CHAPTER 18

Effective Organizational Communication for Large-Scale Healthcare Information Technology Initiatives

Liz Johnson

In this chapter, you will learn how to

• Describe the importance of communications in the healthcare IT initiatives

• Define the essential role of the customers

• Identify the components of the communications plan

• Understand the roles of federal agencies and federal regulations

• Discuss the role of social medial and mobile devices

In America’s twenty-first-century healthcare system, landmark federal reform legislation enacted since 2009 has served to progressively modernize care-delivery organizations with enhanced healthcare information technologies (healthcare IT) that began with the widespread adoption of electronic health records (EHRs). Most notable of these laws are the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) and its Health Information Technology and Economic and Clinical Health (HITECH) Act provision, which established the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) EHR Incentive Programs (known as Meaningful Use and often abbreviated to MU) to encourage the meaningful use of EHRs.1 These programs, one for Medicare providers and one for Medicaid providers, earmarked billions of dollars in incentive payments for eligible physicians and healthcare providers who successfully meet increasingly stringent requirements for EHR adoption and use. The incentive payments began in May 2011, and in early 2016, CMS reported that over $35 billion had been paid to more than 513,000 healthcare providers.2

However, the journey to successful integration of healthcare IT by providers industry-wide has been fraught with challenges. Tremendous complexities exist throughout healthcare organizations working on healthcare IT reform initiatives, and these complexities create a critical need for effective communication campaigns that run throughout the life cycle of acquiring, implementing, adopting, and continuously optimizing the use of EHRs in both inpatient and ambulatory settings. Efforts such as these, with effective communication programs in place as a core strategy, continue to support the six aims for improvement in care-delivery quality set forth by the Institute of Medicine in 2001: make it safe, equitable, effective, patient-centered, timely, and efficient.3

Without such communication strategies, success is far less likely. Stories of EHR implementation failures began to hit the mainstream media in the late 1990s. In 2002, for example, a major West Coast academic medical center invested heavily in the implementation of computerized provider order entry (CPOE) and encountered significant physician resistance. In large part, the clinician unwillingness to use CPOE occurred because physicians had been insufficiently informed about and inadequately trained in the use of the clinical decision support (CDS) tool being implemented.4 Stories like these continue today. According to Charles et al., “The success of the adoption and implementation of a CPOE system in urban hospitals depends on teamwork among medical staff, clinical support services, and the hospital administration.”5 Although there are any number of obstacles to a successful EHR/CPOE implementation, three are the most challenging and typically overlooked or minimally addressed: lack of communication, lack of training, and lack of use of a standard terminology. To ensure and maintain a successful implementation after go-live, there will be a repeating cycle of user optimization and technical improvements throughout the life of the system, requiring embedded programs that support communication, training, and standard terminology development.6

Numerous provider organizations have encountered similar challenges with healthcare IT implementations over the past decade.7, 8 Such costly, high-risk experiences—especially in an increasingly patient-centric healthcare industry—have underscored the importance of effective, cross-enterprise, patient-focused communications plans and strategies that include physicians and clinicians, administrators, IT professionals, and the C-suite—all of whom play critical roles as new technologies are introduced. As a result, effective communication programs are now a high priority for hospitals and physician practices as they continue to adopt and optimize the use of EHR, CPOE, and similar broadly impactful HIT systems throughout the industry.

The purpose of this chapter is to provide an overview of communication strategies that have proven effective in driving the implementation of EHRs to support the needs of patients, physicians, and the caregiver workforce. The chapter covers the importance of communications in healthcare IT initiatives, the customers and players, components of the communications plan, and industry considerations (roles of federal agencies, federal regulations, and the burgeoning role of mobile applications, social media, and health information exchange).

Importance of Communications in Health IT Initiatives

Rouse noted that healthcare organizations exist as complex adaptive systems with nonlinear relationships, independent and intelligent agents, and system fragmentation.9 While variation among them is diminishing through increasing standardization of practices and systems geared toward patient care continuity, many provider cultures still struggle with decentralization and reliance on disparate legacy systems.10 As with other industries, consolidation among acute and ambulatory providers has also helped drive standardization. As organizations across the nation continue on the journey of implementing, adopting, and optimizing the use of EHRs in the inpatient and ambulatory settings, effective enterprise-wide communications plans, which include both strategic and tactical elements, are essential. This section provides insight on the importance of communications in healthcare IT programs: in governance, the structure of a governance model, and rules for governance efforts. Specific governance models and success factors are also addressed in Chapter 20.

Leadership and Governance

The introduction of EHRs in healthcare organizations has driven transformational change in clinical and administrative workflows,11 organizational structure (i.e., that which exists among physicians, nurses, and administrators),12 and relationships among the frontline workers, physicians, administrators, and patients. Understanding the risks posed by the disruptive facets of organizational and process change is critical to ensuring the effectiveness of all healthcare IT programs, including the continued implementation, adoption, and optimization of EHRs. Vital to mitigating risks of failure is strong physician leadership and management support.13 An essential element of risk mitigation in care-delivery reform through healthcare IT is the planning and implementing of organizational communication initiatives that help to achieve the aims of an enterprise-wide governance team.

To succeed, responsibilities for such communication initiatives should be shared between health system leaders, champions, and those charged with oversight of the implementation of healthcare IT systems, all of whom have a role to play in governance structures whose processes are grounded in a strong communications strategy. Morrissey summarized the importance of such an approach for transforming healthcare organizations: “This IT governance function, guided from the top but carried out by sometimes hundreds of clinical and operations representatives, will be evermore crucial to managing the escalation of IT in healthcare delivery….” In fact, without such an informed governance process, he states, “IT at many hospitals and health care systems is a haphazard endeavor that typically results in late, over-budget projects and, ultimately, many disparate systems that don’t function well together.”14

Accountability begins at the care delivery level and rises through the enterprise level. Messaging—through electronic, in-person, or video media—from chief executive officers and board members solidifies the importance of enterprise-level healthcare IT projects.15 However, both governance structures and the communications that support them require tailoring depending on the nature of every health system.

Governance models in healthcare organizations provide a structure that engages stakeholders to work through critical decisions and ensure that risks associated with changes in policy, technology, and workflow are mitigated to maintain or improve the quality of patient care. A strong example of such a working model is provided by my own health system, Tenet Healthcare Corporation, where I serve as Chief Information Officer, Acute Care Hospitals and Applied Clinical Informatics (ACI). Tenet’s nationwide, multiyear EHR implementation program, directed by my office, was labeled IMPACT: Improving Patient Care through Technology. The mission of IMPACT, to implement a system-wide EHR and patient health record (PHR) system for all Tenet facilities and patients by 2015 while ensuring staff and physician adoption of the system throughout the process, was one of the largest and most successful projects of its kind in the nation.

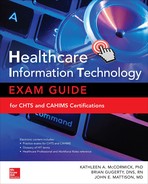

Tenet is one of the largest integrated healthcare delivery systems in the United States, employing more than 130,000 in over 80 hospitals across the country. Figure 18-1 illustrates the structure of Tenet Healthcare’s IMPACT program and the importance of communications as it was built into the implementation of the IMPACT EHR system.

Figure 18-1 EHR implementation and oversight governance

A key to the success of Tenet’s IMPACT governance was a three-tiered organizational structure that engaged the corporation, regional operations, and the hospitals themselves in a coordinated effort. Another key success factor was early commitment to key roles, including clinical informaticists, physician champions, training and communications leads, and healthcare IT leads. Binding the program together with unified, shared, and consistent messaging was a foundational strategy that supported all aspects of IMPACT’s execution.16

Hoehn summed up the importance of communications in governance: “Today, clinical IT is finally being universally viewed as a critical component of healthcare reform, and we are only going to get one chance to do this right,” she wrote. “This means having everyone in the organization, from the Board Members to the bedside clinicians, all focused on the same plan, the same tactical initiatives, and the same outcomes.”17

Rules for Governance

Effective governance committees require a solid set of rules, since hospitals are matrixed organizations composed of multidisciplinary staff and leaders from across a healthcare organization. Morrissey provides the following set of “rules to live by” for governing IT:14

1. Hardwire the committees

2. Set clear levels of successive authority

3. Do real work every time

4. Form no governance before its time

5. Put someone in charge who can take a stand

The following describes each success factor:

1. Hardwire the committees. Ensure that the chairs of lower-level committees participate at the next level in the committee structure and hierarchy. Their role is to bring forward recommendations and issues to the higher-level committee, including issues needing resolution from a higher authority, as well as issues to be communicated from the higher committee down. “A structure with unconnected levels of governance will break down.”14

2. Set clear levels of successive authority. Committee responsibilities should be well defined so members know issues they can address and issues beyond their level of authority.17 To avoid having most decisions forwarded to the uppermost level, each committee needs a well-defined set of criteria to determine which decisions they can and can’t make at that level.

3. Do real work every time. Focus meetings on important issues in need of clinician engagement. Setting an agenda and sharing it prior to the meeting helps facilitate consistent decision making. If there are no critical items, cancel the meeting and send out status reports electronically.

4. Form no governance before its time. Recognize that different organizations will not be prepared to embrace a governance structure at the same time or to the same degree as others.

5. Put someone in charge who can take a stand. The leader of the top committee must be someone who commands respect and possesses operational authority to enact recommendations.

Focus on Customers and Players

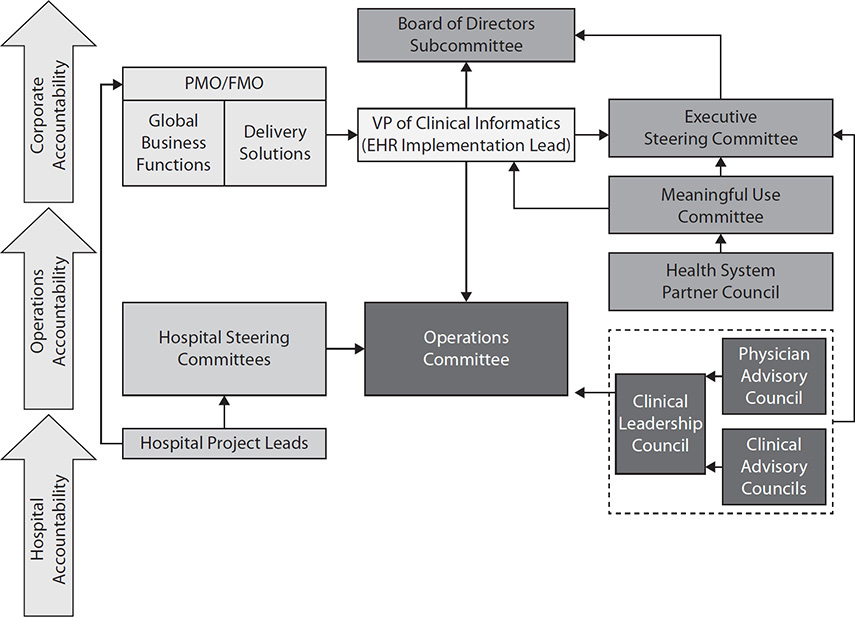

Those who are engaged in EHR implementation initiatives should also be involved in communications associated with these multiyear programs. Figure 18-2 illustrates the spectrum of customers and players.

Figure 18-2 Focus of communications

In the provider setting, each of these groups will have a different type of communications engagement. The media and vehicles used may be different, but the strategic focus is the same: improving the quality of patient care through strategic adoption and ongoing user optimization of healthcare IT that is in turn enabled by smart communications. To be effective, multiple communication approaches may be required.

Patients and Communities

In its 2001 report “Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century,” the Institute of Medicine established the need for patient-centered communications and support as part of the six aims for improving healthcare, as noted in the introduction to this chapter.18 Since then, patient-centric healthcare and the emergence of care-delivery models such as the patient-centered medical home (PCMH) have become central to healthcare reform. Integral to the PCMH concept are seven joint principles, established in 2007, one of which calls for a “whole-person orientation.” This means each personal physician is expected to provide for all of a patient’s lifetime health service needs,19 which drives the requirement for comprehensive physician-to-patient communications and shared decision making.

Such communication is also required to support healthcare reform at the community level, as demonstrated in CMS’s 2011 establishment of the Three Part Aim for the Medicare Shared Savings Program (e.g., Medicare ACO) with its focus on “better care for individuals and better health for populations.”20 In its final rule for the Medicare ACO, CMS mandated the requirement for advancing patient-centered care through accountable-care organizations (ACOs), stating “an ACO shall adopt a focus on patient-centeredness that is promoted by the governing body and integrated into practice by leadership and management working with the organization’s health care teams.”21

Physicians

As discussed in the introduction of this chapter, no adoption of EHRs by health systems or practices would have succeeded without the endorsement and ownership of the physician community. Change has been and continues to be a constant in healthcare, and physicians in particular continue to experience substantial shifts to their working environment and long-established workflows. When included from the outset of any healthcare IT transformation initiative, “physician champions” are powerful and effective communicators, assisting colleagues through healthcare IT adoption. The Office of the National Coordinator for Health IT (ONC), through its regional extension centers, had started recruiting “physician champions” who were meaningful users of EHRs to help others in their area get over the hurdles of digitizing their medical records.22 Some organizations use formal and informal processes and tools to identify more influential physicians in the organization and determine their overall attitudes toward the project. Those with strong opinions both for and against are deemed “highly influential” and need to be engaged by project leaders in different ways,

Communication that supports not only ongoing training initiatives and the management of ever-changing procedural requirements but also an understanding of the dynamics of legislated healthcare reform itself is needed through all stages of healthcare IT adoption and user optimization.23 However, such need often continues to be unmet. For example, a survey of more than 250 hospitals and healthcare systems demonstrated that significant percentages of respondent physicians had inadequate understanding of the EHR Incentive Programs (meaningful use) requirements; others cited a lack of training and change-management issues.24 The findings of this survey highlight the need to directly engage physicians in healthcare IT implementations, adoption, and user-optimization programs through comprehensive communication initiatives.

Nursing Workforce

For patients in both inpatient and ambulatory settings, nurses constitute the front line of patient care. But for health systems everywhere, they are also on the front line of healthcare IT reform. “Nurses are the biggest users of the EHR and are responsible for a large portion of the documentation that addresses quality measures, safety measures and the overall clinical picture of the patient,” said Patricia Sengstack, former president of the American Nursing Informatics Association and CNIO at Bon Secours Health System.”25 As with their physician colleagues, therefore, the role of communication is not limited to the continued training of nurses in the use of EHR systems but rather extends to fully engaging them in the ongoing design, testing, implementation, and user optimization of EHRs to support improved care coordination, continuity of care, and quality measurement. Throughout the healthcare industry, health systems’ chief information officers (CIOs) have found that the success of large health IT projects and programs depends not only on the willingness of floor nurses to accept enhanced technology, but also on the strength of the IS-nursing management connection.26 Therefore, ongoing and consistent communication with the nursing community, key for both nurse champions and nurse users of healthcare IT, is a strategic necessity.

Engagement of nursing in the process has been a part of the IMPACT program at Tenet since its inception. IMPACT’s Nursing Advisory Team (NAT) functions as a decision-making body, and NAT’s decisions became the standard for the implementation of core clinical EHR applications. How these leaders communicated their decisions proved to be integral to promoting safe, quality patient care and improving outcomes for patients and families while supporting the Tenet Clinical Quality initiatives and the standards associated with the IMPACT Program itself.16

IT Departments and Multidisciplinary Project Teams

IT departments and project teams are responsible for meeting the challenges of new-system introductions as well as managing the continuous upgrades to existing ones. To support this work, their roles in communication efforts will involve engaging clinicians in staff positions, confirming commitments, managing change, and setting EHR deployment and revision update strategies.27 It is also critical to recognize that Health Information Management, Laboratory, Pharmacy, and other ancillary departments are essential to the overall successful adoption of an EHR. Inclusion of these disciplines in communication efforts, governance, and other activities will significantly improve chances for success.

Use Case 18-1: The IMPACT Insider

Many organizations use internal newsletters as a communication tool to engage the variety of project stakeholders. First published in May 2010, The IMPACT Insider, Tenet’s weekly, cross-enterprise e-newsletter for the IMPACT program, is used to continuously inform the health system’s employees on the acute care hospital EHR implementation progress by highlighting events at the local levels, as well as providing insight into federal government drivers that may impact the EHR design and workflow standards. The IMPACT Insider of March 2016 contains information on the Interoperability Pledge, which was introduced by Health and Human Services Secretary Sylvia Burwell and signed by Tenet earlier in the year. This pledge was introduced to unite EHR providers and leading health systems with the goal of making it easier for patients to use the information in their EHRs.28

Healthcare System Leadership

As noted in the earlier section “Leadership and Governance,” communication led by an executive-level steering committee, often chaired by a health system’s CEO or COO, represents both the beginning and the end of successful healthcare IT implementation processes. Senior leadership not only establishes the size of the investment the organization is prepared to make but also communicates “the broad strategy for IT in advancing business goals and, ultimately, acting on the result of a consistently applied proposal and prioritization regimen.”14

Components of a Communications Plan

Kaiser Permanente (KP) noted in its 2011 HIMSS Davies Enterprise Award application for its KP HealthConnect EHR that its “national communications plan established positioning, messages, and strategies to create awareness, build knowledge, manage expectations, motivate end users, and build proficiency.”29 As part of its communications plans, KP included vehicles such as a central intranet site, leadership messaging, weekly e-newsletters, regional communication tactics, and videos. Other health systems also employ e-mail updates, end-user training, superusers who function as subject matter experts, and champions to secure buy-in for system adoption.

A 2013 primer from the National Learning Consortium (NLC) entitled Change Management in EHR Implementation30 offers other ideas for a communications plan, such as

• Vendor demonstrations, videos

• Role playing

• Simulated question/answer (Q/A) communication

• Staff visits to practices that have had successful EHR implementations

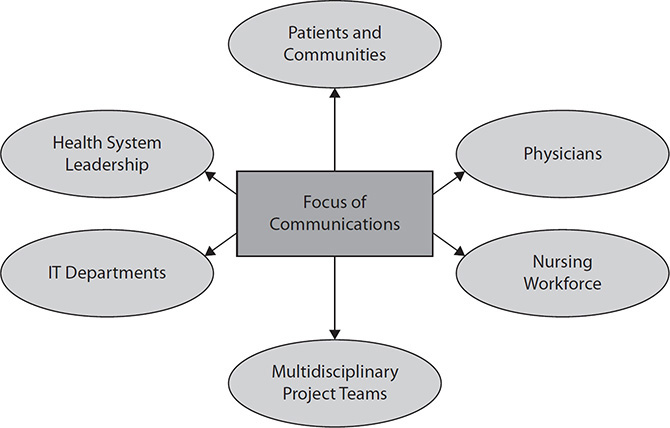

Another perspective is provided by a 2005 JHIM article by Detlev Smaltz, PhD, FHIMSS, and his colleagues, in which they discuss the importance of project communications plans focused on stakeholder groups and meeting their needs. Table 18-1 provides a sample of this plan for three stakeholder groups.31

Table 18-1 Sample of Healthcare IT Project Communications Plan

Project Phases and the Communication Functions

Healthcare IT projects and programs often unfold over multiyear periods with the following four major phases:32

• Pre-adoption (selection)

• Pre-implementation (planning)

• Implementation (go-live)

• Post-implementation (outcomes, adoption, and ongoing optimization)

Therefore, it is important that communications plans be built and integrated within these phases, because the information needs of stakeholders will vary as projects evolve and mature. Furthermore, a variety of formal and informal communications media will be needed to reach different health-system groups, a point made in a 2009 Journal of AHIMA article entitled “Planning Organizational Transition to ICD-10-CM/PCS.”33 The article further states that because points of urgency and risks to be mitigated are also critical to key stakeholders, they should also be considered among the key elements of an effective communication strategy.

Communication Metrics

The best metrics to measure communication program effectiveness are arguably the same used to present the stories of successful healthcare IT projects and programs themselves. As is the case with Tenet Healthcare, a large nationwide independent delivery network (IDN), strong governance programs supported by a pervasive and adaptable communications strategy helped to drive 49 successful EHR go-lives from early 2011 to 2015. This success continues as new hospitals are added to the Tenet portfolio. These results were and continue to be supported by the Tenet e-newsletter The IMPACT Insider; local hospital site-specific communication campaigns; future state workflow localization; change readiness assessments; at-the-elbow support for providers from superusers and subject matter experts throughout the go-live processes; physician partnering; post go-live support; and 24/7 command centers for ten days post go-live.

Key Industry Considerations

While the focus of much of the communication supporting the implementation, adoption, and user optimization of new EHR systems and related healthcare IT programs and projects is directed inside an individual health system, those who are responsible for building communication strategies must do so in the context of industry change beyond the traditional four walls of a health system. With the arrival and rapid entrenchment of the digital age over the past two decades, inclusion of mobile devices and social media platforms has expanded, enriching communications options to support successful healthcare IT integration and information interoperability. Furthermore, the actions of the federal government to ensure secure health information interoperability constantly redefine how and what the healthcare industry can expect to communicate across the continuum of care. Therefore, communications planning in support of healthcare IT initiatives must continue to reflect the forces driving such change: an expanding world of media, the roles of federal healthcare agencies, and the adoption of regulatory standards as they continue to drive the evolution of the interoperability of health information.

The Expanding World of Media

Physicians and clinicians across the industry are now regularly communicating among themselves and with their patients through the use of social media and mobile health device technology. In a recent Black Book Market Research survey of 6,000 physicians, greater than half of the responders reported they use their mobile devices to reference data at work or view patient records.34 Such technologies have continued to improve and clinicians now rely heavily on them to document patient visits, manage clinical workflows, conduct research on technical and clinical issues, and receive alerts regarding patient conditions.

While the upside to this continued rapid increase in communication technologies is tremendous, the deployment of such devices in the marketplace has outpaced the ability for most organizations to maintain safety and security. As reported by the Brookings Institution in May 2016, 23 percent of all data breaches happen in the healthcare industry. Over the past six years, health records of more than 155 million Americans have potentially been exposed in 1,500 separate breaches—the per-record cost of which is $363, the highest of all industries.35

Beyond devices, digital media vehicles encompass a multitude of healthcare-specific social media web sites, which bring new opportunities to improve provider-to-provider communications with physician-centric channels. In a 2015 Forbes Advisor Network interview, Dr. Kevin Campbell, an internationally recognized cardiologist, explained that he uses social media to communicate with patients, communicate with physician colleagues, interact with scientists across the world, educate himself and others, and share ideas.36

As with mobile devices, the many positive effects to be gained from participation in social media must be considered alongside concerns for the privacy and security of protected health information (PHI). Supported by the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) Privacy and Security Rules passed in 1996, healthcare organizations have become more vigilant in establishing rules and policies governing participation in social media. Such heightened awareness was noted in the April 2012 Federation of State Medical Board’s Model Guidelines for the Appropriate Use of Social Media and Social Networking in Medical Practice.37 Even so, as these communication platforms continue to evolve, addressing issues of privacy and security will continue to be a primary concern for the industry, physicians, health systems, patients, and the healthcare reform movement as a whole.

Role of Federal Healthcare Agencies

Healthcare reform during the past decade has been defined, spearheaded, and guided by federal government agencies armed with ARRA and HITECH legislation in providing funding, oversight, and industry-level guidance on the implementation and adoption of healthcare IT throughout the United States.38 Leading the government’s healthcare initiatives is the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS).39

For HIT purposes, two key divisions of HHS are CMS and the ONC, both introduced earlier. In addition to Medicare (the federal health insurance program for seniors) and Medicaid (the federal needs-based program), CMS oversees the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), HIPAA, and the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA), among other services. Also, under HITECH, CMS was charged with advancing healthcare IT through implementing the EHR Incentive Programs, helping define meaningful use of EHR technology, drafting standards for the certification of EHR technology, and updating health information privacy and security regulations under HIPAA.40

The ONC and two critically important federal advisory committees operating under its auspices have had considerable influence on healthcare IT development and implementation the past seven years. The first of those committees is the Health IT Policy Committee, which makes recommendations to ONC on development and adoption of a nationwide health information infrastructure, including guidance on what standards for interoperability of patient medical information will be required.41 The second is the Health IT Standards Committee, which focuses on recommendations from CMS, ONC, and the Health IT Policy Committee on standards, implementation specifications, and certification criteria for the electronic exchange and use of patient health information (PHI).42

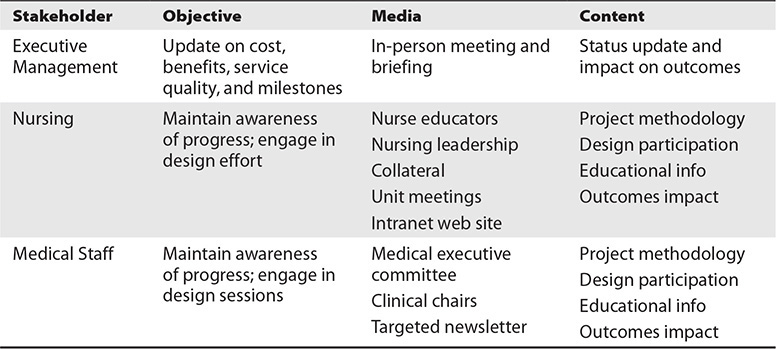

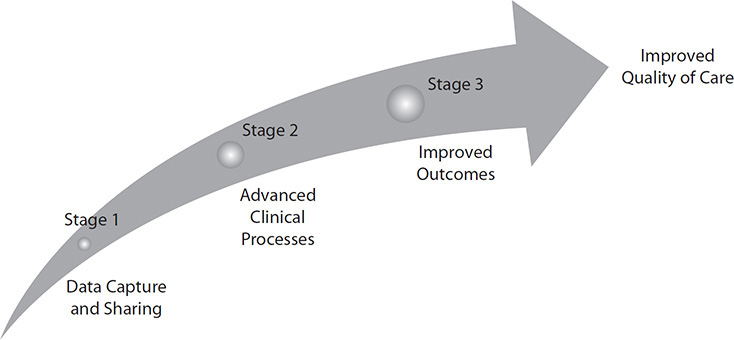

Understanding the roles of these agencies and committees—and keeping abreast of their actions—is an important responsibility for those engaged in planning and delivering communications that support healthcare IT adoption. Individually and collectively, they continue to help drive the definition of incentive payment requirements across the three stages of EHR meaningful use. Each stage has created new healthcare IT performance requirements for a given health system. These requirements also define the kinds of information exchange and interoperability required between healthcare entities across the entire continuum of care, including those directly focused on the patient and the community. Figure 18-3 provides a snapshot of each stage’s objectives:

Figure 18-3 Three stages of EHR meaningful use

• Stage 1 Beginning in 2011 as the EHR Incentive Programs’ starting point for all providers, stage 1 meaningful use consisted of transferring the collection of data to EHRs and being able to share information, such as electronic visit summaries for patients.

• Stage 2 Stage 2 meaningful use includes additional standards such as online access for patients to their health information and electronic health information exchange between providers.

• Stage 3 Stage 3 meaningful use, which is optional for participating providers to attest to in 2017 and mandatory for all but a few special classes of providers to attest to in 2018 and beyond, is defined to include demonstrating that the quality of healthcare has been improved.43

Consistent with the ever-changing healthcare and healthcare IT landscape, new programs and proposed rules focused on healthcare reform continue to be introduced to revamp payment approaches for healthcare services. In the past, providers were incented based on the volume of services provided, with a small percentage tied to quality metrics. The new incentives are shifting primarily to the quality of care given, with potential financial penalties for care that is deemed unnecessary. This new approach is sometimes referred to as “value versus volume.” An example of this is the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015 (MACRA) and the implementation of the Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS). In testimony before the Senate Finance Committee in July of 2016, Andrew Slavitt, Acting Administrator for CMS, said the MACRA reforms aim to replace a “patchwork of programs,” in which he included the Medicare EHR Incentive Programs (meaningful use), and modernize Medicare and simplify quality programs as well as payments for physicians.44 Given the IT implications of programs such as these, their impact and complexity warrant attention and should be included as part of the overall communications plan.

Role of Regulatory Standards and the Evolution of Health Information Exchange

In today’s era of healthcare reform, numerous standards in the area of health, health information, and communications technologies help to guide our industry toward interoperability between independent entities and systems. The goal is to support the safe, secure, and private exchange of PHI in ever-increasing volumes to improve the quality of care.

As advised by ONC, CMS, and the HIT Policy Committee, the HIT Standards Committee is the primary federal advisory committee working to fulfill this mandate. It is also a committee upon which I have proudly been serving since 2009 at the appointment of then HHS Secretary Kathleen Sebelius. The following list summarizes the duties of this committee under ARRA:45

• Harmonize or update standards for uniform and consistent implementation of standards and specifications

• Conduct pilot testing of standards and specifications by the National Institute of Standards and Technology

• Ensure consistency with existing standards

• Provide a forum for stakeholders to engage in development of standards and implementation specifications

• Establish an annual schedule to assess recommendations of HIT Policy Committee

• Conduct public hearings for public input

• Consider recommendations and comments from the National Committee on Vital and Health Statistics (NCVHS) in development of standards

The HIT Standards Committee established over the course of its deliberations a number of important workgroups as subcommittees to the parent committee. These workgroups met periodically to discuss their topics, present their findings at HIT Standards Committee meetings, and make recommendations to the HIT Standards Committee. Specific areas of focus of the subcommittees included clinical operations, clinical quality, privacy and security, implementation, vocabularies, and a variety of other subject areas that fall under what ONC and CMS called the Power Team Summer Camp.46 Although the HIT Standards Committee and other ONC advisory groups are undergoing reorganization at the time of this writing, these important areas of focus are likely to be carried on.

Communications resulting from the work of the various subcommittees are critical for ensuring that current regulations and notices of proposed rulemaking (NPRM) are brought into the public arena. As an example, the Implementation Workgroup, which is dedicated to ensuring that what is being asked of the greater health-system and physician-practice communities is actually feasible in terms of adoption and meaningful use, employs extensive communication tools. A strong public communications strategy is core to the work of this group, which holds hearings with broad healthcare industry representation (including health systems, physicians, and EHR and other healthcare IT vendors and developers, among others) and maintains active liaison relationships with the sister HIT Policy Committee. As a result, the Implementation Workgroup will continue to bring forward “real-world” implementation experience into the Standards Committee recommendations with special emphasis on strategies to accelerate the adoption of proposed standards (or mitigate barriers, if any).47

All HIT Policy and Standards Committees and related workgroup meetings are held in public with the notices for each meeting posted on the ONC web site and in the Federal Register.48 Public comments are always welcome.

Chapter Review

ARRA, HITECH, and the EHR Incentive Programs have helped the healthcare industry make a paradigm shift in care delivery through the accelerated use of healthcare IT. CMS, ONC, and its HIT Policy and Standards Committees continue to drive communications at the industry level to provide all stakeholders with a common set of rules to follow for selection, design, implementation, and adoption of EHRs. Challenges still persist, however, when effective communications plans are not developed and followed in complex healthcare IT programs and projects that can affect physicians, nurses, administrators, and patients alike.

This chapter has addressed issues regarding the importance of communications and the development of effective communication strategies in strengthening initiatives ranging from governance efforts to physician-to-patient partnerships—all as part of successful EHR implementations and ongoing user optimization. Key takeaways from this chapter include

• Coordinated, cross-enterprise communications strategies are critically important parts of healthcare IT programs and projects, including the development of governance structures supporting the implementation, adoption, and ongoing user optimization of EHR systems.

• The customers and players engaged in communications include patients and communities, physicians, nurses, project teams and IT departments, and health system leadership. Remember that a patient-centered focus, consideration of the EHR meaningful use program, and physician and nurse engagement are all critical factors in the communication initiatives for these participants.

• Vehicles in a communications plan can include an intranet, use of FAQ documents and interactive “Ask a Question” links, print media, road shows, town hall meetings, and standard meetings, all of which can be used through all phases of a project. The success of such projects is frequently the best measure of the communications plan’s effectiveness.

• Some of the most powerful forces driving change include the use of social media platforms, use of mobile devices, and continued complex healthcare reforms requiring portability and interoperability of patient information.

• The committees of ONC, the HIT Policy and Standards Committees, and subcommittees such as the Implementation Workgroup are key drivers of national communications important to all stakeholders involved in working toward the meaningful use of EHRs.

• Tenet Healthcare’s IMPACT EHR program, with its governance structure and effective communications efforts, serves as one example for healthcare IT program communications.

As the healthcare industry grows increasingly interconnected through healthcare IT and other technologies, effective communications plans will remain essential parts of the process. With a commitment to the development and execution of communications strategies around the continued implementation, adoption, and user optimization of emerging healthcare IT, higher levels of ownership and commitment by professionals will help to ensure the success of the U.S. healthcare reform movement in years to come.

Questions

To test your comprehension of the chapter, answer the following questions and then check your answers against the list of correct answers at the end of this section.

1. Effective communication programs support the goal of achieving the Institute of Medicine’s six aims for improvement in quality care delivery. Which of the following is not one of the six aims?

A. Effective

B. Safe

C. Noteworthy

D. Equitable

2. What caused the lack of clinician adoption and resistance toward use of CPOE in 2001 at a major West Coast academic medical center?

A. Insufficient funding

B. Insufficient information and inadequate training on clinical decision support tools

C. Lack of leadership

D. Poor implementation

3. What is a key to the success of Tenet’s IMPACT governance model (used as a governance example model)?

A. Uses a three-tiered organizational structure

B. Uses a bottom-up approach

C. Engages multidisciplinary staff

D. Uses technology effectively

4. What is not one of the “rules to live by for” governance committees article?

A. Hardwire the committees.

B. Set clear levels of successive authority.

C. Form no governance before its time.

D. Have concise committee meeting agendas.

5. Who did the ONC regional extension centers recruit to help others get over the hurdles of digitizing their medical records?

A. Physician champions

B. Nurse executives

C. Industry researchers

D. Hospital CEOs

6. Which of the following does the National Learning Consortium’s Change Management in EHR Implementation primer suggest including in a communications plan?

A. Vendor demonstrations, videos

B. Role playing

C. Simulated question/answer (Q/A) communication

D. Staff visits to practices that have had successful EHR implementations

E. All of the above

7. With the arrival of the digital age, innovations in ______________ have enriched communications options to support successful healthcare IT integration.

A. Speech communications

B. Transportation services

C. Mobile devices and social media

D. Fiber-optic cable

8. Which subcommittee of the HIT Standards Committee was dedicated to ensuring that what is being asked of the greater health-system and physician-practice communities is actually feasible in terms of adoption and meaningful use?

A. Operations

B. Strategic Planning

C. Public Relations

D. Implementation

Answers

1. C. In the Institute of Medicine’s 2001 seminal report, “Crossing the Quality Chasm: A Health System for the 21st Century,” six aims for improving the quality of healthcare were identified as safe, equitable, effective, patient-centered, timely, and efficient.

2. B. A well-known West Coast academic medical center experienced significant resistance to its CPOE implementation because it provided insufficient information and inadequate training on CDS tools, and this proved to serve as a strong lesson-learned case example for the industry on the importance of effective communication on CPOE and EHR implementation projects.

3. A. Tenet Healthcare’s governance model engages the corporation, regional operations, and their hospitals in a coordinated effort as part of the three-tiered organizational structure.

4. D. While having well-planned meetings is important, it was not one of the “rules to live by” for governance committees. Options A, B, and C were part of the rules to live by, along with putting someone in charge who can take a stand and doing real work every time.

5. A. Regional extension centers recruited physician champions to serve as role models and share best practices and lessons learned in becoming meaningful users of EHRs.

6. E. NLC’s Change Management in EHR Implementation offers these ideas and more for including in a communications plan.

7. C. These two types of innovations have strengthened communication options, increasing the success of EHRs and other healthcare IT.

8. D. Out of six subcommittees of the ONC-HIT Standards Committee, the Implementation subcommittee has a strong public communications strategy and maintains an active liaison role with the HIT Policy Committee.

References

1. Blumenthal, D., & Tavenner, M. (2010). The “meaningful use” regulation for electronic health records. New England Journal of Medicine, 363(6), 501–504.

2. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). (2016). EHR incentive programs: Data and program reports. Accessed on February 26, 2017, from https://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-guidance/legislation/EHRIncentivePrograms/DataAndReports.html.

3. Institute of Medicine, Committee on Quality of Healthcare in America. (2001). Executive summary. In Crossing the quality chasm: A new health system for the 21st century (pp. 5–6). National Academies Press.

4. Bass, A. (2003, June 1). Health-care IT: A big rollout bust. CIO Magazine. Accessed on July 17, 2016, from www.cio.com/article/2442013/infrastructure/health-care-it--a-big-rollout-bust.html.

5. Charles, K., Cannon, M., Hall, R., & Coustasse, A. (2014). Can utilizing a computerized provider order entry (CPOE) system prevent hospital medical errors and adverse drug events? Perspectives in Health Information Management. Accessed on February 27, 2017, from http://perspectives.ahima.org/can-utilizing-a-computerized-provider-order-entry-cpoe-system-prevent-hospital-medical-errors-and-adverse-drug-events/#.

6. Vaidya, A. (n.d.). Five healthcare leaders discuss the challenges of EMR adoption, implementation. Accessed on May 2, 2016, from www.beckershospitalreview.com/healthcare-information-technology/5-healthcare-leaders-discuss-the-challenges-of-emr-adoption-implementation.html.

7. Shortliffe, E. H. (2005). Strategic action in health information technology: Why the obvious has taken so long. Health Affairs, 24(5), 1222–1233.

8. Baron, R. J., Fabens, E. L., Schiffman, M., & Wolf, E. (2005). Electronic health records: Just around the corner? Or over the cliff? Annals of Internal Medicine, 143(3), 222–226.

9. Rouse, W. (2008). Healthcare as a complex adaptive system: Implications for design and management. Bridge, 38(1).

10. Kaplan, B., & Harris-Salamone, K. D. (2009). Health IT success and failure: Recommendations from literature and an AMIA workshop. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, 16(3), 291–299.

11. Campbell, E. M., Sittig, D. F., Ash, J. S., Guappone, K. P., & Dykstra, R. H. (2006). Types of unintended consequences related to computerized provider order entry. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, 13(5), 547–556.

12. Bartos, C. E., Butler, B. S., Penrod, L. E., Fridsma, D. B., & Crowley, R. S. (2008). Negative CPOE attitudes correlate with diminished power in the workplace. AMIA Annual Symposium Proceedings 6, 36–40.

13. Ash, J. S., Anderson, J. G., Gorman, P. N., Zielstorff, R. D., Norcross, N., Pettit, J., & Yao, P. (2000). Managing change: Analysis of a hypothetical case. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, 7(2), 125–134.

14. Morrissey, J. (2012, February). iGovernance. Hospitals and Health Networks Magazine. Accessed on July 17, 2016, from www.hhnmag.com/articles/6008-igovernance.

15. College of Healthcare Information Management Executives (CHIME). (2010). Chapter 9: Communication dispels fear surrounding the EHR conversion. In The CIO’s guide to implementing EHRs in the HITECH era. CHIME Report.

16. Johnson, E. O. (2012, Apr. 10). IMPACT journey program briefing. Tenet Healthcare Corporation internal corporate briefing.

17. Hoehn, B. J. (2010). Clinical information technology governance. Journal of Healthcare Information Management, 24(2), 13–14.

18. Institute of Medicine, Committee on Quality of Healthcare in America. (2001). Chapter 2: Improving the 21st century healthcare system, patient-centeredness. In Crossing the quality chasm: A new health system for the 21st century (pp. 48–50). National Academies Press.

19. Patient-Centered Primary Care Collaborative. (2007). Joint principles of the patient-centered medical home. Accessed on July 17, 2016, from www.pcpcc.net/content/joint-principles-patient-centered-medical-home.

20. Overview and Intent of Medicare Shared Savings Program, 76 Fed. Reg. 67,804 (Nov. 2, 2011), I(C).

21. Processes to Promote Evidence-Based Medicine, Patient Engagement, Reporting, Coordination of Care, and Demonstrating Patient-Centeredness, 76 Fed. Reg. 67,827 (Nov. 2, 2011), II(B)(5).

22. Mosquera, M. (2011, Mar. 4). “Physician champions” help other docs with EHR adoption. Government HealthIT. Accessed on July 17, 2016, from www.govhealthit.com/news/physician-champions-help-other-docs-ehr-adoption.

23. Scher, D. L. (2014, Oct. 25). Five reasons why physician champions are needed. Accessed on May 2, 2016, from www.kevinmd.com/blog/2014/10/5-reasons-physician-champions-needed.html.

24. National Latino Alliance on Health Information Technology (LISA). (2012, Apr. 25). Providers make progress in EHR adoption, challenges remain. iHealthBeat. Accessed on July 17, 2016, from https://listahit.wordpress.com/2012/04/25/providers-make-progress-in-ehr-adoption-challenges-remain-by-miliard-healthcare-it-news/.

25. Herman, B. (2014, Nov. 1). Nurse CIOs are taking on bigger roles in healthcare. Modern Healthcare. Accessed on July 17, 2016, from www.modernhealthcare.com/article/20141101/MAGAZINE/311019980.

26. Mitchell, M. B. (2012, Feb. 21). Role of the CNIO in nursing optimization of the electronic medical record (EMR). HIMSS (Health Information Management Systems Society) 2012 Annual Conference Presentation.

27. CHIME. (2010). Chapter 3: Assessing the organization’s current state in IT, charting a new course; Chapter 7: Considering new role players for your EHR implementation. In The CIO’s guide to implementing EHRs in the HITECH era (pp. 13, 31). CHIME Report.

28. Tenet Healthcare Corporation. (2016, Mar. 18). Tenet, ACI play leading roles in National Patient Safety Week. IMPACT Insider: Acute Care Hospital Implementation News.

29. Health Information Management Systems Society (HIMSS). (2011). Davies Enterprise Award for Kaiser Permanente: Management section (p. 5). Accessed on February 27, 2017, from http://s3.amazonaws.com/rdcms-himss/files/production/public/2011%20Davies%20Full%20App_final_11072011_additional%20info.pdf.

30. HealthIT.gov. (2013, Apr. 30). Change management in EHR implementation: Primer. Accessed on May 2, 2016, from https://www.healthit.gov/sites/default/files/tools/nlc_changemanagementprimer.pdf.

31. Smaltz, D. H., Callander, R., Turner, M., Kennamer, G., Wurtz, H., Bowen, A., & Waldrum, M. R. (2005). Making sausage: Effective management of enterprise-wide clinical IT projects. Journal of Healthcare Information Management, 19(2), 48–55.

32. Rodríguez, C., & Pozzebon, M. (2011). Understanding managerial behavior during initial steps of a clinical information system adoption. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making 11, 42.

33. D’Amato, C., D’Andrea, R., Bronnert, J., Cook, J., Foley, M., Garret, G., …Yoder, M. J. (2009). Planning organizational transition to ICD-10-CM/PCS. Journal of AHIMA, 80(10), 72–77.

34. Wike, K. (2015, Aug. 20). More than half of physicians use mobile to access patient data. Accessed on May 5, 2016, from www.healthitoutcomes.com/doc/more-than-half-of-physicians-use-mobile-to-access-patient-data-0001.

35. Miliard, M. (2016, May 5). Brookings calls out OCR on HIPAA audits, offers security. Accessed on May 5, 2016, from https://www.healthcareitnews.com/news/brookings-calls-out-ocr-hipaa-audits-offers-security-tips-healthcare-organizations.

36. Belbey, J. (2015, Sept. 24). Can doctors improve patient outcomes with social media? Accessed on May 3, 2016, from www.forbes.com/sites/joannabelbey/2015/09/24/can-doctors-improve-patient-outcomes-with-social-media/.

37. Federation of State Medical Boards (FSMB). (April, 2012). Model guidelines for the appropriate use of social media and social networking in medical practice. Accessed on May 10, 2016, from www.fsmb.org/Media/Default/PDF/FSMB/Advocacy/pub-social-media-guidelines.pdf.

38. Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF). (2009). Chapter 4: Recent federal initiatives in health information technology. In Health information technology in the United States: On the cusp of change. Accessed on July 17, 2016, from www.rwjf.org/pr/product.jsp?id=50308.

39. Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. (n.d.). HealthyPeople2020: Health communications and health information technology. HealthyPeople.gov. Accessed on July 17, 2016, from www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topicsobjectives2020/overview.aspx?topicid=18.

40. CMS. (n.d.). SearchHealthIT. Accessed on July 17, 2016, from http://searchhealthit.techtarget.com/definition/Centers-for-Medicare-Medicaid-Services-CMS.

41. Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology (ONC-HIT). (n.d.). Health IT Policy Committee. Accessed on July 17, 2016, from https://www.healthit.gov/facas/health-it-policy-committee.

42. ONC-HIT. (n.d.). Health IT Standards Committee. Accessed on July 17, 2016, from https://www.healthit.gov/facas/health-it-standards-committee.

43. CMS. (n.d.). Fact sheet: EHR incentive programs in 2015 and beyond. Accessed on July 17, 2016, from www.cms.gov/Newsroom/MediaReleaseDatabase/Fact-sheets/2015-Fact-sheets-items/2015-10-06-2.html.

44. Bazzoli, F. (2016, July 14). Support swells for flexibility in implementing MACRA. HealthData Management. Accessed on July 17, 2016, from www.healthdatamanagement.com/news/support-swells-for-flexibility-in-implementing-macra?tag=00000151-16d0-def7-a1db-97f0366e0000.

45. RWJF. (2009, May). Chapter 4: Recent federal initiatives in health information technology. In Health information technology in the United States: On the cusp of change, 2009; American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, H. R. 1, 111th Cong., § 3003(b), HIT Standards Committee, Duties.

46. Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology (ONC). (n.d.). HIT Standards Committee Workgroups. Accessed on July 17, 2016, from https://www.healthit.gov/FACAS/health-it-standards-committee/HITSC-Workgroups.

47. ONC. (n.d.). Implementation Workgroup. Accessed on July 17, 2016, from https://www.healthit.gov/facas/health-it-standards-committee/hitsc-workgroups/implementation.

48. ONC. (n.d.). Upcoming Health IT Standards Committee meetings. Accessed on July 17, 2016, from https://www.healthit.gov/FACAS/meetings/25.