CHAPTER 13

Navigating Health Data Standards and Interoperability

Joyce Sensmeier*

In this chapter, you will learn how to

• Discuss the need for health data standards

• Describe the standards development process and the organizations involved in it

• Delineate the importance of interoperability

• Describe current health data standards initiatives

• Explore the value of health data standards

Standards are foundational to the development, implementation, and interoperability of electronic health records (EHRs) and other health information technology (IT) systems. The effectiveness of healthcare delivery is dependent on the ability of clinicians to access health data and information when and where it is needed. The ability to exchange health information across organizational and system boundaries, whether between multiple departments within a single institution or among consumers, providers, payers, and other stakeholders, is essential. A harmonized set of rules and definitions, both at the level of data meaning and at the technical level of data exchange, is necessary to make this possible. There must also be a socio-political structure in place that recognizes the benefits of shared information and incentivizes the adoption and implementation of such standards.1

This chapter examines health data standards and interoperability in terms of the following topic areas:

• Need for health data standards

• Standards development process, organizations, and categories

• Knowledge representation

• Health data standards initiatives

• Business value of health data standards

Introduction to Health Data Standards

The ability to communicate in a way that ensures the message is received and the content is understood is dependent on the use of standards. Data standards are intended to reduce ambiguity in communication so that actions taken based on the data are consistent with the actual meaning of that data. In 2015, the Office of the National Coordinator for Health IT (ONC) published an interoperability vision for the future.2 In this future state all individuals, their families, and healthcare providers should be able to send, receive, find, and use electronic health information in a manner that is appropriate, secure, timely, and reliable to support the health and wellness of individuals through informed, shared decision-making. This vision requires the ability to capture, share, and analyze data to enable improvement in the health of individuals and populations.

While current information technologies are able to move and manipulate large amounts of data, they are not as proficient in dealing with ambiguity in the structure and semantic content of that data. The term “health data standards” is generally used to describe those standards related to the structure and content of health information. At this point, it may be useful to differentiate data from information and knowledge. Data are the fundamental building blocks on which health and healthcare decisions are based. Data can be unstructured such as free-form text, or structured in the form of discrete, standardized elements such as vital signs. When data are interpreted within a given context, as well as meaningful structure within that context, they become information. When information from various contexts is aggregated following a defined set of rules, it becomes knowledge and provides the basis for informed action.1 Data standards represent both data and their transformation into information. Data analysis generates knowledge, which is the foundation of professional practice standards.

Standards are created by several methods:3

• A group of interested parties comes together and agrees upon a standard.

• The government sanctions a process for standards to be developed.

• Marketplace competition and technology adoption introduces a de facto standard.

• A formal consensus process is used by a standards development organization (SDO) to publish standards.

The standards development process typically begins with a use case or business need that describes a system’s behavior as it responds to an external request. Technical experts then consider what methods, protocols, terminologies, or specifications are needed to address the requirements of the use case. An open and transparent consensus or balloting process is desirable to ensure that the developed standards have representative stakeholder input, which minimizes bias and encourages marketplace adoption and implementation.

Legislated, government-developed standards are able to gain widespread acceptance by virtue of their being required either by regulation or in order to participate in large, government-funded programs, such as Medicare. The healthcare IT industry is motivated to adopt and implement these standards into proprietary information systems and related products in order to be in compliance with these regulations and achieve a strong market presence. Because government-developed standards are in the public domain, usually they are made available at little or no cost and can be incorporated into any information system; however, they are often developed to support particular government initiatives and may not be as suitable for general, private-sector use. Also, given the amount of overhead attached to the legislative and regulatory process, it is likely that maintenance of these standards may lag behind fast-paced changes in technology and the general business environment.

Standards developed by SDOs are typically consensus-based and reflect the perspectives of a wide variety of interested stakeholders. They tend to be robust and adaptable across a wide range of implementations; however, most SDOs are nonprofit organizations that rely on the commitment of dedicated volunteers to develop and maintain standards. This often limits the amount of work that can be undertaken in a certain time frame. In addition, the consensus process can be time consuming and may result in a slow development process that does not always keep pace with technologic change. Perhaps the most problematic aspect of consensus-based standards is that there is no mechanism to ensure that they are adopted by the industry, because there is usually little infrastructure in place to actively and aggressively market them. This has resulted in the development of many technically competent standards that are never implemented.

In spite of our best efforts, standards development is not always a smooth or simple process. “Conflict may occur in the development of the standards, for example, within the confines of a technical committee designing a particular standard, where participants may disagree over the nature of the standard to be developed, or where one or more participants may take part in order to block the creation of a new standard, or by virtue of competition among supporters of several incompatible extant standards.”4 The American National Standards Institute (ANSI) is the private, nonprofit organization that administers and coordinates the U.S. voluntary standards and conformity assessment system. In this role, ANSI oversees the development and use of voluntary consensus standards by accrediting the procedures used by SDOs and approving their finished documents as American National Standards.

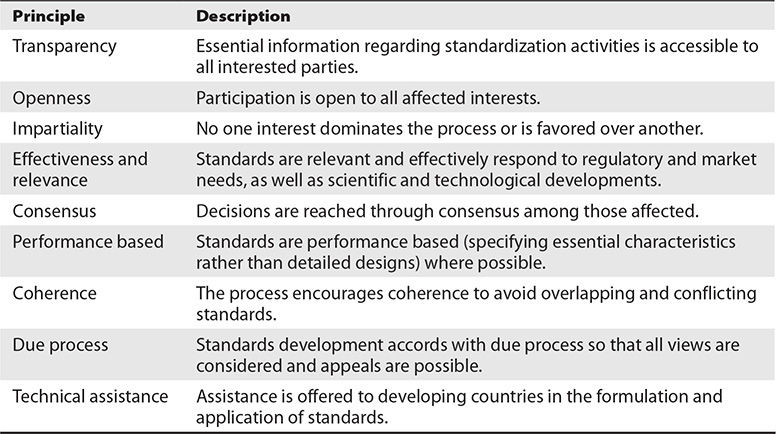

The United States Standards Strategy5 emphasizes that standards development should be open and inclusive, market driven, sector based, consumer focused, and globally relevant. The U.S. standardization system is based on the set of globally accepted principles for standards development shown in Table 12-1.

Table 13-1 ANSI Principles for Standards Development

Standards Categories

Several general topic areas are used to categorize health data standards. However, as interoperability efforts advance, their boundaries increasingly overlap.6 Health data interchange and transport standards are used to establish a common, predictable, secure communication protocol between and among systems. Vocabulary and terminology standards consist of standardized nomenclatures and code sets used to describe clinical problems and procedures, medications, and allergies. Content and structure standards and value sets are used to share clinical information such as clinical summaries, prescriptions, and structured electronic documents. Security standards include those standards used for authentication, access control, and transmission of health data.

Health Data Interchange and Transport Standards

Health data interchange and transport standards primarily address the format of messages and documents that are exchanged between computer systems. To achieve data compatibility between systems, it is necessary to have prior agreement on the syntax of the messages to be exchanged. That is, the receiving system must be able to divide the incoming message into discrete data elements that reflect what the sending system wishes to communicate. This section describes some of the major organizations involved in the development of health data interchange and transport standards.

Accredited Standards Committee X12

Accredited Standards Committee (ASC) X12 has developed a broad range of electronic data interchange (EDI) standards to facilitate electronic business transactions. In the healthcare arena, X12N standards have been adopted as national standards for such administrative transactions as claims, enrollment, and eligibility in health plans, and first report of injury under the requirements of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) of 1996 Privacy and Security Rules.

Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers

The Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE) has developed a series of standards known collectively as P1073 Medical Information Bus, which support real-time, continuous, and comprehensive capture and communication of data from bedside medical devices such as those found in intensive care units, operating rooms, and emergency departments. These data include physiologic parameter measurements and device settings. IEEE standards for information technology focus on telecommunications and information exchange between systems including local area networks (LANs) and metropolitan area networks (MANs).

Current IEEE standards development activities include efforts to develop standards that support wireless technology. The IEEE 802.xx suite of wireless networking standards, supporting LANs and MANs, has advanced developments in the communications market. The most widely known standard, 802.11 (commonly referred to as Wi-Fi), allows anyone with a “smart” mobile device or computer with either a plug-in card or built-in circuitry to connect wirelessly to the Internet.

National Electrical Manufacturers Association

The National Electrical Manufacturers Association (NEMA), in collaboration with the American College of Radiology (ACR) and others, formed Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine (DICOM) to develop a generic digital format and a transfer protocol for biomedical images and image-related information. DICOM enables the transfer of medical images in a multivendor environment and facilitates the development and expansion of picture archiving and communication systems (PACSs).

World Wide Web Consortium

The World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) is the main international standards organization for development of standards for the Web. W3C also publishes Extensible Markup Language (XML), which is a set of rules for encoding documents in machine-readable format. XML is most commonly used in exchanging data over the Internet. Although XML’s design focuses on documents, it is widely used for the representation of arbitrary data structures, for example in Web Services. Web Services use XML messages that follow the Simple Object Access Protocol (SOAP) standard and have been popular with the traditional enterprise. Other data exchange protocols include the Representational State Transfer (REST) architectural style, which focuses on a specific set of interactions between data elements rather than more complex implementation details. REST enables communication via the Hypertext Transfer Protocol (HTTP), which is used in web browsers. The largest known implementation of a system conforming to the REST architectural style is the Web.

Vocabulary and Terminology Standards

A fundamental requirement for effective communication is the ability to represent concepts unambiguously for both the sender and receiver of the message. While there have been great advances in the ability of computers to process natural language, most communication between health information systems relies on the use of structured vocabularies, terminologies, code sets, and classification systems to represent healthcare concepts. Standardized terminologies enable data collection at the point of care; enable retrieval of data, information, and knowledge in support of clinical practice; and elicit outcomes. The following examples describe several of the major vocabulary and terminology standards.

Current Procedural Terminology

The Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) code set maintained by the American Medical Association (AMA) describes medical, surgical, and diagnostic services. When medical, surgical, or diagnostic services are provided, they are translated into CPT codes and reported to third-party payers for reimbursement. Every medical insurance payer recognizes CPT codes as the standard by which medical procedures in ambulatory care are described in a universal language with specific meaning. While primarily used in the United States for reimbursement purposes, CPT codes have also been adopted for other data purposes.

International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems: Tenth Revision (ICD-10)

The International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems: Tenth Revision (ICD-10) is the most recent version of the ICD classification system for mortality and morbidity used worldwide. The ICD, maintained by the World Health Organization (WHO), is designed as a healthcare classification system, providing a system of diagnostic codes for classifying diseases and health conditions, as well as procedure codes for hospital-based services and procedures. The transition to ICD-10 in the United States occurred on October 1, 2015. Moving to the new ICD-10 code sets improves efficiencies and lowers administrative costs by replacing a dysfunctional, outdated classification system.

Nursing and Other Domain-specific Terminologies

The American Nurses Association continues to advocate for the use of the ANA-recognized terminologies supporting nursing practice within EHR and other health information technology solutions.7 Therefore, in alignment with national requirements for standardization of data and information exchange, ANA supports the following recommendations:

• “All health care settings should create a plan for implementing an ANA recognized terminology supporting nursing practice within their EHR.

• Each setting type should achieve consensus on a standard terminology that best suits their needs and select that terminology for their EHR, either individually or collectively as a group (e.g., EHR user group).

• Education should be available and guidance developed for selecting the recognized terminology that best suits the needs for a specific setting.

• When exchanging information (e.g., for problems and care plans) with another setting using Health Level Seven’s (HL7) Consolidated Clinical Document Architecture (C-CDA), Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine–Clinical Terms (SNOMED CT®) and Logical Observation Identifiers Names and Codes (LOINC®) should be used. LOINC® should be used for coding nursing assessments and outcomes and SNOMED CT® for problems, interventions, and observation findings.

• Health information exchange between providers using the same terminology does not require conversion of the data to SNOMED CT® or LOINC® codes.”

RxNorm

RxNorm is a standardized nomenclature for clinical drugs and drug delivery devices produced by the National Library of Medicine (NLM). The goal of RxNorm is to allow various systems using different drug nomenclatures to share data efficiently at the appropriate level of abstraction. RxNorm contains the names of the prescription formulations that exist in the United States, including devices that administer the medications in a pack containing multiple clinical drugs or clinical drugs designed to be administered in a specified sequence.

Unified Medical Language System

The Unified Medical Language System (UMLS) consists of a metathesaurus—a large, multipurpose, and multilingual thesaurus—that contains millions of biomedical and health-related concepts, their synonymous names, and their relationships managed by NLM. There are specialized vocabularies, code sets, and classification systems for almost every practice domain in healthcare. Most of these are not compatible with one another, and much work needs to be done to achieve usable mapping and linkages between them. NLM is the central coordinating entity for clinical terminology standards within the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). NLM works closely with the Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology to advance national goals toward achieving an interoperable health information technology infrastructure that improves the quality and efficiency of healthcare.8

Content and Structure Standards

Content and structure standards relate to the data content that is transported within information exchanges. Such standards define the structure and content organization of the electronic message/document information content. They can also define a set of content standards (messages/documents). In addition to standardizing the format of health data messages and the lexicons and value sets used in those messages, there is widespread interest in defining common sets of data for specific message types. A minimum or core data set is “a minimum set of items with uniform definitions and categories concerning a specific aspect or dimension of the healthcare system which meets the essential needs of multiple users.”9

Clinical Data Interchange Standards Consortium

The Clinical Data Interchange Standards Consortium (CDISC) is a global, multidisciplinary consortium that has established standards to support the acquisition, exchange, submission, and archiving of clinical research data and metadata. CDISC develops and supports global, platform-independent data standards that enable information system interoperability to improve medical research and related areas of healthcare. One example is the Biomedical Research Integrated Domain Group (BRIDG) model, a domain-analysis model representing protocol-driven biomedical/clinical research. The BRIDG model emerged from an unprecedented collaborative effort among clinical trial experts from CDISC, the National Institutes of Health (NIH)/National Cancer Institute (NCI), the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), Health Level Seven International (HL7), and other volunteers. This structured information model is being used to support development of data interchange standards and technology solutions that will enable harmonization between the biomedical/clinical research and healthcare arenas.10

Health Level Seven International

Health Level Seven International (HL7) is a standards organization that develops standards in multiple categories including health data interchange, content, and structure. HL7 standards cover a broad spectrum of areas for information exchange including medical orders, clinical observations, test results, admission/transfer/discharge, EHR data, and charge and billing information. One of the emerging standards developed by HL7 for exchanging health information electronically is Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources (FHIR). FHIR uses a predominantly composition approach (rather than modeling by constraint) and is organized using a combination of building blocks called resources. FHIR specifies a RESTful application programming interface (API) to access resources. Several projects are underway through standards organizations to facilitate adoption of FHIR including the Clinical Information Modeling Initiative (CIMI) and SMART on FHIR.11

International Health Terminology Standards Development Organisation

The International Health Terminology Standards Development Organisation (IHTSDO) is a not-for-profit association in Denmark that develops and promotes use of SNOMED CT (Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine—Clinical Terms) to support safe and effective health information exchange. It was formed in 2006 with the purpose of developing and maintaining international health terminology systems. SNOMED CT is a comprehensive clinical terminology, originally created by the College of American Pathologists (CAP) and, as of April 2007, owned, maintained, and distributed by IHTSDO. CAP continues to support SNOMED CT operations under contract to IHTSDO and provides SNOMED CT–related products and services as a licensee of the terminology. NLM is the U.S. member of IHTSDO and, as such, distributes SNOMED CT at no cost in accordance with the member rights and responsibilities outlined in IHTSDO’s Articles of Association.12

National Council for Prescription Drug Programs

The National Council for Prescription Drug Programs (NCPDP) develops both content and health data interchange standards for information processing in the pharmacy services sector of the healthcare industry. As an example of the impact that standardization can have, since the introduction of these standards in 1992, the retail pharmacy industry has moved to 100 percent electronic claims processing in real time. NCPDP standards are also forming the basis for electronic prescription transactions. Electronic prescription transactions are defined as EDI messages flowing between healthcare providers (i.e., pharmacy software systems and prescriber software systems) that are concerned with prescription orders. NCPDP’s Telecommunication Standard Version 5.1 was named the official standard for pharmacy claims within HIPAA, and NCPDP is also named in other U.S. federal legislation titled the Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement, and Modernization Act. Other NCPDP standards include the SCRIPT Standard for Electronic Prescribing and the Manufacturers Rebate Standard.13

Security Standards

Information security practices are increasingly important in a world of virtual access to health data and information. These practices require guidelines and general principles for initiating, implementing, maintaining, and improving information security management within and between organizations. Chapters 25–31 provide a detailed description of the healthcare security standards and effective security management practices in use today.

Standards Coordination and Interoperability

It has become clear to many public- and private-sector standards advocates that no one entity has the resources to create an exhaustive set of health data standards that will meet all needs. New emphasis is being placed on coordinating efforts and leveraging existing standards to eliminate the redundant and siloed efforts that have in the past contributed to a complex, difficult-to-navigate, health data standards environment. SDOs and other industry groups are actively working together to develop standards that achieve technical, structural, and semantic interoperability.14 As a result, the standards development and, more importantly, adoption process is more accelerated and streamlined, and the healthcare industry is moving closer to achieving the goal of sharable, comparable, quality data based on evidence.15

In addition to the various SDOs previously described, the following sections provide brief descriptions of some of the major international, national, and regional organizations involved in broad-based standards coordination and interoperability.

Health IT Standards Committee

The American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) provided for the creation of the Health IT Standards Committee (HITSC) under the auspices of the Federal Advisory Committee Act (FACA). The committee is charged with making recommendations to the ONC on standards, implementation specifications, and certification criteria for the electronic exchange and use of health information. In developing, harmonizing, or recognizing standards and implementation specifications, the committee also provides for the testing of the same by the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST). Recently, the committee has formed several taskforces comprising stakeholder representatives and subject matter experts focused on precision medicine, as well as the 2017 Interoperability Standards Advisory.16

International Organization for Standardization

The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) develops, harmonizes, and publishes standards internationally. ISO standards are developed, in large part, from standards brought forth by member countries, and through liaison activities with other SDOs. Often, these standards are further broadened to reflect the greater diversity of the international community. In 1998, the ISO Technical Committee (TC) 215 on Health Informatics was formed to coordinate the development of international health information standards, including data standards. Consensus on these standards influences health informatics standards adopted in the United States. At times, other SDOs collaborate with ISO TC 215 to accredit international standards. For example, both HL7 and ISO TC 215 accredited the EHR System Functional Model as a set of requirements specifying the behavior of EHR systems.

Integrating the Healthcare Enterprise

Standards, while a necessary part of the interoperability solution, are not alone sufficient to fulfill the needs. Simply using a standard does not necessarily guarantee that health information exchange will occur within and across organizations and systems. Standards can be implemented in multiple ways, so implementation specifications or guides are critical to make interoperability a reality. Standard implementation guides, or profiles, are designed to provide specific configuration instructions or constraints for implementation of a particular standard or set of standards to achieve the desired interoperable result based on a domain-specific use-case scenario.

Integrating the Healthcare Enterprise (IHE) is an international organization that provides a detailed framework for implementing standards, filling the gaps between creating the standards and implementing them. Through its open, consensus process, IHE has published a large body of detailed specifications or guides, called profiles, that are being implemented globally today by healthcare providers and regional health information exchanges to enable standards-based, safe, secure, and efficient health information exchange. IHE maintains the Product Registry, which is used as a mechanism for registering and searching products that support IHE profiles. Users can then reference the appropriate IHE profiles in requests for proposals, thus simplifying the systems acquisition process and furthering the adoption of standards-based, interoperable systems.17

eHealth Exchange and the Sequoia Project

The eHealth Exchange (commonly referred to as “the Exchange”) is a group of federal agencies and nonfederal entities organized under a common mission and purpose to improve patient care, streamline disability benefit claims, and improve public health reporting through secure, trusted, and interoperable health information exchange. By leveraging a common set of standards, legal agreement, and governance, eHealth Exchange participants are able to securely share health information with each other, without additional customization and one-off legal agreements. The eHealth Exchange connectivity spans across all 50 states and is now the largest health data sharing network in the United States.18

The Business Value of Health Data Standards

Clearly the importance of health data standards in enhancing the quality and efficiency of healthcare delivery is being recognized by national and international leadership. Reviewing the business value of defining and using data standards is critical for driving the implementation of these standards into applications and systems. Having health data standards for data exchange and information modeling will provide a mechanism against which deployed systems can be validated.19 Reducing manual intervention will increase worker productivity and streamline operations. Defining information exchange requirements will enhance the ability to automate interaction with external partners, which in turn will decrease costs.

By using data standards to develop their emergency-department data-collection system, New York State demonstrated that it is good business practice.20 Their project was completed on time without additional resources and generated a positive return on investment. The use of standards provided the basis for consensus between the hospital industry and the state, a robust pool of information that satisfied the users, and the structure necessary to create unambiguous data requirements and specifications.

Other economic stakeholders for healthcare IT include software vendors or suppliers, software implementers who install the software to support end-user requirements, and the users who must use the software to do their work. The balance of interests among these stakeholders is necessary to promote standardization to achieve economic and organizational benefits.21 Defining clear business measures will help motivate the advancement and adoption of interoperable healthcare IT systems, thus ensuring the desired outcomes can be achieved. Considering the value proposition for incorporating data standards into products, applications, and systems should be a part of every organization’s information technology strategy. The development, adoption, and use of standards-based interoperable healthcare IT will enable the achievement of better care, improved population health, and cost reduction.

Chapter Review

This chapter introduced health data standards; the organizations that develop, coordinate, and harmonize them; the process by which they are developed; examples of current standards initiatives; and a discussion of the business value of health data standards. Four broad areas were described to categorize health data standards. Health data interchange and transport standards are used to establish a common, predictable, secure communication protocol between and among systems. Vocabulary and terminology standards consist of standardized nomenclatures and code sets used to describe clinical problems and procedures, medications, and allergies. Content and structure standards and value sets are used to share clinical information such as clinical summaries, prescriptions, and structured electronic documents. Finally, security standards are used for authentication, access control, and transmission of health data. Organizations involved in the development, harmonization, coordination, and implementation of health data standards were described.

A discussion of the standards development process highlighted the international and socio-political context in which standards are developed and the potential impact they have on the availability and currency of standards. The expanding role of the federal government in influencing the development and adoption of health data standards was discussed. Finally, the chapter emphasized the business value and importance of health data standards and their adoption in improving the quality and efficiency of healthcare delivery and health outcomes.

Questions

To test your comprehension of the chapter, answer the following questions and then check your answers against the list of correct answers that follows the questions.

1. Why is the healthcare IT industry motivated to adopt and implement legislated, government-developed standards into proprietary information systems and related products?

A. Government-developed standards are more suitable for general, private-sector use.

B. Maintenance of government-developed standards is typically on a fast pace.

C. Government-developed standards typically enable compliance with regulations.

D. Bureaucratic overhead is lessened with government-developed standards.

2. Which of the following principles is not included in the globally accepted principles for standards development set forth in ANSI’s United States Standards Strategy?

A. Transparency

B. Openness

C. Consensus

D. Complexity

3. What are the broad areas used to categorize health data standards?

A. Health data interchange and transport, vocabulary and terminology, content and structure, security

B. Health data exchange, structured, content, security

C. Terminology, vocabulary, content, privacy

D. Nomenclatures, code sets, protocols, and transactions

4. Which of the following organizations is involved in the development of health data interchange standards?

A. American Medical Association (AMA)

B. Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE)

C. American Nurses Association (ANA)

D. National Library of Medicine (NLM)

5. Interoperability can be more rapidly advanced through coordinated, joint standards-development efforts. Which of the following is a recent example of such a joint effort between CDISC and NIH/NCI, the FDA, and HL7?

A. EHR System Functional Model

B. Precision Medicine Initiative

C. Consolidated CDA

D. BRIDG model

6. Integrating the Healthcare Enterprise (IHE) has developed a mechanism for registering and searching products that support IHE profiles. What is this mechanism called?

A. IHE Technical Framework

B. Consolidated CDA guide

C. IHE Product Registry

D. IHE Integration Statements

7. Which of the following does not represent a business value of health data standards?

A. Reduced costs

B. Decreased worker productivity

C. Reduced manual intervention

D. Ability to validate deployed systems

8. When New York State used data standards to develop their emergency-department data-collection system, which of the following outcomes resulted?

A. Need for additional resources

B. Dissatisfied users

C. Ambiguous data requirements

D. Positive return on investment

Answers

1. C. The healthcare IT industry is motivated to adopt and implement government-developed standards into proprietary information systems and related products in order to be in compliance with these regulations and achieve a strong market presence.

2. D. Complexity is not included in the set of globally accepted principles for standards development. The nine principles are transparency, openness, impartiality, effectiveness and relevance, consensus, performance based, coherence, due process, and technical assistance.

3. A. The four broad areas used to categorize health data standards are health data interchange standards (used to establish a common, predictable, secure communication protocol between and among systems); vocabulary standards (standardized nomenclatures and code sets); content standards (used to share clinical information); and security standards (used for authentication, access control, and transmission of health data).

4. B. The Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE) has developed a series of standards that focus on telecommunications and information exchange between systems, including local and metropolitan area networks.

5. D. In a recent, joint standards-development effort, the Clinical Data Interchange Standards Consortium (CDISC) published the BRIDG model. This model was produced and developed through the joint efforts of the National Institutes of Health (NIH)/National Cancer Institute (NCI), the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and Health Level Seven International (HL7).

6. C. IHE maintains the Product Registry as a mechanism for registering and searching products that support IHE profiles. The registry includes IHE Integration Statements, which are documents prepared and published by vendors that describe the conformance of their products with the IHE Technical Framework.

7. B. Having health data standards for data exchange and information modeling will provide a mechanism against which deployed systems can be validated. Reducing manual intervention will increase (not decrease) worker productivity and streamline operations. Defining information exchange requirements will enhance the ability to automate interaction with external partners, which will reduce costs.

8. D. By using data standards to develop their emergency-department data-collection system, New York State completed their project on time without additional resources and generated a positive return on investment. The use of standards provided the basis for consensus between the hospital industry and the state, a robust pool of information that satisfied the users, and the structure necessary to create unambiguous data requirements and specifications.

References

1. Saba, V. K., & McCormick, K. A. (Eds.). (2015). Essentials of nursing informatics, Sixth edition. McGraw-Hill Education.

2. Office of the National Coordinator for Health IT. (2015). Connecting health and care for the nation: A shared nationwide interoperability roadmap. Accessed from www.healthit.gov/sites/default/files/hie-interoperability/nationwide-interoperability-roadmap-final-version-1.0.pdf.

3. Hammond, W. E. (2005). The making and adoption of health data standards. Health Affairs, 24(5), 1205–1213.

4. Busch, L. (2011). Standards: Recipes for reality. MIT Press.

5. ANSI. (2015). United States Standards Strategy. American National Standards Institute. Accessed from www.us-standards-strategy.org.

6. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). (2015). 2015 edition health information technology (health IT) certification criteria, 2015 edition base electronic health record (EHR) definition, and ONC health IT certification program modifications; final rule. 45 CFR 170. Federal Register, 80(60), 16804–16921. Accessed from www.federalregister.gov/documents/2015/10/16/2015-25597/2015-edition-health-information-technology-health-it-certification-criteria-2015-edition-base.

7. American Nurses Association. (2015). Inclusion of recognized terminologies within EHRs and other health information technology solutions. Accessed from www.nursingworld.org/MainMenuCategories/Policy-Advocacy/Positions-and-Resolutions/ANAPositionStatements/Position-Statements-Alphabetically/Inclusion-of-Recognized-Terminologies-within-EHRs.html.

8. U.S. National Library of Medicine. (2016). Health information technology and health data standards at NLM. Accessed from www.nlm.nih.gov/healthit/index.html.

9. HHS, Health Information Policy Council. (1983). Background paper: Uniform minimum health data sets (unpublished).

10. Clinical Data Interchange Standards Consortium (CDISC). www.cdisc.org/.

11. Wagholikar, K. B., Mandel, J. C., Klann, J. G., Watanasin, N., Mendis, M., Chute, C. G., Mandl, K. D., & Murphy, S. N. (2016). SMART-on-FHIR implemented over i2b2. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association. Accessed from http://jamia.oxfordjournals.org/content/early/2016/06/05/jamia.ocw079.

12. International Health Terminology Standards Development Organisation (IHTSDO). www.ihtsdo.org/.

13. National Council for Prescription Drug Programs (NCPDP). www.ncpdp.org/.

14. Harris, M. R., Langford, L. H., Miller, H., Hook, M., Dykes, P. C., & Matney, S. A. (2015). Harmonizing and extending standards from a domain-specific and bottom-up approach: An example from development through use in clinical applications. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, 22(3), 545–552.

15. McCormick, K. A., Sensmeier, J., Dykes, P. C., Grace, E. N., Matney, S. A., Schwarz, K. M., & Weston, M. J. (2015). Exemplars for advancing standardized terminology in nursing to achieve sharable, comparable quality data based upon evidence. Online Journal of Nursing Informatics (OJNI), 19(2). Available at www.himss.org/ojni.

16. Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology (ONC)/HEALTHIT. www.healthit.gov/isa/.

17. Windle, J. R., Katz, A. S., Dow, J. P., Fry, E. T. A., Keller, A. M., Lamp, T., … Weintraub, W. S. (2016, September). 2016 ACC/ASE/ASNC/HRS/SCAI health policy statement on integrating the healthcare enterprise. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 68(12), 1348–1364.

18. http://sequoiaproject.org/ehealth-exchange/about/.

19. Loshin, D. (2004). The business value of data standards. DM Review, 14, 20.

20. Davis, B. (2004). Return-on-investment for using data standards: A case study of New York State’s data system. Accessed from www.phdsc.org/standards/pdfs/ROI4UDS.pdf.

21. Marshall, G. F. (2009, October). The standards value chain: Where health IT standards come from. Journal of AHIMA, 80(10), 54–55, 60–62.

Additional Study

The field of health data standards is a very dynamic one, with existing standards undergoing revision and new standards being developed. The best way to learn about specific standards activities is to get involved in the process. All of the organizations discussed in this chapter provide opportunities to be involved with activities that support standards development, coordination, and implementation. The following list includes the web address for each organization. Most sites describe current available activities and publications, and many have links to other related sites.

Accredited Standards Committee (ASC) X12: www.x12.org

American Medical Association (AMA): www.ama-assn.org

American National Standards Institute (ANSI): www.ansi.org

American Nurses Association (ANA): www.nursingworld.org

Clinical Data Interchange Standards Consortium (CDISC): www.cdisc.org

Digital Imaging Communication in Medicine Standards Committee (DICOM): http://dicom.nema.org/

eHealth Exchange and the Sequoia Project: www.sequoiaproject.org

Health Level Seven International (HL7): www.hl7.org

Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE): www.ieee.org

Integrating the Healthcare Enterprise (IHE): www.ihe.net

IHE Product Registry: http://product-registry.ihe.net

International Health Terminology Standards Development Organisation (IHTSDO): www.ihtsdo.org

International Organization for Standardization (ISO): www.iso.org

International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD-10): www.cdc.gov/nchswww

National Committee on Vital and Health Statistics (NCVHS): www.ncvhs.hhs.gov

National Council for Prescription Drug Programs (NCPDP): www.ncpdp.org

National Electrical Manufacturers Association (NEMA): www.nema.org

National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST): www.nist.gov

National Library of Medicine (NLM): www.nlm.nih.gov/healthit.html

Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology (ONC): www.healthit.gov

Public Health Data Standards Consortium (PHDSC): www.phdsc.org

RxNorm: www.nlm.nih.gov/research/umls/rxnorm

Unified Medical Language System (UMLS): www.nlm.nih.gov/research/umls

World Health Organization International Classification of Diseases (WHO-ICD): www.who.int/classifications/icd/en

World Wide Web Consortium (W3C): www.w3.org

*Adapted from Virginia K. Saba and Kathleen A. McCormick, Essentials of Nursing Informatics, Sixth Edition, 101–113. © 2015 by McGraw-Hill Education.