CHAPTER 20

EHR Implementation and Optimization

Diane Hibbs, Julie Hollberg

In this chapter, you will learn how to

• Understand the success factors necessary for effective governance, including executive buy-in, integration with existing governance structure, and multidisciplinary participation

• Describe the migration from paper processes or an existing electronic health record (EHR) to a new EHR system including organizational strategy, planning, decision-making techniques, training, and implementation strategies

• Document and support downtime procedures

• Propose strategies to minimize major barriers to adoption of EHRs

• Track issues and resolve problems while simultaneously providing high-level customer service

• Assist with verifying that the expected benefits are achieved (e.g., return on investment, benchmark, and user satisfaction)

With the passage of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA), which included the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health (HITECH) legislation, implementations of electronic health record (EHR) systems have increased dramatically over the past five years.1 While some health systems or physician offices are implementing an entirely new EHR system to replace paper-based processes, many others with existing EHR implementations are now focusing on creating more integration across venues throughout a health system or on implementing new functionality to optimize current workflows. Alternatively, a growing number of organizations are transitioning from one EHR system to a completely different one in order to facilitate organizational and technical integration, or perhaps as the result of acquiring new practices and/or hospitals, or simply due to dissatisfaction with their current EHR system.

Combined, we have many years of experience working in complex acute and ambulatory healthcare systems. Our respective organizations, Banner Health (Dr. Hibbs) and Emory Healthcare (Dr. Hollberg), have been using EHRs for over a decade and both recently underwent optimization and replacement projects. This chapter will reference the experiences of these two health systems to illustrate the core concepts and necessary ingredients for successful EHR implementations, incorporating numerous examples and lessons learned throughout the chapter.

Banner Health implemented a new ambulatory EHR as an expansion of its current inpatient system to ensure that patients would have a unified EHR reflecting both inpatient and outpatient encounters. Emory Healthcare began its EHR implementation journey over 20 years ago and has had a unified inpatient and outpatient medical record since 1999; however, the ambulatory clinics were still using paper for all billing and for all orders except prescriptions prior to its optimization project in 2015.

Both Banner Health and Emory Healthcare, coincidentally, have been using Cerner Corporation’s EHR product for many years and are currently using that product in new ways to help in their healthcare optimization efforts. Cerner’s EHR product has achieved Certified Electronic Health Record Technology (CEHRT) designation and is one of the leading EHR systems as defined by U.S. market share, but there are many other EHR products that have the CEHRT designation as well as substantial market share. You are encouraged to learn about the many CEHRT products that can be found on www.healthit.gov web pages that provide more information on the ONC Health IT Certification Program. The many different EHR and HIT products from different vendors provide a rich variety of choices for today’s diverse mix of healthcare organizations.

Using HIT and EHRs for Organizational Transformation

This section will introduce the strategic initiatives Banner Health and Emory Healthcare implemented using HIT and EHRs to improve and transform their organizations. Throughout the rest of the chapter, specific examples detailing the use of HITs and EHRs in these organizations will be given. Governance of and change management approaches for large HIT and EHR initiatives, again using Banner Health and Emory Healthcare as examples, will be covered as well. The principles and practices discussed here can be adjusted as needed and allied to other large HIT and EHR initiatives.

Banner Health

Banner Health is a large health system that spans seven states, primarily in the western United States, and is composed of 29 acute care facilities ranging from critical access hospitals to university medical centers. Banner Health has more than 200 ambulatory clinics and employs over 1,500 physicians, with thousands of additional independent physicians practicing in their facilities. These numbers change frequently as more clinics and facilities are either acquired or built.

The acute care facilities implemented Cerner EHR (PowerChart) in two phases:

• Implementation of computerized provider order entry (CPOE) began in 2005

• Implementation of the physician documentation solution began in 2009

Prior to 2015, the Banner Health ambulatory clinics were using at least six different documentation/ordering methods, including some clinics that were still using a paper system, and none of the clinics using an EHR system were using the same EHR system used in Banner Health acute facilities. As a result, patients lacked a unified medical record and clinicians had to refer to two or more sources of information for their patients and do a lot of manual work—signing in to multiple systems, printing, copying, faxing, and scanning—to find important clinical information and ensure that it was available in each venue for critical clinical decisions.

Banner’s Strategic Initiative

Banner’s project scope statement, an internal document, for this initiative connected the implementations’ objectives to the mission of the organization with the following statement:

Banner Health is committed to providing seamless, integrated care to our patients, and to accomplish this goal, it is imperative that a patient’s complete medical records are readily accessible wherever in the Banner system a patient visits—any Banner Health Center or Clinic or Banner Medical Center.

Replacement of the non-Cerner ambulatory EHR systems with PowerChart Ambulatory occurred in waves, roughly based on geography but with consideration for the number of providers and the different specialties in each wave. The first wave started in June 2015 and the majority of the ambulatory providers had transitioned by the end of 2016.

Emory Healthcare

Emory Healthcare is the largest, most comprehensive health system in Georgia and attracts patients from throughout the southeastern United States. It is the healthcare arm of Emory University, and many of the Emory School of Medicine faculty practice within Emory Healthcare facilities and clinics. Included in the system are six acute care hospitals, more than 100 clinic locations, and nearly 2,000 providers (attending physicians, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants). The Emory Clinic refers to the faculty practice and completed more than 3 million outpatient visits last year. For both the inpatient and the ambulatory settings, prior to 2015, the EHR had rich functionality for nursing, radiology, lab, and pharmacy. All of those clinical areas were documenting electronically and the care teams were able to review results from each of those areas (e.g., view the medication administration record and medication list, lab result flowsheets, and radiology results flowsheets). However, the experience for CPOE was very different between the inpatient and outpatient environments.

While the six acute care hospitals had been using CPOE since 2009, the ambulatory clinics all used paper for billing and ordering (except prescriptions). Consequently, the providers performed a lot of duplicative documentation because orders for referrals, lab, radiology, and other diagnostic tests all required different pieces of paper and each required diagnosis documentation. After completing the orders, the provider also had to transcribe the diagnosis onto the paper billing form. While Emory Healthcare had developed a robust EHR over time (see Table 20-1 for a timeline), the physicians, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants were limited to a generic view of the chart based solely on their venue—inpatient, outpatient, or emergency room. Data needed to deliver care in each specific specialty were not readily available, which decreased efficiency. Summing up the set of issues Emory outpatient providers faced succinctly, a urologist said, “I don’t really care about the vaccinations…I need the med list, my past office notes, any cystoscopies, CT of the abdomen and pelvis to all be face up so that I don’t have to click around so much to find the data.”

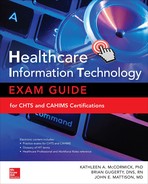

Table 20-1 Emory Healthcare Electronic Health Record Development/Implementation Timeline

In addition to the less than optimal provider documentation support from the EHR, the Emory Clinic was facing the looming transition from ICD-9 to ICD-10, which had the greatest impact on medical coders but also impacted providers and clinicians, and frustration among physicians was still high as a result of the additional work necessitated by the HITECH meaningful use requirements. Executive leadership was concerned that the decreased efficiency resulting from the extra time required to find a specific ICD-10 code would further frustrate physicians and that a proposed workaround using paper billing with a limited set of the most commonly used ICD-10 codes was unsustainable.

Based on feedback from the broader organization, executive leadership realized that overall provider satisfaction could be improved and workflow made more efficient by further optimizing the Emory EHR, and as a result Emory undertook a significant optimization project in 2015. This project was known as “Provider Workflow Optimization.” Each clinical division or department created their own workflow EHR view, which included the specific clinical data that they wanted readily available, as well as a quick orders page, similar to a superbill that many providers were familiar with. This quick orders page included their specialty’s most commonly used orders and billing codes. The project had a very aggressive timeline, largely due to the ICD-10 transition deadline. Emory successfully completed 37 go-lives in just five months. Technically, each go-live required creating a new specialty position within the EHR and two new workflow pages. Operationally, each go-live required implementation of changes for all of the practice sites for that specialty. Emory had just over 100 geographically distinct ambulatory practice locations.

Emory’s Strategic Initiative

The goals of the Provider Workflow Optimization project were to to leverage HIT to make it easier to deliver high-quality healthcare and to improve the patient and the provider experience. To operationalize those goals, project objectives such as bringing the right data to the right provider at the right time and facilitating the transition to ICD-10 were identified and helped to guide the project.

Governance of Large HIT and EHR Initiatives

Effective governance is essential to the success of any healthcare IT implementation project. Key characteristics of effective governance HIT implementation include2

• It is inclusive of and accountable to all relevant stakeholders.

• Governance and guiding principles are based on the organization’s mission and those principles are incorporated into the work of the team.

• It strives for transparency to all constituents to assure decisions are fair and equitable for all parties involved.

• The team leaders utilize online collaboration tools (e.g., Google documents, SharePoint, Box) to facilitate optimal involvement in the discussion and dissemination of the decision-making process and the knowledge coming from the organization and governance teams.

• It is responsive and highly communicative within the organization.

Executive Leadership

Every successful company spends a considerable amount of time identifying, planning for, and then achieving its corporate initiatives each year in all areas of its business. For a hospital or healthcare system, these initiatives may be financial, regulatory, and/or clinical. Implementation of an EHR extends into all these areas, as outlined in Table 20-2.

Table 20-2 Potential EHR Implementation/Optimization Impacts of Healthcare Organization Initiatives

Successful implementation and, more importantly, subsequent adoption of a new EHR requires corporate initiatives to be translated into “What’s in it for me?” (WIIFM) for the clinical staff, especially physicians. Executive leadership must be willing and able to recognize and remove barriers encountered by the implementation teams.

Leveraging Existing Governance Structure

Healthcare organizations have a complex hierarchy of committees, councils, and boards. Adding EHR discussions to regularly scheduled meetings of these entities is preferable (when possible) because it minimizes the difficulty of organizing more meetings and avoids repetitive discussions. However, the breadth and pace of an EHR implementation will likely require creating specific separate meetings to ensure effective, broad decision making. When asked to describe their governance structure, many hospitals and ambulatory clinics can produce impressive organizational charts and documents. However, effective governance is more than a simple list of committees and representatives.

Multidisciplinary Participation

Healthcare requires an entire clinical care team—doctors, nurses, medical assistants, pharmacists, radiology and lab personnel, dieticians, physical therapists, and many others—collaborating and relying on each other to perform their work. Beyond the clinical care, healthcare operations require an even broader team including reception and scheduling staff, billing experts, coders, IT staff, compliance and privacy officers, and medical records personnel. The scope of a project determines who needs to participate on the various governance committees, and all stakeholders should be represented at the appropriate level of governance within the project.

A steering committee will likely have oversight of the project. This committee may be composed of executive leadership, IT leadership, and clinical leadership, and may have vendor stakeholders as well. This committee will meet less frequently and will review updates from the various teams that report to it.

A project team will meet very frequently. This team will be led by a project manager and will have heavy participation from both the vendor and the healthcare organization side. This team will hash out the details of the implementation. It is imperative to have a strong and effective project manager leading this team, one who isn’t afraid to ask the hard questions and hold people accountable for their responsibilities.

While it seems intuitive that the right stakeholders should participate in the right meetings, it tends to be easy to forward all the meeting invitations to more and more people, and generally the more people in a meeting, the harder it is to make a decision. Try to invite only the necessary people to participate in each meeting. By the same token, be sure the attendees include the people who can move the project forward. An important lesson learned at Banner was that meetings lasting longer than 30 minutes rarely included the required decision-maker. As a result, the next question was usually “Who needs to be invited to the next meeting to get this decision made?” Banner learned that involving too many people in meetings often resulted in wasted time because no decision was actually made.

Clinical Stakeholders

It is imperative to have clinical leadership involved from the beginning, even before the initial decision is made as to which system will be implemented. This clinical buy-in will prove invaluable in the change management process and in identifying and communicating the importance of the changes. The best clinical representatives are known for their clinical expertise, are influential, and are highly regarded by their peers. Consider specialty-specific leaders who will have relevant and meaningful input regarding content, workflows, and the order sets they and their peers will use.

Banner’s Governance

Clinical care at Banner is managed as a system and is therefore very standardized. The Care Management Council, led by the system-wide chief medical officer (CMO), is composed of Clinical Consensus Groups (CCGs) for each specialty. These groups include representatives from each facility and all the pertinent disciplines—physicians, nurses, pharmacy representatives, and so on. These CCGs create evidence-based Clinical Practices that define the standard of care and drive the policies and procedures for the entire health system.

The strategic initiative guiding the ambulatory EHR implementation at Banner was developed by the senior leadership team and was led by the chief medical informatics officer (CMIO). These corporate stakeholders were joined by clinical stakeholders from the various CCGs to form the needed governance for this implementation. The importance of this governance structure is that it was clinically driven, rather than IT-focused.

Emory’s Governance

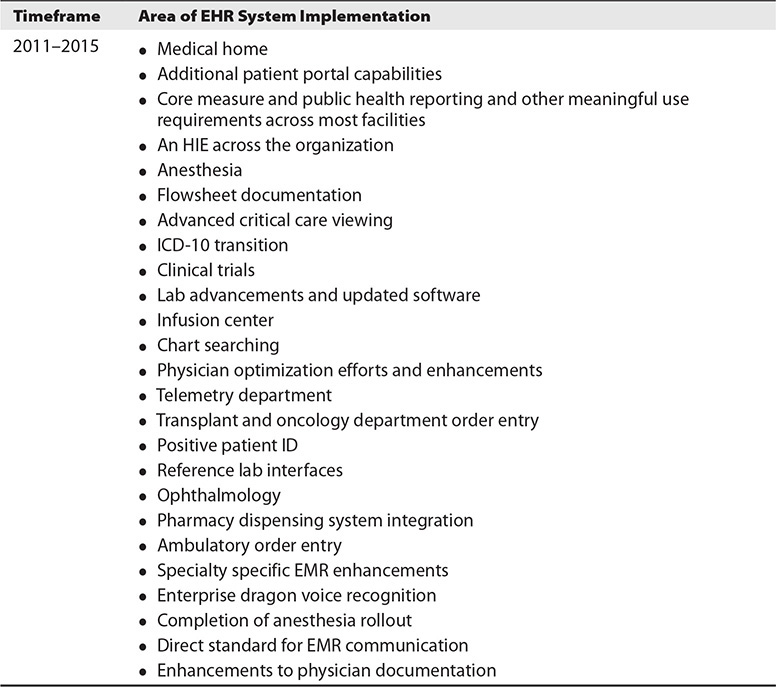

The operational sponsors of the project involved senior leaders within Emory Healthcare and included the CMIO, the CMO of the Emory Clinic, and the director of revenue cycle. Each week, they met for 3–4 hours with the leaders of the four teams that were very hands-on with each of the clinical sections. See Figure 20-1. The operational sponsors presented to the executive sponsors for one hour every other week throughout the project. This level of hands-on leadership was essential to remove barriers and make decisions so that the project could stay on schedule.

Figure 20-1 Project leadership team for Emory Provider Workflow Optimization project

Each clinical division or department was required to identify at least one physician leader for the entire optimization project. The physician leader was partnered with an administrator and clinical operations manager as well and these triads were responsible for designing the new workflows and for being available during the go-live to make any workflow decisions that had not been addressed during the project planning.

Change Management

An EHR implementation can involve one physician’s office or an entire multihospital health system. As described in this chapter, it can involve state-wide or multistate groups of providers. In all these cases, change management is a critical component. Chapter 10 describes a multilevel change management process that can be applied to EHR and other HIT implementations and is consistent with the implementation principles and practices in this chapter. To the process described in Chapter 10, we add the following:

• People handle introduction of innovations or technology differently.

• It is essential to identify WIIFM for the end users from the very beginning.

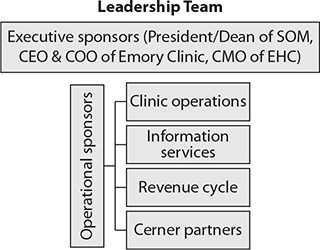

Everett Rogers’ theory of diffusion of innovations is a common theory that change managers have applied to many areas, from farmers’ views on soil conservation to mass marketing advertisements and much more.3 It is likewise a very useful theory to help EHR and HIT implementers understand and deal with the different types of responses people have to large-scale technological change. The theory identifies classes of adopters of a message, belief, or technology: innovators, early adopters, early majority, late majority, and laggards. Figure 20-2 presents alternative names for these classes that may resonate in modern organizations more. Whatever the names associated with the types of adopters, the important concept is that in a large organization, adoption of a new technology varies significantly across individuals. This has many implications for governance, stakeholder buy-in, communication about the initiative, end-user training, and more.

Figure 20-2 Product adoption curve

Physicians are typically motivated by the opportunity to improve patient care or to save time, or both. Understanding and leveraging the WIIFM perspective for physicians helps immensely throughout the implementation of EHRs. Despite the perception of frequently objecting to or complaining about things that change their workflows, clinicians ultimately care about their patients and about delivering high-quality care. Tapping into these values can help articulate the WIIFM. Examples include

• As a physician, have you ever had a patient who had previously been treated in your hospital, whose old records would have been very helpful in your decision making but could not be located by the medical records department?

• How many times have you consulted another physician for help on your patient but the dictated report from the consulting physician was not available to you for several hours or days?

• How many hours have you spent in the medical records department with a stack of charts that needed your signature?

• As a physician, have you ever received a phone call from a hospital regarding your patient while you were in your office or at home and you had to rely on someone else to look at the chart and decipher the handwritten notes and orders already on the chart?

• Have you ever mistakenly prescribed two drugs that interacted with each other because you didn’t realize they interacted?

These are salient examples of things that matter to practicing physicians, and if you can help them see how patient care will improve through the use of an EHR system, they will be much more likely to not just accept the new EHR but to truly adopt it.

Managing the Project

So far this chapter has covered the high-level concepts and keys to a successful EHR selection and implementation. Ultimately, as with any successful project, the details are critical. Healthcare organizations have widely adopted and adapted the practices and principles of the discipline of project management of large HIT initiatives. The project manager leads the teams and manages all the tasks and timelines. It is imperative that the project manager create and maintain a master document that lists all the tasks, who is responsible for completion of each task, when each task is scheduled to be completed and is actually completed, and any dependencies for completing the work. See Chapter 10 for much more information on project management practice and principles that can be applied to EHR implementations and optimizations. What follows are a few of the more important details every EHR implementation project should include as part of the project plan.

A Good Product and Team

It is assumed in this chapter that the EHR solution has already been carefully vetted and chosen. As part of the selection process, the organization responsible for implementation should also be identified. A very knowledgeable team that understands the specific system being implemented and how to localize and optimize it for your organization is invaluable to your success. As you begin discussions about design, setting preferences and privileges for the users, and developing specific workflows, the downstream effects of those decisions may not be readily apparent. Including in those discussions either vendor representatives/consultants or knowledgeable third-party consultants as a partner, with their considerable experience from similar implementations at other sites, is imperative. These team members will know the vendor’s core recommendations as well as other best practices you might need to consider. They will know the effects of each decision on downstream applications across roles and venues, especially if these recommendations are not heeded. A caveat when leveraging third-party implementation resources is that you should ensure they have current knowledge and recent experience with the specific EHR system, as systems are constantly changing with new functionality and changes to existing capabilities.

Some organizations think it will be less expensive if they do all the design, build, and implementation themselves in an effort to save money. However, when the cost of the time and resources required to “figure it out” on your own is factored in, it very well might be less costly to use expert external resources for this purpose.

Banner Health partnered with Cerner Corporation to implement Cerner’s EHR solutions in the ambulatory clinics. This was a multiyear, strategic partnership, with many Cerner associates actually relocating and permanently working within the walls of Banner every day of the project in the Alignment Office (while remaining employees of Cerner). They became members of the Banner implementation team and their role was to ensure successful implementations, help with adoption of new technology, and foster new ideas and innovations.4

Emory Healthcare lacked the technical bench strength needed to customize, build out, and test all of the new desired EHR functionality, so it also partnered with Cerner. The internal Emory application experts, who were either experts on clinical workflow themselves or who had experience working with Emory subject matter experts, gathered all of the requirements and then leveraged a large Cerner team to complete the technical build.

The Orders Catalog and Order Sets

Physician and provider orders have been and continue to be a central and far-reaching function in hospitals and other types of healthcare delivery organizations. Their orders initiate a cascade of activities that, in aggregate, impact every department and area of a healthcare organization as well as some external clinical or business entities such as pharmacies and laboratories not owned by the healthcare organization. Order catalogs are organized collections of all of the “orderable” diagnostic or therapeutic treatments and/or services that a provider can choose from that they wish their patient to receive. Order sets are a collection of two or more individual orders that are often organized around a transition of care. Examples are a hospital admission order set or an ambulatory physical therapy order set. Order sets are also organized around conditions, such as community acquired pneumonia or a well child provider visit.

Prior to the existence of EHR systems, physicians wrote out each of the tasks they wanted performed on paper order sheets that looked very similar to notebook paper. In this “paper ordering paradigm” the order written by Physician A may not have been the same as the order written by Physician B for the same task. For example, a diet order from Physician A may read “Regular diet” while Physician B enters “House diet.” Order entry modules of hospital information systems (HISs), a precursor to EHRs, enabled a nursing unit clerk to interpret a physician’s paper order and either key it into the HIS or use pull-down menus in the HIS to select the desired order. Errors cropped up in this semi-automated approach due to non–provider order entry staff misinterpreting providers’ handwriting or entering an order that best fit what the entry staff member thought the physician wanted.

To deal with this, over the past ten years, most healthcare systems have widely adopted the computerized provider order entry (CPOE). CPOE is a clinical information system, these days usually a module of an EHR, that allows clinicians to record patient-specific orders (tests, treatments, management plans, and the like) for communication to other patient care team members and to other information systems. A challenge with CPOE is standardizing all these various orders and communicating to end users how these orders will be searchable in the new EHR system. One solution is to have order aliases that all point to the same order; for example, ordering a “CBC” or ordering a “Complete Blood Count” would both show up in the lab as the same order.

For new EHR implementations from paper, an order catalog will need to be created that includes all the orders that all the physicians will ever want to write—certainly no small task. On the other hand, if your implementation is a conversion from one EHR system to another, this will be a good time to review available orders from the existing legacy EHR order catalog and remove outdated ones. In either case, this task will require significant time and resources to complete.

Creating order sets will ease CPOE as well as drive standardized practices. These standard order sets should be developed by the departments who will be using them, with added input from ancillary service lines (e.g., lab, pharmacy, radiology, etc.). A great example of this is in the use of chemotherapy order sets by oncologists. These highly specialized, evidence-based order sets are very detailed and prescriptive, with certain drugs being given on certain days and labs being drawn at defined intervals. These order sets, and most other types of order sets, if implemented well, can reduce the chance of human error. Other good examples of order sets are those used for clinical emergencies (e.g., codes). Using order sets in these cases eliminates having to remember and then laboriously search for individual orders when time is especially critical. Additionally, as organizations shift from fee-for-service care to value-based care, electronic order sets or quick orders pages are a way to make it easier for clinicians to practice evidence-based medicine.

Documentation Templates and Note Hierarchy

Similar to standardized order sets, clinical documentation standards can be encouraged with the use of templates. Clinical stakeholders, representatives from the healthcare information management (HIM)/medical coding, and billing personnel all should participate in the development of these templates. Templates may be different for each specialty and for each venue; for example, an obstetrical office note is much different than an inpatient cardiology note. These templates can be created to include any required fields to ensure compliance with regulatory measures or health system standards. Caution should be used with required fields, however, as the trigger used to identify a required field as such (highlighting, asterisks, etc.) may inadvertently guide the provider to only fill in the required fields and skip over other important fields.

In addition, the HIM department should be included when developing a standard approach to the note hierarchy or filing structure within the electronic record. This ensures clinical documentation is easy to navigate and key information can be quickly located when needed.

Migrating Data

Any patient seen in a clinic or within an acute facility that is part of the healthcare organization implementing a new EHR system has data in some system prior to the current implementation, whether that is another EHR or even a paper chart. The usual assumption of clinicians is that all data from all dates should be migrated from the old system into the new one and be easily accessible moving forward. Unfortunately, this is not realistic and the focus will need to shift to determining which data are most needed and how that data will be translated. In many cases, it is a better decision to actually enter new data when the patient is next seen for care (i.e., as if the patient were new instead of an existing patient). This will mitigate the problem of a data mismatch where the data in one system’s database is not a one-to-one match for the new system’s database. Data migration, in any form, will require considerable time and resources to accomplish.

If the EHR implementation is taking place in the acute setting, it is imperative to have recent (from the current encounter) clinical information at least available for review either as a printed report or as read-only information in the legacy system. Ideally, that clinical information will be migrated to the new system just prior to conversion in order to provide seamless patient care. Conversely, in the ambulatory setting, this migrated information is nice to have but is less urgent, especially if it will remain available for review within the old system. Old information becomes most valuable when it is available in the expected locations in the new system (e.g., the patient’s home medication list appears in the Home Medications section of the EHR). This may require manual data entry to accomplish the most seamless and accurate results. In the ambulatory setting, if the quality of the existing data is suspect or if challenges are expected with migrating data from one electronic system to another, it is helpful prior to the patient visit to have a team member reference the previous record and manually enter a minimal set of data including the problem list, medication list, and allergies. Consideration must be given to how long historical data that are not migrated will be available for review in a legacy system, and this will likely be determined by the cost of maintaining that system.

Extraction, then Conversion

To migrate data from an old system to a new one, the data must be extracted from the old system and then, depending on the format of that data, converted into a format that the new system can handle. As described previously, some data may actually be more accurate if reentered as new data, though that decision may be met with some opposition from providers. There is a cost both in time and money when data must be entered manually. Migrating allergy data is a good example. If the designation of an allergy extracted from the old system does not match a discrete data element in the new system or was even entered as free text, it will be migrated inaccurately or not at all, leading the provider to see the wrong information in the new system. At Banner, to ensure allergy data were migrated accurately, the Physician Informatics team manually matched thousands of allergies on a spreadsheet of data extracted from existing ambulatory systems to their corresponding data elements in the Cerner EHR system.

Some organizations know the data quality is unreliable and instruct clinicians to “clean up” core lists, such as patient problem and patient medication lists, post-conversion. The other option is to have staff or physicians edit/update existing core lists prior to conversion. Both approaches can be effective but each has its pros and cons.

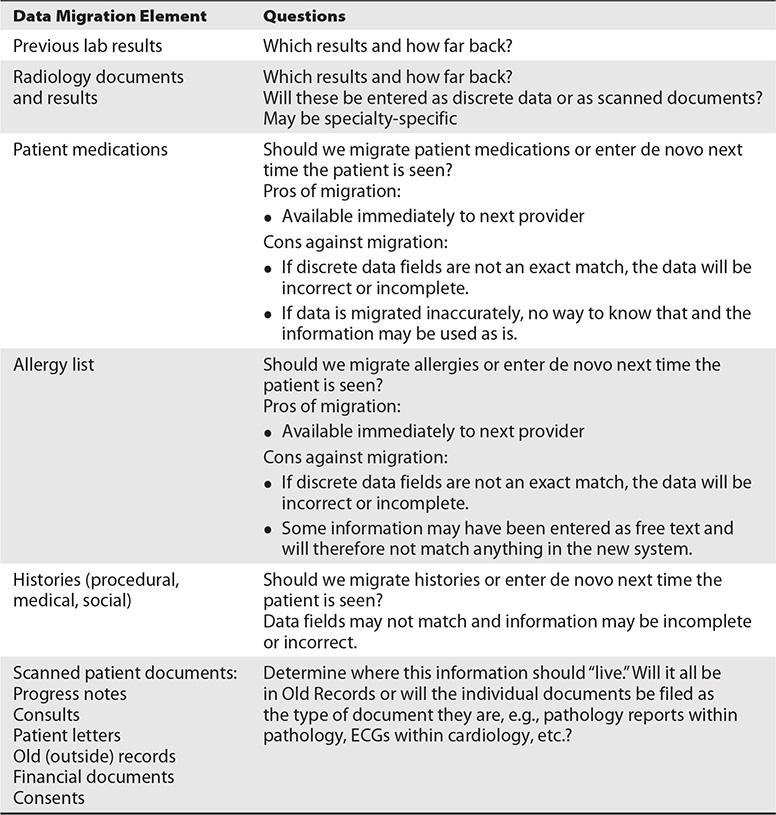

An excellent checklist resource for data migration is provided on the HealthIT.gov web site.5 Table 20-3 shows sample questions to ask and consider.

Table 20-3 Questions to Consider for Data Migration During EHR Implementations

Develop Workflows

The clinical leaders should develop workflows appropriate to their specialty and clinical need. At a minimum, the following workflows should be addressed:

Ambulatory:

• New patient visit

• Established patient visit

• Sick (or problem-focused) patient

• Between-visit phone calls

• Prescription refill requests

Acute:

• Patient requiring admission from clinic

• Daily management of hospitalized patient

• Transfers within or between facilities; e.g., medical unit to critical care or to and from surgery

• Handoffs between clinical care teams

• Medication reconciliation (reviewing medication list accuracy on admission and discharge)

• Discharge from hospital, including to home or to some type of transitional care

Emergency Department (ED):

• ED visit only

• ED visit with admission to hospital

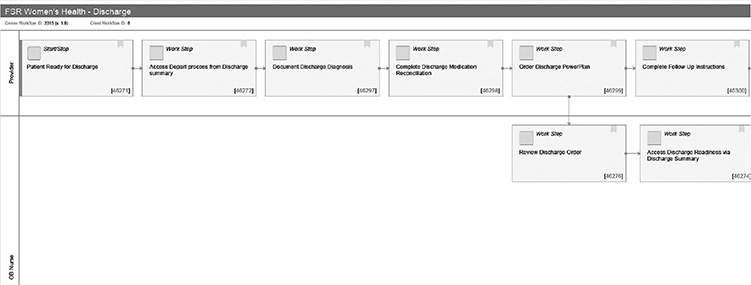

These workflows should include all roles and should clearly identify the tasks within the workflow for which each role is responsible. Representation in the development of these workflows from all disciplines (including nursing, physician, pharmacy, radiology, etc.) will ensure that the workflows have been thoroughly evaluated from the perspective of all those affected. Each workflow should be documented and approved by the clinical stakeholders, and any changes should go back to these stakeholders for governance through the accepted change process. Figure 20-3 is a graphic representation of a “Discharge from Women’s Health” workflow. It is an example of the steps required of a provider and a nurse to efficiently and effectively discharge a Women’s Health patient from a clinical setting. Note the separation of responsibilities by role into “swim lanes.” For more information on process and workflow management, see Chapter 10.

Figure 20-3 Example workflow diagram depicting a patient discharge from a clinical setting

Policies Affect Workflows

Consider the policies you either currently have in place or plan to implement, and how they will affect your new EHR. How do those policies fit into current workflows and how might they be different with new electronic workflows? For example, medication reconciliation is required by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) for meaningful use compliance.6 Most, if not all, organizations have a policy requiring physicians to perform a medication reconciliation (i.e., review and make decisions regarding the patient’s current medications—continue or stop them—at each encounter for care). However, compliance with the policy following the implementation of a new EHR requires developing a workflow that is easy and makes sense to the provider who is expected to perform it. Too often these policies are created by a group of administrators who may not ever use the EHR at all and may inadvertently create an unrealistic workflow for the busy provider. Providers will then either neglect to perform the task at all or create a cumbersome workaround that is unlikely to be successfully performed on each patient, and thus the policy is not followed. Having providers involved in the development of the expected workflow will help to ensure the highest chance for success, and this workflow can then be considered when writing or rewriting the policy.

Another common example of conflict between policy and workflow occurs with CPOE. CPOE is also mandated by CMS and is a part of most organizations’ policies. The easier it is for providers to enter their own orders in the EHR, the higher the CPOE rates will be. In examining why an organization is falling short of their goal for CPOE (or any other metric), it is imperative to carefully scrutinize both the current workflow and the expected workflow and determine where the opportunities exist to streamline and improve. If the expectation is 100 percent provider entry of orders through CPOE, access must be available on multiple platforms. In addition to the standard PC workstations on the hospital units or within clinics, this access must include laptops and mobile devices and should allow VPN access as well. Attention must be given to how those various platforms accommodate the workflows. It is unrealistic to require 100 percent CPOE if your providers are not physically inside the hospital and have no other way to enter the orders. Consideration for these realistic situations when writing a CPOE policy, and other similar “new system” policy, is imperative.

Verbal and telephone orders are two situations which require additional consideration and planning. In general, physicians are asked and expected to enter all orders in the EHR themselves. This policy often places nurses in a precarious situation when physicians ignore or don’t follow policy. When a physician attempts to give a verbal order (assuming the physician is also capable of personally entering the order), following the policy means the nurse would potentially have to refuse to carry out the (verbal) order of the physician, thereby putting the patient at risk. While this is extreme, it illustrates the need to consider EHR workflow when writing and amending policies.

Testing

Every part of the EHR build will need to be tested to ensure that the expected responses are achieved. This will require many hours and multidisciplinary resources. For instance, when an admission order set is created, it will need to be validated by the clinical stakeholders to ensure that all the intended orders have been included. The pharmacy stakeholders will need to ensure that the medication orders actually reach the pharmacy when they’ve been placed, as do radiology, laboratory, dietary, and every other affected department with their departments’ respective orders. Similarly, when an order is placed for periodic vital signs, a nurse should actually be notified in a reliable fashion of this recurring task. and if the process is working as expected. Similar testing will need to be performed for each part of the EHR, including documentation, printing, and so forth.

Another important part of the HIT department’s work, at least as important as functionality testing, is usability testing. In other words, can the user perform the tasks as expected? Step-by-step, realistic clinical scenarios should be written and available for testers to walk through. Ideally, end users will be able to test these workflows prior to go-live to ensure things do indeed work as expected. Engaging end users in this testing will have the added benefit of allowing them to become more comfortable with the change prior to go-live.

Training

We will give you some practical guidance on EHR implementation training here that is meant to complement the more formal and comprehensive EHR and HIT training information in Chapter 21.

We recommend making baseline training mandatory and requiring that it be completed before access is granted to the EHR. While the training venues and platforms will vary—e.g., classroom, web-based training, 1:1 coaching—most clinicians, even technically savvy ones, will not be able to effectively learn how to use a new EHR while simultaneously trying to continue delivering patient care at their normal pace. Most people can relate to having bought a new high-end computer, stereo, or automobile with a number of options only to become frustrated with minimal or no training and ultimately end up discovering and using only a small percentage of the capabilities.

Mandatory EHR training is easier to achieve for employed physicians than for independent practicing physicians, especially those who practice in your facilities only sporadically. Some specialists practice at several hospitals in a given community and may only see a handful of patients at one hospital in a given month. Making training a requirement to maintain privileges is one procedural way to achieve this goal. Appealing to a physician’s desire to maintain patient safety and deliver care as efficiently as possible can also be persuasive and lead to longer-term acceptance and success. Having the message and requirements communicated by clinical leadership rather than primarily by the technology leadership is crucial. As with other clinical skills, having end users trained appropriately is essential to a successful implementation. Additionally, some level of competence should be demonstrated either in one-on-one sessions or in a skills assessment following training.

Traditional training has often been focused on functionality rather than on the providers’ workflows. (One example of a provider’s workflow in this context is the way a provider works and the process steps the provider takes during a visit with the patient and clinic staff.) In contrast, training to a workflow will provide much more of a realistic framework for the end user to truly get a feel for the way the new system will function in practice; for example, the physician is trained on how to use the EHR from admission to discharge instead of only being taught how to enter an order or how to write a progress note. Determine the one best way to perform the workflow, even if there are many other ways, and then train to that workflow. It is important not to try to teach every possible nuance in a single training session. After learning and using the “basics” for some period of time, those users who would like additional training can learn the advanced “tricks” of the system and become even more proficient and efficient.

Reduce Schedules for Go-Live

During and after go-live, giving physicians time to learn while caring for patients requires that they reduce their schedules to some degree. There is considerable debate and no real consensus about the ideal amount of reduction and timeframe required, and determining this will depend upon the extent of the change as well as the specialty.

Banner reduced schedules by 25 percent for two weeks before go-live and by 50 percent for the two weeks following. The time prior to go-live was used to set up preferences, create “favorites” or commonly used orders and document templates, and increase familiarity with the system. The reduction of schedules for two weeks after go-live afforded the providers time to develop their workflows and learn to complete the work in real time without excessive delays in patient care. The schedule was then increased to 75 percent the third and fourth weeks and was back to 100 percent by week five.

Since Emory Health did not compensate physicians for the lost revenue had they all chosen to reduce schedules, actually taking the step of reducing schedules was left to the discretion of each clinical service line or specialty. Individual specialties approached this differently, from blocking 20 percent of appointments to restricting double bookings in specialties with high rates of no-shows. Furthermore, some Emory clinical service lines or specialties also scheduled all appointments as new patient appointments (typically longer appointments than for returning patients) for a period of time to allow more computer time per patient.

While the financial impact on the organization can be significant, and these examples of schedule reduction may seem excessive and unnecessary to some, there are many challenges that only become apparent with the go-live. Reducing schedules will give providers a chance to become proficient with the new system without sacrificing patient satisfaction. Reducing schedules can minimize the stress of transitioning to a new EHR and also learning while using the system.

Ambulatory implementations present unique challenges where physicians are the rate-limiting step in patient throughput. For many physicians, the transition from paper to an electronic record or from one electronic record to another is very disruptive. Ideally, the electronic work will be performed in real time during patient care, but that can be overwhelming when there are five patients waiting to be seen and the provider is trying to place an order but can’t figure out how. It is important to communicate to providers that the way they practice medicine is not changing, only how they document that care and place orders. Some organizations take a “big bang” approach, implementing all the system’s capabilities, and then expect physicians to adopt all of the new tools at once. Others find that a gradual approach is more tenable. For example, providers who traditionally dictate their notes could alternate between using traditional transcription and using the new documentation system on the first day and by the end of the week transition completely to the new documentation system. In an effort to minimize the negative impact on revenue during the implementation, giving providers some kind of “credit” for the patients they would have normally seen may be helpful in gaining buy-in and increasing their engagement.

It is important to realize that some providers will want to return to their normal routine faster than the prescribed schedule. However, an alternative for these providers would be to have them assist some of the other providers during the free times they have during reduced schedules. This approach fosters esprit de corps and helps the whole clinic return to a normal level of productivity faster. Also important to remember in the clinic setting is that associates in registration, billing, and scheduling and medical assistants also see dramatic changes in how they do their work, and their efficiency directly impacts the physician. Until they become fully proficient, physicians can expect their productivity to also be impacted.

Downtime Procedures

Ironically, as much as clinicians complain about having to shift their paper processes to electronic ones, over several months they become dependent upon the electronic system and rapidly forget how they used to function without it. Unfortunately, no system is fool-proof. There will be times when the system is unavailable for some or all of its functions. Downtimes may be scheduled or unscheduled and may include situations such as a temporary loss of network connectivity, malfunction of interfaces, or even scheduled time to perform system upgrades. Downtimes are inevitable and preparing for them is an essential part of any implementation. This preparation is often neglected in the midst of focusing on the go-live.

Downtime preparation post-EHR implementation requires the entire multidisciplinary team to plan for how they can deliver patient care in the absence of the EHR. The length of the downtime may also affect the processes that are developed and, to the extent the downtime can be estimated initially, which procedures should be implemented. For example, Emory hospital nurses document vital signs on paper for downtimes greater than two hours and that documentation is then scanned into the medical record after the patients’ discharge. Only the medication administration record (MAR) is retrospectively updated after a prolonged downtime.

Being prepared for downtimes is more than merely keeping all of the old paper forms and processes. For example, Emory’s transition from paper billing to electronic billing coincided with the transition to ICD-10. Emory had not created ICD-10-compliant paper encounter forms, so preparing for downtime post-optimization required the revenue cycle team to work with each clinical group to develop new backup processes.

After an organization has created its processes and downtime forms, a thoughtful communication plan must be developed, especially for large systems that have clinics spread geographically and/or hospitals with multiple units. Options to consider include

• Having a system-wide paging list

• Phone trees

• A process for e-mail notification

• Alerts when signing into the system (if the system is still partially functioning)

While creating the communication plan initially can be a lot of work, it is also imperative to review the list of personnel, phone numbers, and clinic locations quarterly since healthcare is an ever-changing business.

Go-Live Support

Using a new system while simultaneously trying to deliver patient care at the same pace is challenging. Earlier in this chapter, we discussed the importance of reducing the clinicians’ schedules, if feasible, to enable them to begin using the new EHR without becoming frustrated and prolonging patient wait times. Another way of minimizing the pain of adoption is at-the-elbow support, which may be accomplished by using adoption coaches at go-live and by having plenty of superusers trained and available. Superusers typically work for the organization that is implementing the new system or functionality and receive additional training beyond what is required for the typical user. Adoption coaches also receive additional training, are often employed by a third-party vendor or consulting firm, and may focus on a subset of users, such as physicians.

Regardless of how fabulous or thorough training classes are, adult learners often need hands-on experience using the actual system in order to absorb the material. Many physicians only start asking more advanced questions once they are using the new EHR to provide patient care. A frequent observation is that physicians want help in the exact moment that they need it—not ten minutes before, not ten minutes after—and the implementation team’s ability to accurately predict those moments is close to zero. One way to tackle that challenge is to locate trainers, adoption coaches, and superusers throughout the clinical areas so that the physician literally has someone at the elbow whenever a question arises. If that is not an option because fewer support staff are available, paging and cell phone notification can expedite their movement. Distinctive clothing is an easy way to identify staff dedicated to supporting physicians or other clinical roles. During the first week of go-live, the ideal ratio of coaches to doctors often is 1:1 or 1:2, but thereafter that ratio can be increased relatively quickly to 1:3 or 1:4. However, we recommend having ongoing coaches either stationed in the clinical setting or rounding throughout multiple clinical settings for at least four weeks after go-live.

In settings where physicians may have diverse responsibilities and are not in the same setting every day, it may be necessary to extend the local support longer. For example, at Emory, many of the faculty have less than three half days of clinic per week, so they required more weeks of at-the-elbow support in order to receive the same net amount of support on the new system. While no organization can afford to maintain trainers and supporters indefinitely, physician adoption, satisfaction, and learning are all higher when their questions can be answered promptly.

Superusers are the next line of support. They may or may not be technologically superior to their peers, but they have a very thorough knowledge base of the system and the expected workflows. Almost more important than their technological skills are their motivation, respect by their peers, and ability to share the vision of the future state. Superusers should be trained ahead of the general users, both on how to technically use the system and on the new processes and workflows. Superusers must understand the new workflows and often are helpful in designing and testing them. Training these people ahead of others will allow your team to hear questions that you may not have considered and to polish the answers. It is also important that the superusers and the training team be on the same page in terms of teaching what the entire implementation team considers the optimal workflow for that specialty. Most EHR systems offer some flexibility in how a specific process can be carried out and the order of steps within a workflow. Superusers should teach the agreed-upon optimal workflow even if they prefer a different, “outside-the-box” way of doing things.

Emory Go-Live Coaches

Emory invested heavily in coaches for go-live. Coaches were available in 1:1 or 1:2 ratios for all physicians, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants for the entire first week of go-live. Support ratios were then increased (e.g., to 1:5 or 1:8) over the next three weeks. Because the project was so large, a coaching leader was designated to work with each of the IT project managers and the local clinical leadership triads to identify which users required additional support (i.e., continuation of 1:1 support) versus those transitioning to only needing answers to occasional questions.

Emory also learned that it was important for the IT or clinical operations manager to intentionally pair a specific coach with a specific physician. When introducing the coach to the physician, we set expectations that the coach was going to stay in close proximity to the physician for the entire clinic session. These introductions were in response to a lesson learned after the first couple of go-lives, during which some physicians told their coach that they would call him or her when needed. That physical distance resulted in the physician not asking as many questions because the coach wasn’t literally at the elbow. It was also very helpful for the superusers to receive 1:1 training with a coach prior to go-live and to practice walking through each of the workflows. This exercise enabled the coaches to learn the practice’s workflows and gave the physician superuser greater confidence, which in turn enhanced that individual’s leadership abilities during go-live.

During and Post Go-Live Communication

During the go-live, frequent communication is imperative, especially if more than one location is going live concurrently. One strategy Banner used was to keep a conference line available for anyone to call into when an issue arose. Banner also held daily status calls that allowed everyone to hear the challenges and the successes from all the sites. These calls included corporate leadership, site leaders, end users, and IT leadership and staff. Plan for daily calls for at least a week and, depending upon the magnitude of change, longer as needed. Additionally, provide a way for end users to make suggestions for improvements and enhancements and develop a system of tracking those requests and the outcomes. As these suggestions come in, it will be necessary to prioritize them according to urgency. Finally, provide transparency as to the status of those requests to encourage everyone to continue to submit them as they encounter opportunities to improve workflow and overall system functionality.

Banner’s system was to prioritize issues and suggestions based on the following:

• Issues that were affecting patient care or had significant financial consequences

• Suggestions that could provide similar results or functionality as the previous system

• Helpful suggestions that were generally good ideas but considered nice-to-have functionality

Emory conducted debrief conference calls at the end of each day during go-live. These calls were facilitated by one of the project’s operational sponsors or an IT director, and a member of the leadership triad from each practice was required to participate to answer three questions for that practice:

• What went well today?

• What didn’t go well today?

• What are you going to do differently tomorrow?

These debriefings enabled all of the clinicians living through the change to connect, empathize, and strategize. Because they had staggered go-lives, they had one call each day for the practices that had gone live that week and another call for any practices that were in their second week or beyond. Each practice site was required to participate for at least two weeks, and as things stabilized, the length of the calls shortened as the focus centered on the ongoing problems and potential solutions.

The issues and suggestions list was collected from people who called into the conference line, from input during the debriefing calls, and from leadership rounds during and after go-live. In total, over 1,300 issues were collected over the two months of go-lives and they ranged from simple requests for access changes to requests for significant enhancements. The issues were categorized based on urgency, clinical specialty, and type of request (e.g., minor change to fix now, future functionality, broken functionality). By the end of the project, 700 issues were resolved and the remaining 600 were analyzed to determine the focus for the next wave of optimization.

Monitoring Success

Keep in mind, a go-live is really just the first day of the next phase in your project. You may have implemented the best of the best systems, but if the people on the front lines are not using that functionality as intended or have developed a number of workarounds, you may have wasted a substantial amount of money. Leveraging usage data from the EHR enables the team to identify users who are struggling and opportunities for improvement across the system. Many of the EHR vendors now offer analytics capabilities that are detailed enough to provide specialty and user-level reports.

Emory Provider Go-Live Metrics

During Emory’s optimization project, ten metrics were monitored:

• Total Time in the EHR per patient (sum of documentation, orders, chart review, and other work in the EHR/patient)

• Documentation time (average amount of time spent using the documentation tools per patient)

• Orders time (average amount of time spent using the ordering tools per patient)

• Chart review time (average amount of time spent using the chart review tools per patient)

• Percent of Transcription (percent of notes completed using traditional transcription)

• Percent of Orders entered electronically versus via paper

• Total number of orders entered electronically

• Percent of Dynamic Documentation (percent of notes completed using Cerner’s newer documentation tool)

• Percent of PowerNote (percent of notes completed with Cerner’s older electronic documentation tool)

• “Pajama time,” or time spent outside normal clinic hours (typically the amount of time in the EHR between 6 p.m.–6 a.m. Monday to Friday plus weekend time)

Emory exported the data into Excel spreadsheets, developed for each specialty, that tracked each of these metrics for all of the attending physicians. Both the mean and the median for the metrics were calculated across each specialty to ensure that outliers would not skew identification of who might benefit from additional coaching. When using any analytics tool, it is essential to understand the definitions of the numerators and the denominators. Emory’s patient count in the denominator was based on the number of signed notes; thus, if a physician was behind in signing notes, the denominator would be smaller and significantly increase his or her average time for each metric. For this reason, several months after go-live, Emory began delaying review of the data by a month to give the providers time to complete their notes and thus increase the accuracy of the denominators.

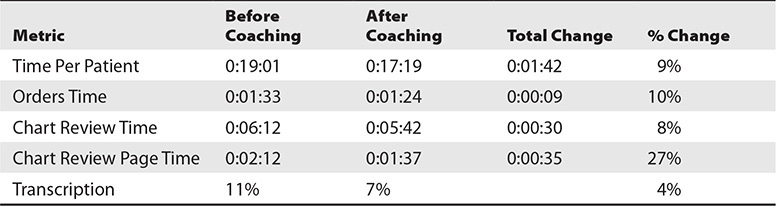

Emory used the data to determine which physicians would be targeted for one-on-one coaching. Initially Emory targeted all physicians who were above average in their use of traditional transcription, since one of the project goals was to reduce the cost of transcription. Emory also targeted physicians who were above the mean or median for the total amount of time per patient or pajama time. During the first round of targeted coaching, 175 providers received additional assistance, the benefits of which are shown in Table 20-4.

Table 20-4 Select Provider Metrics Before and After a Focused Coaching Intervention During an EHR Optimization Project

Emory continues to monitor data monthly and uses it to proactively reach out to physicians who may be struggling or have opportunities to increase their efficiency. Prior to analytics, our support team had to wait until a physician or administrator complained, and usually by that time, the physician had been unhappy or struggling for a prolonged time. Having the analytics has significantly increased our training team’s efficacy. Additionally, they use the data to assess whether the coaching had an impact after a given intervention.

Banner Provider Go-Live Metrics

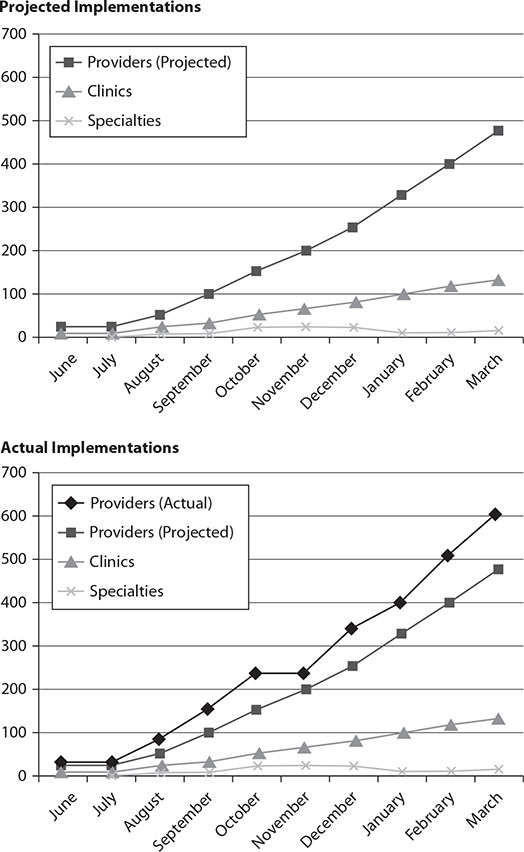

Banner’s go-live plan included a ten-wave implementation spanning nine months, with a target of bringing up 490 providers across 110 clinics.

The initial goal and timeline was to implement 25 providers per wave in the first two monthly waves, increase to 50 providers per wave as the process was improved, and finally increase to 75 providers per wave. Interestingly, as the initial waves were implemented successfully, providers who were scheduled in future waves began to request to move up their go-live dates. As the implementations progressed, Banner was able to exceed its goal by more than 25 percent above projections by the tenth wave and all ambulatory providers were fully implemented by the end of 2016. See Figure 20-4.

Figure 20-4 Cumulative number of providers and clinics that “went live” during a ten-wave EHR implementation, projected vs. actual

Chapter Review

Following a proven plan for implementing an EHR will increase the likelihood of your success. Understanding what challenges you might encounter will help you to prepare for those obstacles or perhaps even avoid them.

The following points summarize critical success factors for large-scale EHR implementations discussed in this chapter:

• Begin with your organization’s guiding principles based on its mission and then connect those principles to project goals like standardizing care or decreasing medical error.

• Ensure that a governance structure has been developed to navigate the changes.

• Create a very detailed project plan that will guide you and keep you on track through the project.

• Identify and enlist clinical leaders from the beginning.

Recognize that the success of your implementation depends on how well you manage the change. After all, implementing a new EHR is not as much an IT project as it is a change management project and behavioral modification. Help your providers to understand that to really get the most out of an EHR system, they must realize that it is not simply a re-creation of the paper chart in a digitized form. It is a dynamic, ever-changing record, and the quality of what can be retrieved from the system is only as good as what the user puts into it. When physicians can see this true value, they will begin to use the system differently, inputting more useful information. Only then will they be able to move from merely accepting the new electronic changes to actually using the system fully to improve patient outcomes.

Questions

To test your comprehension of the chapter, answer the following questions and then check your answers against the list of correct answers that follows the questions.

1. Rogers’ theory called diffusion of _________________ has been used as a change management framework to guide healthcare EHR implementation projects.

A. electronic health records

B. electronic medical records

C. transformation

D. innovations

E. technology

2. HIT large initiative governance has which of the following hallmark(s)?

A. It includes and is accountable to all relevant stakeholders.

B. Guiding principles based on the organization’s mission.

C. It is transparent to all constituents to assure decisions are fair and equitable.

D. Its project leaders use online collaboration tools to optimize involvement and dissemination.

E. All of the above.

3. Members of executive leadership must be willing and able to recognize and remove barriers encountered by the EHR and HIT implementation teams. Which of the following is an effective way for them to accomplish this?

A. Active involvement on an HIT or EHR steering committee

B. Receiving “back channel” communication from important physicians in the organization

C. Attending weekly project management meetings

D. Sponsoring celebrations upon completion of major project milestones

4. Which of the following is an important consideration for creating order sets?

A. They should only be created after go-live.

B. Since physicians sign the order sets, they should be the only clinical care team members involved in their development.

C. Since order sets have a significant effect on the work of many different care team members, representatives of those disciplines should participate in order set development.

D. Order sets should be evidence-based and as such should never be adjusted for local healthcare organization reasons.

5. Clinical documentation templates _________________.

A. cannot vary across clinical or medical specialties

B. include required fields to foster compliance with regulations or standards

C. can accommodate any possible permutation of healthcare

D. should not be used, as the best practice for clinical documentation is free text entry

6. Which of the following workflows should be addressed during an EHR implementation?

A. Pharmacy prescription dispensing

B. Disaster preparedness

C. Handoffs between clinical care teams

D. Executive leadership participation in important project meetings

7. EHR downtimes can occur due to _________________.

A. temporary loss of network connectivity

B. malfunction of interfaces

C. scheduled time to perform system upgrades

D. all of the above

8. Which of the following metrics is used to assess provider performance and/or satisfaction after EHR or HIT go-lives?

A. Orders time (average amount of time spent using the ordering tools per patient)

B. Issues documentation time (average amount of time spent documenting issues with the system per provider)

C. Boot camp time (minutes spent in remediation training per provider)

D. Global job satisfaction scores

Answers

1. D. Rogers’ theory called diffusion of innovations has been used as a change management framework to guide healthcare EHR implementation projects.

2. E. HIT large initiative governance has the following hallmarks: it includes and is accountable to all relevant stakeholders, with guiding principles based on the organization’s mission; it is transparent to all constituents to assure decisions are fair and equitable; and its project leaders use online collaboration tools to optimize involvement and dissemination.

3. A. An effective way for members of executive leadership to recognize and remove barriers encountered by the EHR and HIT implementation teams is to be actively involved on a HIT or EHR steering committee.

4. C. Since order sets have a significant effect on the work of many different care team members, representatives of those disciplines should participate in order set development.

5. B. Clinical documentation templates include required fields to foster compliance with regulations or standards.

6. C. Handoffs between clinical care teams should be addressed during an EHR implementation.

7. D. EHR downtimes can occur due to temporary loss of network connectivity, malfunction of interfaces, and scheduled time to perform system upgrades.

8. A. A metric used to assess provider performance and/or satisfaction after EHR or HIT go-lives is orders time (average amount of time spent using the ordering tools per patient).

References

1. Charles, D., Gabriel, M., & Searcy, T. (2015). Adoption of electronic health record systems among U.S. non-federal acute care hospitals: 2008–2014. ONC Data Brief, no. 23. Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology.

2. McCormick, K., & Gugerty, B. (2013). Healthcare information technology exam guide for CompTIA® Healthcare IT Technician and HIT Pro™ certifications. McGraw Hill-Education.

3. Rogers, E. M. (2003). Diffusion of innovations, fifth edition. Simon and Schuster.

4. Monegain, B. (2015, Apr. 3). Banner Health, Cerner tackle big change. HealthcareIT News. Accessed on June 9, 2016, from www.healthcareitnews.com/news/banner-health-cerner-take-big-change.

5. Office of the National Coordinator for Health IT (ONC). (n.d.). Chart migration and scanning checklist. Accessed on June 30, 2016, from https://www.healthit.gov/providers-professionals/implementation-resources/chart-migration-and-scanning-checklist.

6. ONC. (n.d.). Meaningful use definition & objectives. Accessed on November 28, 2016, from https://www.healthit.gov/providers-professionals/meaningful-use-definition-objectives.