chapter 20

Wireless Networking

“The wireless telegraph is not difficult to understand. The ordinary telegraph is like a very long cat. You pull the tail in New York, and it meows in Los Angeles. The wireless is the same, only without the cat.”

—ALBERT EINSTEIN

In this chapter, you will learn how to

■ Describe wireless networking components

■ Analyze and explain wireless networking standards

■ Install and configure wireless networks

■ Troubleshoot wireless networks

Wireless networks have been popular for many years now, but unlike wired networks, so much of how wireless works continues to elude people. Part of the problem might be that a simple wireless network is so inexpensive and easy to configure that most users and techs never really get into the hows of wireless. The chance to get away from all the cables and mess and just connect has a phenomenal appeal. The lack of understanding, though, hurts techs when it comes time to troubleshoot wireless networks. Let’s change all that and dive deeply into wireless networking.

Historical/Conceptual

■ Wireless Networking Components

Instead of a physical set of wires running between network nodes, wireless networks use radio waves to communicate. Various kinds of wireless networking solutions have come and gone in the past (including some that used light instead of radio waves), but most of the wireless networks you’ll find yourself supporting these days are wireless LANs (WLANs) based on the IEEE 802.11 wireless Ethernet standard—marketed as Wi-Fi—and on Bluetooth technology.

Wireless networking capabilities of one form or another are built into many modern computing devices. Wi-Fi and Bluetooth capabilities are now common as integrated components, and you can easily add them when they aren’t. Figure 20.1 shows a PCIe Wi-Fi adapter. You can also add wireless network capabilities by using external USB wireless network adapters or wireless NICs, as shown in Figure 20.2.

• Figure 20.1 Wireless PCIe add-on card

• Figure 20.2 External USB wireless NIC

Wireless networking is not limited to PCs. Most smartphones and tablets have wireless capabilities built in or available as add-on options. Figure 20.3 shows a smartphone accessing the Internet over a Wi-Fi connection.

• Figure 20.3 Smartphone with wireless capability

1101

To extend the capabilities of a wireless Ethernet network, such as connecting to a wired network or sharing a high-speed Internet connection, you need a wireless access point (WAP). A WAP centrally connects wireless network devices in the same way that a hub connects wired Ethernet devices. Many WAPs also act as switches and Internet routers, such as the ASUS device shown in Figure 20.4.

• Figure 20.4 ASUS device that acts as wireless access point, switch, and router

Like any other electronic devices, most WAPs draw their power from a wall outlet. More advanced WAPs, especially those used in corporate settings, can also use a feature called Power over Ethernet (PoE). Using PoE, you only need to plug a single Ethernet cable into the WAP to provide it with both power and a network connection. The power and network connection are both supplied by a PoE-capable switch.

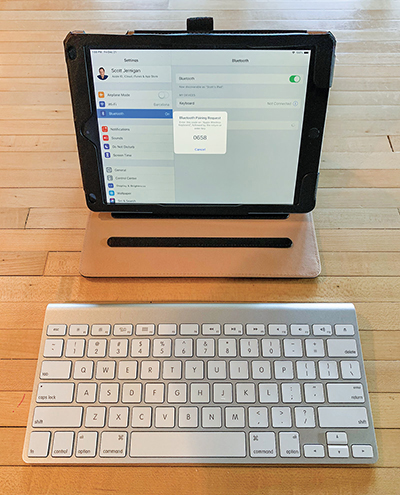

Wireless communication via Bluetooth comes as a built-in option on newer computers and peripheral devices, or you can add it to an older PC via an external USB Bluetooth adapter. All macOS devices—desktop and portable—have Bluetooth. Most commonly these days, you’ll see Bluetooth used to connect a portable speaker to a smartphone, for music on the go, and to connect keyboards to tablets. Figure 20.5 shows a Bluetooth keyboard paired with a Bluetooth-enabled Apple iPad.

• Figure 20.5 Bluetooth keyboard and tablet

Wireless Networking Software

Wireless devices use the same networking protocols and client that their wired counterparts use, and they operate by using the carrier sense multiple access/collision avoidance (CSMA/CA) networking scheme. The collision avoidance aspect differs slightly from the collision detection standard used in wired Ethernet. A wireless device listens in on the wireless medium to see if another is currently broadcasting data. If so, it waits a random amount of time before retrying. So far, this method is exactly the same as the method used by wired Ethernet networks. Because wireless devices have a more difficult time detecting data collisions, however, they offer the option of using the Request to Send/Clear to Send (RTS/CTS) protocol. With this protocol enabled, a transmitting device sends an RTS frame to the receiving device after it determines the wireless medium is clear to use. The receiver responds with a CTS frame, telling the sender that it’s okay to transmit. Then, once the data is sent, the transmitting device waits for an acknowledgment (ACK) from the receiving device before sending the next data packet. This option is very elegant, but keep in mind that using RTS/CTS introduces significant overhead to the process and can impede performance.

In terms of configuring wireless networking software, you need to do very little. Wireless network adapters are plug and play, so any modern version of Windows or macOS immediately recognizes one when it is installed, prompting you to load any needed hardware drivers. You will, however, need a utility to set parameters such as the network name. Modern operating systems include built-in tools for configuring these settings (see Figure 20.6).

• Figure 20.6 Wireless configuration utility in macOS

Wireless Infrastructure

Wireless networks use one or more WAPs to connect the wireless network devices to a wired network segment, as shown in Figure 20.7. A single WAP servicing a given area is called a Basic Service Set (BSS). This service area can be extended by adding more WAPs.

• Figure 20.7 Wireless network with a single WAP

Larger homes, office buildings, and campuses are a whole different beast. They may have more than one WAP wired up to provide good signal coverage throughout the organization. This is called, appropriately, an Extended Basic Service Set (EBSS). They may also lean on devices known as wireless repeaters/extenders that rebroadcast signals from clients and WAPs to help cover dead zones. Organizations can also “wirelessly wire” buildings up to several miles away. Long-range fixed wireless, which uses directional antennas, is a great way to interconnect remote buildings when it’s hard or impractical to physically run cable to them.

Many manufacturers also produce sets of Wi-Fi components (each is a bit like a WAP and a bit like an extender) that collaborate to form a mesh network—with one of these devices serving as the gateway. The key characteristic of a wireless mesh network (WMN) is that the mesh devices act like routers, forwarding traffic for each other. These little mesh networks can improve signal coverage in a house or business that a single router or WAP has trouble covering—with less hassle than if you added more WAPs or extenders.

1102

Wireless Networking Security

One of the classic complaints against wireless networking is that it offers weak security. After all, data packets are floating through the air instead of safely wrapped up inside network cabling—what’s to stop an unscrupulous person with the right equipment from grabbing those packets out of the air and reading that data? We have come a long way since the early days of Wi-Fi. In the past, you could access a wireless network by walking into a WAP’s coverage area, turning on a wireless device, and connecting. These days, it has grown hard to find accidentally open networks, as hardware makers have trended toward using some type of security by default. Still, issues with these well-intentioned defaults are common, so it’s still important to review the settings on new equipment.

Wireless networks use three methods to secure access to the network itself and secure the data being transferred: MAC address filtering, authentication, and data encryption. But before anyone encounters the on-network security, there are some measures we can take to reduce the likelihood our network will be targeted in the first place. Let’s take a look at these practices first, followed by the methods for securing the network itself.

SSID

The service set identifier (SSID) parameter—also called the network name—defines the wireless network. Wireless devices want to be heard, and WAPs are usually configured to announce their presence by broadcasting the SSID to their maximum range. This is very handy when you have several wireless networks in the same area, but a default SSID also gives away important clues about the manufacturer (and maybe even model) of an access point.

Always change the default SSID to something unique and change the password right away. Configuring a unique SSID name and password is the very least that you should do to secure a wireless network. Older default SSID names and passwords are well known and widely available online. While newer models may come with unique SSIDs and passwords, the SSID may still leak information about your hardware—and the generated password may use rules that make it easy to break.

These defaults are intended to make setting up a wireless network as easy as possible but can cause problems in places with a lot of overlapping wireless networks. Keep in mind that each wireless access point in a network needs to be configured with the same unique SSID name. This SSID name is then included in the header of every data packet broadcast in the wireless network’s coverage area. Data packets that lack the correct SSID name in the header are rejected. When it comes to picking a new unique SSID, it’s still good to think about whether the name will make your network a more interesting target or give away details that could help an attacker gain physical or remote access.

Another trick often seen in wireless networks is to tell the WAP not to broadcast the SSID. In theory, people not authorized to access the network will have a harder time knowing it’s there, as it won’t show up in the list of nearby networks on most devices.

In practice, even simple wireless scanning programs can discover the name of an “unknown” wireless network. Disabling the SSID broadcast just makes it harder for legitimate clients to connect. It doesn’t stop bad actors at all—except on a CompTIA A+ exam question.

Access Point Placement and Radio Power

When setting up a wireless network, keep the space in mind; you can limit risk by hiding the network from outsiders. When using an omni-directional antenna that sends and receives signals in all directions, for example, keep it near the center of the home or office. The closer you place it to a wall, the farther away someone outside the home or office can be and still detect the wireless network.

Many wireless access points enable you to adjust the radio power levels of the antenna. Decrease the radio power until you can get reception at the farthest point inside the target network space, but not outside. This will take some trial and error.

Guest Networks

Some WAPs include a guest access feature that makes it easier to set up a network for untrusted users. The CompTIA A+ 1102 objectives mention disabling guest access as a wireless-specific security measure—so be prepared to recognize it as a security measure on the exam. In the real world, be conservative: disable guest access unless you need it. The specifics of this mode can differ, so look into how your device handles guest access if you know you’ll need it—and consider an upgrade if you don’t like what you discover.

Some devices (especially those designed with businesses like bars, cafes, and coffee shops in mind) have a pretty secure guest mode where guests have access to their own SSID—protected with a different password—and you can prevent them from communicating with each other and the rest of your network. Once again, be conservative: if you need guest networks, enable these protections unless you have a specific reason to let guests interact with each other or the rest of your network.

MAC Address Filtering

Most WAPs support MAC address filtering, a method that enables you to limit access to your wireless network based on the physical, hard-wired address of the units’ wireless NIC. MAC address filtering is a handy way of creating a type of “accepted users” list to limit access to your wireless network, but it works best when you have a small number of users. A table stored in the WAP lists the MAC addresses that are permitted to participate in the wireless network. Any data packets that don’t contain a MAC address listed in the table are rejected.

Wireless Security Protocols and Authentication Methods

Wireless security protocols provide authentication and encryption to lock down wireless networks. Wireless networks offer awesome connectivity options, but equally provide tempting targets. Wireless developers have worked very hard to provide techs the tools for protecting wireless clients and communication. Wireless authentication accomplishes the same thing wired authentication does, enabling the system to check a user’s credentials and give or deny him or her access to the network. Encryption scrambles the signals on radio waves and makes communication among users secure.

This section looks at the most recent generations of wireless security protocols, WPA2 and WPA3, as well as typical authentication methods. (See “Wi-Fi Configuration” later in this chapter for the scoop on enterprise authentication installations.)

WPA2 Wi-Fi Protected Access 2 (WPA2) uses the Advanced Encryption Standard (AES) to provide a secure wireless environment. All current WAPs and wireless clients support WPA2. You may encounter older routers with a “backward compatible” mode for first-generation WPA—but at this point I recommend upgrading or replacing WPA-only devices if at all possible.

WPA3 The successor to WPA2 was announced in early 2018. Wi-Fi Protected Access 3 (WPA3) addresses some security and usability issues, including encryption to protect the data of users on open (public) networks.

1101

■ Wireless Networking Standards and Regulations

Most wireless networks use radio frequency (RF) technologies, in particular the 802.11 (Wi-Fi) standards. (Other standards such as Bluetooth hold a much smaller place in today’s market.) These technologies use parts of the RF signal spectrum that were already in use for other purposes, so they are tightly regulated to minimize their impact on those users. To help you gain a better understanding of wireless network technologies, this section provides a brief look at the standards they use and some aspects of how regulations come into play.

IEEE 802.11-Based Wireless Networking

The IEEE 802.11 wireless Ethernet standard, more commonly known as Wi-Fi, defines methods devices may use to communicate via spread-spectrum radio waves. Spread-spectrum broadcasts data in small, discrete chunks over the frequencies available within a certain frequency range.

The 802.11-based wireless technologies broadcast and receive on one of three radio bands: 2.4 GHz, 5 GHz, and 6 GHz. A band is a contiguous range of frequencies that is usually divided up into discrete slices called channels. Over the years, the original 802.11 standard has been extended to 802.11a, 802.11b, 802.11g, 802.11n, 802.11ac, and 802.11ax variations used in Wi-Fi wireless networks. Each of these versions of 802.11 uses one of the two bands, with the exception of 802.11n, which uses one but may use both. Don’t worry; I’ll break this down for you in a moment.

Newer wireless devices typically provide backward compatibility with older wireless devices. If you are using an 802.11n WAP, all of your 802.11g devices can use it. An 802.11ac WAP is backward compatible with 802.11b, g, and n. The exception to this is 802.11a, which requires a 5-GHz radio, meaning only 802.11ac and dual-band 802.11n WAPs are backward compatible with 802.11a devices. The following paragraphs describe the important specifications of each of the popular 802.11-based wireless networking standards. Let’s take a look at Wi-Fi channels first.

Understanding Wi-Fi Channels

Here’s the simple part: each Wi-Fi channel is a little 20-MHz slice of its broader radio band. Unfortunately, you still need to know a good bit more about what channels are and how they operate to configure and manage modern Wi-Fi networks. One of the big reasons for this is that channels are a little bit different between the 2.4-GHz, 5-GHz, and 6-GHz bands—and different countries regulate them differently.

2.4 GHz In the 2.4-GHz band, most countries allow for either 11 or 13 channels, with a big catch—they overlap! Overlapping channels are not so great for performance, so in the United States we’re left with three nonoverlapping channels: 1, 6, and 11. We’re also at the mercy of other nearby networks. If your weird neighbor chooses a weird channel—maybe their favorite number is 8—they can make it harder for everyone else. Be a good neighbor—pick 1, 6, or 11!

5 GHz Thankfully, channels in the 5-GHz band are nonoverlapping. The big catch here, though, is that the number of available channels and the exact ones that are available can differ from country to country. In the United States, we have 25 channels to choose from. You can also (depending on the Wi-Fi standard) “bond” two or four channels into a wide (40 MHz) or ultra-wide (80 MHz) channel, increasing throughput at the expense of making your network more vulnerable to interference. At least for now, 5 GHz is the preferred band—use it if you can!

6 GHz As of this writing, the 6-GHz band is already available for Wi-Fi 6E devices in some countries (including the United States) and is working its way through the regulatory process in others. Its main promise is, of course, less congestion. The new band significantly increases the space available for Wi-Fi networks, giving us many more nonoverlapping channels to spread out over. It’s so much more room, in fact, that it can support bonding eight channels into one super-wide (160 MHz) channel.

802.11a

Despite the “a” designation for this extension to the 802.11 standard, 802.11a was actually on the market after 802.11b. The 802.11a standard differs from the other 802.11-based standards in significant ways. Foremost is that it’s the first Wi-Fi standard to operate in the 5-GHz frequency range. This means devices using this standard are less prone to interference from other devices that use the same frequency range. 802.11a also offers considerably greater throughput than 802.11 and 802.11b, at speeds up to 54 Mbps, though its actual throughput is no more than 25 Mbps in normal traffic conditions. Although its theoretical range tops out at about 150 feet, its maximum range will be lower in a typical office environment.

802.11b

802.11b was the first standard to take off and become ubiquitous in wireless networking. The 802.11b standard supports data throughput of up to 11 Mbps (with actual throughput averaging 4 to 6 Mbps)—on par with older wired 10BASE-T networks—and a maximum range of 300 feet under ideal conditions. In a typical office environment, its maximum range is lower. The main downside to using 802.11b is that it uses a very popular frequency. The 2.4-GHz ISM band is already crowded with baby monitors, garage door openers, microwaves, and wireless phones, so you’re likely to run into interference from other wireless devices.

802.11g

802.11g came out in 2003, taking the best of 802.11a and b and rolling them into a single standard. 802.11g offers data transfer speeds equivalent to 802.11a, up to 54 Mbps, with the wider 300-foot range of 802.11b. More important, 802.11g runs in the 2.4-GHz ISM band, so it is backward compatible with 802.11b, meaning that the same 802.11g WAP can service both 802.11b and 802.11g wireless clients.

802.11n

The 802.11n standard (now also known as Wi-Fi 4) brought several improvements to Wi-Fi networking, including faster speeds and new antenna technology implementations.

The 802.11n specification requires all but hand held devices to use multiple antennas to implement a feature called multiple in/multiple out (MIMO), which enables the devices to make multiple simultaneous connections. With up to four antennas, 802.11n devices can achieve amazing speeds. The official standard supports throughput of up to 600 Mbps, although practical implementation drops that down substantially (to 100+ Mbps at 300+ feet).

Many 802.11n WAPs employ transmit beamforming, a multiple-antenna technology that helps get rid of dead spots—or at least make them not so bad. The antennas adjust the signal once the WAP discovers a client to optimize the radio signal.

Like 802.11g, 802.11n WAPs can run in the 2.4-GHz ISM band, supporting earlier, slower 802.11b/g devices. 802.11n also supports the more powerful so-called dual-band operation. To use dual-band, you need a more advanced (and more expensive) WAP that runs at both 5 GHz and 2.4 GHz simultaneously; some support 802.11a devices as well as 802.11b/g devices.

802.11ac

802.11ac, now also known as Wi-Fi 5, is a natural expansion of the 802.11n standard, incorporating even more streams, wider bandwidth, and higher speed. To avoid device density issues in the 2.4-GHz band, 802.11ac only uses the 5-GHz band. The latest versions of 802.11ac include a new version of MIMO called Multiuser MIMO (MU-MIMO). MU-MIMO gives a WAP the ability to broadcast to multiple users simultaneously. Like 802.11n, 802.11ac supports dual-band operation. Some WAPs even support tri-band operation, adding a second 5-GHz signal to support a lot more 5-GHz connections simultaneously at optimal speeds.

802.11ax

802.11ax—which is also known as high-efficiency wireless (HEW), brings a number of improvements that should help optimize congested networks and reduce power use on client devices. 802.11ax is marketed as both Wi-Fi 6 and Wi-Fi 6E (for extended), and the latter marks a really exciting development in wireless networking—even if the designations are a little slippery. The initial 802.11ax devices, marketed under the Wi-Fi 6 designation, can use both the 2.4-GHz and 5-GHz bands. Newer Wi-Fi 6E devices (technically 802.11ax-2021) use the 2.4-GHz, 5-GHz, and 6-GHz bands. The 6-GHz band can support more nonoverlapping Wi-Fi channels, is not as saturated with existing Wi-Fi networks, and doesn’t suffer as much interference from other devices.

Table 20.1 compares the important differences among modern versions of 802.11x.

Table 20.1 Comparison of Modern 802.11 Standards

Try This!

Try This!

802.11ax Products

802.11ax is the standard for any new Wi-Fi rollout. You need to understand variations, so try this! Head out to a big box electronics retail store, like Microcenter or Best Buy (or go online to Newegg). What variations of 802.11ax products do you see? Note the letters and numbers associated with the products. The base models—the least expensive—might list a speed rating like AX1800. Products listed as AX3000 might cost 30 to 50 percent more, and AX6000 might cost a few times more.

Some Wi-Fi 6E devices are starting to turn up—how many models can you find with AXE speed ratings?

Optimizing Wi-Fi Coverage

Good Wi-Fi provides enough data throughput for your devices to do what you need—and covers every spot you need to connect from. Wireless networking data throughput speeds and coverage depend on many factors, but the most important are the wireless standards in use, the distances involved, the amount of interference present, and the kind of antennas in use.

Depending on the standard used, wireless throughput speeds range from a measly 2 Mbps to a snappy 9+ Gbps. One factor affecting speed is the distance between wireless clients and their access points. Wireless devices dynamically negotiate the top speed at which they can communicate without dropping too many data packets. Speed decreases as distance increases, so the maximum throughput speed is achieved only at extremely close range (less than 25 feet or so). At the outer reaches of a device’s effective range, speed may decrease to around 1 Mbps before it drops out altogether.

Tech Tip

Tech Tip

Checking Signal Strength

You can see the speed and signal strength on your wireless network by looking at the wireless NIC’s status. In Windows, open the Network and Sharing Center, select Change adapter settings, then double-click your wireless NIC to view the status dialog box.

Interference caused by solid objects and other wireless devices operating in the same frequency range—such as microwaves, cordless phones, baby monitors, radar systems, and so on—can reduce both speed and range. So-called dead spots occur when something capable of blocking the radio signal comes between the wireless network clients. Large electrical appliances such as refrigerators block wireless network signals very effectively. Other culprits include electrical fuse boxes, metal plumbing, air conditioning units, and similar objects.

Because of these factors, wireless networking range is difficult to define. This is why you’ll see most descriptions use qualifiers like “around 150 feet” and “about 300 feet.” In Table 20.1 you’ll see the maximum ranges listed as those presented by wireless manufacturers as the theoretical maximum ranges. In the real world, you’ll experience these ranges only under the most ideal circumstances. True effective range is probably about half what you see listed.

Antennas and Transmission Power

These range figures generally assume you’ll set up a WAP with an omni-directional antenna in the center of the area (see Figure 20.8) you want to cover. With an omni-directional antenna, the radio wave flows outward from the WAP. This has the advantage of ease of use—anything within the signal radius can potentially access the network. Most wireless networks, especially in the consumer space, use standard straight-wire dipole antennas to provide omni-directional coverage. Dipole antennas look like a stick, but inside they have two antenna arms or poles aligned on the antenna’s axis; hence the term “dipole.”

• Figure 20.8 Room layout with WAP in the center

Many WAPs have removable antennas that you can replace. To increase the signal in an omni-directional and centered setup, simply replace the factory antennas with one or more bigger antennas (see Figure 20.9). They come in several common flavors. Increasing the size of a dipole will increase its gain evenly in all directions. Directional antennas—such as parabolic dish-type antennas—increase gain (and thus range) in a specific direction and reduce gain in all the other directions. The configuration software on some devices will also allow you to tune the transmission power (regardless of which antenna is in use).

• Figure 20.9 WAP with replacement antenna

In both cases, you should be cautious. A better antenna or higher transmission power may fix your problem, but both are closely regulated. Some antennas may not be legal in your area—or you may not be allowed to use a device with replaceable antennas at all. It may even be possible to increase transmission power to illegal levels and cause trouble for you or your organization.

Long-Range Fixed Wireless

Long-range fixed wireless, which uses directional antennas, is a great way to interconnect remote buildings when it’s hard or impractical to physically run cable to them. Using the right antenna and power level can do more than just extend a network’s range a few hundred feet. Powerful directional antennas enable organizations to provide a remote building or structure with network access (up to several miles away) without having to run cable to it. There isn’t really a specific set of standards for these point-to-point connections, but there are regulatory requirements.

■ Some organizations use specific equipment, jump through Federal Communications Commission (FCC) regulatory hoops, and pay for a license to use a specific frequency. These may use proprietary or existing wireless protocols.

■ Some organizations use normal Wi-Fi standards (and the corresponding unlicensed spectrum) with special equipment.

■ Still others may start with a normal Wi-Fi standard (with unlicensed spectrum) but end up tweaking the software or hardware (deviating from the standard) to solve unique problems that they face.

Just like with regular Wi-Fi networks, the level of transmission power plays a big role in the distance you can communicate over. Signals with a higher transmit power can travel farther and penetrate more obstacles. You want to be like Goldilocks here—use enough power for the receiver to hear you loud and clear, but not so much that you waste tons of electricity or interfere with other users. These point-to-point links also have regulatory requirements that cap the maximum transmission power they can use. Adjusting transmit power will be covered later in the chapter.

Bluetooth

Bluetooth wireless technology (named for tenth-century Danish king Harald Bluetooth) is designed to create small wireless networks preconfigured to do very specific jobs. Some great examples are wearable technology, audio devices such as headsets or automotive entertainment systems that connect to your smartphone, personal area networks (PANs) that link two computers for a quick-and-dirty wireless network, and input devices such as keyboards and mice. Bluetooth is not designed to be a full-function networking solution, nor is it meant to compete with Wi-Fi.

Bluetooth, like any technology, has been upgraded over the years to make it faster and more secure. The first generation (versions 1.1 and 1.2) supports speeds around 1 Mbps. The second generation (2.0 and 2.1) is backward compatible with its first-generation cousins and adds support for more speed by introducing Enhanced Data Rate (EDR), which pushes top speeds to around 3 Mbps. The third generation (3.0 + HS) tops out at 24 Mbps, but this is accomplished over an 802.11 connection after Bluetooth negotiation. The High Speed (+ HS) feature is optional. Instead of continuing to increase top speed, the fourth generation (4.0, 4.1, and 4.2), also called Bluetooth Smart, is largely focused on improving Bluetooth’s suitability for use in networked “smart” devices/appliances by reducing cost and power consumption, improving speed and security, and introducing IP connectivity. The fifth generation (just Bluetooth 5) adds options to increase speed at the expense of range or by changing packet size. Bluetooth 5 adds better support for Internet of Things (IoT) devices, like smart speakers, lights, and so on.

The IEEE organization has made first-generation Bluetooth the basis for its 802.15 standard for wireless PANs. Bluetooth uses a broadcasting method that switches between any of the 79 frequencies available in the 2.45-GHz range. Bluetooth hops frequencies some 1600 times per second, making it highly resistant to interference.

Generally, the faster and farther a device sends data, the more power it needs to do so, and the Bluetooth designers understood a long time ago that some devices (such as a Bluetooth headset) could save power by not sending data as quickly or as far as other Bluetooth devices may need. To address this, all Bluetooth devices are configured for one of three classes that define maximum power usage in milliwatts (mW) and maximum distance:

Bluetooth personal networks are made to replace the snake’s nest of cables that currently connects most PCs to their various peripheral devices—keyboard, mouse, printer, speakers, scanner, and the like—but you probably won’t be swapping out your 802.11-based networking devices with Bluetooth-based replacements anytime soon. Despite this, Bluetooth’s recent introduction of IP connectivity may bring more and more Bluetooth-related traffic to 802.11 devices in the future.

Having said that, Bluetooth-enabled wireless networking is comparable to other wireless technologies in a few ways:

■ Bluetooth is acceptable for quick file transfers where a wired connection (or a faster wireless connection) is unavailable.

■ Bluetooth’s speed and range make it a good match for wireless print server solutions.

As mentioned earlier in the chapter, Bluetooth hardware comes either built into newer portable electronic gadgets such as smartphones or as an adapter added to an internal or external expansion bus. Bluetooth networking is enabled through device-to-device connections or (rarely) through Bluetooth access points. Bluetooth access points are very similar to 802.11-based access points, bridging wireless Bluetooth segments to wired LAN segments.

1102

■ Installing and Configuring Wireless Networking

The mechanics of setting up a wireless network don’t differ much from a wired network. Physically installing a wireless network adapter is the same as installing a wired NIC, whether it’s an internal card, a laptop add-on wireless card, or an external USB device. Simply install the device and let plug and play handle the rest. Install the device’s supplied driver when prompted and you’re practically finished.

The trick is in configuring the wireless network so that only specific wireless clients are able to use it and securing the data that’s being sent through the air.

Wi-Fi Configuration

Typical wireless networks employ one or more WAPs connected to a wired network segment, such as a corporate intranet, the Internet, or both. These networks require that the same SSID be configured on all clients and WAPs.

Most consumer WAPs have an integrated Web server and are configured through a browser-based setup utility. Typically, you open a Web browser on a networked computer and enter the WAP’s default IP address, such as 192.168.1.1, to bring up the configuration page. You need to supply an administrative password, included with your WAP’s documentation, to log in (see Figure 20.10). Most newer WAPs ask you to create an administrative password at installation. Setup screens vary from vendor to vendor and from model to model. Figure 20.11 shows the initial setup screen for an ASUS WAP/router.

• Figure 20.10 Security login for ASUS WAP

• Figure 20.11 ASUS WAP home screen

To make life easier, current WAPs come with a Web-based utility that autodetects the WAP and guides the user through setting up all of its features.

When you purchase a new WAP, there is a pretty good chance the vendor already has updated firmware for it. The chance is even greater if you’ve had your WAP for a while. Before configuring your WAP for your users to access it, you should check for updates. Refer to the section “Software Troubleshooting,” later in the chapter, for more on updating WAP firmware.

Configure the SSID option where indicated. Remember that it’s better to configure a unique SSID than it is to accept the well-known default one. The default may help an attacker identify your hardware and focus on any vulnerabilities it is known to have. Avoid names that include an address, name, number, or other description that would help an attacker locate the physical device.

Channel selection is usually automatic, but you can reconfigure this option if you have particular needs in your organization (for example, if you have multiple wireless networks operating in the same area). Use a wireless analyzer to find the “quietest” channel where you intend to install the WAP and select that channel in the appropriate WAP setup/configuration screen. This provides the lowest chance of interference from other WAPs. Clients automatically search through all frequencies and channels when searching for broadcasted SSIDs.

To increase security even more, use MAC filtering. Figure 20.12 shows the MAC filtering configuration screen for an ASUS WAP. Simply click the Add MAC Address button and enter the MAC address of a wireless device that you wish to allow (or deny) access to your wireless network. Set up encryption by setting the security mode on the WAP and then generating a unique security key or password. Then configure all connected wireless devices on the network with the same credentials. Figure 20.13 shows a security settings WAP properties panel configured for WPA2-Personal wireless security.

• Figure 20.12 MAC filtering configuration screen for an ASUS WAP

• Figure 20.13 Security settings screen for an ASUS WAP

If you’re dealing with ancient equipment and find yourself performing the unseemly task of setting up WEP, you should have the option of automatically generating a set of encryption keys or doing it manually; save yourself a headache and use the automatic method. Select an encryption level—the usual choices are either 64-bit or 128-bit—and then enter a unique passphrase and click the Generate button (or whatever the equivalent button is called on your WAP). Then select a default key and save the settings. The encryption level, key, and passphrase must match on the wireless client or communication will fail. Many WAPs have the capability to export the WEP encryption key data onto a media storage device so you can easily import it on a client workstation, or you can manually configure encryption by using the Windows wireless configuration utility.

WPA encryption (including the preferred WPA3 or WPA2) is configured in much the same way. While it may seem that there are many configuration options, there are effectively two ways to set up WPA/WPA2/WPA3: Personal/Pre-shared Key (PSK) or Enterprise. Personal is the most common for small and home networks (see Figure 20.14). Enterprise is much more complex, requires extra equipment, and is only used in the most serious and secure wireless networks. After selecting the Personal option, there may be “subselections” such as Mixed mode, which allows a WPA3-encrypted WAP to also support WPA2. You may see the term PSK, Pre-Shared Key, or just Personal in the configuration options. If you have the option, choose WPA3 encryption for the WAP as well as the NICs in your network.

• Figure 20.14 Encryption screen on client wireless network adapter configuration utility

Settings such as WPA3 for the Enterprise assume you’ll enable authentication by using something called a RADIUS server (see Figure 20.15). Larger businesses tend to need more security than a single network-wide password can offer. Their networks often require individual users to log in with their own credentials. Security-conscious organizations may even require their users to log in with more than just a username and password. You’ll learn more about this practice, better known as multifactor authentication (MFA), in Chapter 27.

• Figure 20.15 Encryption screen with RADIUS option

To power AAA, the network uses authentication protocols like RADIUS and TACACS+ to authenticate each user with an authentication server. Remote Authentication Dial-In User Service (RADIUS) and Terminal Access Controller Access-Control System Plus (TACACS+) are protocols for authenticating network users and managing what resources they may access.

It can be a little tricky to keep TACACS+ and RADIUS straight. I recommend learning more facts than you’ll probably need to know about them:

■ RADIUS is a completely open standard developed by the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) in a whole boatload of RFCs. RADIUS is partially encrypted and usually uses UDP ports 1812 and 1813. It’s more likely to be interoperable between different device manufacturers.

■ TACACS+ was developed as a proprietary protocol by Cisco, though Cisco has released an “open” description of it so that other companies can also implement it. TACACS+ is fully encrypted and uses TCP port 49. It won’t be as well supported on non-Cisco hardware.

Businesses can allow only people with the proper credentials to connect to their Wi-Fi networks. For home use, select the Personal version of WPA3/WPA2/WPA. Use the best encryption you can. If you have WPA3 or WPA2, use it. If not, use WPA. WEP is configured in much the same way, but it is a terrible choice for a general network. If you can’t upgrade or replace any WEP-only devices, consider setting up a separate WEP network just for them.

With most home networks, you can simply leave the channel and frequency of the WAP at the factory defaults, but in an environment with overlapping Wi-Fi signals, you’ll want to adjust one or both features. To adjust the channel, find the option in the WAP configuration screens and simply change it. Figure 20.16 shows the channel option in an ASUS WAP.

• Figure 20.16 Changing the channel

With multi-band 802.11n, 802.11ac, and 802.11ax WAPs, you can choose whether or not to use the 2.4-GHz, 5-GHz, and 6-GHz bands. In an area with overlapping signals, most of the traffic (at least as of this writing) will be on the 5-GHz frequency. But legacy devices will still be on 2.4 GHz along with other wireless devices such as baby monitors; microwaves also use the 2.4-GHz frequency and can cause a great deal of interference. You can avoid any kind of conflict with your 802.11ac and 802.11ax devices by using the 5-GHz frequency exclusively. Figure 20.17 shows the 2.4-GHz radio being disabled on an 802.11ac WAP.

• Figure 20.17 Disabling the 2.4-GHz radio

Years ago, manufacturers developed wireless LAN controllers to centralize configuration of many dumb WAPs. An organization might have a thousand WAPs but a single software interface for configuring all of them. These days, that configuration interface can be hosted on a local computer or, increasingly, via a cloud-based infrastructure. The latter uses cloud-based network controllers—that’s the CompTIA term. You’re also likely to see such networks referred to as cloud-managed WLANs.

Bluetooth Configuration and Troubleshooting

As with other wireless networking solutions, Bluetooth devices are completely plug and play. Just connect the adapter and follow the prompts to install the appropriate drivers if your OS needs them. Once installed, you’ll need to start the pairing process to enable the devices to create a secure connection—you wouldn’t want every Bluetooth client in range to automatically connect with your smartphone! Figure 20.18 shows a Google Nexus phone receiving a pairing request from an iMac called “mediamac.”

• Figure 20.18 Goggle Nexus receiving a pairing request

Pairing takes a few steps. The first step, of course, is to enable Bluetooth. Some devices, such as Bluetooth headsets, always have Bluetooth enabled because it’s their sole communication method. Others, like a Bluetooth adapter in your computer, may be enabled or disabled in the Network and Sharing Center.

Once enabled, the two devices must be placed into pairing mode. Some devices, like the stereo in my car, continuously listen for a pairing request, while others must be set to pairing (or discovery) mode. The devices in pairing mode will discover each other and agree on a compatible Bluetooth version, speed, and set of features.

The final step of the pairing process, the security component, requires you to confirm your intent to pair the devices. Depending on Bluetooth version and device capabilities, there are a number of different ways this could go; these range from the devices confirming the connection without user input to requiring the user to input a short code on one or both devices. If used, these codes are most often four or six digits, but older devices may differ. Refer to your device’s documentation for specific details on its pairing process.

Done, right? Well, almost. There remains the final step: make sure everything works. Are you getting sound into your Bluetooth headset or speakers? Does the Bluetooth microphone work when making phone calls or recording notes on your smartphone app? Can you stream music from your smartphone to your car stereo? You get the idea. If something isn’t working, it’s time to check for two common problems: unsuccessful/incomplete pairing and configuration issues.

The pairing process is quick and easy to repeat. You may have to delete the pairing from one of the devices first. After re-pairing, test again. If the pairing process never gets started, you have no Bluetooth connectivity. Make sure both devices are on, have Bluetooth enabled, and are in pairing mode. Check battery power in wireless devices and check configuration settings.

If the pairing appears successful but the connection test is not, look for configuration issues. Check microphone input settings and audio output settings. Use any vendor-provided testing and troubleshooting utilities. Keep at it until it works or until you confirm that one or both devices are bad or incompatible.

You’ll need to do a little more than just pair devices to connect to a Bluetooth PAN. This connection is handled by your OS in most cases. Figure 20.19 shows the macOS network configuration for a Bluetooth PAN connected through a Nexus phone.

• Figure 20.19 macOS Bluetooth PAN connected

■ Troubleshooting Wi-Fi

Wireless networks are a real boon when they work right, but they can also be one of the most vexing things to troubleshoot when they don’t. Let’s turn to some practical advice on how to detect and correct wireless hardware, software, and configuration problems.

As with any troubleshooting scenario, your first step in troubleshooting a wireless network is to break down your tasks into logical steps. First, of course, identify the problem, then figure out the scope of the problem. Ask yourself who, what, and when:

■ Who is affected by the problem?

■ What is the nature of their network problem?

■ When did the problem start?

In the formal process of troubleshooting, answering these questions is paramount. The answers to these questions dictate at least the initial direction of your troubleshooting.

So, who’s affected? If all machines on your network—wired and wireless—have lost connectivity, you have bigger problems than a few wireless machines that cannot access the network. Troubleshoot this situation the way you’d troubleshoot any network failure. Once you determine which wireless devices are affected, it’s easier to pinpoint whether the problem lies in one or more wireless clients or in one or more access points.

After you narrow down the number of affected machines, your next task is to figure out specifically what type of error the users are experiencing. If they can access some, but not all, network services, it’s unlikely that the problem is limited to their wireless equipment. For example, if they can browse the Internet but can’t access any shared resources on a server, they’re probably experiencing a permissions-related issue rather than a wireless one.

The last bit of gathering information for this issue is to determine when the problem started. What has changed that might explain your loss of connectivity? Did you or somebody else change the wireless network configuration? For example, if the network worked fine two minutes ago, and then you changed the encryption key or level on the access point, and now nobody can see the network, you have your solution—or at least your culprit! Did your office experience a power outage, power sag, or power surge? Any of these might cause a WAP to fail. And that leads us to the next step of the formal troubleshooting process, establishing a theory of probable cause, which was discussed back in Chapter 1. For now, let’s focus on the specifics of troubleshooting Wi-Fi issues.

Cross Check

Cross Check

Troubleshooting Methodology

Bringing up troubleshooting is a great opportunity to revisit the CompTIA A+ troubleshooting methodology, discussed in Chapter 1. Cross check your memory now and answer these questions. Once you’ve established a theory about what might cause a component not to function properly, what’s next? Once you’ve solved the problem, what’s the absolutely essential last step in the troubleshooting process?

Once you figure out the who, what, and when, you can start troubleshooting in earnest. Typically, your problem is going to center on your hardware, software, connectivity, or configuration.

Hardware Troubleshooting

Wireless networking hardware components are subject to the same kind of abuse and faulty installation as any other hardware component. Troubleshooting a suspected hardware problem should bring out the technician in you.

Open Windows Device Manager and look for an error or conflict with the wireless adapter. If you see a big exclamation point next to the device, you have a driver error. A downward-facing arrow next to the device indicates that it has been disabled. Enable it if possible or reinstall the device driver as needed.

If you don’t see the device listed at all, perhaps it is not seated properly or plugged in all the way. These problems are easy to fix. Just remove and reinstall the device.

Software Troubleshooting

Because you’ve already checked to confirm your hardware is using the correct drivers, what kind of software-related problems are left? Two things come immediately to mind: the wireless adapter configuration utility and the WAP’s firmware version.

As I mentioned earlier, some wireless devices won’t work correctly unless you install the vendor-provided drivers and configuration utility before plugging in the device. This is particularly true of wireless USB devices. If you didn’t do this already, go into Device Manager and uninstall the device, then start again from scratch.

By the time you unpack your new WAP, there’s a good chance its firmware is already out of date. Out-of-date firmware could manifest in many ways. Your WAP may enable clients to connect, but only at such slow speeds that they experience frequent timeout errors; you may find that, after a week, your clients can connect but have no Internet access until you reboot the WAP; Apple devices may have trouble connecting or running at advertised speeds. The important thing here is to be on the lookout for strange or erratic behavior.

Manufacturers regularly release firmware updates to fix issues just like these—and many more—so it’s good to update the access point’s firmware. For older WAPs, go to the manufacturer’s Web site and follow the support links until you find the latest firmware version. You’ll need your device’s exact model number and hardware version, as well as the current firmware version—this is important, because installing the wrong firmware version on your device is a guaranteed way to render it useless! Modern WAPs have built-in administration pages to upload the newly downloaded firmware. Some can even check for firmware updates and install them. Because there are too many WAP variations to cover here, always look up the manufacturer’s instructions for updating the firmware and follow them to the letter.

Connectivity Troubleshooting

Properly configured wireless clients should automatically and quickly connect to the desired SSID, assuming both the client and WAP support the correct bands. If this isn’t taking place, it’s time for some troubleshooting. Most wireless connectivity problems come down to either an incorrect configuration (such as an incorrect password) or low signal strength. Without a strong signal, even a properly configured wireless client isn’t going to work. Wireless clients use a multi-bar graph (usually five bars) to give an idea of signal strength: zero bars indicates no wireless connectivity and five bars indicates maximum signal. Weak signals or a very busy network (especially with older, closer clients) can both result in slow network speeds, high latency, and intermittent wireless connectivity.

Whether configuration or signal strength, the process to diagnose and repair is similar to what you’d do for a wired network. Since very few wireless NICs have link lights, you can almost always jump right to checking the Wi-Fi configuration utility. Figure 20.20 shows Windows 10 displaying the link state and signal strength.

• Figure 20.20 Windows 10’s wireless configuration utility

The link state defines the wireless NIC’s connection status to a wireless network: connected or disconnected. If your link state indicates that your computer is currently disconnected, you may have a problem with your WAP. If your signal is too weak to receive, you may be out of range of your access point or there may be a device causing interference.

You can fix these problems in a number of ways. Because Wi-Fi signals bounce off of objects, you can try small adjustments to your antennas or WAP placement to see if the signal improves. If your WAP has removable antennas, you can swap out the standard antenna for ones with more transmit power. You can relocate the PC or access point, or locate and move the device causing interference.

You can also run into trouble if there are just too many devices on your network. This can be especially troublesome if you also have some devices that are using old Wi-Fi standards that tie up your WAPs for longer to satisfy the same request than a device using a newer standard would. If you know the network is busy, it might be worth seeing if the problem disappears during off-hours—or even try limiting the number of clients. If you know you’ve got old Wi-Fi devices around, replacing them or moving them off onto a separate WAP (that uses a different channel) can increase network performance for everyone.

Other wireless devices that operate in the same frequency range as your Wi-Fi can cause external interference as well. Look for wireless telephones, intercoms, and so on as possible culprits. One fix for interference caused by other Wi-Fi devices is to change the channel your network uses. Another is to change the channel the offending device uses, if possible. If you can’t change channels, try moving the interfering device to another area or replacing it with a different device.

Configuration Troubleshooting

With all due respect to the fine network techs in the field, the most common type of wireless networking problem is misconfigured hardware or software. That’s right—the dreaded user error! Given the complexities of wireless networking, this isn’t so surprising. All it takes is one slip of the typing finger to throw off your configuration completely. The things you’re most likely to get wrong are the SSID and security configuration, though dual-band routers have introduced some additional complexity.

Verify SSID configuration (for any bands in use) on your access point first, and then check on the affected wireless devices. With most wireless devices, you can use any characters in the SSID, including blank spaces. Be careful not to add blank characters where they don’t belong, such as trailing blank spaces behind any other characters typed into the name field.

In some situations, clients that have always connected to a WAP with a particular SSID may no longer be able to connect. The client may or may not give an error message indicating “SSID not found.” There are a couple possible explanations for this and they are easy to troubleshoot and fix. The simplest culprit is that the WAP is down—easy to find and easy to fix. On the opposite end of the spectrum is a change to the WAP. Changing the SSID of a WAP will prevent the client from connecting. The fix can be as simple as changing the SSID back or updating the client configuration. A client may not connect to a new WAP, even if it has the same SSID and connection configuration as the previous one. Simply delete the old connection profile from the client and create a new one.

If you’re using MAC address filtering, make sure the MAC address of the client that’s attempting to access the wireless network is on the list of accepted users. This is particularly important if you swap out NICs on a PC, or if you introduce a new device to your wireless network.

Check the security configuration to make sure that all wireless clients and access points match. Mistyping an encryption key prevents the affected client from talking to the wireless network, even if your signal strength is 100 percent! Remember that many access points have the capability to export encryption keys onto a thumb drive or other removable media. It’s then a simple matter to import the encryption key onto the PC by using the wireless NIC’s configuration utility. Remember that the encryption level must match on access points and clients. If your WAP is configured for WPA2, all clients must also use WPA2.

Chapter 20 Review

■ Chapter Summary

After reading this chapter and completing the exercises, you should understand the following about wireless networking.

Describe wireless networking components

■ The wireless radio wave networks you’ll find yourself supporting these days are wireless LANs based on the IEEE 802.11 wireless Ethernet standard, marketed as Wi-Fi, and on Bluetooth technology.

■ Wireless networking capabilities of one form or another are built into many modern computing devices. Wi-Fi and Bluetooth capabilities are almost ubiquitous as integrated components and, where lacking, can easily be added by using USB or PCIe adapters. Many smartphones and tablets have wireless capabilities built in or available as add-on options.

■ To extend the capabilities of a wireless Ethernet network, such as connecting to a wired network or sharing a high-speed Internet connection, you need a wireless access point. A WAP centrally connects wireless network devices in the same way that a switch connects wired Ethernet PCs.

■ Like any other electronic devices, most WAPs draw their power from a wall outlet. More advanced WAPs, especially those used in corporate settings, can also use Power over Ethernet (PoE) provided by a PoE switch or PoE injector.

■ Wireless devices use the same networking protocols and client that their wired counterparts use, and they operate by using the CSMA/CA (not to be confused with the CSMA/CD from wired Ethernet) networking scheme, where devices check before broadcasting. Wireless devices also use the RTS/CTS protocol. When enabled, a transmitting device that determines that the wireless medium is clear to use sends an RTS frame to the receiving device. The receiver responds with a CTS frame, telling the sender that it’s okay to transmit. Then, once the data is sent, the transmitting device waits for an acknowledgment (ACK) from the receiving device before sending the next data packet.

■ Modern operating systems include built-in tools for configuring wireless network settings.

■ Wireless networks use one or more WAPs to connect wireless devices to a wired network segment. A single WAP serving a given area is called a Basic Service Set (BSS). Larger organizations add more WAPs to extend coverage, creating an Extended BSS (EBSS).

■ Wireless network coverage can also be extended with wireless repeaters/extenders that rebroadcast signals, using long-range fixed wireless to interconnect remote buildings, or making use of mesh networking devices.

■ Early networks lacked great security, but these days it’s hard to find accidentally open networks, because hardware makers tend to provide security right out of the box. Wireless devices want to be heard, and WAPs are usually configured to announce their presence by broadcasting the SSID to their maximum range.

■ Always change the default SSID and password to something unique.

■ Place antennas and tune transmission power to provide good coverage inside your space without spilling outside to tempt would-be leachers.

■ Ensure unneeded guest networks are disabled.

■ Most WAPs support MAC address filtering, a method that enables you to limit access to your wireless network based on the physical, hard-wired address of the unit’s wireless network adapter.

■ Wireless security protocols provide authentication and encryption to lock down wireless networks.

■ Modern wireless networks and devices are secured with Wi-Fi Protected Access 2 (WPA2) or WPA3 encryption.

■ Wi-Fi supports three communication bands: 2.4 GHz, 5 GHz, and 6 GHz. Each band is divided up into slices called channels. The exact size and number of channels available depend on both the band in use and local regulations.

Analyze and explain wireless networking standards

■ 802.11a differs from the other 802.11-based standards in significant ways. Foremost, it’s the first Wi-Fi standard to operate in a different frequency range, 5 GHz, so 802.11a devices are less prone to interference. 802.11a also offers considerably greater throughput than 802.11 and 802.11b at speeds up to 54 Mbps, though its actual throughput is no more than 25 Mbps in normal traffic conditions. Although its theoretical range tops out at about 150 feet, its maximum range will be lower in a typical office environment.

■ The 802.11b standard supports data throughput of up to 11 Mbps—on par with older wired 10BASE-T networks—and a range of up to 300 feet under ideal conditions.

■ The 802.11g standard offers data transfer speeds equivalent to 802.11a, up to 54 Mbps, with the wider 300-foot range of 802.11b. Because 802.11g is backward compatible with 802.11b, the same 802.11g WAP can service both 802.11g and 802.11b wireless clients.

■ 802.11n (also known as Wi-Fi 4) ups the speed even more to 100+ Mbps and extends the range to greater than 300 feet by using MIMO (multiple in/multiple out) with extra antennas. You can also configure it to use the less crowded 5-GHz band if you are using a dual-mode WAP.

■ 802.11ac (also known as Wi-Fi 5) is a natural expansion of the 802.11n standard, incorporating even more streams, wider bandwidth, and higher speed. To avoid device density issues in the 2.4-GHz band, 802.11ac only uses the 5-GHz band. The latest versions of 802.11ac include a new version of MIMO called Multiuser MIMO (MU-MIMO).

■ 802.11ax (also known as High Energy Wireless and marketed as both Wi-Fi 6 and Wi-Fi 6E [for extended; 802.11ax-2021]) includes many improvements for optimizing congested networks and reducing power use on client devices. Wi-Fi 6 devices can use the 2.4-GHz and 5-GHz bands, while Wi-Fi 6E can use 2.4 GHz, 5 GHz, and 6 GHz.

■ Many factors affect Wi-Fi speed and coverage. Depending on the standard used, wireless throughput speeds range from a measly 2 Mbps to a snappy 9+ Gbps. Wireless devices dynamically negotiate the top speed at which they can communicate without dropping too many data packets. Speed decreases with range before dropping out. Interference caused by solid objects and other wireless devices can reduce speed and range—and even create dead spots.

■ A wireless device’s true effective range is probably about half the theoretical maximum listed by the manufacturer.

■ Range figures generally assume the WAP uses an omni-directional antenna and is placed in the center of the area you want to cover—with coverage radiating out in all directions. This usually entails a straight dipole antenna, which looks like a stick (but contains two antenna poles). Many WAPs have removable antennas, and you can extend range by swapping out an antenna for a more powerful one. Directional antennas increase gain/range in a specific direction. You can also often tune the power level of the device.

■ Long-range fixed wireless uses directional antennas to communicate with a remote building or structure without running cable. These point-to-point connections can use licensed radio bands (if you jump through the hoops of paying for a license) or use the unlicensed Wi-Fi bands.

■ Bluetooth wireless technology is designed to create small wireless networks called personal area networks (PANs) that link computers to peripheral devices such as printers, input devices such as keyboards and mice, and even consumer electronics such as cell phones, home stereos, televisions, home security systems, and so on. Bluetooth is not designed to be a full-function networking solution.

Install and configure wireless networks

■ The mechanics of setting up a wireless network don’t differ much from a wired network. Physically installing a wireless network adapter is the same as installing a wired NIC, whether it’s an internal expansion card, a laptop add-on wireless card, or an external USB device. Simply install the device and let plug and play handle the rest.

■ Most consumer WAPs have an integrated Web server and are configured through a browser-based setup utility. Typically, you open a Web browser on a networked computer and enter the WAP’s default IP address to bring up the configuration page and supply an administrative password, included with your WAP’s documentation, to log in. Most newer WAPs ask you to create an administrative password at installation.

■ Set up WEP encryption—if that’s your only option—by turning encryption on at the WAP and then generating a unique security key. Then configure all connected wireless clients on the network with the same key information. WPA/WPA2/WPA3 encryption is configured in much the same way. You may be required to input a valid username and password to configure encryption when using WPA/WPA2/WPA3.

■ Enterprise networks may use RADIUS or TACACS+ to authenticate users with an authentication server and manage which network resources they may access.

■ You may have to tune the channel selection (or restrict band usage on multi-band 802.11n, 802.11ac, and 802.11ax WAPs) to avoid interference caused by other networks in crowded Wi-Fi environments.

■ As with other wireless networking solutions, Bluetooth devices are completely plug and play. Just connect the adapter and follow the prompts to install the appropriate drivers if your OS needs them. Once installed, you’ll need to start the pairing process to enable the devices to create a secure connection. You’ll need to do a little more than just pair devices to connect to a Bluetooth PAN. This connection is handled by your OS in most cases.

Troubleshoot wireless networks

■ As with any troubleshooting scenario, your first step should be to figure out the scope of your wireless networking problem. Ask yourself who, what, and when. Gathering this information helps you focus your initial troubleshooting on the most likely aspects of the network. The six steps of the CompTIA troubleshooting methodology (presented in Chapter 1) can be especially helpful as well when troubleshooting wireless networks.

■ Hardware troubleshooting for Wi-Fi devices should touch on the usual hardware process. Go to Device Manager and check for obvious conflicts. Check the drivers to make sure you have them installed and up to date. Make certain you have proper connectivity between the device and the PC. If you see a big exclamation point next to the device, you have a driver error. A downward-facing arrow next to the device indicates that it has been disabled. Enable it if possible or reinstall the device driver as needed.

■ Software troubleshooting involves checking Device Manager for the latest drivers first. Manufacturers regularly release firmware updates to fix hardware- and software-related wireless WAP issues, so it’s good to update the access point’s firmware.

■ You can fix signal and interference problems in a number of ways. Because Wi-Fi signals bounce off of objects, you can try small adjustments to your antennas to see if the signal improves. You can swap out the standard antenna for one or more higher-gain antennas. You can relocate the PC or access point, or locate and move the device causing interference. If the network is too crowded, moving some devices off (or upgrading them, if they use older standards) may improve throughput for everyone else. You can also change the wireless channel your network uses. Another solution is to change the channel the offending device may be using.

■ For “SSID not found” errors, ensure that the WAP is not down, and then check for a change to the WAP. Changing the SSID of a WAP will prevent the client from connecting.

■ If you’re using MAC address filtering, make sure the MAC address of the client that’s attempting to access the wireless network is on the list of accepted users.

■ Check the security configuration to make sure that all wireless clients and access points match. The encryption level must match on access points and wireless clients. If your WAP is configured for WPA2, all clients must also use WPA2.

■ Key Terms

802.11a

802.11ac

802.11ax

802.11b

802.11g

802.11n

Advanced Encryption Standard (AES)

Bluetooth

carrier sense multiple access/collision avoidance (CSMA/CA)

dipole antenna

IEEE 802.11

long-range fixed wireless

MAC address filtering

personal area network (PAN)

Power over Ethernet (PoE)

radio frequency (RF)

service set identifier (SSID)

Wi-Fi

Wi-Fi 6

Wi-Fi 6E

Wi-Fi Protected Access 2 (WPA2)

Wi-Fi Protected Access 3 (WPA3)

wireless access point (WAP)

wireless repeater/extender

■ Key Term Quiz

Use the Key Terms list to complete the sentences that follow. Not all terms will be used.

1. A technology for setting up wireless PANs and connecting to some peripherals is called __________________.

2. Establishing a unique __________________ or network name helps ensure that only wireless network devices configured similarly are permitted access to the network.

3. The wireless Ethernet standard that operates at a maximum of 54 Mbps on the 2.4-GHz frequency is __________________.

4. __________________ entails using directional antennas.

5. The 802.11 protocol is more commonly known as __________________.

6. Of the common wireless encryption protocols, __________________ is the least secure that has not been deprecated.

7. The first wireless Ethernet standard that uses the 5-GHz frequency is __________________.

8. The marketing designation __________________ indicates support for 6-GHz Wi-Fi networks.

9. The __________________ determines the name of a wireless network.

10. 802.11 implements __________________, which proactively avoids network packet collisions rather than simply detecting them when they occur.

■ Multiple-Choice Quiz

1. Which of the following is a reason to use the 6-GHz band for Wi-Fi?

A. It is closely regulated and licensed for human safety.

B. It enables better outdoor signal coverage than the other bands.

C. There aren’t as many 6-GHz Wi-Fi networks.

D. There aren’t as many regulations as in the other bands.

2. What device centrally connects wireless network devices in the same way that a hub or switch connects wired Ethernet PCs?

A. Bluetooth adapter

B. Wireless NIC

C. SSID

D. WAP

3. What is the approximate range of an 802.11n network?

A. ~1000 ft

B. ~300 ft

C. ~150 ft

D. ~500 ft

4. Which of these encryption methods used on wireless networks is the most secure?

A. WEP

B. WPS

C. TACACS+

D. WPA2

5. What can limit wireless connectivity to a list of accepted users based on the hard-wired address of their wireless NIC?

A. Encryption

B. MAC filtering

C. MIMO

D. WEP

6. Which wireless standard combines the longest range with the most throughput?

A. 802.11a

B. 802.11ac

C. 802.11ax

D. 802.11n

7. Personal area networks are created by what wireless technology?

A. Bluetooth

B. WAP

C. Wi-Fi

D. Cellular

8. What type of antenna could enable you to extend a house’s Internet access to a workshop a mile away?

A. Beamforming

B. Dipole

C. Fiber optic

D. Directional

9. What standard gained a speed boost in its second version with Enhanced Data Rate technology?

A. Bluetooth

B. Wi-Fi

C. Wi-Fi 6E

D. Cellular

10. Which of these Wi-Fi security protocols is the least secure and is easily hacked?

A. WEP

B. WAP

C. AES

D. WPA2

11. What is a cheap and easy way to extend the range of a WAP?

A. Upgrade the antenna.

B. Buy a WAP that advertises a longer range.

C. You can’t easily boost range.

D. Upgrade the wireless NICs.

12. What is the technical name of a wireless network?

A. SSID

B. BSSID

C. SSD

D. PoE

13. Which encryption protocol offers the best security?

A. Hi-Encrypt

B. WEP

C. WPA

D. WPA2

14. Which of the following 802.11 standards functions only on the 5-GHz band?

A. 802.11g

B. 802.11ac

C. 802.11ax

D. 802.11n

15. Which of the following can extend a PoE connection up to 100 meters?

A. CSMA/CD

B. Power over Ethernet injector

C. Wi-Fi analyzer

D. Advanced Encryption Standard

■ Essay Quiz

1. You are enrolled in a writing class at the local community college. This week’s assignment is to write on a technical subject. Write a short paragraph about each of the wireless standards that can reach theoretical speeds of 54 Mbps or greater.

2. Write a few paragraphs describing the pros and cons of both wired and wireless networks. Specifically, compare the speed of 1 Gbps to the 802.11ax standard. Then conclude with a statement of your own personal preference. You’ll need to draw on information you found in this chapter and in Chapter 18.

Lab Projects

• Lab Project 20.1

An agricultural company wants to try to extend wireless from the office to three buildings spread out over several miles of flat, open land. The buildings are two, four, and six miles from the main office. Using the Internet, research what equipment is needed to create a long-range point-to-point wireless connection, and try to find the cheapest way to connect each building. After you have done sufficient research, prepare a table like the following:

• Lab Project 20.2

You have been tasked with expanding your company’s wireless network. Your IT manager asked you to create a presentation that explains wireless routers and their functions. She specifically said to focus on the 802.11ac and 802.11ax wireless network standards. Create a brief but informative PowerPoint presentation that includes comparisons of these two technologies. You may include images of actual WAPs from vendor Web sites as needed, being sure to cite your sources. Include any up-to-date prices from your research as well.