chapter 21

The Internet

[Cueball sitting at computer]

Voice outside frame: Are you coming to bed?

Cueball: I can’t. This is important.

Voice: What?

Cueball: Someone is WRONG on the Internet.

—XKCD, “DUTY CALLS”

In this chapter, you will learn how to

■ Explain how the Internet works

■ Connect to the Internet

■ Use Internet application protocols

■ Troubleshoot an Internet connection

The Internet was once the domain of academics and technologists, but over the past few decades it has mushroomed into a dense fabric that interconnects literally billions of devices—including devices used mainly by people and devices that just do their own thing. The Internet was once a place we went intentionally. I’d come home from a long day at work and sit down to be transported into the fantasy universe of a game that I could play with millions of other gamers around the world. I still enjoy escaping into a good game—but these days the Internet itself is the nervous system of modern society!

This chapter covers the skills you need as a tech to help connect devices to the Internet. It starts with a brief section on how the Internet works, along with the concepts of connectivity, and then it goes into the specifics of the protocols and software that you use to make the Internet work for you (or for your client). Finally, you’ll learn how to troubleshoot a bad Internet connection. Let’s get started!

Historical/Conceptual

■ How the Internet Works

Thanks to the Internet, people can communicate with one another over vast distances, often in the blink of an eye. As a tech, you need to know how computers communicate with the larger world for two reasons. First, knowing the process and pieces involved in the communication enables you to troubleshoot effectively when that communication goes away. Second, you need to be able to communicate knowledgeably with a network technician who comes in to solve a more complex issue.

You probably know that the Internet joins gajillions of devices together to form the largest network on earth, but not many folks know much about how these computers are organized. Most importantly, the Internet is a network of networks. Some of these networks are large, and others are tiny. Some of these networks belong to families or small shops, while others belong to hospitals, local governments, Internet service providers (ISPs), and of course technology giants like Amazon, Apple, Google, Microsoft, and so on.

Deep inside the infrastructure that makes up the Internet, the largest of these networks are stitched together into a globe-spanning fabric by a piece of equipment called a backbone router. Backbone routers sit along long-distance high-speed fiber optic networks called backbones and connect to more than one other backbone router, creating a framework for transferring massive amounts of data. Figure 21.1 illustrates the decentralized and interwoven nature of the Internet.

•Figure 21.1 Internet backbone connections between cities

The key reason for interweaving the backbones of the Internet was to provide alternative pathways for data if one or more of the routers went down. If Jane in Houston sends a message to her friend Polly in New York City, for example, the shortest path between Jane and Polly in this hypothetical situation might be: Jane’s message originates at Rice University in Houston, bounces to Emory University in Atlanta, flits through Georgetown University in Washington, DC, and then zips into SUNY in New York City (see Figure 21.2). Polly happily reads the message and life is great. The Internet functions as planned.

•Figure 21.2 Message traveling from Houston to NYC

But what would happen if the entire southeastern United States were to experience a huge power outage and Internet backbones in every state from Maryland to Florida were to go down? Jane’s message would fail to go through, so the Rice computers would resend Jane’s message. Meanwhile, the routers would update their list of good routes and then attempt to reroute the message to functioning nodes—say, Rice to University of Chicago, to University of Toronto, and then to SUNY (see Figure 21.3). It’s all in a day’s work for the highly redundant and adaptable Internet. At this point in the game, the Internet simply cannot go down fully—barring, of course, a catastrophe of Biblical proportions.

•Figure 21.3 Rerouted message from Houston to NYC

TCP/IP: The Common Language of the Internet

As you know from all the earlier chapters in this book, hardware alone doesn’t cut it in the world of computing. You need software to make the machines run and create an interface for humans. The Internet is no exception. TCP/IP provides the basic software structure for communication on the Internet.

Because you spent a good deal of Chapter 19 working with TCP/IP, you should have an appreciation for its adaptability and, perhaps more importantly, its extensibility. TCP/IP provides the addressing scheme for computers that communicate on the Internet through IPv4 addresses (such as 192.168.4.1) or IPv6 addresses (like 2603:b23c:d:a421:edcd:9c82:41a4:7a5b). As a suite of protocols, though, TCP/IP is much more than just an addressing system. TCP/IP provides the framework and common language for the Internet. And it offers a phenomenally wide-open structure for creative purposes. Programmers can write applications built to take advantage of the TCP/IP protocols and their features. The cool thing about TCP/IP is that it’s proven to be an astonishingly fruitful foundation limited only by the imagination of the programmers building on top of it.

At this point, you have an enormous functioning network. All the backbone routers connect redundant, high-speed backbone lines, and TCP/IP enables communication and services for building applications that enable humans and machines to interface across vast distances. What’s left? Oh, of course: How do you tap into this great network and partake of its goodness?

Internet Service Providers

Most of us connect to the Internet by renting access through a company called an Internet service provider (ISP). ISPs come in all sizes. Comcast, the cable television provider, has multiple huge-capacity connections into the Internet, enabling its millions of customers to connect from their local machines and access the Internet. Contrast Comcast with Electric Power Board (EPB) of Chattanooga, an ISP in Chattanooga, Tennessee (see Figure 21.4), which bills itself as “the world’s fastest internet.” Unfortunately, EPB only offers its blazing 10 gigabit fiber connections to the lucky citizens of Chattanooga.

•Figure 21.4 Electric Power Board (EPB) of Chattanooga home-based Internet page

Connection Concepts

Connecting to an ISP requires two things to work perfectly: hardware for connectivity, such as a modem and a working cable line, and software, such as protocols to govern the connections and the data flow (all configured in the OS) and applications to take advantage of the various TCP/IP services. Once you have a contract with an ISP to grant you access to the Internet, they will either send a technician to your house or mail you a package containing any hardware and software you might need. With most ISPs, a DHCP server will provide your computer with the proper TCP/IP information. As you know from Chapter 19, the router to which you connect at the ISP is often referred to as the default gateway. Once your computer is configured, you can connect to the ISP and get to the greater Internet. Figure 21.5 shows a standard computer-to-ISP-to-Internet connection. Note that various protocols and other software manage the connectivity between your computer and the default gateway.

•Figure 21.5 Simplified Internet connectivity

Cross Check

Cross Check

Networking Boxes

Although non-techs tend to call every networking box they see a “router,” good techs know that networking boxes serve a variety of purposes. Now is a good time to cross-check your memory of Chapters 18 and 19 and answer these questions. What’s a switch? What’s a router? When should you use a switch or a router?

1101

■ Connecting to the Internet

Computers commonly connect to an ISP through their wired or wireless router. If the customer purchased the router, it will have an Ethernet connection to a box (often—but not always—called a modem) that interconnects it with the ISP’s network. If the customer leased a router from their ISP, it will often have a built-in modem. The connection to the ISP could use one of many wired or wireless technologies—the modem takes care of the details. Let’s take a look at all these various connection options, and then finish this section by discussing basic router configuration and sharing an Internet connection with other computers.

DSL

Digital subscriber line (DSL) connections to ISPs use a standard telephone line with special equipment on each end to create always-on Internet connections.

Service levels for DSL can vary widely. At the low end of the spectrum, speeds are generally in the single digits—less than 1 Mbps upload and around 3 Mbps download. Where available, more recent xDSL technologies can offer competitive broadband speeds measured in tens or hundreds of megabits per second.

DSL requires little setup from a user standpoint. A tech comes to the house to install the DSL receiver, often called a DSL modem (see Figure 21.6), and possibly hook up a wireless router.

•Figure 21.6 A DSL receiver

Even if you skip the tech and have the installation equipment mailed to you, all you have to do is plug a couple of special filters in and call your ISP. These DSL microfilters remove the high-pitch screech of the DSL signal, enabling traditional landline phones and fax machines to operate correctly. The receiver connects to the telephone line and the computer (see Figure 21.7). The tech (or the user, if knowledgeable) then configures the DSL modem and router (if there is one) with the settings provided by the ISP, and that’s about it! Within moments, you’re surfing the Web. You don’t need a second telephone line. You don’t need to wear a special propeller hat or anything. The only kicker is that your house has to be within a fairly short distance from a main phone service switching center (central office). This distance can depend on the DSL variant and can range from several hundred feet to around 18,000 feet.

•Figure 21.7 DSL connection

Cable

Cable offers a different approach to high-speed Internet access, using regular cable TV cables to serve up lightning-fast speeds. It offers faster service than most DSL connections, with upload speeds from 5 to 35+ Mbps and download speeds ranging anywhere from 15 to 2000+ Mbps. Cable Internet connections are theoretically available anywhere you can get cable TV.

Cable Internet connections start with an RG-6 or RG-59 cable coming into your house. The cable connects to a cable modem that then connects to a small home router (you will often see the modem and router combined into a single box today) or your network interface card (NIC) via Ethernet. Figure 21.8 shows a typical cable setup using a router.

•Figure 21.8 Cable connection

Fiber

In the past, high costs meant that only those with money to burn could enjoy the super-fast speeds of a fiber connection. Subsequently, DSL providers developed very popular fiber-to-the-node (FTTN) and fiber-to-the-premises (FTTP) services that provide Internet (and often Internet and telephone services over the same connection), making them head-to-head competitors with the cable companies. Entrants like Google Fiber and local municipalities have added momentum to the fiber rollout.

With FTTN, the fiber connection runs from the provider to a box somewhere in your neighborhood. This box connects to your home or office using normal coaxial or Ethernet cabling. FTTP runs from the provider straight to a box in your home or office, using fiber the whole way. You might expect this box (which does convert data to and from light) to be called a fiber modem—but it has a better name: an optical network terminal (ONT). The ONT has an input for the fiber connection, and an Ethernet or coax connection for a router which then provides wireless (or Ethernet) to connect your computers to the Internet.

One popular fiber-based service is AT&T Internet (formerly called U-verse), which generally offers download speeds from 10 to 100 Mbps and upload speeds from 1 to 20 Mbps for their FTTN service. AT&T Fiber is their FTTP service that gives you 300 Mbps to 5 Gbps for download and upload (see Figure 21.9). Verizon’s Fios service is the most popular and widely available FTTP service in the United States, providing upload and download speeds ranging from 300 Mbps to 1 Gbps. Google Fiber, for its part, offers a 1- and 2-Gbps upload/download service.

•Figure 21.9 A Frontier FiOS FTTP ONT in my closet

Wi-Fi

Wi-Fi (or 802.11 wireless) is so prevalent that it’s the way many of us get to the Internet. Wireless access points (WAPs) designed to serve the public abound in coffee shops, airports, fast-food chains, and bars. Even some cities provide partial to full Wi-Fi coverage.

We covered 802.11 in detail in Chapter 20, so there’s no reason to repeat the process of connecting to an access point. Do remember that most open networks do not provide any level of encryption, meaning it’s easy for a bad guy to monitor your connection and read everything you send or receive.

WISP

Another form of wireless Internet service—appropriately called wireless Internet service provider (WISP)—works a little bit like a traditional wired broadband Internet service with a twist: the last segment or two uses a point-to-point long-range fixed wireless connection. The customer just needs to install an antenna provided by the WISP—usually on the outside of their house—and they are online. Since WISPs don’t have to run cable to every home they cover, they can often provide cheaper service—or provide service in areas where other broadband providers aren’t.

Cellular

Who needs computers when you can get online with any number of mobile devices? Okay, there are plenty of things a phone or tablet can’t do, but with the latest advances in cellular data services, your mobile Internet experience will feel a lot more like your home Internet experience than it ever has before. The most common way to access the Internet with a cellular connection—which the CompTIA A+ 1101 exam objectives also refer to as wireless WAN (WWAN)—is directly through a mobile device. It’s far from the only way, though! Let’s look at the technology first, and then consider how to put it to use.

Cellular data services have gone through a number of names over the years, so many that trying to keep track of them and place them in any order is extremely challenging. In an attempt to make organization somewhat clearer, the cellular industry developed a string of marketing terms using the idea of generations: first-generation devices are called 1G, second-generation are 2G, followed by 3G, 4G, and 5G. On top of that, many technologies use G-names such as 2.5G to show they’re not 2G but not quite 3G. You’ll see these terms on your phones, primarily if you’re not getting the best speed possible (see Figure 21.10). Marketing folks tend to bend and flex the definition of these terms in advertisements, so you should always read more about the device and not just its generation.

•Figure 21.10 iPhone connecting over 5G

The first generation (1G) of cell phone data services was analog and not at all designed to carry packetized data. It wasn’t until the early 1990s that two fully digital technologies called the Global System for Mobile Communications (GSM) and code division multiple access (CDMA) came into wide acceptance. GSM evolved into GPRS and EDGE, while CDMA introduced EV-DO. GPRS and EDGE were 2.5G technologies, while EV-DO was true 3G. Standards with names like UTMS, HSPA+, and HSDPA have brought GSM-based networks into the world of 3G and 3.5G. These mobile data services provide modest real-world download speeds of a few (generally under 10) Mbps.

We’re now at the tail end of the fourth generation. Devices and networks using Long Term Evolution (LTE) technology rolled out worldwide in the early 2010s and now dominate wireless services. As early as 2013, for example, LTE already had ~20 percent market share in the United States, and even higher in parts of Asia. The numbers have only grown since then. Marketed as and now generally accepted as a true 4G technology, LTE networks feature theoretical speeds of up to 1 Gbps download and 100 Mbps upload (see Figure 21.11).

•Figure 21.11 Real-world LTE speed test

The fifth-generation cellular networks—appropriately called 5G—saw a big development push in 2018, and rollout started in 2019. The IMT-2020 specifications call for speeds up to 20 Gbps—blazingly fast—but real-world speeds are often a far cry from this (and may vary a lot depending on the carrier and location).

Both 4G and 5G can readily replace wired network technology anywhere there’s sufficient cellular data coverage. Most of the big cellular carriers offer home service—a standalone cellular modem you can plug into the wall and connect to your router. You can also use a mobile hotspot—a device that connects via cellular and shares its Internet access—when you’re away from home.

Hotspots can be dedicated devices or simply a feature of a modern smartphone. (See Chapter 24 for a deep dive into smartphone technologies.) Using a hotspot to connect to the Internet is often called tethering. Figure 21.12 shows an iPhone in hotspot mode with tethering instructions for Wi-Fi, Bluetooth, and USB.

•Figure 21.12 Tethering in iOS

Satellite

Satellite connections to the Internet get the data beamed to a satellite dish on your house or office. Traditionally, providers such as HughesNet and Viasat have used a small number of satellites in very high-altitude geostationary orbits to cover absolutely massive sections of the globe with about 25 Mbps download and 3 Mbps upload speeds. It also means you need to make sure the satellite dish points toward the satellite (generally toward the south if you live in the northern hemisphere)—so you’ll usually want it professionally installed with line-of-sight to the satellite. A coax cable runs from the dish to your satellite modem. The satellite modem has an RJ-45 connection, which you may then connect directly to your computer or to a router.

As both satellites and the costs to develop and launch them have shrunk, there’s been a surge of interest in satellite Internet services that use a very large number of satellites in low Earth orbit. This kind of service depends on having enough satellites passing over a given area to provide continuous service, but Starlink (one of the most visible providers) is already delivering several times more download and upload bandwidth where it offers service.

Getting your Internet from the stars has some downsides. The first significant issue is the upfront cost of the dish and installation. The signal can also degrade or drop entirely in foul weather such as rain and snow. Many providers also have usage limits, to ensure a small number of users don’t degrade the service for everyone on the same satellite. Finally, there’s the distance the signal must travel to the satellite. Although low-orbit constellations can provide a level of latency—how long it takes the signal to make the round-trip—that’s just a little worse than wired broadband, traditional high-orbit service comes with several hundred milliseconds of latency. This is usually unnoticeable for general Web use, but can make any real-time activity such as gaming or voice/video chat difficult in the best of circumstances.

Connection to the Internet

So you went out and signed up for an Internet connection. Now it’s time to get connected. You basically have two choices:

1. Connect a single computer to your Internet connection

2. Connect a network of computers to your Internet connection

Connecting a single computer to the Internet is easy. If you’re using wireless, you connect to the WAP using the provided information, although a good tech will always go through the proper steps described in Chapter 20 to protect the wireless network. If you choose to go wired, you run a cable from whatever type of box is provided to the computer.

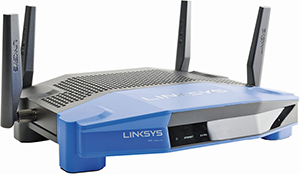

If you want to connect multiple computers using wired connections, make sure your router has a built-in switch with enough ports. Several manufacturers offer robust, easy-to-configure routers that are a nice upgrade from the routers provided by the ISP. These boxes require very little configuration and provide firewall protection between the primary computer and the Internet, which you’ll learn more about in Chapter 27. All it takes to install one of these routers is simply to plug your computer into any of the LAN ports on the back, and then to plug the cable from your Internet connection into the port labeled Internet or WAN.

There are hundreds of perfectly fine choices for SOHO (small office/home office) routers (see Figure 21.13 for an example). Most have four Ethernet switch ports for wired connections and one or more Wi-Fi radios for any wireless computers you may have. All SOHO routers use a technology called Network Address Translation (NAT) to perform a little network subterfuge: It presents an entire LAN of computers to the Internet as a single machine. It effectively hides all of your computers and makes them appear invisible to other computers on the Internet. All anyone on the Internet sees is your public IP address. This is the address your ISP gives you, while all the computers in your LAN use private addresses that are invisible to the world. NAT therefore acts as a firewall, protecting your internal network from probing or malicious users on the outside.

•Figure 21.13 Common SOHO router with Wi-Fi

Basic Router Configuration

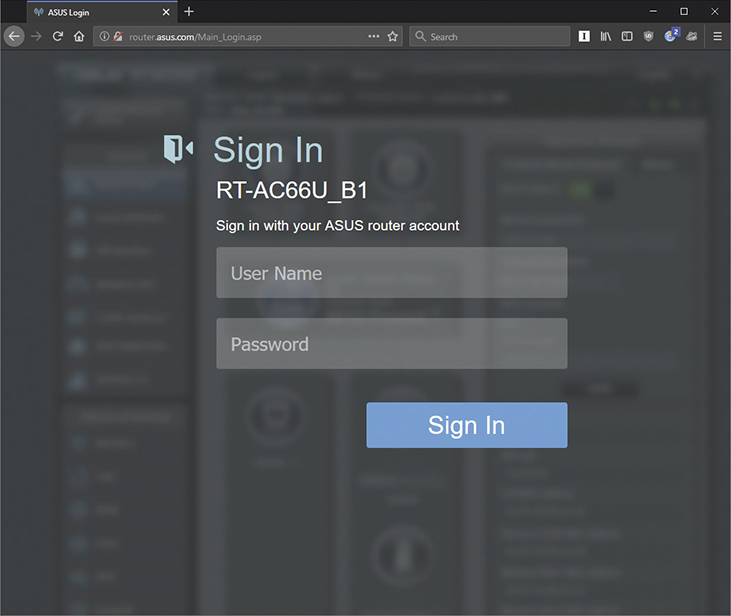

SOHO routers require very little in the way of configuration and in many cases will work perfectly (if unsafely) right out of the box. In some cases, though, you may have to deal with a more complex network that requires changing the router’s settings. The vast majority of these routers have built-in configuration Web pages that you access by typing the router’s IP address into a browser. The address varies by manufacturer, so check the router’s documentation. If you typed in the correct address, you should then receive a prompt for a username and password, as in Figure 21.14. As with the IP address, the default username and password vary depending on the model/manufacturer. Once you enter the correct credentials, you will be greeted by the router’s configuration pages (see Figure 21.15). From these pages, you can change any of the router’s settings.

•Figure 21.14 Router asking for username and password

•Figure 21.15 Configuration home page

Now we’ll look at a few of the basic settings that CompTIA wants you to know. (We’ll discuss more advanced settings in Chapter 27 that help keep your network and the computers on it secure while they use services available over the Internet.)

UPnP A lot of networking devices designed for the residential space use a feature called universal plug and play (UPnP) to find and connect to other UPnP devices. Common UPnP devices include things like media servers and printers. Since this feature enables seamless interconnectivity at the cost of somewhat lowered security, leave it disabled (as shown in Figure 21.16) if you don’t need it.

•Figure 21.16 Disabled UPnP option

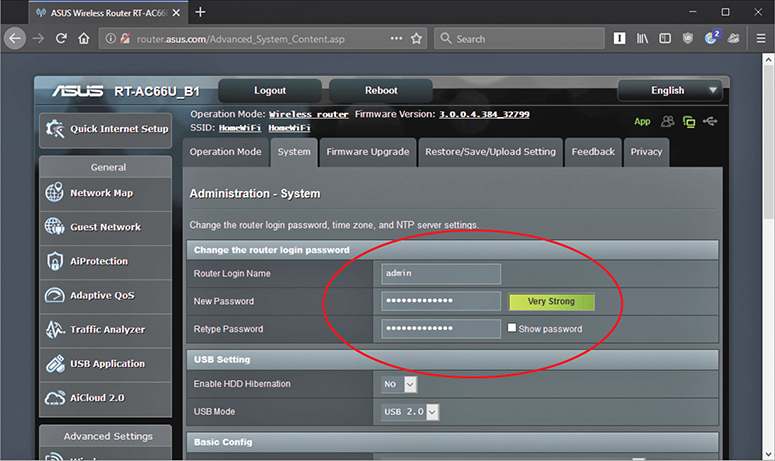

Changing Default Credentials Since all routers have a default username and default password combination that gives you access to the configuration screen, anyone who has access to your LAN or WLAN can easily gain access to the router and change its settings. One of the first things you should do is change these default login credentials as shown in Figure 21.17.

•Figure 21.17 Changing the password

Setting Static IP Addresses In most cases, when you plug in the router’s Internet connection, it receives an IP address (from your ISP) using DHCP just like any other computer. Of course, this means that your Internet IP address can change from time to time. This isn’t a problem for most people, but some home users and businesses may want a stable IP address to host their own sites and services. Most ISPs enable you to order a static IP address (for an extra monthly charge) and then either supply you with a preconfigured router or give you IP settings to manually enter into your router. My router has an Internet Setup configuration section where I enter the settings that my ISP has provided (see Figure 21.18). Remember to change your connection type from Automatic/DHCP to Static IP to enter the new addresses.

•Figure 21.18 Entering a static IP address

Updating Firmware

Routers are just like any other computer in that they run software—and software has bugs, vulnerabilities, and other issues that sometimes require updating. The router manufacturers call these “firmware updates,” and either the router will automatically install them or the manufacturer will make them available for manual install either through the router’s administration interface or on the manufacturer’s Web site for easy download.

If the firmware update is available directly through your router’s administration interface, a firmware update may be a few clicks away. If not, download the latest firmware from the manufacturer’s Web site to your computer. Then enter the router’s configuration Web page and find the firmware update screen. On my router, it looks like Figure 21.19. From here, just follow the directions and click Upgrade (or your router’s equivalent). A quick word of caution: Unlike a Windows update, a firmware update gone bad can brick your router. In other words, it can render the hardware inoperable and make it as useful as a brick sitting on your desk. This rarely happens, but you should keep it in mind when doing a firmware update.

•Figure 21.19 Firmware update page

■ Using the Internet

The Internet is constantly teeming with activity, but it doesn’t actually do a whole lot all by itself. Once you’ve established a connection to the Internet, you need applications to get anything done. If you want to surf the Web, you need an application called a Web browser, such as Mozilla Firefox, Google Chrome, Microsoft Edge, or Apple Safari. If you want to communicate with people, you might need an e-mail client or one of the many real-time communication applications like Discord, Skype, Slack, Telegram, Teams, Zoom—and tons more. If you want to watch streaming video, you’ll need Netflix or one from its always-growing list of competitors.

Underneath the hood, these applications all use one or more application protocols to communicate with the servers that power them. The CompTIA A+ exams expect you to know about a few of the many thousands of applications and application protocols that you might encounter on the Internet—or in your own networks—so this section starts with an overview of the application protocols you may see on the exam, and then looks at how those protocols manifest in different kinds of applications. That’s a lot of ground to cover, so buckle up!

Internet Application Protocols

It’s possible for application developers to invent their own proprietary protocol for their application and servers to communicate with—but creating a good, secure protocol is a lot of work. Most application developers turn to well-known application protocols that anyone can use. Web browsers use the Hypertext Transfer Protocol (HTTP) to transfer Web pages and related resources. E-mail clients use Post Office Protocol 3 (POP3) or Internet Message Access Protocol (IMAP) to receive e-mail and Simple Mail Transfer Protocol (SMTP) to send e-mail.

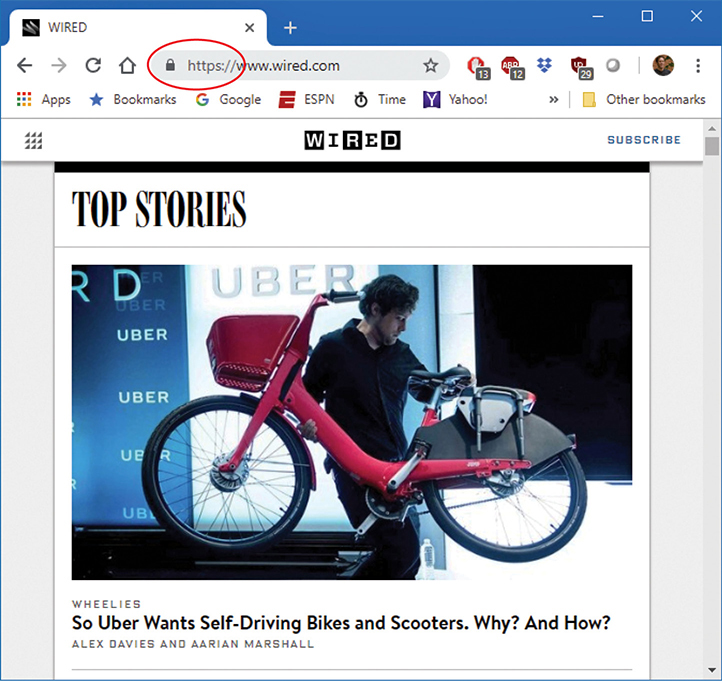

Each protocol has its own rules and its own port numbers. Here’s an example: most sensitive information sent over the Web (things like credit card information and phone numbers) are sent using an encrypted version of HTTP called Hypertext Transfer Protocol Secure (HTTPS). Although HTTPS looks a lot like HTTP from the point of view of a Web browser, HTTPS uses its own port: 443. It’s easy to tell if a Web site is using HTTPS because the Web address starts with the protocol—note the https shown in Figure 21.20, instead of just http.

•Figure 21.20 A secure Web page

Though there are tens of thousands of application protocols in existence, lucky for you, CompTIA only wants you to understand the following commonly used application protocols (except SFTP and SIP, which CompTIA doesn’t list in the objectives but I’ve added for completeness):

■ World Wide Web (HTTP and HTTPS)

■ E-mail (POP3, IMAP, and SMTP)

■ Telnet

■ SSH

■ FTP/SFTP

■ Remote Desktop Protocol (RDP)

■ VoIP (SIP)

In addition to the application protocols we see and use daily, there are hundreds, maybe thousands, of application protocols that run behind the scenes, taking care of important jobs to ensure that the application protocols we do see run well. You’ve encountered a number of these hidden application protocols back in Chapter 19. Take DNS. Without DNS, you couldn’t type www.google.com in your Web browser and end up at the right address. DHCP is another great example. You don’t see DHCP do its job, but without it, any computers relying on DHCP won’t receive IP addresses.

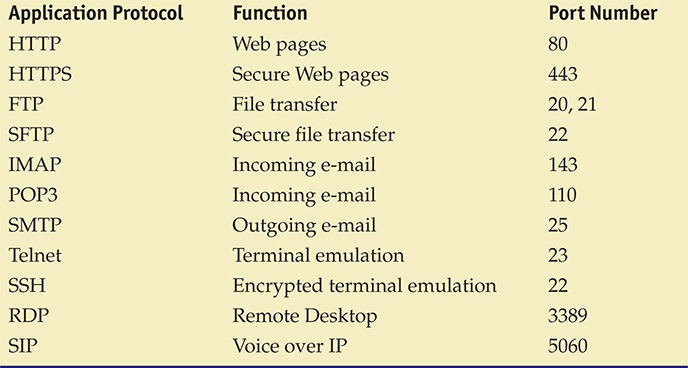

In order to differentiate the application protocols you see from the application protocols you don’t see, I’m going to coin the term “utility protocol” to define any of the hidden application protocols. So, using your author’s definition, HTTP is an application protocol and DNS is a utility protocol. All TCP/IP protocols use defined ports, require an application to run, and have special settings unique to that application. You’ll look at several of these services and learn how to configure them. As a quick reference, Table 21.1 lists the names, functions, and port numbers of the application protocols CompTIA would like you to know (except, again, SFTP and SIP). Table 21.2 does the same for utility protocols.

Table 21.1Application Protocol Port Numbers

Table 21.2 Utility Protocol Port Numbers

You’ve already encountered a few of these protocols in earlier chapters. The rest of this section will explore many of the different ways to use the Internet and how the rest of these protocols enable those uses.

1102

Browsing the Web

If some shadowy character in a trench coat stepped out of an alley, handed you a USB drive, and told you to run the program it holds, I hope you’d be too cautious to just plug it into the same computer you use for work, online shopping, or banking. It may be a surprise if you’ve never looked under the hood of a Web browser, but what they do isn’t that much different!

A Web browser downloads code, images, and other resources from servers more or less anywhere in the world and then runs that code on your own computer in order to render the Web site. To download these resources, the browser interacts with these Web servers using the HTTPS protocol on port 443 and HTTP on port 80. Figure 21.21 shows the home page of my company’s Web site, https://www.totalsem.com, in Mozilla Firefox. Where is the server located? Does it matter? It could be in a closet in my office or in a huge data center in Northern Virginia.

•Figure 21.21 Mozilla Firefox showing a Web page

Because people use browsers for lots of really important things—like banking and shopping—it’s really important to make sure they’re secure. Let’s take a closer look at what browsers are, where to get them, and a few ways to use them to stay safe.

Installing Browsers

These days, almost all operating systems come with a browser or a simple way to install one. Because we need to be able to trust browsers, it’s super important to be cautious about where you get them from. An illegitimate copy of Google Chrome could look and smell just like the real thing—but be subtly compromised to give attackers access to your data or system. Make sure you only install browsers from trusted sources such as your operating system provider’s official app store or package manager, or the browser vendor’s own Web site.

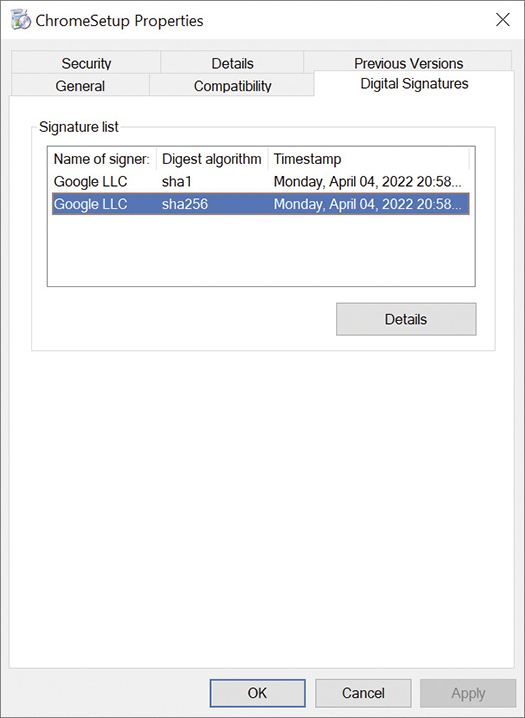

Your operating system’s app store or package manager should automatically help ensure (but not guarantee) that the software you install is legitimate. If you download the installer on your own, it’s a good idea to take some additional steps to verify the installer before you run it. The specifics differ, but whether it’s done by an app store, package manager, or by hand, this process always involves one or more cryptographic techniques such as hashing and/or code signing.

Many (but not all) software developers will publish their own checksums for all of the software they release. A checksum is created by running that file through a cryptographic hash function, which outputs a digital fingerprint for a file. We can repeat this same hashing process after we download the files to confirm that the fingerprints match.

Code signing takes this idea one step further. The developer registers their own digital certificate with whoever develops the OS, app store, or package manager—and uses the certificate to sign the software they release. Your OS, app store, or package manager can then verify these signatures to ensure that the software was released by the registered developer (and not, say, someone who guessed their password). You can check these signatures yourself in Windows by right-clicking the file, selecting Properties, and switching to the Digital Signatures tab (see Figure 21.22).

•Figure 21.22 Digital signatures (signed by Google, LLC) for a Google Chrome installer

Browser Extensions and Plug-ins

Most modern browsers support additional extensions or plug-ins that modify or extend how they work. There are all kinds of extensions out there, but some common examples are extensions that restyle Web pages, save articles for reading later, block ads, translate pages, and so on. Each browser generally has one trusted source for extensions—either an extension store just for the browser or the operating system’s app store. Figure 21.23 shows the Gesturefy extension for Firefox, which enables me to quickly navigate the Web by holding down a key and wiggling my mouse!

•Figure 21.23 Gesturefy extension settings in Mozilla Firefox

Password Managers

Back in ye olde days we just had to remember or write down the passwords to all of the different online accounts we needed to log on to. That didn’t work very well—it made things very easy for hackers. These days, it’s a good idea to use a password manager, which helps you out by storing your passwords and the accounts or Web sites they’re associated with. You can find standalone password managers, password manager extensions for browsers (shown in Figure 21.24), and even password managers directly built into modern browsers.

•Figure 21.24 Adding a password to the Bitwarden password manager extension in Safari

Password managers aren’t perfect. Using one can increase the chances that someone with physical or remote access to one of your devices can log on to any of your accounts, for example. But using a password manager also makes it easier to use a different, very strong password for every account. A good password manager also helps you identify passwords that are weak, used for more than one service, or have been found in databases of stolen credentials. A good password manager will also make it easy for you to generate strong passwords.

Secure Connections and Sites

Any time you browse the Web—but especially when you’re doing sensitive things like logging in to accounts, transferring funds, or making purchases—it’s best to make sure you have a secure connection with every site.

Secure connections are supported by an intricate dance that enables the server you’re corresponding with to demonstrate that it is registered with a trusted third party known as a certificate authority (CA). Your browser will check to ensure it’s a valid certificate, and then negotiate an encrypted connection between your browser and the server. When there’s a problem with one of the steps in this dance, your browser will give you some visual indication that the connection may be compromised (as shown in Figure 21.25).

•Figure 21.25 Certificate error in Safari

Pop-up and Ad Blockers

Since the earliest days of the Web, users and browsers have been in a back-and-forth war with scammers and advertisers. Two of the main tools at our disposal are the ability to block pop-ups (new windows that open when you visit a site, generally with ads in them) and advertisements. The ability to block these is built directly into some browsers, but pop-up and ad blockers are also some of the most frequently used browser extensions. Figure 21.26 shows my favorite ad-blocking extension hard at work!

•Figure 21.26 uBlock Origin obliterating ads in Firefox!

Browsing Data

Because we use browsers to do weird things like collect rare Beanie Babies, spend so much time bingeing old soap operas that Netflix has to ask if we’re okay, and ask a search engine about this strange spot on the back of our hands, a lot of people are concerned about the privacy and security implications of the data trail that browsers create.

The CompTIA A+ 1102 exam objectives touch on four different ways to work with browsing data, but before we consider those I want to zoom out and just think about the main kinds of data our browsers accumulate:

■ A running list (called the history) of each page we visit (and potentially which pages are currently open or were open the last time you closed the browser)

■ Scripts running on sites we visit (i.e., cookies and local storage)

■ Site-specific settings and passwords we configure

■ Form data (such as our postal address) that we enable the browser to auto-fill

■ Cached copies of recently downloaded resources

■ A list of recently downloaded files

Each browser handles this data a little differently, and the bad news is that if you don’t clean out this stored data, your browser runs slower because every webpage you’ve visited has to re-download—again. The good news is that there is a way to clear the data and apply settings to control how often you would like for your cache to be cleared. This is called clearing cache. When you go to clear browsing data in Chrome, you’ll have the option to select specific types of data and how much of it to delete. The closest equivalent in Apple Safari enables you to remove data for specific sites—but you’ll have to clear things like the history or download list separately. Figure 21.27 shows the options for clearing browsing data in Chrome and Safari.

•Figure 21.27 Clearing browsing data in Google Chrome (left) and Apple Safari (right)

Privacy concerns aren’t the only reason to clear your browser’s cache and/or site data. From time to time, your browser or the site you’re visiting will make a mistake and you’ll end up with some incomplete, incorrect, or simply outdated data in your browser. Clearing the cache, cookies, local storage, and any other browser data for a site can be an important troubleshooting step whenever a Web site or an application you access through your browser is misbehaving.

All of the big browsers also support some kind of private-browsing mode that will disable some forms of data collection and discard most other types of data as soon as you close the private window. These browser modes aren’t perfect—some sites will still be tracking you on their end—but it can be a quick way to avoid leaving a bunch of your data behind when you use a shared computer.

Some browsers also support something like the opposite of this—the ability to sign in (either to the browser itself, or your OS provider’s cloud account) and have your browser data synchronized among multiple devices. If you use your browser’s built-in password manager, it can be particularly useful to have browser data in sync across all the devices you use. You probably shouldn’t, however, sign in and set up synchronization on a shared device.

Configuring Web Browsers

Most of the big Web browsers have a built-in settings menu that you’ll find inside the main application menu, which usually has a button in the top-right corner. In Google Chrome and Microsoft Edge, you can click the three-dot icon in the upper-right corner of the browser and select Settings. In Mozilla Firefox, the icon is in the same place but looks like a stack of horizontal lines—click it and select Options. (Safari is the outlier, here. In it, you open the Safari menu on the menu bar and select Preferences.)

These menus are very similar but differ from browser to browser (and they change over time). Figure 21.28 shows what the Settings menu in Google Chrome looks like. Take some time to download all the big browsers that you have access to, use each one a bit, and explore their settings. Knowledge of one browser will help you set up the others.

•Figure 21.28 Google Chrome Settings

Internet Options

Back in the 1990s, Microsoft made a mistake that we’re all still paying for: it deeply integrated its Web browser at the time, Internet Explorer (IE), with Windows. Instead of configuring IE directly in the application, Microsoft gave this job to a Control Panel applet named Internet Options. Nearly 30 years later, Internet Options (see Figure 21.29) contains a grab-bag of settings that affect Internet Explorer, Microsoft Edge, and potentially any other program that uses the Internet.

•Figure 21.29 Internet Options applet

The sun is slowly setting on Internet Explorer. It hasn’t been the default Windows browser since 2015, and as of June 2022 it’s no longer supported in the most common version of Windows 10. The CompTIA A+ 1102 exam objectives for Windows 11 appear to be leaving Internet Options behind—but the objectives for Windows 10 still expect you to recognize scenarios that make use of the old Internet Options applet. It’s hard to know exactly what CompTIA has in mind, so I’ll give you a quick outline of the options.

The Internet Options applet has seven tabs:

■ The General tab has settings to control the most basic features of Internet Explorer: the home page, tab management, your browsing history, searching, and other appearance controls. It’s where you’d delete or change how Internet Explorer stores the Web sites you’ve visited.

■ The Security tab enables you to adjust security settings for a particular zone, such as the Internet, your local intranet, trusted sites, and restricted sites. You can configure which Web sites fall into which zones. This is where you’d relax security rules for an intranet site.

■ The Privacy tab works a lot like the Security tab, except it controls privacy matters (like cookies, location tracking, pop-ups, and whether browser extensions run in private browsing mode). There is a slider that enables you to control what is blocked—everything is blocked on the highest setting; nothing is blocked on the lowest.

■ The Content tab controls what your browser will and will not display. This is where you’d gate access to insecure or objectionable sites and tweak the AutoComplete feature that pre-fills some forms.

■ The Connections tab enables you to set up a connection to the Internet via broadband or dial-up; connect to a VPN; or adjust some LAN settings, which you probably won’t need to deal with except perhaps to configure a proxy server connection.

■ Finally, there are the Programs and Advanced tabs. These two are not used much today, but here you can find settings to control add-ons for Internet Explorer, what editor to use for editing HTML, and a list of settings to control how IE works at a granular level. In addition, many of these controls you will find here have been moved to the Settings app or other applets, and the buttons in Internet Options are just links to that setting’s new location.

Communicating with Others

If you’re like me, one of the most important things you do on the Internet these days is communicate with your friends, family, and coworkers. It wasn’t all that long ago, really, that you either talked in person, talked on the phone, or wrote a letter, but now there are dozens of ways to keep in touch with people you know—and even strangers! The CompTIA A+ 1102 exams only focus on the two of the oldest and most business-oriented: e-mail and VoIP.

To set up and access e-mail, you have a lot of choices today. You can use the traditional ISP method that requires a dedicated e-mail application. Today, though, people use e-mail clients built into whatever device they use. Finally, you can use a Web-based e-mail client accessible from any device. The difficulty with this section is that all of this is blending somewhat with the advent of account-based access to devices, such as using your Microsoft account to log on to your Windows PC.

All e-mail addresses come in the accountname@Internet domain format. To add a new account, provide your name, e-mail address, and password. Assuming the corporate or organization server is set up correctly, that’s all you have to do today.

In the not so distant past, however, and still referenced on the CompTIA A+ exams, setting up an e-mail client had challenges. Not only did you have to have a valid e-mail address acquired from the provider and a password, you had to configure both the incoming and outgoing mail server information. You would add the names of the Post Office Protocol version 3 (POP3) or Internet Message Access Protocol version 4 (IMAP4) server and the Simple Mail Transfer Protocol (SMTP) server. The POP3 or IMAP server is the computer that handles incoming (to you) e-mail. Most mail happens through the latest version of IMAP, IMAP4. The SMTP server handles your outgoing e-mail.

Integrated Solutions All mobile devices have an integrated e-mail client, fully configured to work within the mobile ecosystem. Apple devices, such as the iPad, enable you to create and use an iCloud account that syncs across all your Apple devices. The iCloud e-mail setup process assumes you’ll use iCloud for all that sending and receiving stuff and thus you have no other configuration to do. All the settings for IMAP, POP, SMTP, and so on happen behind the scenes. CompTIA calls this sort of lack of configuration integrated commercial provider e-mail configuration. That’s pretty accurate, if a little bland. You will see more of this in Chapter 24.

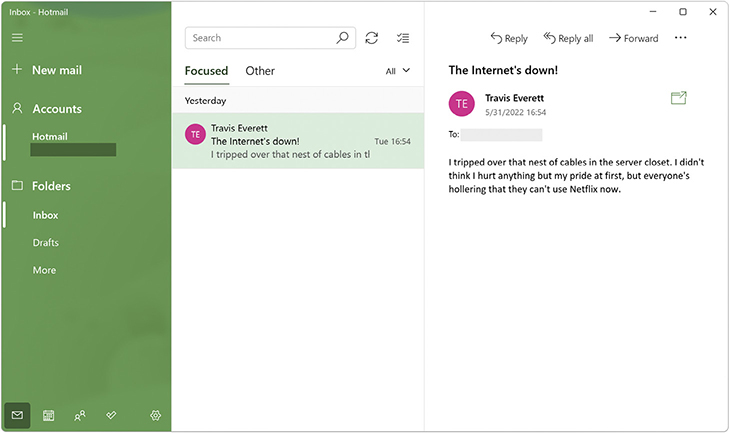

Web Mail Most people use Web-based e-mail, such as Yahoo! Mail, Gmail from Google, or Exchange Online from Microsoft, to handle all of their e-mail needs (see Figure 21.30). Web-based mail offers the convenience of having access to your e-mail from any Internet-connected computer, smartphone, tablet, or other Internet-connected device. While desktop clients may offer more control over your messages and their content, Web-based e-mail has caught up in most respects. For example, Web services can provide a superior spam-filtering experience by relying on feedback from a large user base to detect unwanted or dangerous messages.

•Figure 21.30 Web-based e-mail

Unified Internet Accounts When I log on to my Windows desktop computer, I use my Microsoft account, a fully functional e-mail account hosted by Outlook. Doing so defines the default e-mail experience on that machine. When I access the Mail client, for example, it immediately accesses my Hotmail account (see Figure 21.31). There’s no configuration from a user’s or tech’s perspective. The same is true when you log on to any Apple device, whether it’s a mobile device or smartphone, or a macOS desktop machine. Microsoft calls this feature Live sign in.

•Figure 21.31 Windows Mail

Organization E-mail For decades now, businesspeople around the world have used Microsoft Outlook—part of the Microsoft Office suite—to manage their e-mail. In the Office 365 era, just logging in to your Microsoft account will automatically configure Outlook to use the correct Exchange server. If your organization runs its own Exchange server, you may need to set it up manually. The main times you’ll need to intervene are when there isn’t a domain network to lean on, when something’s changing (like when a company rebrands itself), or when the existing Outlook profile gets broken (see Figure 21.32).

•Figure 21.32 Mail applet in Windows 10

Voice over IP

You can use Voice over IP (VoIP) to make voice calls over your computer network. Why have two sets of wires, one for voice and one for data, going to every desk? Why not just use the extra capacity on the data network for your phone calls? That’s exactly what VoIP does for you. VoIP works with every type of high-speed Internet connection, from DSL to cable to satellite.

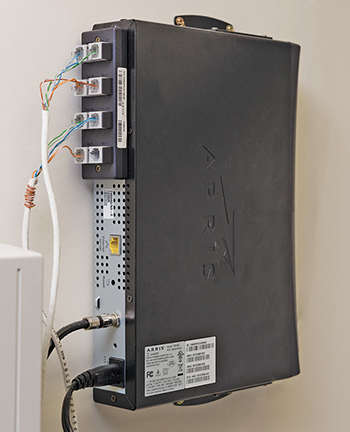

VoIP doesn’t refer to a single protocol but rather to a collection of protocols that make phone calls over the data network possible. The most common VoIP application protocol is Session Initiation Protocol (SIP), but some popular VoIP applications such as Skype are completely proprietary.

Vendors such as Skype, Cisco, Vonage, Arris, and Comcast offer popular VoIP solutions, and many corporations use VoIP for their internal phone networks. VoIP isn’t confined to your computer, either. It can completely replace old copper phone lines. Two popular ways to set up a VoIP system are to either use dedicated VoIP phones, like the ones that Cisco makes, or use a dedicated VoIP box (see Figure 21.33) that can interface with your existing analog phones.

•Figure 21.33 Arris VoIP telephony modem

True VoIP phones have RJ-45 connections that plug directly into the network and offer advanced features such as HD-quality audio and video calling. Unfortunately, these phones require a complex and expensive network to function, which puts them out of reach of most home users.

For home users, it’s much more common to use a VoIP phone adapter to connect your old-school analog phones. These little boxes are very simple to set up: just connect it to your network, plug in a phone, and then check for a dial tone. With the VoIP service provided by cable companies, the adapter is often built right into the cable modem itself, making setup a breeze.

Remote Access

One of the big advantages of a ginormous, always-on network of networks is that many people can do some or all of their work remotely—whether that means from another city, or just without walking from workstation to workstation. You can take advantage of remote access technologies to manage servers and workstations and use them to train users or troubleshoot their problems. Likewise, you’ll almost certainly need to configure some resource to ensure it’s available remotely.

The CompTIA A+ 1102 exam objectives want you to know about quite a few remote access technologies, so let’s dive in!

Telnet and SSH

Telnet is a terminal emulation program for TCP/IP networks that uses port 23 and enables you to connect to a server or fancy router and run commands on that machine as if you were sitting in front of it. This way, you can remotely administer a server and communicate with other servers on your network. Unfortunately, Telnet shares FTP’s bad habit of sending passwords and usernames as clear text, so you should generally use it only as a last resort, and only within your own LAN.

The secure, modern alternative to Telnet, Secure Shell (SSH), has replaced Telnet almost everywhere Telnet used to be popular. As a user, SSH works just like Telnet. Behind the scenes, SSH uses port 22, and the entire connection is encrypted to prevent eavesdroppers from reading your data. SSH has another trick up its sleeve: it can move files or any type of TCP/IP network traffic through its secure connection. This practice, called tunneling, plays a role in other secure networking technologies that we’ll discuss later in the chapter such as SFTP and VPN.

SSH is encrypted, but its security is only as strong as your password. If you have a machine with a publicly accessible SSH server, it will be under constant attack by hackers trying to guess the password!

Remote Desktop

The kind of remote command-line access you can get with SSH is great for a lot of geeky administrative tasks, but it isn’t so good at general productivity—like accessing an application that is only installed on one machine. When you need remote access to the full graphical desktop, you need a remote desktop application.

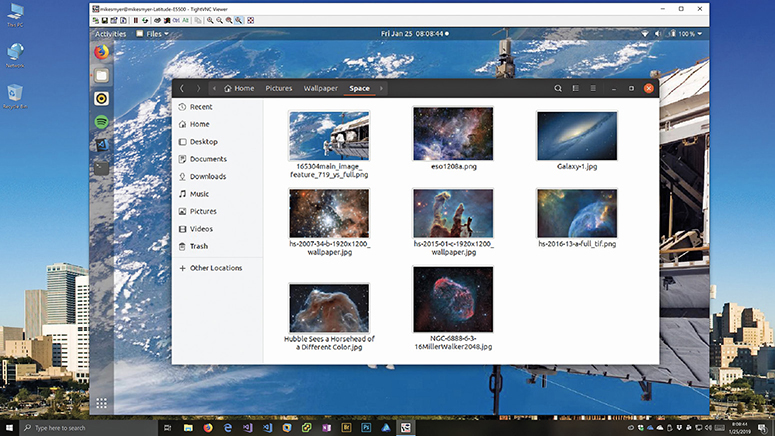

While some operating systems include a remote desktop client, many third-party remote desktop applications are also available. Most of these make use of either the Remote Desktop Protocol (RDP) or Virtual Network Computing (VNC). TightVNC, for example, is totally cross-platform, enabling you to run and control a Windows system remotely from your Mac or vice versa, for example. Figure 21.34 shows TightVNC in action. The Screen Sharing app built into macOS also uses VNC; it’s modest, but it’s good enough for basic remote access, collaboration, and light remote troubleshooting.

•Figure 21.34 TightVNC in action

Windows offers an alternative to VNC: Remote Desktop Connection. Remote Desktop Connection provides control over a remote server with a fully graphical interface. Your desktop becomes the server desktop (see Figure 21.35).

•Figure 21.35 Windows Remote Desktop Connection dialog box

Wouldn’t it be cool if, when a client called about a technical support issue and says that something doesn’t work, you could transfer yourself from your desk to your client’s desk to see precisely what the client sees? This would dramatically cut down on the miscommunication that can make a tech’s life so tedious. Microsoft Remote Assistance (MSRA) does just that (though there are also other third-party applications that offer the same capability). Remote Assistance enables you to give anyone control of your desktop or take control of anyone else’s desktop. If a user has a problem, that user can request support (see Figure 21.36) directly from you. Upon receiving the support-request e-mail, you can then log on to the user’s system and, with permission, take the driver’s seat.

•Figure 21.36 Remote Assistance wizard

With Remote Assistance, you can do anything you would do from the actual computer. You can troubleshoot some hardware configuration or driver problem. You can install drivers, roll back drivers, download new ones, and so forth. You’re in command of the remote machine as long as the client allows you to be. The client sees everything you do, by the way, and can stop you cold if you get out of line or do something that makes the client nervous! Remote Assistance can help you teach someone how to use a particular application. You can log on to a user’s computer and fire up Outlook, for example, and then walk through the steps to configure it while the user watches. The user can then take over the machine and walk through the steps while you watch, chatting with one another the whole time. Sweet!

Remote desktop applications provide everything you need to access one system from another. They are common, especially considering that Microsoft provides Remote Desktop for free. Whichever application you use, remember that you will always need both a server and a client program. The server goes on the system you want to access, and the client goes on the system you use to access the server. With many solutions, the server and client software are integrated into a single product.

In Windows, you can turn Remote Assistance and Remote Desktop on and off and configure other settings. Go to the System applet in Control Panel and then select the Remote settings link on the left. Under the Remote tab in System Properties you will see checkboxes for both Remote Assistance and Remote Desktop, along with buttons to configure more detailed settings.

Video-Conferencing Software

The first few things I think of when it comes to video-conferencing software are a screen with a grid of little faces and an occasional cat wandering around, the dull background roar from that guy who called in from his car on the highway, and people trying to talk over each other. But there are some interesting surprises lurking in the presentation-focused features of programs like Microsoft Teams and Zoom.

These programs not only make it easy for someone to share windows or even their entire desktop with whoever else is on the call—but they enable you to give someone else on the call control of your desktop. As a tech, you can use this feature to help a user troubleshoot a problem just like you would in Remote Assistance.

Virtual Private Networks

It’s been possible to connect to a remote network for a long time, but back before the Internet existed the main connection options were a telephone line or an outrageously expensive private connection. The introduction of the Internet gave people a way to stop using dial-up and expensive private connections and use the Internet instead, but they wanted to do it securely.

A popular way to secure connections like this entails setting up an encrypted tunnel between the two points—over the open Internet (see Figure 21.37)—creating what we call a virtual private network (VPN).

•Figure 21.37 VPN connecting computers across the United States

An encrypted tunnel requires endpoints—the ends of the tunnel where the data is encrypted and decrypted. In the SSH tunnel you’ve seen thus far, the client for the application sits on one end and the server sits on the other. VPNs do the same thing. Either some software running on a computer or, in some cases, a dedicated Internet appliance such as an endpoint management server must act as an endpoint for a VPN (see Figure 21.38).

•Figure 21.38 Typical tunnel

VPNs require a protocol that itself uses one of the many tunneling protocols available and adds the capability to ask for an IP address from a local DHCP server to give the tunnel an IP address that matches the subnet of the local LAN. The connection keeps the IP address to connect to the Internet, but the tunnel endpoints act like NICs (see Figure 21.39). Let’s look at how to set up a VPN connection.

•Figure 21.39 Endpoints must have their own IP addresses.

In Windows, type VPN in Start | Search and select VPN settings. Clicking Add a VPN connection presents you with a screen where you can enter all your VPN server information (see Figure 21.40). Your network administrator will most likely provide this information to you. The result is a virtual network card that, like any other NIC, gets an IP address from the DHCP server back at the office.

•Figure 21.40 Adding a VPN connection in Windows

When your computer connects to the VPN server on the private network, it creates a secure tunnel through the Internet back to the private LAN. Your client takes on an IP address for that network, as if your computer were plugged into the LAN back at the office.

Depending on the configuration of your VPN connection, your Internet traffic may go through your office first. This can help secure the rest of your Internet traffic—but it can also slow it down (and large downloads can bottleneck the organization network if it doesn’t have enough bandwidth). VPN connections are convenient, but they can give an attacker an easy way to get into your network—especially if they steal a user’s credentials or a user device configured to automatically log in.

File Transfer Software

Sometimes users don’t even need direct access to an organization’s network or workstations to get their work done remotely—they just need access to the right files! There’s a whole ecosystem of services that enable you to share, synchronize, and transfer files among different users or among a single user’s devices. Some of the best-known examples are Dropbox, Apple iCloud, Google Drive, and Microsoft OneDrive—but there are plenty more. In general, software like this comes with an application that you’ll install on every device you want to synchronize files across, and then use the application to specify exactly what gets synchronized.

These services can be an obvious alternative to opening up your entire network to attack if someone’s credentials are swiped—but they also make it a lot easier for users to intentionally or accidentally leak files with sensitive information. Each organization will have to make its own call on these trade-offs.

Desktop Management Software

The remote access technologies you’ve seen so far are fairly limited. They give you a specific kind of access, but otherwise leave the rest up to you. Desktop management software, however, gives you a full suite of management tools you can use to configure devices, update or install software, open a remote desktop session to interactively fix issues, enforce security policies, manage user accounts, turn off idle systems—and much more. You may also hear people call this software endpoint management software (especially when the software also manages mobile devices).

Remote Monitoring and Management (RMM)

Remote monitoring and management (RMM) software builds on the capabilities of desktop or endpoint management software by also layering in robust monitoring and management of your network—including network devices and servers. Organizations that use an RMM solution have one place to go to understand and manage the health of their wired and wireless network infrastructure, ensure the servers running in their network have the latest security updates, and monitor workstations for unauthorized software!

Sharing and Transferring Files

Once upon a time, someone had to physically move their body to share files with someone else or move files between systems. You’d put them on some kind of disk, and then walk the disk over (or throw it like a frisbee) to whoever needed it. At the dawn of the computing era, it was even common for people to “install” software by hand-typing from a paper copy of the program’s source code!

All of this extra work is a big part of why early networks were really exciting even long before they were connected to the Internet. Sharing and transferring files is every bit as important in the Internet era—so much so that the way we transfer files has been reinvented a few times over. Let’s look at a few of the most common ways it’s been done.

File Transfer Protocol

File Transfer Protocol (FTP) emerged in the early 1970s (though it’s been updated several times since then) as a great way to transfer files between client systems and an FTP server. It was also the way to download software or update your Web site on the early Internet. FTP server software exists for most operating systems, so you can use FTP to transfer data between any two systems regardless of the OS. FTP uses ports 20 and 21.

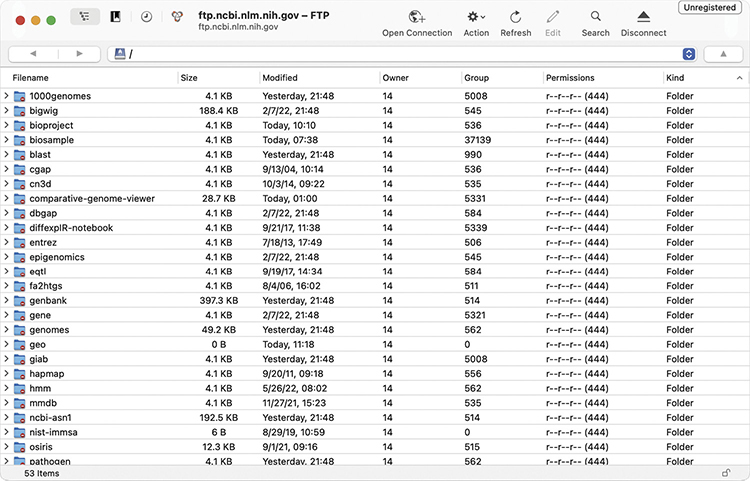

To access an FTP site, you must use an FTP client such as FileZilla or Cyberduck (shown in Figure 21.41). For much of the Internet’s life, it was possible to access FTP servers through a Web browser—but the sun set on this era in 2021, when both Mozilla Firefox and Google Chrome removed support.

•Figure 21.41 The Cyberduck FTP program running on macOS

FTP servers require you to log on, though many public download-only servers (and clients) will use “anonymous” as the default. Most FTP clients can store username and password settings to make it easy to reconnect to servers you use regularly. Beware that FTP was developed during a more trusting time—your username and password will be sent over the network in easily intercepted clear text. Don’t use the same password for an FTP server that you use for your domain logon at the office!

TFTP

Trivial FTP (TFTP) is an old, bare-bones file transfer protocol that lacks many of the features—like authentication and listing files—that FTP includes. It isn’t very popular, but its simplicity gives it a leg up in some narrow cases such as downloading system images to boot a device from the network. If you recall that a big difference between UDP and TCP is that TCP can detect and recover from errors, you might be surprised to know TFTP uses UDP port 69. File transfer does need to avoid errors, and TFTP has its own built-in mechanisms for doing so.

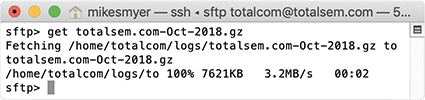

SFTP

Secure FTP is a network protocol for transferring files over an encrypted SSH connection. You can (and should!) use SFTP for the same things you’d use FTP for—but it is technically its own distinct protocol. The SFTP protocol was written as an extension of SSH, so you can find SFTP client and server support built into SSH software, such as the popular OpenSSH. In Figure 21.42, I’m using SFTP to transfer a Web server log.

•Figure 21.42 OpenSSH

1101

Embedded Systems

One easy-to-miss aspect of the computing landscape is that there are tons and tons of computers out there that don’t look like computers. These computers, known as embedded systems, have been built into all kinds of stuff—things like appliances, game consoles, cars, medical equipment, missiles, equipment in factories—for decades now.

For a long time, these computers were modest. They played small roles in controlling a device or supporting specific features. Over time, many of these computers have evolved into networked smart devices that are both more capable and cause new problems. Let’s consider what these devices look like in an industrial setting first, and then see how they manifest in day-to-day life.

Industrial Control Systems

Once upon a time, factories were just a place where a bunch of people came together and used human-powered tools to build things. Waves of new technologies slowly transformed them. For much of the 19th and 20th centuries, factories were places where humans directly controlled or worked in tandem with powerful machines driven by steam or electricity. In the 21st century, our most-advanced factories are becoming fully automated, palace-sized machines maintained by a small number of people.

This latest transformation is being driven by increasingly sophisticated industrial control systems (ICSs) that monitor and control (or, at least, help humans monitor and control) many, if not all, parts of the equipment, materials, and processes they oversee.

Some key industrial technologies (like railroads, power grids, networks of water pumps, pipelines, and so on) that tend to be distributed over wide areas often use a specialized type of ICS. Supervisory control and data acquisition (SCADA) systems are designed to manage processes that are spread out over a wide area—and to help with the problem of operating the system safely when something temporarily disrupts connectivity between parts of the system.

Organizations that operate these control systems must carefully balance two needs that can come into conflict. Since these systems might be monitoring and controlling dangerous high-energy processes such as a hydroelectric dam, nuclear power plant, or a process for melting and pouring molten metal, keeping them secure can be a matter of life and death. The other side of this coin is that remote access can make it much easier to manage these systems efficiently and safely.

The Internet of Things

Some embedded systems go a step beyond just being able to use the Internet for remote monitoring and management. These devices, which actively use the Internet all on their own during their regular operation, are said to be part of the Internet of Things (IoT). Some of the IoT devices you’re most likely to encounter in day-to-day life include things like refrigerators, thermostats, light switches, security cameras, door locks, and smart speakers/digital assistants—but the IoT also includes less-obvious things like parking meters, vending machines, and environment sensors.

We can access, configure, and command these devices over the Internet, but more importantly, the devices themselves regularly use the Internet to report conditions, initiate credit card transactions, download software updates, and so on. I can’t show you how every device works, but let’s take a look at one of the most iconic: the Nest smart thermostat (see Figure 21.43).

•Figure 21.43 Wi-Fi details on a Nest thermostat (left) and Nest smartphone app (right)

You can control a smart thermostat from any device connected to the Internet, such as your computer at the office or your smartphone on the commute. But the Nest thermostat can also use the Internet all on its own—for example, to report when it ran the heater or air conditioner or to automatically adjust its usage to the real-time price of electricity in your area.

■ Internet Troubleshooting

There isn’t a person who’s spent more than a few hours on a computer connected to the Internet who hasn’t run into some form of connectivity problem. I love it when I get a call from someone saying, “The Internet is down!” as I always respond the same way: “No, the Internet is fine. It’s the way you’re trying to get to it that’s down.” Okay, so I don’t make a lot of friends with that remark, but it’s actually a really good reminder of why we run into problems on the Internet. Let’s review the common symptoms CompTIA lists on their objectives for the CompTIA A+ 220-1101 exam and see what we can do to fix these all-too-common problems.

The dominant Internet setup for a SOHO environment consists of some box from your ISP such as a cable/DSL modem, fiber ONT, etc., that connects via Ethernet cable to a home router. This router is usually 802.11 capable and includes four Ethernet ports. Some computers in the network connect through a wire and some connect wirelessly (see Figure 21.44). It’s a pretty safe assumption that CompTIA has a setup like this in mind when talking about Internet troubleshooting, and we’ll refer to this setup here as well.

•Figure 21.44 Typical SOHO setup

One quick note before we dive in: Most Internet connection problems are network connection problems. In other words, everything you learned in Chapter 19 applies here. We’re not going to rehash those repair problems in this chapter. The following issues are Internet-only problems, so don’t let a bad cable fool you into thinking a bigger problem is taking place.

No Connectivity

As you’ll remember from Chapter 19, “no connectivity” has two meanings: a disconnected NIC or an inability to connect to a resource. Since Chapter 19 already covers wired connectivity issues and Chapter 20 covers wireless issues, let’s look at lack of connectivity from a “you’re on the Internet but you can’t get to a Web site” point of view:

1. Can you get to other Web sites? If not, go back and triple-check your local connectivity.

2. Can you ping the site? Go to a command prompt and try pinging the URL as follows:

The ping is a failure, but we learn a lot from it. The ping shows that your computer can’t get an IP address for that Web site. This points to a DNS failure, a very common problem. To fix a failure to access a DNS server, try these options:

■ In Windows, go to a command prompt and type ipconfig /flushdns:

■ In Windows 10, go to Network & Internet in the Settings app and click Network troubleshooter (see Figure 21.45). (This option still exists in Windows 11, but you may have to use Find a setting to search for it.)

•Figure 21.45 Diagnosing a network problem in Windows 10

■ Try using another DNS server. There are lots of DNS servers out there that are open to the public. Try Google’s famous 8.8.8.8 and 8.8.4.4 or Cloudflare’s 1.1.1.1 and 1.0.0.1.

If DNS is OK, make sure you’re using the right URL. This is especially true when you’re entering DNS names into applications such as e-mail clients.

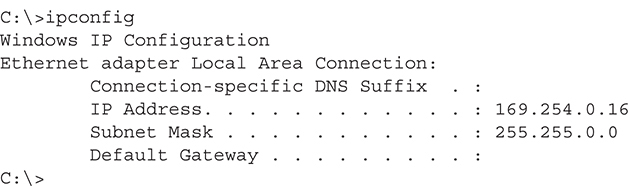

Limited Connectivity

Limited connectivity points to a DHCP problem, assuming you’re connected to a DHCP server. Run ipconfig and see if you have an APIPA address:

Uh-oh! No DHCP server! If your router is your DHCP server, try restarting the router. If you know the Network ID for your network and the IP address for your default gateway (something you should know—it’s your network!), try setting up your NIC statically.

Local Connectivity

Local connectivity means you can access network resources but not the Internet. First, this is a classic symptom of a downed DHCP server since all the systems in the local network will have APIPA/link local addresses. However, you might also have a problem with your router. You need to ping the default gateway; if that’s successful, ping the other port (the WAN port) on your router. The only way to determine the IP address of the other port on your router is to access the router’s configuration Web page and find it (see Figure 21.46). Every router is different—good luck!

•Figure 21.46 Router’s WAN IP address

You can learn a lot by looking at your WAN IP address. Take a look at Figure 21.47. At first glance, it looks the same as Figure 21.46, but notice that there is no IP address. Most ISPs don’t provide static IP addresses—they simply give you the physical connection, and your router’s WAN network card uses DHCP, just like most internal networks. If you’re lucky, you can renew your DHCP address using some button on the router’s configuration. If not, try resetting the cable/fiber/DSL modem. If that doesn’t work, it’s time to call your ISP.

•Figure 21.47 No WAN connection

Slow Network Speeds

No matter how fast the connection is, we all want our Internet to go faster. People tolerate a certain amount of waiting for a large program to download or an HD video to buffer, but your connection can sometimes slow down to unacceptable speeds.

Remember that your Internet connection has a maximum speed at which it can transfer. If you divide that connection between multiple programs trying to use the Internet, all of your programs will connect very slowly. To see what’s happening on your network, open a command prompt and type netstat, which shows all the connections between your computer and any other computer. Here’s a very simplified example of netstat output:

If you look at the Foreign Address column, you’ll see that most of the connections are Web pages (HTTP and HTTPS) or shared folders (microsoft-ds, netbios-ssn), but what is the connection to 12.162.15.1:57080? Not knowing every connection by heart, I looked it up on Google and found out that there was a background torrent program running on my machine. I found the program and shut it down.

When everyone on the network is getting slow Internet connectivity, it’s time to check out the router. In all probability, you have too many people who need too much bandwidth—go buy more bandwidth!

When additional bandwidth isn’t an acceptable solution, you’ll need to make the most of what you have. Your router can use a feature called Quality of Service (QoS) to prioritize access to network resources. QoS enables you to ensure certain users, applications, or services are prioritized when there isn’t enough bandwidth to go around by limiting the bandwidth for certain types of data based on application protocol, the IP address of a computer, and all sorts of other features. Figure 21.48 is a typical router’s QoS page.

•Figure 21.48 QoS

Latency and Jitter

Any real-time application—things like VoIP, teleconferencing, streaming video, and video games—can prove unworkable if you have miserable high latency. In all of these cases, but especially with VoIP, a key to troubleshooting is that low network latency is more important than high network speed (as long as your connection meets the minimum bandwidth that the application needs). The higher the latency, the more problems, such as noticeable delays during your VoIP call.

Another kind of latency problem, jitter, is caused by rapid latency fluctuations, which can in turn make packets arrive in bursts or out of order. While true high latency generally just causes long delays, jitter can garble audio and video signals or break the connection altogether. In all cases, you can assess the latency (and how consistent it is) with tools such as ping, tracert/traceroute, and pathping.

Try This!

Try This!

Checking Latency with ping

Latency is the bane of any VoIP call because of all the problems it causes if it is too high. A quick way to check your current latency is to use the ever-handy ping, so try this!

1. Run ping on some known source, such as www.microsoft.com or www.totalsem.com.

2. When the ping finishes, take note of the average round-trip time at the bottom of the screen. This is your current latency to that site.

Poor VoIP Call Quality

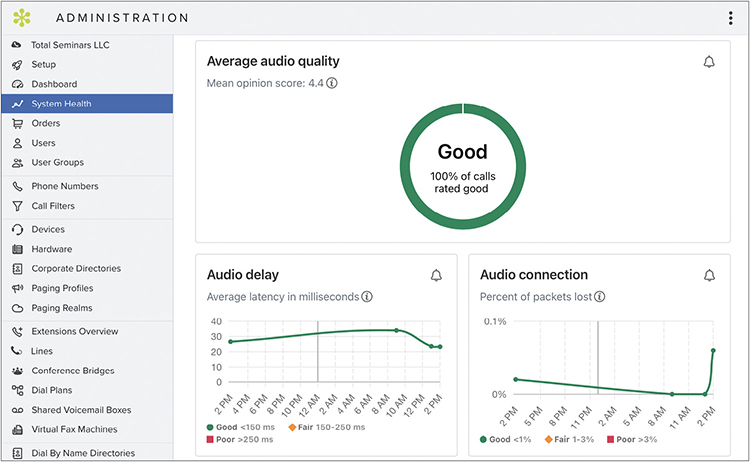

When the main symptom users are reporting is poor VoIP quality, you may need to draw on your knowledge of multiple problems to find a fix. Many VoIP providers have a dashboard where you can log in and see call statistics. The dashboard may not answer your exact question, but most dashboards usually have some kind of call-quality metric (as shown in Figure 21.49) that you can quickly check for signs of obvious trouble.

•Figure 21.49 Call quality metric in GoTo Administration Panel

Here are a few things to keep in mind if you need to dig deeper:

■ Most VoIP problems could be on the other end of the call. Before you jump into diagnosing your own network, see if calls to other locations and networks have the same problem.

■ If your organization uses standalone VoIP phones, it’s a good idea to see if swapping the phone out for another fixes the issue.

■ If the conversation has long delays that are making it hard to communicate, check for high latency.

■ If the audio is choppy or distorted, check for jitter. (Some VoIP providers track this for you.)

■ If the audio quality is really low, look into whether the network is congested or just doesn’t have enough bandwidth.

■ Networks often need to use QoS to avoid VoIP call quality issues—especially when the network is busy—so each of these call-quality problems might indicate that QoS isn’t enabled or working correctly. Ensure your router supports QoS and that it’s enabled on your router and/or VoIP router. If it’s enabled, you may need to tune the settings to prioritize VoIP traffic.

Chapter 21 Review

■ Chapter Summary

After reading this chapter and completing the exercises, you should understand the following about the Internet.

Explain how the Internet works