A Definition of Conflict

There has been no shortage of definitions of conflict,1 but common to most is the idea that conflict is a perception of differences or opposition. If no one is aware of a conflict, then it is generally agreed no conflict exists. Opposition or incompatibility, as well as interaction, are also needed to begin the conflict process.

We define conflict broadly as a process that begins when one party perceives another party has affected or is about to negatively affect something the first party cares about. Conflict describes the point in ongoing activity when interaction becomes disagreement. People experience a wide range of conflicts in organizations over an incompatibility of goals, differences in interpretations of facts, disagreements over behavioral expectations, and the like. Our definition covers the full range of conflict levels, from overt and violent acts to subtle forms of disagreement.

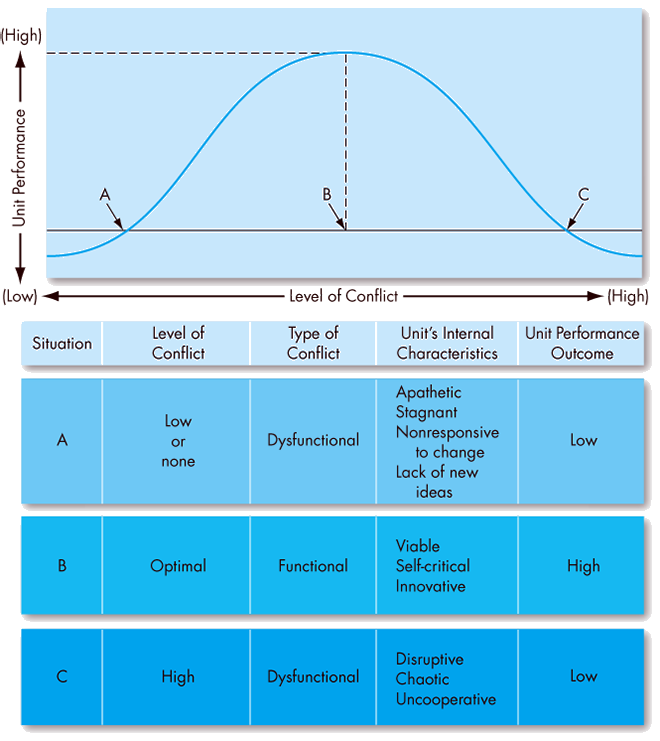

Contemporary perspectives differentiate types of conflict based on their effects. Functional conflict supports the goals of the group and improves its performance, and is thus a constructive form of conflict. For example, a debate among members of a work team about the most efficient way to improve production can be functional if unique points of view are discussed and compared openly. Conflict that hinders group performance is destructive or dysfunctional conflict. A highly personal struggle for control that distracts from the task at hand in a team is dysfunctional. Exhibit 14-1 provides an overview depicting the effect of levels of conflict. To understand different types of conflict, we will discuss next the types of conflict and the loci of conflict.

Exhibit 14-1

The Effect of Levels of Conflict

Types of Conflict

One means of understanding conflict is to identify the type of disagreement, or what the conflict is about. Is it a disagreement about goals? Is it about people who just rub one another the wrong way? Or is it about the best way to get things done? Although each conflict is unique, researchers have classified conflicts into three categories: relationship, task, or process. Relationship conflict focuses on interpersonal relationships. Task conflict relates to the content and goals of the work. Process conflict is about how the work gets done.

Relationship Conflict

Studies demonstrate that relationship conflicts, at least in work settings, are almost always dysfunctional. Why? It appears that the friction and interpersonal hostilities inherent in relationship conflicts increase personality clashes and decrease mutual understanding, which hinders the completion of organizational tasks. Of the three types, relationship conflicts also appear to be the most psychologically exhausting to individuals. Because they tend to revolve around personalities, you can see how relationship conflicts can become destructive. After all, we can’t expect to change our coworkers’ personalities, and we would generally take offense at criticisms directed at who we are as opposed to how we behave.

Task Conflict

While scholars agree that relationship conflict is dysfunctional, there is considerably less agreement about whether task and process conflicts are functional. Early research suggested that task conflict within groups correlated to higher group performance, but a review of 116 studies found that generalized task conflict was essentially unrelated to group performance. However, close examination revealed that task conflict among top management teams was positively associated with performance, whereas conflict lower in the organization was negatively associated with group performance, perhaps because people in top positions may not feel as threatened in their organizational roles by conflict. This review also found that it mattered whether other types of conflict were occurring at the same time. If task and relationship conflict occurred together, task conflict more likely was negative, whereas if task conflict occurred by itself, it more likely was positive. Other scholars have argued that the strength of conflict is important: if task conflict is very low, people aren’t really engaged or addressing the important issues; if task conflict is too high, infighting will quickly degenerate into relationship conflict. Moderate levels of task conflict may thus be optimal. Supporting this argument, one study in China found that moderate levels of task conflict in the early development stage increased creativity in groups, but high levels decreased team performance.2

Finally, the personalities of the teams appear to matter. One study demonstrated that teams of individuals who are, on average, high in openness and emotional stability are better able to turn task conflict into increased group performance. The reason may be that open and emotionally stable teams can put task conflict in perspective and focus on how the variance in ideas can help solve the problem, rather than letting it degenerate into relationship conflicts.

Process Conflict

What about process conflict? Researchers found that process conflicts are about delegation and roles. Conflicts over delegation often revolve around the perception that some members as shirking, and conflicts over roles can leave some group members feeling marginalized. Thus, process conflicts often become highly personalized and quickly devolve into relationship conflicts. It’s also true, of course, that arguing about how to do something takes time away from actually doing it. We’ve all been part of groups in which the arguments and debates about roles and responsibilities seem to go nowhere.

Loci of Conflict

Another way to understand conflict is to consider its locus, or the framework within which the conflict occurs. Here, too, there are three basic types. Dyadic conflict is conflict between two people. Intragroup conflict occurs within a group or team. Intergroup conflict is conflict between groups or teams.

Nearly all the literature on relationship, task, and process conflicts considers intragroup conflict (within the group). That makes sense given that groups and teams often exist only to perform a particular task. However, it doesn’t necessarily tell us all we need to know about the context and outcomes of conflict. For example, research has found that for intragroup task conflict to positively influence performance within the team, it is important that the team has a supportive climate in which mistakes aren’t penalized and every team member “[has] the other’s back.”3 But is this concept applicable to the effects of intergroup conflict? Think about, say, NFL football. As we said, for a team to adapt and improve, perhaps a certain amount of intragroup conflict (but not too much) is good for team performance, especially when the team members support one another. But would we care whether members from one team supported members from another team? Probably not. In fact, if groups are competing with one another so that only one team can “win,” conflict seems almost inevitable. Still, it must be managed. Intense intergroup conflict can be quite stressful to group members and might well affect the way they interact. One study found, for example, that high levels of conflict between teams caused individuals to focus on complying with norms within their teams.4

It may surprise you how certain individuals become most important during intergroup conflicts. One study that focused on intergroup conflict found an interplay between an individual’s position within a group and the way that individual managed conflict between groups. Group members who were relatively peripheral in their own group were better at resolving conflicts between their group and another one. But this happened only when those peripheral members were still accountable to their groups, and the effect can be confounded by dyadic conflicts.5 Thus, being at the core of your work group does not necessarily make you the best person to manage conflict with other groups.

Altogether, understanding functional and dysfunctional conflict requires not only that we identify the type of conflict; we also need to know where it occurs. It’s possible that while the concepts of relationship, task, and process conflicts are useful in understanding intragroup or even dyadic conflict, they are less useful in explaining the effects of intergroup conflict. But how do we make conflict as productive as possible? A better understanding of the conflict process, discussed next, will provide insight about potential controllable variables.