CHAPTER 1

The Emergence of the Eurodollar Market

Galen Burghardt, Terry Belton, Morton Lane, Geoffrey Luce, and Rick McVey

The Eurodollar market—the market for dollar-denominated deposits outside of the United States—is perhaps the largest and most liquid of the world’s short-term dollar markets. At the same time, swaps based on the London Interbank Offered Rate (LIBOR) and Eurodollar futures, together with their option counterparts, are without question the most liquid and actively traded money market derivatives. For that matter, the LIBOR-based swap market has become so large and liquid that swap rates have largely displaced government bonds as the standard of value against which fixed income instruments are compared.

Our purpose in this chapter is to provide a thumbnail history of where these markets came from and how they got to be as big as they are.

THE REVOLUTION IN FINANCE

The 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s witnessed a complete transformation in the world of banking and finance. Before 1970, banks did business by accepting short-term deposits at low regulated rates and then offering longer-term business and personal loans at higher rates.

Then came the 1970s and inflation, which forced the banking system to realize two things. First, the high interest rates produced by inflation forced cash out of the regulated deposit market and led to the creation of an active, unregulated money market. If banks were to compete for cash, the shackles of deposit regulation would have to be removed, and in time they were. Second, the steep inversion of the yield curve, which was most extreme during Paul Volcker’s first two years as Chairman of the Federal Reserve in 1979 and 1980, forced the banks to face up to the yield curve risk that went with the old model of banking. By the 1980s, cash had become a traded commodity, and banks knew that they had to find ways to manage their interest rate risk.

At the same time, the finance profession was hard at work fanning the flames of revolution. The intellectual offsprings of Markowitz, Modigliani, and Miller produced a great outpouring of new ideas that led to the trading of options on exchanges, the stripping of Treasury bonds into their individual parts, the worldwide integration of money markets, and the market for interest rate derivatives.

Two innovations in applied finance matter most for the readers of this book. First was the idea that each cash flow associated with a coupon-bearing bond not only could, but should, be treated as a zero-coupon bond. This insight allowed financial engineers to look at any given bond as simply a collection of zeros, each of which could be valued separately and consistently. Second was the idea that one could trade the price of a commodity without trading the commodity itself. This insight allowed the market to focus in on price or interest rate risk and to develop interest rate derivatives—swaps, forward rate agreements, and futures on bank deposit rates and government bonds. It was interest rate derivatives that finally allowed bankers to understand their interest rate risk and to manage it cheaply and effectively.

Zero-coupon bonds and interest rate derivatives really took hold in the 1980s, as people learned how to strip the coupons from U.S. Treasury bonds and to reassemble them, and how to unbundle and repackage residential mortgages in the form of mortgage-backed securities.

By the time the 1990s arrived, most of the real thinking and innovation was in place for the revolution in banking and finance to take complete hold. The 1990s were a time of growth, expansion, and consolidation for the interest rate derivatives market. Interest rate swaps in the over-the-counter market and Eurodollar futures in the exchange-traded market grew by leaps and bounds. Moreover, swaps and bank deposit rate futures spread to every major money market in the world. At this writing, swap rates have muscled their way into the center of the fixed income world and have become the interest rates against which nearly all yields are compared. It is now standard practice for every well-run bank to state its interest rate exposure in terms of 3-month Eurodollar futures equivalents.

THE FUTURES REVOLUTION

Such a complete transformation of the world of banking and finance would not have been possible without futures in general and Eurodollar futures in particular.

The futures market pioneered the idea that one could trade the price separately from the commodity itself. Economists have argued for years that a commodity possesses several useful characteristics, only one of which is its price. And once one could trade the price without actually buying or selling the commodity, the costs of hedging and speculating dropped like a stone. The futures market also pioneered a set of risk management practices that have slowly taken hold in other parts of the financial world. The ideas of requiring collateral to guaranty performance, marking positions to market every day, and settling up gains and losses in cash on a regular basis have had a wonderfully tonic effect on risk managers outside of the futures world.

The idea of financial futures took hold in the early 1970s. Although futures had been traded on a wide range of metals and agricultural commodities since the middle of the 19th century in this country, and had a history reaching back several centuries in other parts of the world, the idea of trading futures contracts on things like foreign currencies and interest rates at first struck people as outrageous.

By the early 1980s, however, we were able to trade futures contracts on foreign currencies, stock indexes, government bonds, and Eurodollar bank deposit rates. Of these, perhaps the most important was the Eurodollar contract, without which the interest rate swap market would never have gotten off the ground and grown the way it has. Eurodollar futures are the financial building blocks of the swap market. They provide the rates from which swaps can be priced, and they provide the tools that dealers need to hedge them.

KEY MONEY MARKET DEVELOPMENTS

The Eurodollar market now dominates trading in private short-term money market instruments. This was not always so. For almost two decades, until the early 1980s, certificates of deposit (CDs) issued by U.S. banks played this role.

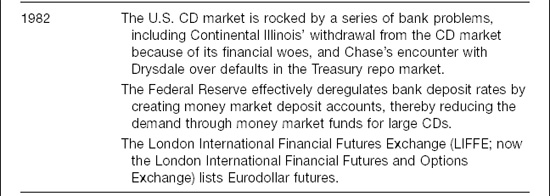

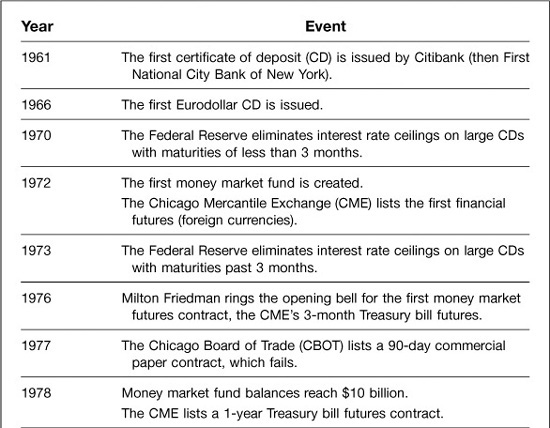

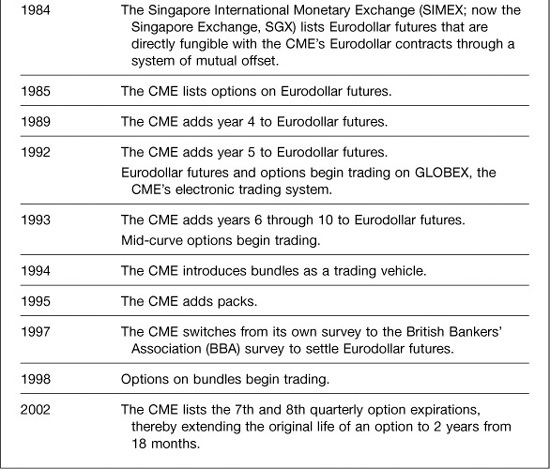

The seeds of the money market revolution were planted in 1961 when Citibank (then First National City Bank of New York) issued the first CD. This was followed in 1966 with the issuance of the first Eurodollar CD. (See Exhibit 1.1 for a summary of key money market developments.)

EXHIBIT 1.1

Milestones in the Development of the Dollar Money Markets

The importance of the CD was that it could be traded. Until CDs came along, bank deposits were a sticky kind of liability or asset (depending on whether you were the bank or the depositor). CDs, however, could be bought and sold just like Treasury bills. As a result, banks and depositors could change the shapes of their respective balance sheets at will. The value that depositors placed on the right to trade CDs was reflected in a lower yield than was paid on conventional term deposits.

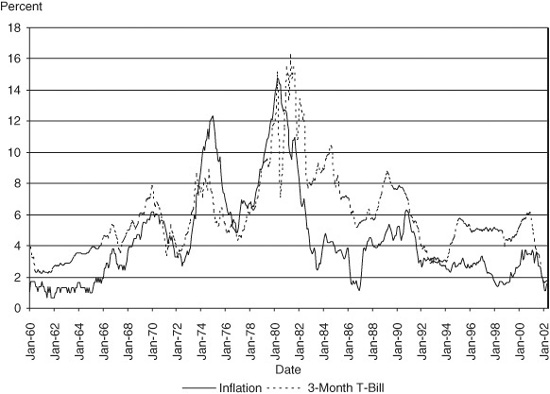

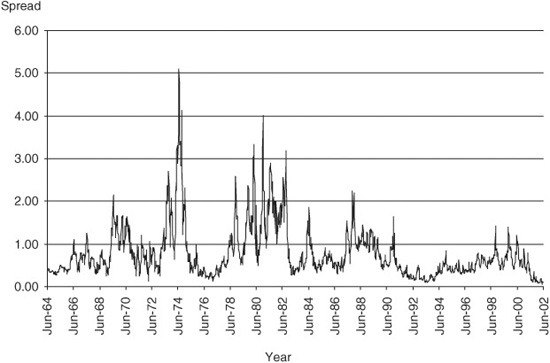

CD issuance exploded in the 1970s because of the combined forces of inflation and the ceilings placed on bank deposit rates by the Federal Reserve’s Regulation Q. Exhibit 1.2 shows the effect of rising inflation on short-term interest rates. The upper limits on the rates banks could pay put banks at a competitive disadvantage in the market for funds.

EXHIBIT 1.2

Inflation and 3-Month Treasury Bill Yields

1960 through May 2002

Large CDs were finally freed from deposit rate regulation, and gave banks a way out. Money market funds became a conduit for placing large CDs in the hands of people who otherwise would have held their liquid assets at banks. Rising inflation throughout the 1970s kept forcing interest rates up, and CDs became a major force in U.S. money markets.

The beginning of the end of the CD market’s explosive growth came in 1982. For one thing, the Federal Reserve took a big step in removing regulations from bank deposits by creating money market deposit accounts in December 1982. These new accounts meant that people could get competitive interest rates directly from banks rather than indirectly through money market funds.

For another, the banks that issued CDs were running into serious financial problems that greatly affected the world’s perception of banks’ creditworthiness. Continental Illinois, for example, faced huge loan losses on its Mexican debt portfolio and had to withdraw from the domestic CD market in the summer of 1982. Chase Manhattan encountered defaults in the Treasury repo market through its dealings with Drysdale. Until these problems surfaced, the CDs of the top ten U.S. banks had been bought and sold as if they were part of a nearly homogeneous, high-quality pool. Continental’s and Chase’s problems made it clear that not all CDs were the same, and the secondary market for CDs lost much of its liquidity as a result.

The combined effect of the new money market deposit accounts and the credit problems of various large banks was a huge reduction in the demand for CDs.

WHY EURODOLLARS?

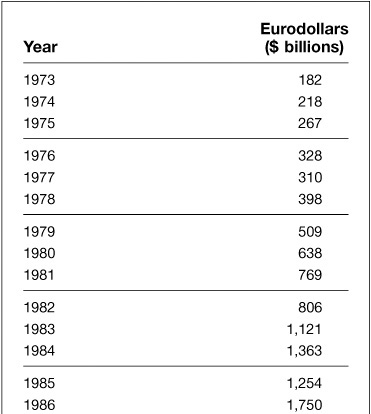

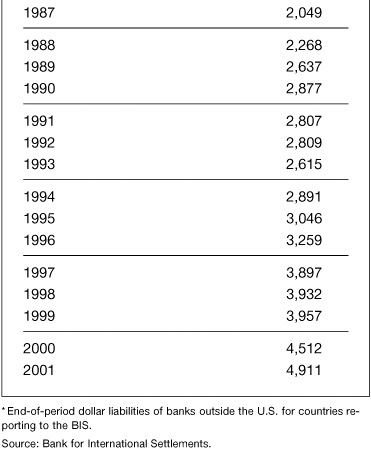

At the same time, the Eurodollar market was moving from strength to strength. As shown in Exhibit 1.3, the Eurodollar market continued to grow even after 1982 when the CD market began to shrink.

EXHIBIT 1.3

Growth of the Eurodollar Market: Eurodollars Outstanding*

Year-End 1973 through 2001

The Eurodollar market owes its early success to a variety of forces:

• Eurodollar deposits were always unregulated and therefore were a competitive source of funds during the years before the interest rate ceilings on domestic deposits were lifted by the Federal Reserve.

• Eurodollar deposits were a cheaper source of funds to the extent they were free of reserve requirements and deposit insurance assessments.

• The dollar was becoming the currency of choice for a great number of the world’s trade and asset transactions.

• The Soviet Union’s international trade dealings required them to hold substantial dollar deposits, but they were unwilling to hold them in banks in the United States.

Reasons for the continued success of the Eurodollar market throughout the 1980s are less clear, but three things stand out.

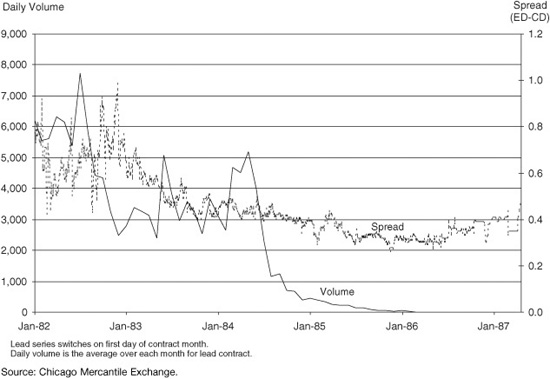

First, the Eurodollar market escaped the worst of the problems of creditworthiness that had such a depressing effect on the U.S. CD market. Second, money markets were almost completely integrated by the middle of the 1980s, so that banks were nearly indifferent between borrowing domestically or borrowing abroad. This point is illustrated clearly in Exhibit 1.4, which shows that the difference between Eurodollar deposit rates and CD rates was nearly constant by the beginning of 1986. The difference between the two rates represented nothing more than the cost of reserve requirements and deposit insurance. Third, interest rate derivatives such as swaps and caps appeared in the early 1980s and proved to be very successful financial instruments.

EXHIBIT 1.4

CD Futures Volume versus Eurodollar/CD Futures Rate Spread

EURODOLLAR FUTURES

The Eurodollar futures contract, which today is the most widely traded money market contract in the world, was the product of considerable experimentation. The key events leading up to the listing of the Eurodollar contract are summarized in Exhibit 1.1. To begin, the CME listed futures contracts on foreign currencies in 1972. These were the first financial futures ever traded. Then, in 1976, the CME listed futures on 3-month Treasury bills. These were the first money market futures ever traded.

The Treasury bill contract proved successful, and the Chicago exchanges as well as the newly formed New York Futures Exchange (NYFE) began to look elsewhere for new products. As shown in Exhibit 1.5, the events surrounding the financial upheavals of 1973 and 1974 proved just how volatile the spread between private money market instruments and Treasury bills could be. In the face of this much volatility in the private money market credit spread, Treasury bill futures could be a very bad hedge for private short-term liabilities.

EXHIBIT 1.5

The Spread between 3-Month CD and Treasury Bill Rates

June 1964 through June 2002

From this, the futures exchanges concluded that the world could use a futures contract on private short-term obligations. The first effort was the Chicago Board of Trade’s (CBOT) contract on 90-day commercial paper, which was listed in 1977. This contract failed, largely because 90-day commercial paper was not a sufficiently homogeneous commodity. The credit risks behind the individual issuers, especially in light of the problems created by Chrysler’s brush with bankruptcy, loomed much too large in people’s minds for them to take the contract seriously. The CBOT’s second effort, a 30-day commercial paper contract, also failed.

The exchanges turned next to the domestic CD and Eurodollar markets, which had been growing rapidly since 1972. The CME’s records show that its Interest Rate Committee was working on the details of both a domestic CD and a Eurodollar contract as early as July 1979, which predates the onset of Volcker’s monetary experiment.

By the spring of 1980, the CBOT, the CME, and the NYFE had all filed their respective applications. They did not get approval until the next year, and in July 1981, all three CD contracts were listed for trading.

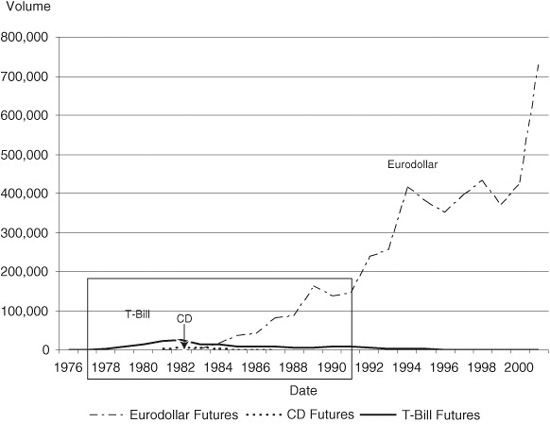

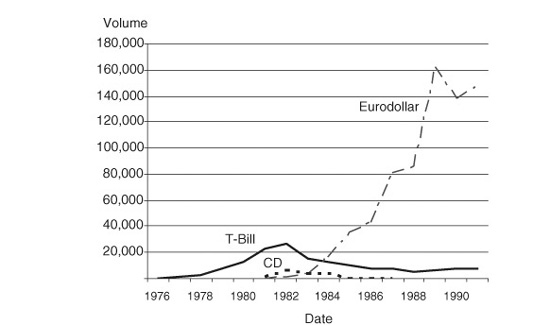

Technically, the NYFE’s contract was listed first. Of the three, however, the CME’s prevailed and began its short but comparatively active trading life, which is charted in Exhibit 1.6. The race does not always go to the swift!

EXHIBIT 1.6

Average Daily Trading Volume for 3-Month Treasury Bill, Certificate of Deposit, and Eurodollar Futures 1976 through 2001

All three exchanges also had been working on various forms of a Eurodollar futures contract, which posed interesting design challenges. The biggest of these challenges was answering the question of delivery. Eurodollar CDs were a tradable commodity, but they represented a comparatively small slice of the Eurodollar market. Even so, the CBOT filed for approval but never listed a contract based on the delivery of Euro CDs.

Eurodollar time deposits, on the other hand, made up a large part of the Eurodollar market but were not negotiable. The CME originally proposed a time deposit contract that would be settled by the short opening a time deposit on behalf of the long. This approach had the advantage of preserving delivery integrity, but it was cumbersome, and the idea of cash settlement was floated.

At the time, there was no such thing as a cash-settled futures contract. Once the CME was satisfied that the cash settlement procedures would not be subject to manipulation, they filed a Eurodollar contract on that basis, as did the NYFE. Because the idea of cash settlement was breaking new ground, the Commodity Futures Trading Commission’s deliberations on the concept required considerable time. Their approval when it came, however, was revolutionary and paved the way for stock index futures as well.

Although Eurodollar futures took longer to gain regulatory approval, the end result was a contract that was rooted in a large, liquid, and growing market that was designed to be insulated from the dangers posed by heterogeneous bank credits.

The device that protected the Eurodollar contract from the forces that brought the CD contract down was cash settlement. Initially, the final settlement price on the last day of trading for a Eurodollar contract was determined by the CME, which conducted a poll of banks in London. The CME’s survey had two important features:

• The CME asked each bank its perception of the rate at which banks in London were willing to lend to other prime quality banks. The CME avoided in this question asking a bank the rate at which it was lending to any other particular bank.

• The CME threw out high and low responses and calculated the final settlement price using the middle quotes.

The effect of the first of these features was that the survey skirted the problem of individual bank credits. The intended effect of the second was to insulate the final settlement price from capricious manipulation. A bank that misrepresented the market outrageously would have no effect on the final outcome. As a result, the banks polled in the CME’s survey likely responded truthfully, although it would be naïve to suppose that their responses never reflected their positions in the cash and futures markets.1

THE DEATH OF CD FUTURES AND THE BIRTH OF EURODOLLAR FUTURES

The big turning point in the lives of these two contracts came in 1982, which was also a watershed for their respective cash markets. The depressing effect on the CD market of deposit deregulation and the financial difficulties of banks such as Continental Illinois and Chase Manhattan were felt as well in the CD futures market. The banks’ credit problems also unsettled the market for the CD futures contract by clouding the picture about what would be deliverable.

For some time, the CDs of the top ten banks had been traded almost as if they were a homogeneous commodity. When Continental withdrew from the domestic CD market in 1982 and other banks began to feel the effects of financial stress, the upper tier of the CD market began to lose its homogeneity. Traders became more acutely aware of whose CDs were offered by other traders and how much of any one bank’s CDs were on their books.

This concern about credit quality spilled over into the CD futures markets, where traders began to worry about just which bank’s CDs they would receive if they took delivery. The price of a futures contract that involves the delivery of an actual commodity is driven by the price of the commodity in the eligible set that is cheapest to deliver. Traders became cautious about trading CD futures because there was so much uncertainty both about what and how cheap the cheapest to deliver might be.

At about the same time, as shown in Exhibit 1.4, the integration of world money markets was stabilizing the spread between U.S. and Eurodollar CD rates. From the standpoint of futures traders, this stabilization of the spread meant that Eurodollar and CD futures were becoming nearly perfect financial substitutes for one another. The only differences came down to issues such as liquidity and deliverable supply. Given the headaches caused by the uncertain quality of deliverable supply for the CD contract, traders began to favor Eurodollar futures.

The results of these various developments are summarized in Exhibit 1.6. CD futures trading had peaked by early 1983. By 1984, Eurodollar futures trading had caught up with and passed trading in CD futures. By 1985, Eurodollar futures were more actively traded than 3-month Treasury bill futures and have been so ever since. By 1986, CD futures were dead, although the CME did not officially bury the contract until 1987.

THE MARKET FOR INTEREST RATE DERIVATIVES AT THE BEGINNING OF THE 21ST CENTURY

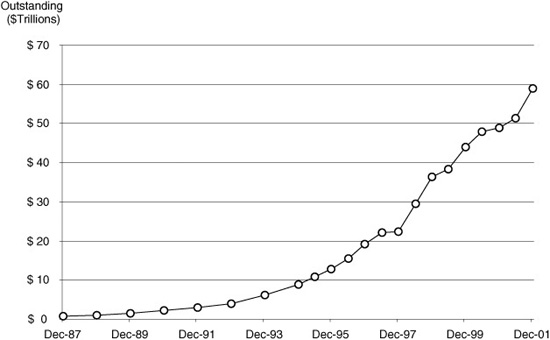

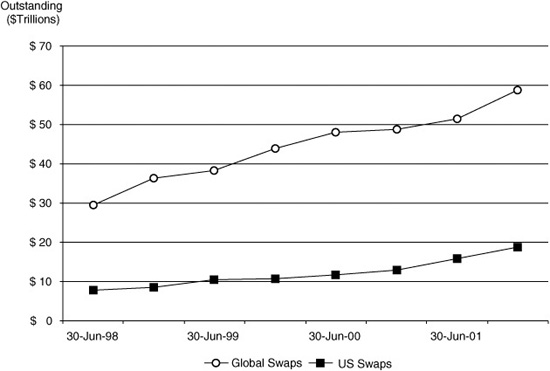

At this writing, in 2002, the interest rate derivatives market is highly developed and quite complete. There are exchange-traded money market futures for the wholesale market and over-the-counter swaps for the retail corporate market. There are options on futures, interest rate caps, and options on swaps (swaptions). And one can find these instruments in every major financial market in the world. The growth of the markets has been explosive. Exhibit 1.7, for example, shows the global growth of swaps outstanding from 1987 through 2001. Exhibit 1.8 displays the growth of U.S. versus global swaps from 1998 through 2001.

EXHIBIT 1.7

Global Interest Rate Swaps Outstanding Converted to U.S. Dollars

EXHIBIT 1.8

Global versus U.S. Interest Rate Swaps Outstanding Converted to U.S. Dollars

Exchange-Traded Money Market Futures and OTC Interest Rate Swaps

The exchange-traded and over-the-counter (OTC) interest rate markets go hand in hand but appeal to very different markets. Eurodollar futures are for the wholesale financial market—the dealers who price and hedge interest rate swaps and the banks whose business it is to serve as conduits for cash and to manage their exposure to the yield curve with considerable finesse. Eurodollar futures are great at what they do but require their users to settle gains and losses daily in cash; to be able to deal with yield curve approximations; to understand the subtleties of forward, zero-coupon, and coupon yield curves; and to appreciate the importance of convexity in understanding rate relationships between competing interest rate products.

The OTC swap market is best designed for retail corporate users because they transact less frequently and work under a different set of accounting, regulation, and tax standards. For corporate treasurers, the cash flows are less frequent and more predictable. And the collateral requirements often are less onerous. Using swaps correctly does require a solid appreciation of credit risk, counterparty risk, and balance sheet issues that tend not to be a problem in the futures market.

Options on Futures, Forward Rates, and Swaps

In the market for options on futures, exchanges provide a rich and varied set of possible instruments. These include the standard quarterly options for which the option and the underlying futures contract expire on the same day, and the serial and mid-curve options for which the options expire before the underlying futures contract. The over-the-counter market offers two basic choices: caps, which represent a sequence of options on forward rates, and swaptions, which represent single options on a term swap rate, which in turn represents a combined sequence of forward rates.

Markets around the World

If we take the presence of an exchange-traded money market futures contract as evidence of an active interest rate derivatives market, we can conclude that all of the world’s major money markets are covered. Exhibit 1.9 provides a list of exchanges on which one can trade money market futures and options. The list shows how widely accepted interest rate derivatives trading has become.

EXHIBIT 1.9

Exchanges That Trade Money Market Futures