The simple control panels you’ve read about so far in this chapter are designed for simplicity and convenience, but not for power. Windows XP Pro offers a second way to create, edit, and delete accounts: an alternative window that, depending on your taste for technical sophistication, is either intimidating and technical—or liberating and flexible.

It’s called the Local Users and Groups console.

You can open up the Local Users and Groups window in any of several ways:

Figure 17-8. Local Users and Groups is a Microsoft Management Console (MMC) snap-in. MMC is a shell program that lets you run most of Windows XP’s system administration applications. An MMC snap-in typically has two panes. You select an item in the left (scope) pane to see information about it displayed in the right (detail) pane.

Choose Start→Control Panel→Administrative Tools→Computer Management. Click the Local Users and Groups icon in the left pane of the window.

Choose Start→Run, type Lusrmgr.msc, and click OK.

Domain PCs only: Choose Start→Control Panel. Open User Accounts, click the Advanced tab , and then, under Advanced User Management, click the Advanced button.

In any case, the Local Users and Groups console appears, as shown in Figure 17-8.

In this console, you have complete control over the local accounts (and groups, as described in a moment) on your computer. This is the real, raw, unshielded command center, intended for power users who aren’t easily frightened.

The truth is, you probably won’t use these controls much on a domain computer. After all, most people’s accounts live on the domain computer, not the local machine. You might occasionally have to log in using the local Administrator account to perform system maintenance and upgrade tasks, but you’ll rarely have to create new accounts.

Workgroup computers are another story. Remember that you’ll have to create a new account for each person who might want to use this computer—or even to access its files from across the network. If you use the Local Users and Groups console to create and edit these accounts, you have much more control over the new account holder’s freedom than you do with the User Accounts control panel.

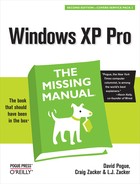

Figure 17-9. When you first create a new user, the “User must change password at next logon” checkbox is turned on. It’s telling you that no matter what password you make up when creating the account, your colleague will be asked to make up a new one the first time he logs in. This way, you can assign a simple password (or no password at all) to all new accounts, but your underlings will still feel free to devise passwords of their own choosing, and the accounts won’t go unprotected

To create a new account in the Local Users and Groups console, start by clicking the Users folder in the left side of the console (technically called the scope pane). On the right side of the console (the detail pane), you see a list of the accounts already on the machine. It probably includes not only the accounts you created during the Windows XP installation (and thereafter), but also the Administrator and Guest accounts described earlier in this chapter

To create a new account, choose Action→New User from the Action menu. In the New User dialog box (Figure 17-9), type a name for the account (the name this person will type or choose when logging in), the person’s full name, and if you like, a description. (Microsoft no doubt has in mind “Shipping manager” rather than “Short and balding,” but the description can be anything you like.)

In the Password and Confirm Password text boxes, specify the password that your new colleague will need to access the account. Its complexity and length are up to you and your innate sense of security paranoia.

Tip

If you can’t create a new account, it’s probably because you don’t have the proper privileges yourself. You must have an Administrator account (Section 16.8) or belong to the Power Users or Administrators group (Section 17.5.3.1).

If you turn off the “User must change password at next logon” checkbox, you can turn on options like these:

User cannot change password. This person won’t be allowed to change the password that you’ve just made up. (Some system administrators like to maintain sole control over the account passwords on their computers.)

Password never expires. Using software rules called local security policies, an administrator can make account passwords expire after a specific time, periodically forcing employees to make up new ones. It’s a security measure designed to foil intruders who somehow get a hold of the existing passwords. But if you turn on this option, the person whose account you’re now creating will be able to use the same password indefinitely, no matter what the local security policy says.

Account is disabled. When you turn on this box, this account holder won’t be able to log on. You might use this option when, for example, somebody goes on sabbatical—it’s not as drastic step as deleting the account, because you can always reactivate the account by turning the checkbox off. You can also use this option to set up certain accounts in advance, which you then activate when the time comes by turning this checkbox off again.

Note

When an account is disabled, a red circled X appears on its icon in the Local Users and Groups console. (You may have noticed that the Guest account appears this way when you first install Windows XP.)

When you click the Create button, you add the new account to the console, and you make the dialog box blank again, ready for you to create another new account, if necessary. When you’re finished creating accounts, click Close to return to the main console window.

As you may have guessed from its name, you can also use the Local Users and Groups window to create groups —named collections of account holders.

Suppose you work for a small company that uses a workgroup network. You want to be able to share various files on your computer with certain other people on the network. You’d like to be able to permit them to access some folders, but not others. Smooth network operator that you are, you solve this problem by assigning permissions to the appropriate files and folders (Section 17.9.1).

In Windows XP Pro, you can specify different access permissions to each file for each person. If you had to set up these access privileges manually for every file on your hard drive, for every account holder on the network, you’d go out of your mind—and never get any real work done.

That’s where groups come in. You can create one group—called Trusted Comrades, for example—and fill it with the names of every account holder who should be allowed to access your files. Thereafter, it’s a piece of cake to give everybody in that group access to a certain folder, in one swift step. You end up having to create only one permission assignment for each file, instead of one for each person for each file.

Figure 17-10. The New Group dialog box lets you specify the members of the group you are creating. A group can have any number of users as members, and a user can be a member of any number of groups.

Furthermore, if a new employee joins the company, you can simply add her to the group. Instantly, she has exactly the right access to the right files and folders, without your having to do any additional work.

To create a new group, click the Groups folder in the left side of the Local Users and Groups console (Section 17.4.1). Choose Action→New Group. The New Group dialog box appears, as shown in Figure 17-10. Into the appropriate boxes, type a name for the group, and a description if you like. Then click Add.

A Select Users or Groups dialog box appears (the same box shown in Figure 17-20). Here, you can specify who should be members of your new group. (You can always add more members to the group, or remove them later.)

Finally, click OK to close the dialog box, and then click Create to add the group to the list in the console. The box appears empty again, ready for you to create another group.

You may have noticed that even the first time you opened the Users and Groups window, a few group names appeared there already. That’s because Windows XP comes with a canned list of ready-made groups that Microsoft hopes will save you some time.

For example, when you use the User Accounts control panel program to set up a new account, Windows automatically places that person into the Limited or Computer Administrator group, depending on whether or not you made him an administrator (Section 13.2.3). In fact, that’s how Windows knows what powers and freedom this person is supposed to have.

Here are some of the built-in groups on a Windows XP Professional computer:

Administrators. Members of the Administrators group have complete control over every aspect of the computer. They can modify any setting, create or delete accounts and groups, install or remove any software, and modify or delete any file.

But as Spiderman’s uncle might say, with great power comes great responsibility. Administrator powers make it possible to screw up your operating system in thousands of major and minor ways, either on purpose or by accident. That’s why it’s a good idea to keep the number of Administrator accounts to a minimum—and even to avoid using one for everyday purposes yourself, as described in the Tip in Section 17.3.3

Power Users. Members of this group have fewer powers than Administrators, but still more than mere mortals in the Users group. If you’re in this group, you can set the computer’s clock, change its monitor settings, create new user accounts and shared folders, and install most kinds of software. You can even modify some of the critical system folders, including the Windows folder and Windows→ System32 folder—but only for the purpose of installing applications that deposit files into those folders.

Clueless Power Users members can still cause trouble, so you should reserve the status for people who know what they’re doing. On the other hand, Power Users aren’t allowed to delete, move, or change core operating system files, so the damage they can inflict is relatively limited. This is a good kind of account for you, the wise administrator, to use for everyday work.

Users. Limited account holders ( Section 17.3.6) are members of this group. They can access their own Start menu and desktop settings, their own My Documents folders, the Shared Documents folder, and whatever folders they create themselves—but they can’t change any computer-wide settings, Windows system files, or program files.

If you’re a member of this group, you can install new programs—but you’ll be the only one who can use them. That’s by design; any problems introduced by that program (viruses, for example) are limited to your files and not spread to the whole system.

If you’re the administrator, it’s a good idea to put most new account holders into this group.

Figure 17-11. In the Properties dialog box for a user account, you can change the full name or description, modify the password options, and add this person to, or remove this person from, a group. The Properties dialog box for a group is simpler still, containing only a list of the group’s members.

Guests. If you’re in this group, you have pretty much the same privileges as members of the Users group. You lose only a few nonessential perks, like the ability to read the computer’s system event log (a record of behind-the-scenes technical happenings).

In addition to these basic groups, there are also two special-purpose groups:

Backup Operators. People in this group can back up and restore any of the files on the computer, even if those files are technically off-limits to these account holders. Members of this group can also log onto the system and shut it down, although they can’t modify any security settings.

Replicator. If you’re in this group, you can replicate files across a domain, a technical bit of bookkeeping of absolutely no interest to anyone outside the thrilling world of network administration.

To edit an account or group, just double-click its name in the Local Users and Groups window. A Properties dialog box appears, as shown in Figure 17-11.

You can also change an account password by right-clicking the name and choosing Set Password from the shortcut menu. But see Section 17.3.4earlier in this chapter for some cautions about this process.

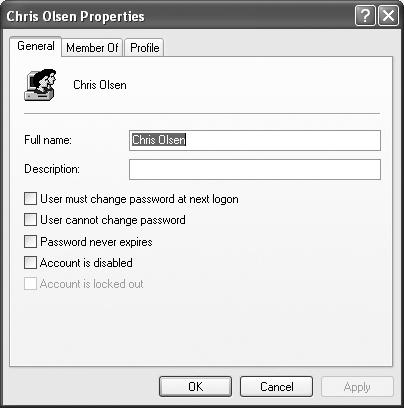

Figure 17-12. The first option here governs the appearance of the user-friendly Welcome screen shown in Figure 17-14. The second lets one person duck into his own account without forcing you to log off completely, as described in Section 17.3.3.. Note that these options are related—you can’t turn off the first without first turning off the second.