CHAPTER 4

Healthcare Information Technology in Public Health, Emergency Preparedness, and Surveillance

J. Marc Overhage, Brian E. Dixon

In this chapter, you will learn how to

• Define population health and explain how it differs from healthcare delivery

• Describe the role of public health in managing illness outbreaks, epidemics, and pandemics

• Identify and explain issues that affect the use of data for population health

• Apply health data definitions and standards, as well as privacy and confidentiality issues, in typical public health scenarios

• Identify when public health departments can receive identifiable health information to perform public health functions without patient authorization

• Recognize and explain how population health and clinical care needs complement each other

Most people think about healthcare as being focused on the diagnosis and treatment of disease, while others perceive it to also include prevention of disease and maintenance of health and well-being. Furthermore, the notion of healthcare, especially the delivery of healthcare, is often targeted toward an individual patient. Doctors, nurses, and other healthcare professionals are often concerned with preventing, diagnosing, or treating a disease in the patient who is sitting in an exam room or lying in a hospital bed. Another, and equally important, aspect of healthcare is population health, which is focused on the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of diseases for an entire population of people rather than one individual at a time. Evolving models of healthcare delivery, such as team-based care and accountable care (see Chapters 1 and 2 for additional discussion), are focused on managing specific populations of patients, namely those who are regular consumers of healthcare at those clinics or hospitals. However, the notion of population health dates back several hundred years and is strongly associated with governmental public health departments.

Public health is concerned with preventing disease, prolonging life, and promoting health for populations. Public health departments work to prevent epidemics and spread of disease, protect against environmental hazards, prevent injuries, promote and encourage healthy behaviors, respond to disasters and assist communities in recovery, and assure the quality and accessibility of health services. These activities are generally focused on geographic populations, or the entire group of people living in a city, county, state, or nation. In the United States, local (often county) health departments provide “on the ground” services, including vaccination against communicable diseases, primary care and dental care to the uninsured population, and nutrition programs for people with diabetes or for low-income populations. The work by local health departments is supported by state health departments, who in turn are supported by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), which in turn is part of the World Health Organization (WHO). Countries other than the United States typically have governmental ministries of health that provide these services and collaborate with the CDC through the WHO.

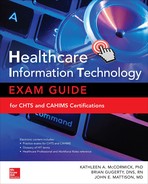

Accomplishing the core functions of essential public health services requires public health departments to monitor the health status of the population, investigate population health problems and hazards, mobilize community partners to address health problems, develop policies and plans, educate the public about health issues, and undertake various assurance activities.1 Some essential differences between clinical care and public health are depicted in Table 4-1.

Table 4-1 Differences Between Clinical Care and Public Health Perspectives

Many different people and organizations have a stake in public health, including public health practitioners (primarily those who work in public health departments in the United States), governments, employers, community groups, private payers, and, ultimately, all of us as individuals, since our health is, in part, determined by the health of others around us. Research shows that medical care and genetic factors are only responsible for about a third of a person’s health and well-being.2 Environmental and social factors, as well as behavioral choices people make, are larger determinants of health outcomes. Recent research provides evidence that a person’s ZIP code may predict health outcomes better than knowing about the person’s family history of disease or their past medical conditions.3

TIP Public health departments may provide individual patient care, but their core functions are typically focused on populations and not on individual patients.

Despite these differences, clinical care and public health interact in many ways. For example, clinical-care providers administer many immunizations that prevent communicable diseases, while public health professionals identify outbreaks of disease that may influence a provider’s choice of treatment for a patient presenting with specific symptoms. For example, a patient with fever and cough might be managed differently during an influenza outbreak than in other circumstances.4

The American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA), passed in 2009, and the Prevention and Public Health Fund, passed in 2010 as part of the Affordable Care Act (ACA), will dramatically alter the perspective on population health in the United States over the coming years. Both pieces of legislation provide significant support for initiatives focused on improving the population’s health. The ARRA, through the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health (HITECH) Act, provides funding designed to stimulate the adoption and “meaningful use” (which is being incorporated into the Advancing Care Information dimension of the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015 [MACRA]) of electronic health records (EHRs) to advance the ability of health care providers to measure the quality of care provided to populations as well as subpopulations (e.g., patients with diabetes, patients who had a stroke, etc.) and promote health information exchange (HIE), in which clinical care and public health departments can electronically share data and information about population health (see Chapter 14). The ACA, through the Prevention and Public Health Fund, provides for expanded and sustained national investment in disease prevention, wellness promotion, and public health activities. The ACA also advances the concept of accountable-care organizations (ACOs), which are provider-led organizations focused on managing the health of a population and incented to do so through new compensation models. Together these initiatives provide an opportunity to improve population health by using healthcare IT. These initiatives also create an opportunity for clinical care, ACOs, and public health departments to work together to interconnect healthcare IT systems in a way that supports optimal healthcare delivery and outcomes for populations.

Public Health Reporting

To be able to improve a population’s health, you have to be able to measure it. While a care provider might use a laboratory test and a thermometer to measure the health of an individual, measuring the health of a population requires different tools such as surveys, electronic surveillance, and statistical analysis methods. This is not as easy to do as it might sound. For example, we currently use more than 190 separate sources of data to track our progress against our national health goals as described in Healthy People 2020.5 Take something as seemingly simple as knowing how many people in a population have diabetes (the number of people with a condition divided by the number of people in the population at a single point in time is called the population prevalence) and whether this number is growing or shrinking (the number of people to get the condition over some period of time divided by the number of people in the population is called the incidence).

The traditional approach to measuring prevalence and incidence has been to carry out carefully constructed surveys of the populations. The CDC, for example, conducts a number of such surveys. Another approach is case reporting, sometimes referred to as active surveillance since it requires action on the provider’s part, in which care providers report selected data about patients who meet specified criteria for having notifiable conditions (conditions that public health departments require providers or laboratories to report under law) to public health departments that aggregate the data and track it to identify trends in conditions or procedures of interest. For example, most local health departments collect data on individuals who test positive for Lyme disease, hepatitis C, and tuberculosis (or TB). These diseases can create significant harm to both the health system with respect to cost and individuals with respect to disability and death. New cases of disease are tracked so that epidemiologists at the health department can measure the number of new cases and compare the rate of current cases to historical ones to identify if and when an outbreak may be occurring. In addition, disease investigators at health departments, often public health nurses, can contact patients with these diseases and work with community organizations (e.g., schools, day care facilities, employers) to prevent the further spread of these diseases to the people who live or work with the individuals who are sick.

Gathering information on notifiable conditions is challenging. A major challenge is that reporting disease information to departments requires busy clinic staff to fill out additional paperwork and submit it to local public health authorities. Even when providers are motivated to report about patients who have relevant conditions, they are often unaware of which conditions are reportable, don’t think about reporting while in the midst of providing care, have difficulty remembering how to report, and so on. In addition, these reports require considerable time and expense for public health departments to manage. Some reports, such as birth certificates, also require validation or certification by a health professional.

TIP Many of the case definitions provided by public health departments to guide providers on which cases to report require a diagnostic laboratory test as part of the case definition.

The use of healthcare IT in clinical care has created new opportunities for improving public health reporting. Structured and coded data captured in healthcare IT systems can be used to facilitate or automate reporting. A laboratory information system, for example, can be configured to automatically generate a report via a standards-based electronic message to departments when a result indicates a reportable condition. Similarly, information systems that receive electronic laboratory reports, or electronic messages sent by lab information systems, can be configured to automatically recognize positive test results for notifiable conditions.6 This approach to reporting, often referred to as passive surveillance because it does not require action on the provider’s part, has been shown to be faster and to identify more cases than manual reporting;7 however, the reports may be missing some of the data elements that public health departments need because the healthcare IT system doesn’t have the data. A laboratory system, for example, will not contain data about whether the patient received treatment for a specific infection and so can’t include this data in a report. Therefore, many states require both laboratories and providers to report information for notifiable conditions; these are referred to as “dual” reporting laws.

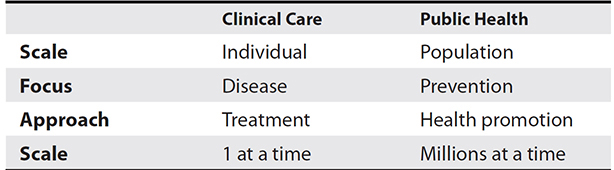

Traditionally, public health has focused on tracking conditions diagnosed by care providers, but after the anthrax exposures in 2001, interest increased in tracking potential diseases to identify natural or human-initiated outbreaks as soon as possible. This led to using data obtained prior to a diagnosis, which is an approach referred to as syndromic surveillance (Figure 4-1).

Figure 4-1 Syndromic surveillance

Syndromic surveillance refers to an approach in which evidence of an increasing number of patients with a specific set of symptoms or findings (called a syndrome) is tracked with the expectation that a developing pattern of disease will be found earlier than if public health departments waited until providers identified a diagnosis causing these symptoms. This approach might prove particularly important in cases in which an unusual underlying cause might not be recognized for days or weeks. The figure illustrates that, after an exposure, the number of patients with symptoms will climb over time and then, usually, decline. The number of patients diagnosed with the condition will follow a similar pattern but will typically lag behind the appearance of symptoms by several days.While a variety of data such as rates of absenteeism and purchase of specific over-the-counter drugs have been used in attempts to identify disease outbreaks, using this type of data is not syndromic surveillance. Syndromic surveillance is limited to the use of data collected about patients as part of their care before a diagnosis has been established.

TIP While it is sometimes possible for healthcare IT systems to determine which data are reportable to public health departments, it may not be easy. Determining whether a test result is positive (usually indicating the presence of a disease or condition), for example, can be difficult for the healthcare IT system, and in some cases it is a negative result to a test that would indicate that it should be reported.

Registries

In addition to surveillance activities in which public health departments gather data on emerging infections and track disease prevalence, many health departments also maintain population health registries. A registry is a special type of database used to collect information on a population, usually focused on a single disease, a group of related diseases, or a specific grouping of environmental contaminants. The data within registries are collected from many different sources, including insurance claims transactions, patient self-reported questionnaires or surveys, and medical record chart reviews. In addition to public health departments, other entities create and maintain registries, including research organizations, medical societies such as the American College of Cardiology, and health systems and ACOs that desire to capture additional data beyond what are in their EHR system.

Registries enable public health departments, health systems, and other organizations that use them to longitudinally follow a population over time and examine trends (e.g., Are there more people with diabetes now than ten years ago?) with respect to both care delivery (e.g., Are people with diabetes receiving annual foot exams?) and outcomes (e.g., Do individuals with high blood pressure die sooner than those with normal blood pressure?). Information from registries can be used to estimate survival rates and risks for specific diseases; to measure quality of care indicators; to evaluate short- and long-term effects of environmental exposures; and to test epidemiological hypotheses. Registries are therefore used not only in public health but also by researchers, providers (who want to look at populations they care for), and payers (who want to look at populations they insure).

The following are some common types of registries created and maintained by public health departments:

• Immunization registry Almost every state in the United State has an immunization registry that captures information on individuals who receive a vaccine, including information about the vaccine given, the provider who administered the vaccine, and the patient who received the vaccine. Just over half of U.S. states require at least one type of healthcare provider to report immunizations to the registry.8 These registries enable health departments to identify populations who are protected against vaccine-preventable diseases. The registries further provide forecasting reports to help healthcare providers, especially pediatricians, identify when a patient is due for a vaccine.

• Cancer registry These registries capture information on individuals diagnosed with cancer. Hospitals typically capture the information about patients who have a confirmed case of cancer, including information about the person diagnosed, the type of cancer, the location of cancer, and the treatment given to the patient. The data captured by hospitals are reported to state-level cancer registries, which then report final case information to the CDC and other national-level registries.

• Birth registry State health departments further require that all live births be reported to the health department. Hospitals or birthing centers capture information about the baby, the mother, and the father. This includes information about birth defects as well as other reportable conditions. The registries support both the issuance of birth certificates, which serve as legal identity documents, and surveillance of trends with respect to birth rates, infant mortality, and identification of diseases passed from mother to child.

• Death registry These registries capture the date of death and the cause of death from certified death certificates submitted by county coroners and funeral directors. The registries support epidemiological work to understand the causes of death and the risk factors associated with comorbidity. (Comorbidity is a medical condition that exists simultaneously with and usually independently of another medical condition.)

TIP Be sure that you can provide a good definition of a registry.

One component of the “meaningful use” program that incentivizes adoption of healthcare IT systems is a requirement for providers to identify and report information to specialized registries. Here are some examples of specialized registries:

• Statewide trauma registry Many states require that hospital-based emergency departments report cases of injury (e.g., injuries to the head or neck, insect bites, burns) to a registry maintained by the state public health department. These registries are used to identify causes of injury and death as well as the severity of injuries and costs of care associated with treating injuries from motor vehicle accidents, poisonings, fires, and so on.

• Birth defects registry State health departments also collect information about children to promote fetal health, prevent birth defects, and improve the quality of life for individuals living with birth defects. Data are reported on infants and young children for disorders such as autism, Down syndrome, and fetal alcohol syndrome. The registries are used to plan services for children with special health or education needs and provide resources to families.

• Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS) This is a qualified clinical data registry sponsored by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services that captures information regarding the quality of care delivered by outpatient clinicians. The registry is used to examine trends in the quality of care clinicians provide to their patients, helping to ensure that patients get the right care at the right time.

NOTE Many public health departments operate laboratories that perform specialized testing related to disease of particular public health interest. Some of this testing overlaps with tests performed in hospital laboratories, but some tests are highly specialized. You might want to incorporate data from these laboratories into a care provider’s healthcare IT system. Ideally, the test results from these laboratories would be available in a format such as the HL7 Clinical Document Architecture (CDA) using a coding system such as LOINC, which would allow them to be incorporated into healthcare IT systems.

Health Alerts

Based on their population perspective, departments will periodically have information about emerging disease outbreaks or trends that they need to communicate to healthcare providers. Examples include suggestions for providers to perform specific diagnostic testing based on patterns that public health departments are seeing in symptoms being reported. For instance, a foodborne outbreak of salmonella may prompt the health department to ask providers to test all patients they see with symptoms of diarrhea or vomiting. This allows the health department to identify the specific type of salmonella organism and track who has been affected by the outbreak. Another example might be to alert providers to specific treatment suggestions based on patterns observed across a community. For instance, awareness by the health department of drug-resistant organisms in populations treated for common diseases like skin infections may suggest that providers should consider alternative antibiotics than those to which the organisms are resistant. Most of the time, these messages or recommendations are not specific to individual patients but rather relevant to populations or groups of patients.

Public health departments maintain a system called the Health Alert Network (HAN)9 that primarily supports alerting between public health departments. In addition to publication and outreach through postings in relevant settings (for example, emergency departments), today public health departments may use a variety of mechanisms to reach individual providers, including mail, facsimile, or e-mail. In addition, there may be benefits to creating reminders within healthcare IT systems that providers use while caring for patients in order to alert them under specific conditions. This is sometimes referred to as public health decision support. This might be particularly helpful when public health departments suggest structured data that would be helpful to collect for patients who meet specified criteria or when it would be helpful for providers to order a specific kind of diagnostic test to provide more information on the cause of disease. While some demonstrations of this type of capability have been carried out,10 only limited healthcare IT systems have the ability to incorporate these types of alerts. Alerts from public health departments are not always well received by providers, because the alerts are sometimes perceived as not being relevant to their practice; other reasons that the alerts may be unwanted are limitations to scalability and targeting and alert fatigue.

Privacy and Security

Preserving the privacy and confidentiality of patients is critical. Public health departments often provide both clinical care and public health services, and these two different functions have different privacy and security implications. When providing clinical care, public health departments are considered covered entities under the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) and are subject to the same rules and requirements as other care providers. When providing public health services, different rules and requirements apply.

To enable public health departments to monitor the population’s health, HIPAA provides exceptions for covered entities, including care providers, to disclose protected health information to public health departments without patient authorization when the data are required or permitted by federal, state, or tribal statutes. These exceptions include the prevention and control of diseases, injuries, or disabilities; vital events such as deaths and births; issues to support public health surveillance; epidemiological investigations and interventions; and information sent to a foreign government agency that is collaborating with a public health department (to investigate a disease outbreak, for example). There are also exceptions for the disclosure of data about people at risk for contracting or spreading a disease; workers’ compensation and workplace medical surveillance; health oversight; instances of child abuse and neglect; domestic violence; neglect of the elderly or incapacitated; and data on adverse events, for product tracking, to facilitate product recalls or replacement and post-marketing surveillance reporting to pharmaceutical or device manufacturers. In cases of domestic violence, HIPAA additionally requires the covered entity to either seek agreement of the victim or make a determination that reporting is necessary to prevent serious harm to the individual or other potential victims.

TIP Public health departments are not covered entities under HIPAA. In some cases, parts of their activities such as direct provision of clinical care are subject to the same privacy and security rules.

In certain limited cases such as disease surveillance, a limited data set might suffice, and covered entities might be more comfortable reporting data in this fashion. In other cases, aggregated data such as a count of the number of influenza cases seen in an emergency department in a 24-hour period might suffice. Aggregated data better protect patient confidentiality than a limited data set but can be difficult to validate and can make it much more difficult to obtain additional details about a case should they be needed. Approaches have been developed that rely on assigning an arbitrary identifier that allows the provider to link to the individual patient’s data to overcome some of these limitations.

TIP While HIPAA grants broad exceptions that allow covered entities to disclose protected health information to public health departments, covered entities are frequently cautious and seek clear assurances that they are allowed to make these disclosures. This is particularly true when the disclosures involve conditions or data that might not traditionally have been perceived as relevant to public health.

Scope of Data

Public health functions may require almost any of the types of data that are required for clinical care, including diagnoses, laboratory results, radiographic results, medications, and vital signs. The scope of data that public health departments might require is significantly driven by performing syndromic surveillance and the need to investigate outbreaks. In addition to these ubiquitous types of data, public health applications often benefit from geographic location data. Such data are often useful in tracking the spread of disease but are available only in limited form (usually restricted to knowing the patient’s home address) in most traditional healthcare IT systems. Geolocation data are increasingly available through devices such as patients’ mobile phones, but these data are not yet routinely captured in healthcare IT systems.

TIP Healthcare IT systems used by providers often identify providers by using one or more IDs, and the messages they typically exchange don’t include details such as name or phone number. If these messages are repurposed for use by public health departments, the specific provider information will often need to be added to the message.

Clinical Information Standards

In general, uses of healthcare IT for public health rely on the same clinical data standards as other uses of healthcare IT. The same terminology standards, including LOINC, ICD-10, and RxNORM, are applicable. In some cases, population health applications have driven the development of relevant standards such as CVX, a code set used to identify the vaccines administered and reported to immunization registries.11 Another example is the International Classification of Disease (ICD), which was first developed, and continues to be maintained, by the WHO to standardize how countries report causes of death. Similarly, population health uses common, shared message format standards, including HL7. As for other applications of healthcare IT, public health has some unique use cases for which there are specific implementation guides that specify details appropriate to them that are different than for other use cases. Examples of use cases for which there are implementation guides specific to public health include reporting vaccinations and reportable conditions.

Public health is also unique in its use of value sets, which are subsets of terms drawn from a standardized vocabulary that apply to a given use case.12 A good example is the Reportable Conditions Mapping Table (RCMT). The RCMT is a value set published by CDC that includes the specific LOINC and SNOMED CT terms that represent reportable conditions that providers report to public health departments. The RCMT includes, for example, the various kinds of lab tests for Lyme disease along with the SNOMED CT terms assigned to various genetic variants of the microorganisms that cause Lyme disease. The CDC publishes a variety of value sets for public health use cases, including terms used by providers for reporting to cancer registries, terms associated with healthcare-acquired infections, and terms for use when reporting to immunization registries.

Because departments often receive data from multiple care providers, they may have to match patients across those providers in order to avoid double counting when estimating the incidence or prevalence of conditions. They would typically employ the same approaches to patient matching as providers use in a master patient index within or between care providers.

Trends and What to Expect in the Future

Looking forward, there are a number of ways that healthcare IT is likely to evolve to better support public health. For example, you can expect that even more information will flow from providers to public health departments to meet compliance with the meaningful use and evolving Advancing Care Information programs incentivizing adoption of EHR systems. Consequently, as public health departments become more aware of emerging disease trends, more information about community health will flow to providers in the context of care, such as enabling EHR systems to access a patient’s lifelong vaccination history and provide decision support about missing vaccinations. Similarly, the evolving need for collaboration between members of a patient’s care team will increasingly necessitate public health department communication electronically with clinical-care providers about population health events.

Methods for monitoring population health are undergoing a transformation as well. They are transforming from field-based and descriptive to clinical, analytical, and experimental. Whereas previously public health professionals would physically gather data from patients, hospitals, and clinics via paper chart review, increasingly public health departments seek access to new data sources, including EHR systems but also newer sources including social media, mobile phone applications, and over-the-counter medication sales data. For example, some health departments are using Yelp! restaurant review data to identify and track disease outbreaks,13 while other health agencies are using Twitter to identify seasonal flu outbreaks.14 This evolution underway in public health will require increased access to data about individuals in the population as well as additional data about the environment in which they live and the system in which they receive healthcare. In 2015, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation initiated a call to create a Culture in Health where clinical and public health departments could work together to address the social determinants of health. While there are some communities experimenting with combining data on social determinants, including education, criminal activity, and poverty, with data from EHR systems to better understand the underlying causes of disease and disability,15 the capacity for doing this is absent in many communities. Together, through the creation of interoperable networks of healthcare IT systems, it may one day be possible to more fully understand and intervene to improve the social, behavioral, and environmental determinants of health in addition to the genetic and health system causes of disease and poor health.

Chapter Review

Public health and clinical care are complementary processes. The types of data required to manage both are the same, but the context and purpose of data use are different. Whereas public health focuses on monitoring and intervening in the health of populations, clinical care focuses on caring for one patient at a time. Data generated by providers in the course of clinical care, such as diagnoses, medication prescribed, immunizations administered, and laboratory test results, can be very useful for public health use cases, and HIPAA provides specific exemptions that allow covered entities to share specific types of data with public health departments. Data transmission and coding standards are essentially the same for public health applications, though there are specific implementation guides tailored to accommodate aggregated data across a population rather than data on a single patient. Public health departments use data primarily to measure the prevalence and incidence of diseases in populations. Laboratory results generated by public health departments may be available to incorporate into healthcare IT and used by clinical-care providers, and you can expect that additional summary data and suggested clinical actions generated by public health departments will be pushed into providers’ healthcare IT systems in the future.

Questions

To test your comprehension of the chapter, answer the following questions and then check your answers against the list of correct answers at the end of the chapter.

1. Which types of information systems are relevant to public health informatics?

A. Immunization registries

B. Cancer registries

C. Electronic medical records

D. All of the above

2. Who is responsible for creating and implementing regulations relevant to public health?

A. Multiple agencies in federal, state, and local governments as well as some territories

B. The Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology (ONC)

C. The Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation (ASPE) in the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS)

D. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)

3. In the United States, responsibility for collecting and sharing data on population health is distributed at what organizational level(s)?

A. Federal (e.g., CDC)

B. State and territorial

C. Local (e.g., county and city health departments)

D. Federal, state, and local

4. Which of the following activities are designed to simplify data collection and public health department reporting for clinical practitioners?

A. The efforts of the ONC and CMS under ACA and MACRA to stimulate adoption of electronic medical records and health information exchange

B. HIPAA rules that prohibit sharing data for public health purposes so no activities are allowed

C. Neither of the above

D. Both of the above

5. Which of the following is true regarding clinical information standards that have been adopted to facilitate sharing of data between clinical-care providers and public health departments?

A. LOINC codes for clinical observations and the HL7 Clinical Document Architecture have been adopted.

B. The United States has yet to adopt clinical information standards to facilitate sharing between clinical-care providers and public health departments.

C. All standards being developed are for acute care hospital environments.

D. All of the above.

6. Why do clinicians often fail to report disease cases to public health departments?

A. Clinicians must take time to fill out paperwork for which they are not reimbursed, and are unaware that certain diseases need to be reported to health authorities.

B. Electronic medical record systems are not connected to the Internet, preventing transmission.

C. There are no requirements to report diseases to public health agencies.

D. All of the above.

7. In syndromic surveillance, public health departments capture which type(s) of data from healthcare providers electronically?

A. Diagnostic codes representing the diseases affecting patients seen by the providers

B. Symptoms or prediagnostic data representing reasons why the patient visited the providers

C. Laboratory results representing confirmed diseases in patients who visit the providers

D. Statistical data from hospitals on the number of patients who come in with signs of the flu

Answers

1. D. Understanding and improving the public’s health depends on interoperability between clinical information systems such as electronic medical records, public health laboratory information systems, and public health-related registries.

2. A. The essential governmental role in public health is guided and implemented by a variety of federal, state/territorial, and local regulations and laws as well as federal, state/territorial, and local governmental public health departments.

3. D. Responsibility for data collection and sharing in public health is shared by federal, state, and local health departments.

4. A. By providing subsidies, guidelines, and other incentives for adoption of EMRs and implementation of health information exchange (HIE), the federal government through CMS and the ONC is making it easier for clinical providers to adopt healthcare IT based on clinical information standards that will facilitate reporting data for public health purposes.

5. A. Several standards for terminologies (e.g., LOINC) and transport (e.g., HL7 CDA) have been adopted to facilitate exchange of information between clinical-care providers and public health departments.

6. A. Clinicians are not always trained to know which diseases need to be reported, and there are few incentives for clinicians to report disease cases other than satisfaction in knowing they are contributing to the common good.

7. B. Syndromic surveillance focuses on prediagnostic data, sometimes referred to as “chief complaints,” to provide preclinical diagnoses of specific diseases to inform monitoring of overall trends.

References

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2013). The public health system and the 10 essential public health services. In National Public Health Performance Standards. Accessed on June 10, 2016, from www.cdc.gov/nphpsp/essentialServices.html.

2. Braveman, P., & Gottlieb, L. (2014). The social determinants of health: It’s time to consider the causes of the causes. Public Health Reports, 129(Suppl 2), 19–31.

3. Cooper, R. A., Cooper, M. A., McGinley, E. L., Fan, X., & Rosenthal, J. T. (2012). Poverty, wealth, and health care utilization: A geographic assessment. Journal of Urban Health, 89(5), 828–847.

4. Gibson, J. D., Richards, J., Srinivasan, A., & Block, D. E. (2015). Public health practice applications. In V. K. Saba & K. A. McCormick (Eds.), Essentials of nursing informatics, sixth edition. McGraw-Hill.

5. CDC. (2011). Healthy people 2020. Accessed on August 8, 2016, from www.cdc.gov/nchs/healthy_people/hp2020.htm.

6. Dixon, B. E., Grannis, S. J., & Revere, D. (2013). Measuring the impact of a health information exchange intervention on provider-based notifiable disease reporting using mixed methods: A study protocol. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making, 13(1), 121.

7. Dixon, B. E., Siegel, J. A., Oemig, T. V., & Grannis, S. J. (2013). Electronic health information quality challenges and interventions to improve public health surveillance data and practice. Public Health Reports, 128(6), 546–553.

8. Martin, D. W., Lowery, N. E., Brand, B., Gold, R., & Horlick, G. (2015). Immunization information systems: A decade of progress in law and policy. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice, 21(3), 296–303.

9. CDC. (2016). Health Alert Network (HAN). Accessed on August 8, 2016, from http://emergency.cdc.gov/han/.

10. Dixon, B. E., Gamache, R. E., & Grannis, S. J. (2013). Towards public health decision support: A systematic review of bidirectional communication approaches. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, 20(3), 577–583.

11. CDC. (2016). IIS: Current HL7 standard code set CVX—vaccines administered. Accessed on August 8, 2016, from www2a.cdc.gov/vaccines/iis/iisstandards/vaccines.asp?rpt=cvx.

12. Alyea, J. M., Dixon, B. E., Bowie, J., & Kanter, A. S. (2016). Standardizing health-care data across an enterprise. In B. E. Dixon (Ed.), Health information exchange: Navigating and managing a network of health information systems (pp. 137–148). Academic Press.

13. Schomberg, J. P., Haimson, O. L., Hayes, G. R., & Anton-Culver, H. (2016, March 29). Supplementing public health inspection via social media. PLOS ONE, 11(3), e0152117.

14. Signorini, A., Segre, A. M., & Polgreen, P. M. (2011). The use of Twitter to track levels of disease activity and public concern in the U.S. during the influenza A H1N1 pandemic. PLOS ONE, 6(5), e19467.

15. Comer, K. F., Grannis, S., Dixon, B. E., Bodenhamer, D. J., & Wiehe, S. E. (2011). Incorporating geospatial capacity within clinical data systems to address social determinants of health. Public Health Reports, 126(Suppl 3), 54–61.