Using Technology

It seems any mention of technology is obsolete before you finish reading the sentence. However, you should be aware of some generalities when you use different devices, especially from a technical perspective. As a visual presenter, you should be adept at using different pieces of equipment, although you will probably get comfortable using one particular device for most of your presentation needs.

Handling Projectors

If you recall, Chapter 23, “The Media—Designing Visual Support,” covered the cost, convenience, and continuity issues related to overheads, 35mm slides, and electronic images. The traditional devices—overhead and slide projectors—are not difficult to work with from an operational standpoint. Typically, the big technical question is “How do you turn this thing on?” For electronic presentations, you have to know a bit more than the on/off switch when you work with the current crop of LCD (liquid crystal display) projectors.

→ For more information about projectors, see “Understanding Media Types” in Chapter 23.

First the good news: These devices are getting easier and easier to set up, but until personal computers are a cinch to work with, these electronic projectors will carry a bit of intimidation along with them. Don't worry. If you haven't used one, chances are someone is available who has.

I don't want to get into a long list of specifications, except to tell you that the LCD projector connects directly to your PC. Depending on the features of your PC, the projected image may or may not need to be adjusted.

Brightness

The brightness of the image is a big issue when you can't control the lighting in the room. You'll probably hear the word lumens when people talk of a projector's brightness. Lumens is a measure of brightness. The more lumens, the brighter the image. There's more to it than that, but that's why there are professionals who sell these things. Audiovisual companies (A/V dealers) are excellent sources for learning more about the unique features and benefits of electronic projectors.

In a room with only fluorescent lights, go for a projector with at least 500 lumens so that your image remains visible, even with the light spilling onto the screen. Of course, if you have less light hitting the screen, the image will look even better.

Resolution

Think of resolution as the quality of the image. I like to use the comparison of a chain link fence, some chicken wire, and a screen on a door. The sizes of the holes are different in each. If you took a paint brush and painted the word “resolution” on the fence, the wire, and the screen, which would be easiest to read? It would be the screen, because the holes are closer and smaller, making the letters in the painted word appear less broken up and of higher quality. If you hear of 640 × 480 resolution, that's the chain link fence. 800 × 600 resolution is the chicken wire, and 1,024 × 768 is the screen door. The higher the resolution, the closer the holes, and the better the quality of the image, because the pixels, the little dots that make up the image, are closer together.

Portability

Naturally, if you don't have to carry anything to the presentation but your PC, then you don't need to be concerned about the portability of the projector. Such devices are getting lighter—most are around 10 pounds, and some are as light as 5 pounds. The benefit of bringing the device with you is that you can be confident of the image you will get. If you carry the light source to the event, you have more control of the display. I have made plenty of presentations when I did not have the quality image I was used to and had to overcompensate on my delivery to make up for the poorer image. A lighter projector means more likelihood of your taking it with you to the event.

Multiple Connections

Having options for more than one input and output is helpful, especially if you plan to use a variety of media, including video and audio. Some projectors even allow hookups for two computer sources. This can be helpful in an event with more than one presenter, each of whom has his own PC. The capability to connect a VCR, a video camera, or other device can add value and flexibility as well. In my full-day “Presenting Made Easy” seminar, I use my computer and play a videotape as well, using the same projector by simply switching sources when needed. Typically, to switch between different inputs, a press of a button on the projector is all that's required.

Note

When a projector enables multiple sources, it usually lets you set up each source independently. For example, when I switch from my PC to my video source, the video settings on the projector change. I can control volume, brightness, contrast, and so forth separately for each input because they are usually different.

Of course, not every piece of equipment works perfectly when connected to another piece of equipment, as may happen with some projector-to-computer hookups. Sometimes, one person's notebook PC works fine with a projector, but the next person's PC does not for a variety of reasons. Changing the settings on projectors varies among models and types, so it is best to arrive at your presentation early enough to make sure that everything works properly.

The worst moment in the world is when you start playing with menu options on the projector two minutes before the show is supposed to begin.

Many projectors have multiple outputs, as well. Outputs for video and audio can be valuable when presenting. For example, if you plan to use sound during your presentation, having an external audio feature on the projector is very helpful. When you have a larger group of people, the tiny speakers of a projector can't disperse sound evenly to everyone in the room. It sounds louder for those who sit closer. In some places such as in a hotel, you can connect the projector to the sound system used for your microphone, which is typically connected through the speakers in the ceiling. House sound, as it is called, distributes the audio evenly to the audience.

Working with Laptop Presentations

Chances are, if you use an electronic projector, you are probably connecting a laptop or notebook computer to it. You'll have some limitations with laptop systems, but I don't want to get too technical on the subject. The good news is that the laptop is a fully functioning office, complete with backup information and tons of other stuff, literally at your fingertips. You need to know a few things about computers and projectors, especially when it comes to laptop presentations.

Remote Control

No one who stands in front of a group of people should advance a PowerPoint presentation with the keyboard when a remote control offers you incredible freedom of movement and enhances your presentation skills accordingly. Consider using a two-button remote control that can advance your visuals while you stand inside your triangle and present.

Pro PresenterMany types of remotes are available on the market right now, and although I normally avoid endorsing products, I've got to say that I've been using the same remote control for years. It's the perfect device for delivering linear electronic presentations. In fact, when I coach people, they are using it within seconds—that's how easy it is to control. It's called the Pro Presenter. It's a flat, infrared wireless, handheld remote control for the PC or the Macintosh. The remote can be used with or without its software. It's the same size as a credit card, it fits snugly into the palm of your hand, and it operates from up to 35 feet away from your computer. It's a $99 wonder that frees you from ever touching the computer while you present. At the risk of sounding like I'm selling you something, visit MediaNet's Web site (http://www.medianet-ny.com) to learn more about this little product, which is manufactured by Varatouch Technology of California (http://www.varatouch.com). |

Some remotes also have the capability to control the mouse pointer, as well. It's like having the left and right mouse buttons and the pointer all in your hand at the same time. The only thing to worry about is accidentally moving the mouse pointer while you present.

Some remotes work on an RF (radio frequency) signal rather than infrared. This means that you don't have to point at the receiver when you advance the visuals. Unfortunately, these remotes tend to be larger. When a remote cannot fit comfortably into the palm of your hand, it becomes more obvious that you are using one.

When you think of the amount of money invested in a computer and a projector—not to mention the presentation and your time to deliver it—the cost of adding a remote control is insignificant. Think of this: An inexpensive key can open the door to a top-of-the-line Chrysler. Buy a remote.

Simultaneous Display

This is a big advantage to any speaker, but particularly to a visual presenter. Think about overheads and slides for a minute. You have to turn your head back toward the screen just to glance at the information. If your visuals are busy, you end up doing this even more often. But a laptop offers you a unique advantage called simultaneous display. The image the audience sees on the big screen appears on the display of your PC at the same time. If this feature is not already set up in your PC, normally you can send the display signal to an auxiliary screen by pressing a combination of keys on your keyboard. On your notebook computer you might see a graphic symbol that looks like a PC and a screen on one of the function keys, usually F5. This is like a toggle that can be set in three positions. One keeps the image on your notebook screen; another sends the image out the VGA (monitor) port on the back and removes it from your notebook screen; the third setting sends the image out the back but leaves it on the notebook screen at the same time. This is called simultaneous display.

It's like a little TelePrompTer, except you don't have any speech to read. In fact, if your visuals are less busy, the text displayed on your notebook screen will be larger and should be readable from however far away from the computer you are standing as you present.

In addition, if you look back to Figure 26.3, you can see how your equipment (computer and projector) is centered in the front of the room. When you glance at your notebook screen, it will appear as though you are making eye contact with the section of the audience sitting beyond the table but still in your line of sight. It takes only a slight shift of your eyes downward to catch the information on the screen. Although some may notice the movement, it certainly is not as obvious as the complete look back to the screen done constantly with overheads and slides.

Depending on your computer and the projector, the simultaneous display option may not be available, however. This is a constantly evolving issue with both the computer and projector manufacturers, but in any case, what you need to be concerned about is this: In most cases, when the resolution of the projector is lower than the resolution setting on your PC, the projector compensates for the higher signal coming from your PC and drops bits of the image. This makes smaller text appear choppy. The solution is to lower the resolution setting on your PC to match the projector. However, with some computers, that's still not enough. You may have to disable the simultaneous display feature so that the projector can project a full and clear image at the lower resolution. This is not always the case, but you'll have to try it to be sure.

On the other hand, if the projector has a higher resolution than the computer, you should have no problem, for the most part, because the projector should be able to handle the lower-resolution signal coming from your computer.

Transitions

Electronic presentations allow the use of transition effects between visuals. Rather than use transitions randomly, you should consider the way the next image will appear to the audience. The most consistent approach is to try to use a transition that matches the eye movement pattern for the upcoming visual, not the current visual. In other words, transition effects are designed for the visual yet to appear, not for the visual already displayed.

For example, let's say you're displaying a text chart with several bullet points, followed by a horizontal bar chart and then a pie chart. You could use a “horizontal blinds” transition into the text chart because the lines of text are separated by horizontal space. Then you might use a “wipe right” transition from the text chart to the bar chart because the eye will be moving from left to right when the bar chart appears. Then, from the bar to the pie chart, a “box out” transition could be used. The circle of the pie centers the eye in the visual, and the transition opens from the center matching the circle.

Check the general geometric shapes in the next visual when planning a transition to assure a consistency in eye movement from one image to the next.

Screensavers, Reminders, and Navigation Issues

One of the things you should do with your laptop is turn off any screensavers you may have. If you stay on one visual too long and your screensaver comes on, it may knock out the signal going to the projector. The audience is left staring at a blue screen. Disable the screensaver in Windows and any timeout functions set in the computer itself. Your PC's diagnostics or setup screen will tell you if any screensavers are enabled.

Some contact-management programs offer reminders, such as alarms, that pop up when a task is due. When you present, don't load software that has task reminders, unless you want the audience to see just who it is you're having dinner with that night.

Finally, under Tools, Options in PowerPoint, select the View tab and make sure all three check boxes in the Slide Show area are unchecked. First, you don't want the pop-up menu to appear on the right mouse click. When you leave this box unchecked, your right mouse button will do what it is supposed to do—navigate the show backward one visual. If you need to navigate to different images or you need to get other help during the presentation, you can simply go to the keyboard and press F1, and the menu of choices will pop up. Second, you don't want the pop-up menu button to show in the corner of each visual as you present. Unless you have a remote mouse, you won't be able to click this transparent icon anyway. Third, you don't want to end your presentation with a blank slide, especially if you've been using a consistent background throughout. Instead, under the Slide Show menu, choose Set Up Show, and check the box Loop Continuously Until “Esc” so that your show loops back to the beginning. This causes your presentation to end with the same image you started with, if you so choose.

Incorporating Multimedia

Nothing you can do with a laptop computer—using animation, sound, video, or any special effects—even comes close to what you see in the movies. We are accustomed to seeing incredible special effects, and we have Spielberg and Lucas to thank for it. No one runs home from a business presentation saying, “Honey, you won't believe this, but at this presentation today—well, I don't know how—but the computer—well, it played music and a voice came out—a real voice!” It's hard to impress people with technology these days.

Although much has been said about multimedia, all I can add is this: Beware of multiMANIA. Multimania is the overuse of technology to the point that the audience is enamored by your special effects but can't remember the plot.

You should be concerned when you think about adding elements in your presentation that go beyond your delivery. For example, playing a video clip during your presentation introduces another character to the audience, another presence—basically, another messenger. This isn't wrong, any more than it's wrong to introduce another presenter. But elements that simulate or mimic real-life forms (speech, movement, real people in action) reach the audience in different ways than traditional visual content.

You need to understand the particulars of animation, sound, and video as unique multimedia elements and their effect on the audience.

Animation

Animation is simply an object in action. However, it should never be text in action. Objects can move, but text should stand still. Take this test. Move this book up and down and try to read it. I rest my case. You can't read moving text until it stops or at least slows down enough for you to anchor on it. Ever try reading the weather warning as it crosses the bottom of your TV? You can't read each word as it appears from the far right; you have to wait for a few words to make it to the far left of the screen so you can anchor and read left to right.

Text should never move. All those transitions you picked with the animated bullet points—out. Just because a programmer can make it happen doesn't mean it's useful. Animated text lines can't be read until they stop. This means the only effect was the animation, the movement. If an action serves only itself, it is useless because the audience takes interest only in the action, not the information. Eventually, people will watch your text flying in from different points and begin to take bets on where the next line will enter from and when.

Note

If the text you are animating is part of a logo or is to be treated as a standalone item, then it is more like an object and probably contains very little of the anchor-and-read requirement. In those cases, you can animate the text object.

Objects can be animated, but apply a sense of logic. Don't have a clip art symbol of an airplane floating from the top of the visual downward. Airplanes don't do that—at least not more than once. Animated bars or moving lines showing a procedure can help the audience understand growth or flow and make the visual come alive to express an idea. Animation is not a bad thing as long as it is not overdone to the point that only the effect is noticed.

Sound

The first sense you experienced was hearing. Before birth you could hear your mom's voice as she carried you from place to place. Sound is one of the most important senses throughout our lives and can dramatically affect our perceptions.

Sound can be either used or abused during a presentation. Typically, you might want to add sound at certain points to highlight a key phrase or to add value to some information.

The main thing is to be consistent with sound. The audience not only looks for anchors; they listen for them as well. Your voice becomes an anchor as people adjust to your volume, pitch, and tone. Other sounds placed in the presentation need justification and sometimes repetition to become anchored. Don't make a noise just because your software program has this great library of sounds that you feel compelled to use.

Sounds linked to elements on the visual are usually ineffective. Examples of these are the cash register sound linked to a symbol of money; the sound of applause signifying achievement; the shutter of a camera each time a photo of a person appears on the visual; and the worst of all sound effects—the typewriter sound linked to animated text and possibly to each letter on each text line. In all these cases, the sounds are one-time effects that can become phony or even obnoxious when repeated.

Don't get me wrong, sound can play a major role in the presentation if done right. Music is a good example of this. The movie Jaws wouldn't be the same without music. The Omen wouldn't be as scary. The nice thing about music, particularly instrumental music, is that you can talk over it, and the audience can blend your words with the background music. In addition, if the music track is long enough or loops continuously, the audience gets the benefit of repetition and will anchor to the music as it plays.

Tip from

Even if you don't incorporate music into the presentation, consider playing some tunes as people are coming into the room or perhaps as they leave.

You don't need to have the music clips stored on the computer; the files can be quite large. You can simply use your computer's CD-ROM drive (if you have one) or bring a portable CD player and connect it directly to the projector.

→ To see how to use sound effectively with the Nostalgia Theory, see “Knowing Particulars of the Audience” in Chapter 22, “The Message—Scripting the Concept.”

For example, let's say you are giving a presentation in 1999 to an audience, the average age of which is 31. That means they were 15 years old in 1983. Michael Jackson's “Beat It” will be a more popular sound clip for this crowd than his 1970 tune “ABC,” when the majority of those in this group were wearing diapers!

You get the idea. Continuity in sound is better than periodic or intermittent sound. You can process continual sound just like listening to the radio while driving a car. Hear a siren or horn beep (intermittent sounds), and your attention is immediately diverted.

Video

Multimedia takes on a very different flavor when you incorporate video. The multimedia issues with video come in two flavors, full-screen and full-motion. The goal is to have both, but the technology you own may not enable either. Full-screen video is easy to envision. The video fills up the whole screen just like a TV. Many video clips in presentations today are half, one-third, or even one-quarter the size of the screen, depending on the computer system used to deliver the video.

Full-motion video is what you get when you watch TV—30 frames per second. That speed is fast enough for the images to appear lifelike, which is why TV is such a powerful medium. Much of the video shown through laptops is not full-motion; it is about half-motion or 15 frames per second. At times, especially during long computer or digitized video clips, you can get synchronization problems with voice and video after a while. That's when the video and voice get out of sync, and it looks like one of those foreign films with poor dubbing.

With most laptops, we sacrifice full-motion and full-screen for the sake of storage and speed. Naturally, the storage required for video is much greater than for still images or even clip art, for that matter. I won't go into the technical details of file sizes, but if you've ever loaded a video clip on your PC, you know that it takes up a lot of disk space. For example, a one-minute clip that plays in a window only half the size of your screen might be about 10 megabytes. Of course, one minute is a long time for a video clip when you consider that TV commercials average 15 to 30 seconds. Storage and speed are issues for video, and you should limit the length of the clips.

The goal is full-screen, full-motion video. Computer speeds are getting faster, so soon this will not be an issue. However, not everyone uses the latest technology, and I suspect it will be a few years before video is a breeze to watch through a PC in a presentation.

Regardless of speed, another issue with video concerns movement and direction. If your video clip is not full-screen, you may be including it as part of a visual. If the visual has text and the video clip shows something moving in one direction, make sure that direction matches the way the text reads. For example, a visual in English would have a left-to-right reading pattern. If your clip shows a car moving from right to left, you'll have an eye movement clash. Try to match the direction whenever possible.

Image Magnification

You may find times when your presence on stage is also reproduced on screen. This might happen if you present in a large venue where people are sitting so far back that they cannot get a good view of you or your expressions. Image magnification can be used to make you visible from a far distance. A separate screen is set up, a camera focuses on you, and the video signal is projected onto the big screen. The good news is that everyone can see you as if they were in the front row.

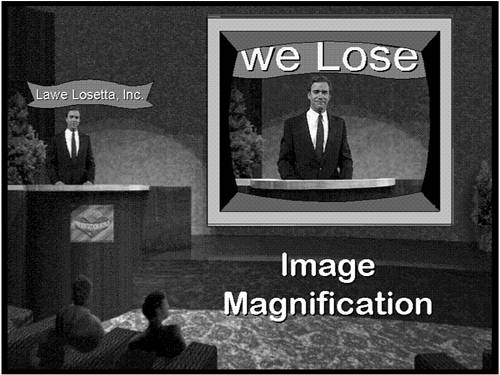

However, some problems can occur. Whenever a camera is used, you should be concerned about what the framed image looks like to the audience. Figure 26.5 shows how different the perspective is when the presenter is viewed from the audience and through the eye of the camera. The banner hanging behind the presenter looks fine when viewed from the audience, but the close-up shot framed by the camera clips some letters from the company name “Lawe Losetta, Inc.,” showing only the last two letters of “Lawe” and the first four letters of “Losetta”; through the camera it reads “we Lose.”

Figure 26.5. Be careful that camera cropping doesn't change your message.

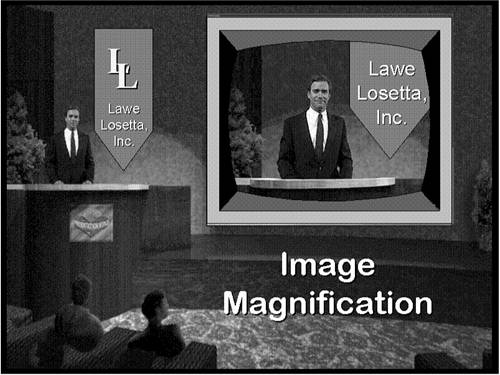

In Figure 26.6, the banner is hung vertically, and the framed image doesn't reveal any surprises. Always check the viewing angle when using a video camera to frame the presenter.

Glitches Happen

It goes without saying that you should practice your presentation. In fact, the more multimedia effects you have planned, the greater the need for a technical run-through before the event. Sometimes (and usually at the worst moments), computers cause problems. Whether the video clip moves in a jerky motion or the sound effect doesn't play or the system just “locks up” for no apparent reason—the thing to remember is not to panic. We have all been there before, and it's not unusual for things to go wrong every so often.

If you know how to fix a problem, then fix it. At the same time, explain to your audience what you are doing. Don't just turn your back and say, “Pay no attention to that man behind the curtain!” The real issue is time. If you can fix it within three minutes, fine. If you think the problem will take longer to fix, give the audience an opportunity to take a short break.

Figure 26.6. Careful positioning helps avoid image magnification problems.

For practice, run your presentation; somewhere in the middle of it, turn off or reset the computer. Time how long it takes to reboot your PC and get it back to the exact spot where you turned it off. If it takes more than three minutes, you'll know to give the audience a short break the instant you know you may have to reboot the computer during your presentation.

Overall, if you keep calm and collected during technical difficulties, you have a better chance of keeping the attention of the audience. Of course, the more command you have of the message and the more effective your delivery skills, the easier it will be for you to overcome any technical problem.

Remember that the technology carries only the speaker's support material. You are the speaker, and your delivery embodies the message. The audience will constantly look to you for guidance and direction. Never forget that you are in control.