CHAPTER 2

Futures Markets

Aims

- To examine trading arrangements for futures contracts, including delivery of the underlying asset, margin requirements and closing out.

- To interpret futures quotes, including the settlement price and open interest.

- To discuss the different types of futures traders.

We have already discussed the basic principles behind forward and futures contracts. Forward contracts are analytically easier to deal with than futures contracts and so we often apply mathematical results from forwards (e.g. pricing forward contracts) to futures contracts. However, there are differences in practice between the two types of contract and we discuss the mechanics of both of these contracts in this chapter.

2.1 TRADING ON FUTURES MARKETS

Forward contracts are traded over-the-counter (OTC) whereas most futures are traded on an exchange and the differences between these two approaches are summarised in Table 2.1.

TABLE 2.1 Derivatives markets

| Over-the-counter | Exchanges |

|

|

The range of assets on which futures contracts are written is very wide and they are traded on a large number of exchanges around the world (Table 2.2). The basic requirements in buying and selling different types of futures contracts and using them for hedging and speculation are very similar, even though futures contracts are written on a diverse set of underlying assets (e.g. gold, oil, wheat, stocks, stock indices, T-bills, T-bonds, interest rates). The growth in futures contracts is primarily due to the increased volatility of the price of the underlying assets and the need to hedge this risk. Futures contracts which trade in a highly liquid market (with low bid–ask spreads and low commissions) are available on a wide variety of underlying assets, whereas only the OTC forward market for foreign exchange rivals the volume of trading on futures markets.

TABLE 2.2 Financial futures

| Instruments | Exchanges |

|

|

A futures exchange is usually a corporate entity whose members elect a board of directors, who decide on the terms and conditions under which existing contracts are traded and whether to introduce new contracts (subject usually to the regulatory authority which in the US is the Commodity Futures Trading Commission [CFTC]).

Each futures contract specifies a delivery month. The quoted futures price varies continuously as the spot (cash market) price changes. Consider a futures contract where the underlying asset is the stock of AT&T. Today (15 May), a buyer of the September futures contract at a quoted price ![]() is said to be long the futures contract. If she holds the contract to maturity (25 September) then she must purchase the underlying asset in the futures contract (i.e. AT&T stock) in Chicago (the delivery point) at a price of

is said to be long the futures contract. If she holds the contract to maturity (25 September) then she must purchase the underlying asset in the futures contract (i.e. AT&T stock) in Chicago (the delivery point) at a price of ![]() on 15 September (maturity date), even if the spot price on the NYSE for AT&T stock is, say,

on 15 September (maturity date), even if the spot price on the NYSE for AT&T stock is, say, ![]() or

or ![]() . So, if you hold the futures contract to maturity you must take delivery of the underlying asset and pay the futures price

. So, if you hold the futures contract to maturity you must take delivery of the underlying asset and pay the futures price ![]() in Chicago – you have no choice in the matter.

in Chicago – you have no choice in the matter.

The writer or seller of the futures at a quoted price ![]() is said to be short the contract and if she holds the contract to maturity, she must deliver and sell AT&T stock for the price of

is said to be short the contract and if she holds the contract to maturity, she must deliver and sell AT&T stock for the price of ![]() in Chicago. Since each contract always has a buyer and a seller, then if the contracts are held to maturity there will always be a ‘short’ ready to deliver the underlying asset to the person holding the long position in the futures contract.

in Chicago. Since each contract always has a buyer and a seller, then if the contracts are held to maturity there will always be a ‘short’ ready to deliver the underlying asset to the person holding the long position in the futures contract.

Financial futures are written on financial assets (e.g. stock indices, currencies, T-bills, T-bonds) whereas commodity futures are written on, say, wheat, silver, oil, etc. The underlying asset in a futures contract, for example the stock of AT&T, is traded at the ‘spot price’ in the cash market, which in this case is the NYSE. The futures is a derivative security, because changes in futures prices are closely linked to changes in the spot/cash market price (of the underlying asset).

Futures markets can be used for speculation, hedging, or arbitrage. Because there is always a counterparty to a futures contract (i.e. Ms A is long, Ms B is short) then any gains by Ms A are accompanied by losses for Ms B – overall it is a zero sum game (ignoring transactions costs). However, for any individual trader on one side of the market (i.e. either long or short) there are potential cash gains and losses to be made.

Since futures contracts (unlike forward contracts) are traded on an exchange, there needs to be some standardisation of the contracts. Also, to minimise default risk, a clearing house tracks all trades and requires buyers and sellers of futures contracts to post collateral (e.g. cash, T-bills), known as a margin payment. This ‘good faith’ payment is used to compensate a trader if another trader defaults on the contract.

2.1.1 Standardisation

The futures exchange sets the size of each contract, the units of price quotation, minimum price fluctuations, the ‘grade’ and place for delivery, any daily price limits and margin requirements as well as opening hours for trading. For agricultural commodities, the type or grade is also fixed in the futures contract. For example, for corn the standardised grade is ‘No. 2 Yellow’ but other grades can also be delivered – for example ‘No 1. Yellow’ is deliverable for 1.5 cents per bushel more than ‘No. 2 Yellow’ because the quality is higher. The futures exchange sets the minimum contract size (e.g. delivery of 5,000 bushels of corn), delivery dates (e.g. specific dates in March, May, June, July, September, and December) and delivery arrangements (e.g. delivery only to towns A, B, and C).

For futures on financial assets such standardisation is easier. For example, a foreign exchange (FX) futures contract on the pound sterling (GBP) is rather a homogenous product and only the delivery dates, settlement price, and contract size need to be organised by the exchange. Some futures contracts are traded with maturity dates of only up to a year or two ahead but some contracts have much longer maturity dates. It depends primarily on the demand for such contracts by hedgers. For example, the Eurodollar futures contract is actively traded with maturities out to 15 years or more because these contracts are used by swap dealers to hedge their interest rate swap positions.

The size of the contract is important. If too small, speculators will not trade the contract because the transactions costs per contract may be relatively high but if the ‘size’ is too large, then hedgers will not be able to hedge relatively small amounts (e.g. the Eurodollar futures has a contract size of $1m and you cannot hedge $500,000 by using half a contract). The tick size and tick value should be easily understood by market participants. For example, the US T-bill futures contract has a contract size of $1m and a tick size of 1 basis point (i.e. one-hundredth of 1%) and a minimum price change (tick value) of $25. Hence, if the futures price changes from ![]() to

to ![]() , the value of one futures contract (on T-bills) changes by $25.

, the value of one futures contract (on T-bills) changes by $25.

As each contract has both a long and a short position, the total number of futures contracts outstanding either long or short, is called the open interest.

The way ‘open interest’ changes, assuming it starts at zero, is shown in Table 2.3. When trader-A (buyer) and trader-B (seller) first enter the market on day-1, then open interest increases by one (i.e. one long and one short). Similarly, for trader-C and trader-D, who increase open interest by three when they buy (= C) and sell (= D) three contracts on day-2. On day-3, trader-A, who is long one contract, sells her contract to trader D who is initially short three contracts – open interest falls by one. Trader-A is out of the market and trader-D is now only short two contracts. If on day-4 trader-C sells one contract to a ‘new’ trader-E then trader-C closes out one contract (and ends up with being long two contracts). But because trader-E enters the market, open interest is unchanged since trader-E has in effect taken the place of trader-C for this contract.

TABLE 2.3 Open interest

| Trading | Open interest | |

|

1 | |

|

4 | |

|

3 | |

|

3 | |

| Trader's final position | Long | Short |

| Trader-A | 0 | 0 |

| Trader-B | 0 | 1 |

| Trader-C | 2 | 0 |

| Trader-D | 0 | 2 |

| Trader-E | 1 | 0 |

| All traders | 3 | 3 |

2.2 FUTURES EXCHANGES AND TRADERS

In some futures markets, traders meet face-to-face in a pit, such as on the International Money Market (IMM) in Chicago and on the trading floor of the Chicago Board of Trade (CBOT) and, until 1999, on the London International Financial Futures Exchange (LIFFE), which has now merged and become the electronic trading platform, ‘NYSE-Euronext’. Traders in the pit indicate prices and deal sizes using hand signals and the system is known as open outcry.

All exchanges settle trades using computers but now more exchanges are moving away from open outcry and actual trades are conducted electronically. Some of these systems are ‘order driven’ whereby the buyers and sellers are ‘matched’ via a computer as, for example, on NYSE-Euronext. Futures trading is ‘global’. For example GLOBEX (which is owned by the CBOT and Reuters plc) provides an after-hours electronic futures trading system – ‘after-hours’ being from a US prospective. Note, however, that GLOBEX does not automatically match buyers and sellers and then automate the trades. It merely provides price information to traders.

On the IMM, floor traders can be either commission brokers called futures commission merchants (FCM) or ‘locals’. FCMs merely act as middlemen, buying and selling on behalf of clients and they make profits from their commission charges. Locals trade on their own account and hold a book (i.e. take positions in various contracts). Dual trading is also allowed.

2.2.1 Futures Trading

Public orders must be placed through a broker who will then contact a floor broker on the exchange. Trades are monitored by the clearing house (e.g. CME Clearing) and all floor traders must have an account with a member clearing firm. If your floor broker purchases a futures contract on your behalf, then you will have to pay the initial margin to the floor broker, who will then pay this into her clearing firm ABC. The seller may be a local or a broker acting on behalf of a customer ‘off the floor’. The seller of the futures also deposits the initial margin with her clearing firm XYZ. Both clearing firms ABC and XYZ each aggregate up their net positions from their customers and place a margin payment with the clearing house, who then guarantees both sides of the contract.

2.2.2 Trading Costs

In the US, brokers' commissions charged to the public include a payment for both buying and closing out the contract. However, commissions are very low, as are bid–ask spreads, making futures contracts very low cost instruments for hedging and speculation. The commissions, bid–ask spreads, and clearing fees for futures are usually less than those for forward contracts, which is perhaps not surprising since many forward contracts are tailor-made to suit the client. Delivery costs for ‘the short’ (if the contract goes to maturity) vary, depending on what is being delivered (e.g. ‘live cattle’ versus a cash settled futures contract on the S&P 500).

2.3 MARGINS AND MARKING-TO-MARKET

Margin payments provide financial protection in case one of the counterparties to the futures contract defaults. Consider a futures contract on oil (e.g. on ‘West Texas Intermediate WTI, Light, Sweet Crude Oil’). The contract size is for delivery of 1,000 barrels. If in Chicago the oil futures price is ![]() (per barrel) then the value of one futures contract is $98,000. If, for example, the futures price increases by $0.3 (e.g. from 98 to 98.3) the value of one long futures contract changes by $300 and the value of one short futures position decreases by $300.

(per barrel) then the value of one futures contract is $98,000. If, for example, the futures price increases by $0.3 (e.g. from 98 to 98.3) the value of one long futures contract changes by $300 and the value of one short futures position decreases by $300.

Assume the initial margin is $2,000 per contract and the maintenance margin is $1,500 per contract.1 The initial margin is not a payment for the futures contract. It is a ‘good faith’ deposit to ensure that the terms of the futures contract are honoured. Often a competitive interest rate is paid on the balance in the margin account, so funds in the margin account do not represent a cost. If the balance in the margin account falls below the maintenance margin of $1,500 per contract then the trader has to deposit extra funds known as the variation margin to restore the balance to the initial margin (of $2,000 per contract). The variation margin ensures that the balance in the margin account never becomes negative. As a ball-park estimate, the maintenance margin is set at around 75% of the initial margin.

The initial margin can be in cash but T-bills/bonds are often accepted (at 90% of their face value) and sometimes shares are accepted (at about 50% of their market value). The variation margin can usually only be paid in cash. Margin requirements are also referred to as ‘performance bonds’. The investor in the futures contract is allowed to withdraw any balance in the margin account in excess of the initial margin.

Suppose at 12 a.m. on 5 June Ms Long buys ![]() = 2 December-futures contracts on oil at

= 2 December-futures contracts on oil at ![]() and closes out the contracts 4 days later at 1 p.m. on 9 June by selling two December contracts at a price of

and closes out the contracts 4 days later at 1 p.m. on 9 June by selling two December contracts at a price of ![]() . Ms Long makes a profit on the two contracts of $600

. Ms Long makes a profit on the two contracts of $600 ![]() . Let us see how the margin account achieves the same result as the above simple ‘differences’ calculation.

. Let us see how the margin account achieves the same result as the above simple ‘differences’ calculation.

When Ms Long purchases (go long) one futures contract at $98, the initial face value of her futures position is $98,000. If Ms Long buys ![]() futures contracts, she pays an initial margin of

futures contracts, she pays an initial margin of ![]() – see Table 2.4.

– see Table 2.4.

TABLE 2.4 Margin account

Note: NF = 2 contracts, initial margin = $2,000 per contract, maintenance margin = $1,500 per contract. The first and last entries for ‘Futures price’ are actual trading prices – the rest are ‘settlement prices’ at the close of trading each day.

| Day/time | Futures price (value) per contract | Gain/loss per contract | Daily gains and losses NF = 2 | Balance in margin account | Margin call |

| Day-1, 2.10 p.m. | 98.0 ($98,000) | $4,000 | |||

| Day-1, Close | 97.9 ($97,900) | ($100) | ($200) | $3,800 | |

| Day-2, Close | 97.4 ($97,400) | ($500) | ($1,000) | $2,800 | $1,200 |

| Day-3, Close | 97.8 ($97,800) | $400 | $800 | $4,800 | |

| Day-4, 1 p.m. | 98.3 ($98,300) | $500 | $1,000 | $5,800 |

Suppose that by the close of day-1 the (‘settlement’2) futures price falls from ![]() to

to ![]() . The ‘long’ has a loss of $100 per contract since at the end of day-1 she can now only sell each futures contract for $97,900. The loss on two contracts is $200 and the balance in Ms Long's margin account is therefore reduced by $200 to $3,800. This is marking-to-market. The balance at the end of day-1 is above the maintenance margin of $3,000 (for two contracts).

. The ‘long’ has a loss of $100 per contract since at the end of day-1 she can now only sell each futures contract for $97,900. The loss on two contracts is $200 and the balance in Ms Long's margin account is therefore reduced by $200 to $3,800. This is marking-to-market. The balance at the end of day-1 is above the maintenance margin of $3,000 (for two contracts).

At the end of day-2 the futures price has fallen to $97.4 and the loss on two contracts is $1,000 so the value in the margin account is $2,800 which is below the maintenance margin of $3,000. The margin account must be made up to $4,000 (the initial margin) by the end of the next day (end of day-3), which requires a variation margin payment of $1,200. By the end of day-3, the futures price is 97.8, an increase of 0.4 which implies that the balance in the margin account is increased by $800, making a final balance of $4,800.

At 1 p.m. on day-4, the two futures contracts are closed out (sold) at 98.3 (to another futures trader) and Ms Long's margin account is credited with $1,000 giving a final balance of $5,800. The $5,800 is paid to Ms Long by the clearing house. Since Ms Long previously paid in $5,200 (=$4,000 initial margin + $1,200 variation margin), her profit over the 4 days is $600. This profit from the operation of the margin account is just the change in the futures price over the holding period of 4 days, that is, ![]() .3

.3

In the case of a price fall, Ms Long has losses deducted from her margin account and the clearing house credits the margin account of someone who has a short position (i.e. who has previously sold one futures contract). The opposite occurs for a rise in the futures price. A futures trader can withdraw (if she wishes) any balance in her margin account, over and above the initial margin (per contract).

2.3.1 Price and Position Limits

If the balance in the margin account falls below the maintenance margin, then the investor must top up her account (i.e. she pays a ‘variation margin’) to equal the initial margin by the end of the next day. If the investor does not do this, the broker closes out the position by selling/buying the contracts. Clearly it is possible for the futures price to fall (or rise) so dramatically over one day that the margin account is depleted. To prevent this happening the exchange sets daily price limits. If the price falls (or rises) in one day by as much as the ‘limit down’ (‘limit up’), then trading (usually) ceases for that day. These circuit breakers limit the daily payments/receipts to and from the margin account so that the balance in the margin account does not fall below zero and can be replenished before trading begins the next day. Often the initial margin is set equal to the value of the contract's daily price limit and therefore the initial margin can be small relative to the value of the futures contract.

The exchange also imposes position limits, that is the maximum number of contracts a speculator may hold (e.g. a maximum of y contracts with no more than z [< y] in any one delivery month). This prevents speculators from having undue influence on the market. Bona-fide hedgers are not subject to position limits.

2.3.2 Closing Out

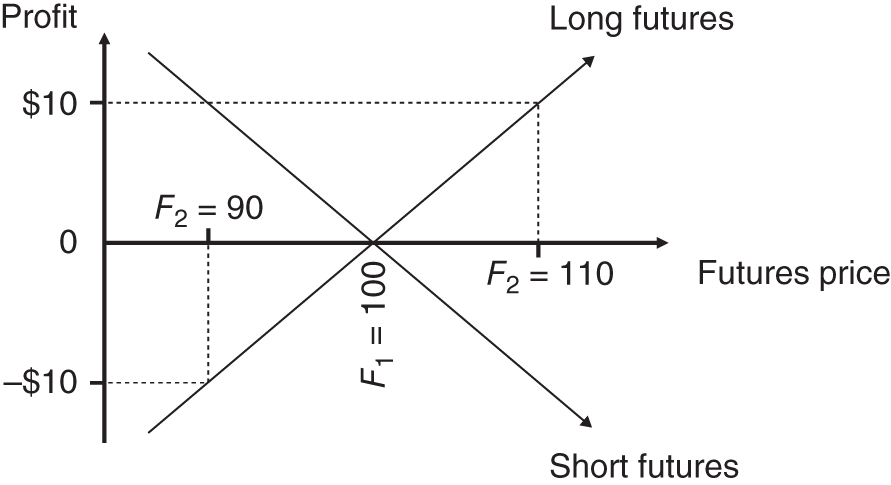

In practice most futures positions are closed out before maturity. You therefore make a gain or loss depending on the difference between the initial futures price ![]() and the futures price at which you close out the contract, say

and the futures price at which you close out the contract, say ![]() (Figure 2.1). Closing out the contract merely involves reversing your initial trade.

(Figure 2.1). Closing out the contract merely involves reversing your initial trade.

FIGURE 2.1 Speculation with futures

If in January Ms Long purchases a September-futures contract (on stocks) at ![]() in Chicago and in July she sells a September-futures contract at

in Chicago and in July she sells a September-futures contract at ![]() , the profit on the trade is

, the profit on the trade is ![]() . Also, by buying and then later selling the same September-futures contract, any delivery of the underlying asset to Ms Long is nullified. If you are long September-futures in January, then an increase in the futures price implies you make a profit when you close out – this is a positive relationship.

. Also, by buying and then later selling the same September-futures contract, any delivery of the underlying asset to Ms Long is nullified. If you are long September-futures in January, then an increase in the futures price implies you make a profit when you close out – this is a positive relationship.

If in January you buy (go long) a September-futures at ![]() and the futures price falls to

and the futures price falls to ![]() in July, then you make a loss of $10 (i.e. a profit of –$10). Again, this is a positive relationship – a fall in the futures price leads to a fall in profits. You bought for

in July, then you make a loss of $10 (i.e. a profit of –$10). Again, this is a positive relationship – a fall in the futures price leads to a fall in profits. You bought for ![]() and you close out by selling at

and you close out by selling at ![]() – a loss of $10.

– a loss of $10.

The profit on the long futures position ![]() is equal to the cumulative gain or loss incurred day by day, as the contract is marked-to-market. So, in practice, the profit accrues in daily instalments over the life of the futures contract. Although most futures contracts are closed out, it is the possibility of delivery which links the futures price to the underlying spot price (via riskless arbitrage) and arbitrage implies that the futures price in Chicago (over short time horizons) moves almost dollar-for-dollar with the spot price (in New York).

is equal to the cumulative gain or loss incurred day by day, as the contract is marked-to-market. So, in practice, the profit accrues in daily instalments over the life of the futures contract. Although most futures contracts are closed out, it is the possibility of delivery which links the futures price to the underlying spot price (via riskless arbitrage) and arbitrage implies that the futures price in Chicago (over short time horizons) moves almost dollar-for-dollar with the spot price (in New York).

Now consider an investor Ms Short who in January sells (shorts) a September-futures contract at ![]() (Figure 2.1). Suppose the futures price then falls to

(Figure 2.1). Suppose the futures price then falls to ![]() in July. She can buy back the contract in July (and hence close out her position) at the quoted futures price of

in July. She can buy back the contract in July (and hence close out her position) at the quoted futures price of ![]() . She initially sold at $100 and she buys back in July at $90 – making a profit of +$10. Conversely, if the futures price rises to

. She initially sold at $100 and she buys back in July at $90 – making a profit of +$10. Conversely, if the futures price rises to ![]() in July, then Ms Short would make a loss of $10 if she closed out. Hence for Ms Short there is a negative relation between her profit and the change in the futures price.

in July, then Ms Short would make a loss of $10 if she closed out. Hence for Ms Short there is a negative relation between her profit and the change in the futures price.

2.3.3 Delivery and Settlement

Although most futures are closed out before maturity it is important to understand the delivery process. The futures contract is referred to by its delivery month. The delivery period set by the Chicago exchange varies from contract to contract. For many contracts the delivery period is the whole month (but could also be for specific days in the delivery month).

The decision on when to deliver is made by the party with the short position. So, a person holding a short September wheat-futures can issue a notice of intention to deliver, to the clearing house. For commodities, the notice will contain the number of contracts to be delivered, the grade, delivery point and specific delivery date. The clearing house then selects someone with a long position in September wheat-futures and lets them know that they must accept delivery within the next few days. Selection of the long may be done randomly or by taking the ‘traders’ with the oldest outstanding long position. The long must accept the delivery notice but if the notice is ‘transferable’, she has about 30 minutes to find another person with a long position to accept the notice from them.

For ‘commodities’, delivery is usually in the form of a warehouse receipt and ‘the long’ then pays the most recent settlement price. The precise time and place for delivery is determined by the party with the short position. The long is then responsible for any ‘warehousing costs’ (e.g. for wheat, silver, gold) or in the case of livestock futures, care of the animals. Delivery of oil and natural gas is at a specific point along the ‘pipeline’ – for example, in the US at Cushing, Oklahoma for oil and at Henry Hub in Louisiana for natural gas.

The ‘first notice day’ is the first day on which the short can issue a notice to deliver. Hence a person with a long position should close out before the first notice day if she does not want to take delivery. The ‘last notice day’ is the last day the short can issue the notice to deliver. Trading in the futures contract usually ceases a few days before the last notice day.

Delivery (for non-cash settled contracts) is usually about a 3-day process. Two days before someone with a short position intends to make delivery, she notifies the clearing house. The next business day, the exchange selects the party with a long position to take delivery. On the third day, the delivery day, the short delivers the underlying asset and the long pays the short (and the deal is confirmed).

Some financial futures contracts involve the delivery of the underlying asset (e.g. T-bills, T-bonds) while others, such as stock index futures, are settled in cash. Often cash-settled contracts use the settlement price of the spot asset on the last trading day – the positions of the long and the short are then ‘closed out’ by the clearing house and the contract no longer exists. The settlement price may be the opening or closing price on the settlement day.

One of the key differences between forwards and futures is that forward contracts cannot be easily closed out. Usually Ms A can only close out her long forward contract (initially entered into with counterparty B) by selling her contract to Ms C. In general Ms B will have to agree the ‘new’ contract between Ms A and Ms C because of the credit risk to Ms B who is short the contract. In contrast, if Ms A has a long position in a ‘hog’ futures contract,4 then she can easily offset it by selling a new futures contract with the same delivery date. For example, if on 1 February Ms A purchased one September-futures on hogs at ![]() and she later sold one September-futures on hogs on 1 June for

and she later sold one September-futures on hogs on 1 June for ![]() , then Ms A makes a cash profit of $10 but there will be no delivery of hogs to Ms A in September. As far as Ms A is concerned this contract is now nullified.

, then Ms A makes a cash profit of $10 but there will be no delivery of hogs to Ms A in September. As far as Ms A is concerned this contract is now nullified.

2.3.4 Newspaper Quotes

An illustrative example of futures quotes for gold on 10 October (say) is given in Table 2.5. The size of the contract is for delivery of 100 troy oz of gold and the price is in US dollars per troy oz. There are various maturity dates. The nearby contract is the October-futures and the table shows contracts with maturities out to the next August.

TABLE 2.5 Futures quotes, 10 October, Gold (GC), 100 troy oz ($ per troy oz)

| Month | Open | High | Low | Settle | Change | Open interest |

| October | 1236.1 | 1236.5 | 1235.5 | 1237.4 | 4.6 | 633 |

| December | 1239.0 | 1246.5 | 1232.2 | 1243.1 | 4.4 | 299,488 |

| February | 1244.8 | 1252.3 | 1242.7 | 1249.4 | 4.4 | 33,161 |

| April | 1251.3 | 1251.3 | 1249.3 | 1255.5 | 4.5 | 18,513 |

| June | 1253.0 | 1262.1 | 1253.0 | 1261.6 | 4.5 | 18,037 |

| August | 1261.0 | 1267.6 | 1261.0 | 1267.4 | 4.5 | 18,244 |

The opening futures price (for the trade immediately after the opening bell), and the ‘high’ and ‘low’ daily futures prices during the trading day are given in columns 2 to 4. The fifth column (‘Settle’) gives the settlement price which is an average of prices just before the closing bell and the sixth column shows the change in the settlement price, since the previous day. The settlement price is used to calculate daily changes in margin requirements. For example, if between two trading days the settlement price for December-futures increases by $4.5 and an investor is long one gold futures contract (for 100 troy oz), she would have her margin account credited by $450 (= 100 × $4.5). The trader who is short the December futures would have her margin account debited by $450.

If we look down the column marked ‘Settle’ we see that on 10 October, the long-dated futures contracts on gold have a higher quoted futures price, than the more near-dated contracts. As we shall see in Chapter 3, this is due to interest costs and storage costs for gold, which both increase as the time to maturity of the futures contract increases.

Open interest is the number of futures contracts currently outstanding and most traders are currently holding the December contract with open interest of around 300,000 contracts (i.e. 300,000 trades who are long the December contract and 300,000 counterparties who are short the December contracts). On 10 October the far-dated contracts, with maturity from February onwards, are not very actively traded. This is probably because investors who wish to hedge their current holdings of (spot) gold are more interested in hedging over the October to December period, rather than over longer horizons.

2.3.5 Types of Traders

Some futures traders are scalpers, who hold their positions for less than a few minutes. Day traders hold their positions for less than a day, for fear of overnight news changing the price by a large amount. Position traders may hold their positions much longer since they base their investment decisions on the economic fundamentals driving the price of the underlying asset. Spread traders buy one futures contract and simultaneously sell another futures contract in the hope of making a profit. For example, in an intracommodity spread the trader buys a contract with one expiry month and sells an otherwise identical contract with a different expiry month, hoping to benefit from the differential move in the two futures prices. An intercommodity spread consists of a long position in a contract on one commodity (e.g. coffee) and a short position in a contract on a different commodity (e.g. cocoa) where the speculator is trying to exploit an ‘abnormal’ difference between the two prices, which she hopes will be corrected in the near future.

Floor brokers who have a seat on the exchange merely buy and sell futures contracts on behalf of their customers and usually earn a commission on each trade. They do not hold a book and they are not obliged to ‘make a market’ in the futures.

Instructions to your broker might involve a market order which is for immediate execution at the best available price. A limit order specifies a maximum price for a purchase and a minimum price to sell. The limit order may be a day order (i.e. it is only valid until the end of the day) or a good-till-cancelled order. If you already hold a futures contract you may institute a stop-loss order, which instructs your broker to sell the futures if the price falls a fixed amount below the current price.

2.4 SUMMARY

- A futures contract is marked-to-market, so its value changes each day.

- The clearing house keeps track of all trades and sets the amounts for the initial margin and the maintenance margin. If the amount in the trader's margin account falls below the maintenance margin, additional variation margin payments have to be made to bring the balance in the margin account up to the ‘initial margin’. This minimises counterparty (credit) risk.

- The clearing house sets the terms for each futures contract, such as the contract size, tick value, delivery dates, the precise definition of the settlement price and the margin requirements.

- Trading can be via open outcry in a trading pit (e.g. in Chicago) but there has been a major shift towards electronic trading which is 24 hours a day (e.g. on the CME-Globex platform).

EXERCISES

Question 1

Explain how a long one-year forward contract on a stock, entered into at F0 = $100 can be used for speculation. Assume the forward contract is held to maturity.

Question 2

What are the key differences between forward contracts and futures contracts?

Question 3

Briefly explain ‘open interest’ and ‘trading volume’ for futures markets.

Question 4

Explain an ‘initial margin’ of $5,000 (per futures contract) and a ‘variation margin’ of $2,000. Why are these concepts useful?

Question 5

On Monday, you are already long 100 contracts at a settlement price of $50,000 per contract. Next day (Tuesday) at 11 a.m. you acquire an additional 20 contracts at a price of $51,000 per contract. The initial margin is $2,000 per contract. The settlement price at the end of Tuesday is $52,000 per contract. By how much does the margin account change between Monday and Tuesday?

Question 6

At the end of day-1 you purchase 100 contracts of the September-futures at a settlement price of ![]() per contract. The initial margin on any contracts you initially purchase is $2,000 per contract. Hence, at the end of day-1 you have paid $200,000 into your margin account. On day-2, at 11 a.m. you acquire an additional 20 (September) contracts at a price of F2= $51,000 per contract. The settlement price at the end of the day is F3= $50,200 per contract.

per contract. The initial margin on any contracts you initially purchase is $2,000 per contract. Hence, at the end of day-1 you have paid $200,000 into your margin account. On day-2, at 11 a.m. you acquire an additional 20 (September) contracts at a price of F2= $51,000 per contract. The settlement price at the end of the day is F3= $50,200 per contract.

-

- What is the net gain or loss on the value of all of your contracts at the end of day-2? Express this gain or loss algebraically.

- What happens if you close out all your contracts at the end of day-2 at the settlement price of £50,200? What is the value of your margin account at the end of day-2?

Question 7

You buy stock index futures SIF at an index price of F = 452 at 11 a.m. on 1 August. The initial margin is $9,000 and the maintenance margin is $6,000. You close out the contract at 11 a.m. on 4 August at 450. The settlement prices at the end of the day on 1, 2, 3 August are 453, 430, 445. You do not withdraw any excess cash out of your margin account.

What is the profit (loss) on the SIF contract? Construct a table to show inflows and outflows from the margin account. (Assume the value of an index point on the futures contract is $250.)

NOTES

- 1 These figures are illustrative. For crude oil futures the current maintenance margin is around $2,000 to $2,500, depending on the contract. The initial margin on CME is 110% of the maintenance margin.

- 2 The amount in the margin account is recalculated at the end of each day. The futures price used to calculate the value of the futures position is the average price of the last few trades of the day and is known as the ‘settlement price’.

- 3 This ignores any daily interest earned on the margin account.

- 4 A hog is a type of pig.