CHAPTER 43

Securitisation, ABSs and CDOs

Aims

- To analyse the process of securitisation.

- To show how structured products such as asset backed securities (ABSs), collateralised debt obligations (CDOs) and ABS-CDOs give rise to credit enhancement.

- To outline the importance of ABS-CDOs in the 2008–9 credit crisis.

- To examine single tranche trading, synthetic CDOs, and total return swaps.

Banks can reduce the credit risk on their ‘banking book’ by securitisation. They ‘bundle up’ a portfolio of loans and sell securities which entitle the investor (e.g. a hedge fund or pension fund) to the promised future cash flows from these loans – so the credit risk is transferred from banks to the holders of the securitised assets. Often the cash flows from securitised assets are paid out in order of priority, known as tranches or a waterfall. Senior tranches get paid first and are the least risky and the equity tranche gets paid last and is the most risky. These securitised assets are known as asset backed securities (ABSs) and collateralised debt obligations (CDOs). They are multi-name credit derivatives since the loans in the securitised assets originate from many different companies (or individuals in the case of home mortgages or car loans). In this chapter we discuss how ABSs and ABS-CDOs are constructed, how they provide ‘credit enhancement’, and the risks posed by these securities particularly in the 2008–9 credit crunch.

43.1 ABS AND ABS-CDO

Securitisation is the term used when issuing marketable securities backed by cash flows from ‘assets’ which are often illiquid (e.g. bank loans). It became a very large market in the 2000–7 period, then faltered after the 2008–9 credit crunch but has substantially recovered in recent years.

ABSs depend on future promised cash flows from corporate loans by banks, aircraft leases, car loans (e.g. VW, General Motors), credit card receivables (most large banks), music royalties from a back catalogue (e.g. David Bowie's estate and Rod Stewart), telephone call charges (e.g. Telemex in Mexico) and football season tickets (e.g. Lazio, Real Madrid). If the underlying assets in the securitisation are cash flows from bonds issued by corporates or countries (i.e. fixed-income securities) then the ABS is referred to as a collateralised debt obligation (CDO).

43.1.1 Special Purpose Vehicles

For example, suppose that MegaBank has made a series of long-term corporate loans and has therefore taken on large credit exposures. One way of reducing this exposure is for MegaBank to create a separate legal entity known as a special purpose vehicle (SPV) (or special investment vehicle, SIV), into which the loans are ‘sold’ – therefore they become ‘off balance sheet’ for the bank. If MegaBank gets into financial difficulties with its other activities (e.g. losses due to a rogue trader), the loans in the SPV cannot in principle be claimed by MegaBank's creditors. Similarly, if the loans in the SPV become insolvent, MegaBank's normal activities are (in principle) protected from these losses.

Often the SPV finances its initial loan purchases by issuing asset backed commercial paper (ABCP) to investors, with maturities between 1 and 12 months. The SPV is therefore initially financing its purchases of long-maturity assets (e.g. bank loans) using short-term ABCP. If there are no loan defaults, the SPV makes a profit on the positive long-short spread, over the period that it holds the loans. The aim of the SPV is to sell asset backed securities to ‘final investors’ (e.g. pension funds, insurance companies, private wealth funds, sovereign wealth funds or wealthy individuals), which then entitles these investors to the stream of promised future payments from the corporate loans.

After securitisation the default (credit) risk on the loans is spread across many investors, rather than just being held by MegaBank (or the SPV). MegaBank continues to collect the interest and repayments of principal on the loans (for a fee) but passes these cash flows to the owners of the ABS (e.g. pension funds) – hence the term pass-through securities.

For example, if the underlying assets are home loans to individuals, the ABS is referred to as a residential mortgage backed security (RMBS). In the US, the Government National Mortgage Association (GNMA or ‘Ginnie Mae’) bundles up home mortgages into relatively homogeneous ‘pools’ – for example, $100m of 6%, 20-year conventional mortgages. GNMA then issues, say, 10,000 RMBSs, so each purchaser of a RMBS has a claim to $10,000 of these mortgages and is entitled to receive 1/10,000 of all the payments of interest and principal. RMBSs are marketable and highly liquid. From an investor's point of view, purchasing such securities provides them with a higher yield than on T-bonds and allows them to take on exposure to mortgage loans. But they can at any time sell the RMBS in the secondary market to other investors (at whatever the current market price happens to be).

Investors in ABSs take on the default risk which arises if the underlying borrowers default on their payments. If you hold a diversified portfolio of ABSs then the overall default risk depends on the correlations between default risks for the different categories of asset backed securities (e.g. do most people who have credit card debt tend to default at the same time as (other) people, who owe money on car loans, home mortgages etc.?).

43.1.2 Tranches and a Waterfall

In the above example of a RMBS each investor has equal risk. Usually an ABS is structured so investors can decide whether they are willing to take ‘the first hit’ either from any defaults or from non-payment of interest – or, if they are rather more risk-averse, they can choose to be last to ‘take the hit’, if cash flows from the underlying assets are less than expected.

ABSs (or ‘cash-CDOs’) are a way of ‘repackaging’ credit risk to create ‘tranches’ of debt which have different seniority of payment and hence different risk characteristics. In this way, debt of average risk can be split into bundles of ‘high’ to ‘low’ risk and hence are structured to suit the risk appetite of different investor groups. For example, hedge funds may be willing to hold the ‘high risk’ part of an ABS but pension funds may only be willing to hold ‘low risk’ assets in the ABS.

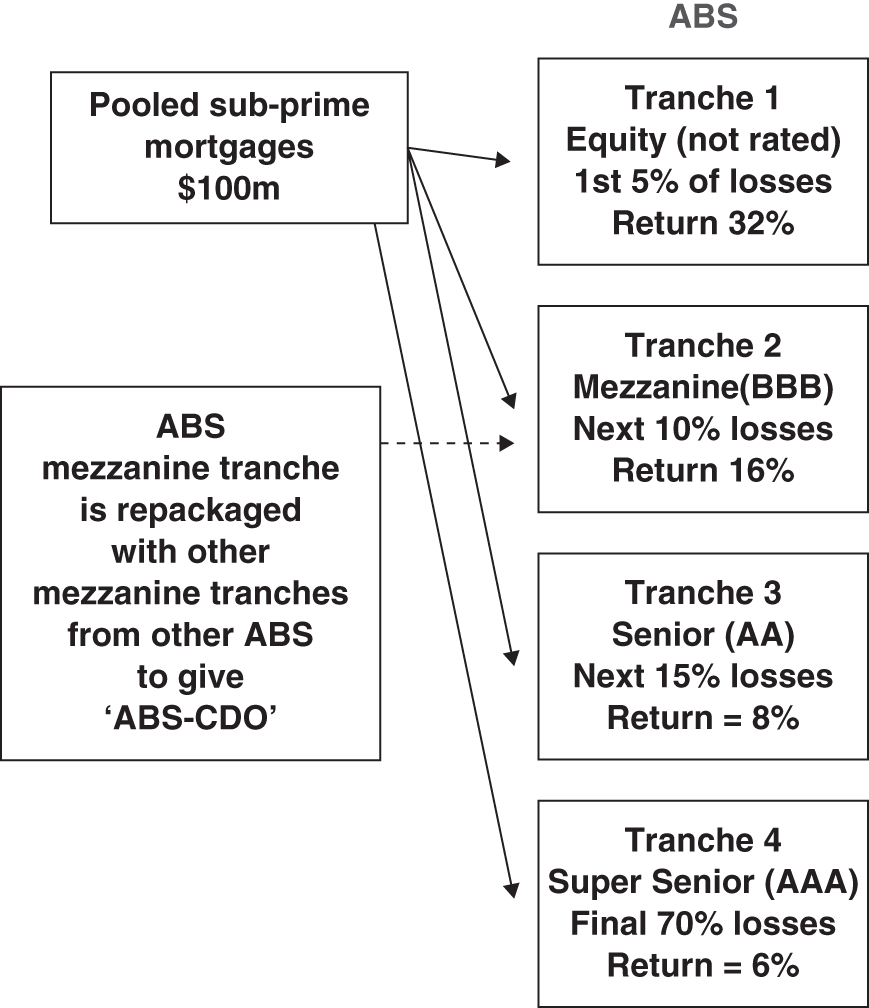

A pool of bank loans (or corporate bonds), each with different default risks are placed in a portfolio, where the assets have an average promised yield of 8.5% (say). This portfolio of assets is sold by the originator (e.g. MegaBank) to an SPV. The loans might then be classified as prime, non-prime, or sub-prime by the SPV. Any one of these three ‘classifications’ (e.g. sub-prime loans) might themselves then be split into four further tranches (Figure 43.1).

FIGURE 43.1 ABS

The ‘equity tranche’ (of the underlying sub-prime loans) are then designated as having to take the first 5% of any losses due to a credit event (e.g. defaults) – this is a very risky tranche since if only 2.5% of the sub-prime loan portfolio defaults, this amounts to a 50% loss on the first tranche.1 The equity tranche is often retained by the originator of the ABS (e.g. MegaBank) since it is difficult to sell to investors, but sometimes this tranche may be purchased by a hedge fund (possibly financed by a loan from MegaBank!).

The second, mezzanine tranche might be liable for the next 10% of losses, followed by the senior tranche which covers the next 15% of losses, leaving the fourth (super-senior) tranche liable for any losses greater than 30%, on the initial portfolio of loans. Tranches 2–4 of the ABS are sold to investors.

Representative promised yields on tranches 4 (least risky) to 1 (most risky) might be 6%, 8%, 16%, and 32% p.a. Cash flows from the underlying assets are first paid to tranche-4 (super-senior) until a return of 6% is obtained (on the principal in the tranche) and any remaining cash flows then go to tranche-3 until it secures its promised return of 8% and so on. So payments from the ABS are structured to be paid out in a known order of seniority (known as a waterfall).

Tranche-4 might be rated AAA by the rating agencies (e.g. Standard & Poor's, Moody's or Fitch) since it will not be affected by credit events until the original portfolio has fallen in value by more than 30%. The ratings for the other tranches will depend on their perceived risk, which depends on the default risk for each bond in that tranche and the default correlations between the original issuers of these bonds/loans.

Hence ABSs are a means of creating some ‘high quality’ debt from ‘average quality’ debt, in the original portfolio of bonds/loans – as long as each tranche of the debt is correctly rated and gives the correct ‘signals’ to buyers of the ABS about their true risk exposure. Also, the originator of an ABS (an SPV) can trade the bonds held in the ABS portfolio providing (for example) that the agreed degree of diversification in the underlying bond portfolio is maintained.

The originator of the ABS sells the tranches to ‘final investors’ for more than they paid for the underlying bonds and also pass on the credit risk to investors. As defaults begin to rise, tranche-1 (the equity tranche) will fail to achieve its promised rate of return and if defaults continue these investors may not get all of their principal repaid. A very high level of defaults may result in the more senior tranches being affected.

43.1.3 Interest and Principal Repayments

All loan repayments can be split into a repayment of interest and principal. Cash flows are allocated to tranches via the waterfall and there is usually a separate waterfall for the interest and principal cash flows. On any payment date, any excess payment over the ‘interest due’ will constitute a repayment of the outstanding principal. Interest payments are allocated to the super-senior tranche first, until the super-senior tranche earns its promised return (on its outstanding principal amount). Next in line for interest payments is the senior tranche etc., until finally, if total interest payments are sufficient, the equity tranche is last to be paid.

Repayments of principal follow a similar pattern and first to be paid is the super-senior tranche and finally down to the equity tranche. If there are defaults on any principal repayments then the equity tranche takes the first 5% of losses and its outstanding principal is reduced accordingly. If losses are greater than 5% the equity tranche loses all of its designated principal amount and the mezzanine tranche takes the next 10% of losses of principal repayments etc. Hence cash flows go first to the super-senior tranche and last to the equity tranche and any losses of principal (defaults) are borne first by the equity tranche and last by the super senior tranche.

43.1.4 Rating Agencies

The ABS is structured so the super-senior tranche is rated AAA with the mezzanine tranche usually rated BBB and the equity tranche is unrated. The creator of the ABS will ‘negotiate’ with the rating agencies to determine what is required to obtain a AAA-rating. The ABS originator tries to make the super-senior tranche (of loans/corporate bonds) as large as possible, subject to it obtaining a AAA-rating from one of the rating agencies. This is because there is a large market for AAA-rated securities, partly because of regulatory requirements which require certain financial institutions to hold a minimum proportion of AAA-assets (e.g. pension funds, insurance companies). The SPV which creates the ABS makes a profit because the value-weighted average return on the underlying assets (e.g. loans and bonds), exceeds the weighted average return offered to all investors who hold the ABS tranches.

The mezzanine tranches of ABSs are often difficult to sell to investors. Clearly the risk depends in part on the characteristics of the underlying borrowers and on the macroeconomic environment. For example, in most cases, the only information for investors who purchased ABSs based on home loans was the borrowers' loan-to-value ratios and their FICO (Fair Isaac Corporation) scores (which represent the credit worthiness of the borrower and range from 300 to 850). But there is an incentive for property valuation assessors to put an artificially high value on a property so it then has a low loan-to-value ratio, which might increase repeat business from mortgage brokers. Also, some FICO scores were of doubtful quality given that a mortgage broker has an incentive to ‘sell’ mortgages to earn commissions. These conflicts of interest are known as ‘agency problems’ – the incentives of the two parties to the contract are not aligned. There may also be ‘asymmetric information’ if the mortgage broker has superior information to the borrower and does not disclose all relevant information – e.g. does not adequately explain that the interest charged may rise in future years, after an initial low ‘teaser rate’.

43.1.5 ABS-CDO (Mezz-CDO, CDO-squared)

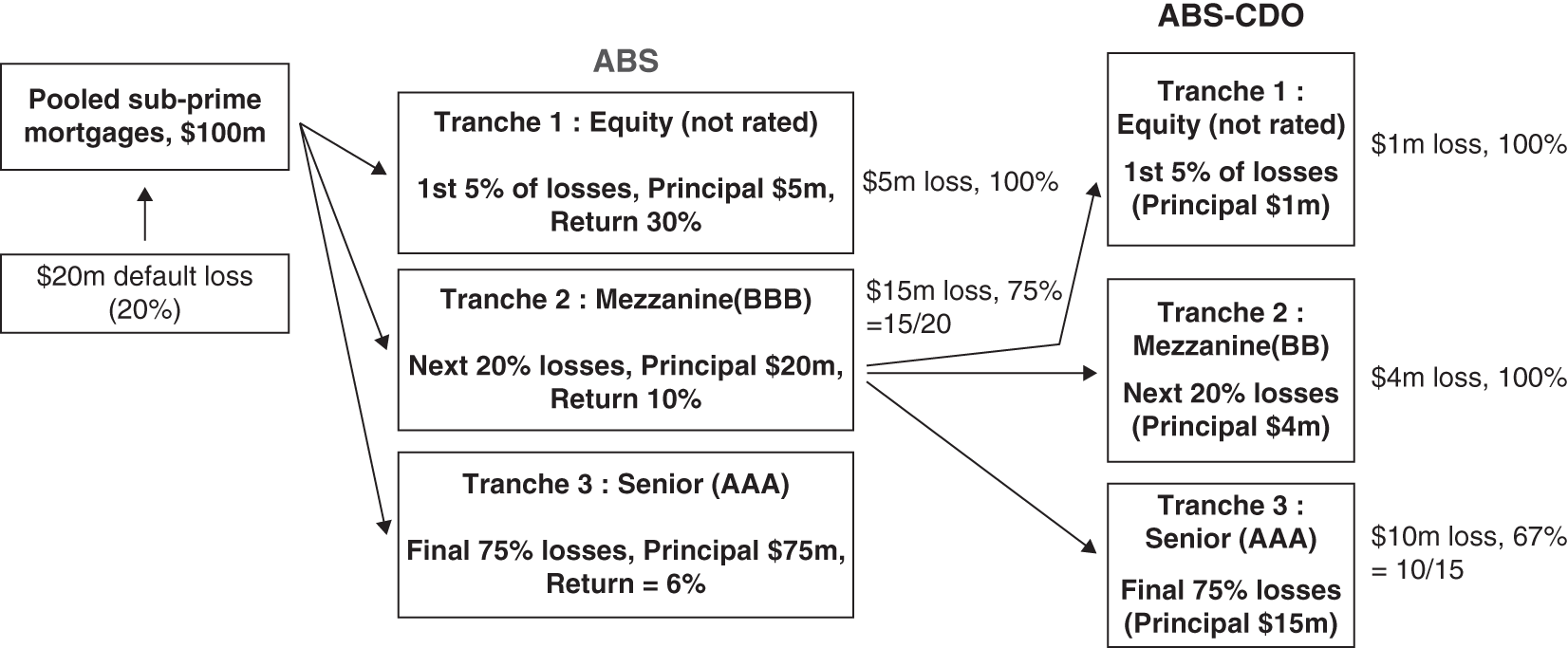

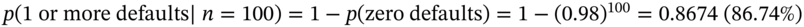

The risk in the mezzanine tranches of an ABS can be overcome to some extent by taking the mezzanine tranches from, say, 20 different ABSs (e.g. on mortgages, car loans, credit card receivables etc.) and bundling them up into say, three further tranches (Figure 43.2) – this is an ABS-CDO (or Mezz-CDO or CDO-squared).

FIGURE 43.2 Leveraged losses

In an ABS-CDO, the equity tranche might take the first 5% of losses, the mezzanine tranche the next 20 per cent and the senior tranche the final 75 per cent of losses. The senior tranche might be given a AAA-rating and the mezzanine tranche a BBB-rating. Once again, payments are structured to be paid out in a known order of seniority (the waterfall) and may result in the creation of highly rated debt from a debt-pool that had an initial overall low credit rating – this is credit enhancement. The difficulty from the investor's point of view is in assessing the true underlying risk of the rather complex tranches in an ABS-CDO – this was part of the cause of the sub-prime mortgage crisis in the USA which began in 2007–8.

43.2 CREDIT ENHANCEMENT

Credit enhancement is achieved by using the waterfall to place the underlying assets (e.g. bonds/loans) into several tranches where the senior tranche is structured to have a lower default risk (and hence higher credit rating) than the original loans/bonds themselves. To see how this works consider the simple case of two BBB-rated bonds on different companies (X and Y), each with a face value of $1. To simplify, assume the probability of default for X and Y are independent of each other (i.e. if X defaults in a particular year, this has no influence whether Y defaults).

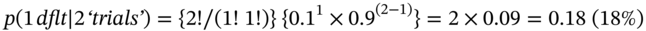

Suppose the probability of default for each bond is ![]() (in any year) and the correlation between defaults is zero (i.e. credit risks are independent). We now create two tranches, each containing $1 notional. The junior tranche does not pay out if (a) either one of the two bonds defaults or (b) if both bonds default. The senior tranche does not pay out, only if both bonds default simultaneously (in the same year). Given our independence assumption, the probabilities for the number of defaults (D = default, N = no default) from our two bonds are given by the binomial model:

(in any year) and the correlation between defaults is zero (i.e. credit risks are independent). We now create two tranches, each containing $1 notional. The junior tranche does not pay out if (a) either one of the two bonds defaults or (b) if both bonds default. The senior tranche does not pay out, only if both bonds default simultaneously (in the same year). Given our independence assumption, the probabilities for the number of defaults (D = default, N = no default) from our two bonds are given by the binomial model:

The probability of no cash flows paid to the senior tranche is:

The probability of no cash flows paid to the junior tranche is:

The senior tranche has a lower probability of default (1%) than either of the two original bonds, which each have a probability of default of 10%. The senior tranche is genuinely less risky than the original bonds and the senior tranche may therefore warrant an AAA rating – this is credit enhancement. From our original $2 bond portfolio we have created a $1 face value senior tranche which is now AAA rated – we have ‘structured’ an increase in the degree of ‘credit enhancement’, covering 50% of the value of our original bond portfolio.

Notice that if the default correlation between the two bonds X and Y is ![]() then there would be no credit enhancement – when one bond defaults so does the other, so the probability of default for the senior tranche would be 10%, the same as for the individual bonds. Clearly, the lower the default correlations the greater the credit enhancement. The difficulty in assessing the riskiness of an ABS is therefore in forecasting these default correlations.

then there would be no credit enhancement – when one bond defaults so does the other, so the probability of default for the senior tranche would be 10%, the same as for the individual bonds. Clearly, the lower the default correlations the greater the credit enhancement. The difficulty in assessing the riskiness of an ABS is therefore in forecasting these default correlations.

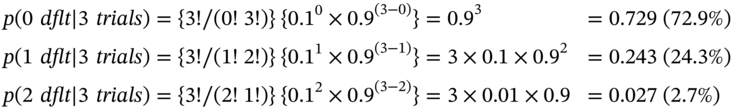

We can see how further tranches in the waterfall can lead to greater credit enhancement. Assume again uncorrelated defaults and we have $1 principal for each of three different BBB rated company bonds, each with a default probability of 10%. The probabilities for 0, 1, or 2 defaults using the binomial model are:

We now create three tranches with $1 notional in each tranche. The senior tranche pays out unless there are (exactly) 3 defaults, the mezzanine tranche pays out unless there are 2 or 3 defaults and the equity tranche pays out only if there are zero defaults. Hence:

- p(default for senior tranche:

- p(default) for mezzanine tranche: p(2 or more defaults)

- p(default junior tranche): p(1 or more defaults)

.

.

Out of our original $3 principal, we have structured two tranches with total face value of $2 that have a probability of default, less than the 10% default probability of each of the original bonds. We have created a 66.6% credit enhancement since we have 2 tranches worth $2 that have a lower risk of default than the original $3 worth of (non-securitised) bonds.

43.3 LOSSES ON ABS AND ABS-CDO

Now return to our initial ‘two-tranche’ example. Suppose we now take two independent junior tranches from two different ABSs, one of which was structured from credit card loans and the other from telephone receipts, each with a probability of default of 19% (Equation 43.2). These two junior tranches (from two different ABSs) are now themselves structured into senior and junior tranches. This is an ABS-CDO.

The senior tranche of the ABS-CDO receives no payments only if both junior tranches of the two ABSs default. So the probability of default for the ABS-CDO senior tranche is ![]() , which is substantially less than the probability of default of either of the two original junior ABS tranches (of 19%). Hence the senior ABS-CDO tranche will have a higher credit rating than either of the two junior ABS tranches and may be given an AAA rating.

, which is substantially less than the probability of default of either of the two original junior ABS tranches (of 19%). Hence the senior ABS-CDO tranche will have a higher credit rating than either of the two junior ABS tranches and may be given an AAA rating.

43.3.1 Regulatory Arbitrage

Why would a bank allow its structured products division to issue ABSs while also allowing its trading desk to purchase ABSs issued by other banks? For a bank, purchase of AAA-rated tranches could probably be financed at LIBOR, but AAA-tranches earn about LIBOR+120 bps in normal times – hence a bank's trading desk might buy these senior tranches (from other banks or pension funds) to increase profits on its own trading desk. Also the regulatory capital requirements for bank mortgages that are held by an originating bank in its ‘banking book’ are usually higher than the capital required if instead they hold ABS tranches of mortgages, which are classified as being on the ‘trading book’. Hence by originating and selling ABSs and then buying securitised ABSs (in the open market), banks might be able to reduce the levels of regulatory capital they have to hold – this is known as regulatory arbitrage. Hence in the run up to the 2008 crisis, one division of the bank might be securitising its bank loans and selling ABSs and ABS-CDOs (i.e. reducing credit risk), while the trading desk might be investing in them (i.e. increasing its credit risk). Hence, when the credit crunch hit in 2008, some banks found themselves in severe difficulties. We investigate this below.

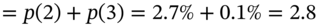

Figure 43.2 represent a simplified ABS and ABS-CDO each with 3 tranches. The underlying assets in the ABS-CDO might comprise sub-prime mortgages from the mezzanine tranche of an ABS. We assume the total face value of all the underlying mortgages is $100m. After the ‘waterfall’, the total of AAA-rated securities (senior tranches) in these two structures (the ABS and the ABS-CDO) is ![]() .

.

Consider the ABS tranches (Figure 43.2). The junior tranche takes the first 5% ($5m) hit and the ABS-Mezz tranche the next 20% of losses, which implies a maximum loss to the Mezz tranche of $20m. The Mezz tranche absorbs losses from 5% up to 25% of the $100m principal of the underlying bonds. The ABS-Senior tranche is likely to get its promised return of 6% if defaults on the underlying bonds are less than 25%.

However, the waterfall gives rise to levered losses. If a relatively small proportion of the underlying mortgages default then this leads to a relatively large loss in the equity and mezzanine tranches of the ABS and even substantial losses in the senior tranche of the ABS-CDO. We consider two cases – a loss of 10% and a loss of 20% in the underlying mortgages – and we investigate the consequences of these losses on the various tranches of the ABS and the ABS-CDO.

43.3.1.1 Case A: 10% Loss ($10m) on Sub-prime Mortgages

Of the $10m total loss on the mortgages, the ABS-equity tranche takes the first ‘hit’ of ![]() , the ABS-Mezz tranche takes the remaining hit of $5m which is

, the ABS-Mezz tranche takes the remaining hit of $5m which is ![]() of the value of this tranche's principal amount (Table 43.1). The ABS-Senior tranche takes no hit (0% loss).

of the value of this tranche's principal amount (Table 43.1). The ABS-Senior tranche takes no hit (0% loss).

TABLE 43.1 Losses on ABS and ABS-CDO

| Losses on subprime | ABS | ABS-CDO | ||||

| Losses on equity tranche | Losses on mezzanine tranche | Losses on senior tranche | Losses on equity tranche | Losses on mezzanine tranche | Losses on senior tranche | |

| 10% | 100% | 25% | 0% | 100% | 100% | 0% |

| 20% | 100% | 75% | 0% | 100% | 100% | 66.7% |

For the ABS-CDO equity-tranche the maximum loss is 5% of the $20m principal of the ABS-Mezz tranche, which amounts to $1m. For the ABS-CDO Mezz-tranche, the maximum loss is 20% of $20m, that is $4m. Hence the loss of $5m on the ABS-Mezz-tranche, wipes out all the principal in both the ABS-CDO equity-tranche ($1m principal, 100% loss) and ABS-CDO Mezz-tranche ($4m principal, 100% loss). But the senior-tranche of the ABS-CDO remains intact if the losses on the underlying sub-prime mortgages are 10% or less.

43.3.1.2 Case B: 20% Loss ($20m) on Sub-prime Mortgages

The loss on the mortgages is $20m. The first $5m loss accrues to the ABS equity tranche (i.e. 100% of principal of $5m) and the remaining $15m loss is absorbed by the ABS-Mezz tranche. But the latter has a principal of $20m, so the loss is ![]() of the principal of the ABS-Mezz tranche. The ABS-Senior tranche takes no losses (Figure 43.2).

of the principal of the ABS-Mezz tranche. The ABS-Senior tranche takes no losses (Figure 43.2).

The loss for the ABS-Mezz tranche is $15m. From the latter, the ABS-CDO equity tranche takes the first hit of $1m (100% of its principal of $1m) and the ABS-CDO Mezz tranche covers the next $4m of losses (100% of its principal of $4m). Hence the loss remaining for the ABS-CDO senior tranche is ![]() . But the principal in the ABS-CDO senior tranche is

. But the principal in the ABS-CDO senior tranche is ![]() . Hence the proportionate loss is

. Hence the proportionate loss is ![]() of principal value for the ABS-CDO senior tranche – quite substantial for a tranche that may have a credit rating of AAA.

of principal value for the ABS-CDO senior tranche – quite substantial for a tranche that may have a credit rating of AAA.

Looking across any row of Table 43.1 we can see that losses are ‘levered’ as we move from the percentage losses of the underlying mortgages themselves – the percentage losses on some of the ABS and ABS-CDO tranches is much higher.

For example, a 20% loss in value of the underlying mortgages gives rise to a 75% loss in the ABS-Mezz tranche and 100% loss in the ABS-CDO Mezz tranche. There is zero loss in the ABS senior tranche but a 66.7% loss in the ABS-CDO senior tranche. Of course both the ABS and ABS-CDO junior tranches lose 100% of their value, as they take the first hit.

In July 2008 Merrill Lynch sold $30.6bn AAA-rated senior tranches of CDO-squared to Loan Star funds for 22 cents on the dollar. When the value of this tranche fell to 16.5 cents on the dollar, Merrill had to (legally) take back these assets – this demonstrates the riskiness of these structured products and the complications surrounding whether they should appear ‘off-balance sheet’ or ‘on-balance sheet’.

43.4 SUB-PRIME CRISIS 2007–8

In the summer of 2007 the US was hit by the sub-prime mortgage crisis. Since 2000 and particularly over the period 2004–7 many US home owners had been given loans on 100% (or more) of the estimated value of the house. Some could not meet repayments, house prices in the US fell by around 30% on average, so the collateral underlying these loans was suspect. In consequence, major banks such as Merrills, Citygroup and UBS took ‘large losses’ on sub-prime loans they held ‘on-balance sheet’ and sometimes even greater losses on asset backed securities (with underlying sub-prime loans) that their trading divisions had purchased in the open market. Many of these ABSs were also held by other investors around the world such as pension funds and insurance companies.

Securitisation means that banks and S&Ls no longer ‘originate and hold’ mortgages but ‘originate and distribute’. Sub-prime refers to the fact that some mortgage pools contained mortgages issued to borrowers who had high credit risk (e.g. based on credit scoring models) and therefore had a high probability of default on repayments relative to ‘normal’ creditworthy borrowers. There is clearly an incentive for financial advisors to sell mortgages and hence earn commission. Prior to 2008 some mortgagees used ‘self-certification’, so their income was not checked by anyone and they may therefore have obtained mortgages that are very large in relation to their ‘true’ income. These were known as NINJA loans – as it was said that some of the mortgagees had ‘no income, no job and assets’. Other mortgages known as ‘2/28’ were used, where for the first 2 years of the mortgage there was a low ‘teaser’ rate of interest of say 3% p.a. but then the mortgage would switch to a high fixed rate (of say 6%) for the remaining 28 years.

Mortgages in some US states are ‘non-recourse’ – if the borrower defaults, the bank can only take possession of the house but not the borrower's other assets (e.g. stock portfolio). Hence you could have the bizarre situation where two houses currently worth $250,000, each have a mortgage of $300,000 but could only be sold in foreclosure for $200,000. It pays both mortgagees to default and purchase each other's houses, when they are in the foreclosure stage. As foreclosures increased (particularly if concentrated in particular neighbourhoods), this increased housing supply in specific local areas and put further downward pressure on house prices – exacerbating an already dire situation. When the housing market turned down in the US, partly as a result of the end of the ‘teaser rates’, investors in ABSs (sub-prime mortgages) suffered losses. Sometimes clauses in the securitisation documentation allowed investors to hand back their ABS tranches to the banks, if they had lost value very quickly.

In the crisis nobody wanted to purchase ABSs involving sub-prime mortgagees – this is because it is difficult to value assets that are not ‘transparent’. Their value depends on the economic position of a ‘pool’ of mortgagees, their ability to repay and the value of the house relative to the loan outstanding. Uncertainty about which banks were extensively involved in the sub-prime home loan market led to a liquidity crisis, as banks became wary of lending to each other in the 1-month and 3-month interbank market. Interbank rates (LIBOR) increased even though the Fed lowered its discount rate. As Warren Buffett commented on the use of ABS/CDOs: ‘One of the lessons that investors seem to have to learn over and over again, and will again in the future, is that not only can you not turn a toad into a prince by kissing it, but you cannot turn a toad into a prince by repackaging it’ (Financial Times, 26 October 2007).

In the middle the crisis, November 2007 saw the ‘retirement’ of Stan O'Neal, the boss of Merrill Lynch, when they announced prospective losses on sub-prime of $8bn. This was closely followed by the departure of Chuck Prince, the boss of Citygroup, who initially announced losses of between $8bn and $11bn on its sub-prime portfolio of around $60bn. UBS head Huw Jenkins also ‘stepped down’.

Some of the equity tranches of ABSs were purchased by hedge funds. But hedge funds tended to buy on margin, by borrowing funds from their prime broker (i.e. a bank) to buy the ABS-CDOs. In this case banks did not really spread the risks of their mortgage pools very much. If the ‘pool’ becomes ‘toxic waste’, the hedge fund cannot sell the ABS at a reasonable price and if the hedge fund is not able to pay back the interest and principal on its bank loan, then the bank itself is in trouble. If the hedge fund is a subsidiary of the bank (and the bank may have a part equity stake in the hedge fund) the bank may cross-subsidise any losses the hedge fund makes for some time, in order to preserve its ‘reputation’. Again this means that the bank still retains the risk of some of the ABSs it originated.

The senior tranches of sub-prime ABSs were given a AAA-rating by rating agencies and the latter have come under criticism because of their conflicts of interest. The ratings agencies are paid by the issuers of the ABS to provide a rating and hence may tend to give too high a rating in order to secure repeat business from the originator bank. Sometimes AAA-rated, ABSs turned out to be more dangerous than Class-A drugs – hence the term ‘toxic waste’.

The devastating consequences of the mix of credit risk and liquidity risk came to the fore in the UK in 2007–8 when the sub-prime mortgage crisis in the US spilled over into other countries – see Finance Blog 43.1.

43.5 SYNTHETIC CDO

If the assets being securitised and placed in tranches are bonds issued by corporations or countries then the ABS is referred to as a ‘cash CDO’. A long position in a corporate bond has the same credit risk as a short position in a CDS (written on the same bond) – if the company defaults both positions experience similar losses. The ‘short’ in a CDS contract receives periodic fixed payments but suffers a loss equal to the fall in value of the (reference) bond if it defaults – these cash flows are equivalent to a long position in a corporate bond. This implies that instead of forming a CDO from corporate bonds we can create a CDO using a portfolio of short positions in credit default swaps (CDS) – this is known as a synthetic CDO.

In a synthetic CDO, losses on the CDS are allocated to tranches. Suppose the total notional principal on a portfolio of CDS is $100m and there are three tranches. Suppose the tranches are as follows:

- Tranche-1 takes the first $5 million of losses and has a promised return of 15% on the remaining tranche-1 principal.

- Tranche-2 takes the next $30 million of losses and has a promised return of 200 bps (over LIBOR) on the remaining tranche-2 principal.

- Tranche-3 takes the next $65 million of losses and has a promised return of 20 bps (over LIBOR) on the remaining tranche-3 principal.

The synthetic CDO consists of these three tranches of the CDS. Initially tranche-1 earns 15% on the $5m principal. If after say 1 year, $2m of losses occur on the portfolio of CDS then the notional principal of tranche-1 is reduced by $2m – so the 15% return is earned only on the remaining $3 million (rather than $5m). When losses reach $5 million, tranche-1 ceases to exist and tranche-2 takes any further losses, and so on. For example, when total losses reach $10 million, the notional principal of tranche-2 is reduced to $25m (=$30m – $5m) and it receives 200 bps per annum on the reduced principal.

Investors in a synthetic CDO have to immediately post the initial tranche principal as collateral and this earns LIBOR. When there are defaults and the ‘short’ CDS has to pay out funds, money is taken from the collateral of the tranche which has experienced the defaults. If there is any recovery of a proportion of the loans/bonds in default, these are usually used to reduce the principal on the most senior tranche. From that point on, the senior tranche earns its promised return based on its new lower principal value. However, the senior tranche does not actually lose its future claim on the principal that is retired – it just does not earn a return on it.

43.6 SINGLE TRANCHE TRADING

A single tranche trade is simply an agreement to buy or sell protection against losses on particular designated ‘standard’ tranches, where these standard tranches are created from a portfolio of 125 companies that are used in the CDX and iTraxx indices. (Note that single tranche trading is not a synthetic CDO, which requires a portfolio of assets.)

How are these tranches created? For example, in the case of single tranche trading on the CDX index, the equity tranche covers losses between 0% and 3%, the second tranche (mezzanine) covers losses between 3% and 7% and the other tranche ‘coverage percentages’ are shown in Table 43.2.

TABLE 43.2 Five-year CDX and iTraxx single tranches

| Tranche | Equity | Mezzanine | Tranche | Tranche | Tranche | Min. risk tranche |

| Panel A : CDX – USA | ||||||

| Losses | 0–3% | 3–7% | 7–10% | 10–15% |

|

30–100% |

| Price quote | 26% | 101 bp | 20 bp | 10 bp | 4 bp | 2 bp |

| 400 bp | ||||||

| Panel B: iTraxx – Europe | ||||||

| Losses | 0–3% | 3–6% | 6–9% | 9–12% |

|

22–100% |

| Price quote | 11% | 58 bp | 14 bp | 7 bp | 3 bp | 1 bp |

| 400 bp | ||||||

Notes: Price quotes have day count ‘30/360’ and are in basis points. The equity tranche is quoted differently. The equity tranche payer pays 26% CDX-USA (or 11% iTraxx-Europe) of the principal, on the CDX (or iTraxx) index, at the initiation of the equity single tranche and then pays 400 bp per year thereafter.

The price quotes for each tranche are in basis points and have a day-count convention of ‘30/360’. But the equity tranche is quoted differently. The equity tranche payer on the CDX-USA index pays 26% of the notional principal (in the CDX index) at the initiation of the equity single tranche trade and then pays 400 bps per year thereafter. For the equity tranche on the iTraxx (Europe) index the equivalent figures are 11% of the principal (in the iTraxx index), at the initiation of the equity single tranche trade and then 400 bps per year thereafter.

43.6.1 Trader-A: Buys Protection on 7–10% CDX-tranche

To see how single tranche trading works, suppose trader-A buys protection over the next 5 years from trader-B for the ‘7–10% tranche’ on the CDX index for an amount of protection (notional principal) of $9m, with a spread payment of 20 bps per year (Table 43.2). Payouts from B to A depend on default losses on the CDX index. If the cumulative loss is less than 7% of the portfolio principal, there is no payout and trader-A pays ![]() p.a. to trader-B (this is usually paid each quarter in arrears). Suppose at the end of year-2 cumulative losses increase from 7% to 8% (i.e. 1/3 of the total range of 7–10% for this tranche), then trader-A will receive $3m (=1/3 of $9m) and the tranche principal is reduced to $6m.3

p.a. to trader-B (this is usually paid each quarter in arrears). Suppose at the end of year-2 cumulative losses increase from 7% to 8% (i.e. 1/3 of the total range of 7–10% for this tranche), then trader-A will receive $3m (=1/3 of $9m) and the tranche principal is reduced to $6m.3

From this point on, the 20 bps per year is paid on the reduced principal. If at the end of year-3 cumulative losses hit 10% then trader-A receives an additional $6m (and the 7–10% tranche principal is now ![]() ). Any subsequent losses over the final 2 years of the protection period, involve no further payments between these two counterparties.

). Any subsequent losses over the final 2 years of the protection period, involve no further payments between these two counterparties.

Note that if you purchase protection on the equity tranche of CDX, the quote is different and equal to ‘ ![]() ’. This means the protection seller (trader-B) receives an initial up-front payment of (26% × $9m) and then is entitled to receive 400 bps per year on any of the remaining tranche principal, throughout the life of the deal.

’. This means the protection seller (trader-B) receives an initial up-front payment of (26% × $9m) and then is entitled to receive 400 bps per year on any of the remaining tranche principal, throughout the life of the deal.

The pricing of ‘CDS tranches’ and synthetic CDOs is both technically and practically rather complex. This is because the quoted price depends on the expected default correlations between the underlying reference entities – these correlations are difficult to forecast, partly because we have so little data and partly because these correlations may not be constant over time.

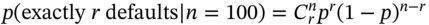

To get some idea of what is happening, assume you have 100 reference entities in the synthetic structure. Suppose the probability of any reference entity defaulting (over say 5 years) is 2% (in any one year) and the credit default correlation is zero (e.g. defaults are independent). The binomial model tells us that the probability of one or more defaults over the 5 years is 86.74%, while the probability of 10 or more defaults is 0.0034%.4 So a first-to-default CDS will cost a substantial amount, whereas a 10th-to-default CDS will cost much less.

So, if default correlations are low, the junior tranches of a synthetic CDO are very risky and therefore relatively expensive, but the senior tranches are very safe and it is relatively cheap to purchase protection. To take the other extreme, if the default correlation between all the reference entities is +1, the probability of one or more defaults is the same as the probability of exactly 2, 3, 4,…., 99 or 100 defaults and all these probabilities equal 2%. So all tranches are equally risky and all have the same price. The price of the synthetic CDO depends on the correlations between defaults and these are difficult to forecast accurately.

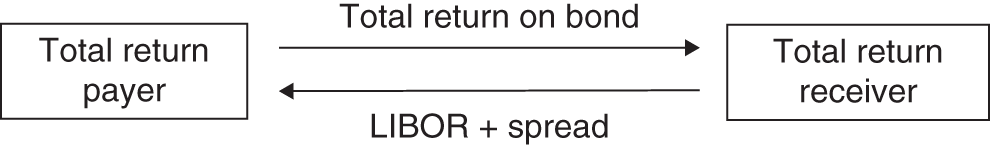

43.7 TOTAL RETURN SWAP

A total return swap (TRS) can be used for hedging the total risk (i.e. market plus credit risk) of a corporate bond. We assume the payer in the TRS already owns the corporate bond. In a total return swap the payer agrees to pay the total return on an asset (e.g. 10-year corporate bond) and to receive LIBOR plus a spread (Figure 43.3). The total return receiver is the counterparty.

FIGURE 43.3 Total return swap

Suppose the reference asset is a 10-year corporate bond. Then a TRS with a life of 5 years and a notional principle of $10m, would involve periodic payments of the bond coupons (e.g. every 6 months) by the total return payer and receipt of LIBOR+30 bps (say) over the 5 years. LIBOR is determined on a coupon payment date and paid out at the next coupon (reset) date, as in a standard interest rate swap. At maturity of the TRS there is also a payment reflecting the change in value of the bond over the life of the TRS.

For example, if the 10-year bond increases in value by 10% over the 5-year life of the TRS, the total return payer will pay out $1m at the end of 5 years. But if the bond decreases in value by 10%, the total return receiver will pay $1m to the ‘TRS payer’. Before the maturity date of the total return swap there may be a default on the reference bond. At this point, the swap is usually terminated and the swap receiver makes a payment equal to ‘$10m less the market price of the bond’ at default.

There are variants on the above. For example, cash flows arising from any change in the market value of the bond may be made periodically rather than at maturity of the TRS. Also instead of a cash payment for the change in value of the bond at maturity of the TRS, there may be ‘physical settlement’ – the total return payer delivers the (reference) bond and receives cash equal to the notional principal of the TRS.

A TRS can be used for hedging credit risk, if the TRS-payer already owns the corporate bond. The credit risk is passed on to the TRS-receiver, while the TRS-payer has a net receipt of LIBOR+30 bps, independent of what happens to the bond price due to changes in credit risk. If the TRS-payer does not own the bond, the TRS-payer is effectively ‘short’ the corporate bond. For example, the TRS-payer will have to pay the coupons each period and if the bond price rises by say 10%, the TRS-payer will pay out 10% of the (par) value of the bond (at maturity of the TRS).

The TRS-payer loses money if the counterparty (i.e. the TRS-receiver) defaults any time after the reference bond's price has declined, and the spread over LIBOR is compensation for this risk. The ‘spread-over-LIBOR’ is therefore determined by the credit quality of both the bond issuer and the receiver in the TRS, as well as the credit correlation between the two. The receiver in a TRS with principal Q = $10m can also be viewed as owning a bond, financed by a loan at LIBOR+30 bps.

43.8 SUMMARY

- Asset backed securities (ABSs) are marketable securities where future payments depend on cash flows from a specific source (e.g. credit card receipts, rents from property or payments by mortgage holders). If the cash flows are from (underlying) fixed-income assets (e.g. mortgages, corporate loans) then the ABS is known as a collateralised debt obligation (CDO). The structuring of ABSs and CDOs is known as securitisation.

- In an ABS, cash flows are assigned to ‘tranches’ and each tranche receives its cash flows in a particular priority order (‘the waterfall’). The senior tranche is paid first, followed by the mezzanine tranches and finally the equity tranche is paid (if funds are available). Hence the ABS is structured so the senior tranche has less credit risk than the other tranches (and less credit risk than the underlying loans/bonds) – this is ‘credit enhancement’. The super-senior and senior tranches are usually given a AAA credit rating.

- The mezzanine tranches from several different ABSs can also be subject to ‘a waterfall’, which gives rise to an ‘ABS-CDO’ (also referred to as a CDO-squared).

- The default risk of ABSs and ABS-CDOs are difficult to forecast because they depend on the individual default risks of a large number of underlying borrowers and the correlation between defaults across these borrowers.

- Default by a relatively small proportion of the underlying assets (e.g. bank loans, mortgagees) can cause much larger proportionate losses for the mezzanine tranches of an ABS and even larger losses for the mezzanine tranches of an ABS-CDO. Even losses in the AAA-rated senior (or super-senior) tranches of both the ABS and ABS-CDOs are possible. This ‘leverage effect’ was the proximate cause of the difficulties faced by many banks in the credit crunch of 2008–9, when the US sub-prime home loan market collapsed.

- A ‘synthetic-CDO’ consists of tranches formed from short positions in credit default swap (CDS) contracts. As with ‘cash-market’ CDOs, each tranche of a synthetic-CDO takes losses in a specific order, the equity tranche takes the first losses (and has the highest promised return), followed by the mezzanine and senior tranches.

- In ‘single-tranche trading’ you can buy and sell ‘tranches’ of credit risk. For example, suppose you buy a 5-year, 7–10% single-tranche CDS on iTraxx. Then you are buying protection over the next 5 years on losses (for the 125 companies in the index) of between 7% and 10% of the agreed notional principal. This insurance against losses may cost you 200 bps per year of the notional principal (but payments cease once cumulative losses exceed 10% of the principal).

- The buyer of a total return swap (TRS) agrees to pay the total return on a reference bond – that is, the periodic coupon payments and any change in the market price of the bond, which takes place from inception and the maturity date of the TRS. Also, the buyer of the TRS receives LIBOR plus a spread (on the notional principal in the TRS contract). If an investor already holds a corporate bond, then a long position in a TRS can be used for hedging market and credit risk on the bond (i.e. ‘the reference entity’).

EXERCISES

Question 1

What is securitisation?

Question 2

What is tranching or a ‘waterfall’?

Question 3

Explain how an ABS-CDO (or CDO-squared) works.

Question 4

If the correlation between bond-defaults increases, explain what happens to the risk of the senior tranche of an ABS. Assume the senior tranche has only two bonds and each bond has a probability of default (over the next year) of 10%. In your answer, first assume zero correlation between two bond prices that are in the senior tranche and then a correlation coefficient of +1.

Question 5

You have two bonds where the probability of default (over the next year) for each bond is ![]() . Credit risks on the two bonds are independent so the correlation between defaults is zero. Each bond has par value of $1. Structure these two bonds into a senior and a junior tranche and calculate the default probabilities of each tranche and demonstrate any ‘credit enhancement’.

. Credit risks on the two bonds are independent so the correlation between defaults is zero. Each bond has par value of $1. Structure these two bonds into a senior and a junior tranche and calculate the default probabilities of each tranche and demonstrate any ‘credit enhancement’.

Question 6

What is a total return swap and how can it be used to hedge a corporate bond?

Question 7

What is a sub-prime mortgage?

NOTES

- 1 In the 2008 credit crunch these equity tranches were often referred to as ‘toxic waste’.

- 2 Alternatively we can use the binomial model directly:

.

. - 3 Although here we are describing single tranche trading and not a synthetic CDO, it is worth noting that this is also the way in which cash flows are calculated in a synthetic CDO.

- 4

.

.  , where

, where  . and p = probability of default.

. and p = probability of default.