Challenges and Opportunities for OB

Understanding organizational behavior has never been more important for managers. Take a quick look at the dramatic changes in organizations. The typical employee is getting older; the workforce is becoming increasingly diverse; and global competition requires employees to become more flexible and cope with rapid change.

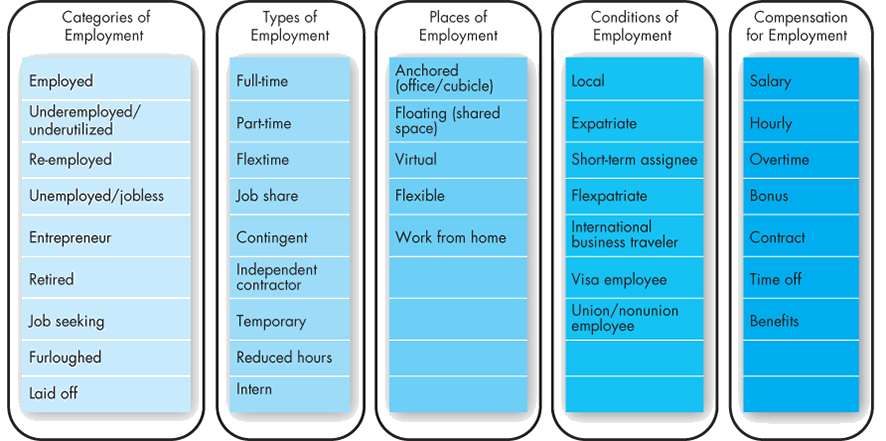

As a result of these changes and others, employment options have adapted to include new opportunities for workers. Exhibit 1-2 details some of the types of options individuals may find offered to them by organizations or for which they would like to negotiate. Under each heading in the exhibit, you will find a grouping of options from which to choose—or combine. For instance, at one point in your career you may find yourself employed full time in an office in a localized, nonunion setting with a salary and bonus compensation package, while at another point you may wish to negotiate for a flextime, virtual position and choose to work from overseas for a combination of salary and extra paid time off.

Exhibit 1-2

Employment Options

Sources: J.R. Anderson Jr., et al., “Action Items: 42 Trends Affecting Benefits, Compensation, Training, Staffing and Technology,” HR Magazine (January 2013) p. 33; M. Dewhurst, B. Hancock, and D. Ellsworth, “Redesigning Knowledge Work,” Harvard Business Review (January-February 2013), 58–64; E. Frauenheim, “Creating a New Contingent Culture,“ Workforce Management (August 2012), 34–39; N. Koeppen, “State Job Aid Takes Pressure off Germany,” The Wall Street Journal (february 1, 2013), p. A8; and M. A. Shaffer, M. L. Kraimer, Y,-P. Chen, and M.C. Bolino, “Choices, Challenges, and Career Consequences of Global Work Experiences: A Review and Future Agenda,” Journal of Management (July 2012), 1282–1327.

In short, today’s challenges bring opportunities for managers to use OB concepts. In this section, we review some—but not nearly all—of the critical developing issues confronting managers for which OB offers solutions or, at least, meaningful insights toward solutions.

Continuing Globalization

![]() Organizations are no longer constrained by national borders. Samsung, the largest South Korean business conglomerate, sells most of its products to organizations in other countries; Burger King is owned by a Brazilian firm; and McDonald’s sells hamburgers in 118 countries on 6 continents. Even Apple—arguably the U.S. company with the strongest U.S. identity—employs twice as many workers outside the United States as it does inside the country. And all major automobile makers now manufacture cars outside their borders; Honda builds cars in Ohio, Ford in Brazil, Volkswagen in Mexico, and both Mercedes and BMW in the United States and South Africa. The world has become a global village. In the process, the manager’s job has changed. Effective managers anticipate and adapt their approaches to the global issues we discuss next.

Organizations are no longer constrained by national borders. Samsung, the largest South Korean business conglomerate, sells most of its products to organizations in other countries; Burger King is owned by a Brazilian firm; and McDonald’s sells hamburgers in 118 countries on 6 continents. Even Apple—arguably the U.S. company with the strongest U.S. identity—employs twice as many workers outside the United States as it does inside the country. And all major automobile makers now manufacture cars outside their borders; Honda builds cars in Ohio, Ford in Brazil, Volkswagen in Mexico, and both Mercedes and BMW in the United States and South Africa. The world has become a global village. In the process, the manager’s job has changed. Effective managers anticipate and adapt their approaches to the global issues we discuss next.

Working with People from Different Cultures

In your own country or on foreign assignment, you’ll find yourself working with bosses, peers, and other employees born and raised in different cultures. What motivates you may not motivate them. Or your communication style may be straightforward and open, which others may find uncomfortable and threatening. To work effectively with people from different cultures, you need to understand how their culture and background have shaped them and how to adapt your management style to fit any differences.

Adapting to Differing Cultural and Regulatory Norms

![]() To be effective, managers need to know the cultural norms of the workforce in each country where they do business. For instance, in some countries a large percentage of the workforce enjoys long holidays. There are national and local regulations to consider, too. Managers of subsidiaries abroad need to be aware of the unique financial and legal regulations applying to “guest companies” or else risk violating them. Violations can have implications for their operations in that country and also for political relations between countries. Managers also need to be cognizant of differences in regulations for competitors in that country; many times, understanding the laws can lead to success or failure. For example, knowing local banking laws allowed one multinational firm—the Bank of China—to seize control of a storied (and very valuable) London building, Grosvenor House, from under the nose of the owner, the Indian hotel group Sahara. Management at Sahara contended that the loan default that led to the seizure was a misunderstanding regarding one of their other properties in New York.26 Globalization can get complicated.

To be effective, managers need to know the cultural norms of the workforce in each country where they do business. For instance, in some countries a large percentage of the workforce enjoys long holidays. There are national and local regulations to consider, too. Managers of subsidiaries abroad need to be aware of the unique financial and legal regulations applying to “guest companies” or else risk violating them. Violations can have implications for their operations in that country and also for political relations between countries. Managers also need to be cognizant of differences in regulations for competitors in that country; many times, understanding the laws can lead to success or failure. For example, knowing local banking laws allowed one multinational firm—the Bank of China—to seize control of a storied (and very valuable) London building, Grosvenor House, from under the nose of the owner, the Indian hotel group Sahara. Management at Sahara contended that the loan default that led to the seizure was a misunderstanding regarding one of their other properties in New York.26 Globalization can get complicated.

Workforce Demographics

![]() The workforce has always adapted to variations in the economy, longevity, birth rates, socioeconomic conditions, and other changes that have a widespread impact. People adapt to survive, and OB studies the way those adaptations affect individuals’ behavior. For instance, even though the 2008 global recession ended years ago, some trends from those years are continuing: many people who have been long unemployed have left the workforce,27 while others have cobbled together several part-time jobs28 or settled for on-demand work.29 Further options that have been particularly popular for younger educated workers have included obtaining specialized industry training after college,30 accepting full-time jobs that are lower-level,31 and starting their own companies.32 As students of OB, we can investigate what factors lead employees to make various choices and how their experiences affect their perceptions of their workplaces. In turn, this can help us predict organizational outcomes.

The workforce has always adapted to variations in the economy, longevity, birth rates, socioeconomic conditions, and other changes that have a widespread impact. People adapt to survive, and OB studies the way those adaptations affect individuals’ behavior. For instance, even though the 2008 global recession ended years ago, some trends from those years are continuing: many people who have been long unemployed have left the workforce,27 while others have cobbled together several part-time jobs28 or settled for on-demand work.29 Further options that have been particularly popular for younger educated workers have included obtaining specialized industry training after college,30 accepting full-time jobs that are lower-level,31 and starting their own companies.32 As students of OB, we can investigate what factors lead employees to make various choices and how their experiences affect their perceptions of their workplaces. In turn, this can help us predict organizational outcomes.

Longevity and birth rates have also changed the dynamics in organizations. Global longevity rates have increased by six years in a very short time (since 1990),33 while birth rates are decreasing for many developed countries; trends that together indicate a lasting shift toward an older workforce. OB research can help explain what this means for employee attitudes, organizational culture, leadership, structure, and communication. Finally, socioeconomic shifts have a profound effect on workforce demographics. For example, the days when women stayed home because it was expected are just a memory in some cultures, while in others, women face significant barriers to entry into the workforce. We are interested in how these women fare in the workplace, and how their conditions can be improved. This is just one illustration of how cultural and socioeconomic changes affect the workplace, but it is one of many. We discuss how OB can provide understanding and insight on workforce issues throughout this text.

Workforce Diversity

One of the most important challenges for organizations is workforce diversity, a trend by which organizations are becoming more heterogeneous in terms of employees’ gender, age, race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, and other characteristics. Managing this diversity is a global concern. Though we have more to say about it in the next chapter, suffice it to say here that diversity presents great opportunities and poses challenging questions for managers and employees. How can we leverage differences within groups for competitive advantage? Should we treat all employees alike? Should we recognize individual and cultural differences? What are the legal requirements in each country? Does increasing diversity even matter? It is important to address the spoken and unspoken concerns of organizations today.

Social Media

As we discuss in Chapter 11, social media in the business world is here to stay. Despite its pervasiveness, many organizations continue to struggle with employees’ use of social media in the workplace. For instance, in February 2015, a Texas pizzeria fired an employee before her first day of work because she tweeted unflattering comments about her future job. In December 2014, Nordstrom fired an Oregon employee who had posted a personal Facebook comment seeming to advocate violence against white police officers.34 These examples show that social media is a difficult issue for today’s managers, presenting both a challenge and an opportunity for OB. For instance, how much should HR look into a candidate’s social media presence? Should a hiring manager read the candidate’s Twitter feeds, or just do a quick perusal of his or her Facebook profile? Managers need to adopt policies designed to protect employees and their organizations with balance and understanding.

Once employees are on the job, many organizations have policies about accessing social media at work—when, where, and for what purposes. But what about the impact of social media on employee well-being? One recent study found that subjects who woke up in a positive mood and then accessed Facebook frequently found their mood worsened during the day. Moreover, subjects who checked Facebook frequently over a two-week period reported a decreased level of satisfaction with their lives.35 Managers—and OB—are trying to increase employee satisfaction, and therefore improve and enhance positive organizational outcomes. We discuss these issues further in Chapters 3 and 4.

Employee Well-Being at Work

One of the biggest challenges to maintaining employee well-being is the reality that many workers never get away from the virtual workplace. while communication technology allows many technical and professional employees to do their work at home, in their cars, or on the beach in Tahiti, it also means many feel like they’re not part of a team. “The sense of belonging is very challenging for virtual workers, who seem to be all alone out in cyberland,” said Ellen Raineri of Kaplan University, and many can relate to this feeling.36 Another challenge is that organizations are asking employees to put in longer hours. According to one recent study, one in four employees shows signs of burnout, and two in three report high stress levels and fatigue.37 This may actually be an underestimate because workers report maintaining “always on” access for their managers through e-mail and texting. Finally, employee well-being is challenged by heavy outside commitments. Millions of single-parent employees and employees with dependent parents face significant challenges in balancing work and family responsibilities, for instance.

As you’ll see in later chapters, the field of OB offers a number of suggestions to guide managers in designing workplaces and jobs that can help employees deal with work–life conflicts.

Positive Work Environment

A growing area in OB research is positive organizational scholarship (POS; also called positive organizational behavior), which studies how organizations develop human strengths, foster vitality and resilience, and unlock potential. Researchers in this area say too much of OB research and management practice has been targeted toward identifying what’s wrong with organizations and their employees. In response, they try to study what’s good about them.38 Some key subjects in positive OB research are engagement, hope, optimism, and resilience in the face of strain. Researchers hope to help practitioners create positive work environments for employees.

Although positive organizational scholarship does not deny the value of the negative (such as critical feedback), it does challenge researchers to look at OB through a new lens and pushes organizations to make use of employees’ strengths rather than dwell on their limitations. One aspect of a positive work environment is the organization’s culture, the topic of Chapter 16. Organizational culture influences employee behavior so strongly that organizations have employed “culture officers” to shape and preserve the company’s personality.39

Ethical Behavior

In an organizational world characterized by cutbacks, expectations of increasing productivity, and tough competition; it’s not surprising many employees feel pressured to cut corners, break rules, and engage in other questionable practices. Increasingly they face ethical dilemmas and ethical choices in which they are required to identify right and wrong conduct. Should they “blow the whistle” if they uncover illegal activities in their companies? Do they follow orders with which they don’t personally agree? Should they “play politics” to advance their careers?

What constitutes good ethical behavior has never been clearly defined and, in recent years, the line differentiating right from wrong has blurred. We see people all around us engaging in unethical practices—elected officials pad expense accounts or take bribes; corporate executives inflate profits to cash in lucrative stock options; and university administrators look the other way when winning coaches encourage scholarship athletes to take easy courses or even, in the recent case at the University of North Carolina–Chapel Hill, sham courses with fake grades.40 When caught, we see people give excuses such as “Everyone does it” or “You have to seize every advantage.”

Today’s manager must create an ethically healthy climate for employees in which they can do their work productively with minimal ambiguity about right and wrong behaviors. Companies that promote a strong ethical mission, encourage employees to behave with integrity, and provide strong leadership can influence employee decisions to behave ethically.41 Classroom training sessions in ethics have also proven helpful in maintaining a higher level of awareness of the implications of employee choices as long as the training sessions are given on an ongoing basis.42 In upcoming chapters, we discuss the actions managers can take to create an ethically healthy climate and help employees sort through ambiguous situations.