chapter 18

Essentials of Networking

“Information at your fingertips.”

—BILL GATES

In this chapter, you will learn how to

■ Describe the basic roles of various networked computers

■ Discuss network technologies and Ethernet

■ Describe a typical Ethernet implementation

It’s hard to find a computer that’s not connected to a network. Whether you’re talking about a workstation that’s part of a large enterprise network or discussing that smartphone in your pocket, every computer has some form of network connection. CompTIA includes a lot of networking coverage in the CompTIA A+ exams.

This chapter dives into networks in detail, especially the underlying hardware and technologies that make up the bulk of networks in today’s homes and businesses. The discussion starts by examining the roles computers play in networking, helping you associate specific names with devices and services you’ve undoubtedly used many times already. The second portion, and the heart of the chapter, focuses on the now-standard network technology used in most networks, regardless of operating system. The final section examines how this network technology looks in a normal workplace.

1101

■ Roles Hosts Play in Networks

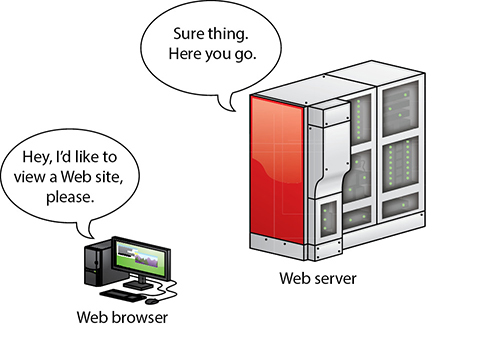

Take a moment to think about what you do on a network. Most of us, when asked, would say, “surf the Internet,” or “watch YouTube videos,” or maybe “print to the printer downstairs.” These are all good reasons to use a network, but what ties them together? In each of these situations, you use your computer (the local host) to access “stuff” stored on a remote host (not your local computer). A host is any computing device connected to a network. So what do remote computers have that you might want (see Figure 18.1)?

• Figure 18.1 Accessing remote computers

Each networked host fulfills a certain role. A remote computer called a Web server stores the files that make up a Web site. The Web server uses server programs to store and share the data. So the role of the Web server is to provide access to Web sites. Two popular Web server programs are Apache HTTP Server and Microsoft Internet Information Services (IIS). When you access a Web site, your Web browser (likely Mozilla Firefox, Google Chrome, Safari, or Microsoft Edge) asks the Web server to share the Web page files and then displays them (see Figure 18.2). Because your computer asks for the Web page, we call it the client. That’s the role of the local host in this example. The remote computer that serves the Web site is a server.

• Figure 18.2 Accessing a Web page

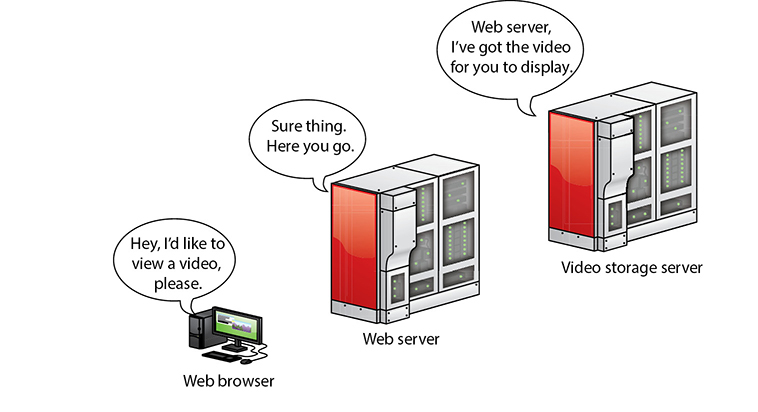

But what about YouTube? YouTube also uses Web servers, but these Web servers connect to massive video databases. Like a normal Web server, these remote computers share the videos with your client device, but they use special software capable of sending video fast enough that you can watch it without waiting (see Figure 18.3).

• Figure 18.3 Accessing a YouTube page

But we don’t need the Internet to share stuff. Figure 18.4 shows a small home network with each computer running Windows. One of the computers on the network has a printer connected via a USB port. This computer has enabled a printer-sharing program built into Windows so that the other computers on the network can use the printer. That computer, therefore, takes on the role of a print server.

• Figure 18.4 Sharing a printer in Windows

No matter how big the network, we use networks to share and access stuff. This stuff might be Web pages, videos, printers, folders, e-mail messages, music . . . what you can share and access is limited only by your ability to find a server program capable of sharing it and a client program that can access it.

Each type of server gets a label that defines its role. A networked host that enables you to access a bunch of files and folders is called a file server, or fileshare. The networked host you use to access e-mail messages? It’s called a mail server. Truth in advertising!

Network people call anything that one computer might share with another a resource. The goal of networking, therefore, is to connect computers so that they can share resources or access other shared resources.

To share and access resources, a network must have the following:

1. Something that defines and standardizes the design and operation of cabling, network cards, and the interconnection of multiple computers

2. An addressing method that enables clients to find servers and enables servers to send data to clients, no matter the size of the network

3. Some method of sharing resources and accessing those shared resources

Let’s look now at the first of these network needs and discuss current industry standards.

■ Networking Technologies

When the first network designers sat down at a café to figure out how to get two or more computers to share data and peripherals, they had to write a lot of notes on little white napkins to answer even the most basic questions. The first question was: How? It’s easy to say, “Well, just run a wire between them!” But that doesn’t tell us how the wire works or how the computers connect to the wire. Here are some more big-picture questions:

■ How will each computer be identified?

■ If two or more computers want to talk at the same time, how do you ensure that all conversations are understood?

■ What kind of wire? What gauge? How many wires in the cable? Which wires do what? How long can the cable be? What type of connectors?

Clearly, making a modern network entails a lot more than just stringing up some cable! As you saw a bit earlier, most networks have one or more client machines, devices that request information or services, and a server, the machine that hosts and shares the data. Both clients and servers need network interface controllers (NICs) that define or label the machine on the network. A NIC also breaks files into smaller data units to send across the network and reassembles the units it receives into whole files. You also need some medium for delivering the data units between two or more devices—most often this is a wire that can carry electrical pulses; sometimes it’s radio waves or other wireless methods. Finally, a computer’s operating system has to be able to communicate with its own networking hardware and with other machines on the network. Figure 18.5 shows a typical network layout.

• Figure 18.5 A typical network

Frames and NICs

Data is moved from one device to another in discrete chunks called frames. NICs create and process frames.

Every NIC in the world has a built-in identifier, an address unique to that network card, called a media access control (MAC) address. A MAC address is a binary number, meaning it’s a string of ones and zeros. Each one or zero is called a bit.

Cross Check

Cross Check

Binary

You learned about binary way back in Chapter 3, so cross check your memory and answer these questions. What components use binary? What’s the difference between a one and a zero in binary?

The MAC address is 48 bits long, providing more than 281 trillion MAC addresses, so there are plenty of MAC addresses to go around. Because people have trouble keeping track of that many ones and zeros, we need another way to display the addresses. Hexadecimal is shorthand for representing strings of ones and zeros. One hex character is used to represent four binary characters. Here’s the key:

0000 = 0

0001 = 1

0010 = 2

0011 = 3

0100 = 4

0101 = 5

0110 = 6

0111 = 7

1000 = 8

1001 = 9

1010 = A

1011 = B

1100 = C

1101 = D

1110 = E

1111 = F

So, MAC addresses may be binary, but we represent them by using 12 hexadecimal characters. These MAC addresses are burned into every NIC, and some NIC makers print the MAC address on the card. Figure 18.6 shows the System Information utility description of a NIC, with the MAC address highlighted.

• Figure 18.6 MAC address

Hey! I thought we were talking about frames! Well, we are, but you need to understand MAC addresses to understand frames.

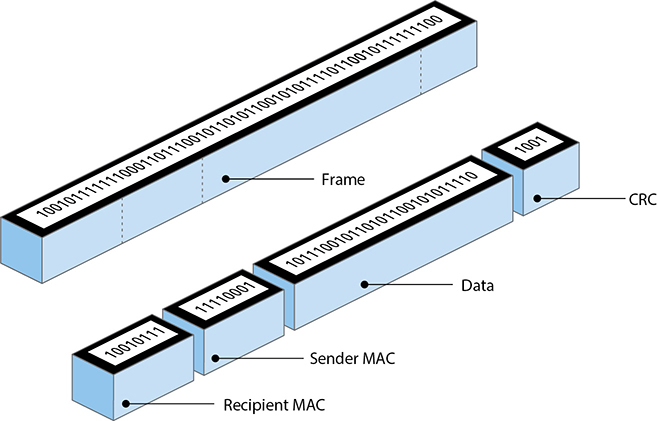

The many varieties of frames share common features (see Figure 18.7). First, frames contain the MAC address of the network card to which the data is being sent. Second, they have the MAC address of the network card that sent the data. Third is the data itself (at this point, we have no idea what the data is—certain software handles that question), which can vary in size depending on the type of frame. Finally, the frame must contain some type of data check to verify that the data was received in good order. Most frames use a clever mathematical algorithm called a cyclic redundancy check (CRC).

• Figure 18.7 Generic frame

Try This!

Try This!

MAC Address Search

Every personal computing device has a MAC address assigned to each network connection type it offers. Any number of troubleshooting scenarios will have you scrambling to find a device’s MAC address, so try this!

You have many ways to discover the MAC address(es) in Windows, macOS, and Linux. The simplest is through the command-line interface. Here’s a method in Windows. At the prompt, type ipconfig /all and press ENTER. You’ll find the MAC address listed as the “Physical Address” under the Ethernet adapter Local Area Connection category.

Which command do you think would work at the Terminal in macOS and Linux? How do you figure out which switch to use? (Refresh your memory of commands in Chapter 15.)

This discussion of frames raises a question: How big is a frame? Or more specifically, how much data do you put into each frame? How do you ensure that the receiving system understands the way the data was broken down by the sending machine and can thus put the pieces back together? The hard part of answering these questions is that they encompass so many items. When the first networks were created, everything from the frames to the connectors to the type of cable had to be invented from scratch.

To make a successful network, you need the sending and receiving devices to use the same network technology. Over the years, many hardware protocols came and went, but today only one hardware protocol dominates the modern computing landscape: Ethernet. Ethernet was developed for wired networking, but even wireless networks use Ethernet as the basis for their signals. If you want to understanding networking, you need to understand Ethernet.

Ethernet

A consortium of companies, including Digital Equipment Corporation, Intel, and Xerox, invented the first network in the mid-1970s. More than just create a network, they wrote a series of standards that defined everything necessary to get data from one computer to another. This series of standards was called Ethernet. Over the years, Ethernet has gone through hundreds of distinct improvements in areas such as speed, signaling, and cabling. We call these improvements Ethernet flavors.

Through all the improvements in Ethernet, the Ethernet frame hasn’t changed in over 25 years. This is very important: you can have any combination of hardware devices and cabling using different Ethernet flavors on a single Ethernet network and, in most cases, the hosts will be able to communicate just fine.

Most modern Ethernet networks employ one of two speeds, 1000BASE-T or 10GBASE-T, which were preceded by 10BASE-T and 100BASE-TX. As the numbers in the names suggest, 10BASE-T networks run at 10 Mbps, 100BASE-TX networks (called Fast Ethernet) run at 100 Mbps, 1000BASE-T networks (called Gigabit Ethernet) run at 1000 Mbps, or 1 Gbps, and 10GBASE-T runs at speeds of up to 10 Gbps. All four technologies—collectively referred to as just plain Ethernet—use a star bus topology (discussed in the next section) and connect via a type of cable called unshielded twisted pair (UTP).

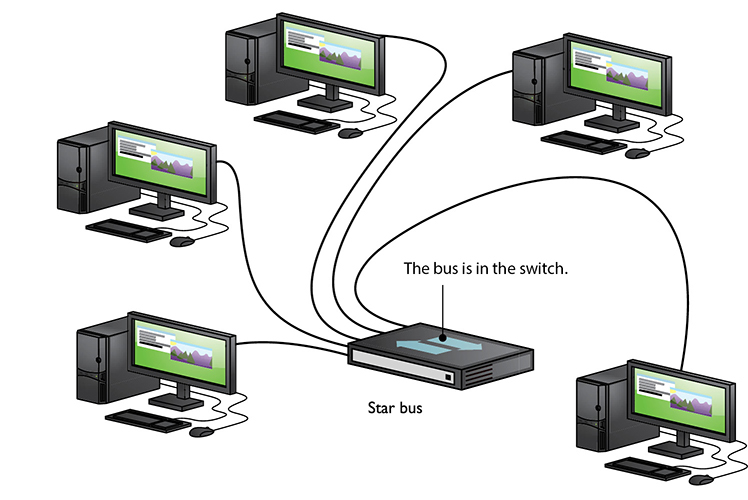

The Ethernet Star Bus

With all Ethernet networks, every individual host connects to a central box. You attach each system to this box via cables to special ports. The box takes care of all the tedious details required by the network to get frames sent to the correct systems. This layout, which looks something like a star, is called a star bus topology (see Figure 18.8). (The bus refers to the internal wiring in the box. The star refers to the wires leading from the box to the hosts.)

• Figure 18.8 Ethernet star bus

The central box—the switch—provides a common point of connection for network devices. Switches can have a wide variety of ports. Most consumer-level switches have 4 or 8 ports, but business-level switches can have 32 or more ports.

Early Ethernet networks used a hub. A switch is a far superior version of a hub and replaced hubs in the 2000s. (Why CompTIA continues to include hubs in the CompTIA A+ objectives is a mystery.) Figure 18.9 shows a typical consumer-level switch.

• Figure 18.9 A switch

Hubs and switches look pretty much identical and they perform the same basic job: taking the signal from one host and then repeating the signal out to other hosts. Even though they look the same and do functionally the same job, they do the job differently. Basically, hubs were stupid repeaters: anything sent in one port automatically went out all the other connected ports. Switches are smart repeaters: they memorize the MAC addresses of all the connected devices and only send out repeated signals to the correct host. This makes switched networks much faster than hubbed networks.

A simple example demonstrates the difference between hubs and switches. Let’s say you have a network of 24 machines, all using 100-Mbps NICs attached to a 100-Mbps hub or switch. We would say the network’s bandwidth is 100 Mbps. If you put the 24 systems on a 24-port 100-Mbps hub, you would have 24 computers sharing the 100 Mbps of bandwidth. A switch addresses this problem by making each port its own separate network. Each system gets to use the full bandwidth. The bottom line? Once switches became affordable, hubs went away.

The connection between a computer and a switch is called a segment. With most cable types, Ethernet segments are limited to 100 meters or less. You cannot use a splitter to split a single segment into two or more connections with an Ethernet network that uses this star bus topology. Doing so prevents the switch from recognizing which host is sending or receiving a signal, and no hosts connected to a split segment will be able to communicate. Splitters negatively affect signal quality.

Cheap and centralized, Ethernet’s star bus topology does not go down if a single cable breaks. True, the network would go down if the switch failed, but that is rare.

Unshielded Twisted Pair

Unshielded twisted pair (UTP) cabling is the specified cabling for 100/1000BASE-T as well as 10GBASE-T and is the predominant cabling system used today. Many types of twisted pair cabling are available, and which type should be used depends on the needs of the network. Twisted pair cabling consists of AWG 22–26 gauge copper wire twisted together into color-coded pairs. Each wire is individually insulated and encased as a group in a common jacket.

UTP cables come in categories that define the maximum speed at which data can be transferred (also called bandwidth). The major categories (Cats) are outlined in Table 18.1.

Table 18.1 Cat Levels

The Cat level should be clearly marked on the cable, as Figure 18.10 shows.

• Figure 18.10 Cable markings for Cat level

The Telecommunication Industry Association (TIA) establishes the UTP categories, which fall under the ANSI/TIA 568 specification. The American National Standards Institute (ANSI) accredits TIA (and many other) standards so that they assure things work across industry and, equally importantly, along with international standards. Currently, most installers use Cat 5e, Cat 6, or Cat 6a cable.

Shielded Twisted Pair

Shielded twisted pair (STP), as its name implies, consists of twisted pairs of wires surrounded by shielding to protect them from electromagnetic interference (EMI). STP is pretty rare for 1000BASE-T networks, primarily because there’s so little need for STP’s shielding; it only really matters in locations with excessive electronic noise, such as a shop floor area with lots of lights, electric motors, or other machinery that could cause problems for other cables. Some STP cables are rated for direct burial. A cable rated for direct burial will have a thicker jacket and some variety of waterproofing to make it suitable for outdoor open-air use or . . . direct burial underground.

Ethernet with Twisted Pair

The 10BASE-T and 100BASE-TX standards required two pairs of wires: a pair for sending and a pair for receiving. 10BASE-T ran on an ancient Cat version called Cat 3, but typically used at least Cat 5 cable. 100BASE-TX required at least Cat 5 to run. 1000BASE-T needs all four pairs of wires in Cat 5e and higher cables, and 10GBASE-T requires all four pairs, but in Cat 6 or higher. These cables use a connector called an RJ45 connector. The RJ (registered jack) designation was invented by Ma Bell (the phone company, for you youngsters) years ago and is still used today.

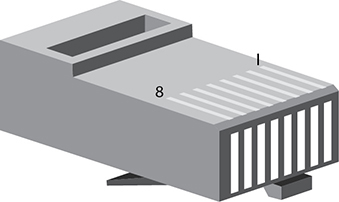

Currently only two types of RJ connectors are used for networking: RJ11 and RJ45 (see Figure 18.11). RJ11 connects a traditional telephone to the telephone jack in the wall of your house. It supports up to two pairs of wires, though most phone lines use only one pair. The other pair is used to support a second phone line. RJ11 connectors are primarily used for telephone-based Internet connections (see Chapter 21). RJ45 is the standard for UTP connectors. RJ45 has connections for up to four pairs and is visibly much wider than RJ11. Figure 18.12 shows the position of the #1 and #8 pins on an RJ45 jack.

• Figure 18.11 RJ11 (top) and RJ45 (bottom)

• Figure 18.12 RJ45 pin numbers

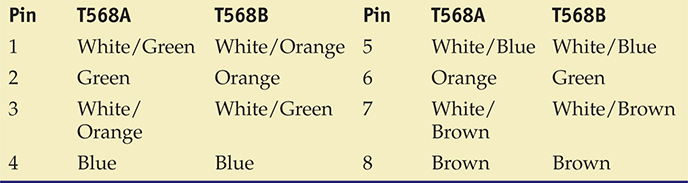

ANSI/TIA has two standards for connecting the RJ45 connector to the UTP cable: T568A and T568B. Both are acceptable. You do not have to follow any standard as long as you use the same pairings on each end of the cable; however, you will make your life simpler if you choose a standard. Make sure that all of your cabling uses the same standard and you will save a great deal of work in the end. Most importantly, keep records!

Tech Tip

Tech Tip

Plenum Versus PVC Cabling

Most workplace installations of network cable go up above the ceiling and then drop down through the walls to present a nice port in the wall. The space in the ceiling, under the floors, and in the walls through which cable runs is called the plenum space. The potential problem with this cabling running through the plenum space is that the protective sheathing for networking cables, called the jacket, is made from plastic, and if you get any plastic hot enough, it creates smoke and noxious fumes.

Standard network cables usually use PVC (polyvinyl chloride) for the jacket, but PVC produces noxious fumes when burned. Fumes from cables burning in the plenum space can quickly spread throughout the building, so you want to use a more fire-retardant cable in the plenum space. Plenum-grade cable is simply network cabling with a fire-retardant jacket and is required for cables that go in the plenum space. Plenum-grade cable costs about three to five times more than PVC, but you should use it whenever you install cable in a plenum space.

Like all wires, the wires in UTP are numbered. A number does not appear on each wire, but rather each wire has a standardized color. Table 18.2 shows the official ANSI/TIA Standard Color Chart for UTP.

Table 18.2 UTP Cabling Color Chart

Ethernet with Alternative Connections

UTP is very popular, but Ethernet, as well as other types of networks, can use alternative cabling that you need to be able to identify. Every CompTIA A+ certified tech needs to know about fiber optic cable and coaxial cable, so let’s start there.

Fiber Optic

Fiber optic cable is a very attractive way to transmit Ethernet network frames. First, because it uses light instead of electricity, fiber optic cable is immune to electrical problems such as lightning, short circuits, and static. Second, fiber optic signals travel much farther, 2000 meters or more (compared with 100 meters on UTP). Many fiber Ethernet networks use 62.5/125 multimode fiber optic cable. All fiber Ethernet networks that use this type of cabling require two strands of fiber (one for sending and one for receiving). Figure 18.13 shows three of the more common connectors used in fiber optic networks. The round connector on the left is called a Straight tip, or ST connector. The square-shaped middle connecter is called a Subscriber connector, or SC connector, and on the far right is a Lucent connector, or LC connector.

• Figure 18.13 Typical fiber optic cables with ST, SC, and LC connectors

Fiber optics are half-duplex, meaning data flows only one way—hence the need for two cables in a fiber installation. With the older ST and SC connectors, you needed two connectors on every fiber connection. Newer connectors like LC are designed to support two fiber cables in one connector, a real space saver.

Light can be sent down a fiber optic cable as regular light or as laser light. Each type of light requires totally different fiber optic cables. Fiber network technologies based on light-emitting diodes (LEDs) generate light signals that use multimode fiber optic cabling. Light entering a multimode fiber enters from many different angles, and these different light rays bounce around the core of the cable. The multiple reflection angles tend to disperse over long distances, so multimode fiber optic cables are used for relatively short connections.

Network technologies that use laser light use single-mode fiber optic cabling. Using laser means that the light rays are aligned, reducing the dispersion over the length of the cable and allowing for phenomenally high transfer rates over long distances. That’s why single-mode fiber optic cabling forms the backbone of the Internet!

There are close to 100 different Ethernet fiber optic cabling standards, with names like 10GBASE-SR and 100GBASE-LR1. The major difference is the speed of the network (there are also some important differences in the way systems interconnect, and so on). If you want to use fiber optic cabling, you need a fiber optic switch and fiber optic network cards.

Fiber networks follow the speed and distance limitations of their networking standard, so it’s hard to pin down precise numbers on true limitations. Multimode overall is slower and has a shorter range than single-mode. A typical multimode network runs at 10 Gbps, though some can go to 100+ Gbps. Distances for multimode runs generally top out at ~600 meters. With single-mode, speed and distance—depending on the standard—can blow multimode away. The record transmission speed in 2021, for example, was 319 terabits per second, and that was over 1800 miles!

Coaxial

Early versions of Ethernet ran on coaxial cable instead of UTP. While the Ethernet standards using coax are long gone, coax lives on, primarily for cable modems and satellite connections. Coax cable consists of a center cable (core) surrounded by insulation. This in turn is covered with a shield of braided cable (see Figure 18.14). The center core actually carries the signal. The shield effectively eliminates outside interference. The entire cable is then surrounded by a protective insulating cover.

• Figure 18.14 Typical coax

Coax cables are rated using an RG name. There are hundreds of RG ratings for coax, but the only two you need to know for the CompTIA A+ exam are RG-59 and RG-6. Both standards are rated by impedance, which is measured in ohms. (Impedance is the effective resistance to the flow of an alternating current electrical signal through a cable.) Both RG-6 and RG-59 have a 75-ohm impedance. Both of these coax cables are used by your cable television, but RG-59 is thinner and doesn’t carry data quite as far as RG-6. The RG rating is clearly marked on the cable.

Coax uses a connector known as an F-type connector. You might already recognize this connector from the back of your cable modem or TV (see Figure 18.15). There is another type of connector called a BNC connector, but it is largely obsolete and you won’t see it on the CompTIA A+ exam.

• Figure 18.15 F-type connector

■ Implementing Ethernet

Regardless of the cabling choice—UTP or fiber—Ethernet networks use a star bus topology. The illustration of a star presented earlier in the chapter in Figure 18.8 doesn’t quite translate into real life, so let’s turn briefly to look at common implementations of Ethernet.

Tech Tip

Tech Tip

Splitters and Coax

Coaxial cable implementations can offer acceptable speeds, topping 2 Gbps in some cases. Using splitters to connect multiple hosts to a single cable, however, negatively affects signal quality, lowering the overall speed of the network.

The Typical LAN

A local area network (LAN) is a group of computers located physically close to each other—no more than a few hundred meters apart at most. A LAN might be in a single room, on a single floor, or in a single building. But I’m going to add that a LAN is almost always a group of computers that are able to “hear” each other when one of them sends a broadcast. A group of computers connected by one or more switches is a broadcast domain (see Figure 18.16), which means that all nodes receive broadcast frames from every other node.

• Figure 18.16 Two broadcast domains—two separate LANs

You can set up a LAN in a small office/home office (SOHO) environment in several ways. The most common way—using wireless technology called Wi-Fi—dispenses with wires altogether. We’ll get there in detail in Chapter 20.

Another option uses the existing electrical network in the building for connectivity. This option, called Ethernet over Power, requires specialized bridges that connect to power outlets. Ethernet over Power has its place in the right situations, and recent innovations have brought speeds up to almost matching Gigabit Ethernet. If you have a computer in a weird place where wireless won’t work and traditional cables can’t reach, try Ethernet over Power.

Structured Cabling

If you want a functioning, dependable, real-world network, you need a solid understanding of a set of standards collectively called structured cabling. These standards, defined by the ANSI/TIA—yes, the same folks who tell you how to crimp an RJ45 onto the end of a UTP cable—give professional cable installers detailed standards on every aspect of a cabled network, from the type of cabling to use to the standards on running cable in walls, even the position of wall outlets.

The CompTIA A+ exams require you to understand the basic concepts involved in installing network cabling and to recognize the components used in a network. The CompTIA A+ exams do not, however, expect you to be as knowledgeable as a professional network designer or cable installer. Your goal should be to understand enough about real-world cabling systems to communicate knowledgeably with cable installers and to perform basic troubleshooting. Granted, by the end of this section, you’ll know enough to try running your own cable (I certainly run my own cable), but consider that knowledge extra credit.

The idea of structured cabling is to create a safe, reliable cabling infrastructure for all of the devices that may need interconnection. Certainly this applies to computer networks, but also to telephone, video—anything that might need low-power, distributed cabling.

You should understand three issues with structured cabling. We’ll start with the basics of how cables connect switches and computers. We’ll then look at the components of a network, such as how the cable runs through the walls and where it ends up. This section wraps up with an assessment of connections leading outside your network.

Cable Basics—A Star Is Born

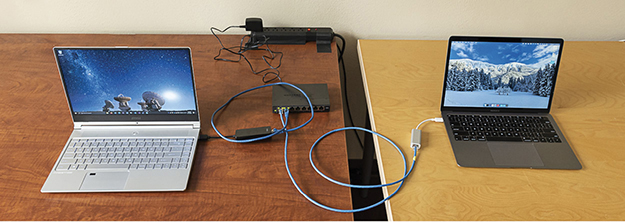

Earlier in this chapter we developed the idea of an Ethernet LAN in its most basic configuration: a switch, some UTP cable, and a few computers—in other words, a typical physical star network (see Figure 18.17).

• Figure 18.17 A switch connected by UTP cable to two computers

No law of physics prevents you from placing a switch in the middle of your office and running cables on the floor to all the computers in your network. This setup works, but it falls apart spectacularly when applied to a real-world environment. Three problems present themselves to the network tech. First, the exposed cables running along the floor are just waiting for someone to trip over them, giving that person a wonderful lawsuit opportunity. Simply moving and stepping on the cabling will, over time, cause a cable to fail due to wires breaking or RJ45 connectors ripping off cable ends. Second, the presence of other electrical devices close to the cable can create interference that confuses the signals going through the wire. Third, this type of setup limits your ability to make any changes to the network. Before you can change anything, you have to figure out which cables in the huge rat’s nest of cables connected to the switch go to which machines. Imagine that troubleshooting nightmare!

“Gosh,” you’re thinking (okay, I’m thinking it, but you should be, too), “there must be a better way to install a physical network.” A better installation would provide safety, protecting the star from vacuum cleaners, clumsy coworkers, and electrical interference. It would have extra hardware to organize and protect the cabling. Finally, the new and improved star network installation would feature a cabling standard with the flexibility to enable the network to grow according to its needs and then to upgrade when the next great network technology comes along. That is the definition of structured cabling.

Structured Cable Network Components

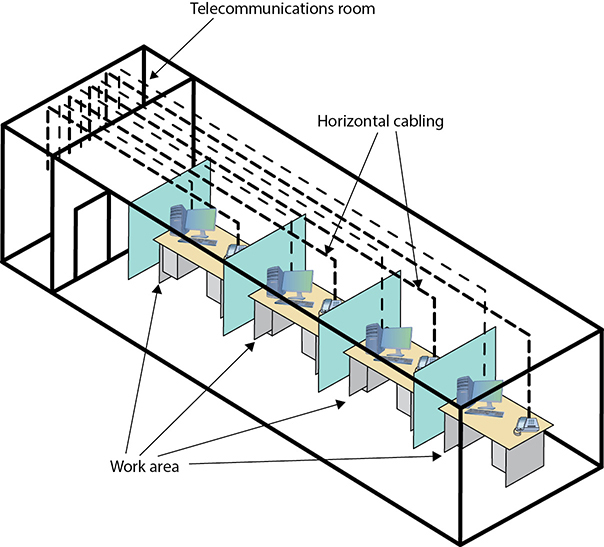

Successful implementation of a basic structured cabling network requires three essential ingredients: a telecommunications room, horizontal cabling, and a work area. Let’s zero in on one floor of a typical office. All the cabling runs from individual workstations to a central location, the telecommunications room. What equipment goes in there—a switch or a telephone system—is not the important thing. What matters is that all the cables concentrate in this one area.

All cables run horizontally (for the most part) from the telecommunications room to the workstations. This cabling is called, appropriately, horizontal cabling. A single piece of installed horizontal cabling is called a run. At the opposite end of the horizontal cabling from the telecommunications room is the work area. The work area is often simply an office or cubicle that potentially contains a workstation and a telephone. Figure 18.18 shows both the horizontal cabling and work areas.

• Figure 18.18 Horizontal cabling and work areas

Each of the three parts of a basic star network—the telecommunications room, the horizontal cabling, and the work area(s)—must follow a series of strict standards designed to ensure that the cabling system is reliable and easy to manage. The cabling standards set by ANSI/TIA enable techs to make sensible decisions on equipment installed in the telecommunications room, so let’s tackle horizontal cabling first, and then return to the telecommunications room. We’ll finish up with the work area.

Horizontal Cabling A horizontal cabling run is the cabling that goes more or less horizontally from a work area to the telecommunications room. In most networks, this cable is a Cat 5e or better UTP, but when you move into structured cabling, the ANSI/TIA standards define a number of other aspects of the cable, such as the type of wires, number of pairs of wires, and fire ratings.

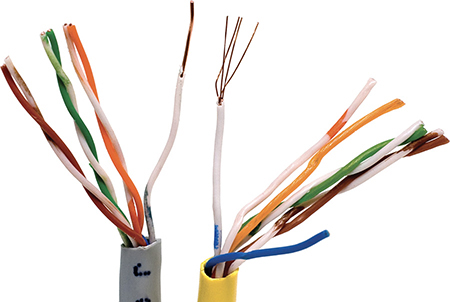

Solid Core Versus Stranded Core All UTP cables come in one of two types: solid core or stranded core. Each wire in solid core UTP uses a single solid wire. With stranded core, each wire is actually a bundle of tiny wire strands. Each of these cable types has its benefits and downsides. Solid core is a better conductor, but it is stiff and will break if handled too often or too roughly. Stranded core is not quite as good a conductor, but it will stand up to substantial handling without breaking. Figure 18.19 shows a close-up of solid and stranded core UTP.

• Figure 18.19 Solid and stranded core UTP

ANSI/TIA specifies that horizontal cabling should always be solid core. Remember, this cabling is going into your walls and ceilings, safe from the harmful effects of shoes and vacuum cleaners. The ceilings and walls enable you to take advantage of the better conductivity of solid core without the risk of cable damage. Stranded cable also has an important function in a structured cabling network, but I need to discuss a few more parts of the network before I talk about where to use stranded UTP cable.

The Telecommunications Room

The telecommunications room is the heart of the basic star. This room is where all the horizontal runs from all the work areas come together. The concentration of all this gear in one place makes the telecommunications room potentially one of the messiest parts of the basic star. Even if you do a nice, neat job of organizing the cables when they are first installed, networks change over time. People move computers, new work areas are added, network topologies are added or improved, and so on. Unless you impose some type of organization, this conglomeration of equipment and cables decays into a nightmarish mess.

Fortunately, the ANSI/TIA structured cabling standards define the use of specialized components in the telecommunications room that make organizing a snap. In fact, it might be fair to say that there are too many options! To keep it simple, we’re going to stay with the most common telecommunications room setup and then take a short peek at some other fairly common options.

Equipment Racks The central component of every telecommunications room is one or more equipment racks. An equipment rack provides a safe, stable platform for all the different hardware components. All equipment racks are 19 inches wide, but they vary in height from two- to three-foot-high models that bolt onto a wall (see Figure 18.20) to the more popular floor-to-ceiling models (see Figure 18.21).

• Figure 18.20 A short equipment rack

• Figure 18.21 A floor-to-ceiling rack

You can mount almost any network hardware component into a rack. All manufacturers make rack-mounted switches that mount into a rack with a few screws. These switches are available with a wide assortment of ports and capabilities. There are even rack-mounted servers, complete with slide-out keyboards, and rack-mounted uninterruptible power supplies (UPSs) to power the equipment (see Figure 18.22).

• Figure 18.22 A rack-mounted UPS

All rack-mounted equipment uses a height measurement known simply as an RU. An RU is 1.75 inches. A device that fits in a 1.75-inch space is called a 1RU; a device designed for a 3.5-inch space is a 2RU; and a device that goes into a 7-inch space is called a 4RU. Most rack-mounted devices are 1RU, 2RU, or 4RU.

Patch Panels and Cables Ideally, once you install horizontal cabling, you should never move it. As you know, UTP horizontal cabling has a solid core, making it pretty stiff. Solid core cables can handle some rearranging, but if you insert a wad of solid core cables directly into your switches, every time you move a cable to a different port on the switch, or move the switch itself, you will jostle the cable. You don’t have to move a solid core cable many times before one of the solid copper wires breaks, and there goes a network connection!

Luckily for you, you can easily avoid this problem by using a patch panel. A patch panel is simply a box with a row of female connectors (ports) in the front and permanent connections in the back, to which you connect the horizontal cables (see Figure 18.23).

• Figure 18.23 Typical patch panels

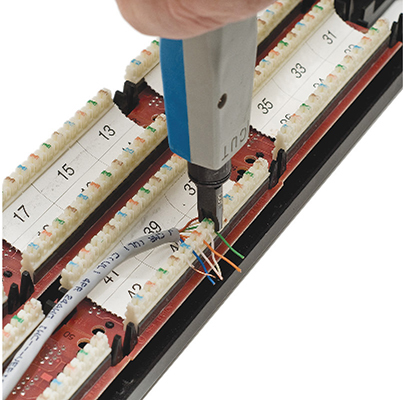

The most common type of patch panel today uses a special type of connector called a punchdown block, or sometimes called a 110-punchdown block. UTP cables connect to a punchdown block using a punchdown tool. Figure 18.24 shows a typical punchdown tool, and Figure 18.25 shows the punchdown tool punching down individual strands.

• Figure 18.24 Punchdown tool

• Figure 18.25 Punching down a punchdown block

The punchdown block has small metal-lined grooves for the individual wires. The punchdown tool has a blunt end that forces the wire into the groove. The metal in the groove slices the cladding enough to make contact.

Not only do patch panels prevent the horizontal cabling from being moved, but they are also your first line of defense in organizing the cables. All patch panels have space in the front for labels, and these labels are the network tech’s best friend! Simply place a tiny label on the patch panel to identify each cable, and you will never have to experience that sinking feeling of standing in the telecommunications room of your nonfunctioning network, wondering which cable is which. If you want to be a purist, there is an official, and rather confusing, ANSI/TIA labeling methodology called ANSI/TIA 606, but many real-world network techs simply use their own internal codes (see Figure 18.26).

• Figure 18.26 Typical patch panels with labels

Patch panels are available in a wide variety of configurations that include different types of ports and numbers of ports. You can get UTP, STP, or fiber ports, and some manufacturers combine several different types on the same patch panel. Panels are available with 8, 12, 24, 48, or even more ports.

UTP patch panels, like UTP cables, come with Cat ratings, which you should be sure to check. Don’t blow a good Cat 6 cable installation by buying a cheap patch panel—get a Cat 6 patch panel! A higher-rated panel supports earlier standards, so you can use a Cat 6 or even Cat 6a rack with Cat 5e cabling. Most manufacturers proudly display the Cat level right on the patch panel (see Figure 18.27).

• Figure 18.27 Cat level on patch panel

Once you have installed the patch panel, you need to connect the ports to the switch through patch cables. Patch cables are short (typically two- to five-foot) UTP cables. Patch cables use stranded rather than solid cable, so they can tolerate much more handling. Even though you can make your own patch cables, most people buy premade ones. Buying patch cables enables you to use different-colored cables to facilitate organization (yellow for accounting, blue for sales, or whatever scheme works for you). Most prefabricated patch cables also come with a reinforced (booted) connector specially designed to handle multiple insertions and removals (see Figure 18.28).

• Figure 18.28 Typical patch cable

Rolling Your Own Patch Cables Although most people prefer simply to purchase premade patch cables, making your own is fairly easy. To make your own, use stranded UTP cable that matches the Cat level of your horizontal cabling. Stranded cable also requires specific crimps, so don’t use crimps designed for solid cable. Crimping is simple enough, although getting it right takes some practice.

Figure 18.29 shows the main tool of the crimping trade: an RJ45 crimper with both a wire stripper, or cable stripper, and wire snips built in. Professional cable installers naturally have a wide variety of other tools as well.

• Figure 18.29 Crimper with built-in stripper and snips

Here are the steps for properly crimping an RJ45 onto a UTP cable. If you have some crimps, cable, and a crimping tool handy, follow along!

1. Cut the cable square using RJ45 crimpers or scissors.

2. Strip off one-half inch of plastic jacket from the end of the cable (see Figure 18.30).

• Figure 18.30 Properly stripped cable

3. Slowly and carefully insert each individual wire into the correct location according to either ANSI/TIA 568A or B (see Figure 18.31). Unravel as little as possible.

• Figure 18.31 Inserting the individual strands

4. Insert the crimp into the crimper and press (see Figure 18.32). Don’t worry about pressing too hard; the crimper has a stop to prevent you from using too much pressure.

• Figure 18.32 Crimping the cable

Figure 18.33 shows a nicely crimped cable. Note how the plastic jacket goes into the crimp. (The extra strands you can see along with the wires are called marker threads or ripcord. The Kevlar strands strengthen the cable and enable installers to rip the sheath off easily.)

• Figure 18.33 Properly crimped cable

A good patch cable should include a boot. Figure 18.34 shows a boot being slid onto a newly crimped cable. Don’t forget to slide each boot onto the patch cable before you crimp both ends!

• Figure 18.34 Adding a boot

After making a cable, you need to test it to make sure it’s properly crimped. I use a handy cable tester, available in any good electronics store, to verify all the individual wires are properly connected and in the correct location (see Figure 18.35).

• Figure 18.35 Typical tester

The Work Area

From a cabling standpoint, a work area is nothing more than a wall outlet that serves as the termination point for horizontal network cables: a convenient insertion point for a workstation and a telephone. (In practice, of course, the term “work area” includes the office or cubicle.) A wall outlet itself consists of one or two female jacks to accept the cable, a mounting bracket, and a faceplate. You connect the workstation to the wall outlet with a patch cable (see Figure 18.36).

• Figure 18.36 Typical work area outlet

The female RJ45 jacks in these wall outlets also have Cat ratings. You must buy Cat-rated jacks for wall outlets to go along with the Cat rating of the cabling in your network. In fact, many network connector manufacturers use the same connectors, often 110 punchdowns, in the wall outlets that they use on the patch panels (see Figure 18.37). These modular outlets significantly increase the ease of installation.

• Figure 18.37 Punching down a modular jack

The last step is connecting the workstation to the wall outlet. Here again, most folks use a patch cable. Its stranded cabling stands up to the abuse caused by moving equipment, not to mention the occasional kick.

The work area may be the simplest part of the structured cabling system, but it is also the source of most network failures. When a user can’t access the network and you suspect a broken cable, the first place to look is the work area.

Going Wide

A wide area network (WAN) is a widespread group of computers connected using long-distance technologies. You connect LANs into a WAN with a magical box called a router (see Figure 18.38). The best example of a WAN is the Internet.

• Figure 18.38 Two broadcast domains connected by a router—a WAN

You can connect multiple smaller networks into a bigger network, turning a group of LANs into one big WAN, but this raises a couple of issues with network traffic. A computer needs some form of powerful, flexible addressing to address a frame so that it goes to a computer within its own LAN or to a computer on another LAN on the same WAN. Broadcasting is also unacceptable, at least between LANs. If every computer saw every frame, the network traffic would quickly spin out of control! Plus, the addressing scheme needs to work so that routers can sort the frames and send them along to the proper LAN. This process, called routing, requires routers and a routing-capable protocol to function correctly.

Routers destroy any incoming broadcast frames by design. No broadcast frame can ever go through a router. This makes broadcasting still quite common within a single broadcast domain, but never anywhere else.

To go beyond a LAN requires a network protocol—a way machines agree to communicate—that can handle routing. That protocol, for the vast majority of networks, is called TCP/IP, and Chapter 19 begins with the details. For now, review the end-of-chapter material and take some practice exams. See you in Chapter 19!

Chapter 18 Review

■ Chapter Summary

After reading this chapter and completing the exercises, you should understand the following facts about networks and resource sharing.

Describe the basic roles of various networked computers

■ A host is any computing device connected to a network. Each networked host fulfills a certain role, such as a Web server serving up Web pages to Web clients via a browser. Network people call anything that one computer might share with another a resource.

■ A local host refers to what’s in front of you, like your macOS workstation. A remote host refers to some other computing device on the network or reachable beyond the network.

■ A networked host that enables you to access a bunch of files and folders is called a file server. The networked host you use to access e-mail messages is called a mail server. A network-connected computer with printer sharing enabled takes on the role of a print server.

Discuss network technologies and Ethernet

■ Networks have one or more client machines with NICs for both defining the nodes and creating frames for sending data to other nodes. Some kind of network cabling or wireless signal connects the nodes together.

■ Each NIC has a unique MAC address that identifies a node. A MAC address is 48 bits long. Frames include the MAC address for both the sender and recipient, some kind of data payload, and a data check. Most frames use a clever mathematical algorithm called a cyclic redundancy check (CRC).

■ To discover the MAC address in Windows, type ipconfig /all at a command prompt and press ENTER. You’ll find the MAC address listed as the “Physical Address” under the Ethernet adapter Local Area Connection category.

■ Most networks today employ some form of Ethernet to define things like frame type and cabling. The vast majority of 100/1000BASE-T and 10GBASE-T networks run on unshielded twisted pair (UTP) cabling. Switches provide the central connection point in the Ethernet star bus topology. Most network cables connect with RJ45 connectors.

■ ANSI/TIA has two standards for connecting the RJ45 connector to the UTP cable: ANSI/TIA 568A (T568A) and ANSI/TIA 568B (T568B).

■ Varieties of UTP include Cat 3, Cat 5, Cat 5e, Cat 6, Cat 6a, Cat 6e, and Cat 7. Each can be plenum-grade or use a PVC jacket.

■ UTP is very popular, but Ethernet can use alternative cabling such as fiber optic cable and coaxial cable. Most fiber Ethernet networks use 62.5/125 multimode fiber optic cable with LEDs to send light signals.

■ Multimode fiber transmits multiple light signals at the same time over shorter distances than single-mode fiber optic cables that use laser light for high transfer rates over long distances. Fiber optic cables use a variety of connectors, such as ST, SC, and LC.

■ Early versions of Ethernet ran on coaxial cable instead of UTP. While the Ethernet standards using coax are long gone, coax lives on primarily for cable modems and televisions.

Describe a typical Ethernet implementation

■ A LAN is a group of computers located physically close to each other—no more than a few hundred meters apart. A group of computers connected by one or more switches is a broadcast domain.

■ Structured cabling standards give professional cable installers detailed standards on every aspect of a cabled network, from the type of cabling to use to standards on running cable in walls and even the position of wall outlets.

■ Successful implementation of a basic structured cabling network requires three essential ingredients: a telecommunications room, horizontal cabling, and a work area. A single piece of installed horizontal cabling is called a run.

■ The central component of every telecommunications room is one or more equipment racks. An equipment rack provides a safe, stable platform for all the different hardware components. All rack-mounted equipment uses a height measurement known simply as a RU, which is 1.75 inches.

■ A patch panel is a box with a row of female connectors (ports) in the front and permanent connections in the back, to which you connect the horizontal cables. The most common type of patch panel today uses a special type of connector called a 110 block. Once you have installed the patch panel, you need to connect the ports to the switch through patch cables.

■ A punchdown tool is used for securing UTP connections to a punchdown block. A cable tech uses a crimper or crimping tool to attach an RJ45 to the end of a UTP cable. A cable tester is used to verify all the individual wires are properly connected and in the correct location.

■ A wide area network (WAN) is a widespread group of computers connected using long-distance technologies. You connect LANs into a WAN with a magical box called a router. Routers destroy any incoming broadcast frames by design. No broadcast frame can ever go through a router.

■ Key Terms

100BASE-TX

1000BASE-T

10GBASE-T

bandwidth

broadcast domain

cable tester

client

coaxial cable

cyclic redundancy check (CRC)

direct burial

equipment rack

Ethernet

F-type connector

fiber optic cable

file server

fileshare

frame

horizontal cabling

host

hub

local area network (LAN)

Lucent connector (LC)

mail server

media access control (MAC) address

network interface controller (NIC)

patch cable

patch panel

plenum

print server

punchdown block

punchdown tool

resource

RG-59

RG-6

RJ11

RJ45

router

RU

run

Subscriber connector SC

segment

server

shielded twisted pair (STP)

solid core

Straight tip (ST)

star bus

stranded core

structured cabling

switch

T568A

T568B

telecommunications room

unshielded twisted pair (UTP)

Web browser

Web server

wide area network (WAN)

work area

■ Key Term Quiz

Use the Key Terms list to complete the sentences that follow. Not all terms will be used.

1. The __________________ version of Ethernet runs at 1000 Mbps.

2. Ethernet cables typically use a(n) __________________ connector.

3. The most common Ethernet topology is __________________.

4. Most Ethernet networks use copper UTP wiring, but a(n) __________________ enables much greater distance between two hosts.

5. Most Ethernet networks have a central box called a(n) __________________.

6. All NICs have a unique identifier called a(n) __________________.

7. Routers enable multiple LANs to connect into a(n) __________________.

8. All the cabling from individual work areas runs via _______________ to a central location.

9. The central location that all cabling runs to is called the _______________.

10. A single piece of installed horizontal cabling is called a(n) _______________.

■ Multiple-Choice Quiz

1. How many bits are in a MAC address?

A. 24

B. 36

C. 48

D. 64

2. What is the minimum Cat level cable required for a 100BASE-TX network?

A. Cat 1

B. Cat 5

C. Cat 5e

D. Cat 6

3. A typical Cat 6 cable uses which connector?

A. RJ11

B. RJ45

C. Plenum

D. PVC

4. Why would you use STP over UTP cabling?

A. Cheaper.

B. Easier to install.

C. Better to avoid interference.

D. They’re interchangeable terms.

5. What kind of frame gets received by all NICs in a LAN?

A. Ethernet

B. Broadcast

C. WAN

D. DNS

6. Safari, Mozilla Firefox, and Google Chrome are all examples of what?

A. Web servers

B. DNS

C. Web browsers

D. IP addresses

7. What is a remote computer providing resources called?

A. Web browser

B. DNS

C. Server

D. Router

8. What is the total amount of data that a network can handle called?

A. Protocol

B. Broadcast

C. Bandwidth

D. Client

9. What do you call the discrete “chunks” of data that networks transmit?

A. Frames

B. Stacks

C. LANs

D. Workgroups

10. John’s boss asks for a recommendation for connecting the company network to a small satellite building about 1 km from the main campus. The company owns the verdant land in between. Given such a scenario, what network technology implementation should John suggest?

A. Ethernet over UTP

B. Ethernet over STP

C. Ethernet over multimode fiber

D. Ethernet over single-mode fiber

11. What is a type of electrical connection often used in telecommunications?

A. Punchdown block

B. Punchdown tool

C. Crimper

D. Router

12. Eddard hands Will a cable. Will hands it back and says, meaningfully, “That’s a nice F-type connector you’ve got there.” What kind of cable does Eddard have?

A. Coaxial

B. Fiber optic

C. STP

D. UTP

13. When connecting a cable run onto a patch panel, which tool should you use?

A. Punchdown tool

B. Crimper

C. TDR

D. Tone generator

14. What is the structured cabling name for the end user’s office space where network computers are set up?

A. Backbone

B. Building entrance

C. Cable drop

D. Work area

15. Which of the following unit designations is used for rack-mounted equipment?

A. A

B. P

C. T

D. RU

■ Essay Quiz

1. Most computers come with onboard NICs. Check out your NIC and determine its fastest speed. Can your NIC support lower speeds as well? Show how you came to this determination.

2. Mike’s office is composed of roughly ten PCs all running 100BASE-TX NICs and a 100BASE-TX switch on Cat 5 cable. He wants to “speed up the network” by going up to 1000BASE-T. Explain to him the process of doing this upgrade and give him your opinion of whether this is a good idea.

3. Sketch a rough draft of your classroom, office, or the room you are in right now. Indicate any doors, windows, closets, lights, plumbing fixtures, desks or tables, and even any visible electrical wall outlets. Then indicate with a large letter X where you would place a new cable drop. Jot down some notes explaining why you would choose the location you did.

Lab Project

• Lab Project 18.1

The PC is not the only device that can connect to an Ethernet network. Do an Internet search or make a run to your local computer store and compile a list of network devices. What did you find? How would they be used?