Why Do Structures Differ?

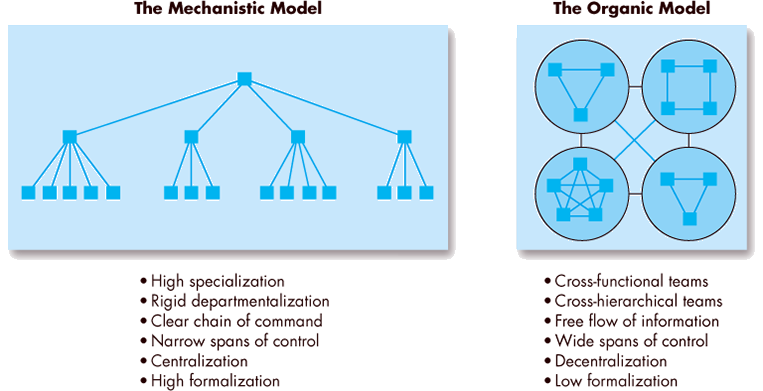

We’ve described many organization design options. Exhibit 15-6 recaps our discussions by presenting two extreme models of organizational design. One we call the mechanistic model. It’s generally synonymous with the bureaucracy in that it has highly standardized processes for work, high formalization, and more managerial hierarchy. The other extreme is the organic model. It’s flat, has fewer formal procedures for making decisions, has multiple decision makers, and favors flexible practices.33

Exhibit 15-6

Mechanistic vs. Organic Models

With these two models in mind, let’s ask a few questions: Why are some organizations structured along more mechanistic lines whereas others follow organic characteristics? What forces influence the choice of design? In this section, we present major causes or determinants of an organization’s structure.34

Organizational Strategies

Because structure is a means to achieve objectives, and objectives derive from the organization’s overall strategy, it’s only logical that structure should follow strategy. If management significantly changes the organization’s strategy or its values, the structure must also change to accommodate. For example, recent research indicates that aspects of organizational culture may influence the success of CSR initiatives.35 If the culture is supported by the structure, the initiatives are more likely to have clear paths toward application. Most current strategy frameworks focus on three strategy dimensions—innovation, cost minimization, and imitation—and a structural design that works best with each.36

Innovation Strategy

To what degree does an organization introduce major new products or services? An innovation strategy strives to achieve meaningful and unique innovations. Obviously, not all firms pursue innovation. Apple and 3M do, but conservative retailer Marks & Spencer doesn’t. Innovative firms use competitive pay and benefits to attract top candidates and motivate employees to take risks. Some degree of the mechanistic structure can actually benefit innovation. Well-developed communication channels, policies for enhancing long-term commitment, and clear channels of authority all may make it easier for rapid changes to occur smoothly.

Cost-Minimization Strategy

An organization pursuing a cost-minimization strategy tightly controls costs, refrains from incurring unnecessary expenses, and cuts prices in selling a basic product. This describes the strategy pursued by Walmart and the makers of generic or store-label grocery products. Cost-minimizing organizations usually pursue fewer policies meant to develop commitment among their workforce.

Imitation Strategy

![]() Organizations following an imitation strategy try to both minimize risk and maximize opportunity for profit, moving new products or entering new markets only after innovators have proven their viability. Mass-market fashion manufacturers that copy designer styles follow this strategy, as do firms such as Hewlett-Packard and Caterpillar. They follow smaller and more innovative competitors with superior products, but only after competitors have demonstrated the market is there. Italy’s Moleskine SpA, a small maker of fashionable notebooks, is another example of imitation strategy but in a different way: looking to open more retail shops around the world, it imitates the expansion strategies of larger, successful fashion companies Salvatore Ferragamo SpA and Brunello Cucinelli.37

Organizations following an imitation strategy try to both minimize risk and maximize opportunity for profit, moving new products or entering new markets only after innovators have proven their viability. Mass-market fashion manufacturers that copy designer styles follow this strategy, as do firms such as Hewlett-Packard and Caterpillar. They follow smaller and more innovative competitors with superior products, but only after competitors have demonstrated the market is there. Italy’s Moleskine SpA, a small maker of fashionable notebooks, is another example of imitation strategy but in a different way: looking to open more retail shops around the world, it imitates the expansion strategies of larger, successful fashion companies Salvatore Ferragamo SpA and Brunello Cucinelli.37

Structural Matches

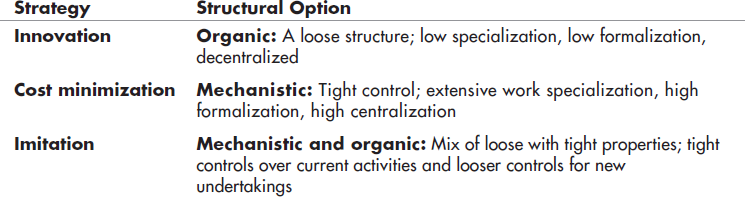

Exhibit 15-7 describes the structural option that best matches each strategy. Innovators need the flexibility of the organic structure (although, as we noted, they may use some elements of the mechanistic structure as well), whereas cost minimizers seek the efficiency and stability of the mechanistic structure. Imitators combine the two structures. They use a mechanistic structure to maintain tight controls and low costs in their current activities but create organic subunits in which to pursue new opportunities.

Exhibit 15-7

The Optimal Structural Option for Each Organizational Strategy

Organization Size

An organization’s size significantly affects its structure. Organizations that employ 2,000 or more people tend to have more specialization, more departmentalization, more vertical levels, and more rules and regulations than do small organizations. However, size becomes less important as an organization expands. Why? At around 2,000 employees, an organization is already fairly mechanistic; 500 more employees won’t have much impact. But adding 500 employees to an organization of only 300 is likely to significantly shift it toward a more mechanistic structure.

Technology

![]() Technology describes the way an organization transfers inputs into outputs. Every organization has at least one technology for converting financial, human, and physical resources into products or services. For example, the Chinese consumer electronics company Haier uses an assembly-line process for mass-produced products, which is complemented by more flexible and innovative structures to respond to customers and design new products.38 Also, colleges may use a number of instructional technologies—the ever-popular lecture, case analysis, experiential exercise, programmed learning, online instruction, and distance learning. Regardless, organizational structures adapt to their technology.

Technology describes the way an organization transfers inputs into outputs. Every organization has at least one technology for converting financial, human, and physical resources into products or services. For example, the Chinese consumer electronics company Haier uses an assembly-line process for mass-produced products, which is complemented by more flexible and innovative structures to respond to customers and design new products.38 Also, colleges may use a number of instructional technologies—the ever-popular lecture, case analysis, experiential exercise, programmed learning, online instruction, and distance learning. Regardless, organizational structures adapt to their technology.

Environment

An organization’s environment includes outside institutions or forces that can affect its structure, such as suppliers, customers, competitors, and public pressure groups. Dynamic environments create significantly more uncertainty for managers than do static ones. To minimize uncertainty in key market arenas, managers may broaden their structure to sense and respond to threats. Most companies, for example Pepsi and Southwest Airlines, have added social networking departments to counter negative information posted on blogs. Or companies may form strategic alliances.

Any organization’s environment has three dimensions: capacity, volatility, and complexity.39 Let’s discuss each separately.

Capacity

Capacity refers to the degree to which the environment can support growth. Rich and growing environments generate excess resources, which can buffer the organization in times of relative scarcity.

Volatility

Volatility describes the degree of instability in the environment. A dynamic environment with a high degree of unpredictable change makes it difficult for management to make accurate predictions. Because information technology changes at such a rapid place, more organizations’ environments are becoming volatile.

Complexity

Finally, complexity is the degree of heterogeneity and concentration among environmental elements. Simple environments—like the tobacco industry where the methods of production, competitive and regulatory pressures, and the like haven’t changed in quite some time—are homogeneous and concentrated. Environments characterized by heterogeneity and dispersion—like the broadband industry—are complex and diverse, with numerous competitors.

Three-Dimensional Model

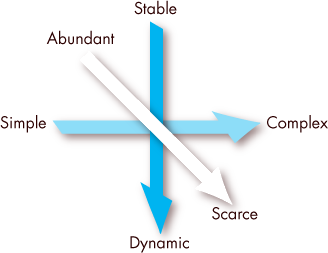

Exhibit 15-8 summarizes our definition of the environment along its three dimensions. The arrows indicate movement toward higher uncertainty. Thus, organizations that operate in environments characterized as scarce, dynamic, and complex face the greatest degree of uncertainty because they have high unpredictability, little room for error, and a diverse set of elements in the environment to monitor constantly.

Exhibit 15-8

The Environment Along Three Dimensions

Given this three-dimensional definition of environment, we can offer some general conclusions about environmental uncertainty and structural arrangements. The more scarce, dynamic, and complex the environment, the more organic a structure should be. The more abundant, stable, and simple the environment, the more the mechanistic structure will be preferred.

Institutions

Another factor that shapes organizational structure is institutions. These are cultural factors that act as guidelines for appropriate behavior.40 Institutional theory describes some of the forces that lead many organizations to have similar structures and, unlike the theories we’ve described so far, focuses on pressures that aren’t necessarily adaptive. In fact, many institutional theorists try to highlight the ways corporate behaviors sometimes seem to be performance oriented but are actually guided by unquestioned social norms and conformity.

The most obvious institutional factors come from regulatory pressures; certain industries under government contracts, for instance, must have clear reporting relationships and strict information controls. Sometimes simple inertia determines an organizational form—companies can be structured in a particular way just because that’s the way things have always been done. Organizations in countries with high power distance might have a structural form with strict authority relationships because it’s seen as more legitimate in that culture. Some have attributed problems in adaptability in Japanese organizations to the institutional pressure to maintain authority relationships.

Sometimes organizations start to have a particular structure because of fads or trends. Organizations can try to copy other successful companies just to look good to investors, and not because they need that structure to perform better. Many companies have recently tried to copy the organic form of a company like Google only to find that such structures are a very poor fit with their operating environment. Institutional pressures are often difficult to see specifically because we take them for granted, but that doesn’t mean they aren’t powerful.