27. Installing and Replacing Hardware

Upgrading Your Hardware

No matter how high the performance of your computer, sooner or later it will start to slow down as newer programs demanding faster hardware show up on your desktop. Chances are performance demands will exceed your computer’s capabilities before you or your company is ready to pop for a replacement computer. This chapter will help you make the hardware changes—large or small—you need to get the most work and useful life out of your computer. We’ll discuss how to upgrade and install hardware, add a second monitor, connect new and old hard drives, and add memory.

The single most helpful thing you can do to make your Windows 7 computer run at peak speed is to give it enough system memory (or RAM, short for random access memory). Just as a reminder, your computer uses two types of memory: hard disk space and RAM. RAM holds Windows and the programs you’re actually using, and Windows 7 wants more RAM than Windows XP, but is happy with what works for Vista (if not even slightly less). As discussed in the early chapters of this book, Windows 7 can run with as little as 512MB of RAM and an 800MHz CPU, but it will run a bit slowly, and you’ll find the experience somewhat unpleasant. Memory is inexpensive these days, and boosting your RAM to at least 1GB will make a huge difference. I discuss adding RAM and upgrading CPUs later in this chapter.

Now, if you’re already running Windows 7 on a full-bore, state-of-the-art system, and your computer has a fast video accelerator, a couple of gigs of fast memory, and fast SATA disks, there isn’t much more you can do to optimize its hardware. You might just adjust the page file sizes and certainly convert all your partitions to NTFS (which is a requirement for Windows 7), or you might add a ReadyBoost device (more on this later in this chapter). Some of the settings you can make are discussed in Chapter 22, “Windows Management and Maintenance;” Chapter 23, “Tweaking and Customizing Windows;” and Chapter 24, “Managing Hard Disks.”

Tip

![]()

This chapter just scratches the surface of the ins and outs of hardware installation and updates. If you want all the details, and I mean all the details, get a copy of the best-selling book Upgrading and Repairing PCs, by Scott Mueller, published by Que.

By the same token, if you’re doing common, everyday tasks such as word processing, and you’re already satisfied with the performance of your computer as a whole, you probably don’t need to worry about performance boosters. Your system is probably running just fine, and the time you’d spend trying to fine-tune it might be better spent doing whatever it is you use your computer for (like earning a living).

If you’re anywhere between these two extremes, however, you may want to look at the tune-ups and hardware upgrades we’ll discuss in this chapter.

ReadyBoost

Microsoft introduced ReadyBoost as part of Windows Vista. Essentially, it allowed users to allocate all or part of any single USB flash drive (which Microsoft abbreviates as UFD) or a Secure Digital (SD, SDHC, or mini-SD) memory card as an extension to cache memory available in system RAM. In Windows 7 several notable changes are introduced, including

• Vista limited ReadyBoost space to a maximum of 4GB (which is all that 32-bit operating systems can handle anyway) for both 32- and 64-bit versions. In Windows 7, 64-bit versions can allocate up to 128GB for a ReadyBoost cache.

• Vista limited eligible memory devices to UFDs and SD cards; Windows 7 works with those devices plus Compact Flash (CF), all forms of MemoryStick (MS, MS Duo, MS Pro, and so on), and most other memory cards as well. As with Vista versions, devices must meet minimum speed requirements (12.8 Mbps read/write speeds) for use as ReadyBoost cache devices.

• Vista limited ReadyBoost to a single memory device; in Windows 7 you can allocate ReadyBoost cache on multiple memory devices at the same time. When spread across multiple devices performance might not be as fast as when ReadyBoost cache comes from a single device, however.

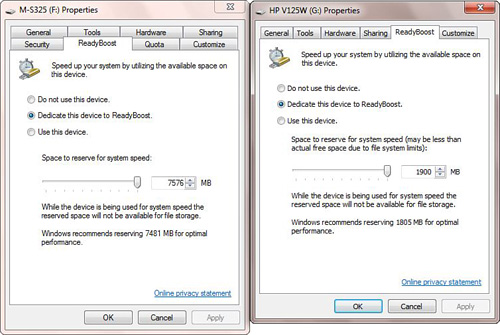

To allocate space on a memory device for ReadyBoost, right-click the drive icon in Windows Explorer, and then click the ReadyBoost tab in its Properties dialog box. Figure 27.1 shows two different UFDs in use on an x64 Windows 7 machine; the Properties dialog box on the left comes from an NTFS-formatted UFD (NTFS or exFAT are required to create a ReadyBoost cache file greater than 4GB in size), while the box on the right is from a FAT-32 formatted UFD (mixing and matching works fine).

Figure 27.1 In Windows 7, ReadyBoost cache works with multiple devices, where not all formats need be identical.

BIOS Settings

Windows 7 depends on proper BIOS settings to enable it to detect and use hardware correctly. At a minimum, your drives should be properly configured in the system BIOS, and your CPU type and speed should be properly set (either in the BIOS or on the motherboard, depending on the system). Thanks to some clever work by Microsoft’s engineers, Windows 7 boots faster than other 32-bit versions of Windows, but you can improve boot speed further with these tips:

• Set up your BIOS boot order to start with drive C: so that you can skip the floppy stepper motor test.

• Disable floppy drive seek.

• Turn off any Quick Power-On Self Tests. Some BIOSs have such an option that enables a quicker bootup by skipping some of the internal diagnostics that would usually take place on startup. It makes bootup faster but also leaves you susceptible to errors; some problems will not be detected at startup.

Upgrading Your Hard Disk

One of the most effective improvements you can make to a system is to get a faster or larger hard drive, or add another drive. SCSI hard disks used to seriously one-up IDE drives, but the new breed of Ultra DMA EIDE drives (which I call Old MacDonald Disks—EIEIO!) and Serial ATA (SATA) drives are speedy and much cheaper than SCSI. An EIDE bus supports four drives (two each on the primary and secondary channels) and is almost always built in to your motherboard. Adding an optical (usually a DVD±RW or a Blu-ray) drive claims one, leaving you with a maximum of three EIDE hard drives unless you install a separate add-on EIDE host adapter or have a motherboard with RAID support. The EIDE spec tops out at 133MBps. SATA supports one drive per channel, but the latest SATA II systems can reach top transfer speeds of 300MBps. Because optical drives also come with SATA connections these days, many new systems skip EIDE in favor of SATA.

The following are some essential considerations for upgrading your hard disk system:

• Don’t put a hard drive and an optical drive on the same channel unless you must. (Put the hard drive on the primary IDE1 channel and the optical drive on the secondary IDE2 channel.) On some computers, the IDE channel negotiates down to the slowest device on a channel, slowing down a hard disk’s effective transfer rate. Be sure that the hard drive containing Windows is designated as the Primary Master drive.

• Defragment the hard disk with the Defragmenter utility, which you can reach through Computer. Right-click the drive, select Properties, Tools tab, Defragment Now. Do this every week (or run Defrag and set up a schedule so it runs weekly), and the process will take just a few minutes. But, if you wait months before you try this the first time, be prepared to wait a long time for your system to finish. You can also purchase third-party defragmenting programs that do a more thorough job. For more about defragmenting, see Chapter 24.

• Get a faster disk drive (and possibly controller if necessary to support the drive): Upgrade from standard Parallel ATA (PATA) to SATA drives if possible. If you have slower (4,200- or 5,400RPM) drives, upgrade to quicker ones such as the increasingly popular 7,200RPM or 10,000RPM drives. The faster spin rate bumps up system performance more than you might expect. Purchase drives with as large a cache buffer as you can afford. Drive technology is quickly outdated, so do some web reading before purchase.

Tip

![]()

Many recent motherboards feature onboard IDE and even SATA RAID, which can perform either mirroring (which makes an immediate backup copy of one drive to another) or striping (which treats both drives as part of a single drive for speed). Although the RAID features on these motherboards don’t support RAID 5, the safest (and most expensive!) form of RAID, they work well and are much less expensive than any SCSI form of RAID. Just remember that mirroring gives you extra reliability at the expense of speed because everything has to be written twice, and striping with only two disks gives you extra speed at the expense of reliability—if one hard disk fails, you lose everything. You can now find external terabyte boxes with multiple drives in them that can be set up for striping or mirroring (RAID 0 or 1) at amazingly affordable prices.

Adding RAM

Perhaps the most cost-effective upgrade you can make to any Windows-based system is to add RAM. This one is a no-brainer: If your disk pauses and thrashes each time you switch between running applications or documents, you need more RAM. Although Microsoft says Windows 7 can run with as little as 512MB of RAM, we found that this results in barely acceptable behavior. At least Microsoft was realistic about it this time around. Microsoft had claimed XP could run with 64MB, but that was a stretch. Running with 64MB caused intolerably slow performance. Windows 7’s published minimum is 512MB, but if you run memory-intensive applications and want decent performance, you’ll want to up it to 1GB, if not 2.

Windows automatically recognizes newly added RAM and adapts internal settings, such as when to swap to disk, to take best advantage of any RAM you throw its way. Upgrade to at least 1GB of RAM if you can afford it, especially if your system uses the economical synchronous dynamic RAM (SDRAM) or double-data-rate (DDR) SDRAM dual in-line memory modules (DIMMs). Memory prices fluctuate constantly, but these days 2GB DIMMs sell for about $25. This is a cost-effective upgrade indeed. But be sure to get the right memory for your motherboard. A huge variety of memory technologies are out there. At the time this was written, common technologies included SDRAM, Rambus DRAM (RDRAM), DDR, DDR2, and DDR3. Memory speeds range from 100MHz (labeled PC100) to 2200MHz (labeled DDR3-2200). Also, there are error-correction code (ECC) and non-error-correcting RAM varieties (desktop and notebook PCs use non-ECC RAM).

Tip

![]()

For more about RAM developments and technology, go to http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Random_access_memory.

To find out what type of memory you need, check with your computer manufacturer or the manual that came with your computer or motherboard. Get the fastest compatible memory that your CPU can use and that your motherboard supports. You can get RAM that’s rated faster than you currently need, but you won’t gain any speed advantage—just a greater likelihood of being able to reuse the memory if you later upgrade your motherboard. Here’s a website with some good information about RAM and even possibly what kind your computer uses: www.pcbuyerbeware.co.uk/RAM.htm.

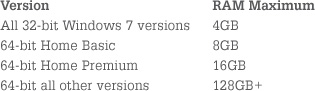

The maximum amount of RAM you can use depends on your computer’s hardware and the version of Windows 7 you are using. The following table lists the version and maximum amounts. Many last-generation computers cannot use more than 4GB of memory, and that’s all that 32-bit versions of Windows can address, even if you could plug it in without a BIOS upgrade. Check with the computer or motherboard manufacturer’s data sheets or website to figure out whether you have to flash upgrade the system board BIOS to support more than 4GB of RAM.

Adding Hardware

One of the tasks that is most common for anyone responsible for configuring and maintaining PCs is adding and removing hardware. The Control Panel contains an applet designed for that purpose, called Devices and Printers (accessible from Control Panel’s Hardware and Sound category). You can use it if the OS doesn’t automatically recognize that you swiped something or added something new, whether it’s a peripheral such as a printer or an internal device such as a DVD-ROM, additional hard disk, or whatever.

Tip

![]()

Microsoft has changed its nomenclature with Windows 7. What used to be called the Windows Compatibility List or Hardware Compatibility List (also abbreviated HCL) is now called the Windows Logo’d Products List. If you want to make life easy for yourself, before you purchase hardware for your Windows 7 system, check the lists on the Microsoft site (look for Windows 7 items at https://winqual.microsoft.com/hcl/default.aspx. Or when looking on a box in a store or online, it should have a “Certified for Windows 7” or “Windows 7” logo on it.

If you’re a hardware maven, you might visit Devices and Printers occasionally, but only if you work with non–Plug and Play (PnP) hardware. PnP hardware installation is usually effortless because Windows 7 is good at detection and should install items fairly automatically, along with any necessary device drivers that tell Windows how to access the new hardware. With non-PnP devices now nearly obsolete, you’ll only need to mess with this on rare occasions, if at all.

Note

![]()

Always check the installation instructions before you install the new hardware. In some cases, the instructions tell you to install some software before you install the new hardware. If they do, follow this advice! I have made the mistake of ignoring this and finding out that a driver has to be removed and reinstalled in the correct order to work correctly.

If you’ve purchased a board or other hardware add-in, you should first read the supplied manual for details about installation procedures. Installation tips and an install program may be supplied with the hardware. However, if no instructions are included, keep reading to find out how to physically install the hardware.

If you’re installing an internal device, you’ll have to shut down your computer before you open the case. I suggest that you also unplug it because most modern PCs actually keep part of the system powered up even when it appears to be off. Before inserting a card, you should discharge any potential electrostatic charge differential between you and the computer by touching the chassis of the computer with your hand. Using an antistatic wrist strap also is a good idea. Then insert the card, RAM, and so on.

Tip

![]()

You might be tempted to move some adapter cards plugged in to your motherboard from one slot to another, but don’t do this unless you really must. Each PCI adapter’s configuration information is tied to the slot into which it’s plugged. When you restart your computer, the PnP system will interpret the move as your having removed an existing device and installed a new one, and this can cause headaches. In some cases, you’ll even be asked to reinsert the driver disks for the device you moved, and you may have to reconfigure its software settings. (From personal experience, I can tell you that moving a modem gives Symantec PCAnywhere fits.) If you must swap slots, don’t change or mess with them all at once. Change one and reboot, and then change another. Windows 7 is better about contention and remapping resources than previous Windows versions were.

When the device is installed, power your PC back up, log on with a Computer Administrator account, and wait a minute or so. In most cases, the Add Hardware Wizard automatically detects and sets up the new device. If you must run this wizard, type hdwwiz in the Start menu search box (it’s no longer listed in Control Panel).

If you’re adding a USB or FireWire device, plugging in an Ethernet cable, or a digital camera card, you don’t need to shut down before plugging in or inserting the new device, but you should close any programs you have running, just in case the installation process hangs the computer. The computer itself (as opposed to applications) doesn’t hang often in NT-based systems such as XP, Vista, and Windows 7, so BSODs (blue screens of death) are more rare, but they can happen. Save your work and close your applications before you plug in the new device.

For non-PnP hardware, or for PnP stuff that isn’t detected or doesn’t install automatically for some reason, you can try this:

1. Type hdwwiz in the Start menu search box to launch the Add Hardware Wizard.

2. The wizard starts by advising you to use a CD if one came with your hardware. This is good advice. If you don’t have a CD, you can move ahead and use the wizard.

3. Click Next, and the wizard asks whether you want it to search for the new hardware and figure out what it is (and try to find a driver for it), or whether you want to specify it yourself. Go for the search. If you’re lucky, it will work, and you’re home free. If a new device is found that doesn’t require any user configuration, a help balloon appears onscreen near the system tray, supplying the details of what was located.

Tip

![]()

Another way to force a scan of legacy hardware is to open the Device Manager, right-click the computer name at the top of the list, and choose Add Legacy Hardware.

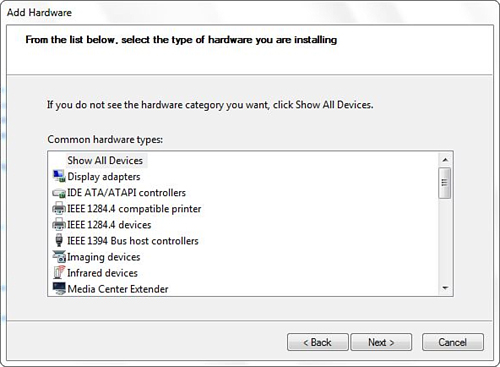

4. If nothing is found, the wizard asks you to manually select the hardware you wish to install from a list. Assuming you know what to choose, click Next. You’ll now see a list like the one in Figure 27.2.

Figure 27.2 When a new PnP device isn’t found, you see this dialog box. Choose the right category and click Next.

5. Choose the correct category and click Next. Depending on the item, you’ll next see a different dialog box. For example, for a modem, the wizard offers an option to detect and install it. For most other items, it prompts you for the make and model.

6. Choose the correct make and model. If you don’t see a category that matches your hardware, click Back and then select Show All Devices. It will take a minute for the list to be populated. The box will then show every manufacturer and the devices each manufacturer sells. With some sleuthing, you may be able to find the hardware you wish to install.

Note

![]()

Windows 7 64-bit cannot use legacy hardware as XP, Vista, and 32-bit Windows 7 can. All 64-bit drivers must be digitally signed by Microsoft, or they are not allowed to install.

Be sure you choose the exact name and model number/name for the item you’re installing. You might be prompted to insert your Windows 7 DVD so that the appropriate driver file(s) can be loaded. If your hardware came with a driver disk, use the Have Disk button to install the driver directly from the manufacturer’s driver disk or downloaded file.

Tip

![]()

In some cases, you can adjust settings after hardware is installed and possibly adjust the hardware to match. (Some legacy cards have switches or software adjustments that can be made to them to control the I/O port, DMA address, and so forth.) You might be told which settings to use to avoid conflicts with other hardware in the system.

If, for some reason, you don’t want to use the settings that the wizard suggests, you can use your own settings and configure them manually. You can do so from the Add Hardware Wizard or via the Device Manager. See Chapter 22 for details on adjusting hardware resources and dealing with resource contention. This is much less of a problem than it once was, now that virtually all modern PC hardware conforms to the Plug and Play spec.

Early in the wizard’s steps, you can specify the hardware and skip the legacy scan. This option saves time and, in some cases, is a surer path to installing new hardware. It also lets you install a device later if you want to. The wizard doesn’t bother to authenticate the existence of the hardware; it simply installs a new driver.

If a device plugs in to an external serial, parallel, or SCSI port, you might want to connect it, turn it on, and restart your system to install it. Some of these devices can’t be installed via the Add Hardware Wizard if they’re not present when the system starts up.

As mentioned previously, you can also use the Devices and Printers applet to install hardware. To add a network or wireless device of some kind, for example, click Start, Devices and Printers, and then click Add a Device. This triggers a device scan on your PC, and if Windows 7 finds something suitable, it will trigger the device installation at that point. Likewise, to add a printer you can click Add a Printer at the end of the preceding sequence. Then you will see options to add a locally or network-attached print device instead. After that, you’ll install any necessary drivers and the process will complete.

Providing Drivers for Hardware Not in the List

If the hardware you’re attempting to install isn’t on the device list, this might be because one or more of the following is true:

• The hardware is newer than Windows 7 itself.

• The hardware is old, and Microsoft did not include its driver.

• The hardware must be configured using a special setup program supplied with the device.

Tip

![]()

Use the System applet or the Computer Management Device Manager Console, not the Add Hardware Wizard, to fine-tune device settings, such as IRQ and port selections, update devices and drivers, and remove hardware. Use the Add Hardware Wizard only to add or troubleshoot hardware.

Here’s a quick way to access Device Manager: Click Start, type Device into the search box, and then select Device Manager from the results list. That’s it!

In such cases, you must obtain a driver from the manufacturer’s website (or Microsoft’s; check both) and have it at hand in some form (UFD, optical media, or on a hard drive somewhere accessible). If the manufacturer supplies a setup disk, forget my advice, and follow the manufacturer’s instructions. However, if the manufacturer supplies a driver disk and no instructions, follow these steps:

1. Run the Add Hardware Wizard and click Next.

2. Select Install the Hardware That I Manually Select from a List and click Next.

3. Select the appropriate device category and click Next.

4. Click the Have Disk button. Enter the location of the driver. (You can enter any path, such as a local directory or a network path.) Typically, you insert a UFD or optical disk. If you download the driver software from a website, save it on your hard drive. In either case, you can use the Browse button if you don’t know the exact path or drive. If you do use the Browse option, look for a directory where an INF file appears in the dialog box.

5. Assuming the wizard finds a suitable driver file, choose the desired hardware item from the ensuing dialog box and then follow the onscreen directions.

Tip

![]()

If you’re not sure which ports and interrupts are already taken, type system information in the Search box, then check Hardware Resources to identify available IRQs, DMA, and so on.

Removing Hardware

Before unplugging a USB, FireWire, or PCMCIA (PC Card) device, tell Windows 7 to stop using it. This prevents data loss caused by unplugging the device before Windows 7 has finished saving all its data. To stop these devices, click the Safely Remove Hardware icon (it’s one of the hidden icons available through the up arrow in the notification area). Unplug the device or card only after Windows informs you it is safe to do so.

For the most part, you can remove other hardware simply by shutting your computer off, unplugging it, and removing the unwanted devices. When Windows restarts, it recognizes that the device is missing and can carry on without problems. As a shortcut when you don’t want to power down completely, you can hibernate the computer and remove the item. Sometimes, this can prevent a computer from resuming properly though, so be cautious and save your work before you try this method. Test it, and if it works, you can disconnect this item during hibernation in the future, knowing that Windows 7 detects the change upon resuming.

If you want to completely delete a driver for an unneeded device, use the Device Manager. Double-click the device whose driver you wish to remove. This opens its properties dialog box. Click Uninstall Driver. Delete the drivers before uninstalling the hardware; otherwise, the device won’t appear in the Device Manager’s list of installed devices.

![]() For details about the Device Manager, see “Device Manager,” p. 612.

For details about the Device Manager, see “Device Manager,” p. 612.

Tip

![]()

If a USB controller doesn’t install properly, especially if the controller doesn’t show up in the Device Manager, the problem might lie in your system BIOS. Most BIOSs include a setting to enable or disable USB ports. Shut down and restart. Do whatever your computer requires for you to check BIOS settings during system startup (usually pressing the Del or Esc key from the initial boot screen). Then, enter BIOS setup and enable USB support.

When that is done, if a USB controller still doesn’t appear in the Device Manager, it’s possible the computer’s BIOS might be outdated. Check with the computer or motherboard manufacturer for an update that supports USB under Windows 7.

Installing and Using Multiple Monitors

Chapter 23 discussed briefly the procedure for setting up multiple monitors. In this section, we explain a few of the more convoluted details and issues that can occur when installing additional monitors.

As you know, Windows 7 supports multiple monitors, a great feature first developed for Windows 98. You can run up to ten monitors with Windows 7, but normally, you will use no more than two or three. Using multiple monitors lets you view a large amount of information at a glance. Use one screen for video editing, web design, or graphics and another for toolbars. Leave a web or email display up at all times while you use another monitor for current tasks. Stretch huge spreadsheets across both screens.

Here are some rules and tips about using multiple monitors:

• Some laptops support attaching an external monitor and can display different views on the internal LCD screen and on the external monitor. This feature is called DualView, and if your laptop supports it, your user’s manual will show you how to enable it. You can ignore this section’s instructions on installing a device adapter and just follow the instructions to set Display properties to use a second monitor.

• Because most computers have no more than one or two PCI slots open, if you want to max out your video system, look into one of the multimonitor video cards available from Matrox, ATI, and various other vendors. From a single slot, you can drive four monitors with these cards. With only two slots, you can drive four to eight monitors. Multimonitor video cards are available for both AGP and PCI slots. Today, most modern graphics cards will drive two monitors without requiring additional hardware of any kind.

• The latest video interface kid on the block, dubbed PCI Express (PCIe) will be at the center of PC graphics for the foreseeable future. The old video champ, AGP, is on its way out. PCIe offers double the bandwidth of AGP 8x. PCI Express X16 slots have peak bandwidth levels of 4.0 GBps (up to 8.0 GBps bidirectional), compared to 2.1 GBps for AGP 8x. PCIe usually support two displays, but some quad-link versions that support four displays are also available. Look for one (be sure your system can accept it) if high performance (such as video or high-end production work) is your aim.

• Many multimonitor arrangements consist of two cards. Today, that usually means dual PCI-e graphics cards.

• If you mix AGP and PCI, older BIOSs sometimes have a strange habit of forcing one or the other to become the “primary” display. This is the display that Windows first boots on and the one you use to log on. You might be annoyed if your better monitor or better card isn’t the primary display, because most programs are initially displayed on the primary monitor when you launch them. Therefore, you might want to flash upgrade your BIOS if the maker of your computer or motherboard indicates that an upgrade will improve multimonitor support on your computer by letting you decide which monitor or card should be the primary display.

• Upon connecting a second monitor, you should be prompted with a dialog box that asks you whether you want to use a mirror arrangement or an extended desktop arrangement. With some luck, this wizard will be all you need to fiddle with. If not and you’re unhappy with the default choice of primary display, you can adjust it with Display properties once both displays are running.

• If you update an older system to Windows 7, the OS always needs a VGA device, which becomes the primary display. The BIOS detects the VGA device based on slot order, unless the BIOS offers an option to choose which device to treat as the VGA device. Check your BIOS settings to see whether any special settings might affect multimonitor displays, such as whether the AGP or PCI card defaults to primary, or the PCI slot order. Slot 1 is usually the slot nearest the power supply connector.

• The design of the card itself, not the monitor, enables it to operate with multiple monitors on Windows 7. Don’t expect any vendors to add multimonitor support simply by implementing a driver update. Either a card supports multiple monitors or it doesn’t.

• Most laptops these days support mirror and extended view modes. How well they do depends on their video card and the amount of video RAM. Note: There is a key combo on most laptops that turns the output to the external monitor off or on. Typically, it is the FN key (lower-left corner of the keyboard) combined with another key such as F4 or F5. Look closely at the little icons on your laptop’s keytops. You may have to press a combination a few times to get to the desired setup (such as laptop screen on and external screen on, or just one screen on).

Tip

![]()

Microsoft doesn’t provide many specifics about which video cards/chipsets work in multimonitor mode, perhaps because BIOS and motherboard issues affect the results different users obtain from the same video cards. The Realtime Soft website contains a searchable database of thousands of working combinations and links to other multimonitor resources, including Realtime Soft’s own UltraMon multimonitor utility. Check it out at www.realtimesoft.com/multimon.

• On older motherboards with onboard I/O such as sound, modem, and LAN, you may have difficulties with multimonitor configurations, especially if devices share an IRQ with a particular PCI slot. You might want to disable any onboard devices you’re not using, to free up resources for additional video cards to use instead.

• Just because a set of cards supports multimonitoring under a previous version of Windows (even Windows XP) doesn’t mean it works under Windows 7. Windows 7 has stricter hardware requirements as part of its strategy to increase reliability (that said, if it works with Vista it probably also works with Windows 7).

These steps detail a likely installation scenario for a secondary display adapter for use with multiple monitors. It’s possible that it will be much simpler for your system. I have included details step by step mostly for those who run Windows 7 on older systems and add a second display card. With newer systems, such as laptops with dual-monitor video display chipsets, you simply plug in an external monitor and turn it on, Windows detects it, walks you through a wizard, and you’re done.

1. Boot up your system into Windows 7, and plug in the second monitor. Or you can right-click a blank area of your desktop. From the resulting pop-up menu, select Properties.

2. Go to the Settings tab. Confirm that your primary display adapter is listed correctly. (That is, if you have an ATI Rage Pro, ATI Rage Pro should be listed under Display.) Your display adapter should not be listed as plain-old “VGA,” or multimonitoring will not work. If this is the case, you need to find and install correct Windows 7 drivers or consult your graphics card manufacturer’s website.

3. After you confirm that the right drivers are loaded for your display adapter and that you are in a compatible color depth, shut down and then power off your system.

4. Disconnect the power cable leading to the back of your system and remove the case cover. Confirm that you have an available PCI slot. Before inserting your secondary display adapter, disable its VGA mode, if necessary, by adjusting a jumper block or DIP switch on the card. Newer cards use the software driver or BIOS settings to enable or disable VGA mode.

5. Insert your secondary display adapter, secure it properly with a screw, reassemble your system, and reconnect the power. Next, connect a second monitor to the secondary display adapter.

6. Turn on both the monitors and power up the system. Allow the system to boot into Windows 7.

7. After you log in, Windows 7 detects your new display adapter and may bring up the Add New Hardware Wizard. Confirm that it detects the correct display adapter and, when prompted, tell Windows 7 to search for a suitable driver. Then click Next.

8. Windows 7 then finds information on the display adapter. When you are prompted, insert your Windows 7 installation CD, or browse to the driver file for your adapter, and click OK.

9. Windows 7 then copies files. When the process is completed, click Finish. Windows 7 then also detects your secondary monitor (if it is a PnP monitor). When prompted, click Finish again.

Note

![]()

All this detection may occur without intervention on your part, and a balloon may appear on the taskbar announcing that your new hardware is ready to be used.

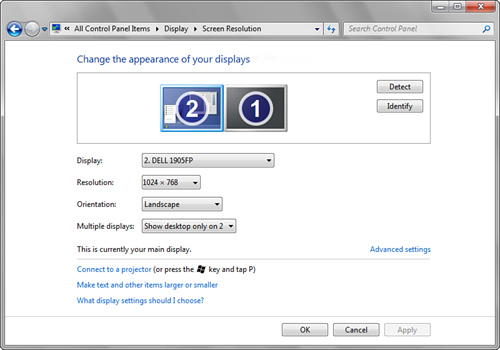

10. After all appropriate drivers are installed, and your secondary monitor is connected and turned on, a wizard should pop up asking how you want to use the newly connected monitor: either as a mirror (repeating what is on the primary monitor) or for an extended desktop area (meaning you can move your mouse across both monitors). Answer accordingly. If you don’t see the wizard, right-click a blank portion of your desktop and select Personalize. Then choose Display. You will notice that two Monitor icons now appear in the center window of the display applet, representing your two monitors (see Figure 27.3). Click the Monitor icon labeled 2, and it becomes highlighted in blue.

Figure 27.3 A system running dual monitors.

11. Under the Change the Appearance of Your Displays heading, your secondary display should be visible. In the Multiple Displays pull-down list, select Extend These Displays, and then click Apply. Click Keep Changes to make this change permanent.

12. While the Monitor icon labeled 2 is highlighted, you adjust the resolution and orientation for the new monitor.

Note

![]()

You can set up Windows 7 with more than one secondary display, up to a maximum of nine additional displays. To do so, just select another supported secondary display adapter with VGA disabled and repeat the preceding steps with another monitor attached to the additional secondary adapter, or attach more than one monitor to either (or both) of your display adapters.

13. To change the way your monitors are positioned, click and drag the Monitor icons around. (Note that displays must touch along one edge.) When you find a desirable position, release the mouse button, and then click Apply, and the Monitor icon is aligned adjacent to the other Monitor icon. Also note that wherever the two displays meet is the location your mouse cursor can pass from one display to the next. That’s why a horizontal alignment is preferred for a standard desktop arrangement (see Figure 27.3).

After you finish these steps, you can drag items across your screen onto alternate monitors. Better yet, you can resize a window to stretch it across more than one monitor. Things get a little weird at the gap, though. You have to get used to the idea of the mouse cursor jumping from one screen into the next.

Tip

![]()

If you’re not sure which monitor is which, click the Identify button, shown in Figure 27.3, to display a large number on all screens.

Installing a UPS

Although Windows 7 contains a backup utility you can use to protect your data, and you may use a network drive that’s backed up every night for your data, or a mirror drive, blackouts and power outages (and the data loss they cause) can happen anywhere, any time. In addition to regular backups, in mission-critical settings, you should be concerned about keeping power going to your PC during its normal operation.

![]() Managing backups is discussed in the section “The All New Backup and Restore” p. 863. “Backing Up the Registry” is covered on p. 809.

Managing backups is discussed in the section “The All New Backup and Restore” p. 863. “Backing Up the Registry” is covered on p. 809.

Tip

![]()

If you don’t have enough open slots to install all extra adapter(s) needed for multiple monitors, look into quad-link video adapter cards that support four monitors (most modern cards support two these days). You can also buy USB monitor adapters if you prefer.

A battery backup unit (also called a UPS, which is short for uninterruptible power supply) provides battery power to your system for as long as an hour, which is more than enough time for you to save your data and shut down your system. A UPS plugs into the wall (and can act as a surge suppressor), and your computer and monitor plug in to outlets on the rear of the UPS.

Electronic circuitry in the UPS continually monitors AC line voltage; should that voltage rise above or dip below predefined limits or fail entirely, the UPS takes over, powering the computer with its built-in battery and cutting off the computer from the AC wall outlet.

As you might imagine, preventing data loss requires the system’s response time to be very fast. As soon as AC power gets flaky, the UPS has to take over within a few milliseconds, at most. Many (but not all) UPS models feature a serial (COM) or USB cable, which attaches to an appropriate port on your system. This cable sends signals to your computer to inform it when the battery backup has taken over and tells it to start the shutdown process; some units may also broadcast a warning message over the network to other computers. Such units are often called intelligent UPSs.

Tip

![]()

If the UPS you purchase (or already own) doesn’t come with Windows 7–specific drivers for shutdown and warning features, contact the vendor for a software update.

Windows 2000 and XP had a function called Windows 2000 UPS Services. This was a service that monitored a serial port for a warning signal from a UPS. If the UPS signaled that a power irregularity had occurred and power was about to go down, an event or series of events could be triggered. Typical events were such things as running a program or sending out an alert to all users or admins on a server about impending doom. The message could alert users to save their work and power down their computers, for example.

Well, this service was removed in Windows Vista, and is likewise missing in Windows 7. What we have now is effectively what laptop computers have—a power profile that includes battery settings. It’s not different—it just works on a desktop PC. You can read about laptop power profiles in Chapter 35, “Hitting the Road,” but I tell you a little about how to drill down into the power management settings here. Then later in this chapter (“Choosing a UPS” and “Installing and Configuring UPS”), you can find some tips to ponder when purchasing or setting up a UPS.

If your UPS doesn’t have provisions for automatic shutdown, its alarm will notify you when the power fails. Shut down the computer yourself after saving any open files, grab a flashlight, and relax until the power comes back on.

Ideally, all workstations assigned to serious tasks (what work isn’t serious?) should have UPS protection of some kind. Although it’s true that well-designed programs such as Microsoft Office have autobackup options that help to restore files in progress if the power goes out, they are not always reliable. Crashes and weird performance of applications and OSs are enough to worry about, without adding power losses to the mix. And if power fails during a disk write, you might have a rude awakening, because the hard disk’s file system could be corrupted, which is far worse than losing a file or two. Luckily, with NTFS and previous versions (see the section “Recovering Previous Versions of a File” in Chapter 31) and other Windows 7 hard disk features, this is less of a specter than it used to be, but still....

My advice is that you guard against power outages, power spikes, and line noise, at all reasonable cost. With the ever-increasing power and plummeting cost of notebook computers, one of the most economically sensible solutions is to purchase notebook computers instead of desktop computers, especially for users who change locations frequently. They take up little space, are easier to configure because the hardware complement cannot be easily altered, and have UPSs built in. When the power fails, the battery takes over.

Tip

![]()

When using laptops, be sure your batteries are working. Over time, they can lose their capacity to hold a charge. You should cycle them once in a while to see how long they last. If necessary, replace them. Also, set up the power options on all laptops to save to disk (hibernate) in case of impending power loss. You’ll typically want to set hibernation to kick in when 5% to 10% of battery power remains, to ensure that the hard disk can start up (if sleeping) and write system state onto disk.

If you use Windows 7 systems as servers, you’ll certainly want UPS support on those, as discussed in Part V of this book. In place of Windows 2000 UPS Services mentioned previously, today’s USB-based UPS systems often come with proprietary programs that sit on top of the capable innards of the built-in Windows 7 event monitor and can work all kinds of magic, signaling users, broadcasting messages about problems or status, and so on, as the battery begins to run down. Users can be warned to save their work and shut down (assuming they are running on a power source that is also functional, of course).

In addition to protecting your hardware investment from the ravages of lightning storms and line spikes, a UPS confers the added advantage of alerting a remote administrator of impending server or workstation shutdowns so that appropriate measures can be taken.

Choosing a UPS

Before shelling out any hard-earned dough for UPS systems, check to see which ones work with Windows 7. Consult the Windows Logo’d Products List on the Microsoft site. Also, consider these questions:

• Do you want a separate UPS for every workstation, or one larger UPS that can power a number of computers from a single location?

• Which kind of UPS do you need? There are three levels of UPS: standby, line interactive, and online. Standby is the cheapest. The power to the computer comes from the AC line just as it normally does, but if the power drops or sags, the batteries take over. There is typically a surge protector filter in the circuit to protect your computer. Line interactive UPS units can handle temporary voltage sags without sapping the batteries, using clever electronics to stabilize voltage levels. This keeps your batteries topped up and ready in case of an outage. Online UPS systems constantly convert AC to DC, filter and clean up the signal, and then convert it back to AC. The result is super-clean power without spikes or sags. Batteries take over, of course, immediately in all three types, if there is a power loss.

• What UPS capacity does each computer need? The answer depends on the power draw of the computer itself, the size of the monitor, and whether you want peripherals to run off the battery, too. To protect your network fully, you should also install a UPS on network devices such as routers, hubs, bridges, modems, telephones, printers, and other network equipment. Check the real-world specs for the UPS. Its capacity is also determined by how long you want the UPS to operate after a complete power outage. If you just want enough time for you or another user to save work, a relatively small UPS will do. If you want to get through a day’s work doing stock trades, you’ll need a hefty unit. UPS units are rated in VA (volt-amperes) and watts. You should either measure your equipment’s actual power draw or select a UPS with a wattage rating that significantly exceeds the wattage rating on your gear. You’ll also want to know how long the UPSs can run at the wattage your system draws. Read the vendor’s battery life specifications carefully, and consider the typical length for power outages in your area. Also, compare warranties on units. You will have to replace the batteries every couple of years. How expensive is that? Are the batteries user replaceable?

Tip

![]()

Network hardware and modems should be powered by the UPS, but printers should not. Laser printers, in particular, draw so much power that the actual runtime for a given UPS unit will be just a fraction of what it would be if the laser printer were left out of the UPS circuit. Because systems can store print jobs as temporary files until a printer is available to take them, there’s no need to waste precious battery power to keep a printer running through a blackout.

• Get a unit with an alarm: You want one that is smart enough to interact with a PC and network to emit alerts or other messages.

• What software support do you want? Do you need to keep a log of UPS activity during the day for later analysis? What about utilities that test the UPS on a regular basis to ensure it’s working?

Installing and Configuring a UPS

If you plan to use a UPS that doesn’t support signaling to the computer via a data cable, you needn’t worry about the following settings because they won’t make any difference. Simply plug your PC into the UPS and then plug the UPS into a wall outlet. Do your work at the computer. One day you’ll notice that all lights in the room go off, but the computer stays on. That’s your moment of grace. Save your work and shut down or hibernate the PC.

If your UPS is smarter (and it should be), simply install it according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Typically, you connect the UPS to the power source, the computer to the UPS, and the USB between the UPS and the computer. After successful installation, you’ll have a battery icon in your system tray near the clock, just like on a laptop.

Caution

![]()

If by chance your UPS is a serial-cable unit, be aware that normal serial cables do not work to connect a UPS to a Windows 7 machine. UPS serial cables, even between models from the same manufacturer, use different pin assignments. It’s best to use the cable supplied by the UPS maker.

Now all you have to do is tell your system what to do during various cases of battery failure. Your system will constantly monitor the condition of the battery, just as a laptop does. So, if the AC power fails, presumably the UPS switches on, and your PC keeps running. Then, the power profile you use comes into play. Here’s how to fine-tune your profile:

1. Click Start, Control Panel, Hardware and Sound, Power Options.

2. Under Select a Power Plan, choose the power plan you want. Under that plan, click Change Plan Settings.

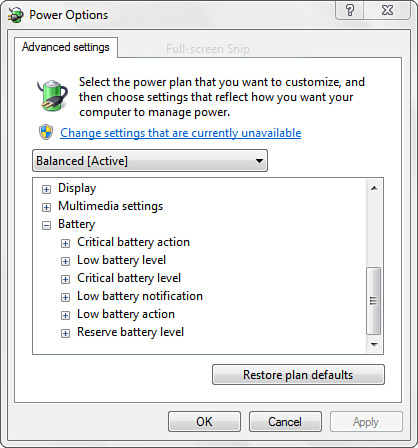

3. In the next dialog box, click Change Advanced Power Settings. You’ll see the dialog box shown in Figure 27.4.

Figure 27.4 Here you can set the UPS and system behavior for cases of power outage.

4. Click the + next to the Low Battery Action and the Critical Battery Action and set what you want your PC to do when the power gets low. I suggest Hibernate, not Sleep, because Sleep will keep only your data intact as long as battery power is available. Shut Down is the next best option, but not very good, because if you are not present, unsaved work may be lost when the system shuts down.

5. Set the Low Battery Notification to On for both Plugged In and On Battery. This way, if the battery level is getting low (perhaps due to a worn-out or defective battery), you’ll be notified.

6. Set the Low Battery Action for Plugged In, too, to be extra cautious. For example, you might want the computer to notify you that the power is low and then hibernate or shut down.

7. Set the Low Battery Level and the Critical Battery Level after considering your computer’s power needs and the capacity of your power supply. I like to play it safe and set Critical to 10% and have the computer hibernate at that point. Then I can wait out the blackout, replace the UPS or battery if necessary, and start back up right where I left off. It takes a few minutes to hibernate sometimes, so make sure you have enough energy in your battery to keep everything working during the wind-down.

Testing Your UPS Configuration

Testing your UPS configuration from time to time is wise, to make sure you aren’t left powerless when a real emergency occurs. Follow these steps:

1. Close any open documents or programs.

2. Simulate a power failure by disconnecting the power to the UPS device. After disconnecting the power to the UPS device, check that the computer and peripherals connected to the UPS device continue operating and a warning message appears onscreen.

3. Wait until the UPS battery reaches a low level, at which point a system shutdown should occur.

4. Restore power to the UPS device.

How Do Upgrades Affect a Windows 7 License?

When you install any version of Windows, you must click to approve its End User Licensing Agreement (EULA). Though most people breeze right past this step, the EULA is a legal and binding contract between you and Microsoft. When you sign (or click) the EULA while installing Windows 7, and when your copy of Windows 7 is activated online, a snapshot of your computer system is made (no personal data is recorded, Microsoft claims) and sent to Microsoft to identify your system, matching it with the unique serial number encoded in that particular copy of the software.

Code internal to Windows 7 that you never see unless there is trouble, called Software Protection Platform (SPP), checks your system for authenticity of Microsoft software and alerts Microsoft if it finds inauthentic (pirated) software. SPP’s purpose is to help Microsoft crack down on software privacy, and (they say) to help protect you by ensuring that your Microsoft product is authentic. SPP can get upset and nag you if it detects pirated software or other EULA infractions.

In Vista, this capability was branded Windows Genuine Advantage (WGA). In Windows 7 this facility is renamed Windows Activation Technology (WAT). Whereas the first major version of Vista (before Service Pack 1 was released) could actually cripple the OS if it wasn’t activated or if indications of piracy were found, subsequent versions of WGA lost this capability, and replaced it with a “nag facility” that sets your screen background to black and nags you to get right with Microsoft, and does so every hour on the hour until you fix the problem (which usually means supplying a valid license key obtained from Microsoft in some form or fashion).

The upshot of WAT (and the WGA technology that remains in synch with that from Vista SP1) is exactly this:

• If you buy a PC with Windows 7 already installed, you have fewer rights of reinstallation. You are not supposed to move Windows over to another machine, and it would be difficult to do so because you typically don’t have an install DVD anyway.

• Retail copies of Windows cost much more than OEM copies, for a reason. You can move them around between computers as you upgrade to better machines. If you buy a full retail version, you can put it on another computer and reactivate the new one. Keep in mind, however, that this is legal only if you uninstall it from the previous computer. You are supposed to format the system hard disk in the old computer. Microsoft should give you an uninstall utility so you don’t have to wipe the hard disk, but they don’t. Personally, I think this is because they don’t really expect the average small business or home user to do this. Microsoft is simply trying to prevent a PC clone manufacturer from duplicating one copy of Windows on hundreds or thousands of PCs.

Upgrading Hardware in the Same Box and Complying with EULA

Because this chapter deals with upgrading hardware rather than complete computer replacement, the real question is: How do EULA and SPP rules apply to upgrades? How much hardware can you upgrade before SPP starts nagging you through the WAT facility?

In the original version of Windows Vista, SPP worked this way: The hardware in your system was recorded when you activated Windows, as already mentioned. If you changed too many items (most notably, your motherboard and hard disk drive), system functionality was slowly reduced. Over time, portions of the OS were crippled and you’d be running in Reduced Functionality Mode (RFM). At first, there would only be subtle events, such as updates or Aero not working, but eventually the desktop would go black, Windows Explorer wouldn’t work, and all you could do is browse the Internet.

Thankfully, this is no longer the case. Because of WAT and a kinder, gentler approach to dealing with activation or potential piracy, you’ll simply have to put up with hourly nag sessions and a black desktop background.

What triggers the need to reactivate Windows? As intended, each hardware component gets a relative weight, and from that WGA determines whether your copy of Windows 7 needs reactivation. The weight and the number of changes is apparently a guarded secret. If you upgrade too much at once, WAT decides that your PC is new, and things can get messy.

The actual algorithm that Microsoft uses is not disclosed, but we do know the weighting of components is as follows, from highest to lowest:

1. Motherboard (and CPU)

2. Hard drive

3. Network interface card (NIC)

4. Graphics card

5. RAM

If you just add a new hard disk or add new RAM, there is no issue. If you create an image of your Windows 7 installation on another hard disk and swap that hard disk into the system and boot from it, or if you replace all your RAM and reboot, WAT gets triggered and checks to see whether you must reactivate Windows 7.

In theory, chances that you’ll get stung by any of this are not great. It was widely expected that the only users who’d need to worry about reactivation would be users who’d buy a preinstalled system, image the hard disk or try to move the hard disk to a newer, faster computer, or perform a motherboard upgrade using a preinstalled copy of Windows 7.

Unfortunately, in practice users have been forced to reactivate after relatively modest hardware changes. In one Vista example, a user who changed from a DirectX 9– to a DirectX 10–compatible graphics card had to reactivate his installation. But wait, it got worse: Another Vista user had to reactivate Windows after upgrading to a newer version of the Intel Matrix Storage driver for his motherboard. Essentially, WGA mistook a driver upgrade for a significant hardware upgrade. Users who missed the three-day reactivation window (it’s easy to do) found themselves needing to make a phone call to reactivate. Users who were hearing-impaired found that difficult to do.

Meanwhile, users of bogus Windows 7 and Vista copies have used activation bypasses such as the Grace Timer or OEM BIOS exploits to run Windows without interference from WAT (WGA in Vista). Essentially, in the original version of Windows Vista, Windows made it way too difficult for legitimate users to cope with systems that could not be activated normally or needed to be reactivated. This led to the proliferation of usable (but illegal) workarounds. Thankfully, WAT brings those days to an end, as SP1 did for Vista.

Upgrading and Optimizing Your Computer

Here are several tips I’ve learned over the years that can help save you hours of hardware headaches.

Note

![]()

Some “legacy” hardware technologies no longer supported include EISA buses, game ports, Roland MPU-401 MIDI interface, AMD K6/2+ Mobile Processors, Mobile Pentium II, and Mobile Pentium III SpeedStep. ISAPnP (ISA Plug and Play) is disabled by default. Startup Hardware Profiles also have been removed.

Keep an Eye on Hardware Compatibility

If you’ve been accustomed to thumbing your nose at Microsoft’s Hardware Compatibility List (HCL)—renamed Windows Logo’d Products List for Windows 7—because you’ve been using Windows 9x, it’s time to reform your behavior. In a pinch, Windows 9x could use older Windows drivers and could even load MS-DOS device drivers to make older hardware work correctly. Windows 7, like other NT-based versions of Windows, has done away with AUTOEXEC.BAT and CONFIG.SYS, so you can’t use DOS-based drivers anymore. And, although Windows 7 can use some Windows 2000 and XP drivers in an emergency, you’re much better off with drivers made especially for Windows 7 or Vista. You can view the online version of the Windows Logo’d Products List by visiting the Microsoft website.

Tip

![]()

Hardware failures, power failures, and human error can prevent Windows 7 from starting successfully. Recovery is easier if you know the configuration of each computer and its history and if you back up critical system files before tweaking your Windows 7 configuration.

A good hedge against this problem is to create a technical reference library for all your hardware and software documentation. Your reference library should include the history of software changes and upgrades for each machine, as well as hardware settings like those described here.

Sleuthing Out Conflicts

When you’re hunting down potential IRQ, memory, and I/O conflicts, use the Device Manager to help out. Yes, Computer Management, System Information, Hardware Resources, and Conflicts Sharing can show you potential conflicts, so those are good places to look, too. But let me share a trick that you can use with the Device Manager that isn’t readily apparent.

Normally, the class of devices called Hidden Devices isn’t shown. To show them, open the Device Manager (either via Control Panel, System, or from Computer Management). Then, on the View menu, click Show Hidden Devices. A checkmark next to Show Hidden Devices indicates that hidden devices are showing. Click it again to clear the checkmark. Hidden devices include non-PnP devices (devices with older Windows 2000 device drivers) and devices that have been physically removed from the computer but have not had their drivers uninstalled.

Optimizing Your Computer for Windows 7

Optimizing your computer for Windows 7 is actually quite easy. I’m very impressed with the capability of this OS to keep on chugging. It doesn’t cough or die easily if you mind your manners.

• If you buy new stuff for an upgrade, consider only hardware that’s on the tested products list and the Windows Logo’d Products List (https://winqual.microsoft.com/hcl/).

• When you buy a new machine, get it with Windows 7 preinstalled and from a reputable maker with decent technical support, not just a reputable dealer. The dealer might not be able to solve complex technical problems. Brand-name manufacturers such as Dell, HP, Gateway, Lenovo, Acer, MSI, and so on have teams of engineers devoted to testing new OSs and ironing out kinks in their hardware, with help from engineers at Microsoft.

• If you love to upgrade and experiment, more power to you. I used to build PCs from scratch, even soldering them together from parts. Then again, you can also build your own car. (I used to just about do that myself, too.) Or you can buy it preassembled from some company in Detroit or Japan. It really isn’t worth spending much time fiddling with PC hardware unless you assemble systems for some specific purpose. Given amazingly low prices for computers these days, don’t waste your time. And don’t cut corners in configuring a new machine, either. For an extra $50, you can get goodies such as a modem, network card, and faster video card thrown in. Add more bells and whistles up front and save yourself some hassle down the road.

• Run Windows Update frequently or set it to run itself.

• Schedule hard disk defragmentation (see Chapter 24) and make sure you have a decent amount of free space on your drives, especially your boot drive. Remember that Windows 7’s defragmenter requires at least 15% empty space on each drive you want to defragment.

• Get an extra external hard disk of equal size or larger than your computer’s internal hard disk. Use an automated backup program, such as the File and Folder Backup built into Windows 7, to automatically back up your important stuff on a frequent basis. (Mine runs every night.) Disks are cheap these days, and your time, contacts lists, emails, and documents are valuable!