CHAPTER 3

An Overview of How Healthcare Is Paid For in the United States

Donald Nichols*

In this chapter, you will learn how to

• Explain how Americans pay for the healthcare they receive

• Describe how health insurance plays a central role in healthcare payment

• Understand what Medicare, Medicaid, and commercial health insurance programs are and how they are similar and how they are distinct

• Describe the five major types of insurance products

• Explain how healthcare reform is likely to affect the organization of and payment for healthcare in the future

Healthcare is different from most other goods and services purchased in the United States in that the purchase of healthcare services involves, in almost all cases, the participation of a third party: the health insurance firm. While there are mechanisms to provide (and to pay for) care to those who lack health insurance—so-called funds for charity or uncompensated care—the care for the vast majority of Americans is paid for by the government (through the Medicare and Medicaid programs) or by private health insurance, which is almost always tied to employment. To understand how healthcare is paid for in the United States, it is necessary first to understand how insurance operates in the United States.

The Nature of Health Insurance

In theory, the objective of health insurance is to pool risk. Illness—particularly catastrophic illness that could bankrupt a family—is (fortunately) rare. Insurance is a vehicle that allows individuals to pay (for example, annually) a relatively small amount to an insurance pool, which covers the costs (of necessary services) for those individuals who are unfortunate enough to need care. It is important to note that insurance works only when there is broad participation and, in particular, only when individuals who are at low risk for illness participate (to counterbalance those who are at high risk for illness). The cost of insurance—the insurance premium—is set based on predicted expenses (the so-called actuarially fair value, to which administrative costs are added) for all individuals in the covered population; if only high-risk/high-cost individuals participate in the insurance pool, the cost of insurance is likely to be perceived as prohibitive (and, in fact, the primary objective of insurance—to pool risk—is lost).

Initially, health insurance in the United States was designed to protect against potentially catastrophic expense, in particular, the cost of hospitalization or other care that was not routine. Over time, though, insurance has evolved from a risk-mitigation strategy to a prepayment strategy; that is, more and more, health insurance in the United States is designed to cover not only unexpected and potentially catastrophic healthcare needs but predictable healthcare needs (for example, preventive services).

For example, many economists—including the author—argue that using insurance as a prepayment vehicle is not only inefficient (the economists’ term) but wasteful. If an individual expects to have a service (for example, a woman expects to have a mammogram), bundling it into insurance means that the price of insurance rises by the expected cost of the mammogram in addition to the administrative fee that is loaded on by the insurance administrator. Using insurance to prepay for the mammogram simply adds that administrative cost. That said, the coverage by insurance of routine (preventive) services is now almost universal. Despite the theoretical argument that coverage for preventive care is not a goal of insurance, the marketplace appears to have spoken: the role of insurance has evolved from pure risk mitigation to include prepayment. The market for healthcare purchasing is complex; arguments about the proper role of insurance require consideration that is beyond the scope of this chapter.

The Structure of Health Insurance

Health insurance establishes rules for paying for healthcare, but at the end of the day, the dollars that are disbursed through health insurance systems come from other sources. It is important to take a brief look at who pays for what.

To begin with, Americans purchase (or, in some cases, receive as an entitlement) health insurance; when they do, they pay an annual premium, which typically depends on their family structure (whether they are purchasing insurance for themselves or for their family) and the nature of the insurance they are purchasing. When they use that insurance (to purchase or, more accurately, to obtain reimbursement for healthcare services that are covered by that insurance), they may also face costs (which depend on the nature of the insurance), in particular, a deductible and a copayment. The insurance deductible is a sum (that is tied to the structure of the insurance policy and hence to its price) that the insured must pay for healthcare services before the insurer pays; in other words, it is a way of maintaining the original objective of insurance (to protect against very high costs). A deductible typically must be met on an annual basis so that insurance covers nothing until it is met, but once it is met, it need not be paid again in that year. In addition to the deductible, there is typically a copayment: the consumer’s share of the cost for every service that is reimbursable. Again, copayment levels vary across insurance contracts and clearly tie to price; the higher the copayment, the higher the consumer’s share of the cost of the service and (importantly) the more likely it is that the consumer will forego a high-cost service (or substitute a lower-cost service for that high-cost one). So, the purpose of a copayment is less to transfer payment (cost) from the insurer to the insured than it is to increase the sensitivity of the insured to the cost of service and—through that—reduce demand for services (and especially reduce demand for high-cost services).

Insurance in the United States

With the preceding brief overview of the nature and structure of insurance complete, we turn our attention to the insurance market in the United States.

There are three primary mechanisms through which Americans currently receive health insurance:

• Commercial (private) health insurance, which in the vast majority of cases is provided through an employer (employer-sponsored health insurance) but which can be purchased on an individual basis (typically at significantly higher cost). In 2015, the majority of Americans—approximately 214 million—were covered by private/commercial insurance programs,1 with the vast majority of those (about 178 million, or 83 percent) through employer-sponsored health insurance.

• The federally sponsored Medicare program, which provides an insurance benefit to the elderly (Americans 65 and older), as well as to those who are disabled and those with end-stage renal disease (ESRD). In 2015, Medicare insured approximately 51.9 million Americans.

• The Medicaid program, which is administered by the states but funded by both the state and federal governments and which provides an insurance benefit to the economically disadvantaged as well as to certain categories of women (especially pregnant women) and children (through Medicaid or through a similar program called the State Children’s Health Insurance Program [SCHIP], or now simply the Children’s Health Insurance Program [CHIP]). In 2015, these programs insured approximately 62.4 million Americans.

In addition, nearly 14.9 million Americans received health insurance/healthcare through the military healthcare system (including Tricare and programs offered by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs).

A significant number of Americans do not have health insurance. A major objective of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA or ACA)—President Obama’s landmark health-reform legislation—is to significantly reduce the number of Americans without health insurance, primarily through expansion of Medicaid but also through the application of an insurance “mandate” that increased participation of low-risk individuals who formerly opt out of the insurance market. In 2009, shortly before the ACA was signed into law, there were 50.7 million Americans without health insurance.2 By 2015, this number had decreased by 43 percent to 29 million.

ACA includes a requirement that individuals who do not have health insurance provided through their employer or another source (e.g., Medicare or Medicaid) purchase health insurance (or pay a penalty that the Supreme Court of the United States has recently declared “a tax”): the so-called individual mandate. Subsidies are provided to those who are least able to afford that insurance. A policy goal of that “mandate” clearly is to reduce the number of individuals who are uninsured (and thereby to increase their access to care), but it is also to increase the size of the insurance risk pool (so that risk is spread across a larger group) and therefore to reduce the cost of insurance to the individual by bringing into the insurance pool low-risk individuals who historically have opted out of the insurance system. (By bringing that group in, average risk—and hence the actuarially fair value, or price—declines.)

Insurance Products

It is necessary, before going into more detail about how publicly and privately funded insurance programs pay for care, to point out that there is a range of insurance “products” that differ significantly in ways that affect payment. Although there is more variation (and arguably more innovation) across products in the commercial/private market, this product variation appears in both Medicare and Medicaid. To summarize, five major types of products are prevalent in the United States:

• Traditional “open access”/fee-for-service (FFS) products, which allow those individuals who are insured to obtain care anywhere they choose and reimburse providers on the basis of charges.

• Preferred Provider Organizations (PPOs)/“tiered networks,” which allow individuals to receive care from a network of “preferred providers”—typically hospitals and physicians with whom discounts have been negotiated. PPO agreements may (or may not) permit individuals to obtain care outside of the preferred provider network—at significantly higher cost to the individual seeking care (through a higher copayment).

• Health Maintenance Organizations (HMOs), which significantly restrict access to care for insured individuals to a (typically relatively small) network of providers; which provide a range of value-added services, including care-management services intended to improve quality and reduce cost by supporting patient self-management, preventive care, and coordinated care; and which often reimburse providers not on a fee-for-service basis but on a capitated (per-member per-month) basis to create incentives among providers for fiscally responsible care.

• Point of Service (POS) plans, which allow individuals to choose (at the point of service) whether to seek care under the PPO or under the HMO. POS plans typically offer more choice than HMOs but require that a patient have a primary care physician (who serves as the “point of service contact”), so they typically offer less choice than a PPO.

• Health Savings Accounts (HSAs), High-Deductible Health Plans (HDHPs), Consumer-Directed Health Plans (CDHPs), and other products that transfer much more of the financial risk to the consumer. This is a heterogeneous and rapidly evolving portfolio of offerings that currently constitutes a small share of the insurance market but that may become more important as insurers seek ways to make consumers more sensitive to the cost of the healthcare services they purchase.

Each of the main structures of insurance programs in the United States will be described in the following sections.

Commercial (Private) Insurance in the United States

As noted, the majority of Americans receive health insurance through their (or a family member’s) employer; health insurance as a benefit of employment has been the predominant form for several decades. Employer-sponsored health insurance has its roots in the wage and price controls that were in place during World War II and in favorable treatment under the tax code: employers offered richer health insurance benefits to attract and retain employees when wages were controlled and have added to the value of that benefit because the dollars that are set aside for health insurance benefits are effectively tax-free income to employees.

Employer-sponsored health insurance can follow either of two distinct (although, for employees and their families, often indistinguishable) paths: employers may purchase health insurance from an entity that pools risk and administers the health insurance program, or the employer may self-insure (that is, bear the risk itself) and hire (typically a health insurance firm to serve as) a third-party administrator (TPA) of its health insurance program. The TPA administers not only the basic mechanics of the insurance program (such as enrollment, payment of claims to providers, or reimbursement of payments made by consumers) but also a wide array of programs designed to improve health and/or manage cost (ranging from efforts to select and guide consumers to high-quality, cost-effective providers to programs intended to support consumer efforts to manage their own health and illness—so-called care, or disease, management programs). Many large firms elect to self-insure; smaller firms (which are not able to pool risk over a large population) will more often purchase insurance (although as the cost of healthcare and therefore the actuarially fair price of health insurance rises, many firms with fewer than 50 employees are electing not to offer health insurance).

In either case, the health insurance benefit is typically structured as described earlier in the section “Insurance Products”: employees have a choice as to whether to purchase insurance (which is heavily subsidized, as a benefit, by the employer, but the employee still pays, on average, between 15 percent and 25 percent of the premium), and employees often (but do not always) have a choice among insurance providers and/or insurance plans.

Commercial insurance plans/products will differ with respect to the extent to which they offer choice among providers, with respect to the nature and extent to which there are programs available to support employee or employer health-related goals, and (based on those) with respect to their premium, deductible, and copayment costs. Most employer-sponsored plans cover “major medical” (hospital and ambulatory service providers); coverage of prescription drugs is common but not universal.

Commercial products are as briefly described earlier in the section “Insurance Products.” The near majority (about 48 percent) of workers were enrolled in PPOs in 2016,3 15 percent were in HMOs, 9 percent were in POS plans, and 29 percent were in higher-risk plans (HSAs, HDHPs, CDHPs, and the like). Only about 1 percent of workers were enrolled in conventional open-access plans.

The distribution of workers across insurance products reflects what has been, over the past decade or more, a corporate priority of the first order: to control healthcare costs. That only 1 percent of workers purchase health insurance that provides open access undoubtedly reflects both employers’ unwillingness to offer such open-access plans and the cost differentials that employees who choose them face. The preponderance of PPOs reflects the trade-off between choice and cost, which has been the conundrum; while PPOs offer significant choice among providers, there may be strong financial incentives to seek care in the PPO network so that choice is effectively constrained.

In the same way, the rapid growth of consumer-directed and high-deductible health plans—the penetration of which grew by more than 600 percent between 2006 and 2016 to nearly 30 percent—reflects employers’ interest in creating pressure for cost control, not by restricting access but by creating an incentive for employees and their families to purchase health services wisely. It seems very likely that this trend will continue—as will innovations in payment beyond discounted fee-for-service plans; current trends are discussed in the earlier section “Insurance Products.”

Medicare

Medicare is the insurance program for Americans older than 64; it covers, as well, Americans who are disabled (receiving Social Security Disability Insurance for 24 months), including those disabled by Lou Gehrig’s Disease and those with end-stage renal disease, which oftentimes requires dialysis.

Medicare pays for healthcare in two ways. The majority (nearly 70 percent) of beneficiaries choose to enroll in traditional Medicare, which reimburses for care on a fee-for-service basis.4 The remainder enroll in Medicare Advantage (managed healthcare; so-called Medicare Part C) plans, which collect premiums from Medicare (on a risk-adjusted capitated basis; that is, they are paid a per-member per-month [PMPM] fee by Medicare and pay physicians, hospitals, and others providers on an FFS or PMPM basis for care of the beneficiaries that they manage with that premium).

Medicare FFS operates through three distinct benefit programs:

• Medicare Part A Hospital insurance and covers inpatient and, in some cases, convalescent care in skilled nursing facilities. In the past, Medicare paid hospitals based on charges for every service provided. With rapid cost inflation, Medicare introduced a fixed-priced “episode-based” payment system using diagnosis-related groups (DRGs) in the 1980s and updated to Medicare Severity diagnosis-related groups (MS-DRGs) in October 2007. MS-DRGs are severity and case-mix adjusted, and most MS-DRGs account for complications. MS-DRG rates are updated regularly to assure that payment reflects changes in cost (as may, for example, follow the introduction of new technology related to the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health [HITECH] Act). MS-DRGs are intended to capture the bundle of services typically provided to patients with specific conditions/receiving specific procedures/with specific predictable needs—for example, patients with pneumonia or who have a stroke or who have a joint replacement procedure. Paying the hospital a fixed fee for the bundle of services typically provided to such patients creates an incentive for hospitals to improve efficiency (and, in particular, to reduce the use of unnecessary, marginally valuable, or unnecessarily high-cost services). Because MS-DRGs are set at the average cost for patients of a given type, hospitals will lose money on some patients (who have above-average service needs) but will make money on others (who have below-average service needs). For hospitals with reasonable volumes, the expectation is that (on average) MS-DRG prices are fair.

• Medicare Part B Major medical; that is, it pays for covered services that are not included under Part A (or medications, covered in the next bullet). In general, it covers ambulatory services (including physician services) and durable medical equipment (a major expense in the Medicare population).

Medicare pays physicians and other qualified providers on an FFS basis, where fees are set (a Medicare fee schedule) based on a resource-based relative value scale (RBRVS). The RBRVS is an effort to estimate the resources required to deliver a given service (described by a code called a current procedural terminology [CPT] code; CPT codes in most cases define the billable service). These are defined in Chapter 13. Medicare’s fee for a given service—the price it pays providers—is the product of the relative value units (RVUs) associated with that service (the CPT code for that service) and a “conversion factor,” which effectively assigns a dollar value to an RVU. The RBRVS is updated annually by an RBRVS update committee (the RUC) that is composed of 29 physicians—through a process that is often contentious because adjustments to the RBRVS are effectively a zero-sum game (an increase in the value of one service means that another service must be reduced in value).

• Medicare Part D Covers medications; it was introduced as part of the Medicare Modernization Act of 2006. Medicare beneficiaries are eligible to obtain Part D benefits through stand-alone prescription drug plans (PDPs) or bundled with the Part C benefit (through a Medicare Advantage managed care plan). Unlike Part A and Part B (which provide standard benefits to all beneficiaries), PDPs (and MA PDPs) are able to offer a wide variety of pharmacy benefits—more or less inclusive, more or less generous, at different price points—to offer Medicare enrollees many options. Exceptions include medications administered in an ambulatory setting; for example, chemotherapy administered intravenously to a patient with cancer in a physician’s office or day hospital is reimbursed under Part B, at 106 percent of the average sales price. In some cases, there has been concern that the number of options is overwhelming and that beneficiaries cannot understand what plan might be best suited for them.

Medicaid

Medicaid is a public insurance program available to low-income Americans including children, pregnant women, parents, seniors, and individuals with disabilities. It is jointly funded by federal and state governments but fully administered by states. The federal government provides a percentage (known as the federal medical assistance percentage [FMAP]) of the funding of each state’s Medicaid budget. FMAPs vary across states and are determined by criteria such as a state’s per-capita income. By law the minimum FMAP is 50 percent (a one-to-one match), and the maximum is 83 percent. In 2016, Mississippi has the highest FMAP at 74.17 percent. Thus, for every $1 contributed by Mississippi to Medicaid, the federal government contributes $2.87.5

While there are minimum federal standards to which states must adhere in their eligibility rules and covered services, states have some liberty in the designs of their Medicaid programs through the use of waivers. Mandatory populations include children under age 6 below 133 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL), older children below 100 percent FPL, pregnant women below 133 percent FPL, and elderly and disabled Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) and Supplemental Security Income (SSI) beneficiaries below 74 percent FPL. However, the ACA permits states to opt into expanding their Medicaid eligibility to all citizens below 138 percent FPL including working parents and childless adults. Mandatory benefits include inpatient and outpatient hospital services, physician services, nursing facility services, and home health services. Many states use waivers to expand their covered populations (e.g., have higher FPL thresholds) and covered services (e.g., prescription drugs, clinic services, and hospice services). In 2001, only about 40 percent of Medicaid expenditures were spent on mandatory services for mandatory populations.6

Like Medicare, Medicaid reimburses for care through two payment mechanisms: FFS and managed-care arrangements. Some states are also adopting integrated-care delivery models. Working within federal guidelines and approval, states design their reimbursement methodology. When determining their reimbursement rates for FFS, states may base them upon the costs of providing the services, the reimbursement rate of commercial payers in the private market, and/or a percentage of the reimbursement rate of Medicare. The reimbursement rate of Medicaid is typically significantly lower than that of commercial payers and Medicare.

States can make managed care enrollment voluntary or can seek a waiver from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) to require enrollment in a Managed Care Organization (MCO). Currently, most states have waivers to implement mandatory managed care in parts of their states or for certain categories of beneficiaries or to implement statewide mandatory managed-care enrollment as part of a demonstration.7 Thus, the national Medicaid MCO enrollment rate is significantly higher than that of Medicare. Some states have managed-care enrollments rates that are 100 percent (Hawaii and Tennessee), and in other states the Medicaid population is covered under different delivery systems.8

Medicaid’s Role in Long-Term Care

Because of its inclusion of low-income elderly, its coverage of nursing home care and home healthcare, and the unpopularity of long-term care (LTC) insurance, Medicaid is a major player in the financing of long-term care. Fifty-one percent of all long-term care is funded through Medicaid.9 In 2014, 25 percent of Medicaid expenditures purchased long-term care.10 The quick growth in the percentage of Medicaid dollars spent on LTC has led to legislative attempts to contain the growth, such as the development of an LTC prospective payment system based on MS-DRGs (vs. the previous fixed rates), certificate-of-need laws for the construction of nursing homes, and regulations on the “spending down” of wealth by the elderly to qualify for Medicaid.

Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP)

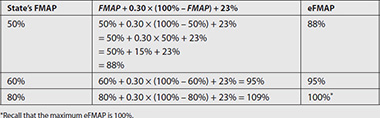

Title XXI of the Balanced Budget Act of 1997 established the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), formerly known as State Children’s Health Insurance Program (SCHIP). This program is designed to provide health insurance for children from low-income households that earn too much to qualify for traditional Medicaid. Like Medicaid, CHIP is administered by states but funded jointly by federal and state governments. States receive an enhanced federal medical assistance percentage (eFMAP) to fund CHIP. The CHIP eFMAP is typically higher than the Medicaid FMAP (see Use Case 3-1). States that cover children with greater than 300 percent FPL receive their FMAP only for CHIP federal matching. However, unlike traditional Medicaid, federal dollars for CHIP are capped. Thus, each state is allocated part of this amount and must supply matching funds according to its FMAP.

Use Case 3-1: FMAP and eFMAP Rates

As mentioned in the text, Medicaid and CHIP are jointly funded by the federal and state governments. For both programs, the federal government provides a percentage of the funds. The percentages vary across states. FMAP is the federal government’s contribution percentage toward a state’s Medicaid program, and eFMAP is the contribution percentage toward a state’s CHIP program. While the FMAP and eFMAP are not equal, there is a mathematical relationship between the two. A state’s eFMAP is never less than its FMAP. The amount of additional percentage points of the eFMAP is equal to 30 percent of the difference between a state’s FMAP and 100 percent. Furthermore, for years between 2016 and 2019, the ACA provides an additional 23 percentage points of eFMAP. This provision in the ACA also increases the maximum eFMAP from 85 percent to 100 percent. The following equation more clearly demonstrates the ACA-augmented relationship between the two rates:

eFMAP = min[FMAP + 0.30 × (100% − FMAP) + 23%, 100%]

For individuals who were eligible for Medicaid prior to the ACA’s Medicaid expansion, the FMAP of a state is determined by a comparison between the state’s per capita income and the nation’s per capita income using the formula in the following table. However, this FMAP must be at least 50 percent and less than 83 percent. For individuals who are newly eligible for Medicaid due to the ACA Medicaid expansion, the FMAP from 2014 through 2016 is 100 percent and will decrease each year thereafter until it reaches 90 percent in 2020.

Uncompensated Care

Although healthcare providers are compensated for the majority of their services through commercial insurance, public insurance, or private payments, they do not receive payments for a significant portion of their services. This care is known as uncompensated care. There are two sources of uncompensated care: charity care and bad debt. Charity care is care for which the provider never expected compensation because the patient was determined to be unable to pay. Bad debt is defined as services for which the provider expected reimbursement due to the insurance and/or financial status of the patient. Inability to collect the funds may result from an inability to collect copayments and/or deductibles from insured patients, or to collect full payment from uninsured patients whose financial situation does not officially qualify them for charity care. Eligibility for charity care usually depends on factors such as individual and family income, assets, employment status, and the availability of alternative sources of funds.

Given the existence of the Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act, which mandates all emergency rooms to provide stabilizing care to patients with emergency conditions regardless of their ability to pay, and state laws such as New Jersey’s N.J.S.A. 26:2H-18.64, which makes it illegal for any hospital to “deny any admission or appropriate service to a patient on the basis of that patient’s ability to pay or source of payment,” uncompensated care is an expected part of the healthcare system. Coughlin et al. estimate that uncompensated care in the United States totaled $84.9 billion in 2013. Hospitals bear the bulk of these losses (60 percent), while physicians and clinics evenly split the remaining portion.11 The AHA estimates that between 1990 and 2014, uncompensated care as a percentage of all hospital expenses has ranged between 5.3 and 6.2 percent.12

Hospitals typically do not write off the costs associated with uncompensated care. Rather, federal and state direct service programs reimburse hospitals via state and local tax appropriations and/or cost-shifting to private payers. This means that uncompensated care is a problem that extends beyond providers and nonpaying patients.

One strategy that hospitals and physicians have tried to use to recover losses associated with uncompensated care (as well as to make up shortfalls when Medicaid payment rates fall below the providers’ actual cost) is to raise prices to private payers. While providers do not have the ability to set prices unilaterally, they generally have more opportunity to negotiate with private payers than with Medicare and Medicaid. This “cost-shifting” raises insurance premiums, which ultimately is transmitted back to the employers who pay the largest portion of those premiums. This has an impact on their costs (therefore their profitability)—and is a force that can discourage smaller employers from offering health insurance. It also drives them to shift costs directly to their employees—through higher premiums, higher deductibles, and higher copayments. Cost-shifting is a serious concern, in a setting in which providers may be seeking to increase the revenue they derive from private payers, as public payers (Medicare and Medicaid) seek to reduce their costs. Shifting costs from Medicare to the private sector may preserve the Medicare Trust Fund—but it does not improve the efficiency of the healthcare system in the United States.

While cost-shifting is a significant concern, providers have other sources to cover the expenses related to the majority of their uncompensated care. In 2013, federal, state, and local governments did not fund 38 percent of the uncompensated care.11 The largest sources of funding for uncompensated care are Disproportionate Share Hospital payments/adjustments through the Medicare and Medicaid programs. Hospitals that treat a large number of Medicaid, low-income, and uninsured individuals receive these payments, which help to preserve Medicare and Medicaid patients’ access to care.

Trends in Payment/Payment Reform

Intense pressure on all payers—employers, the states, and the Medicare Trust Fund—has driven innovations in payment. These innovations have moved at a somewhat different pace across those three sectors. In general, the private sector has more aggressively sought change than have governments (both state and federal), but changes in the way the government pays for care (and, especially, changes in the way Medicare pays for care) have much more impact, given the scale of public programs.

The ACA established the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (CMMI), also called the CMS Innovation Center, to test innovative healthcare delivery and payment models. One CMMI initiative is the State Innovation Models (SIM) Initiative in which states receive funds to implement various enabling strategies to transform the healthcare systems within their states. Each of the participating 6 SIM Round One Model Test states and 11 SIM Round Two Model Test states are supporting alternative payment models as part of their SIM initiatives.

The Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act (MACRA) is another mechanism through which the government incentivizes the implementation of alternative payment models. Passed in 2015, MACRA provides bonus Medicare payments to providers who have significant participation (measured by healthcare dollars or patient count) in alternative payment models.

While there have been a number of innovations in payment over the years, alternative payment models can be grouped into three major categories:

• Pay-for-performance (P4P)/provider incentive programs

• Episode-based, or bundled, payment

• Payment reform coupled to delivery system innovation

Pay-for-Performance (P4P)/Provider Incentive Programs

Pay-for-performance programs are incremental innovations off of a fee-for-service payment platform. The idea of P4P is simple: the payer (private or public) offers providers additional payment for achieving performance targets, which are designed to improve quality but also achieve long-term reductions in cost. There are, for example, many short-term or physiologic health outcomes—hemoglobin A1c in patients with diabetes or cholesterol in patients with (or at high risk for) coronary artery (heart) disease—for which a strong logical case (and, in some cases, a data-driven empirical case) can be made that investing in care to achieve better outcomes will lead to improved health and lower total cost over time. By creating an incentive for providers to achieve health-related outcome targets, health can be improved (and costs controlled).

The introduction of P4P programs had to wait for the development and diffusion of quality metrics that could support the setting of performance targets. That was led by the Joint Commission and the National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA) through the development and deployment of a set of standard metrics for hospitals (ORYX) and health plans (the Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set [HEDIS]). HEDIS metrics—which include statistics that address clinical quality, member satisfaction, and utilization (and will likely include measures of efficiency in the future)—permitted employers (and their employees) to select health plans (initially HMOs, but over time PPOs as well) based on both price and quality (“value”) rather than on price alone. But they also permitted the setting of performance targets, which strategy has diffused, over time, both to the interface with providers and to the public sector. So, for example, P4P has diffused rapidly into FFS arrangements with physicians and hospitals in the private sector.13 The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services has introduced quality payment differentials to hospitals based on hospital scorecards and has begun to introduce quality incentives to physicians through the Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS; initially, the Physician Quality Reporting Initiative [PQRI]). That said, the performance of P4P programs (for achieving real improvements in value) has been described as “lackluster.”14 So, policymakers—in both the public and private sectors—have sought more powerful payment reforms.

Episode-Based, or Bundled, Payment

Many would argue that any payment innovation that begins with FFS—that is, a system that intrinsically motivates the delivery of more, and more intensive, care—will not achieve the results necessary to create a sustainable, high-performing healthcare system in the United States.14 As a result, there have been innovations that begin with a radically different approach to payment—one that creates incentives that are in the opposite direction of FFS (and hence drives intrinsically toward lower cost).

Such approaches “fix price.” That is, they are designed to provide a fixed fee that will cover all services (defined in some way) rather than reward the provider for each service independently. The first—and arguably strongest—such payment innovation is capitation, which is payment of a fixed amount on a per-member per-month basis for all services a member may require.

Capitation was prevalent in the early 1990s, with the introduction of HMO-style managed care. And capitation continues to be prevalent, at the point at which employers (and/or governments) pay health plans.

But capitation did not work well at the physician level—for many, many reasons. Physicians, especially in the early 1990s, were inexperienced with (and lacked the tools they needed to manage) the clinical risk that accompanied the financial risk inherent in capitation, and physicians have limited control over costs (for example, once a patient is hospitalized). So—although we may see and are, in fact, seeing capitation of providers reemerge (see the section “The Accountable-Care Organization”)—there have been efforts to create payment strategies that are more discrete (and clinically manageable) than capitation.

Important among those are episode-based, or bundled, payments. The notion of a bundled payment is to offer a fixed fee—not for all services that a patient may require in a month (or over a year) but for the set of services a patient typically requires when they have a particular condition or procedure. To the extent that care is predictable for (for example) patients who are having elective surgery, or even for patients with conditions like diabetes, it should be possible to predict the needs (and therefore the costs) for patients during the course of a specific episode of care.

This is not a new idea; in fact, as discussed previously, it is the foundation of Medicare’s DRG system for paying for hospital care, and it is the basis for which Medicare pays for outpatient dialysis for patients with ESRD. But what has emerged is broadening the scope of payment bundles and extending the “bundle” from the inpatient (or facility) stay (alone) to an interval that includes both pre- and post-hospital care. By setting a fixed fee for a bundle that includes, in particular, post-discharge events, the provider bears risk for the costs that would follow an adverse outcome (such as a complication requiring significant ambulatory care or even a rehospitalization). So, the bundled payment creates a potentially strong incentive to optimize pre-hospital care (so that the patient is well prepared and the hospital stay can be minimized), to optimize care over the inpatient stay itself (so that the patient is not discharged prematurely and does not develop a complication or return to the hospital), and to optimize the post-discharge interval (so that gains achieved in the hospital are maintained and the discharge plan carefully executed).

There is considerable interest in, and innovation regarding, bundled payment. In the private sector, some provider organizations (notably, Geisinger Health System in Danville, Pennsylvania) have moved proactively to offer fixed-price bundles to payers (through their ProvenCare program).15 There are private-sector pilots underway in many parts of the country to evaluate bundled payment strategies that may be more realistic in markets in which provider organizations have not achieved the level of integration that Geisinger has; notable pilots include those led by PROMETHEUS Payment in five sites across the country and those led by the Integrated Healthcare Association (IHA) in California. That said, bundled payment remains, as of 2016, the exception and not the rule in the private sector.

Medicare has tested bundled payment strategies in two large demonstrations: one in the 1990s (the Medicare Participating Heart Bypass Center Demonstration)16 and one that began in 2009 (the Acute Care Episode Demonstration).17 In addition, CMMI is currently implementing the Bundled Payment for Care Improvement initiative,18 which offers organizations the opportunity to test a broad range of approaches to bundled payment. Furthermore, several states are supporting episode of care models with their SIM Initiative funding. Finally, Section 2704 of the ACA establishes a demonstration project for Medicaid programs in up to eight states to evaluate bundled payments. So, the expectation is that there will be, in the public sector, testing and evaluation of bundled payment approaches, but it may be some time before they have moved into the mainstream.

Payment Reform Coupled to Delivery System Innovation

A primary objective of payment reform (including P4P and bundled payment) is to drive changes in the processes through which care is delivered—to increase coordination, eliminate redundancy, and thereby enhance quality and eliminate waste. That transformation of the care-delivery system will almost certainly require some restructuring of it. So, I expect—and in fact have seen—changes in the structure of the healthcare marketplace, where payment reform is underway.

On the other hand, there has been innovation in the delivery system, driven by the primary interest providers have in improving the quality and efficiency of care. The risk in such innovation is that it will in fact improve efficiency—so that providers that operate in an FFS environment will (as a consequence) see their revenue and profits fall.19

As a result, there is a clear need to link delivery system innovation to payment reform. There are two important delivery system innovations that are now linked to payment reform:

• The patient-centered medical home (PCMH)

• The accountable-care organization (ACO)

The Patient-Centered Medical Home (PCMH) The PCMH is a “health care setting that facilitates partnerships between individual patients, and their personal physicians, and when appropriate, the patient’s family, with the goal of providing comprehensive primary care for children, youth and adults.”20 Originally conceived and advanced by the medical societies representing the primary care disciplines (the American Academy of Pediatrics, the American Academy of Family Physicians, the American College of Physicians, and the American Osteopathic Association),21 the concept has been embraced widely—at least among those who pay for healthcare.

The detailed requirements that describe a PCMH can be found elsewhere;22, 23 what is important for the purposes of this discussion is that the providers must invest (significantly) in the infrastructure (including the HIT infrastructure) required to achieve the functionality, which is the PCMH. The rate at which the PCMH concept diffused was limited by the lack of a return on that investment. In response, many private payers have begun to offer a per-member per-month fee to practices that are certified PCMHs, which recognizes the additional capabilities (to improve care and reduce cost) that are expected in practices that achieve that recognition. That (patient management) fee is in addition to the FFS payment the practice earns when it sees a patient; the expectation is that a patient (or “case”) management fee will be more than recovered through reductions in expenditures for other healthcare services (such as inpatient hospital stays).

Medicare tested the PCMH through two demonstrations: the Multi-Payer Advanced Primary Care Practice (MAPCP) Demonstration and the Federally Qualified Health Center (FQHC) Advanced Primary Care Practice (APCP) Demonstration. In addition, CMMI tested the PCMH model through a Comprehensive Primary Care (CPC) initiative that provides for multipayer support of primary care practices to support their efforts to offer more effective and coordinated primary care. Building upon CPC, CMMI is testing another multipayer PCMH-based model known as Comprehensive Primary Care Initiative Plus (CPC+). Finally, PCMHs are being evaluated at the state level (for example, in addition to the eight MAPCP states, a multipayer initiative in Maryland).24 The PCMH model is one of the most popular healthcare delivery models that SIM Model Test states are supporting in their initiatives. Given this level of interest in the PCMH model, one can expect that, at least in the short run, payment of a PMPM management fee to qualified PCMHs will be more prevalent and a more important part of the revenue stream for primary care practices.

The Accountable-Care Organization

The system for delivering healthcare in the United States is poorly organized, with weak relationships among the many providers and sites at which patients receive care. As a result, care is poorly coordinated and often redundant, patient outcomes suffer, and precious resources are wasted.

Many believe that solving this problem requires the creation of strong incentives and the infrastructure needed to drive care coordination and integration across providers. This has led to the articulation of the concept of an accountable-care organization (ACO). While ACOs are defined in different ways, what is common to all definitions—and is at the core of the concept—is that it is a delivery system entity that is prepared to accept accountability for the clinical and financial outcomes of the patients to whom it delivers care.

ACOs are emerging in both the public and private sectors.25 There are two especially important innovations that link ACOs to changes in Medicare payment, described next. However, it should also be noted that CMS is taking its experience from these two initial ACOs to implement the Next Generation ACO Model in 2017.

• Medicare Shared Savings Program (MSSP) A payment innovation linked to the operations of ACOs.26 The program was mandated by the ACA (though participation is voluntary), regulations describing the program were released in late 2011, and delivery systems began participating in 2012. Participation requires the creation of an entity that includes primary care physicians (and typically includes hospitals). As of January 2016 there were 433 MSSP ACOs.27 Each ACO is paid on a discounted FFS basis (and providers that are part of the ACO are paid by the ACO according to agreements that operate within the ACO) but Medicare shares “savings” that are derived from the ACO’s efforts to deliver high-quality, coordinated, cost-effective care. “Savings” are calculated as the difference between what spending would have been (for those Medicare enrollees for whom the ACO is responsible) and what spending actually was, adjusted for factors that are beyond the control of the ACO. The ACO’s share of savings depends on a number of factors, including (very importantly) how the ACO performs on a set of quality metrics designed to assure that savings are not generated by withholding (or “stinting”) on care.

The MSSP ACO is, then, a delivery system innovation tightly linked to a change in the way care is paid for. In its current form, it builds off of an FFS payment model; it is, in some ways, “simply” a P4P program with strong incentives to achieve financial as well as quality performance targets, and it operates to create incentives across provider types (in particular, to align incentives for hospitals and physicians). It is important to note that, in the best case, ACO revenue will be less than pure FFS revenue. (The ACO incentive is to reduce Medicare’s cost relative to projected FFS cost in a given year; to the extent that it does, it receives some share—up to 50 percent—of that difference. But that will always be less than it would have received had there been no ACO.) So, the ACO is able to succeed economically only if it can reduce production cost more than it reduces billings. This has proven to be a challenge for many organizations.

• Pioneer ACO Program (Pioneer)28 An alternative to the MSSP. Unlike the MSSP (which is not a pilot or demonstration; any organization that qualifies can participate), Pioneer is a pilot run out of CMMI; 32 organizations were originally selected in 2011 on a competitive basis (9 Pioneer ACOs remained in 2016) to operate as ACOs in a payment environment that creates much greater opportunities for shared savings (but also much greater downside risk in the event that savings are not realized) but also intentionally moved toward a “population-based payment model” (that is, a per-member per-month payment; previously called capitation) that creates even more powerful incentives for cost control. Like the MSSP, there are strong protections to assure quality; in addition, there are incentives to encourage Medicare Pioneer ACOs to develop performance-based payment arrangements with other payers.

The Pioneer program represents an important opportunity to allow healthcare organizations that have developed advanced care management/care coordination infrastructure to capture the financial gains associated with the effective use of that infrastructure. The Pioneer program sends a signal that CMS understands that there is a need to consider a move away from FFS Medicare, if Medicare is to achieve its triple aim of better care, better health, and lower cost.

Chapter Review

This chapter described the complex systems through which healthcare is paid in the United States. In particular, it described how insurance works and how costs are shared by the ultimate payers of care (the federal and state governments, employers, and individual Americans themselves), and it expanded on the main structures of programs. The chapter defined the major payers and the types of insurance products offered. Finally, the chapter discussed changes in the way care is paid for and delivered as part of healthcare reform or that may be accelerated by healthcare reform in the future.

Questions

To test your comprehension of the chapter, answer the following questions and then check your answers against the list of correct answers at the end of the chapter.

1. Which of the following is true?

A. Individuals pay a relatively small percentage of the annual cost of their insurance.

B. Individuals pay a copayment that is a relatively small percentage of the cost of most services they use.

C. Individuals with private health insurance—particularly those with employer-sponsored health insurance—pay (and are likely to pay in the future) a larger share of the cost associated with their healthcare than individuals with Medicare or Medicaid.

D. All of the above.

2. Which of the following are not insurance products commonly offered in the United States?

A. Traditional/open-access health insurance plans

B. Preferred Provider Organizations (PPOs) and Health Maintenance Organizations (HMOs)

C. Independent Practice Associations (IPAs) and Patient-Centered Medical Homes (PCMHs)

D. Consumer-Directed Health Plans (CDHPs) and Health Savings Accounts (HSAs)

3. Which of the following is true of the Medicare program?

A. All Americans older than 64 must participate.

B. The distribution of its beneficiaries across insurance products is very different from private insurance.

C. It has, since its inception, covered hospital care, ambulatory care, and prescription drugs.

D. All of the above.

4. In general, how does Medicare pay physicians?

A. Based on what physicians charge

B. Based on fees that are negotiated with physicians

C. Based on a fee schedule that is based on the resources required to deliver different services

D. On a capitated (per-member per-month [PMPM]) basis

5. In general, how does Medicare pay hospitals?

A. Based on what hospitals charge for each service they provide

B. Based on fees that are negotiated with hospitals for each service they provide

C. Through a shared savings program that rewards hospitals for saving money

D. Through a “bundled payment” system that offers a fixed price for all hospital services delivered during a hospital stay

6. Which of the following is true?

A. Accountable-care organizations (ACOs) are delivery system entities that are emerging in response to financial incentives to reduce the cost and improve the quality of healthcare.

B. Patient-centered medical homes (PCMHs) are nursing homes that are designed to assist patients to make the transition from hospital care to home care.

C. The Medicare Shared Savings Program (MSSP) is a way that Medicare beneficiaries can share in savings that derive from their efforts to take better care of themselves.

D. Bundled payment programs are an exciting innovation, but to date there is very little experience with them.

7. Which of the following is true of the insurance mandate in the Affordable Care Act?

A. It will mean that the federal government and the states will no longer need to provide Medicaid.

B. One of its goals was to increase the efficiency of insurance by bringing more (and lower-risk) Americans into the insurance risk pool.

C. It is unconstitutional, because the federal government cannot require Americans to buy anything (even health insurance).

D. It does not support delivery system innovations such as ACOs.

8. Given the ACA supplement, what is the minimum FMAP that will qualify a state for the maximum eFMAP?

A. 83%

B. 67.14%

C. 85%

D. 100%

Answers

1. D. Individuals with private insurance typically pay less than 25 percent of their annual premium, and Medicare and Medicaid enrollees pay less than that. Similarly, copayments—though rising and often perceived as high—are typically far less than the cost of the service provided. As costs (and therefore insurance premiums) rise, insurance products are evolving to shift costs to individuals, both to reduce the employer (or public) contribution to care and to create an incentive for individuals to use care wisely.

2. C. IPAs are groups of individual physicians and medical practices that provide services to managed-care organizations. PCMHs are medical practices that have put in place the infrastructure needed to coordinate care. IPAs and PCMHs will often contract with managed-care organizations (in particular, PPOs and HMOs), but they do so to provide care (not to provide insurance).

3. B. Traditional (open-access, FFS) care dominates Medicare. That is very rare in the private sector. The distribution of its beneficiaries across insurance products is very different from private insurance.

4. C. Physicians are paid based on the Medicare fee schedule, which in turn is based on a resource-based relative value scale (RBRVS).

5. D. Medicare has paid hospitals for more than two decades using diagnosis-related groups (DRGs) that cover hospital—but not physician—services provided during a hospital stay. Increasingly, hospital reimbursement can be enhanced (or threatened) by quality performance. The Medicare Shared Savings Program (MSSP) is a voluntary program that gives hospitals (through establishing accountable-care organizations) the opportunity to improve profitability by generating savings (but only if they reduce their own production costs as well).

6. A. PCMHs are primary care practices, with infrastructure designed to coordinate care (primarily ambulatory care, although transitions from hospital to home are important as well); they are not nursing homes. The MSSP is a program that permits providers (and, in particular, ACOs)—not patients/beneficiaries—to share savings with the Medicare program. There is considerable experience with bundled payments already—through hospital DRGs and through Medicare and private-sector pilots and demonstrations from the 1990s and early twenty-first century.

7. B. The Affordable Care Act intended to increase the efficiency of insurance by bringing more (and lower-risk) Americans into the insurance risk pool.

8. B. Between 2016 and 2019 the maximum allowed eFMAP is 100 percent; thus, to find the answer, the following algebra equation must be solved for x:

x + 0.30 × (100% − x) + 23% = 100%

References

1. U.S. Census Bureau. (2016). Coverage numbers and rates by type of health insurance: 2013 to 2015 (Table 1). Accessed on October 11, 2016, from www2.census.gov/programs-surveys/demo/tables/p60/257/table1.pdf.

2. DeNavas-Wall, C., Proctor, B. D., & Smith, J. (2010). Income, poverty, and health insurance coverage in the United States: 2009. Accessed on October 11, 2016, from www.census.gov/prod/2010pubs/p60-238.pdf.

3. Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF). (2016, Sept. 14). 2016 employer health benefits survey. Accessed on October 11, 2016, from http://kff.org/report-section/ehbs-2016-summary-of-findings/.

4. KFF. (2016, May 11). Medicare advantage. Accessed on October 11, 2016, from http://kff.org/medicare/fact-sheet/medicare-advantage/.

5. KFF. (2016). Federal medical assistance percentage (FMAP) for Medicaid and multiplier. Accessed on October 16, 2016, from http://kff.org/medicaid/state-indicator/federal-matching-rate-and-multiplier/?currentTimeframe=1&sortModel=%7B%22colId%22:%22FMAP%20Percentage%22,%22sort%22:%22desc%22%7D.

6. Henry Kaiser Foundation Medicaid overview. (n.d.). Accessed on September 8, 2012, from www.kff.org/medicaid/upload/Medicaid-An-Overview-of-Spending-on.pdf. [However, this page is no longer available to access].

7. Paradise, J., & Musumeci, M. (2016, June 9). CMS’s final rule of Medicaid managed care: A summary of major provisions. Accessed on October 18, 2016, from http://kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/cmss-final-rule-on-medicaid-managed-care-a-summary-of-major-provisions/.

8. KFF. (2016). Share of Medicaid population covered under different delivery systems. Accessed on October 18, 2016, from kff.org/medicaid/state-indicator/share-of-medicaid-population-covered-under-different-delivery-systems/?currentTimeframe=0&sortModel={“colId”:“Location”,“sort”:“asc”}.

9. Reaves, E. L., & Musumeci, M. (2015, Dec. 15). Medicaid and long-term services and supports: A primer. Accessed on October 11, 2016, from http://kff.org/medicaid/report/medicaid-and-long-term-services-and-supports-a-primer/.

10. KFF. (2015). Distribution of Medicaid spending by service. Accessed on October 11, 2016, from http://kff.org/medicaid/state-indicator/distribution-of-medicaid-spending-by-service/?dataView=1¤tTimeframe=0&sortModel=%7B%22colId%22:%22Location%22,%22sort%22:%22asc%22%7D.

11. Coughlin, T. A., Holahan, J., Caswell, K., & McGrath, M. (2014). Uncompensated care for uninsured in 2013: A detailed examination. Accessed on October 11, 2016, from https://kaiserfamilyfoundation.files.wordpress.com/2014/05/8596-uncompensated-care-for-the-uninsured-in-2013.pdf.

12. American Hospital Association. (2016, January). Uncompensated hospital care cost fact sheet. Accessed on October 11, 2016, from www.aha.org/content/16/uncompensatedcarefactsheet.pdf.

13. Schneider, E., Hussey, P. S., & Schnyer, C. (2011). Payment reform: Analysis of models and performance measurement implications. Technical Report. RAND Corporation.

14. Rosenthal, M. B., Landon, B. E., Norman, S. L. T., Frank, R. G., & Epstein, A. M. (2006). Pay for performance in commercial HMOs. New England Journal of Medicine, 355, 1895–1902.

15. Geisinger. (n.d.). ProvenCare by Geisinger ensures quality care comes standard. Accessed on October 18, 2016, from www.geisinger.org/sites/provencare/.

16. Cromwell, J., Dayhoff, D. A., McCall, N. T., Subramanian, S., Freitas, R. C., Hart, R. J., … Stason, W. (1998). Medicare participating heart bypass demonstration, executive summary. Final Report. Waltham, MA: Health Economics Research.

17. CMS Innovation Center. (n.d.). Medicare Acute Care Episode (ACE) demonstration. Accessed on October 18, 2016, from https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/ACE/.

18. CMS Innovation Center. (n.d.). Bundled payments for care improvement (BPCI) initiative: General information. Accessed on October 18, 2016, from https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/bundled-payments/index.html.

19. Pham, H. H., Ginsburg, P. B., McKenzie, K., & Milstein, A. (2007). Redesigning care delivery in response to a high-performance network: The Virginia Mason Medical Center. HealthAffairs, 26(4), 532–544. Accessed on October 18, 2016, from http://content.healthaffairs.org/content/26/4/w532.full.pdf+html.

20. Patient-Centered Primary Care Collaborative (PCPCC). (n.d.). Defining the medical home. Accessed on October 18, 2016, from www.pcpcc.org/about/medical-home.

21. Sia, C., Tonniges, T. F., Osterhus, E., & Taba, S. (2004). History of the medical home concept. Pediatrics, 113(5), 1473–1478.

22. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). (n.d.). Defining the PCMH. Accessed on October 18, 2016, from https://pcmh.ahrq.gov/page/defining-pcmh.

23. HHS, AHRQ. (n.d.). PCMH citations collection. Accessed on October 18, 2016, from https://pcmh.ahrq.gov/citations-search?search_api_views_fulltext=PCMH.

24. Maryland Health Care Commission. (n.d.) Maryland Multi-Payor Patient Centered Medical Home Program. Accessed on October 18, 2016, from http://mhcc.maryland.gov/pcmh.

25. Mostashari, F., & Colbert, J. (2014, May 12). How community health centers are taking on accountable care for the most vulnerable. Accessed on October 18, 2016, from www.brookings.edu/blog/up-front/2014/05/12/how-community-health-centers-are-taking-on-accountable-care-for-the-most-vulnerable/.

26. CMS. (n.d.). Medicare Shared Saving Program. Accessed on October 18, 2016, from www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/sharedsavingsprogram/index.html.

27. CMS. (2016, April). Fast facts: All Medicare Shared Savings Program (Shared Savings Program) ACOs. Accessed on October 11, 2016, from www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/sharedsavingsprogram/Downloads/All-Starts-MSSP-ACO.pdf.

28. CMS Innovation Center. (n.d.). Pioneer ACO model. Accessed on October 18, 2016, from https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/Pioneer-ACO-Model/index.html.

*This chapter updates Chapter 2, by Cary Sennett and Donald Nichols, in Healthcare Information Technology Exam Guide for CompTIA® Healthcare IT Technician & HIT Pro Certifications (McGraw-Hill Education, 2013). The author acknowledges the contributions of Cary Sennett in the first edition.