CHAPTER 17

The Electronic Health Record as Evidence

Kimberly A. Baldwin-Stried Reich

In this chapter, you will learn how to

• Discuss the sources and structure of law within the United States and federal agencies that provide oversight of the nation’s healthcare system, including the laws, rules, and regulations governing healthcare delivery

• Examine the importance of privacy and security of health information in regulatory investigations and the admissibility of electronic health records into a court of law

• Delineate the differences between federal, state, and local courts

• Describe the process of the discovery of the electronic health record and ensuring its admissibility as evidence into a court of law

• Explore the role that technology plays as the underpinning of the nation’s healthcare information infrastructure

• Explain the impact the 2016 HIPAA access rules are having on the release of information and definition of the legal health record

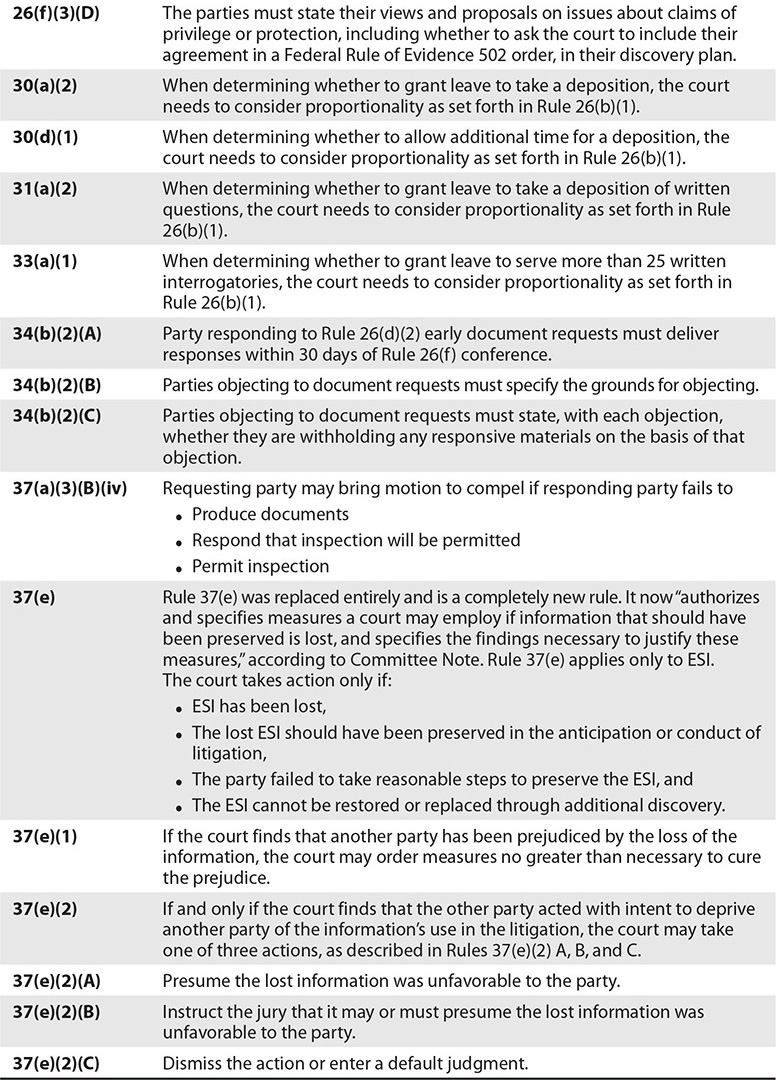

• Review the 2015 amendments to the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure and the 2016 amendments to the Federal Rules of Evidence and understand their impact on the process of electronic discovery of the EHR and its production in a court of law

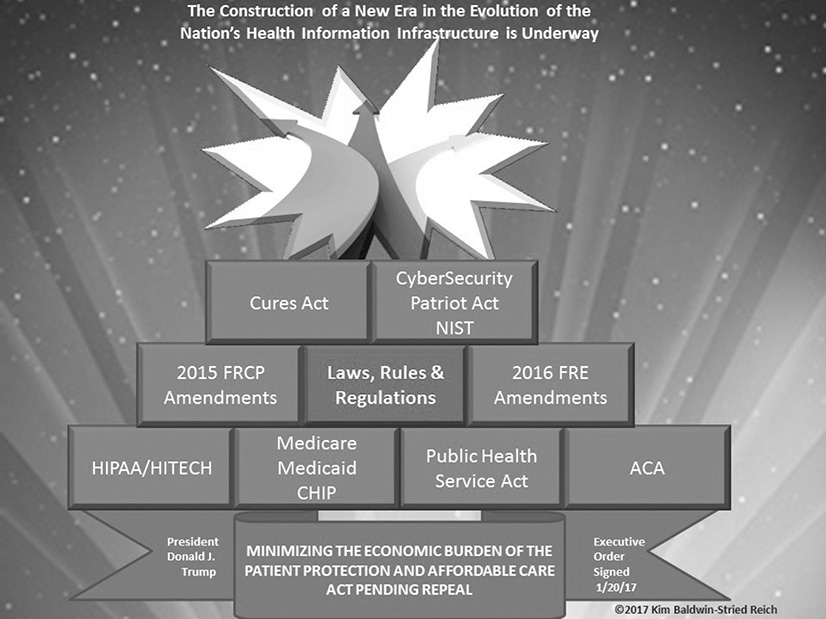

This chapter explores the primary role the electronic health record (EHR) plays in support of direct and indirect patient care activities and the secondary role it serves as evidence in legal, administrative, investigative, and regulatory proceedings. This chapter examines the legislative process and the federal agencies that oversee the nation’s healthcare system and promulgate the laws that serve as the underpinning of the nation’s health information infrastructure. It also examines the evidentiary impact of the 2015 amendments to the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure (FRCP), the 2016 Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) rules, and the 2016 amendments to the Federal Rules of Evidence (FRE). Finally, this chapter anticipates the impact that the passage of the Cures Act in 2016 will have on the future of healthcare delivery and the nation’s health information infrastructure.

Sources and Structure of U.S. Law

U.S. laws establish the standards of behavior, the means by which standards are enforced, and the mechanism to guide conduct. There are four primary sources of law within the U.S. legal system:

• Federal and state constitutions

• Federal and state statutes

• Decisions and rules of administrative agencies

• Decisions of the court

In this chapter we discuss the sources and structure of U.S. law to understand how each branch of the U.S. government operates. We examine how the branches of government work together to provide oversight of the nation’s healthcare system, as well as to establish the laws, rules, and regulations that govern the nation’s healthcare delivery system, including the admissibility of the EHR as evidence into a court of law. Through this appraisal of the legal system and overview of the structure and function of the federal government, we gain a better understanding of how the Constitution underpins all branches of government and serves as the ultimate source of law.

Three Branches of U.S. Government Responsible for Carrying Out Government Powers and Functions

The healthcare industry is one of the most (if not the most) highly regulated industries in the United States today. As such, it is important to understand the structure of the federal government, how laws are created, and the role the government plays in oversight and enforcement of the laws, rules, and regulations that impact the nation’s healthcare delivery system. A law is defined as “any system of regulations to govern the conduct of the people of a community, society, or nation, in response to the need for regularity, consistency, and justice based upon collective human experience.”1 A regulation is defined as “a rule of order having the force of law, prescribed by a superior or competent authority, relating to the actions of those under the authority’s control.”2

The three branches of the government—legislative, executive, and judicial—are responsible for carrying out the governmental powers and functions and creation of laws, rules, and regulations. Each of the three branches of government has a different primary function. The following is a summary of the primary functions of each of the three branches of the U.S. government:

• Legislative branch The legislative branch is the law-making branch of government, made up of the Senate, the House of Representatives, and agencies that support Congress. The primary function of the legislative branch is to enact laws.

• Executive branch The president is the head of the executive branch of the government, which includes many departments and agencies. The primary function of the executive branch is to enforce and administer the law.

• Judicial branch The judicial branch is made up of the Supreme Court, lower courts, special courts, and court support organizations. The primary function of the judicial branch is to adjudicate and resolve disputes in accordance with the law.

The three branches of government operate under a concept known as the separation of powers. Under this concept, no branch of the government shall have more power or control than the other two branches in the exercise of its functions and activities.

Executive Branch: President, Vice President, and Cabinet

Under Article II of the Constitution, the power of the executive branch is vested in the President of the United States, who also serves as head of state, leader of the federal government, and Commander in Chief of the armed forces. The president and the vice president comprise the executive branch. The president appoints the heads of the federal agencies, ambassadors, and other high-ranking officials, including members of the cabinet who also serve as members of the president’s administration. The president and the president’s administration are responsible for the execution and enforcement of the laws, rules, and regulations written by Congress. Fifteen executive departments, each led by an appointed member of the president’s cabinet, are responsible for the day-to-day administration of the federal government. They are joined in this responsibility by other executive agencies such as the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and the Department of Justice (DOJ), the heads of which are not part of the president’s cabinet but operate under the full control and authority of the president.3

The president also appoints the heads of more than 50 independent federal commissions, such as the Federal Trade Commission (FTC), and is empowered to enact special boards, commissions, or committees, such as President Bill Clinton did in 1997 when he created the President’s Advisory Commission on Consumer Protection and Quality in the Health Care Industry.4 The president also makes appointments to the Supreme Court, appointments of federal judges, appointments of ambassadors, and appointments to other federal offices. The Executive Office of the President (EOP) is composed of the immediate staff to the president, along with entities such as the Office of Management and Budget and the Office of the United States Trade Representative.

The president is vested with the power to sign legislation into law or veto bills enacted by the Congress, although Congress is vested with the power to override a presidential veto with a two-thirds vote in both the Senate and the House of Representatives. The president has broad authority to manage national affairs and establish the priorities of the government. The president also conducts diplomacy with other nations and has the power to negotiate and sign treaties. In addition the president has the power to issue rules, regulations, and instructions called executive orders,5 which have the force and effect of law by carrying out a provision of the Constitution, a federal statute, or a treaty. Executive orders are published in the Federal Register to notify the public of presidential actions.

The president has unlimited power to extend pardons and clemencies for federal crimes, except in cases of impeachment. Article II, Section 2 of the Constitution states that the president “shall have Power, by and with the Advice and Consent of the Senate, to make Treaties, provided two-thirds of the Senators present concur.” This means that two-thirds of the Senate must approve a treaty in order for it to be ratified.

Article II, Section 3 of the Constitution further stipulates that, with these powers, the president shall “from time to time give to the Congress Information of the State of the Union, and recommend to their Consideration, such Measures as he judge necessary and expedient.”6

The president has the power and duty to make recommendations to Congress that the president deems “necessary and expedient.” However, the judgment as to what a president determines as “necessary and expedient” has been argued in the courts. In the landmark opinion Youngstown Sheet & Tube Co. v. Sawyer7 (1952), the Supreme Court ruled that President Truman lacked either constitutional or statutory authority to seize the nation’s strike-bound steel mills. Instead, the court ruled that Congress would have had constitutional authority to do so.

This landmark decision is important to understand because it teaches us both about the Constitution, the role of Congress, the separation of powers doctrine, and the limits of presidential powers in issuing executive orders. Although the framers of the Constitution did not expressly enjoin the system of checks and balances of power our nation enjoys today, Youngstown demonstrates “that significant separation of powers depends on the existence of some effective counterweight to the executive ruler, which in turn presupposes a disposition to restrain the ruler that does not come from the ruler himself.”8

Legislative Branch: The Senate and the House of Representatives

Under Article I of the Constitution, the legislative branch is made up of the Senate and the House of Representatives, which together form the United States Congress. The Constitution vests the Congress with the power to enact legislation, confirm or reject presidential nominations, establish congressional investigations, and declare war.

The Senate is composed of 100 senators, two from each of the 50 states. The vice president serves as the president of the Senate and may cast the decisive vote in the event of a tie in the Senate. The Senate has the power to ratify treaties to confirm presidential appointments that require the consent of the Senate.

The House of Representatives is composed of a total of 435 elected officials, divided among the 50 states proportional to their population. In addition, there are six nonvoting members in the House of Representatives that represent the District of Columbia, the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, and four other U.S. territories. The Speaker of the House of Representatives is elected by the House of Representatives and is third in line in succession to the presidency. The House has several exclusive powers, including the power to initiate revenue bills, to impeach federal officials, and to elect the president of the United States in the event of a tie in the electoral college.

In order to pass legislation, the House of Representative and the Senate must pass the same bill by majority vote in order to send it to the president for his signature. The president has the power to veto legislation sent by the Congress, but the Congress may override a presidential veto by passing the bill again in each chamber with at least two-thirds of both bodies voting in favor of the bill.

The Legislative Process

Before a bill is signed into law, the first step it must undergo is its introduction to Congress. Anyone can write a bill, but only members of Congress can introduce legislation. The president traditionally introduces some bills, before Congress, such as the federal budget. However, after a bill is introduced to Congress, it may (and generally does) undergo drastic changes before it is signed into law.

Once a bill is introduced to Congress, it is referred to the appropriate committee for review. There are 17 Senate committees, with 70 subcommittees, and 23 House committees, with 104 subcommittees. The numbers, scope, and responsibility of the committees change with each new Congress. Each committee is responsible for the oversight of a specific policy area, and subcommittees take on more specialized policy areas or responsibilities. For example, the Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions is composed of three subcommittees: Subcommittee on Children and Families, Subcommittee on Employment and Workplace Safety, and Subcommittee on Primary Health and Retirement Safety.

The election of Donald J. Trump as the 45th President of the United States on November 8, 2016, is expected to bring about “significant legal and regulatory changes.”9 There is no greater insight into some of the significant changes that the nation is about to undertake in reforming and reshaping the nation’s healthcare delivery system than is evidenced by President Trump’s appointment to lead the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS).

On February 10, 2017, Rep. Tom Price, a retired orthopedic surgeon from Atlanta, was confirmed as Secretary of HHS. In this new role, Secretary Price will oversee the Medicare and Medicaid Programs and the National Institutes of Health, making the Department of HHS a $1 trillion agency, the largest of any budget in the president’s cabinet. Secretary Price is also expected to implement the repeal and the replacement of the Affordable Care Act. During his confirmation hearing, Rep. Price said this about health care coverage and his vision for the future:

What I commit to the American people is to keep patients at the center of health care. And what that means to me is making certain every single American has access to affordable health coverage.10

The details as to what the repeal and replacement of the Affordable Care Act will look like are unknown at this time, but it is the current administation’s stated commitment to reform the healthcare delivery system and to assure all Americans have access to affordable health care coverage.

On February 27, 2017, President Trump hosted a listening session with the CEOs of some of the nation’s largest health insurance companies. During this session President Trump appealed to the CEOs of the nation’s largest health insurance plans to work with Secretary Price to “stabilize the insurance markets and ensure a smooth transition to the new plan.”11

President Trump’s appointment to lead the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid (CMS), Seema Verma, was expected to be confirmed in early March, 2017. The CMS administrator “has the power to drive our nation’s healthcare transformation—from volume to value…and innovations in healthcare delivery and services in Medicare can set the course for the entire healthcare industry.”12

On February 28, 2017, in his first address to a joint session of Congress, President Trump reconfirmed to the nation his commitment to reshaping the nation’s healthcare delivery system by promising to replace the Affordable Care Act “with reforms that expand choice, increase access, lower costs, and at the same time, provide better healthcare.”13

In the coming months, the scope and direction of the healthcare delivery system and the laws, rules, and regulations impacting it will become clear once the president’s cabinet appointments are confirmed and the membership of Congressional committees is solidified.

Administrative Agencies

The rules and decisions set forth by administrative agencies are other sources of law. Administrative agencies are established under Article 1, Section 1 of the Constitution, which states that “[A]ll legislative Powers herein granted shall be vested in a Congress of the United States.”14 The legislature has delegated to numerous administrative agencies the power through Article 1, Section 8, Clause 18, “…to make all Laws which shall be necessary and proper for carrying into Execution the foregoing Powers, and all other Powers vested by this Constitution in the Government of the United States, or in any Department or Officer thereof.”15 A summary of the powers and authorities of the administrative agencies are outlined in the sections that follow.

The Department of Health and Human Services16 The Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) represents almost a quarter of all federal outlays. It administers more grant dollars than all other federal agencies combined. HHS’s Medicare program is the nation’s largest health insurer, handling more than 1 billion claims per year. Medicare and Medicaid together provide healthcare insurance for one in four Americans, and today with the addition of the Health Insurance Marketplace and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), at least one in three Americans receives some sort of coverage under HHS.

HHS works closely with state and local governments, and many HHS-funded services are provided at the local level by state or county agencies or through private-sector grantees. The department’s programs are administered by eleven operating divisions, including eight agencies in the U.S. Public Health Service and three human services agencies. The department includes more than 300 programs, covering a wide spectrum of activities. In addition to the services they deliver, the HHS programs provide for equitable treatment of beneficiaries nationwide and enable the collection of national health and other data.

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services17 The bill that led to the establishment of Medicare and Medicaid was signed into law on July 30, 1965, by President Lyndon B. Johnson. Formerly known as the Health Care Financing Administration (HCFA), the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) has been providing health insurance coverage for Americans since 1966. CMS operates as part of HHS and administers the Medicare, Medicaid, CHIP, and Health Insurance Marketplace.

CMS is headquartered in Baltimore, Maryland, and maintains ten Regional Offices (ROs) throughout the country based on the agency’s key lines of business: Medicare Plans Operations, Financial Management and Fee for Service Operations, Medicaid and CHIP, Quality Improvement, and Survey and Certification Operations. The ROs are the state and local presence and provide oversight, outreach, and education to beneficiaries, healthcare providers, state governments, CMS contractors, community groups, and others.

As the steward of the nation’s healthcare funds, CMS is committed to strengthening and modernizing America’s healthcare system. CMS does this by developing mechanisms to assure program integrity (reducing fraud, waste, and abuse), establishing value-based incentives to reward providers’ clinical performance, and tying provider payments to expected clinical outcomes.

The Office for Civil Rights18 The HHS Office for Civil Rights (OCR) is the federal agency designated to provide administrative oversight and enforcement of the HIPAA Privacy and Security rules. The OCR has been responsible for oversight of the HIPAA Privacy Rule since April 14, 2003, and the HIPAA Security Rule since July 27, 2009. The OCR ensures that people have equal access and opportunities to participate in certain healthcare and human services programs without unlawful discrimination.

The goals of the OCR are accomplished by

• Teaching health and social service workers about civil rights, health information privacy, and patient safety confidentiality laws

• Educating communities about civil rights and health information privacy rights

• Investigating civil rights, health information privacy, and patient safety confidentiality complaints to identify discrimination or violation of the law and take action to correct problems

The Office of the National Coordinator19 The Office of the National Coordinator for Health IT (ONC) was created in 2004 under Executive Order and was legislatively mandated in the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health (HITECH) Act of 2009. The ONC is located within the Office of the Secretary of HHS and is the federal agency responsible for coordinating nationwide efforts to implement and use healthcare information technology (healthcare IT) and to facilitate the exchange of health information. The ONC serves as a resource to the entire healthcare system and was created to support the federal government’s efforts to advance the adoption of healthcare IT.

On July 19, 2016, the ONC, OCR, and Federal Trade Commission (FTC) jointly published a report to Congress entitled Examining Oversight of the Privacy and Security of Health Data Collected by Entities Not Regulated by HIPAA.20 This groundbreaking report was developed to specifically address the oversight gaps that exist today between HIPAA covered entities that collect and process health data from individuals and those that are not regulated by HIPAA but also collect and process health data from individuals.

The health data that are collected, used, and shared by entities not currently covered by HIPAA can be valuable for clinical decision making or relevant in a court of law. As such, this report is an important first step in advancing the standards and processes surrounding the searching, preservation, collection, processing, and production of such information as evidence, whether for clinical decision-making purposes or for submission to a court of law.

At the present time, while the ONC is at the forefront of national initiatives to advance the adoption of healthcare IT, it does not have administrative oversight responsibility for the design, usability, safety, or clinical functionality of healthcare IT or information exchange systems or any of the consumer devices in use today. The ONC is solely focused on advancing the implementation of healthcare IT and exchange of health information.

The passage of the 21st Century Cures Act on December 13, 2016, also established new requirements under HIPPA which specify that a researcher’s remote access of protected health information (PHI) held within a covered entity’s EHR does not constitute the removal of the PHI from the covered entity, provided that HIPAA-compliant privacy and security safeguards are in place within the covered entity and the researcher, and the researcher does not copy or otherwise retain any PHI.21

This provision was enacted in an effort to reflect the shift from paper-based medical records to maintenance of digital records. While the Cures Act directly addresses questions posed by covered entities about remote access, further legislative or regulatory activity appears to be necessary to clarify what constitutes the “premises” of the covered entity, as many covered entities do not maintain their EHR systems via local storage (digital or otherwise) but instead rely on third-party business associates.22 In addition, the Cures Act does not provide direction as to harmonization of HIPAA and the Federal Policy for the Protection of Human Subjects (aka Common Rule) with respect to how such preparatory research activities should be structured. The Common Rule definition of research contained in 45 CFR 46.102(d) also includes “research development.” Given that definition, more rules regarding the privacy and security of PHI regarding research activities conducted by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and/or other federal agencies may be developed in the future.22

The Federal Trade Commission23 The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) conducts a variety of activities to promote competition in healthcare, including outreach and education to businesses and consumers on healthcare privacy and security practices.

The FTC enforces federal consumer protection laws that prevent fraud, deception, and unfair business practices and provides guidance to market participants—including physicians and other health professionals, hospitals and other institutional providers, pharmaceutical companies and other sellers of healthcare products, and insurers—to help them comply with the nation’s privacy and antitrust laws.

As part of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) of 2009, the FTC issued a final rule requiring certain web-based businesses to notify consumers when the security of their health information is breached. In 2010, the FTC began enforcing the HIPAA Breach Notification rule, which applies to the following entities:24

• Vendors of personal health records (PHRs)

• PHR-related entities

• Third-party service providers for vendors of PHRs or PHR-related entities

In addition, the FTC has a Mobile Health Apps Interactive Tool to help developers learn the privacy and security rules and regulations they need to follow when creating their health apps for mobile devices.25

The Food and Drug Administration26 The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has the following responsibilities:

• Protecting the public’s health by assuring that foods are safe, wholesome, sanitary, and properly labeled, and that human and veterinary drugs, vaccines, other biological products, and medical devices intended for human use are safe and effective

• Protecting the public from electronic product radiation

• Assuring that cosmetics and dietary supplements are safe and properly labeled

• Regulating tobacco products

• Advancing the public’s health by helping to speed product innovations

• Helping the public get the accurate, science-based information they need to use medicines, devices, and foods to improve their health

The FDA’s responsibilities extend to all 50 states, the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, Guam, the Virgin Islands, American Samoa, and other U.S. territories and possessions.

The Internal Revenue Service27 The Internal Revenue Service (IRS) is organized to carry out the responsibilities of the secretary of the Department of the Treasury under section 7801 of the Internal Revenue Code. The secretary has full authority to administer and enforce the internal revenue laws and has the power to create an agency to enforce these laws. The IRS was created based on this legislative grant. Section 7803 of the Internal Revenue Code provides for the appointment of a commissioner of internal revenue to administer and supervise the execution and application of the internal revenue laws.

On June 28, 2012, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled on several key issues affecting the Affordable Care Act (ACA)28 in National Federation of Independent Business, et al. v. Sebelius, et al.29 The Court ruled that the “individual mandate” to require individuals to purchase health insurance was constitutional. However, the Court also ruled as unconstitutional the provision that would permit the secretary of HHS to withdraw all of the Medicaid funding provided to a state if that state chooses not to expand Medicaid to certain thresholds set forth in the ACA.

Until recently, the IRS served as the administrative agency responsible for providing the administrative oversight and review in the collection of all taxes and penalties to be assessed on individuals who do not have health insurance in accordance with the Supreme Court decision handed down on June 28, 2012. However, on January 20, 2017, when Donald J. Trump was sworn into office, he signed an executive order aimed toward the ultimate replacement of the ACA, which reads in part:

Sec. 2….[T]he heads of all other executive departments and agencies (agencies) with authorities and responsibilities under the Act shall exercise all authority and discretion available to them to waive, defer, grant exemptions from, or delay the implementation of any provision or requirement of the Act that would impose a fiscal burden on any State or a cost, fee, tax, penalty, or regulatory burden on individuals, families, healthcare providers, health insurers, patients, recipients of healthcare services, purchasers of health insurance, or makers of medical devices, products, or medications.30

In accordance with this executive order, the IRS will no longer be responsible for the collection of taxes or penalties on individuals who do not purchase health insurance. And furthermore, this executive order also lays forth the foundation for another restructure and redesign of the nation’s healthcare system.

The Office of Inspector General31 Established in 1976, the Office of Inspector General (OIG) is part of HHS and is the largest inspector general’s office in the federal government. The OIG provides oversight of the Medicare and Medicaid programs, as well as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), NIH, and the FDA.

The vast majority of the OIG’s resources are dedicated to fighting fraud, waste, and abuse in Medicare, Medicaid, and more than 100 other HHS programs. The OIG carries out its mission through audits, investigations, and evaluations that result in cost-savings or policy recommendations for decision-makers and the public. The OIG also educates the public and the healthcare industry about fraudulent schemes, including what to look for and how to report them, and develops and distributes resources to assist the healthcare industry in their efforts to fight fraud, waste, and abuse.

The Federal Bureau of Investigation32 Established in 1908, the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) reports to both the U.S. Attorney General, who serves as the head of the Department of Justice (DOJ), and the Director of National Intelligence (DNI). The FBI maintains dual responsibilities for law enforcement and intelligence. The mission of the FBI is to protect the American citizens and uphold the U.S. Constitution.

The FBI employs over 35,000 people, working in 56 field offices located in major cities throughout the United States, 350 resident agencies located in cities and towns across the country, and more than 60 international offices located in U.S. embassies worldwide.

Combating and rooting out healthcare fraud is a high priority for the FBI because healthcare fraud impacts both the nation’s economy and the lives of American citizens. The FBI serves as the principal investigative agency involved in the fight against healthcare fraud and maintains jurisdiction over both federal and private healthcare insurance programs. Healthcare fraud investigations are an integral area of focus for the FBI, and personnel in each of the 56 field offices are specifically assigned to investigate matters involving healthcare fraud.

To promote the exchange of facts and information between the public and private sectors in an effort to reduce the prevalence of healthcare fraud, the FBI works collaboratively with other federal agencies such as the OIG, FDA, and Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA); with state and local agencies; with private insurance groups, and with public-private entities such as the Healthcare Fraud Prevention Partnership (HFPP)33 and the National Health Care Anti-Fraud Association.34

The Department of Justice35 The Judiciary Act of 1789 created the Office of the Attorney General. The Act specified that the Attorney General, originally a part-time position, must be “learned in the law,” with a duty “to prosecute and conduct all suits in the Supreme Court in which the United States shall be concerned, and to give his advice and opinion upon questions of law when required by the President of the United States, or when requested by any of the heads of the departments, touching on any matters that may concern their departments.”35

The DOJ officially came into existence on July 1, 1870, when Congress empowered it to handle all criminal prosecutions and civil suits in which the United States had an interest. In 1870, Congress also created the Office of the Solicitor General, who was charged with the responsibility of representing the United States in matters argued before the Supreme Court and to support and assist the Attorney General.

The 1870 Act was foundational to the establishment of DOJ, but over the years, with the addition of the Offices of Deputy Attorney General and Associate Attorney General and the formation of various components, offices, boards, and divisions, the DOJ has grown into the world’s largest law office and the chief enforcer of all federal laws. The DOJ plays a crucial role in the enforcement of the laws, rules, and regulations governing the healthcare delivery system. The detection and elimination of healthcare fraud and abuse is one of the top priorities of the DOJ, along with advocacy to promote competition in the healthcare industry. The Antitrust Division of the DOJ enforces the antitrust laws in healthcare to protect competition and to prevent anticompetitive conduct.

HIPAA established a national Health Care Fraud and Abuse Control Program, under the joint direction of the Attorney General and the Secretary of HHS, acting through the HHS Inspector General (HHS/OIG), designed to coordinate federal, state, and local law enforcement activities with respect to healthcare fraud and abuse. In May 2009, the Attorney General and Secretary of HSS announced the creation of the Health Care Fraud Prevention and Enforcement Action Team (HEAT), an initiative designed to enhance collaboration between the DOJ and investigative agencies, such as the FBI. With the creation of the new HEAT effort, the DOJ pledged a cabinet-level commitment to prevent and prosecute healthcare fraud.36 HEAT is composed of top-level law enforcement agents, prosecutors, attorneys, auditors, evaluators, and other staff from DOJ, HHS, and their operating divisions, and is dedicated to joint efforts across government to both prevent fraud and enforce current antifraud laws around the country.

Since its inception, HEAT has charged more than 2,300 defendants with defrauding Medicare of more than $7 billion and convicted approximately 1,800 defendants of healthcare felony fraud offenses.36 The medical record is a key source of evidence used by federal investigators to root out and convict suspects of healthcare fraud. For example, a federal jury in the Southern District of Texas convicted a Houston-based home-health agency owner for her role in a $13 million Medicare fraud and money laundering scheme.37 The home-health agency provider falsified medical records to make it appear as though the Medicare beneficiaries qualified for and received home-health services.

Judicial Branch: Structure and Function of the U.S. Court System

The U.S. court system is divided administratively into two separate systems: the federal district courts and the state courts. Each court system operates independently of the executive and legislative branches of government. The federal court system is set forth in Article III, Section 1 of the Constitution, which states that “[T]he judicial Power of the United States shall be vested in one supreme Court, and in such inferior Courts as the Congress may from time to time ordain and establish. The Judges, both of the supreme and inferior Courts, shall hold their Offices during good Behavior, and shall, at stated Times, receive for their Services, a Compensation, which shall not be diminished during their Continuance in Office.”38 While both the federal and state court systems are responsible for hearing certain types of cases, neither system is completely independent of the other, and the systems do interact on occasion.

Federal Court System39

The federal court system is composed of 94 district courts, 13 circuit courts, and one Supreme Court with at least one bench in each of the 50 states, as well as benches in Puerto Rico and the District of Columbia. A total of 1 to 20 judges preside in each district. District judges are appointed by the president and serve for life. Cases handled by federal district court include: cases involving violation of federal law and/or allegations of Constitutional violations; cases directly involving a state or federal government; maritime disputes; and/or cases involving foreign governments, citizens of foreign countries, or in which citizens of two or more different states are involved.

The courts of appeals are directly above the federal district court. The court of appeals system is composed of 13 judicial circuit courts throughout the United States, plus one court of appeals in the District of Columbia. There are a total of 6 to 27 judges in the courts of appeals. In addition to hearing appeals for their respective federal district courts, the courts of appeals also have jurisdiction to hear cases involving a challenge to an order of a federal regulatory agency.

The Supreme Court is located in Washington, D.C., and is also known as “The Highest Court in the Land.” It is the only court that is explicitly mandated by the Constitution. The Supreme Court is composed of one chief justice and eight associate justices. When there is a vacancy on the Supreme Court, the president makes a nomination for membership and the Senate confirms or rejects the nomination. Like federal judges, once confirmed, a Supreme Court justice serves for life. When the Senate is in recess, the President may make a temporary appointment, called a recess appointment, to any federal position, including the Supreme Court, without Senate approval in accordance with Article II, Section 2, Clause 3 of the Constitution. A recess appointment shall last for one year or until such time that a nomination is confirmed by the Senate. The Supreme Court hears cases from state appellate courts on federal or constitutional matters. The Supreme Court has the authority to decline to review most cases and maintains final jurisdiction over all cases it hears.

State Court System40

The state court system is large and diverse. Currently, there are more than 1,000 various types of state courts and judges. State courts, which are also referred to as local courts, include magistrate court, municipal court, justice of the peace court, police court, traffic court, and county court. These courts are called the inferior courts. The more serious cases are heard in a superior court, also sometimes known as state district court, circuit court, or by a number of other names. The majority of healthcare medical malpractice cases are heard in the state superior court system.

State superior, district, or circuit courts are generally organized by counties, hear appeals from the inferior courts, and have original jurisdiction over major civil suits and serious crimes. Most of the nation’s jury trials occur in state superior court. The highest state court is usually called the appellate court, the state court of appeals, or state Supreme Court and generally hears appeals from the state superior courts and, in some instances, has original jurisdiction over particularly important cases. A number of the larger states, such as New York, may also have intermediate appellate courts between the superior courts and the state’s highest court. Additionally, a state may also have a wide variety of special tribunals, usually on the inferior court level, including divorce court, mental health court, housing court, juvenile court, family court, small-claims court, and probate court.

The Judiciary

The fourth source of U.S. law arises from judicial decisions, also known as case law (discussed in further detail in the next section). Today, many of the legal rules and principles applied by U.S. courts are rooted in the traditional unwritten law of England, based on custom and usage known as “common law.” Today, “almost all common law has been enacted into statutes with modern variations by all the states except Louisiana, which is still influenced by the Napoleonic Code. In some states the principles of Common Law are so basic they are applied without reference to the statute.”41 In the process of deciding an individual case, the courts interpret regulations and statutes in accordance with the relevant federal or state constitution. The court will create and establish the “common law” when it decides cases that are not controlled by regulations, statutes, or a constitution.

The courts are responsible for making determinations as to whether specific regulations or statutes are in violation of the Constitution. The case of Marbury v. Madison established that all legislation and regulations must be consistent with the Constitution and that the courts hold inherent powers to declare legislation invalid when it is unconstitutional.42 Some state courts have established specific sets of rules for interpretation of conflicting regulations and statutes.

Administrative agencies also have discretion as to how regulations or statutes are applied—and disagreements over the application of a specific regulation or statute can and do arise frequently. While the decision of an administrative agency can be appealed to the courts, the courts generally defer decisions to the relevant administrative agency and will limit their review of the matter unless the following conditions were not met:

• A delegation of the matter to the administrative agency was constitutional.

• The administrative agency acted within its authority and followed proper procedures.

• The agency acted on a substantial basis and acted without discrimination or arbitrariness.

Case Law Case law is defined as “reported decisions of appeals courts and other courts which make new interpretations of the law and, therefore, can be cited as precedents. These interpretations are distinguished from ‘statutory law,’ which are the statutes and codes (laws) enacted by legislative bodies; ‘regulatory law,’ which are regulations required by agencies based on statutes; and in some states, the ‘common law,’ which is the generally accepted law carried down from England. The rulings in trials and hearings which are not appealed and not reported are not case law and, therefore, not precedent or new interpretations.”43 The term “common law” is often used interchangeably with case law.

CAUTION Avoid using the terms “common law” and “case law” interchangeably, because “common law” refers to the traditional unwritten law of England, while “case law” refers to the laws that were established by judicial decision.

The Medical Record

An individual’s health information, irrespective of its form, format (paper, EHR, EMR PHR, mHealth, telemedicine, health social media, or e-prescription), or location, contains vital clinical information to support the diagnosis and justify the care and treatment rendered to the patient. Certain information—including the patient’s history, physical examination results, radiology and laboratory reports, diagnoses and treatment plans, as well as orders and notes from doctors, nurses, and other healthcare professionals—is routinely recorded into an individual’s medical record when the individual is treated as an inpatient or an outpatient in a care facility.

EHR stands for “electronic health record” and is a computerized record system that originates and is controlled by physicians, hospitals, or clinics. EMR stands for “electronic medical record” and is a digital version of the patient’s paper chart in the clinician’s office. The EHR is viewed within the industry as the patient’s “legal medical record.” An EMR contains the medical and treatment history of the patient in one practice.44 Oftentimes, the terms EHR and EMR are used interchangeably, but the EHR is intended to refer to a much more robust health record system versus the medical record of a physician office.

The PHR stands for “personal health record” and is a computerized record system that is maintained by the patient or a patient’s caregiver or family member. The PHR is a tool that is used to collect, track, and share past and current information about a patient’s health. At this time, in the absence of legal standards for preservation data from PHI, the “PHR is separate from, and do[es] not replace, the legal record of any health care provider.”45 In today’s digital era, the fact that the PHR is not defined as a “legal record” presents a perplexing dilemma for patient care. For providers and organizations in malpractice claims, this information that may reside in a patient’s PHR or other third-party devices can be valuable and clinically relevant, yet it may or may not be shared with the provider.

mHealth stands for mobile-health. This term refers to the delivery of medicine and public health using mobile devices, including smartphones, tablet computers, and laptops.

Telemedicine is a term used to refer to the evaluation, diagnosis, and treatment of patients at a distance using telecommunications technology.

Health social media is a term that generally refers to Internet-based tools that allow individuals and communities to gather and communicate; to share information, ideas, personal messages, images, and other content; and, in some cases, to collaborate with other users in real time.

The quality and integrity of the information contained in a medical record are essential for clinical, legal, and fiscal purposes, for correct and prompt diagnosis and treatment of the patient’s condition, and for continuity of care. Therefore, all providers and entities alike should have some protocol in place to verify the authenticity and integrity of the information that is recorded into an individual’s medical record, especially information obtained from external sources, such as PHRs, mHealth, and health social media.

According to Matthew Murray, MD, Chairman of the Texas Medical Association’s Ad Hoc Committee on Health Information Technology, “Whether we’re copying and pasting information from an old note to a new note or using templates that automatically bring in clinical information…it is our responsibility to make sure that the information that got pulled is accurate.”46

In addition to assuring that the information that is pulled into the EHR is accurate, when providers or entities are presented with recordings or results from mHealth devices, PHRs, or health social media from their patients, the copies of these recordings, or notations, should be placed into the patient’s medical record. The provider receiving such information should document that the results from the mHealth device or PHR were reviewed and discussed with the patient along with the actions, or recommendations, if any, that were made. Although there are benefits to incorporating data from PHRs, mHealth devices, and health social media into the medical record, it must be noted that, at this point in time, there are also risks associated with these data.47 There is no way for providers or entities to assure the quality or integrity of data from these sources, yet providers and entities alike are now charged with a duty to review and discuss this health information with their patients when it is presented to them. Furthermore, it is distressing that because there are no standards related to the preservation of PHI data from PHRs, health social media, and other third-party devices, providers may be left unaware of the existence of valuable clinical data on these devices that may help defend them in the face of a malpractice claim.

Although the primary use of the medical record is to serve as a tool for the planning and communication of the patient’s treatment and care, it also serves as a secondary source of information for other uses. It provides support and documentation for insurance claims, legal matters, utilization review, case management, care coordination, professional quality and peer-review activities of prescribed treatments and medications, and the education and training of health professionals. Medical records also contain useful statistical and research information for public health and resource-management planning purposes. They contain data for clinical studies, evaluation and management of the costs associated with treatment, and the assessment of population health.

Medical records also often serve as a vital piece of evidence in a court of law.48 Today, with the widespread adoption of electronic health records, attorneys and providers now find themselves struggling to verify the accuracy and make sense of all the information contained in today’s EHR systems, so much so that some states, such as Texas, have adopted position statements on the maintenance of accurate medical records.

In April 2015, Wynne M. Snoots, MD, released a position statement on behalf of the Texas Medical Board (TMB). It reads in part as follows:49

While the Electronic Medical Record (EMR) was intended to improve patient care, to date EMRs have primarily functioned to administer, structure, and memorialize the individual encounters, which is only a portion of the care process. Since the adoption of EMRs nationwide, this deviation from the initial intended primary function of the EMR to the actual function of the EMR has impacted the patient care process and caused some fragmentation of that process. Specifically, EMRs generate a much larger mass of often repetitive data which obscures key clinical medical information that is relevant to patient care and continuity of care, thus camouflaging the patient centric and longitudinal data that is crucial for improving the overall health of populations and for evaluating and treating patient-level medical problems.

To fulfill the overall objective of improving patient care while using EMRs, the necessary data elements must be properly identified, recorded, verified, and tagged in order to facilitate: 1) identification of relevant information; 2) accessibility to the information; and 3) transfer of information to patients and practitioners.

Therefore, it is incumbent on healthcare practitioners to be proactive and insure that their EMRs improve patient care by verifying that EMR data/information:

• Reflects accurate and complete information relevant to patient care.

• Memorialize each patient’s care over time.

• Facilitate communication and coordination among all members of a patient’s healthcare team.

• Guide those providing future care.

• Is transferred and exchanged with patients.

• Satisfies all regulatory duties.

• Assists in tracking for patient recall in the event of new health threats or new treatment options.

EMR technology, implementation and utilization are rapidly evolving and have presented numerous challenges along the way. In recent years, TMB has observed progressive difficulty obtaining medical decision making information from current records, which interferes with the accomplishment of our mission. It is not the role of the TMB to endorse EMR software or regulate technology. However, it is clearly within the TMB’s scope and oversight duties to set forth standards and expectations for creating and maintaining a useful, meaningful and readable medical record. Accordingly, the Texas Medical Board is confident that current information technology can meet this challenge, if the right focus is applied by practitioners; thereby fulfilling the priorities for clinicians, patients, administrators and all others who use the medical record for their own purposes—while keeping patient care paramount.

Perhaps one of the best examples of one of concerns expressed by the TMB about EHRs is that, unlike paper-based medical records, the EHR is proving to be a difficult witness in a court of law.50 Providers and attorneys alike are finding the outputs and screenshots from the EHR look nothing like the actual computer screen or data entry fields the provider saw, clicked, or keyed at the time he or she saw a patient or made a clinical decision. This dilemma is causing many problems for providers and attorneys alike because it is difficult for attorneys to take a deposition of a provider using the outputs from an EHR. In the paper era, the record was the paper record and the record reflected what the provider wrote and thought at the time the provider recorded or dictated his or her note. In the digital era, the providers and attorneys are finding that because EHR screenshots and the outputs look nothing like the tool the provider used to record his or her entries on a patient, it is very difficult for a provider to verify the authenticity of the information contained in the medical record. As a result, attorneys and a new team of expert witnesses now are tasked with spending hours reading, tracing, and reviewing the meta-data audit trails.51 Those jobs didn’t exist in the paper-based medical record era. Rather than being efficient tools, EHRs are now actually adding time and cost to the discovery process because there is no easy way to conduct testimony from providers or to search, cull, process, and produce relevant data from EHR systems today.51

To add further confusion about the medical record as evidence in a court of law, the introduction of new technologies, such as PHRs, mHealth devices,52 health social media, telemedicine, e-prescribing, interoperability, and the electronic exchange of health information all add a new dimension to the legal process of discovery, especially e-discovery. These new technologies may contain important and/or clinically relevant information about a patient, but the information may be inaccessible to the provider as it may reside in locations outside the patient’s EHR, or in a system or device outside the provider’s or organization’s control.

In some cases, a provider may have referenced or relied upon this information to make a treatment decision for a patient, and will have copies of the patient’s medical records obtained from other sources incorporated into the EHR system for reference. All relevant or potentially relevant information is discoverable. However, this information, along with other potentially relevant information, such as the patient’s genetic or genomic information, which presently resides outside of the EHR53 but is not considered to be part of the “legal medical record” or part of the individual’s HIPAA-designated record set, is released upon request for disclosure purposes.

Yet, under 45 CFR 164.524 an individual is entitled to their genetic or genomic information if they request it, along with “any item, collection, or grouping of information that includes PHI and is maintained, collected, used, or disseminated by or for a covered entity.”54

Under 45 CFR 164.524, organizations may be left unaware of the existence of an impending lawsuit in today’s digital era. A savvy attorney or plaintiff interested in going on a fishing expedition can request “complete copies” of “any and all of their PHI, in any form, or location wherever it may exist” (including all electronic PHI) and the organization under this rule would be required to provide the individual potential to their information.

It is generally easier for plaintiffs to identify and obtain anything potentially relevant they may need to initiate a malpractice claim than it is for a defendant to obtain all of the relevant clinical information that they may need to defend themselves. This is because at this time, there are no standards for the preservation of PHI from PHRs and other third-party medical devices, nor are PHRs, social health media, or other third-party medical devices defined as “legal medical records.” And sometimes, crucial clinically relevant information that may help a provider or an organization defend themselves against a malpractice claims may exist in a PHR, mHealth device, social media platform, or other medical device.

This presents a perplexing dilemma for the healthcare defense attorney because when it comes to the legal process of discovery, especially e-discovery, the process can be time consuming, expensive, and technically overwhelming. Yet, the need to obtain all relevant information is crucial to the defense of a lawsuit. The process will be even more challenging if the provider, organization, or legal counsel has not established a litigation response team that can respond to e-discovery requests, testify about the organization’s EHR systems, and address other information and record keeping systems within the organization. Paper-based record outputs no longer tell the complete story—rather, a team of technical experts is now needed to obtain the complete set of digital and paper records to reconstruct the events of a case. This is further complicated by the fact that there are no standards for easily searching, culling, processing and producing relevant clinical information from today’s EHR systems, not only for litigation, but for any clinical encounter. EHR systems, to be of any value in improving population health while reducing care delivery and litigation costs, will have to evolve to become more efficient and useful tools that are easily searchable and able to produce just the right clinical information at the right time. At the conclusion of the patient’s encounter, the clinical data in the EHR should accurately tell the patient’s story while justifying the diagnoses, treatment, length of stay, documentation, coding, and billing without providers, attorneys, and technical experts having to spend hours reconciling paper outputs, screen shots, HIPAA audit logs, metadata and data sets, and staffing logs in order to figure out what happened to a patient and why.

Until such time that standards are developed for the preservation of PHI from PHRs, health social media, and other third-party medical devices, or unless providers and organization are able to obtain copies of relevant clinical data from a patient’s PHR, health social media, or other medical devices through discovery, they will often be at a disadvantage because they are left unaware of the existence of crucial clinical data that they may need to defend themselves in a malpractice case.

Because there are no legal standards or systematic approaches for the submission of the EHR as evidence into a court of law, there continue to be privacy and security gaps, along with varying approaches in how health information is collected, stored, and used by entities not covered under HIPAA. The federal e-discovery rules that were enacted in 2006 and amended in 2010 and 2015 (and have been modeled in some state court systems) are the closest thing the industry has today as a standard approach for the discovery of information of EHR systems.

As we will examine later in this chapter, the federal e-discovery and evidence rules have begun to converge and overlap with the HIPAA 2016 OCR access rules. Covered entities, vendors, and legal professionals alike are now being mandated to take a close look at their organizations’ release-of-information processes and how their medical records are accessed and used as evidence in a court of law and for regulatory investigations.

As these processes conduct reviews of their systems, it is hoped that through the changes they are now undertaking, they will ultimately lead to the development of new standards, systems, and processes related to the definition of an organization’s HIPAA designated record set for disclosure purposes, and that the policies and procedures the organization will undergo when responding to various requests for patient information from patients and attorneys will be improved. It is also hoped that EHRs will evolve to become not only more interoperable but also searchable and able to produce the right summary of data at the right time based on the user’s query.

The USA PATRIOT Act, signed into law in October, 2001, by President George W. Bush, also significantly expanded the search and surveillance powers of the federal government and provides federal officials with greater access to medical records. This law impacts HIPAA privacy and security rules, and how a medical record can be used as evidence in a legal procedure.

Furthermore, the passage of the 2016 Cures Act has laid the foundation for a new era in the nation’s health information infrastructure through healthcare IT standards development to advance interoperability, assignment of penalties for blocking the sharing of electronic health records, development of registries through the exchange of EHR data and review, and development of HIPAA privacy and security rules governing human subjects protection (Common Rule) and the confidentiality of EHRs of individuals with behavioral health and substance use disorders.

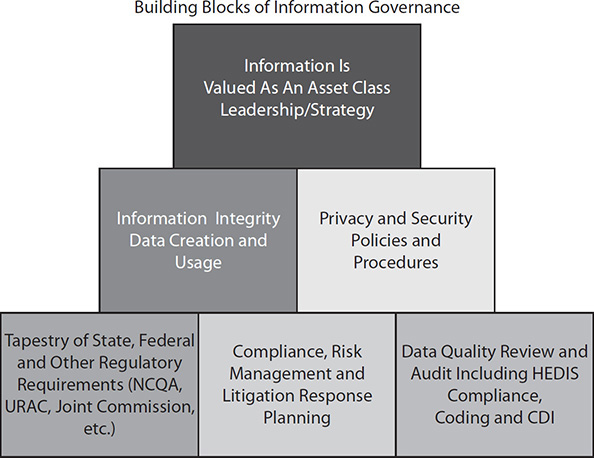

The efforts CMS is establishing to innovate and strengthen Medicare coupled with demands by consumers, providers, and payers that they be given access to their health information that exists in a wide variety of forms, formats, and locations (even outside the EHR) are causing many entities and providers to rethink the processes by which they manage health information, giving rise to a new era known as health information governance.55

This paradigm shift from the centralized management and processing of the release of health information requests to a more decentralized process in which the individual’s medical record can be more quickly and easily searched for the relevant information in a variety of forms, formats, and locations is necessary in order to meet the OCR’s goal of providing individuals with timely and robust access to their health data so they can be empowered and engaged in the care coordination and decision-making process.

Furthermore, as national security, surveillance, and the rooting out of terrorism become increasingly important to the federal government, the government is placing new demands upon healthcare organizations. These demands are to develop new health information and records management policies that include the ability to quickly and easily search the records of individuals suspected of involvement in federal crimes or terrorist activities, and establish policies that notify individuals of their privacy and security rights under both HIPAA and the USA PATRIOT Act.

Under HIPAA, medical records can be used as evidence for law enforcement purposes. Law enforcement officials can obtain an individual’s medical record without a warrant under the following circumstances:56

• To identify or locate a suspect, fugitive, witness, or missing person

• Instances where a crime has been committed on the premises of the covered entity

• In a medical emergency in connection with a crime

Under Section 215 of the USA PATRIOT Act,57 the FBI Director and/or his/her designee has the power to obtain a court order under the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA), “requiring the production of any tangible things (including books, records, papers, documents, and other items) for an investigation to protect against international terrorism or clandestine intelligence activities, provided that such investigation of a United States person is not conducted solely upon the basis of activities protected by the first amendment to the Constitution.” Like the provision under HIPAA that allows a law enforcement official to obtain copies of an individual’s medical records without a warrant, the FBI has the power to obtain medical records of individuals suspected of engaging in terrorism or clandestine intelligence activities.

EHR Standards for Records Management and Evidentiary Support

Electronic health records are a complex and evolving ecosystem. As such, the Health Level Seven (HL7) standards development organization (SDO) has developed an EHR system standard known as the Records Management and Evidentiary Support Functional Profile (RM-ES FP). This profile serves as a framework for the functions and conformance criteria for EHR systems to follow in the design and implementation of an EHR system. On a regular and ongoing basis, an HL7 volunteer workgroup meets to review and discuss EHR conformance criteria for the RM-ES profile. The HL7 RM-ES workgroup charter is as follows:58

The charge of the RM-ES project team is to provide expertise to the EHR work group, other standards groups and the healthcare industry on records management, compliance, and data/record integrity for EHR systems and related to EHR governance to support the use of medical records for clinical care and decision-making, business, legal and disclosure purposes.

The RM-ES Functional Profile is based on the premise that an “EHR-S must be able to create, receive, maintain, use, and manage the disposition of records for evidentiary purposes related to business activities and transactions for an organization. … This profile establishes a framework of system functions and conformance criteria as a mechanism to support an organization in maintaining a legally-sound health record.”59 Given this purpose, it is recommended that vendors and organizations alike regularly review this profile to receive guidance and updates for these purposes. The progress of the workgroup can be followed on the HL7 wiki.60

The Role and Use of the Medical Record in Litigation and/or Regulatory Investigations

As previously discussed, one of the important secondary uses of the medical record is to provide support and documentation for legal matters regardless of its form, format (paper, electronic as an EHR, EMR, PHR, mHealth device, etc.), or location, or who the custodian of the record is. The patient’s medical record also serves as an important form of evidence that is often used in the litigation process or as evidence in regulatory investigations. Yet the process by which medical records are discovered and admitted into evidence continues to change, evolve, and grow as rapidly as our nation’s health information infrastructure. Vast and significant differences exist between the role and use of paper versus EHRs as evidence in a court of law and whether or not the official custodian of the medical record is the provider who treated the patient or the individual who maintained the information on their PHR or mHealth device. The remainder of this chapter will focus on the legal process of discovery and the role of the medical record as evidence in a court of law.

Paper-based Medical Records vs. Electronic Health Records in Discovery

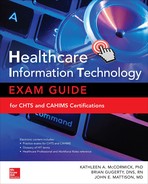

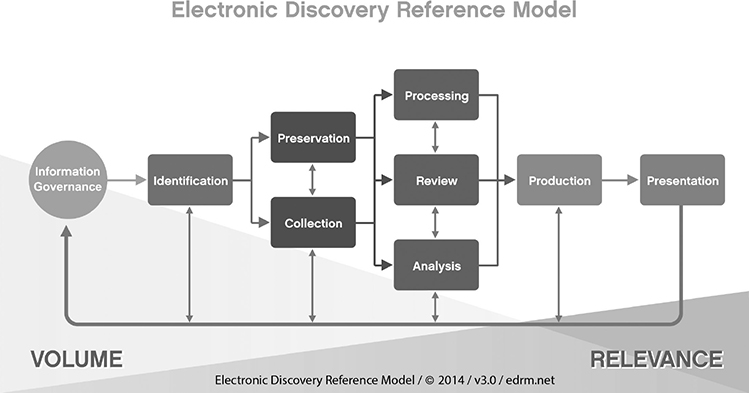

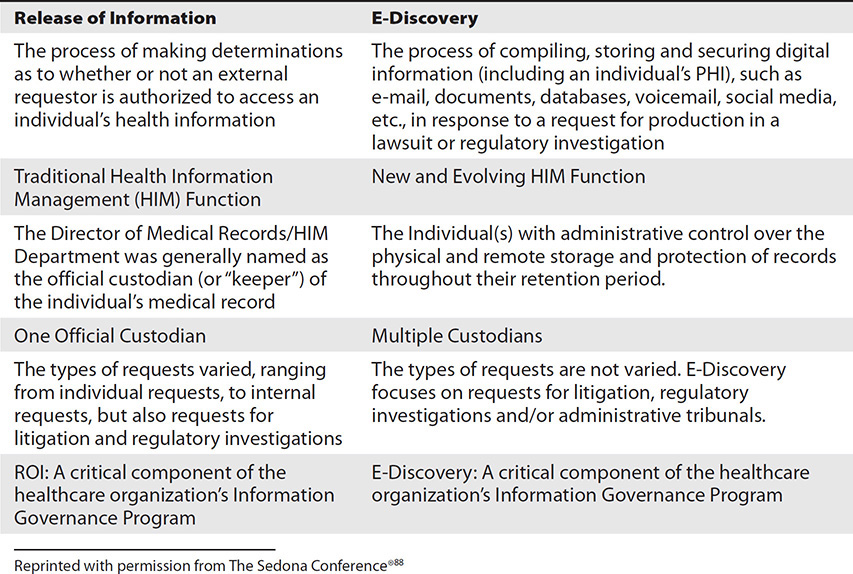

There are vast and important differences between paper-based medical records and electronic health records and the process by which the information is collected, preserved, processed, and produced for litigation and/or regulatory investigations. Table 17-1 provides a synopsis of these important differences. It is important to review and understand these differences because they describe how and why the legal process and standards surrounding the discovery of electronically stored information (ESI) from EHRs in litigation and regulatory investigations is in a state of constant growth and evolution.

Table 17-1 Synopsis of Differences Between Paper-Based Medical Records and EHRs

Although the federal mandate to implement EHRs was to improve healthcare quality and patient safety while reducing cost by an estimated $78 billion, the reality is that there are unintended consequences that also go along with the implementation of EHRs.61 These unintended consequences include but are not limited to design flaws and data entry and documentation errors, all of which can result in harm, or even death, to a patient.62 In Illinois, for example, a Chicago law firm won a record-breaking $8.25 million wrongful death settlement on behalf of a Chicago couple who suffered the loss of their infant son at only 40 days after a pharmacy technician typed the wrong information into a field in the hospital’s EHR system and the infant died from an excessive sodium overdose.63 To this day, this case serves as a call for action for some sort of regulatory oversight of the safety of EHR systems.

Litigation and regulatory investigations are a fact of life. With the advent of EHRs, EMRs, PHRs, and mHealth devices, the discovery process has become more complex and time consuming than ever before. It is very different from paper-based discovery. With EHRs and digital devices, a whole new team of professionals with very specific skills and background is needed to conduct forensic examinations of the digital data so testimony can be taken before the court as to what happened in a case and why. According to healthcare defense attorney and e-discovery expert Chad Brouillard, “healthcare institutions will be footing the bill for increasing demands by litigants who want access to the data, metadata, and the original displays of data as originally viewed by the clinicians. Those demands come with significant technical, administrative, and legal expenses, which are born solely by the parties in healthcare.”51

Discovery and Admissibility of the EHR

Whether a record that is requested for litigation is actually discoverable or will be admitted as evidence during the course of a trial may significantly affect the outcome of a lawsuit. Therefore, it is important to distinguish between the discoverability versus the admissibility of a record as evidence into a court of law. Following is a summary of the differences between discovery and admissibility:

• Discovery Discovery is defined as “the entire efforts of a party to a lawsuit and his/her/its attorneys to obtain information before trial through demands for production of documents, depositions of parties and potential witnesses, written interrogatories (questions and answers written under oath), written requests for admissions of fact, examination of the scene and the petitions and motions employed to enforce discovery rights. The theory of broad rights of discovery is that all parties will go to trial with as much knowledge as possible and that neither party should be able to keep secrets from the other (except for constitutional protection against self-incrimination).”64 Often much of the fight between the two sides in a suit takes place during the discovery period.

• Admissibility Admissibility denotes “evidence which the trial judge finds is useful in helping the trier of fact (a jury if there is a jury, otherwise the judge), and which cannot be objected to on the basis that it is irrelevant, immaterial, or violates the rules against hearsay and other objections. Sometimes the evidence an attorney tries to introduce has little relevant value (usually called probative value) in determining some fact, but prejudice from the jury’s shock at gory details may outweigh that probative value. In criminal cases the courts tend to be more restrictive on letting the jury hear such details for fear they will result in ‘undue prejudice.’ Thus, the jury may only hear a sanitized version of the facts in prosecutions involving violence.”65

The Federal Rules of Evidence (FRE)66

The Federal Rules of Evidence (FRE) are civil code adopted under the Rules Enabling Act that governs civil and criminal proceedings in federal court. The FRE are designed to secure judicial fairness, eliminate unjustifiable expense and delay, and promote the growth and development of the law of evidence. They provide for the exclusion of hearsay and exceptions to that rule. They also provide rules related to the authentication of evidence. For example, FRE Article X (Contents of Writings, Recordings and Photographs), Rule 101(1) sets forth the rules for the admission of digital writings, recordings, and photographs into a court of law. Under FRE Article X, writings and recordings are defined to include magnetic, mechanical, or electronic recordings. This means digital photographs that are stored on a computer are considered to be an original, and any exact copy of the digital photograph is admissible as evidence. (You should check your state’s rules of evidence for admissibility of digital recordings and photographs. Most states have enacted their own rules related to the admissibility of digital evidence into a court of law.)

The FRE have the force of statute, and the courts interpret them as they would any other statute. The Supreme Court promulgates the FRE, and they are amended from time to time by Congress, as they were in 2008, when FRE 502 was enacted to provide limitations on the waiver of attorney-client privilege and work product protection.

In September 2016, proposed amendments to FRE 803(16), Exceptions to the Rule Against Hearsay – Regardless of Whether the Declarant Is Available as a Witness – Statements in Ancient Documents, and FRE 902, Evidence That Is Self-Authenticating, were approved by the Judicial Conference Committee and submitted to the Supreme Court.67, 68 Barring any unforeseen changes, the amendments are expected to go into effect on December 1, 2017.

Medical Records as Hearsay

Hearsay is defined as “second-hand evidence in which the witness is not telling what he/she knows personally, but what others have said to him/her.”69 Under traditional rules of evidence, medical records are considered to be hearsay by a court of law. Hearsay is generally not admissible as evidence into a court of law, because the person who made the original statement is not available to be cross-examined. EHR systems and the electronic exchange of health information sometimes add more challenges to the hearsay rule because of the distinction between electronically stored information that was generated by the computer versus information that was entered by a user into a computer system. That said, “The courts have acknowledged the distinction between computer-generated and computer-stored information. ‘If the system made the statement it is “computer-generated.” If a person inputs a statement into the system that then preserves a record of it, it is “computer stored” evidence.’”70

Exceptions to the Hearsay Rule

Medical records are considered to be hearsay in the eyes of the court. However, they generally are admitted as evidence on other grounds. The most common way in which medical records are admitted as evidence into a court of law is through FRE 803. This rule is titled “Exceptions to the Rule Against Hearsay” and is also sometimes called the “business records exception.” It applies regardless of whether the declarant is available as a witness. Under FRE 803, there are 24 key exceptions to the rule against hearsay, regardless of whether the declarant is available as a witness:71 Summarized below are the most common exceptions to the hearsay rule that are used to admit medical records as evidence into a court of law.

• Present sense impression A statement describing or explaining an event or condition, made while or immediately after the declarant perceived it.

• Excited utterance A statement relating to a startling event or condition, made while the declarant was under the stress of the excitement that it caused.

• Then-existing mental, emotional, or physical condition A statement of the declarant’s then-existing state of mind (such as motive, intent, or plan) or emotional, sensory, or physical condition (such as mental feeling, pain, or bodily health), but not including a statement of memory or belief to prove the fact remembered or believed unless it relates to the validity or terms of the declarant’s will.

• Statement made for medical diagnosis or treatment A statement that is made for—and is reasonably pertinent to—medical diagnosis or treatment and describes medical history, past or present symptoms or sensations, their inception, or their general cause.

• Recorded recollection A record that is on a matter the witness once knew about but now cannot recall well enough to testify fully and accurately, was made or adopted by the witness when the matter was fresh in the witness’s memory, and accurately reflects the witness’s knowledge. If admitted, the record may be read into evidence but may be received as an exhibit only if offered by an adverse party.

• Records of a regularly conducted activity A record of an act, event, condition, opinion, or diagnosis that is admissible when it meets all of the following conditions:

• The record was made at or near the time by—or from information transmitted by—someone with knowledge.

• The record was kept in the course of a regularly conducted activity of a business, organization, occupation, or calling, whether or not for profit.

• Making the record was a regular practice of that activity.

• All these conditions are shown by the testimony of the custodian or another qualified witness, or by a certification that complies with Rule 902 or with a statute permitting certification.

• The opponent does not show that the source of information or the method or circumstances of preparation indicate a lack of trustworthiness.

• Absence of a record of a regularly conducted activity Evidence that a matter is not included in a record if the evidence is admitted to prove that the matter did not occur or exist when the record was regularly kept for a matter of that kind; and the opponent does not show that the possible source of the information indicates a lack of trustworthiness. The FRE and some states contain provisions that also make medical records admissible under the hearsay exception for public or official records, along with various other types of records such as marriage, birth, and death certificates and records from religious organizations.

You should check to determine if hearsay exception rules exist within your state. If so, understand what those exceptions are with regard to medical records and what the process is to authenticate and admit a medical record as evidence within your state. Medical records are also admissible in most states under workers’ compensation laws.

Physician-Patient Privilege

In certain circumstances, patients or healthcare providers may wish to safeguard protected health information from discovery by asserting a physician-patient relationship, thus shielding the protected health information from discovery. Nearly all states maintain statutes that protect the communications of a physician-patient relationship from disclosure in judicial or quasi-judicial proceedings under certain circumstances. The purpose of the physician-patient privilege doctrine is to encourage the patient to discuss and disclose all information for care and treatment.72

Incident Report Privilege

An incident report is a useful tool for making decisions regarding liability issues that may stem from the event for which the report was generated. As a general rule, incident reports are protected from discovery. However, in 2014, supreme court decisions in three states—Kentucky, Utah, and North Carolina—addressed the discoverability of incident reports and focused on three distinct aspects of the issues.

In Tibbs v. Bunnell73 the Kentucky Supreme Court held that data collected, maintained, and utilized as part of the Commonwealth of Kentucky’s Patient Safety Evaluation System (PSES) was not privileged under the Patient Safety Quality Improvement Act (PSQIA) and may be discovered.