Getting Up Close and Personal

The most likely scenario you'll encounter is a presentation to a small group. I find that more than 80% of presentations are given to groups of fewer than 10 people, usually in a conference room setting. Typically, the fear factor is reduced when fewer people are in the room, so these up-close-and-personal situations are easier for most presenters. Perhaps that is what makes small group presentations more common. Another reason is probably scheduling: It's easier to convene a smaller group of people in a local setting than it is to gather a crowd for a larger event.

Regardless of how these situations develop, the common fallacy among presenters is that less formality exists when the group is smaller and people know one another. Be careful: Just because everyone knows one another doesn't mean your presentation has automatic impact. Remember that it gets more and more difficult to impress a person after the first date. When presenting in those informal settings, your skills must be better, especially if you think the formality is unnecessary.

Who can really define just what “formality” means in the context of a presentation? Moreover, who can say which presentations merit formality and which do not? Every presentation is formal in the sense that your skills must be as sharp as ever to make an impact with your message, and your goal is to maintain consistency of style in all presentation settings.

Understanding the Conference Room and U-Shape

In Chapter 26, “Exploring Technicalities and Techniques,” we discussed theater-style and classroom-style seating in relation to the room setup. The traditional conference room offers some important seating opportunities that are a bit different from the others. This is also true of another common room setup, the U shape. Both conference room and U-shape settings share the same seating dynamics. Because many conference room tables are longer than they are wide, most of the people at the table face one another. The same is true with the U shape.

Tip from

Increase the size of your triangle. You can give yourself more room to maneuver in the small group setting by moving or removing some seats. In the conference room, the first and possibly second seat immediately to your right can be eliminated. This makes your triangle longer (from the screen to the first available seat). When you have more space, your movements within the triangle are more distinct, and you can create more impact as you change positions during your presentation.

In a U shape, consider removing the first table on your right (the one closest to you) to create a larger space in which to move. The U shape starts to resemble a J shape when the first table is taken away.

If care is taken to arrange the seating of your “guests” properly, the results of your meeting may be more successful. As the presenter, you have three different audiences: There are people to your far side and your near side, as well as people seated straight ahead of you toward the middle. These three seating areas or positions are referred to as the power, input, and observer seats, respectively. Depending on where people sit, an interesting dynamic may be added to the discussion.

Note

I'm assuming that you are standing to the left of the screen, from an audience perspective. Even without a screen for visual support, you should still anchor to one side, preferably to the left, to maintain the same seating dynamics throughout the talk. Moving around to different sides is not recommended, because it disrupts the original perspectives of those in the audience.

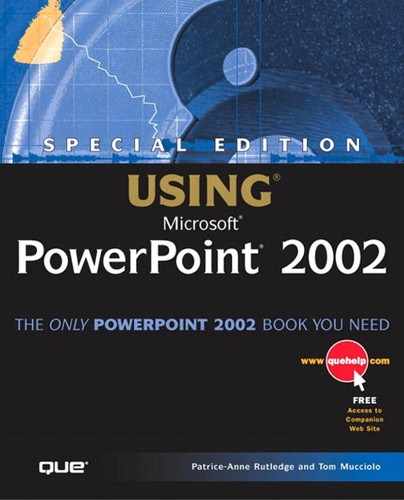

Power Seats

Those who sit diagonally opposite you as you speak are in the power seats. Because these seats mirror the presenter, an implied power is given to those occupying those seats. Figure 27.1 shows the location of the power seats. In a typical conference room or U shape, these seats are grouped in the corner. Depending on the size of the table or the U shape, two or more people may occupy the power seats. Keep in mind that these people assume power whenever they make comments or interact in some way. Even though they are not standing when they speak, the dynamics of the room create the effect of the seating importance to the rest of the group simply because those in the power seats mirror you.

Figure 27.1. From the presenter's view, the power seats are diagonally opposite.

You can take most advantage of your rest and power positions with those occupying the power seats, because people in those seats tend to face you more than they face the other people in the room. In addition, you can stimulate more group interaction by directing your attention and targeting your gestures toward those in the power seats. Your efforts to include those opposite you will automatically spread the interest to either side, thereby including the entire group.

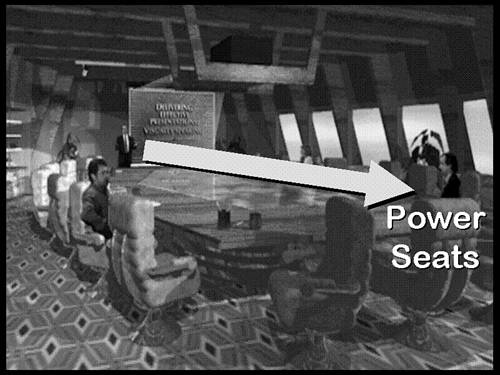

Input Seats

As you present, the input seatsare the ones along the far side of the conference table or U shape. Because you normally stand to the audience's left when you have visual support, the input seats are to your left. Figure 27.2 shows the location of those seats. Those sitting in the input seats have an unobstructed view of you, and they typically interact only when prompted. When they do interact, it is usually to provide input in the form of support information or to offer some type of agreement to a suggestion.

Those occupying the input seats will normally interact more often with the people sitting across from them. The constant challenge of conference room and U-shape seating is that many people in the room are distracted because they can see and interact with one another, which diminishes their attention to you. The input seats still offer a direct view of you and your support visuals (if any). These factors raise the importance of the input seats.

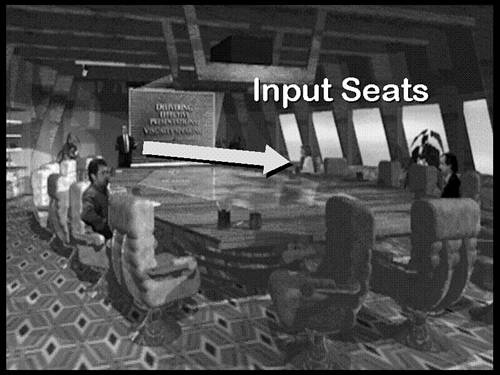

Observer Seats

The people sitting on the near side to you as you present are in the observer seats. Because you normally stand to the audience's left when you have visual support, the observer seats are to your right. Figure 27.3 shows the location of the observer seats. These are the worst seats in the house. People usually have to shift their chairs or lean over just to make eye contact with the presenter. More than likely, the people in these seats will have to give up the convenience of the table to position their chairs to see you as you speak. This means they lose a writing surface to take notes effectively, and they can't reach for the all-important coffee cup without making the effort obvious to the rest of the group.

Figure 27.2. From the presenter's view, the input seats are to the far side.

Figure 27.3. The observer seats are along the near side of the table, from the presenter's viewpoint.

One of the main reasons these seats are referred to as “observer” seats is that the people in these seats tend to spend more time observing the group than they do the presenter. These people have to work harder just to see you in action, and this decreases their attentiveness to your message. If you're going to lose any of your conference room crowd, it will most likely be the observers.

Putting People in Place

It would be great if you could assign seats for people based on the power, input, and observer seating positions. As a meeting comes to order, people usually take seats on a first-come, first-served basis. There are exceptions to this, of course, but for the most part the seating in any presentation is left unplanned. You can balance the scales in your favor, however, by subtly forcing people to take certain seats.

For example, let's say you want to hold one of the power seats for a key person you expect at the presentation. Of course, you have no idea when he will arrive in relation to the others in the meeting. How can you increase the chances that the key person will occupy a power seat?

The strategy is simple, assuming you arrive in the room before anyone else. As soon as you can, place a folder or small stack of your papers on the table, right in front of the power seat that you want to hold from being taken. You could also use a briefcase or jacket on the chair itself, but a chair can be moved out of place more easily.

Then, as people come into the room, be ready to greet them at the door. This helps you spot when the key person approaches. As the room fills, there is less chance anyone will take the power seat you've held, because most people will assume the seat is already taken. People don't like to touch other people's stuff, unless of course no other place is left.

As soon as you greet the key person, you start a conversation as you both move into the room. If you are saying something of real value, the person will naturally follow you to keep listening. You casually meander to the open seat where your folder or papers are resting on the table. Just as you get there, you break the conversation and offer the seat while apologizing for having left your stuff on the table or chair. You also could plan a moment in the discussion when you need to refer to something in the folder. Either way, the excuse to remove your things makes the seat available. As you gather your papers, you pick up the conversation right where you left off, and the person will naturally take the seat as he continues listening.

Note

This is not to suggest that you will be more attentive to only one key person during your presentation. Instead, you must treat everyone the same. The difference is that the key person occupies a seat that offers the best opportunity for attention to your message. This seating strategy plays to your advantage only if you present with the same energy to everyone in the room without singling out any individual.

Seating Your Team and Their Team

Sometimes you may attend a presentation along with one or more people from your department or organization. These people are part of your presentation team, even though some or all of them may not present information. Teams are common in many of the sales forces I coach, especially those in financial services and real estate. The “seller-buyer” relationship is very clear when representatives of two companies meet.

That same relationship exists within organizations when several co-workers from one department present information to a team of workers from another department. One group is usually selling an idea, and the other group is asked to buy in. The seller-buyer relationship typically involves a persuasive argument.

I don't want to condense every possible presentation situation into a seller-buyer theme, but when a clear separation of duties exists within the group, some type of persuasive argument usually is being presented. Otherwise, what is the point of gathering members from diverse departments if not for consensus?

Regardless of why members of your team are involved, you can strategize a seating plan before everyone has taken their chairs in the room. Let's separate the teams by using the simple terms their team and your team. Figure 27.4 shows how you might seat some of the attendees at the meeting.

Figure 27.4. Try to have some of your team in the observer seats and some of their team in the power/input seats.

Obviously you want the power seats to be taken by members of their team, especially for a persuasive presentation. If you can identify key players from their team, try to get a few of them into the power seats. Following that, any of their team's subordinate decision makers or support staff should occupy some of the input seats. Naturally, you want your team to blend in, so use the remaining input seats for members of your team, specifically those who are not presenting at the meeting.

Finally, save some of the observer seats for your team, especially for those who will be presenting during the meeting. Then, when they are ready to speak, they've had the opportunity to glance at others during your presentation to notice key reactions, interest level, and so forth. Awareness of any details about the group's reactions to information is invaluable to each presenter. In addition, members of your team occupying the observer seats are probably familiar with your presentation. They don't need to be as attentive to your words at every moment.

Following the presentation, you should regroup with your team and discuss the behavior observed during the meeting. Someone might have noticed a perplexed look when a certain subject was covered. Another member of your team might have observed someone taking notes as soon as a specific chart was presented. The observers can also notice people nodding off; maybe the presentation is longer than it should be. In any event, the feedback from those in the observer seats can be helpful in preparing for your next presentation.

Sit-Down Scenarios

Let's scale down the setting to the times when you are just sitting down. In these meetings, typically in a conference room, you might spend a few minutes standing and giving a presentation and then sit to continue the discussion. The seating positions can still be used effectively.

Keep in mind that when seated, the position of your shoulders still controls the rest and power positions discussed in Chapter 22, “The Message—Scripting the Concept” (refer to Figure 22.3 for a visual example). When your shoulders match the shoulders of another person, you are in a power position in relation to that person (as he is with you). When your shoulders are at an angle to another person, you are in a rest position. Your goal is to be in a seat where the angles of your body can be used effectively with the greatest number of people in the room.

For example, avoid putting yourself in a center-seating situation at a conference room table. Take a look at Figure 27.5. Let's say that the man in the center of the group, at the head of the table, is leading the meeting. You might think he is in a power position in relation to the others on his right and left. However, he can take a power position only with the person directly opposite, at the other end of the table.

The seat at the head of the table is not as effective, unless you are facilitating a meeting rather than leading it. When facilitating, you represent a neutral position. This is similar to an arbitrator or mediator. If you are playing such a role, then consider a center-seating position in relation to the group.

If you want to lead and control a meeting, you have a better chance from one of the corner seats. Look at Figure 27.6. It's the same group of people, shown from a different position. The woman wearing the eyeglasses has a power seat in relation to the others at the table. She is able to square her shoulders or angle them to many different people by swiveling her chair or shifting the upper part of her body.

Figure 27.5. The person at the head of the table is limited by his center position. He can create a power position with only one other person at the table, the one opposite him.

Figure 27.6. The woman wearing the eyeglasses occupies a power seat. The corner seats are the most effective in these conference room settings.

This strategy enables you to gain a wider perspective of the entire group. In addition, documents or other items will be easier to angle for view when you take one of the corner seats.

Handling One-to-One Situations

What happens when you are faced with one or two people in the room with you? You can still have a seating strategy to help your message along. For one-to-one meetings, use your rest and power positions in the same way as you do in a conference room setting. The smaller the group, the easier it becomes to use body angles to your advantage.

Create Angles

The most common situation to avoid is one in which you are directly opposite the other person and your shoulders match each other. The goal is to avoid having your shoulders parallel to the other person in a “squared-off” position. Angling your body or your chair is the easiest way to avoid squaring off to the other person. Look at Figure 27.7. In the background of the photo you see two people standing and having a conversation. Because their shoulders match, they are both in a power position relative to each other. When two people square off like that, it's as if their bodies are yelling at one another. In the foreground of the same image, the two women are seated, but they are at angles to one another.

Figure 27.7. Communication is more effective when people are at angles to one another.

You can put yourself into an angled position in relation to another person in a number of ways. When seated, you can choose a corner of a table; if you are standing and someone else is sitting, you can lean on the edge of a desk (half-standing) and keep your shoulders angled to the seated person.

Share Perspective

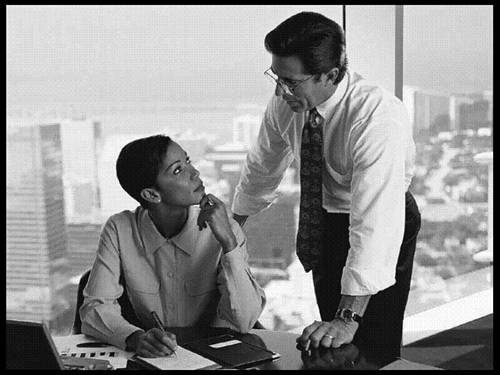

When two people look at something from completely different angles, they are not sharing a common perspective. This is not really a problem when the object is large enough to be seen from a distance, such as an image projected on a screen. If the object is meant for an audience of one, then perspective becomes an issue.

The most common object for one person to look at is a document. If you are opposite a person when you hand over a document, you immediately lose a common perspective. The person is looking down at the piece of paper, and you are looking at the same object upside-down. The perspective is different for each of you. It will be more difficult for you to point out specifics in the document from your perspective. You'll probably end up stretching your neck and rotating your head at some weird angle. Try to get the same perspective on the object as the other person.

Figure 27.8 shows a man standing next to a woman seated at a table. They share a common perspective of the document, which makes communication more effective. When people have the same point of view (literally) on something, the message is easier to convey and interpret.

Figure 27.8. By standing to the side, the man has the same perspective of the document as the woman.

Once equal perspective is achieved regarding the document, the man can return to his original position at the other side of the table and continue the discussion, meeting, or presentation.

The same perspective can also be achieved when two people are sitting. In Figure 27.9, the two men have the same perspective in looking at the papers in front of them. It will be easy for one of them to point to information on the sheets if necessary to facilitate the discussion. Imagine how difficult it would be if one of them were standing opposite and looking over the top of the papers to point out something specific.

Figure 27.9. Two people sitting side by side share the same perspective when looking at documents.

Tip from

Don't make your effort to get a common perspective so obvious that the other person wonders what you are doing. For example, if you are in a conference room with one other person and the table is long enough to hold 20 people, don't sit right next to the person. Instead, take a corner seat, if you can. Then, when you need to share a document, you can always get up and stand to the side of the person to point out information in the document.

Scan the Eyes

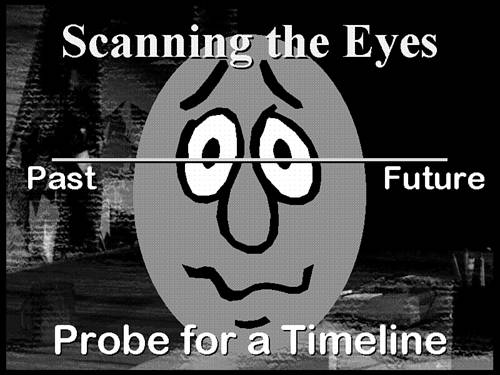

A lot of information stored in your brain is in the form of pictures. These visual references are tucked away neatly in your brain waiting for retrieval. For example, if you think about your high school biology teacher, a visual image pops into your head, and you see that person in your mind's eye, so to speak. You even visualize situations that haven't happened. If I ask you to think about your own road to success, you create a little picture in your brain as you see yourself in some type of successful moment. Everyone uses visual references. When one of those references is retrieved, the eyes move in some direction to see the image in the brain.

Therefore, in many one-to-one situations, the eyes of the other person can offer you some interesting clues as to what he might be thinking. As an observer, you can scan the eye movement of a person whenever you say something thought provoking. To interpret the other person's reaction, however, you need to learn how he looks for the images he creates.

The easiest approach is to probe for a timeline. Figure 27.10 shows how you place an imaginary timeline in front of the person's face. The timeline is always from your point of view. Start with the assumption that the person's past is to your left, and his future is to your right.

Figure 27.10. When scanning the eyes of another person, place an imaginary timeline in front of him.

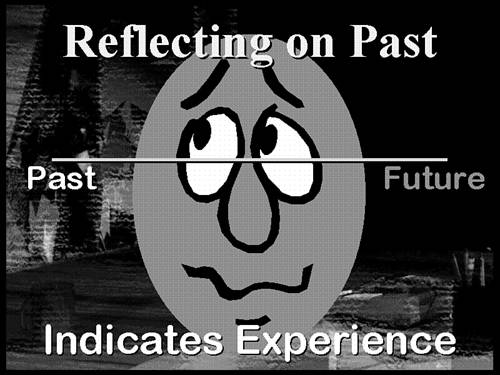

When you ask a question involving reflection or something in the past, the person normally shifts his eyes in one direction to look up the visual image of the experience. You can observe which direction the eyes travel as the person recalls the experience. Not everyone glances in the same direction to look up an image, but for most people, that direction is up and to the right. Whatever the direction, it represents the past. Figure 27.11 shows how a person's eyes might move when he reflects on a past experience. In this example, the direction of his eyes matches your timeline.

Figure 27.11. When a person reflects on the past, his eyes move in some direction.

If his eyes shift the opposite way of your imaginary timeline, then reverse your timeline and realize that he looks up his past differently (to your right). You first have to notice how the person recalls past experiences to establish the end points of your timeline. Whatever the direction of his eyes, it represents the past on your timeline.

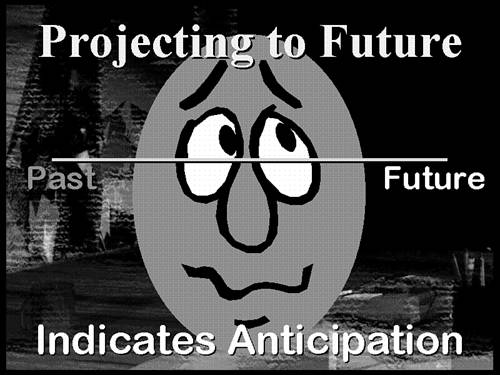

After you know the person's past, whenever you prompt a thought-provoking glance in the opposite direction, the person is likely indicating anticipation of something in the future. Figure 27.12 shows an established timeline with a glance to the person's left, indicating a vision of the future.

Figure 27.12. After a timeline is established and you know the person's past, a shift of his eyes in the opposite direction indicates anticipation.

I have always taken the position that, whenever a person paints a picture of his future, it is always positive, unless he has some specific reason to expect something negative to happen. Using the assumption that a person's view of the future is ultimately optimistic, a shift of a person's eyes to the “future” on the timeline you establish may be the most opportune moment for you to close the deal, so to speak. After all, if the person appears to be looking forward to using your product or service, take that eye movement as a hint and go for it. Close the deal, ask for the order, complete the call to action.

The eyes give other hints, as well. For example, if the person is staring directly at you and not shifting his eyes at all, there's a good chance that he is not listening. He is probably giving you the courtesy of direct eye contact, but he is probably drifting away in his thoughts. Break the eye contact and he will be attentive again.