CHAPTER 4

Futures: Hedging and Speculation

Aims

- To examine how futures can be used for hedging.

- To explain basis risk, cross hedge and rolling hedge.

- To examine some novel types of futures contracts.

- To show how futures are used for speculation.

4.1 HEDGING USING FUTURES

Futures contracts can be used for hedging an existing position in a spot (cash-market) asset. For example, an oil producer might have a large amount of oil coming ‘on stream’ in 3 months' time and may fear a fall in the spot oil price over the next 3 months, so will have to sell their oil at a low spot price. Or, a US exporter who is receiving sterling from the sale of goods in the UK in 3 months, may fear a fall in the spot FX rate for sterling – which implies they will receive fewer dollars when they exchange sterling for dollars.

In the above cases the seller (of oil or sterling) does not know what the spot/cash market price will be in 3 months' time and their future (dollar) receipts are therefore subject to price-risk. Hedging with futures can be used to reduce such risk to a minimum. In practice, using futures contracts cannot reduce price-risk to zero so a ‘perfect hedge’ is usually not possible.

4.1.1 Short Hedge

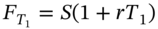

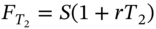

The basic idea behind hedging is very simple. If you are holding (i.e. long) the underlying asset (e.g. stock-ABC) then you need to take a futures position (on stock-ABC) such that the monetary gain, after closing out the futures contract, largely offsets any monetary losses in the spot market, over your chosen hedge period. Futures and spot prices tend to rise and fall together (approximately) dollar-for-dollar because arbitrageurs ensure that ![]() at all times. Hence, on 25 June in order to hedge a long position in stock-ABC with price

at all times. Hence, on 25 June in order to hedge a long position in stock-ABC with price ![]() (over the next 3 months,

(over the next 3 months, ![]() ), you need to short (i.e. sell) September-futures contracts today. If on 25 June the risk-free rate is

), you need to short (i.e. sell) September-futures contracts today. If on 25 June the risk-free rate is ![]() , and the quoted September-futures price is

, and the quoted September-futures price is ![]() .

.

If the spot/cash market price of the stock falls by $10 (on the NYSE) to ![]() over the next 3 months, then arbitrageurs will ensure that the futures price (which matures close to 25 September) will also be close to

over the next 3 months, then arbitrageurs will ensure that the futures price (which matures close to 25 September) will also be close to ![]() . You initially sold the futures contract for

. You initially sold the futures contract for ![]() on 25 June and on 25 September you can ‘buy back’ the futures contract (i.e. close out your futures position) at

on 25 June and on 25 September you can ‘buy back’ the futures contract (i.e. close out your futures position) at ![]() . Your profit is

. Your profit is ![]() – which you obtain from the clearing house in Chicago.

– which you obtain from the clearing house in Chicago.

A ‘sell’ followed by a ‘buy’ for futures contracts (with the same maturity date and underlying asset) means that any delivery to you of the stock is nullified. Closing out means ‘no delivery’ – just the cash settlement of $10.25. Here, the gain on the futures hedge of $10.25 more than offsets the $10 loss on your stocks. Without the hedge you would have lost $10.

A hedge is designed to result in no change in the value of your overall position (i.e. stocks plus futures). You therefore forego the prospect of any overall gains (or losses) when you use futures contracts for hedging.

Let's examine the above hedge in more detail. On 25 June Ms Long holds one stock-ABC with a spot (cash market) price ![]() . Normally Ms Long is willing to accept the price risk of stock-ABC. But suppose over the next 3 months (

. Normally Ms Long is willing to accept the price risk of stock-ABC. But suppose over the next 3 months (![]() year), she thinks the stock market will be more volatile than normal and in particular she fears an exceptionally large fall in stock prices by 25 September, when she might want to sell her stock-ABC or her trading position will be assessed.

year), she thinks the stock market will be more volatile than normal and in particular she fears an exceptionally large fall in stock prices by 25 September, when she might want to sell her stock-ABC or her trading position will be assessed.

To remove any price risk she could sell stock-ABC on 25 June for ![]() and invest the $100 in an interest bearing bank deposit until 25 September, when she could either (a) repurchase the stock-ABC possibly at a lower price (

and invest the $100 in an interest bearing bank deposit until 25 September, when she could either (a) repurchase the stock-ABC possibly at a lower price (![]() ) or at a higher price (

) or at a higher price (![]() ), or (b) continue to hold cash in the deposit account which will have accrued to

), or (b) continue to hold cash in the deposit account which will have accrued to ![]() .

.

There are problems with this strategy. First, if she invests in the bank deposit on 25 June but later, on 25 September, she decides she wants to hold the stock, then she must repurchase stock-ABC at either the low price of ![]() which would be advantageous, or at the high price

which would be advantageous, or at the high price ![]() which would be expensive (relative to the initial price of

which would be expensive (relative to the initial price of ![]() on 25 June). But on 25 June she does not know which of these outcomes might occur, so this strategy has not removed price risk – if she subsequently wants to hold the stock. Also this strategy requires selling stock-ABC on 25 June and repurchasing stock-ABC on 25 September – so she will incur transactions costs in the form of bid–ask spreads and commissions. However, if she is certain she wants to hold cash on 25 September, then investing in the bank deposit guarantees she will have a cash amount of

on 25 June). But on 25 June she does not know which of these outcomes might occur, so this strategy has not removed price risk – if she subsequently wants to hold the stock. Also this strategy requires selling stock-ABC on 25 June and repurchasing stock-ABC on 25 September – so she will incur transactions costs in the form of bid–ask spreads and commissions. However, if she is certain she wants to hold cash on 25 September, then investing in the bank deposit guarantees she will have a cash amount of ![]() in her deposit account on 25 September.

in her deposit account on 25 September.

Instead of using the above strategy, Ms Long can hedge her existing stock position on 25 June by shorting a futures contract. This means that if stock prices rise or fall dramatically between 25 June and 25 September, Ms Long will continue to hold her stocks-ABC (and hence avoid any transactions costs of buying and selling). In addition, with the futures hedge in place she will have neither gained or lost and hence has removed any price risk (unlike the case above). Although hedging with futures allows Ms Long to offset any losses from a fall in stock prices, it does not allow Ms Long to benefit from a rise in stock prices – but this is the outcome that hedging is designed to produce.

The September-futures price on 25 June is ![]() . Can Ms Long who holds stocks-ABC guarantee an outcome of (around) $100.25 on 25 September? Note that on 25 June, the outcome Ms Long seeks to achieve is an effective value for her stocks of

. Can Ms Long who holds stocks-ABC guarantee an outcome of (around) $100.25 on 25 September? Note that on 25 June, the outcome Ms Long seeks to achieve is an effective value for her stocks of ![]() in 3 months' time – she cannot lock in the current stock price

in 3 months' time – she cannot lock in the current stock price ![]() .

.

On 25 June Ms Long initiates the hedge by selling (shorting) the September-futures contract at ![]() (but no money changes hands). Suppose that on 25 September the price of stock-ABC has fallen to

(but no money changes hands). Suppose that on 25 September the price of stock-ABC has fallen to ![]() and the futures to

and the futures to ![]() (Table 4.1).

(Table 4.1).

TABLE 4.1 Hedge (basic data)

| 25 June | 25 September |

|

|

|

|

|

|

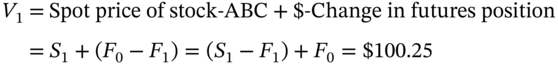

On 25 September Ms Long closes out her futures position by buying (back) the September-futures at the lower price ![]() , making a profit of

, making a profit of ![]() – which approximately offsets the loss in the spot market of $10 (Table 4.2). The value

– which approximately offsets the loss in the spot market of $10 (Table 4.2). The value ![]() (on 25 September) of Ms Long's hedged portfolio is:

(on 25 September) of Ms Long's hedged portfolio is:

TABLE 4.2 Short hedge: outcome on 25 September

| Sale of stocks: |

|

| Gain on futures: |

|

| Total receipts |

|

![]() is known at the outset of the hedge on 25 June but

is known at the outset of the hedge on 25 June but ![]() and

and ![]() are not. Hence the risk in the hedge depends on ‘the basis’ where:

are not. Hence the risk in the hedge depends on ‘the basis’ where:

In our example the value of the hedged portfolio is $100.25 (on 25 September) and this equals the quoted futures price F0 on 25 June – so Ms Long on 25 June has fixed the value of her portfolio, even if the stock price falls. This is a perfect hedge because we made the final basis, ![]() equal to zero – as we assume the futures contract matures on (or near) 25 September so that

equal to zero – as we assume the futures contract matures on (or near) 25 September so that ![]() . In general, if the contract is closed out before the maturity date then b1 will not be zero (but it will be small) – hence there is always some basis risk in a hedge.

. In general, if the contract is closed out before the maturity date then b1 will not be zero (but it will be small) – hence there is always some basis risk in a hedge.

Note that in the hedge, the price that is ‘locked in’ is the futures price ![]() and not the spot price

and not the spot price ![]() . In fact, the spot price at the outset

. In fact, the spot price at the outset ![]() plays no direct role in the calculation of the value of the hedged position on 25 September (see Equation 4.1). The only transactions cost you incur are in selling then buying back the futures and these costs are very small (and usually much lower in the futures market than on the NYSE).

plays no direct role in the calculation of the value of the hedged position on 25 September (see Equation 4.1). The only transactions cost you incur are in selling then buying back the futures and these costs are very small (and usually much lower in the futures market than on the NYSE).

If the futures contract had been on ‘live cattle’ and you require your cattle in Boston it should be obvious that it is better not to pay ![]() on 25 September and take delivery of cattle in the futures contract near Chicago (the delivery point in the futures contract). It is more convenient to take the cash profit on the futures of $10.25, buy your cattle on 25 September in the local market in Boston at the spot price

on 25 September and take delivery of cattle in the futures contract near Chicago (the delivery point in the futures contract). It is more convenient to take the cash profit on the futures of $10.25, buy your cattle on 25 September in the local market in Boston at the spot price ![]() , since then you do not have the additional cost of transporting the cattle between Chicago and Boston. Closing out (just before maturity) rather than delivery (on the maturity date T), also happens with many financial futures contracts (e.g. on stocks, bonds, FX). Also some futures contracts can only be cash settled at maturity rather than taking delivery (e.g. futures on the S&P 500 index, where it would be extremely inconvenient and costly to ‘deliver’ 500 stocks).

, since then you do not have the additional cost of transporting the cattle between Chicago and Boston. Closing out (just before maturity) rather than delivery (on the maturity date T), also happens with many financial futures contracts (e.g. on stocks, bonds, FX). Also some futures contracts can only be cash settled at maturity rather than taking delivery (e.g. futures on the S&P 500 index, where it would be extremely inconvenient and costly to ‘deliver’ 500 stocks).

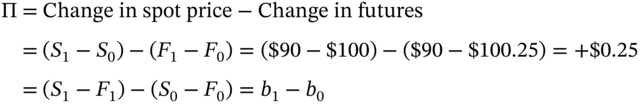

An alternative way of representing the hedge is to examine the net profit![]() , that is, the loss (gain) on the spot position relative to the gain (loss) on the short futures position.

, that is, the loss (gain) on the spot position relative to the gain (loss) on the short futures position.

In this example, the gain on the futures position is $10.25 which more than offsets the loss on the spot position of $10 and hence the hedge is broadly successful. The profit from the hedged position depends on the change in the basis. The change in the basis is small because spot and futures prices are highly correlated. Thus the hedge position is much less risky than the unhedged position – since without the hedge the loss (or gain) would be the much larger amount ![]() . Note also that the ‘initial basis’ b0 is known and ‘fixed’ at the outset of the hedge. It is the ‘final basis’

. Note also that the ‘initial basis’ b0 is known and ‘fixed’ at the outset of the hedge. It is the ‘final basis’ ![]() that is the source of uncertainty in the net profit.

that is the source of uncertainty in the net profit.

4.1.2 Long Hedge

Suppose on 25 June, the portfolio manager of a pension fund, Ms Wait, knows she will receive a cash inflow in 3 months' time on 25 September (from contributors to the pension fund), which she will use to purchase stocks. The stock price on 25 June is ![]() – but she knows she cannot lock in this price by hedging – she can only lock in today's quoted futures price.

– but she knows she cannot lock in this price by hedging – she can only lock in today's quoted futures price.

She is worried that stock prices will rise – so her stocks will cost more in 3 months, when the cash arrives to purchase them. To hedge, Ms Wait goes long (i.e. buys) a futures contract on 25 June at ![]() and takes delivery of the stocks in 3 months and pays $100.25 per stock (in Chicago) on 25 September. Alternatively, Ms Wait could simply close out her position by selling the futures contract on 25 September (see Table 4.3).

and takes delivery of the stocks in 3 months and pays $100.25 per stock (in Chicago) on 25 September. Alternatively, Ms Wait could simply close out her position by selling the futures contract on 25 September (see Table 4.3).

TABLE 4.3 Long hedge: outcome on 25 September

| Sale of stocks: |

|

| Loss on futures: |

|

| Total receipts |

|

Suppose we have the same outcome as before, namely the stock prices falls to ![]() , as does the futures price

, as does the futures price ![]() . The cost of buying the stocks in the cash market (on the NYSE) is

. The cost of buying the stocks in the cash market (on the NYSE) is ![]() , but the cash loss from the long futures is

, but the cash loss from the long futures is ![]() , making a net cost of buying the stocks on 25 September = $90 + $10.25 = $100.25. Hence, the hedge when cash settled also ‘locks in’ the futures price

, making a net cost of buying the stocks on 25 September = $90 + $10.25 = $100.25. Hence, the hedge when cash settled also ‘locks in’ the futures price ![]() . Again, this is because we have assumed the final basis

. Again, this is because we have assumed the final basis ![]() is zero.

is zero.

Some might find it confusing that the hedge does not ‘lock in’ a price of ![]() on 25 September. But this is impossible since the price

on 25 September. But this is impossible since the price ![]() on the NYSE applies to 25 June – you can only ‘lock in’ the futures price

on the NYSE applies to 25 June – you can only ‘lock in’ the futures price ![]() (quoted on 25 June for maturity on 25 September).

(quoted on 25 June for maturity on 25 September).

Note that with hindsight, it would have been better if the hedge had not been undertaken, since then the cost of buying the stocks on 25 September would have been ![]() . However, when the hedge was initiated in June, the hedger could not have known that the price would fall over the next 3 months – hindsight is a wonderful thing.

. However, when the hedge was initiated in June, the hedger could not have known that the price would fall over the next 3 months – hindsight is a wonderful thing.

In the above examples we assume (for expositional clarity) that on 25 September, ![]() . In practice this equality only holds exactly on the delivery/maturity date of the futures contract which might be a few days later at T = 28 September (say). If

. In practice this equality only holds exactly on the delivery/maturity date of the futures contract which might be a few days later at T = 28 September (say). If ![]() on 25 September then

on 25 September then ![]() might actually be equal to $90.1 (say) rather than

might actually be equal to $90.1 (say) rather than ![]() assumed above. Hence the final basis would be

assumed above. Hence the final basis would be ![]() , so the above numerical results would be slightly different but the general points made are still valid.

, so the above numerical results would be slightly different but the general points made are still valid.

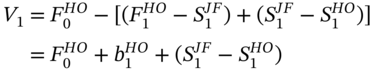

4.1.3 Cross Hedge

If the asset underlying the futures contract is not the same as the asset held by the hedger then there is an additional source of basis risk. Let ![]() be the cash market price of heating oil and

be the cash market price of heating oil and ![]() the price of a heating oil futures contract.

the price of a heating oil futures contract.

On 25 June, Cloud-9, an airline, knows that it is going to purchase jet fuel in 2 months' time on 25 August, at its hub airport (LAX) at the cash market price ![]() . But it fears a rise in jet fuel prices. Suppose there is no futures contract available on jet fuel1 so Cloud-9 hedges by going long September-heating oil futures contracts (with a maturity date on 28 September). The effective cost

. But it fears a rise in jet fuel prices. Suppose there is no futures contract available on jet fuel1 so Cloud-9 hedges by going long September-heating oil futures contracts (with a maturity date on 28 September). The effective cost ![]() of the jet fuel for Cloud-9 on 25 August (when the airline closes out its heating oil futures contracts) is:

of the jet fuel for Cloud-9 on 25 August (when the airline closes out its heating oil futures contracts) is:

which can be written:

so there is an additional source of basis risk arising from the difference between the spot prices of jet fuel and heating oil on 25 August. Also since ![]() equals zero only on the maturity date of the futures (28 September), the choice of the futures delivery month is important.

equals zero only on the maturity date of the futures (28 September), the choice of the futures delivery month is important.

Clearly if you are going to close out your futures position on 25 August, then on 25 June you must choose a futures contract that matures after 25 August. Also, the size of the final basis ![]() is more uncertain, the longer the gap between the end of the hedge period (

is more uncertain, the longer the gap between the end of the hedge period (![]() = 25 August) and the maturity of the futures contract (here T = 28 September). It is therefore best to choose a delivery month that is just after the hedge period – as this futures contract is likely to be heavily traded, with high liquidity and low transactions costs.

= 25 August) and the maturity of the futures contract (here T = 28 September). It is therefore best to choose a delivery month that is just after the hedge period – as this futures contract is likely to be heavily traded, with high liquidity and low transactions costs.

For example, suppose on 25 June when Cloud-9 initiates its hedge, heating oil futures contracts are available with maturity dates on 27 June, 28 September, 29 December and (next year on) 25 March. If you intend to close out the hedge on 25 August then you should probably use the September contract – this will ensure the final basis is reasonably small (i.e. ![]() ) and the hedge will work reasonably well.

) and the hedge will work reasonably well.

4.1.4 Rolling Hedge

Assume it is now 5 April 2019 and Ms Refiner is holding 10,000 barrels of oil (i.e. she is long the underlying) which she will sell on 5 January 2020. She fears a price fall, so to hedge she needs to sell (short) oil futures, today. The contract size for oil futures is for delivery of 1,000 barrels, so to hedge her cash-market position of 10,000 barrels she needs to sell (short) ten futures contracts. Futures contracts are available with maturity dates on the 28th of the month for June-2019, September-2019, December-2019 and March-2020. However, on 5 April she feels that only the ‘nearby’ June-2019 contract is liquid enough (with low transactions costs) to use in the hedge.

One possible scenario is that on 5 April 2019 she shorts ten June-2019 futures contracts. Towards the end of June she buys back the ten June-2019 contracts which are about to expire and she simultaneously shorts ten September-2019 contracts (which are now the ‘nearby contract’). Towards the end of September-2019 she closes out (buys back) these ten September-2019 contracts and then shorts ten December-2019 futures contracts. Finally, at the end of December-2019 she closes out (buys back) these ten December-2019 contracts – leaving her unhedged for a short period until 5 January 2020.

Every 3 months, she hedges using the ‘next nearby contract’. This is a rolling hedge as she periodically ‘rolls over’ into the next nearby contract. Spot and futures prices move approximately dollar-for-dollar. So, for example, if the spot price of oil falls continuously over the coming year, she receives less from selling her barrels of oil, but this is offset by cash receipts (![]() ) when she closes out the ten short futures contracts by buying them back at a lower price, when each contract matures. She therefore executes a rolling hedge, over each 3-month period, always using the next nearby (liquid) contract.

) when she closes out the ten short futures contracts by buying them back at a lower price, when each contract matures. She therefore executes a rolling hedge, over each 3-month period, always using the next nearby (liquid) contract.

An example of a rolling hedge with energy futures undertaken by the German firm Metallgesellschaft can be found in Finance Blog 4.1 – it illustrates some of the practical difficulties of trying to maintain a hedge by rolling over short-dated futures contracts.

4.1.5 Rules for Hedging

- If you are long the cash-market asset (e.g. stocks) and hence fear a price fall, then hedge by taking a short futures position today (i.e. sell futures contracts).

- If you are planning to purchase the asset in the future (i.e. you are short in the cash market) and hence fear a price rise, then hedge by going long today (i.e. buy a futures contract).

- Choose a futures contract which is written on the spot (cash-market) asset in question. This maximises the correlation between F and S. Otherwise use a cross-hedge where there is a high correlation between the cash market asset you are trying to hedge (e.g. jet fuel) and the futures contract used in the hedge (e.g. heating oil futures).

- For hedging over a relatively short period of time, choose a futures contract with an expiration date just longer than the hedge period. This minimises basis risk since you close out just before the maturity date (T) of the futures, so

.

. - Suppose the hedge is for a long period and futures contracts with long maturity dates are either not available or illiquid with high transactions costs (bid–ask spreads, etc.). Then choose liquid, short-dated futures contracts (i.e. the next nearby contract) and ‘roll over’ the hedge as each ‘short-dated’ futures contract approaches its maturity date.

- Losses on the futures position may involve payments of ‘variation margin’ and therefore a hedger must have lines of credit or other assets available to meet these margin calls.

- You need to choose the appropriate number of futures contracts to use in the hedge – this is discussed in Chapter 5.

4.2 NOVEL FUTURES CONTRACTS

This book is primarily concerned with hedging positions in financial assets (and to a lesser extent in tradable commodities such as oil and gas) but it is worthwhile reflecting on the possibility of hedging more general risks that society faces. For example, almost all major countries such as the USA, UK, Japan, Australia, Brazil, and Asia have experienced booms and slumps in the housing and commercial property markets. If you have recently purchased a house only to find that its value has plummeted, this can be devastating. Conversely, if first-time buyers fail to buy before a major housing boom, they can be excluded from homeownership for a long time (and maybe forever). Take another even more powerful example. Individuals cannot adequately insure against major changes in their real incomes – through no fault of their own (e.g. booms and slumps either nationally or regionally and in particular industries). There seems to be no adequate mechanism for individuals to insure against these social risks. Could derivatives markets be used to provide such insurance and hence ‘spread’ these risks across a wide number of participants – just like when we use futures contracts to hedge changes in commodity and stock prices?

Robert Shiller of Yale University, who won the Nobel Prize in economics in 2013 (along with Eugene Fama), favours the establishment of futures markets based on house (and other real estate) price indices and on ‘perpetual claims’ on income. These contracts could be used to hedge the price risk involved in owning a home and the risk of unforeseen changes in income (e.g. your own occupational income or the real income (GDP) of the whole domestic economy). Shiller (1993) provides a provocative analysis of these issues, some of which are outlined in Finance Blog 4.2.

Shiller also considered the risks to individuals from changing household incomes as relative earnings change over long periods of time (for example, incomes in the industrial sector may fall relative to those in the information technology [IT] sector over a 10-year period).

Hedging using futures contracts based on an underlying index of national, regional or occupational incomes, works in much the same way as for house prices. (But note that Shiller's actual proposal is more subtle being based on ‘long-run’ or perpetual income, rather than current or next year's income). If your ‘own-income’ is positively correlated with regional income, then you (or more likely a financial institution who sold you an ‘income insurance policy’) would hedge by shorting ‘regional income futures’ contracts. If your income fell and along with it regional income, then you would receive margin payments (from the futures clearing house). These margin receipts could then be reinvested in a portfolio of income claims in a wide variety of other countries, which would have less variability than your own income stream – hence reducing your overall income risk. The problem of a futures-hedger meeting margin payments remains a problem and requires banks to lend against future income – for the purpose of covering these margin payments.

There are many other practical and provocative ideas in Shiller's books Macro Markets (1994) and Finance and the Good Society (2013). Who knows, in the future, your children may use these types of futures contract to hedge some of their key long-term ‘lifetime risks’.

4.3 SPECULATION

Speculation with futures is relatively straightforward. Consider speculation using a futures contract on stock-ABC. (We deal with speculation using ‘stock index futures contracts’ in Chapter 5.) You are using futures contracts to gamble on forecasts for the price of stock-ABC.

If you think the price of stock-ABC will rise (fall) in the future (on the NYSE) then today you will speculate by buying (selling) a futures contract (on stock-ABC) at ![]() in Chicago. If you forecast the direction of change in stock prices and hence future prices, then you will be able to close out your futures position at a profit – if you forecast incorrectly you will close out your futures position at a loss. Speculation is risky.

in Chicago. If you forecast the direction of change in stock prices and hence future prices, then you will be able to close out your futures position at a profit – if you forecast incorrectly you will close out your futures position at a loss. Speculation is risky.

If you close out a long futures position before maturity then the profit/loss on each futures contract is ![]() (i.e.

(i.e. ![]() if

if ![]() and

and ![]() if

if ![]() ). On the maturity date (T) of the futures, the stock price and futures price must be equal (because of arbitrage)

). On the maturity date (T) of the futures, the stock price and futures price must be equal (because of arbitrage) ![]() . Hence, if a speculator holds the long futures contact to maturity (=T), she can pay

. Hence, if a speculator holds the long futures contact to maturity (=T), she can pay ![]() , at T, take delivery of the stock (in Chicago) and immediately sell it on the NYSE for

, at T, take delivery of the stock (in Chicago) and immediately sell it on the NYSE for ![]() . Hence her speculative profit at T on her long futures position at maturity is

. Hence her speculative profit at T on her long futures position at maturity is ![]() (which can be either positive or negative).

(which can be either positive or negative).

Similar arguments to the above apply if a speculator initially sells a futures contract, because she thinks the stock price and hence the futures price will fall, on or before the maturity date of the futures contract.

4.3.1 Speculation with Stocks Versus Futures Contracts

What are the institutional differences between speculating on changes in the price of stock-ABC on the NYSE and speculating with futures (on stock-ABC) in Chicago. If you speculate by buying stock-ABC on the NYSE you (may) have to use your ‘own funds’ to buy the stock and pay any transactions costs (bid–ask spreads and brokers' commissions). If you use futures contracts on the stock, the long futures position provides leverage, since you do not have to use any ‘own funds’ when you initiate the futures position (and transactions costs in futures markets are generally much lower than those on the NYSE).

When using futures you have to place a relatively small ‘good faith deposit’ in your margin account. Of course, if you are long (short) the futures and the futures price falls (rises) then you may have to ‘top up’ your margin account and speculators therefore need ready cash or collateral (e.g. T-bills) available.

For a speculator holding stock-ABC to benefit from a forecast rise in stock prices, she can (in principle) wait indefinitely for the price to rise. In contrast, when taking a speculative long position in a futures contract, the stock price must rise before the maturity date in the futures contract. There is a ‘time limit’ when using a long futures position for speculation.

When using stocks to bet on a fall in stock prices a speculator has to short-sell stocks. However, if she cannot ‘borrow’ the stock from her brokers for a long enough time period she may not be able to ‘hold’ her short position long enough to benefit from the predicted fall in stock prices. Similarly, when using a short futures position to gain from a fall in stock (and futures) prices, the stock price must fall before the maturity date in the futures contract. In practice there is a ‘time limit’, either when short-selling a stock or when speculating using a short futures position – the former time limit is somewhat uncertain (depending on your relationship with your broker) and for the futures, the time limit is fixed by the maturity of the contract.

Speculators take an ‘open’ or ‘naked’ position and hence the transaction is risky. There are three broad types of speculator: scalpers/algorithmic traders, day traders and position traders.

- Scalpers (Algorithmic traders, High Frequency Traders, HFT) transact (mainly) on electronic platforms and may close out their positions within milli-seconds or at most minutes. Traders who use graphs of tick-by-tick prices to predict changes in futures prices come under the generic term ‘chartists’ of ‘technical analysis’. Algorithmic traders buy and sell based on complex mathematical formulas often based on very short-term price movements and volume/turnover in the market often helps predict future short-term price movements.

- Day Traders usually close out their positions within a few hours, or at most within the trading day. They often trade, based on their views about ‘news items’ (e.g. future company dividend outcomes, forecasts of changes in interest rates or FX rates) that may affect futures prices.

- Position Traders may hold their positions for as little as one day to one month, or more. An outright open (naked) position in futures is extremely risky so ‘position traders’ often engage in spread trading.

- Spread trading involves long-short trades in two different futures contracts, so that there is a negative correlation between the two futures positions and this reduces the risk exposure. The margin requirements for spread trades are usually less than for open/naked positions. The two main types of spread trading in futures markets are:

- Intracommodity spread: a long and short position in two futures contracts on the same underlying asset – but with different maturity dates.

- Intercommodity spread: a long and short position in two different futures contracts (e.g. on Microsoft and Apple stocks) – but with the same maturity date.

- Spread trading involves long-short trades in two different futures contracts, so that there is a negative correlation between the two futures positions and this reduces the risk exposure. The margin requirements for spread trades are usually less than for open/naked positions. The two main types of spread trading in futures markets are:

An intracommodity spread relies on the fact that futures prices on long maturity dated contracts, move more than futures prices on nearby contracts, when there is a change in the underlying asset price.2 For example, if on 25 January you think a large rise in oil prices is likely over the next month, you would take a long position in a long-maturity oil-futures contract (e.g. the December-futures) and a short position in a short-maturity contract (e.g. the March-futures). Even if the spread trader forecasts incorrectly and it turns out that prices of oil fall, the large loss on the long-futures is partly offset by the gain on the short position.

An example, of an intercommodity spread is when a US investor takes a long position on 25 January in a sterling futures contract (with December maturity date) and a short position in yen futures (also with a December maturity date). The speculator is gambling on a sterling appreciation (against the US dollar) which exceeds that for the yen (against the US dollar) then the spread trader after closing out both contracts will make an overall profit. If the US investor's forecast is incorrect, some (or all) of the losses on the long sterling contract may be offset by the gains on the short yen contract.

4.4 SUMMARY

- If an investor is long the underlying cash-market asset (e.g. holds stocks, gold, oil, wheat, etc.) then to hedge, they should sell (short) futures contracts today (and vice versa), and close out the futures contracts at the end of the hedge period. Any change in price of the spot asset should be largely offset by the profit/loss on the futures position.

- There is always some basis risk in a hedge – the futures and spot prices may not move exactly dollar-for-dollar because of changes in interest rates, the yield on the underlying asset (e.g. dividend yield), storage costs and the convenience yield (for commodity futures).

- The maturity of the futures contract used in the hedge is usually greater than the maximum horizon over which you want to hedge (e.g. 3 months, 1 year) but this will also depend on liquidity and transactions costs associated with the specific futures contract chosen.

- The most conventional hedge is to use a futures contract that matures just after the end of the chosen hedge period. However, when hedging over a long period, long-dated futures may be illiquid and then short-dated (nearby) futures contracts can be used and ‘rolled over’ into the next short dated contract – this strategy has ‘roll-over risk’ and more basis risk than a conventional hedge.

- Speculation with futures allows almost unlimited leverage (since any margin payments you have to provide are small and usually earn interest). Hence the proportionate gain (on any own-funds used) is higher for speculation with futures, than speculation by purchasing the underlying cash-market asset using your ‘own funds’.

EXERCISES

Question 1

Explain how a futures contract on a stock-X can be used for hedging your current holdings in stock-X.

Question 2

What is basis risk in a hedge and is it ever zero?

Question 3

Why might you need to ‘roll over the hedge’ when using futures contracts?

Question 4

Why would an oil consumer (Haulage Plc) use a ‘futures hedge’ to remove ‘price risk’ on its future purchases of oil in the cash market?

Question 5

You hold a stock worth S0. Does a ‘perfect hedge’ using futures, involve locking in the current spot price, so the value of your portfolio in the future will equal its current value? Consider closing out the futures either before maturity or at maturity.

Question 6

Discuss the basic idea behind Shiller's approach to hedging house price changes by using ‘novel’ future contracts.

Question 7

Suppose you hedge a long position in stocks (currently worth ![]() ), using futures contracts (with current price

), using futures contracts (with current price ![]() ). Do you ‘lock in’ a known value for your portfolio in the future? Alternatively, are any losses/gains in the value of your stocks exactly compensated by gains/losses, when you close out your futures contracts? Assume you close-out your futures contracts just before maturity at

). Do you ‘lock in’ a known value for your portfolio in the future? Alternatively, are any losses/gains in the value of your stocks exactly compensated by gains/losses, when you close out your futures contracts? Assume you close-out your futures contracts just before maturity at ![]() (and your stocks are worth

(and your stocks are worth ![]() ). Explain.

). Explain.

NOTES

- 1 Until recently there was not a futures contract on jet fuel. But airlines tend to hedge using heating oil futures because these contracts are more liquid (in the financial meaning of the word!) than the more recently introduced, futures on jet fuel.

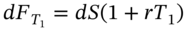

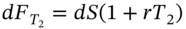

- 2 Simplifying a little this can be seen by noting that

and

and  so that

so that  and

and  and hence the longer the time to maturity

and hence the longer the time to maturity  the greater the change in the futures price. (For simplicity we have assumed the yield curve is flat and changes in S occur over a small time interval.)

the greater the change in the futures price. (For simplicity we have assumed the yield curve is flat and changes in S occur over a small time interval.)