Direction of Communication

Communication can flow vertically or laterally, through formal small-group networks or the informal grapevine. We subdivide the vertical dimension into downward and upward directions.5

Downward Communication

Communication that flows from one level of a group or organization to a lower level is downward communication. Group leaders and managers use it to assign goals, provide job instructions, explain policies and procedures, point out problems that need attention, and offer feedback.

In downward communication, the delivery mode and the context of the information are of high importance. We will talk more about communication methods later, but consider the ultimate downward communication: the performance review. Alan Buckelew, CEO of Carnival Cruise Lines says, “A review is probably the one time when you want to be physically present.” The Samsonite CEO agrees: “A conference call cannot substitute for face-to-face interactions.” Automated performance reviews have allowed managers to review their subordinates without discussions, which is efficient but misses critical opportunities for growth, motivation, and relationship-building.6 In general, employees subjected to less direct, personalized communication are less likely to understand the intentions of the message correctly. The best communicators explain the reasons behind their downward communications but also solicit communication from the employees they supervise.

Upward Communication

Upward communication flows to a higher level in the group or organization. It’s used to provide feedback to higher-ups, inform them of progress toward goals, and relay current problems. Upward communication keeps managers aware of how employees feel about their jobs, coworkers, and the organization in general. Managers also rely on upward communication for ideas on how conditions can be improved.

Given that most managers’ job responsibilities have expanded, upward communication is increasingly difficult because managers can be overwhelmed and easily distracted. To engage in effective upward communication, try to communicate in short summaries rather than long explanations, support your summaries with actionable items, and prepare an agenda to make sure you use your boss’s attention well.7 And watch what you say, especially if you are communicating something to your manager that will be unwelcome. If you’re turning down an assignment, for example, be sure to project a “can do” attitude while asking advice about your workload dilemma or inexperience with the assignment.8 Your delivery can be as important as the content of your communication.

Lateral Communication

When communication occurs between members of the same workgroup, members at the same level in separate workgroups, or any other horizontally equivalent workers, we describe it as lateral communication.

Lateral communication saves time and facilitates coordination. Some lateral relationships are formally sanctioned. More often, they are informally created to short-circuit the vertical hierarchy and expedite action. So from management’s viewpoint, lateral communications can be good or bad. Because strictly adhering to the formal vertical structure for all communications can be inefficient, lateral communication occurring with management’s knowledge and support can be beneficial. But dysfunctional conflict can result when formal vertical channels are breached, when members go above or around their superiors, or when bosses find actions have been taken or decisions made without their knowledge.

Formal Small-Group Networks

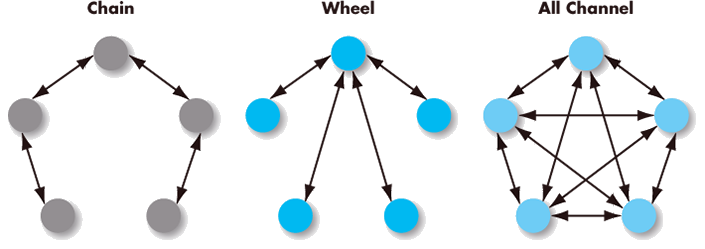

Formal organizational networks can be complicated, including hundreds of people and a half-dozen or more hierarchical levels. We’ve condensed these networks into three common small groups of five people each (see Exhibit 11-2): chain, wheel, and all channel.

Exhibit 11-2

Three Common Small Group Networks

The chain rigidly follows the formal chain of command; this network approximates the communication channels you might find in a rigid three-level organization. The wheel relies on a central figure to act as the conduit for all group communication; it simulates the communication network you might find on a team with a strong leader. The all-channel network permits group members to actively communicate with each other; it’s most often characterized by self-managed teams, in which group members are free to contribute and no one person takes on a leadership role. Many organizations today like to consider themselves all channel, meaning that anyone can communicate with anyone (but sometimes they shouldn’t).

As Exhibit 11-3 demonstrates, the effectiveness of each network is determined by the dependent variable that concerns you. The structure of the wheel facilitates the emergence of a leader, the all-channel network is best if you desire high member satisfaction, and the chain is best if accuracy is most important. Exhibit 11-3 leads us to the conclusion that no single network will be best for all occasions.

Exhibit 11-3

Small Group Networks and Effectiveness Criteria

The Grapevine

The informal communication network in a group or organization is called the grapevine.9 Although rumors and gossip transmitted through the grapevine may be informal, it’s still an important source of information for employees and candidates. Grapevine or word-of-mouth information from peers about a company has important effects on whether job applicants join an organization,10 even over and above informal ratings on websites like Glassdoor.

The grapevine is an important part of any group or organization communication network. It serves employees’ needs: small talk creates a sense of closeness and friendship among those who share information, although research suggests it often does so at the expense of those in the outgroup.11 It also gives managers a feel for the morale of their organization, the issues employees consider important, and employee anxieties. Evidence indicates that managers can study the gossip driven largely by employee social networks to learn more about how positive and negative information is flowing through the organization.12 Furthermore, managers can identify influencers (highly networked people trusted by their coworkers13) by noting which individuals are small talkers (those who regularly communicate about insignificant, unrelated issues). Small talkers tend to be influencers. One study found that social talkers are so influential that they were significantly more likely to retain their jobs during layoffs.14 Thus, while the grapevine may not be sanctioned or controlled by the organization, it can be understood and leveraged a bit.