CHAPTER 28

Healthcare Information Security: Operational Safeguards

Sean Murphy

In this chapter, you will learn how to

• Define operational safeguards

• Apply operational safeguards within a healthcare setting

• Explain the value of an information security management process that includes information security training and awareness

• Assess risk in healthcare organizations using a framework of standards-based criteria

• Identify operational safeguard fundamentals within emerging healthcare initiatives

Operational Safeguards: A Component of Information Security

Operational safeguards are correct processes, procedures, standards, and practices that govern the creation, handling, usage, and sharing of health information. They are an important piece of the “due care” and “due diligence” any healthcare organization must perform.1, 2 A distinction must be made between these and administrative, physical, and technical safeguards. While the administrative, physical, and technical safeguards are important by themselves, they must be integrated to completely protect health information and systems. To implement a process that provides layers of protection, like defense in depth, where a robust and integrated set of measures and actions are in place that focus in a variety of security areas, operational safeguards must be added to any overall security program to achieve compliance.3

Due care and due diligence relate to processes and actions a company takes that are considered responsible, careful, cautious, and practical. Due care and due diligence are defined as follows:

• Due care Steps taken to show that a company has taken responsibility for the activities that occur within the corporation and has taken the necessary steps to help protect the company, its resources, and employees.

• Due diligence The process of systematically evaluating information to identify vulnerabilities, threats, and issues relating to an organization’s overall risk.

Conceptually, due diligence and due care are a pathway for the flexibility a healthcare organization needs to conduct information-sharing securely, yet within the constraints of information protection.

Operational safeguards apply to information security practices that are required in all industries—banking, manufacturing, retail, and so forth. But this chapter will focus on the operational safeguards required for healthcare, where there are similarities but also unique challenges for providing information security.

Operational Safeguards in Healthcare Organizations

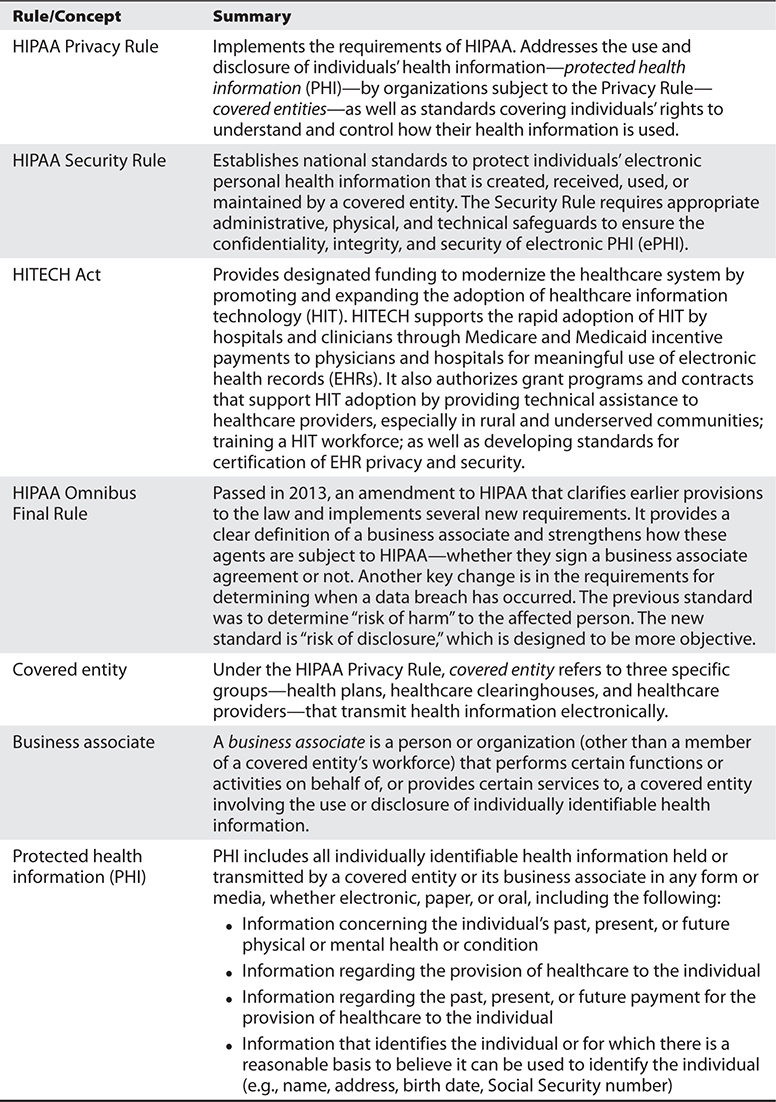

No organization can totally eliminate the risk of improper disclosure of health information. In fact, within a healthcare organization, the Heath Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) of 1996 permits certain incidental uses and disclosures that happen as a by-product of another permissible or required use or disclosure, as long as the covered entity has applied reasonable safeguards.4 An incidental use or disclosure does not invalidate an organization’s operational safeguards.5 Operational safeguards apply to healthcare organizations because of HIPAA and all of its amendments. The power of the federal government to enforce HIPAA compliance through fines and penalties stems from one of these amendments, the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health (HITECH) Act of 2009. The administrative simplification provisions of HIPAA called for the establishment of standards and requirements for transmitting certain health information to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of the healthcare system while protecting patient privacy.6 HITECH as an amendment to HIPAA followed the HIPAA Privacy Rule (2002) and the HIPAA Security Rule (2003). It was enacted as part of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) of 2009 to promote the adoption and meaningful use of healthcare information technology and addresses the privacy and security concerns associated with the electronic transmission of health information, in part through several provisions that strengthen the civil and criminal enforcement of the HIPAA rules.7 HIPAA governs organizations that provide certain services using protected health information (PHI). Table 28-1 provides a foundational summary and definitions for some of the most important concepts and terms relevant to understanding healthcare information security.

Table 28-1 Understanding HIPAA: Basic Definitions

What is important to the understanding of operational safeguards in healthcare is that all covered entities and business associates must put provisions in place to use PHI appropriately and not disclose any PHI inappropriately. When a covered entity or business associate does disclose PHI inappropriately, they may have committed a PHI breach. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) oversees the U.S. laws applicable to these breaches. Over the last several years, HHS has handed out numerous monetary fines (and a few jail terms) for organizations and individuals who have committed PHI breaches. Here are just a few highly publicized examples from the news headlines:

• Triple-S Management Corp., an insurance holding company based in San Juan, Puerto Rico, was slapped with $6.8 million in penalties in 2014 for improperly handling the medical records of some 70,000 individuals.8

• As many as 80 million customers of the nation’s second-largest health insurance company, Anthem, Inc., have had their account information stolen. “Anthem was the target of a very sophisticated external cyber attack,” Anthem president and CEO Joseph Swedish said in a statement. The hackers gained access to Anthem’s computer system and got information including names, birthdays, medical IDs, Social Security numbers, street addresses, e-mail addresses, and employment information, including income data.9

• A medical group in Texas is facing a potential healthcare data breach that may have exposed patient and employee information after a hacking incident. Approximately 50,000 individuals were affected by the healthcare data security event at the Medical Colleagues of Texas, LLP. Medical Colleagues of Texas, LLP stated that it discovered an outside entity had accessed its computer network, which stored EHR and personnel data.10

As HITECH has opened the door for all 50 U.S. states and territories to also sue for damages due to a PHI breach, the potential for an organizationally disastrous impact of just one breach is highly likely.

TIP Per 45 CFR 164.408, if a disclosure is determined to be a breach, it must be reported to HHS immediately if it affects 500 or more individual records. At lower levels, covered entities are required to keep a log and report breaches annually.

The operational safeguards are critical to maintaining a high level of trust between the individual and the organization that uses their information. When a patient heads to their family physician for a routine check-up or visits the hospital for a more intensive procedure, they deserve to know that the information they share is kept confidential. Patients in any medical setting want to rest assured that their personal information is not going to be available to anyone other than the physicians and medical staff involved in their care. Even if patients generally trust their care providers, studies have shown they do not extend that same level of trust when the information is digitized or transferred to electronic information. In one study, 35 percent of respondents indicated they are worried that their health information will end up widely available on the Internet. Half of the respondents believe that EHRs will have a negative impact on the privacy of their health data. Only 27 percent of respondents felt computerized health records would have a somewhat positive or significantly positive effect on their privacy. Another 24 percent said that computerized health records would have no impact on privacy at all. Interestingly, 24 percent of respondents said they don’t even trust themselves with access to their own records.11

Beyond the impact a PHI breach can have on an organization, the impact of a healthcare provider not having access to information they need to provide diagnosis, treatment, and make any other health-related decisions can be critical. Of the traditional information security concerns—confidentiality, integrity, and availability—availability of information is uniquely and exceedingly important within healthcare. The root cause of medical and diagnostic errors is often patient information that is not available when the provider needs it—at the time of patient care. Even in nonemergency situations physicians are forced to provide care, usually by asking the patient (who may or may not provide accurate information). In worse cases, a doctor may need to rely on what the family member(s) can recollect—if anything at all. Redundant tests, inefficient care, delay in treatment, and patient safety risk are all outcomes of providers lacking information—irrespective of the confidentiality or integrity concerns that are also important. Having secure information available is vital to avoiding medical errors. This represents a major challenge for healthcare organizations and is illustrated in the seminal and still relevant Institute of Medicine’s (IOM) report, To Err Is Human (2000). The IOM also highlights the role unavailable information has in patient safety and causing medical errors.

Another aspect of information availability is system or network downtime. While these are traditionally covered by technical controls, downtime can also be prevented and mitigated using numerous operational (nontechnical) safeguards. Measures like contingency planning, manual processes, and disaster recovery are ways an organization can build in extra security for information availability. And downtime is very expensive. For instance, downtime can cost a practice with five physicians nearly $25,000 per instance when the system is down for ten hours or more. If systems are down just 4 percent of the time, the data predicts the cost could top $234,000 annually. We also must factor in the cost of recovery from an unplanned event. A survey of healthcare providers showed, on average, that maintaining a 99 percent uptime still resulted in an average of 87 hours per solution rework annually for information systems (such as clinical patient record systems).12 Clearly, periods of information unavailability are not only dangerous, as we have already examined, they are also costly—putting patients’ lives at risk and healthcare organizations’ reputations in jeopardy.

Now that we have seen how operational safeguards are integral to information security (particularly availability) specific to a healthcare setting, the next step is to examine common components of a robust, integrated operational safeguard program in healthcare. All of the components discussed in the following sections are required by HIPAA and HITECH.

Security Management Process

One of the first operational safeguards is an obvious security management process. This is required by HIPAA for all healthcare organizations.13 A main provision of the security management process is that the organization must designate a “security official” and a “privacy official” to be responsible for developing and implementing security and privacy policies and procedures. This is critical, because protecting healthcare information permeates the entire organization—privacy and security of patient information is integral to every medical activity.

Information Management Council

Along with corresponding policies and procedures that provide governance for proper handling and protection of sensitive data (including PHI), implementing an information management council is an important operational safeguard. Depending on the overall governance structure of the organization, this group can be a council, a committee, or even a team. What matters is that the group is a formally chartered or organized collection of decision-makers in the organization. It should have an executive sponsor and be made up of people from strategic areas in the organization—not only from security, information technology, legal, and privacy, but also from clinical and business areas.14

Together this team considers and provides strategic direction for various aspects of protecting information. For instance, how an organization may migrate data to the cloud or implement a bring your own device (BYOD) policy would be issues the council addresses. The council does not replace the leadership and role of established positions like information security or privacy officers. In fact, the council leverages the reach and influence these positions can have in an organization by creating enterprise-wide awareness and shared priority.

Identity Management and Authorization

This is an operational safeguard that applies across all industries that care about information security. Being able to establish and validate the identity of each individual or entity with access to the system; assigning roles and providing appropriate authorizations to each identity; controlling the accesses related to those authorizations, including authenticating the asserted identity; terminating the authorizations as necessary; and maintaining the governance processes that support this life cycle are best practices no matter what the business.15 In healthcare, there are so many issues that are prevented or mitigated by implementing proper identity management and authorization processes. Obtaining unauthorized (free) care or illegally filled prescriptions via identity theft are prevalent issues—assuring that patients are who they say they are can mitigate those risks. Likewise, taking actions to enforce use of strong passwords and prohibit sharing of user credentials can prevent someone from using a doctor’s credential to access the computerized order-entry system and sign orders unlawfully.

In fact, the use of multifactor authentication is increasingly imperative to assure identity and access management due to the growing threat of credential theft. A hacker who has a valid username and password becomes indistinguishable from the authorized user. The protection methods of information security become effectively useless.

TIP Multifactor authentication is based on having two or more elements that make up the access, authentication, and authorization credentials for a user. It is considered a best security practice, reduces the impact of credential theft, and is based on the concept of identity established and verified according to16

—Who the user is, which is a given: Username (e.g.)

—What the user knows: Password (e.g.). These identifiers make up single-factor authentication.

—What the user has: A biometric marker (fingerprint) or public-key infrastructure (PKI) card. These identifiers make up multifactor or two-factor authentication.

Awareness and Training Programs

The HIPAA Security and Privacy Rules require all members of the workforce to be trained in security and privacy principles. The required training should take place at least once per year. But that does not preclude real-time awareness tips and education. Keeping the importance of HIPAA, safeguarding PHI, and complying with information security requirements as priorities in an organization (with dozens of competing priorities and scarce resources) is no easy task. However, a healthcare organization where safety, privacy, and security are part of the culture as opposed to a compliance requirement has a competitive advantage. And in those healthcare organizations where all employees feel individually responsible for protecting the confidentiality, integrity, and availability of health information and the privacy and safety of patients, organizational risk will be reduced and patient safety will be improved.

Risk Assessment

Risk assessment is the heart of any information security program in a healthcare organization. From a compliance perspective, HIPAA requires that an organization “conduct an accurate and thorough assessment of the potential risks and vulnerabilities to the confidentiality, integrity, and availability of electronic protected health information held by the covered entity.”17

Even if there were no legal or regulatory mandate, any good security management process would begin and end with a risk assessment. Within a risk assessment are objective standards that are based on industry standards and accepted practices, compliant with law, and adhere to ethical principles. Within HIPAA, a healthcare organization can defend itself against fines and penalties (and loss of public trust) by demonstrating what is called the “reasonable and prudent person” rule. As mentioned before, organizations must demonstrate due diligence and due care to convince the courts that their actions were not negligent. There are numerous examples of risk assessments. In general, they are systematic, ongoing, and conducted in identifiable phases. (This chapter does not elaborate on risk assessments; Chapter 26 examines risk assessment in greater detail.) HIPAA requires covered entities to protect against reasonably anticipated threats or hazards to the security/integrity of the e-PHI they create, receive, maintain, or transmit. They must also prevent reasonably anticipated impermissible uses or disclosures. A covered entity must reduce risk to reasonable and appropriate levels. The risk analysis process determines what is “reasonable.”

TIP See the HIMSS Risk Assessment Toolkit at www.himss.org/library/healthcare-privacy-security/risk-assessment for a variety of frameworks and other resources for conducting a risk assessment. Additionally, go to the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) Security Compliance Automation Protocol (SCAP) web site for access to the HIPAA Security Rule Automated Toolkit at https://scap.nist.gov/hipaa.

Software and System Development

Software and system development are important with respect to operational safeguards in that too often information security is “bolted on” at the end of development and during implementation. Operational safeguards, like risk assessments, need to be integrated into the identified phases of development—in other words, information security needs to be “built in.” Managing the software and system development life cycle is akin to managing the configuration process, but it is more focused on systems or software as they are being engineered before implementation. Generally speaking, the life cycles have four development phases, listed next. However, to properly build in information security, some operational safeguards must be attended to.18 The relative operational safeguards are listed in italics corresponding to the appropriate development phase.

• What Specification of WHAT the product is to do.

• Initiation An initial threat and risk assessment will provide input for IT security requirements.

• How Specification of HOW the product does it.

• Build Development or BUILD of the code or components that implements HOW.

• Design and development An appropriate balance of technical, managerial, operational, physical, and personnel security safeguards will help to meet the requirements determined by the threat and risk assessment.

• Use Operational deployment or USE of software or system that performs WHAT.

• Implementation Design documentation, acceptance tests, and certification and accreditation processes are created.

• Operation System security is monitored and maintained while threat and risk assessments aid in the evaluation of modifications that could affect security.

When developing software with operational safeguards built in, it is crucial to begin the process with the end in mind. A plan for disposal must also be built in to the system and software development life cycles. In accordance with archival and security standards and guidelines, the organization must plan to archive or dispose of sensitive IT assets and information once they are no longer useful.19

Configuration Management

Having control of how systems are developed and implemented is a crucial component of operational safeguards in healthcare organizations. Not many industries have systems as diverse as a healthcare organization. Traditionally, many systems and applications within healthcare are highly customized, commercial-off-the-shelf (COTS). For this reason, an operational safeguard for resources not fully developed by the healthcare organization is required. Configuration management controls provide the organization with a safe way to manage changes made to systems once they are in operation. Examples of bodies or systems that control configuration management are configuration control boards or system-change-request processes.20

Some of the types of systems that can be found within one healthcare organization fall into the following categories:

• Office automation IT (business and administrative functions)

• Financial systems connected to state and federal agencies as well as healthcare insurers

• EHR systems and clinical applications

• Medical devices regulated by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and manufactured/maintained by commercial vendors (e.g., PACS, telemetry, catherization labs).

Configuration management is an operational safeguard that creates processes for controlling how changes are made to a system and keeping records of those changes. It is good information security practice to control and document changes to the hardware, firmware, software, and documentation involved in protecting information assets. This configuration management process should be governed by the security management program an organization has in place. An additional measure that is an increasingly important safeguard is to use automated detection and alerting tools that identify when unexpected changes are made and notify security teams.

Consent Management

Revisiting the importance of having operational safeguards in place to ensure public (patient) trust in the organization, having a consent management process allows a patient to know how their information will be used. It also makes it possible for patients to control the use of their information. Numerous federal and state laws cover this safeguard, and HIPAA requires a consent management process. An organization must obtain a patient’s consent for collecting, retaining, or exchanging his or her personal health information. And when that information concerns behavioral health or substance abuse, additional restrictions and authorizations are needed. The consent process is extremely important as it relates to promises and obligations covered entities make to the patient. Today, these processes are primarily manual, but technologies emerging in advance of healthcare information exchanges (HIEs) and Integrating the Healthcare Enterprise (IHE) are building technical methods for obtaining and maintaining consent.

TIP IHE refers to a group started by radiologists and information technology professionals to address and improve how computers in heathcare share information. The group started their work in 1998 based on interoperability standards for healthcare-specific transmission formats like DICOM and HL7. Today, they provide numerous resources for healthcare organizations such as technical frameworks and a product registry.

System Activity Review

A comprehensive program of operational safeguards will include system activity review. This consists of trained and qualified personnel routinely reviewing records of information system activity. These reviews can come in the form of audit logs, facility access reports, and security incident tracking reports. Being vigilant in this area can be an effective means of detecting potential misuse and abuse of privileges. The need for this activity is growing with HITECH Act’s requirements for providing accounting of disclosures and notification to all patients affected by a data breach. The sheer volume of clinical and financial data is overwhelming. Where hospitals rely on manual auditing and reporting today, they will certainly be forced to move to automatic and technical solutions for running the reports. In fact, the technology exists today; it is just underused in the healthcare industry.21

TIP HITECH provides that an individual has a right to receive information about disclosures made through a covered entity’s electronic health record for purposes of carrying out treatment, payment, and healthcare operations.22

Continuity of Operations

Healthcare organizations are required to establish and implement policies and procedures for continuity of operations when unanticipated events, both natural and manmade, happen. Natural disasters, malware that causes systems to crash, and any other number of events that impede healthcare for measurable periods of time will happen. Healthcare organizations have always prepared to provide care in the face of mass-casualty emergencies or when power and water are unavailable. However, the loss of information availability or critical system access requires a different process. It is not practical to expect to go to a paper or manual process until a system or a data center is available again. Healthcare is more and more dependent on electronic health information. HIPAA requires operational safeguards that protect information continuity to be in place.23 The plan must include a prioritization of business and clinical systems with an order of restore. When the event happens is not the time to begin deciding which systems must be restored and in what order. Those decisions must be made when all conditions are normal.

Incident Procedures

Because the data breach rules are enforced with fines and penalties, it becomes a high priority of any healthcare organization’s awareness and training program to provide employees with a clear explanation of how incidents are reported. Incidents can be a virus received in an e-mail, a medical record found in a public area, or some other breach of sensitive PHI. Not all disclosures or incidents are breaches that require notification, so healthcare organizations need to design and implement a proper response that includes a full investigation. In some cases, the organization will need to notify individuals whose health information may have been exposed. There has been a significant change in data breach notifications that is important to an organization and its incident response procedures. Previously, under the HITECH Act, healthcare organizations conducted a risk assessment of the data disclosure to determine if there was any impact or harm to the patient. It was the organization’s responsibility to make notification if they determined there was a likelihood of negative impact on the affected individual. Under the amendment to HIPAA called the Omnibus Final Rule in 2013, the burden shifted to determining the risk of disclosure. The law removes any measure of impact and makes the threshold simply a measure of how likely it is that the data was exposed to an unauthorized entity.24

Sanctions

The HIPAA law outlined penalties in the event of unauthorized disclosure, but the HITECH Act enacted severe civil and criminal penalties for sanctioning entities that fail to comply with the privacy and security provisions. In addition to patient notification requirements, healthcare organizations are required to take remedial actions, document actions taken, and discipline (up to and including firing) their employees when privacy and security policies and procedures are not followed correctly.

Evaluation

Drawing from the basic “plan, do, check, act” cycle of quality management, a healthcare organization should periodically evaluate the security management program in place. This should be done at least annually and include objective measures of success. An independent review is a key component of this yearly process. That does not preclude internal review, but every effort must be made for objectivity. Another time to evaluate operational safeguards is when material changes are made within the organization that might impact the security management program. A good example of such a change would be a merger or acquisition of a new medical group practice or the opening of a new surgical service center off campus. These changes will alter the risk to which the organization can be exposed.

Business Associate Contracts

Unique to healthcare entities subject to HIPAA, business associate (BA) contracts are a source of operational safeguards. All organizations have contractual obligations and service providers that must be considered when operating a security management program. Within healthcare, HIPAA mandates these agreements be in place and include satisfactory assurance that appropriate safeguards will be applied to protect the PHI created, received, maintained, or transmitted on behalf of the covered entity.25 BA agreements help manage risk and bound liability, clarify responsibilities and expectations, and define processes for addressing disputes among parties. The BA contract requires that each person or organization that provides certain functions, activities, or services to the healthcare organization involving PHI is obligated to comply with HIPAA requirements. The HITECH Act subjects the BA to the same enforcement and sanctions as the healthcare organization they support.

Healthcare-Specific Implications on Operational Safeguards

The need to implement operational safeguards applies to various industries—banking, manufacturing, energy, and healthcare, to name a handful. Across these industries, information security professionals have to be flexible enough to apply information security best practices while enabling maximum business capability at appropriate cost. Across these industries, the common constraints are the unique features of the business and how these features impact implementing security measures. Healthcare is no different. Health information security professionals need to be on top of the latest advances in information technology, including operational safeguards, all the while making accommodations for the requirements of the healthcare organization.

Networked Medical Devices

Medical devices present a unique challenge within a healthcare environment. An increasing number of medical devices connect to the hospital network or use network resources to operate. Expanding on the FDA definition of a medical device, a networked medical device is a special-purpose computing system including an instrument, apparatus, or implant intended for use in the diagnosis of disease or other conditions or in the cure, mitigation, treatment, or prevention of disease, or intended to affect the structure or any function of the body.26

Some examples of networked medical devices include digital imaging machines, telemetry systems, linear accelerators, and infusion pumps. Although they are typically built upon standard IT operating systems and run well-known applications, their special-purpose nature means that the normal operational safeguards that would be appropriate in office automation IT could cause patient harm when indiscriminately applied to medical devices.27 This fact has introduced a new term into the healthcare information security lexicon. E-iatrogenesis is any patient harm caused at least in part by the application of healthcare information technology (and, by extension, healthcare information security efforts).28 This term evolves from iatrogenesis, which is an inadvertent adverse effect or complication resulting from medical treatment or advice from a healthcare provider.

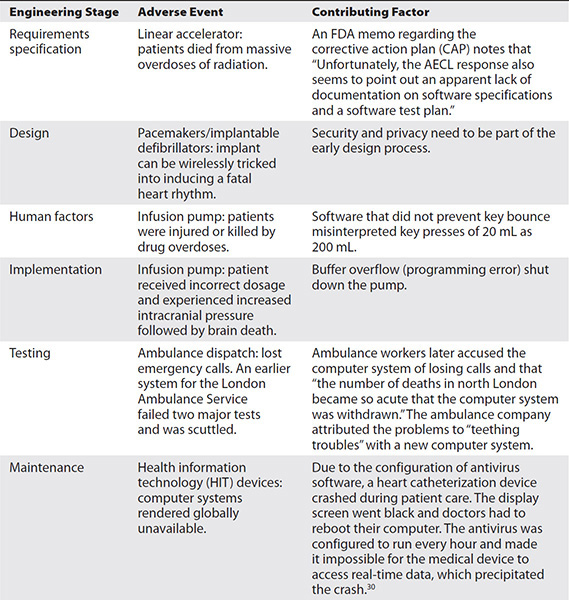

An example of e-iatrogenesis is when a prescription for a drug is not cross-referenced with the current patient medication list and the new drug causes an adverse reaction when combined with the medications the patient currently takes. Table 28-2 highlights some real-life examples of episodes of e-iatrogenesis that have occurred at various engineering stages of medical devices.29

Table 28-2 Examples of Adverse Events Where Medical Device Software Played a Significant Role

Multiple-Tenant Virtual Environments

With the onset of the “cloud” computing environment, healthcare organizations looking for efficiency, cost reduction, and expert IT support are quickly entering into the virtual computing environment. Today’s IT infrastructure too often suffers from single-purpose server and storage resources, which result in low utilization, gross inefficiency, and an inability to respond quickly and flexibly to changing business needs. Sharing common resources and delivering IT as a service (ITaaS) from an offsite data center or purchased from a cloud services provider (e.g., Amazon Web Services [AWS] or Microsoft Azure) promises to overcome these limitations and reduce future IT spending. The trend in IT spending is to move to the cloud instead of investing in infrastructure, with 59 percent of those surveyed in the 2017 Computerworld Forecast Study responding that software as a service (SaaS) and a mix of public, private, hybrid, and community clouds are most likely to have an impact on their organization in the next three to five years.31

However, within the cloud data center, typical cloud providers have numerous customers. These customers have varied IT security requirements, ranging from almost none to very secure. Because healthcare is a highly regulated industry, healthcare organizations that enter into cloud computing agreements for service must ensure that their specific operational controls are in place and exercised. While subject to HIPAA, the healthcare organization as a covered entity cannot side-step requirements to safeguard PHI because other tenants within the multiple-platform virtual environment have less rigid requirements. The lack of confidence that data and applications will be securely isolated has been a major impediment to adoption of cloud-based services in healthcare. Healthcare IT professionals must be certain that applications and data are securely isolated in a multitenant environment where servers, networks, and storage are all shared resources. Additionally, the contractual agreements that must be established between the covered entity and the business associate data center must also account for HIPAA provisions for backup and recovery processes that may be more rigorous than the processes of other tenants in the environment. A very important point, with the passing of the HIPAA Omnibus Final Rule, HHS clarified the definition of a business associate and made certain that cloud providers were subject to HIPAA.

NOTE The final rule (https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-2013-01-25/pdf/2013-01073.pdf) does not specifically mention “cloud.” However, using the definitions section of the final rule and the clarification found at “Guidance on HIPAA & Cloud Computing” on https://www.hhs.gov/hipaa/for-professionals/special-topics/cloud-computing/index.html as guidance, the applicability to cloud providers is demonstrated.

The tools, processes, and people skills needed by a healthcare organization will change as the healthcare organization moves data, infrastructure, and services to the cloud. However, the requirements for assuring data protection will not.

TIP For students interested in further study on the changing nature of cybersecurity in cloud environments, the Cloud Security Alliance is useful as a starting point. Their mission is “To promote the use of best practices for providing security assurance within Cloud Computing, and provide education on the uses of Cloud Computing to help secure all other forms of computing (https://cloudsecurityalliance.org).”

Mobile Device Management

Another trend in every industry is the use of mobile devices. Healthcare is no different. Many healthcare providers are enticed by the idea of allowing caregivers, administrators, and patients to use their own tablet computers, notebooks, and smartphones to access healthcare resources. However, they are concerned about the security risks—and the impact on IT operations. In fact, the pressures for mobile device use are extensive in healthcare. Statistics such as “81% of employed adults use at least one personally owned device for business use” and “Apple shipped more iPADs in 2 years than MACs in over 20 years”32 are eye-opening. Bring your own device (BYOD) efforts are increasing as physicians and other caregivers want to use their smartphones and tablet computers for ordering prescriptions in computerized provider order entry (CPOE).

These BYOD efforts introduce unique challenges to the operational safeguards in terms of the devices’ portability, their varying configurations, and the lack of control the organization has on any third-party software already loaded on the device. Equally eye-opening statistics point to the vulnerabilities inherent in these mobile devices: “$429,000 is the typical large company loss due to mobile computing mishaps in 2011” and “1/2 of companies have experienced a data breach due to insecure devices.”32

Operational Safeguards in Emerging Healthcare Trends

Operational safeguards impact healthcare operations in all clinical and business processes—wherever confidentiality, integrity, and availability must be assured. This is true in existing processes and legacy systems. It is also true when examining emerging healthcare trends. A few select advances and initiatives demonstrate this reality and are presented here.

Healthcare in the Cloud

As mentioned before, healthcare organizations are moving to the cloud in meaningful ways. Business associate agreements will need to become more cloud-friendly.33 As David S. Holtzman, formerly of the Health Information Privacy Division of the Office for Civil Rights (OCR), said, “If you use a cloud service, it should be your business associate. If they refuse to sign a business associate agreement, don’t use the cloud service” (during a speech at the Health Care Compliance Association’s 16th Annual Compliance Institute).

It bears restating that cloud computing offers significant benefits to the healthcare sector. Healthcare providers desire quick access to computing and large storage facilities that are either not available in traditional settings or just too expensive. The need for healthcare organizations to routinely share information securely across various settings and geographies places a burden on the healthcare provider and the patient. There can be significant delay in treatment and loss of time, which translates into increased cost to the system. The benefits of cloud computing address these realities by giving healthcare organizations a way to improve healthcare services and operational efficiency—and reduce costs over the long term. The other side of the coin is that healthcare data has specific requirements under HIPAA and HITECH that cloud providers may not be prepared to follow.34 Whereas in the recent past many cloud vendors did not appear to fully understand the importance of addressing the special considerations within healthcare, the HIPAA Omnibus Final Rule in 2013 clarified the issue. With respect to the definition of a business associate, HHS has been clarified to include cloud service providers. Also, HHS went on to decree that even if a cloud service provider (or any entity performing a role subject to HIPAA) does not actually sign a business associate agreement, that does not excuse them from the law. They are subject to HIPAA regardless of whether they actually sign the document.

Healthcare organizations considering cloud computing need to carefully consider the risks before taking the plunge, and then take the right steps to obtain adequate due-diligence protection. According to Rebecca Herold, CEO of The Privacy Professor, a healthcare information security professional must know the key security issues for cloud computing in healthcare:

• Cloud computing safeguards necessary to satisfy HIPAA and other privacy and security requirements

• The impact of standards, for example, accounting of disclosures

• The negotiation of a HIPAA-compliant business associate agreement with the cloud vendor

• How to effectively obtain assurance that cloud vendors are in compliance with HIPAA

• Metrics to use to determine that vendors maintain compliance on an ongoing basis

• Performance issues, including availability of data and services

• Increased complexity of e-discovery if processes and/or data storage are handled using cloud computing

• Handling the transition to another cloud vendor or back to the healthcare organization without disrupting operations or conflicting claims to the data35

International Privacy and Security Concerns

HIPAA security standards apply to covered entities within the United States; if your data is being hosted overseas in a cloud vendor arrangement, the same privacy and security laws may not apply. However, the international laws may be even more restrictive:

Personal data protection is a fundamental human right….

—Code of EU Online Rights (2012)

The important point is for a healthcare organization to know where their data lives and how it is transferred as it is being shared and used. The physical location of data stores brings up the varying international laws governing privacy and security that come into play—they must be addressed in business associate agreements and other binding contractual terms and conditions.36

Health Information Exchanges

As PHI becomes more digital and automated through EHRs, the movement toward health information exchanges (HIEs) is accelerating. For the most part, HIEs enable healthcare providers across the same or multiple organizations almost real-time access to clinical information, reducing the delay in information transfer in the traditional paper-based system. Built into the HIE is the ability to ensure information integrity if operational safeguards are integrated. Because of the availability of the PHI, HIEs may also provide a way for healthcare organizations to accomplish public health reporting, measure clinical quality, conduct biomedical surveillance, and perform advanced population health research. But this is only true if the element of trust is present and the PHI is deemed reliable from all perspectives—those of the patient, the provider, and the HIE activity.

HIEs are subject to HIPAA rules. Patients have specific rights as to how their information is used and disclosed. HIEs are required to publish their practices and inform participating patients of their individual rights. The only way to build trust is to communicate these terms and conditions clearly. The Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology (ONC) has produced a Nationwide Privacy and Security Framework for Electronic Exchange of Individually Identifiable Health Information. This framework outlines principles that, when taken together, constitute good data stewardship and form a foundation of public trust in the collection, access, use, and disclosure of PHI information by HIEs. Along with the ONC framework, the OCR published a series of fact sheets to assist HIEs in building privacy policies and explain how HIPAA applies. A summary of the ONC privacy and security framework can be found in Chapter 25, Table 25-1.

Workforce Information Security Competency

HIPAA requires that within a covered entity’s environment, workforce members who need access to PHI to carry out their duties must be identified.37 As healthcare information security processes mature over time, it is important to not only identify these individuals but ensure they are trained and competent. One model for this is the U.S. Department of Defense’s Instruction 8570.01-M, Information Assurance Workforce Improvement Program.38 It will become increasingly important to have certification programs that aid in assessing workforce competency, because the HHS Office of Civil Rights healthcare auditing process looks at workforce security competency and assesses directly against the following criteria:

Summary of Principles from OCR’s Audit Protocol Edited

• Inquire of management as to whether staff members have the necessary knowledge, skills, and abilities to fulfill particular roles.

• Obtain and review formal documentation and evaluate the content in relation to the specified criteria.

• Obtain and review documentation demonstrating that management verified the required experience/qualifications of the staff (per management policy).

• If the covered entity has chosen not to fully implement this specification, the entity must have documentation on where they have chosen not to fully implement this specification and their rationale for doing so.39

In light of this, healthcare organizations will want to identify and qualify workforce personnel who perform information security functions focusing on the development, operation, management, and enforcement of security capabilities for the organization’s systems and networks. As a condition of working information security positions, workforce competency will have to be a sustained effort, not a one-time event.

Accountable-Care Organizations

An emerging healthcare organizational construct, an accountable-care organization (ACO) is a legal entity recognized and authorized under applicable state law. It is composed of certified Medicare providers or suppliers. Participants come from both previously affiliated and unaffiliated healthcare organizations and work together to manage and coordinate care for a defined population of Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries. The ACO has a shared governance that provides appropriate proportionate control over the new organization’s decision-making process as priorities may conflict with individual member organizations’ missions and objectives.

The motivation for participating in an ACO extends beyond a desire for improved population health. ACOs that meet specified quality performance standards are eligible to receive payments for shared savings. These shared savings come from reducing spending growth below target amounts in Medicare.40 HIPAA allows the use and disclosure of PHI within a healthcare organization for treatment, payment, and healthcare operations by and between the hospital and its medical staff. ACOs extend the HIPAA guidelines beyond the internal healthcare organization. For this reason, ACOs will have to revisit their own internal operational safeguards with respect to HIPAA and ensure they are addressed in the framework of the ACO. An unauthorized disclosure of PHI by one member healthcare organization in the ACO could create significant risk both for the ACO and its participating providers.41

Use Case 28-1: Expensive Data Breaches Can Occur When Operational Safeguards Are Not in Place

An important operational safeguard in healthcare is the business associate agreement (BAA). This special type of contract is between a covered entity and vendor organizations that are subject to HIPAA law; that designation qualifies the vendor organization as a business associate. A primary reason these agreements are so important is that their terms and conditions outline additional operational safeguards that the covered entity will expect to be in place, such as a risk assessment requirement, written incident procedures, and a system activity review, which can include audit by the covered entity. Without these BAAs, the risk that a business associate will be the source of a data breach due to incompetence or ignorance of their obligations under HIPAA goes up measurably. One such example is the case of North Memorial Health Care of Minnesota.

North Memorial had a contractual relationship with Accretive Health, Inc. that involved access and use of PHI. When Accretive Health disclosed that they had an employee lose a laptop containing PHI that was not adequately encrypted, several operational safeguards were found lacking or missing altogether. While having the safeguards in place does not guarantee a data breach cannot happen, the risk would have been minimal had North Memorial taken the following precautions:

• Properly executed a BAA with Accretive Health so that the business associate would clearly understand its obligations to North Memorial under the law.

• The BAA also would have addressed the acceptable uses and disclosures for PHI on the part of the business associate and held them liable for unauthorized disclosure.

• Incorporated in the BAA an encryption requirement for laptops and mobile devices.

• Adequately protected the volumes of PHI stored, especially in mobile devices.

The original accounting to HHS stated that 2,800 patients were potentially affected, but that number was later revised to add an additional 6,697 patients.

Although the actions described in this scenario happened mostly in 2011, the investigation and negotiation of a resolution agreement stretched out until March 2016. HHS announced in a press release in that month that North Memorial Health Care will pay approximately $1.5 million in HIPAA settlement fines and implement a corrective action plan (including having a properly executed BAA) and proper training for employees.42

Meaningful Use Privacy and Security Measures

For healthcare organizations, meaningful use (MU) was established as a provision for financial payments of federal funds for early adopters of electronic health records under the ARRA Medicare and Medicaid EHR incentive programs. The act also established penalties for healthcare organizations that fail to implement EHRs and demonstrate MU against baseline criteria by a future date. To meet MU criteria, healthcare organizations must not only implement EHRs but also attest that security practices are in place to protect the confidentiality, integrity, and availability of electronic health information. Further, MU is a demonstrated ability to facilitate electronic exchange of patient information, submit claims electronically, generate electronic records for patients’ requests, or e-prescribe. Obviously, operational safeguards and HIPAA compliance are important considerations.

HIPAA privacy and security requirements were embedded in the ARRA Medicare and Medicaid EHR incentive programs. To meet the baseline requirements in the first stage of meaningful-use adoption, eligible providers needed to “attest” that they had conducted or reviewed a security risk analysis in accordance with HIPAA requirements and correctly identified security deficiencies as part of the risk-management process.43

Complying with privacy and security requirements to meet MU baselines in stage 1 and subsequent stages is vital to healthcare organizations that desire to receive the ARRA stimulus funds and, later, avoid penalties. For many organizations, if not all, the stimulus money subsidized a terrific cost outlay for implementing an EHR system. But failing to take privacy and security into account can be a deal-breaker. Devin McGraw, HHS OCR Deputy Director for Health Information Privacy, asserted that providers and hospitals who are fined for significant civil or a criminal HIPAA violation should be ineligible for healthcare IT incentive payments. In short, you cannot be “meaningfully using” healthcare IT if you are willfully neglecting or intentionally violating federal health privacy and security rules.44

As of April 2015, the meaningful use program was effectively replaced by Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act (MACRA). A portion of that act relates to this progression of meaningful use phases from 1 to 2 to 3. MACRA sets the end date for meaningful use payments by 2018. Rather than reimbursement incentives, MACRA implements a Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS), which incorporates meaningful use. The relevance to operational safeguards in this change remains. For instance, failure to meet a performance measure in the MIPS advancing care information performance category, like failure to conduct a risk analysis, results in a score of zero. For more information about the scoring methodology under MIPS, a download of the MACRA Fact Sheet “Cross Cutting Measures: Privacy & Security” is available at www.himss.org/macra-fact-sheet-cross-cutting-measures-privacy-security.

Chapter Review

Healthcare organizations are in the most exciting times of change and disruptive innovation ever. The great promise of information technology (in which EHRs and information sharing play a lead role) is that it will enable providers and researchers to improve patient care dramatically and produce an equally dramatic reduction in costs over time. But underlying these improvements are the imperative components of information availability and trust. The only way to achieve information availability and trust is to have a solid information privacy and security program within a healthcare organization. At the heart of the program are operational safeguards that include a security management program, a systematic and recurring risk assessment, and workforce training and awareness.

In this chapter you have learned what operational safeguards are and how they apply within a healthcare setting. HIT professionals will need to realize their responsibilities and become competent in operating in the healthcare environment. This chapter explained the value of an information security management process that includes information security training and awareness. Such a process will include a risk assessment process using a framework of standards-based criteria. Properly done, a risk assessment provides a roadmap for prioritizing improvements and maintaining compliance. Finally, we identified a few operational safeguard fundamentals with respect to their applicability within emerging healthcare initiatives. To capitalize on these, healthcare organizations must do more than acknowledge and comply with the HIPAA and HITECH requirements for privacy and security. They must use operational safeguards, one element of comprehensive administrative, physical, and technical controls, to lead their healthcare efforts over the next few tumultuous decades.

Questions

To test your comprehension of the chapter, answer the following questions and then check your answers against the list of correct answers that follows the questions.

1. What are the correct processes, procedures, standards, and practices governing the creation, handling, usage, and sharing of health information called?

A. Technical standards

B. Administrative safeguards

C. Operational safeguards

D. Physical standards

2. What is a covered entity that inadvertently discloses protected health information on 500 or more individuals required to do?

A. Report a breach to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

B. Conduct an investigation to recover the data so they do not have to report it

C. Contact the patients to see if they have had any credit report issues

D. Ensure the records were backed up so there is another copy

3. Big Bull Community Hospital signs an agreement with a “cloud” vendor to host their applications and data. The vendor will provide storage and continuity-of-operations support to include disaster recovery. As a covered entity subject to HIPAA law, Big Bull must insist on all of the following, except

A. PHI should not be stored on shared resources with other tenants’ data.

B. Adequate bandwidth for data availability is a HIPAA requirement.

C. Disaster recovery requirements are not lessened because other tenants compete for resources or have lesser recovery requirements.

D. Big Bull should require the cloud vendor to sign a business associate agreement.

4. Which of these is the most recent of the HIPAA amendments?

A. HITECH Act

B. Omnibus Final Rule

C. Privacy Rule

D. Security Rule

5. Of the following, which is the appropriate approach to operational safeguards for a healthcare organization to require from a cloud services provider?

A. Sign a contract to transfer security responsibility to the cloud services provider

B. Reduce impact of data breach by contracting with multiple cloud service providers and spread data stores out across all of them

C. Complement the cloud services provider’s security offerings with the healthcare organization’s use of a CASB

D. Ensure an exact copy of the data is maintained within the healthcare organization’s computing environment to prevent data loss

6. The security officer at Methodist Hospital expressed concern with a proposal to host a utilization management application serviced by a global cloud provider company. Which of these could be her valid concern?

A. PHI cannot be used by non-US personnel.

B. Global companies do not have to abide by US contracts.

C. PHI cannot be translated into foreign languages.

D. Global companies may be out of HIPAA jurisdiction.

7. The HIPAA Omnibus Final Rule specifically defines which of these?

A. Unauthorized disclosures

B. Business associates

C. Cloud providers

D. Minimum penalties

8. Moving data, including PHI, to the cloud has all of the benefits, except:

A. Transferring responsibility for security to a third party

B. Gaining specialized skillsets and certified personnel

C. Access to security tools and techniques with moderate investment

D. Professional services like vulnerability and patch management

Answers

1. C. This is the definition of operational safeguards.

2. A. For disclosures of 500 individuals or more, the covered entity is required to notify the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

3. B. Adequate bandwidth is a concern, but it is not applicable to HIPAA requirements.

4. B. HIPAA as written in 1996 has had several updates over the years, called amendments. The most recent is the HIPAA Omnibus Final Rule, which went into effect in September of 2013.

5. C. Of the choices, using a cloud access security broker (CASB) is a great approach to maintaining the required level of information security controls on the cloud (outsourced) environment.

6. D. One of the several concerns with off-shoring PHI to international third parties is the fact that they are likely not subject to U.S. law, including HIPAA.

7. B. The HIPAA Omnibus Final Rule of 2013 has a dramatic, important feature. It clearly identifies that anyone performing services subject to HIPAA law on behalf of a covered entity is a business associate. This significantly reduced any confusion from third parties who had any action in handling PHI for the covered entity.

8. A. Although any third-party agreement, particularly the business associate agreement, creates a shared responsibility, cloud services can never fully transfer responsibility. The covered entity remains ultimately responsible for the security of the data.

References

1. Baker, D. (2015). Trustworthy systems for safe and private. In V. Saba & K. McCormick (Eds.), Essentials of nursing informatics, sixth edition (pp. 152–154). McGraw-Hill Education.

2. Conrad, E., Misenar, S., & Feldman, J. (2016). CISSP study guide, third edition (p. 24). Syngress.

3. Harris, S., & Maymi, F. (2016). CISSP all-in-one exam guide, seventh edition. McGraw-Hill Education.

4. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). (2007, March). Security standards: Organizational, policies and procedures and documentation requirements. 45 C.F.R. 164.314 and 164.316. HIPAA Security Series. Accessed in March 2017 from https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/ocr/privacy/hipaa/administrative/securityrule/pprequirements.pdf?language=.

5. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). (2002, Dec. 3). OCR HIPAA Privacy: Incidental uses and disclosures. 45 C.F.R. 164.502(a)(1)(iii). Accessed in March 2017 from https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/ocr/privacy/hipaa/understanding/coveredentities/incidentalu%26d.pdf.

6. Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996. Pub. L. No. 104-191, 110 Stat. 1936 (August 21, 1996). Accessed in March 2017 from https://aspe.hhs.gov/report/health-insurance-portability-and-accountability-act-1996.

7. HHS. (2009, Feb. 17). HITECH Act Enforcement Interim Final Rule. Accessed in July 2016 from https://www.hhs.gov/hipaa/for-professionals/special-topics/HITECH-act-enforcement-interim-final-rule/index.html.

8. McCann, E. (2014). Group slapped with $6.8M HIPAA fine. Healthcare IT News, February 18. Accessed in July 2016 from www.healthcareitnews.com/news/group-slapped-68m-hipaa-fines.

9. Weise, E. (2015). Massive breach at health care company Anthem Inc. USA Today, February 25. Accessed in July 2016 from www.usatoday.com/story/tech/2015/02/04/health-care-anthem-hacked/22900925/.

10. Belliveau, J. (2016). Hackers access EHR data in potential healthcare data breach. HealthITSecurity, May 19. Accessed in July 2016 from http://healthitsecurity.com/news/hackers-access-ehr-data-in-potential-healthcare-data-breach.

11. Caraher, K., & LaVanway, A. H. (2011, Mar. 8). CDW healthcare elevated heart rates: EHR and IT security report. Accessed in July 2016 from www.cdwnewsroom.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/CDW-Healthcare-Elevated-Heart-Rates-EHR-and-IT-Security-Report-0311.pdf.

12. Anderson, M. (2011, Feb. 11). The costs and implications of EHR system downtime on physician practices. Whitepaper reprinted by Stratus Technologies; rights granted by AC Group. Accessed in July 2016 from www.stratus.com/assets/Costs_and_implications_of_Downtime_on_Physician_Practices.pdf.

13. Borkin, S. (2003). The HIPAA final security standards and ISO/IEC 17799 (p. 6). SANS Institute InfoSec Reading Room. Accessed in July 2016 from https://www.sans.org/reading_room/whitepapers/standards/hipaa-final-security-standards-isoiec-17799_1193.

14. National HIE Governance Forum (2013, December). Identity and access management for health information exchange (p. 3). From a report for the National eHealth Collaborative through its cooperative agreement with the Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Accessed in July 2016 from https://www.healthit.gov/sites/default/files/identitymanagementfinal.pdf.

15. Murphy, Sean P. (2015). Healthcare information security and privacy—Chapter 3: Healthcare information regulation (p. 80). McGraw-Hill Education.

16. Verizon. (2016). Verizon 2016 data breach investigations report (p. 21). Accessed in July 2016 from www.verizonenterprise.com/verizon-insights-lab/dbir/2016/.

17. HHS. (2010, July 14). Guidance on risk analysis requirements under the HIPAA Security Rule (p. 20). Accessed in March 2017 from https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/ocr/privacy/hipaa/administrative/securityrule/rafinalguidancepdf.pdf?

18. Donaldson, S. E., & Siegel, S. G. (2001). Successful software development (pp. 42–43). Prentice Hall.

19. Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat. (2004). Operational security standard: Management of information technology security (MITS). Accessed in July 2016 from https://www.tbs-sct.gc.ca/pol/doc-eng.aspx?id=12328.

20. Software Engineering Institute, Carnegie Mellon. (2006). A framework for software product line practice, version 5.0. Configuration Management. Accessed in July 2016 from www.sei.cmu.edu/productlines/frame_report/config.man.htm.

21. McGraw, D., & Hinkley, G. (2010, February). ARRA accounting of disclosures requirements: Aligning goals with emerging regulations. eHealth Initiative. Accessed on July 12, 2016, from https://www.cdt.org/files/pdfs/AccountingforDisclosures.pdf.

22. HHS. (2010, May 3). HIPAA Privacy Rule accounting of disclosures under the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health Act: Request for information. 75 Fed. Reg. 31425, 45 C.F.R. 160 and 164. Accessed in July 2016 from https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-2010-05-03/pdf/2010-10054.pdf.

23. National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST). (2013, Apr. 30). Recommended security controls for federal information systems and organizations (p. F48). SP 800-53, revision 4. Accessed in July 2016 from http://nvlpubs.nist.gov/nistpubs/SpecialPublications/NIST.SP.800-53r4.pdf.

24. Bourque, D., Gold, K., Willis, S., et al. (2013). Breach notification rule risk assessments: Applying the new breach notification standard under the HIPAA Omnibus Rule. Health eSource: American Bar Association. Accessed in July 2016 from www.americanbar.org/publications/aba_health_esource/2013-14/july/breach_notification.html.

25. HHS. (2013, January). Business associate contracts. Accessed in July 2016 from https://www.hhs.gov/hipaa/for-professionals/covered-entities/sample-business-associate-agreement-provisions/index.html.

26. FDA. (2014, September). Is the product a medical device? Accessed in July 2016 from https://www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/DeviceRegulationandGuidance/Overview/ClassifyYourDevice/ucm051512.htm.

27. Bolte, S. (2005). Cybersecurity for medical devices: Three threads intertwined. PowerPoint presentation to MedSun audio conference “Cybersecurity of Medical Devices,” April 12.

28. Weiner, J. P., Kfuri, T., Chan, K., & Fowles, J. B. (2007). “e-Iatrogenesis”: The most critical unintended consequence of CPOE and other HIT. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, 14, 387–388.

29. Hildreth, E. A. (1965). The significance of iatrogenesis. JAMA, 193, 386–387.

30. FDA. (2016, February). MAUDE adverse event report: Merge healthcare merge hemo programmable diagnostic computer. Accessed in July 2016 from https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfmaude/detail.cfm?mdrfoi__id=5487204.

31. Computerworld’s Forecast 2017 Survey on IT. Computerworld. Accessed on March 14, 2017 from http://core0.staticworld.net/assets/media-resource/122905/forecast_1117a.pdf.

32. Hoglund, D. (2012). Healthcare wireless and device connectivity: The BYOD Healthcare Challenge—2012. Accessed in July 2016 from http://davidhoglund.typepad.com/integra_systems_inc_david/2012/05/the-byod-healthcare-challenge-2012.html.

33. CIO Council. (2010, August). Privacy recommendations for the use of cloud computing by federal departments and agencies. Issued by Privacy Committee and Web 2.0/Cloud Computing Subcommittee. Accessed on July 12, 2016, from https://cio.gov/resources/document-library.

34. Speake, G., & Winkler, V. (2011). Securing the cloud: Cloud computer security techniques and tactics (p. 80). Elsevier.

35. Herold, R. (n.d.). Cloud computing in healthcare: Key security issues. Webinar. Accessed in July 2016 from www.bankinfosecurity.com/webinars/cloud-computing-in-healthcare-key-security-issues-w-200.

36. Winkler, V. (2011). Cloud computing: Legal and regulatory issues. TechNet Magazine. Elsevier. Accessed in July 2016 from http://technet.microsoft.com/en-us/magazine/hh994647.aspx.

37. CMS. (2007, March). Security standards: Administrative safeguards (p. 8). HIPAA Security Series. Accessed in July 2016 from https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/ocr/privacy/hipaa/administrative/securityrule/adminsafeguards.pdf.

38. U.S. Department of Defense. (2015). Information assurance workforce improvement program, December 19, 2005, incorporating Change 4, November 10, 2015. Accessed in July 2016 from www.dtic.mil/whs/directives/corres/pdf/857001m.pdf.

39. HHS. (n.d.). Audit protocol edited. Accessed in March 2017 from https://www.hhs.gov/hipaa/for-professionals/compliance-enforcement/audit/protocol-edited/index.html.

40. CMS. (2012). Shared savings program. Accessed in July 2016 from https://www.cms.gov/sharedsavingsprogram/30_Statutes_Regulations_Guidance.asp.

41. Dowell, M. (2011, May). Accountable Care organization data sharing. Health Law Alert. Accessed in March 2017 from www.hinshawlaw.com/newsroom-publications-alerts-237.html.

42. Heath, S. (2016). $1.5M HIPAA settlement fine for North Memorial Health Care. HealthITSecurity, March 17. Accessed in July 2016 from http://healthitsecurity.com/news/1.5m-hipaa-settlement-fine-for-north-memorial-health-care.

43. Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology (ONC). (2015). Guide to privacy and security of health information v2. Accessed in July 2016 from https://www.healthit.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/privacy/privacy-and-security-guide.pdf.

44. McGraw, D. (2010, Feb. 18). A good day for health privacy. Accessed in July 2016 from https://cdt.org/blog/a-good-day-for-health-privacy/.