CHAPTER 33

Interest Rate Swaps

Aims

- To show how plain vanilla interest rate swaps can be used to convert uncertain future floating-rate interest cash flows into known fixed-rate cash flows (or vice versa).

- To examine the role of swap dealers, settlement procedures, pricing schedules and the termination of swap agreements.

- To demonstrate how cash payoffs in the swap are determined.

- To demonstrate the principle of comparative advantage – the source of gains in a swap.

Swaps are privately arranged contracts (i.e. OTC instruments) in which parties agree to exchange cash flows in the future according to a prearranged formula. Swap contracts originated in about 1981. The largest market is in interest rate swaps but currency swaps are also widely used.

The most common type of interest rate swap is a plain vanilla fixed-for-floating rate swap. Here one party agrees to make a series of fixed interest payments to the counterparty, and to receive a series of payments based on a variable (floating) interest rate (LIBOR). The interest payments are based on a stated notional principal of say ![]() , but only the interest payments are exchanged each period, not the principal value – hence the use of ‘notional’. The payment dates, day-count convention, maturity of the swap, and the floating rate to be used (usually LIBOR) are also determined at the outset of the contract. In a plain vanilla swap ‘the fixed rate payer’ knows exactly what the (dollar) interest payments will be on every payment date but the floating rate payer does not.

, but only the interest payments are exchanged each period, not the principal value – hence the use of ‘notional’. The payment dates, day-count convention, maturity of the swap, and the floating rate to be used (usually LIBOR) are also determined at the outset of the contract. In a plain vanilla swap ‘the fixed rate payer’ knows exactly what the (dollar) interest payments will be on every payment date but the floating rate payer does not.

Why are swaps so popular? The first reason is that swaps can be used to reduce the cost of borrowing. Suppose Microsoft wants a fixed-rate loan with a principal ![]() . Rather than taking out a fixed-rate loan directly with Citibank at 6.6% p.a. (say), Microsoft may end up paying a lower fixed payment, if it obtains its fixed-rate loan indirectly.

. Rather than taking out a fixed-rate loan directly with Citibank at 6.6% p.a. (say), Microsoft may end up paying a lower fixed payment, if it obtains its fixed-rate loan indirectly.

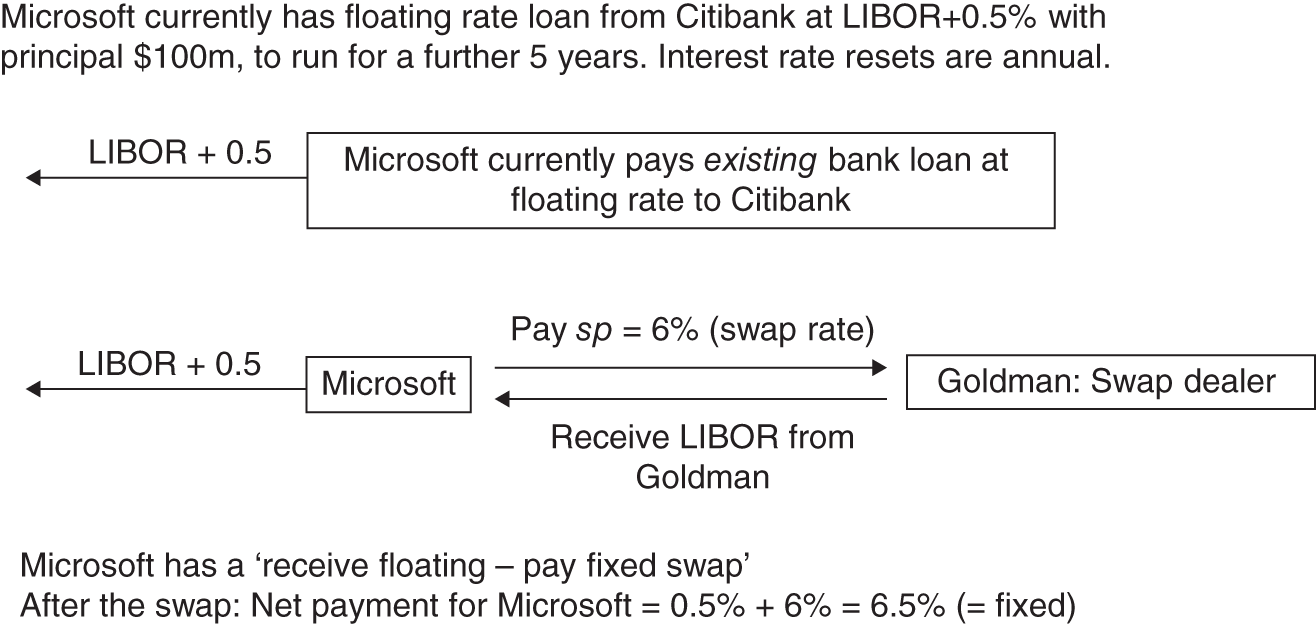

Surprisingly, Microsoft first takes out what it does not want – a floating-rate loan at LIBOR+0.5% with Citibank (Figure 33.1). Then Microsoft goes to a swap dealer (e.g. Goldman Sachs) and agrees to swap LIBOR receipts for fixed rate payments. Microsoft agrees to receive floating rate (LIBOR) from Goldman and to pay Goldman a fixed rate of say 6%, on a (notional) principal of $100m in the swap. The fixed rate ![]() is the swap rate.

is the swap rate.

FIGURE 33.1 Interest rate swap

The LIBOR receipts from Goldman are simply passed on to Citibank. Effectively Microsoft now has a fixed-rate loan at 6.5% (rather than at 6.6%, if Microsoft had gone directly for a fixed rate loan from Citibank). The lower fixed loan rate via the swap occurs because of the principle of comparative advantage (see Appendix 33). It probably arises because of ‘frictions’ in credit markets. There may be an element of oligopoly amongst lending institutions or the market between different banks in different countries is fragmented, so that credit spreads on direct borrowing at fixed rates are relatively high. Swaps may then provide a method of circumventing this problem, providing a net gain to all parties in the swap (assuming no one defaults).

It may be immediately obvious to some readers that an interest rate swap is (analytically) nothing more than a series of forward rate agreements (FRAs), to exchange cash flows based on a floating interest rate in exchange for cash flows at a fixed rate, at various predetermined dates in the future. Since the swap is equivalent to a series of FRAs (or interest rate forward contracts) then what swaps offer is lower transactions costs than a strip of FRAs. Indeed, although the market in FRAs is liquid (competitive) at short horizons of up to 1–2 years, the swaps market is liquid at both short and long horizons out to 20–30 years.

The intermediaries in a swap transaction are usually banks who act as swap dealers. They are usually members of the International Swaps and Derivatives Association (ISDA) which provides some standardisation in swap agreements via its master swap agreement which can then be adapted where necessary, to accommodate most customer requirements.

Swap dealers make profits via the bid–ask spread on the (fixed) swap rate and might also charge a small brokerage fee. Swap dealers take on many different swaps from many different counterparties but they will generally end up with a net open position (i.e. net payments or receipts at a floating rate). They usually hedge this position using interest rate (Eurodollar) futures contracts (and sometimes interest rate options).

33.1 USING INTEREST RATE SWAPS

Another reason you might use an interest rate swap is to remove existing interest rate risk. Suppose Microsoft has an existing long-term bank loan with Citibank which has been running for some time, on which it pays LIBOR+0.5%. Assume Microsoft now becomes worried about rising interest rates in the future, so it wants to switch to a fixed rate loan.

It could go back to Citibank and negotiate to switch from a floating rate loan to one where it pays known fixed (dollar) interest payments every year. But renegotiating loan contracts for large corporations is a tricky and expensive proposition – think of all those lawyers' fees when the covenants in the loan contract are altered, not to mention lengthy negotiations before the new loan is issued. It is easier and cheaper to keep the existing floating rate loan with Citibank but undertake a swap. This will result in Microsoft ending up with what it wants – namely, to have fixed known dollar interest payments. We have already dealt with this situation in Figure 33.1.

By using the swap, Microsoft has transformed an initial floating rate loan with Citibank into fixed rate payments at 6.5%. Microsoft effectively now has the equivalent of a fixed rate loan. If the maturity of the swap ends when the bank loan terminates and is for the same principal amount, and tenor, then Microsoft will have known fixed interest payments over the rest of the life of the loan. In a plain vanilla interest rate swap the floating rate is usually ‘LIBOR-flat’ (i.e. without a spread) and the swap dealer will then determine the appropriate fixed rate to charge in the swap.

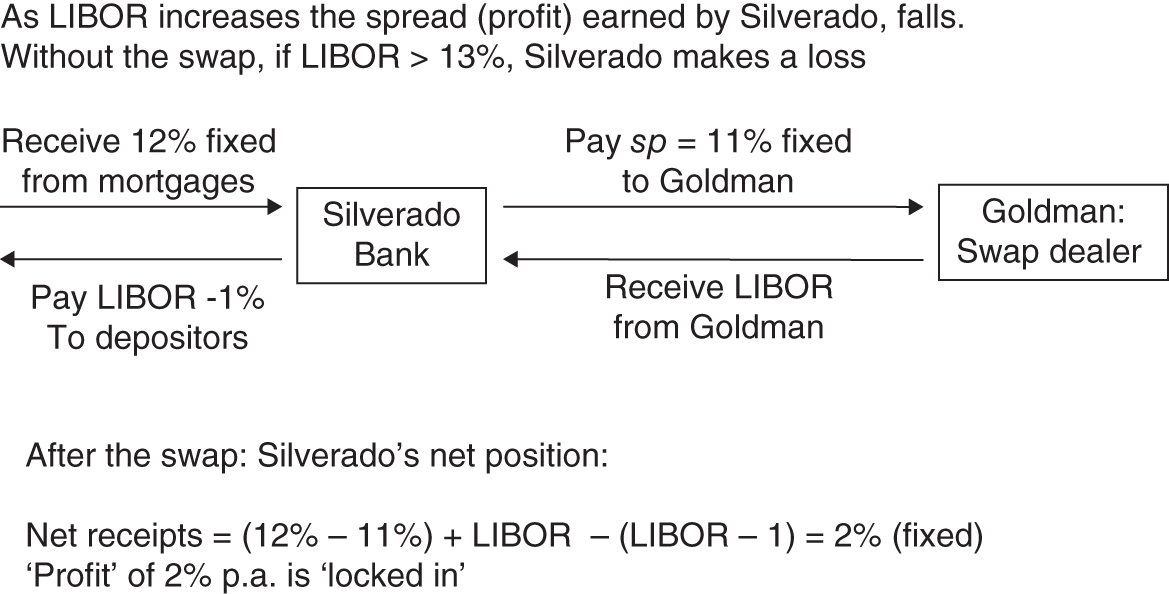

Next, let us see how a swap can be used to reduce interest rate risk for a financial intermediary like a bank or Savings and Loan Association (‘Building Society’ in the UK and Savings Bank in Europe), so that the financial intermediary can ‘lock in’ a profit over future years. Assume Silverado bank has fixed rate receipts from its existing loans or housing mortgages, at say 12%, but raises much of its finance in the form of short-term floating rate deposits, at say LIBOR-1% (Figure 33.2). Income paid on deposits varies as market interest rates vary and this is a source of risk for the financial intermediary.

FIGURE 33.2 Interest rate risk of Silverado Bank

If the deposit rate is LIBOR-1% and LIBOR currently equals 11% the bank pays out 10% to depositors. But if its fixed rate mortgages and loans earn 12%, the financial intermediary currently earns a profit (maturity spread) of 2% p.a. However, the danger is that if LIBOR rises by more than 2% the S&L will make a loss – the source of the risk is future increases in LIBOR.

Silverado Bank can remove this LIBOR risk if it enters into a swap with Goldman to receive LIBOR and pay a fixed rate. Suppose Goldman sets the fixed rate payment in the swap at ![]() . By entering into the swap Silverado is protected from any future rises in LIBOR rates. It now effectively has net fixed rate receipts of 2%, which is its fixed (risk-free) profit margin.

. By entering into the swap Silverado is protected from any future rises in LIBOR rates. It now effectively has net fixed rate receipts of 2%, which is its fixed (risk-free) profit margin.

As discussed above, one reason for undertaking a swap is that some firms find it cheaper to borrow at say floating rates and then use a swap to create the effective fixed rate payments that they really want. This cost saving provides the financial incentive behind the expansion of the swaps market. An example of a swap agreement is shown in Finance Blog 33.1.

33.2 CASH FLOWS IN A SWAP

Suppose on 15 March-01 ![]() ,1 Microsoft enters into a ‘receive-float, pay-fixed’ swap – this is referred to as a ‘long position’ in the swap (by convention). Suppose the swap rate

,1 Microsoft enters into a ‘receive-float, pay-fixed’ swap – this is referred to as a ‘long position’ in the swap (by convention). Suppose the swap rate ![]() on a notional principal of

on a notional principal of ![]() , with a 6-month tenor and the swap ends on 15 March-04.

, with a 6-month tenor and the swap ends on 15 March-04.

Floating rate payments are determined by LIBOR at the beginning of each (6-month) reference period but the actual cash payment occurs 6 months later. Hence the known value for LIBOR on 15 March-01, ![]() is used to determine the floating cash payment on the 15 September-01. Similarly, whatever LIBOR turns out to be on 15 September-01 will determine the floating cash payment on 15 March-02 etc.

is used to determine the floating cash payment on the 15 September-01. Similarly, whatever LIBOR turns out to be on 15 September-01 will determine the floating cash payment on 15 March-02 etc.

Day-count conventions differ, but we use the so-called ‘money-market’ day-count convention for the floating leg of the swap which is ‘actual/360’. Hence we have ![]() and

and ![]() = actual number of days between each repayment date. For a swap with a 6-month tenor actual

= actual number of days between each repayment date. For a swap with a 6-month tenor actual ![]() would be around 180 but might vary slightly for each 6-month period. The first floating payment (on 15 September-01, at

would be around 180 but might vary slightly for each 6-month period. The first floating payment (on 15 September-01, at ![]() ) is:

) is:

The cash flows for the fixed-leg ![]() are determined by the (fixed) swap rate. Hence,

are determined by the (fixed) swap rate. Hence, ![]() where

where ![]() is the swap rate and

is the swap rate and ![]() is the tenor in the fixed-leg. The convention for determining

is the tenor in the fixed-leg. The convention for determining ![]() for the fixed leg is set out in the swap contract – we assume the convention is

for the fixed leg is set out in the swap contract – we assume the convention is ![]() for each 6-month period in the fixed leg of the swap.2 Hence the fixed cash flows are (always):

for each 6-month period in the fixed leg of the swap.2 Hence the fixed cash flows are (always):

The net receipts for the long position (receive floating-pay fixed) in the swap, on 15 September-01 is:

Similarly the net receipts on 15 March-02 are determined by the out-turn LIBOR rate on 15 September-01 of 7% and the 181 days between September-01 and March-02:

On 15 March-01 we do not know what the LIBOR rates will turn out to be on any of the reset dates ![]() , until we actually reach these dates in ‘real time’. But Table 33.1 assumes a set of out-turn LIBOR rates and calculates the resulting ex-post payments in the swap – that is, the swap payments that ensue after we observe the out-turn values for LIBOR.

, until we actually reach these dates in ‘real time’. But Table 33.1 assumes a set of out-turn LIBOR rates and calculates the resulting ex-post payments in the swap – that is, the swap payments that ensue after we observe the out-turn values for LIBOR.

TABLE 33.1 Swap: cash pay-outs (ex-post)

Note: Last reset date 15 March-01. First payoff in the swap is based on rates on 15 March but cash payment does not occur until 15 September.

| Notional principal | 100,000,000 | |||||

| Swap rate | 6 | |||||

| Days in years (swap convention) | 360 | |||||

| Tenor for fixed leg (days) | 180 | |||||

| Tenor for floating leg is ‘actual/360’ | ||||||

| Date | Days | LIBOR | LIBOR cash flow | Fixed cash flow | Receive float, pay fixed | |

| 15-Mar-01 | 6.5% | |||||

| 15-Sep-01 | 184 | 7% | 3,322,222 | 3,000,000 | 322,222 | |

| 15-Mar-02 | 181 | 6.5% | 3,519,444 | 3,000,000 | 519,444 | |

| 15-Sep-02 | 184 | 6.25% | 3,322,222 | 3,000,000 | 322,222 | |

| 15-Mar-03 | 181 | 5.75% | 3,142,361 | 3,000,000 | 142,361 | |

| 15-Sep-03 | 184 | 5.25% | 2,938,889 | 3,000,000 | −61,111 | |

| 15-Mar-04 | 182 | 2,654,167 | 3,000,000 | −345,833 | ||

33.3 SETTLEMENT AND PRICE QUOTES

Take the case of a US swap dealer who wishes to set the swap rate on a 10-year swap with the floating rate based on 6-month LIBOR (Table 33.2). She will have an indicative pricing schedule (for that day) where the fixed rate will be based on the yield on current 10-year Treasury notes (bonds). In fact this will usually be the par bond yield plus a spread.

TABLE 33.2 Indicative pricing schedule for swaps

| Maturity | Current T-bond rate | Bank pays fixed | Bank received fixed |

| 5 years | 1.5% | 5-year T-bond + 5 bp | 5-year T-bond + 10 bp |

| 10 years | 2.7% | 10-year T-bond + 6 bp | 5-year T-bond + 12 bp |

| 20 years | 3.4% | 20-year T-bond + 8 bp | 5-year T-bond + 16 bp |

For example on a 10-year swap, if the swap dealer agrees to pay fixed (to counterparty-A) and receive floating then she will quote ![]() = 2.76% (= 2.7 + 6 bps, swap spread) and receive 6-month LIBOR-flat. The swap spread reflects the ‘normal’ credit risk as perceived by the swap dealer. Notice that no floating rates appear in the pricing schedule of Table 33.2 since the floating rate is understood to be 6-month LIBOR flat.3

= 2.76% (= 2.7 + 6 bps, swap spread) and receive 6-month LIBOR-flat. The swap spread reflects the ‘normal’ credit risk as perceived by the swap dealer. Notice that no floating rates appear in the pricing schedule of Table 33.2 since the floating rate is understood to be 6-month LIBOR flat.3

The dealer will eventually hope to match the pay-fixed deal with an offsetting swap (from another counterparty-B) to receive-fixed (on the same notional principal and tenor) at 2.82% (= 2.7 + 12bps) – thus obtaining 6 bps bid–ask spread as profit. In our above stylised example, once the swap dealer finds counterparty-B, then she is perfectly hedged with certain net receipts of 6 bps (i.e. the mismatch risk is eliminated).

However, it may be difficult for the swap dealer to find a counterparty-B who has exactly the ‘reverse wishes’ of A. For example, if the maturity of A's swap is say 5 years but B will only enter into the swap for 3 years, then the swap dealer is a net floating rate receiver in years 4 and 5 and is subject to interest rate risk, in the last 2 years of the swap. She may then initially hedge her mismatched swaps book using (Eurodollar) futures contracts which mature in 4 years and 5 years, respectively.

The bid–ask spread reflects several factors, namely the degree of competition between dealers, the risk in (temporarily) holding a net open position on one leg of the swap deal, and a swap dealer's current inventory position of being either net long or short in the fixed (or floating legs) of all its outstanding swaps (i.e. the overall position of its swap book).

The bid–ask spreads on interest rate swaps in various currencies are given in Table 33.3. All the fixed rates are quoted against the appropriate LIBOR rate (usually 3 months or 6 months). As you can see the bid–ask spreads are rather small, reflecting the high degree of competition and liquidity in the swaps market.

TABLE 33.3 Swap rates (FT)

| Oct 26 | Euro | £ | US$ | |||

| Bid | Ask | Bid | Ask | Bid | Ask | |

| 1 year | 1.38 | 1.43 | 0.82 | 0.85 | 0.37 | 0.40 |

| 5 year | 2.13 | 2.18 | 2.10 | 2.15 | 1.47 | 1.50 |

| 10 year | 2.78 | 2.83 | 3.18 | 3.23 | 2.67 | 2.70 |

| 20 year | 3.13 | 3.18 | 3.74 | 3.82 | 3.41 | 3.44 |

| 25 year | 3.06 | 3.11 | 3.79 | 3.92 | 3.52 | 3.55 |

| 30 year | 2.94 | 2.99 | 3.80 | 3.93 | 3.58 | 3.61 |

33.4 TERMINATING A SWAP

Suppose a swap agreement has been in existence for some time and the current value of the swap to Microsoft who receives LIBOR and pays fixed, is $1.2m and therefore the value to the swap dealer (Goldman) is ![]() . (We will see how the mark-to-market value of the swap of $1.2m is calculated in a later chapter.) Microsoft can terminate the swap by sale, assignment or buy-back.

. (We will see how the mark-to-market value of the swap of $1.2m is calculated in a later chapter.) Microsoft can terminate the swap by sale, assignment or buy-back.

In a sale, Microsoft simply finds a third party (e.g. Apple) to take over the fixed payments and LIBOR receipts (from Goldman) and Microsoft sells the swap (to Apple) for $1.2m. Alternatively, if the value of the swap to Microsoft had been –$1.4m (say) then Microsoft would have paid Apple $1.4m to take on the swap. The swap dealer Goldman would have to approve the use of any third party in the deal (i.e. Apple) because of credit risk.

Microsoft could use a buy-back whereby Goldman would pay $1.2m to Microsoft and the swap is terminated. Finally, Microsoft could undertake a reversal, that is enter a new swap where the cash flows exactly offset the cash flows in the original swap – the new swap (say with Morgan Stanley) will be a receive fixed-pay float with the same maturity, tenor, and notional principal as the original swap with Goldman.

33.5 COMPARATIVE ADVANTAGE

Interest rate swaps are undertaken because there are net reductions in the cost of borrowing for both parties to the swap. The swap dealer can also share in some of these gains. However, to keep things simple assume only two parties in the swap A and B.

A wishes to end up borrowing $10m at a floating rate for 5 years

and

B wishes to end up borrowing $10m at a fixed rate for 5 years.

The rates offered to A and B are shown in Table 33.4. ‘A’ has an absolute advantage in both markets since it can borrow at both floating and fixed rate at a lower cost than B (probably because B has a lower credit rating than A). Nevertheless, there is a net gain to both parties if they enter a swap. First look at the total cost to A and B if they directly borrow in their preferred form (i.e. A at floating and B at fixed) or non-preferred form (i.e. A at fixed and B at floating)

- Total cost to A and B of direct borrowing in ‘preferred form’

TABLE 33.4 Bank borrowing rates facing A and B Fixed Floating Company-A

Company-B

Absolute difference (B – A)

Net comparative advantage or ‘quality spread differential’

B has comparative advantage in borrowing at a floating rate. Hence B borrows from the bank at a floating rate. - Total cost to A and B if they borrow in ‘non-preferred form’

Hence the total cost is lower if they initially borrow in their non-preferred form:

Although there is a reduction in total cost using strategy (2), it results in A and B not having their preferred form of borrowing. However, a swap provides the mechanism to achieve their preferred form of borrowing and it has the advantage of lowering the overall cost of borrowing for both parties.

Looking at the overall gain in a slightly different way (Table 33.4), the key element is that B has comparative advantage when borrowing in the floating rate market, while A has comparative advantage when borrowing in the fixed rate market. (Comparative advantage is used in international trade theory to help explain why the UK exports some wine to France, even though the latter has an absolute cost advantage in producing wine.)

B has comparative advantage when borrowing in the floating rate market because B pays only 0.7% more than A does, whereas B pays (a larger) 1.2% more than A in the fixed rate market. (If you like, B pays ‘less more’ in the floating market than in the fixed rate market.)

B initially borrows floating and A borrows fixed. They then enter into a swap agreement whereby B agrees to pay A at a fixed rate and A pays B at a floating rate, so they both ultimately achieve their desired type of borrowing (i.e. B ends up paying fixed and A floating). A swap is advantageous to both parties if the net comparative advantage or quality spread differential is positive.

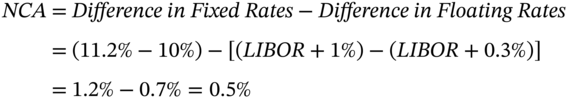

Net comparative advantage / Quality spread differential

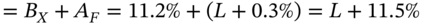

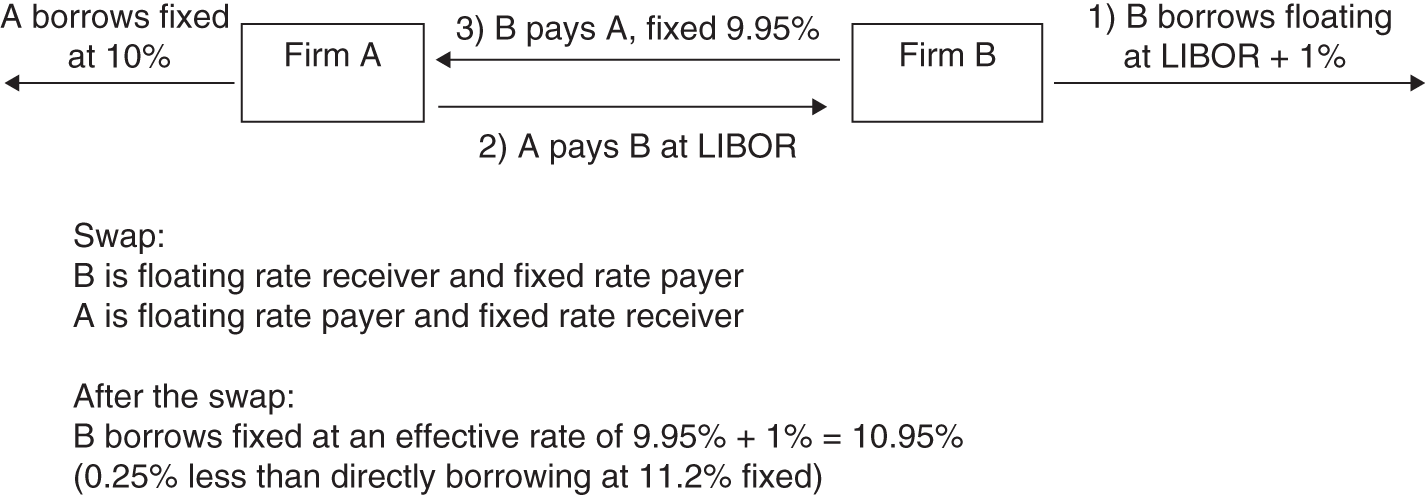

The 0.5% is the total gain from the swap, which is available to A and B. As long as A and B get some gain they will willingly enter the swap. We arbitrarily assume that the gain of 0.5% is split equally (0.25%) between A and B. (This split will depend on the relative bargaining power of A and B.) B has a comparative advantage in the floating rate market and hence issues $10m floating rate debt at LIBOR + 1% while A issues fixed rate debt at 10% (Figure 33.3).

FIGURE 33.3 Interest rate swap (between A and B)

Here's how we work out the figures in the swap (which are the cash flows between A and B in Figure 33.3). We initially consider the swap from B's point of view (who ultimately wants to borrow fixed) and expects to gain 0.25% overall. We will find that this ensures that A also achieves a gain of 0.25%. This is what happens to B:

- B initially borrows ‘direct’ from a bank at LIBOR + 1% (in which it has NCA)

- B in ‘leg1’ of the swap agrees to receive LIBOR

- Net payments by B so far are 1% (fixed)

- But B must end up with a gain of 0.25%, hence

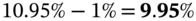

- Hence in ‘leg 2’ of the swap B must pay fixed at

.

.

Out-turn after swap for cash flows of B:

B initially borrows at LIBOR from a bank and in the swap, receives floating and pays fixed:

- B pays LIBOR + 1% on its bank loan

- B receives LIBOR from A

- B pays 9.95% fixed to A.

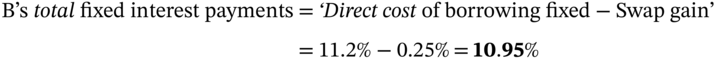

Hence, the net result is that B ends up paying 10.95% fixed (= 9.95% + 1%) even though it started out with a LIBOR bank loan. Although B pays 10.95% fixed, this is 0.25% less than if it went directly to the bank and borrowed at the rate of 11.2% fixed (Table 33.4). Does the above also allow A to gain 0.25 from the swap? The cash flows for A are:

Out-turn after swap for cash flows of A:

Initially ‘A’, takes out a fixed rate bank loan and in the swap receives fixed and pays floating:

- ‘A’ pays 10% fixed on its bank loan

- ‘A’ receives 9.95% fixed from B

- ‘A’ pays LIBOR to B.

Hence ‘A’ ends up paying LIBOR + 0.05% (= LIBOR + 10% – 9.95%). ‘A’ has converted its fixed interest bank loan into a net floating rate payment. Also A's floating rate payment of LIBOR + 0.05% is 0.25% less than it would pay if it borrowed directly from the bank at LIBOR + 0.3% (see Table 33.4).

Hence in the swap, A agrees to pay B at LIBOR and B agrees to pay A fixed at 9.95% (Figure 33.3). The overall payments and receipts are:

- B takes out a bank loan of $10m at LIBOR + 1%

- ‘A’ takes out a bank loan of $10m at 10% fixed

- In the swap ‘A’ agrees to pay B at LIBOR on a notional $10m and

- B agrees to pay ‘A’ at 9.95% fixed, on notional $10m.

Both A and B gain by 0.25% each, compared with borrowing directly in their preferred form from the bank. It can be shown (but it is tedious) that if we put a swap dealer in the ‘middle’, who deals with both A and B then all three parties, A, B, and the swap dealer can each have a share in the 0.5% total gain (see Appendix 33).

33.6 SUMMARY

- Swap contracts allow one party to exchange periodic cash flows with another party. They are over-the-counter OTC instruments.

- A plain vanilla interest rate swap involves one party exchanging fixed interest payments for cash flows determined by a floating rate (LIBOR). The notional principal in an interest rate swap is not exchanged.

- Swaps enable a company with a bank loan at floating rates to effectively switch this to a fixed rate (or vice versa) – hence a swap can be used to eliminate interest rate risk of future cash flows.

- Swap dealers earn profits on the bid–ask spread of the swap deal.

- One reason for swaps is that it may be cheaper for a company to borrow at say floating and use a swap to convert this to a fixed rate loan, rather than to directly obtain a fixed rate loan from its correspondent bank.

- The principle of comparative advantage allows all the parties to the swap to obtain their desired cash flows (fixed or floating), at a lower cost than borrowing directly in their preferred form.

APPENDIX 33: COMPARATIVE ADVANTAGE WITH SWAP DEALER

We use the same figures as in the text which are reproduced here in Table 33.A.1.

TABLE 33.A.1 Bank borrowing rates facing A and B

| Fixed | Floating | |

| Company-A |

|

|

| Company-B |

|

|

| Absolute difference (B – A) |

|

|

| Net comparative advantage or ‘quality spread differential’ |

B has comparative advantage in borrowing at a floating rate. Hence B borrows from the bank at a floating rate. |

|

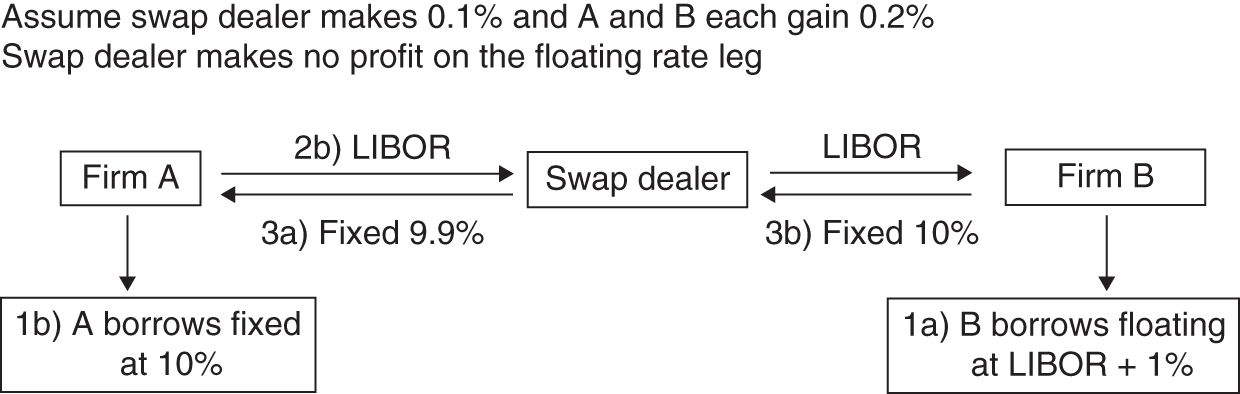

Assume that the swap dealer takes part of the total gain of 0.5%. In Figure 33.A.1 the swap dealer breaks even on the floating rate, since she pays out and receives LIBOR. On the fixed leg the swap dealer receives 10% but only pays out 9.9%, which provides an overall gain of 0.1% for the swap dealer.

Figure 33.A.1 Swap dealer

Cash Flows A

‘A’ initially takes out a fixed rate bank loan and in the swap receives fixed and pays floating

- ‘A’ pays 10% fixed on the bank loan (as Table 33.A.1)

- ‘A’ receives 9.9% fixed from the swap dealer and

- pays LIBOR to the swap dealer.

The net effect is that A pays LIBOR + 0.1%, which is 0.2% less than going directly to the floating rate loan market. From Figure 33.A.1 it is easy to work out B's position.

Cash Flows B

B initially takes out a bank loan at LIBOR and in the swap receives floating and pays fixed

- B pays LIBOR + 1% on its bank loan (as Table 33.A.1)

- B receives LIBOR from the swap dealer and

- B pays 10% fixed to the swap dealer.

The net effect is that B pays 11% fixed (which is 0.2% better than borrowing directly at a fixed rate from its correspondent bank). The swap dealer gains 0.1% on the difference between its receipts and payments on the fixed legs of the two swaps. Note that the swap dealer is subject to potential default risk since either A or B could default, yet the swap dealer has to honour its commitment to the other party. Also note that LIBOR in the above example can take on any value and the swap will still be worthwhile to all parties – so they will willingly enter the swap.

EXERCISES

Question 1

You have a floating rate bank loan (at LIBOR plus a spread). Why might you use an interest rate swap?

Question 2

What is a forward rate agreement (FRA) and how does it relate to a plain vanilla interest rate swap?

Question 3

You are a swap dealer. What is the meaning of the term ‘warehousing swaps’?

Question 4

Explain the difference between credit risk and market risk with reference to interest rate swaps. How can the market risk of interest rate swaps be hedged?

Question 5

The notional principal in a ‘pay-fixed, receive-floating’ interest rate swap with 3 further payments is $20m. The fixed rate payer pays 11% p.a. and the floating rate payer, pays LIBOR. Payments in the swap are every 90 days. Today at time t, immediately after a payment date, LIBOR is 11.5% p.a. The LIBOR rates at ![]() ,

, ![]() and

and ![]() , actually turn out to be 10.5% p.a., 10.2% p.a. and 9.6% p.a., respectively.

, actually turn out to be 10.5% p.a., 10.2% p.a. and 9.6% p.a., respectively.

Show the schedule of actual payments in the swap. Assume actual/365 day-count convention for all interest rates.

Question 6

Consider the following loan rates facing firms A and B.

| Fixed | Floating | |

| Firm-A | 10% p.a. | |

| Firm-B | 11.2% p.a. |

Firm-A can borrow more cheaply than firm-B in both the fixed and floating market. But firm-A wants to ultimately end up borrowing at a floating rate and B at a fixed rate. How might both A and B benefit by using the swaps market? Assume A and B deal directly with each other and split the gains from the swap, 50:50.

Question 7

Companies A and B have been offered the following rates per annum on a $20 million, 5-year loan:

| Fixed rate | Floating rate | |

| Company A | 12.0% | |

| Company B | 13.4% |

Company A wants to end up paying a floating rate while company B desires a fixed rate loan.

Design a swap that will net a bank, acting as intermediary, 0.1% p.a. and appear equally attractive to both companies. Assume the bank pays and receives LIBOR and split any gain in the swap equally between A and B (after the swap dealer has taken a 0.1% p.a. gain).

NOTES

- 1 We use the notation ‘01’, ‘02’ etc., to designate the ‘generic’ year in question (e.g. ‘01’ could be the year 2019).

- 2 In practice, day-count conventions can be a little ‘messy’.

could be different for each reset period (and be different from the day-count convention for the floating leg). However

could be different for each reset period (and be different from the day-count convention for the floating leg). However  is often used for each 6-month period in the pay-fixed leg of the swap, even though the number of days between different reset dates may actually differ from 180 and of course the ‘360’ is arbitrary. But as long as you know the convention being used you can always calculate the fixed dollar cash flows. For example, when calculating fixed cash flows, the swap-market convention in the US is to use the ‘30/360’ convention for either USD or Euro interest rate swaps – hence for our swap, using this US convention:

is often used for each 6-month period in the pay-fixed leg of the swap, even though the number of days between different reset dates may actually differ from 180 and of course the ‘360’ is arbitrary. But as long as you know the convention being used you can always calculate the fixed dollar cash flows. For example, when calculating fixed cash flows, the swap-market convention in the US is to use the ‘30/360’ convention for either USD or Euro interest rate swaps – hence for our swap, using this US convention:  (30/360 × Number of months between repayment dates). So for a 6-month tenor, we have h = 180/360. However, for sterling swaps the fixed leg has a ‘30/365’ day count convention.

(30/360 × Number of months between repayment dates). So for a 6-month tenor, we have h = 180/360. However, for sterling swaps the fixed leg has a ‘30/365’ day count convention. - 3 One practical point to note is that 6-month LIBOR is quoted assuming semi-annual payments with a 360-day year while US T-notes use semi-annual payments but with a 365-day year. Therefore, the LIBOR rate must be multiplied by (365/360) to put it on an equivalent basis to the T-bond rate. Hence, the T-bond equivalent rate (to a LIBOR quoted rate) = LIBOR × (365/360). This need not concern us here.