could cause significant harm to the organization's solvency and make it subject to legal liability due to data compromise.

Individuals often are the first to detect security incidents. The actions they take or fail to take subsequently determine the level of damage. Further, individual compliance with established security policies and procedures can make or break a security environment. For example, an individual leaving an unattended desktop connected to the corporate network places all the interconnected assets at risk.

49.6.1 What Do Security Incidents Look Like?

What do security incidents look like? What does a criminal look like? Both questions have no single answer. There is no single criminal profile, and there is no single set of characteristics that fits a security incident.

An awareness program needs to communicate that individuals are not expected to report only verified security incidents. The determination as to whether a particular event is or is not a security incident is an after-the-fact decision made by the technical staff after evaluating the event, its cause, and impact. Individuals are expected to report anything that “might be” a security incident. Thus, the awareness materials should explain that individuals should report erratic or abnormal system behavior or such occurrences as phone calls from “equipment vendors” asking for user passwords, unusual processing slowdowns, dial-in circuits that are always busy, or anything else that appears strange or differs from the normal processing environment.

49.6.2 What Do I Do about Security?

Individuals should be made aware of how to react to incidents (e.g., a call that the individual suspects is from a social engineer, an unknown visitor in the work area, a suspected viruses, or a bomb threat). Tip sheets with “Recognize—React” information or bulleted lists explaining “What You Can Do” for various security topics is useful. Explaining the role of the entire workforce (i.e., it is everybody's responsibility) in security comprises the bulk of the awareness program. The material communicated must be coordinated with organizational policies, and it must be limited in depth—do not cross over into training, or you will lose your audience. The material should also be tailored to the organization's technical architecture and configuration (e.g., do not explain the threats to wireless communications if wireless is not present; do not talk about mainframe security when there is no mainframe).

49.6.3 Basic Security Concepts.

Risks, threats, and vulnerabilities are basic concepts of security that must be generally understood so that security and the individual's relation to security can be placed in its proper perspective.

- Risk. The entire workforce should generally understand the concept of risk. The basic understanding that should be communicated is that no useful system is without risk and that security controls provide reasonable levels of protection, not absolute protection. Thus, it is critical that individuals report anomalies that may indicate an attack or security incident.

- Threat. A threat is always present, and neither the individual nor the organization can affect when or if a threat will affect or attack the organization (i.e., threats are always there, and you cannot change that). This is a simple but often misunderstood concept. Awareness programs need to address threats so that the workforce will understand that systems operate in an unfriendly environment and that is why it is so important for everyone to help maintain and strengthen the security environment.

- Vulnerabilities. Threats cannot have an impact on a system unless there is vulnerability. Vulnerabilities include failure to change passwords, update or patch operating systems, or report potential incidents; lack of a surge suppressor; verbose information broadcasts on networked servers; and many others. Individuals can identify vulnerabilities (e.g., a desktop without a surge suppressor). Awareness material should provide examples of how to identify vulnerability and the reporting process to ensure that the vulnerability is addressed.

49.6.4 Technical Issues.

Technical issues are the specific threats, system components, controls, or control techniques that should be considered for inclusion in an awareness program. The following are examples:

- Access control and passwords: password creation, change, resets, deletion.

- Social engineering: include specific examples of scripts that might be used.

- Malware: how it can damage an information system, and how the organization handles viruses, hoaxes, and spam.

- Data sensitivity, including privacy issues: vulnerability of payroll, medical, and personnel records.

- Data handling: including transmission (wireless or hard-wired), storage, and backups.

- Appropriate use of the Internet: including the World Wide Web, peer-to-peer file sharing, and e-mail.

- Mobile computing: for those who work from home or on travel.

- Home PCs: how security is important at home as well.

- Laptops, PDAs, handheld devices, and mobile phones

Each item included should be tailored to the specific user environment and organizational policy.

49.6.5 Reporting.

The primary responsibility of all individuals within the workforce is to comply with security policies and procedures and report potential vulnerabilities and potential security incidents. This section presents the topics that should be addressed regarding reporting in an awareness program.

- Who. Individuals within the workforce should be given the contact information, such as telephone and pager numbers, e-mail, and Web site URLs (addresses) of the security staff, the incident response team, and help desk personnel.

- What. The most critical information is who is reporting the incident; its symptoms, date, and time; and actions taken. Other types of information that are helpful when reporting a suspected problem include the affected system(s) or site(s), hardware and operating system, duration of incident, connections with other systems that were active, damage, and assistance needed.

- When. Users need to know that, with security events, time is of the essence. Reporting the problem immediately can often prevent or limit the scope and severity of the damage. Users should know not to delay reporting.

- How. Workers should be given instructions for reporting suspected problems by telephone or by e-mail using a system that is not suspected of being under attack.

49.7 TECHNIQUES AND PRINCIPLES.

Presentation of awareness materials is crucial. If the employee's reaction is “I knew that” or “so what?” the program is not effective. Desired responses include:

- “I never thought of it that way.”

- “That surprises me!”

- “That's a great idea!”

- “I'd almost forgotten about that….”

- “I can use this.”

49.7.1 Start with a Bang: Make It Attention Getting and Memorable.

Experienced, in-demand speakers do not start a presentation with a long, dry, boring introduction that lists every law, regulation, policy, standard, guideline, or other requirement that relates to information security. If there were such a thing as a deadly sin in an awareness program, it would be to bore the audience. For an awareness message to be effective, the audience must identify with the idea, concept, or vision.

49.7.2 Appeal to the Target Audience.

A U.S. Critical Infrastructure Assurance Office publication states: “The level of security awareness required of a summer intern program assistant is the same as that needed by the Director, Chief, or Administrator of the agency,”36 and U.S. federal employees must attain this security awareness within 60 days of starting work. Although workers at all levels need to have security awareness, the methods for effectively reaching different employees with the awareness message may need to be different. It is easier to hit the bull's-eye when one can focus on a specific target.

There are different audiences within all organizations, with different characteristics based on their needs, roles, and interests:

- Needs. Audiences with similar needs will have similar levels of computer knowledge and experience. End users with minimal computer experience may be intimidated by and not respond well to technical jargon. Analogies and examples are more appropriate for audiences with little in-depth computer expertise.

- Roles and interests. Awareness programs that appeal to the existing values and motivations of the target audience will be more successful than ones that try to change them. End users are usually interested in getting their job done with as little obstruction as possible. They are usually interested in knowing about the effect of security on their workload, delays, and job performance evaluations. Managers are usually interested in the bottom line and measurable results. They want to know “How much will this security control cost?” and “What kind of benefits will it bring?” Technical staff should receive materials with correct technical term usage. Otherwise, they may conclude that the information is beneath them or that it has been prepared by persons who lack technical knowledge.

To create an awareness program, first identify the audiences and conduct research to find out what they know and what questions about security they ask most often. Surveys and questionnaires can be used to reveal the starting level of awareness of security issues. They will also be useful for measuring progress after the awareness program is implemented.

Historical information can provide clues about what the audience knows and does not know. Asking the question “What security-related problems have the organization experienced?” may reveal information that can be used to tailor the awareness program.

49.7.3 Address Personality and Learning Styles.

Trainers often describe three primary learning styles: auditory, visual, and kinesthetic. An auditory learner picks up information from hearing or reading it and is effectively reached by lectures and written material. A visual learner wants to see what is being taught and prefers diagrams, charts, and pictures. A kinesthetic learner responds well to tactile input and wants to walk through the steps or learn by physically doing the task.

Yet personality styles are arguably more important than learning styles. Some people will not follow a procedure until they understand the reason for it. To reach these people, present the “whys.” If an exercise is included as part of an awareness course, once a question is answered, give learners the choice of trying again or receiving the answer. Some people learn best and have better retention when they figure out something for themselves. Others just want to see the result and move on to the next topic or exercise.

49.7.4 Keep It Simple: Awareness Is Not Training.

Awareness efforts should be simple. An objective of an awareness program is to take away the fear and ignorance that have traditionally surrounded information security. Effective awareness activities make people recognize that there is a problem and that they are part of the solution.

49.7.5 Use Logos, Themes, and Images.

Attention is a prerequisite to learning. This was recognized at least 80 years ago: “The person who can capture and hold attention is the person who can effectively influence human behavior.”37 Awareness activities and materials should be designed to attract attention in a positive way. Clever slogans and eye-catching images contribute to the program's success.

Well-designed security logos and mascots can be a source of pride and a showpiece for the organization. Images have greater impact than words. Color and design, as well as the uniqueness of the image, add to its effectiveness. The careful use of animated images in presentations, computer- and Web-based courses, and screen savers can enhance the message. A Web-based course used by many U.S. Government organizations opens with the words “What would happen if someone changed your data?” The words are an animated image that changes a few characters at a time until the message becomes completely unreadable: “Wyad ciunx safper ef stmxune khopgel joor deko?” This image makes a dramatic point about data integrity and availability.

Themes can be used to unite several concepts into a related message. The theme of “Prevention Is Better than Cure” would be appropriate for organizations that process medical data. Give-away items, such as first-aid kits with security slogans and contact information imprinted on them, could tie in to a medical theme, as could the concepts of virus checking software and backups being similar to health insurance cards in that they must be current to be of value.

The U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) celebrates International Computer Security Day each year with a different theme. The theme of a recent celebration was “Keep It Clean”; an NRC computer security officer (CSO) dressed as Mr. Clean (complete with a bald head and gold hoop earring) passed out antivirus software to employees who attended the event. A large, signed color photograph of the official Mr. Clean was on display. Another year, the celebration introduced the agency's new security mascot, Cyber Tyger. Cyber Tyger was featured on posters, on the cover of the antivirus software CD, and on buttons. Again, one of NRC's CSOs arrived in costume and delighted the visitors. In other years the themes have been “It's a Bug's Life” and “PC Doctor,” in which a “sick” PC was wheeled into the lobby on a gurney while the CSO, dressed in surgical scrubs and mask, explained the symptoms of a virus infection to visitors.

Awareness posters can be developed around a common theme, with common design elements, or a phrase or logo. A staged campaign of posters might include a series with numbers on them; for example, “85” on one and “3 million” on another. No explanation of the numbers would be given, and a mystery would develop. Later, new posters could explain that 85 is the number of reported incidents at the organization in the past year and that 3 million is the number of dollars of lost business from a distributed denial of service attack.

49.7.6 Use Stories and Examples: Current and Credible.

Stories about real people and real consequences (people being praised, disciplined, or fired) are useful in presentations and courses. Sources of stories include individuals who have been with the organization for a long time and have a “corporate memory,” news events, Internet special-interest bulletin boards, and security personnel who attend special interest group meetings and conferences.

The stories should relate to situations and decisions the audience may face. Stories about hackers accessing medical records would be useful to organizations that process medical data, whereas stories about fraud or identity theft would be of interest to personnel involved in the financial industry or the accounting function of an organization.

Awareness material must be fresh and not stale. Chef Oscar Gizelt of Delmonico's Restaurant in New York said, “Fish should smell like the tide. Once they smell like fish, it's too late.” If awareness material is not changed frequently, it too begins to smell old and becomes boring or less credible.

Credibility is crucial for an awareness program to be effective. The message should be clear, relevant, and appropriate to the real world. If the audience is required to use 15 different passwords as a part of day-to-day functions, prohibiting them from writing their passwords may not be as realistic as providing strategies for protecting the written list.

49.7.7 Use Failure.

“Expectation failure” is an important learning accelerator.38 People often do not pay attention to information they are expecting to hear or see. When an employee takes a computer-based awareness quiz and gets an answer wrong, he or she pays more attention. Yet failure should be safe and private. For this reason, computer-based awareness questions and quizzes should provide immediate feedback but should not record answers. At the awareness level, it is more important to give staff members something to think about than to have them get every answer correct. To remove anxiety, inform staff members that their answers will not be recorded.

49.7.8 Involve the Audience: Buy-In Is Better than Coercion.

People who have contributed to the awareness program with suggestions, contest entries, or focus group testing are more likely to accept and follow security controls. This assumes that feedback is given for every suggestion submitted. No feedback implies no management interest.

Awareness activities that are active and involve the audience are more memorable than passive ones. Whether in person, on a poster, or through a Web-based awareness course, involving the audience with questions such as “Did you know…?.” and “What would you do if…?” is an effective awareness technique.

Trivia questions and unexpected or counterintuitive facts are good attention getters. For example, asking this question,

In the United States, which of the following activities is illegal?

- Creating a virus that spreads through e-mail

- Disrupting Internet communications

- Failing to make daily backups of data

usually results in people choosing the first answer. The question is designed to provoke thought, because creating a virus is not actually illegal. Releasing a virus is, but that is not one of the answers. The correct answer is “Disrupting Internet communications.” The question is designed to get people to think about security in new ways.

Another good awareness technique is to use unusual or psychologically compelling questions designed to engender thought. Such questions can be given during live presentations or over the Web. For example, logic professor Rick Garlikov suggested the following sequence of questions to help end users realize that it is not only the probability of a bad thing happening but also the damage that could occur that determines how much precaution is needed.

Start out asking the audience, “How many of you see security as just being a nuisance to your doing your real work?” If people raise their hands, call on them and ask “How so?” or “In what way?” or “Why is that?” Then see what they say, and go from there with “What if…?” types of questions.

Ask how many believe that “an ounce of prevention is a pain in the neck” or “an ounce of prevention is a lot of trouble.”

Agree that we all hate to take precautions when risk does not seem likely. However, there are two factors in determining the potential damage caused by any risk situation: probability and impact. Most people only take probability into account. Offer to try a Socratic demonstration to show that probability is not the only factor to take into account:

Ask, “How many of you would play Russian roulette?”

We assume most/all will not. If someone does say he would play, ask why. See whether his reason makes any sense. If not, just laugh and go on.

Ask those who won't play, “Why not?”

Presumably someone will say something like “You can get killed,” or “It's not good odds.”

Then say, “Yes, and the odds are one in six, which are not good odds. But, I'll tell you what, let's make the odds a lot better. We'll just put one bullet in one chamber of one of 100 revolvers, so that your odds will only be 1 in 600. And we will sweeten the pot by letting you win $10 if the gun does not go off when you shoot it at your head? Now how many will play?”

If some would play under those conditions, ask them why, and let others agree or disagree.

The point is that, no matter how much you increase the odds, the risk is not worth the game because you have too much to lose and not nearly enough to gain.