What are Emotions and Moods?

In our analysis of the role of emotions and moods in the workplace, we need three terms that are closely intertwined: affect, emotions, and moods. Affect is a generic term that covers a broad range of feelings, including both emotions and moods.1 Emotions are intense feelings directed at someone or something.2 Moods are less intense feelings than emotions and often arise without a specific event acting as a stimulus.3 Exhibit 4-1 shows the relationships among affect, emotions, and moods.

Exhibit 4-1

Affect, Emotions, and Moods

First, as the exhibit shows, affect is a broad term that encompasses emotions and moods. Second, there are differences between emotions and moods. Emotions are more likely to be caused by a specific event and are more fleeting than moods. Also, some researchers speculate that emotions may be more action-oriented—they may lead us to some immediate action—while moods may be more cognitive, meaning they may cause us to think or brood for a while.4

Affect, emotions, and moods are separable in theory; in practice, the distinction isn’t always defined. When we review the OB topics on emotions and moods, you may see more information about emotions in one area and more about moods in another. This is simply the state of the research. Let’s start with a review of the basic emotions.

The Basic Emotions

How many emotions are there? There are dozens, including anger, contempt, enthusiasm, envy, fear, frustration, disappointment, embarrassment, disgust, happiness, hate, hope, jealousy, joy, love, pride, surprise, and sadness. Numerous researchers have tried to limit them to a fundamental set.5 Other scholars argue that it makes no sense to think in terms of “basic” emotions, because even emotions we rarely experience, such as shock, can have a powerful effect on us.6 It’s unlikely psychologists or philosophers will ever completely agree on a set of basic emotions, or even on whether there is such a thing. Still, many researchers agree on six universal emotions—anger, fear, sadness, happiness, disgust, and surprise. We sometimes mistake happiness for surprise, but rarely do we confuse happiness and disgust.

![]() Psychologists have tried to identify basic emotions by studying how we express them. Of our myriad ways of expressing emotions, facial expressions have proved one of the most difficult to interpret.7 One problem is that some emotions are too complex to be easily represented on our faces. Second, people may not interpret emotions from vocalizations (such as sighs or screams) the same way across cultures. One study found that while vocalizations conveyed meaning in all cultures, the specific emotions people perceived varied. For example, Himba participants (from northwestern Namibia) did not agree with Western participants that crying meant sadness or a growl meant anger.8 Lastly, cultures have norms that govern emotional expression, so the way we experience an emotion isn’t always the same as the way we show it. For example, people in the Middle East and the United States recognize a smile as indicating happiness, but in the Middle East, a smile is also often interpreted as a sign of sexual attraction, so women have learned not to smile at men.

Psychologists have tried to identify basic emotions by studying how we express them. Of our myriad ways of expressing emotions, facial expressions have proved one of the most difficult to interpret.7 One problem is that some emotions are too complex to be easily represented on our faces. Second, people may not interpret emotions from vocalizations (such as sighs or screams) the same way across cultures. One study found that while vocalizations conveyed meaning in all cultures, the specific emotions people perceived varied. For example, Himba participants (from northwestern Namibia) did not agree with Western participants that crying meant sadness or a growl meant anger.8 Lastly, cultures have norms that govern emotional expression, so the way we experience an emotion isn’t always the same as the way we show it. For example, people in the Middle East and the United States recognize a smile as indicating happiness, but in the Middle East, a smile is also often interpreted as a sign of sexual attraction, so women have learned not to smile at men.

![]() Cultural differences regarding emotions can be apparent between countries that are individualistic and collectivistic—broad terms that describe the general outlook of people in a society. Individualistic countries are those in which people see themselves as independent and desire personal goals and personal control. Individualistic values are present in North America and Western Europe, for example. Collectivistic countries are those in which people see themselves as interdependent and seek community and group goals. Collectivistic values are found in Asia, Africa, and South America, for example.9 For this application, we find that in collectivist countries, people are more likely to believe another’s emotional displays are connected to their personal relationship, while people in individualistic cultures don’t think others’ emotional expressions are directed at them.

Cultural differences regarding emotions can be apparent between countries that are individualistic and collectivistic—broad terms that describe the general outlook of people in a society. Individualistic countries are those in which people see themselves as independent and desire personal goals and personal control. Individualistic values are present in North America and Western Europe, for example. Collectivistic countries are those in which people see themselves as interdependent and seek community and group goals. Collectivistic values are found in Asia, Africa, and South America, for example.9 For this application, we find that in collectivist countries, people are more likely to believe another’s emotional displays are connected to their personal relationship, while people in individualistic cultures don’t think others’ emotional expressions are directed at them.

Moral Emotions

Researchers have been studying what are called moral emotions; that is, emotions that have moral implications because of our instant judgment of the situation that evokes them. Examples of moral emotions include sympathy for the suffering of others, guilt about our own immoral behavior, anger about injustice done to others, and contempt for those who behave unethically.

Another example is the disgust we feel about violations of moral norms, called moral disgust. Moral disgust is different from disgust. Say you stepped in cow dung by mistake—you might feel disgusted by it, but not moral disgust—you probably wouldn’t make a moral judgment. In contrast, say you watched a video of a police officer making a sexist or racist slur. You might feel disgusted in a different way because it offends your sense of right and wrong. In fact, you might feel a variety of emotions based on your moral judgment of the situation.10

The Basic Moods: Positive and Negative Affect

Emotions can be fleeting, but moods can endure... for quite a while. As a first step toward studying the effect of moods and emotions in the workplace, we classify emotions into two categories: positive and negative. Positive emotions—such as joy and gratitude—express a favorable evaluation or feeling. Negative emotions—such as anger and guilt—express the opposite. Keep in mind that emotions can’t be neutral. Being neutral is being nonemotional.11

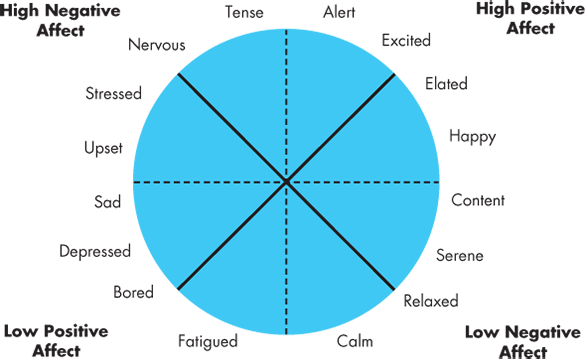

The two categories of emotions represent overall mood states, known as positive and negative affect (see Exhibit 4-2). We can think of positive affect as a mood dimension consisting of positive emotions such as excitement, enthusiasm, and elation at the high end (high positive affect) and boredom, depression, and fatigue at the low end (low positive affect, or lack of positive affect). Negative affect is a mood dimension consisting of nervousness, stress, and anxiety at the high end (high negative affect) and contentedness, calmness, and serenity at the low end (low negative affect, or lack of negative affect). While we rarely experience both positive and negative affect at the same time, over time people do differ in how much they experience of each. Some people (we might call them emotional or intense) may experience quite a bit of high positive and high negative affect over, say, a week’s time. Others (we might call them unemotional or phlegmatic) experience little of either. And still others may experience one much more predominately than the other.

Exhibit 4-2

The Affective Circumplex

Experiencing Moods and Emotions

![]() As if it weren’t complex enough to consider the many distinct emotions and moods a person might identify, the reality is that we each experience moods and emotions differently. For most people, positive moods are somewhat more common than negative moods. Indeed, research finds a positivity offset, meaning that at zero input (when nothing in particular is going on), most individuals experience a mildly positive mood.12 This appears to be true for employees in a wide range of job settings. For example, one study of customer-service representatives in a British call center revealed that people reported experiencing positive moods 58 percent of the time, despite the stressful environment.13 Another research finding is that negative emotions lead to negative moods.

As if it weren’t complex enough to consider the many distinct emotions and moods a person might identify, the reality is that we each experience moods and emotions differently. For most people, positive moods are somewhat more common than negative moods. Indeed, research finds a positivity offset, meaning that at zero input (when nothing in particular is going on), most individuals experience a mildly positive mood.12 This appears to be true for employees in a wide range of job settings. For example, one study of customer-service representatives in a British call center revealed that people reported experiencing positive moods 58 percent of the time, despite the stressful environment.13 Another research finding is that negative emotions lead to negative moods.

![]() There is much to be learned in exploring cultural differences. Some cultures embrace negative emotions, such as Japan and Russia, while others emphasize positive emotions and expressions, such as Mexico and Brazil.14 There may also be a difference in the value of negative emotions between collectivist and individualist countries, and this difference may be the reason negative emotions are less detrimental to the health of Japanese than Americans.15 For example, the Chinese consider negative emotions—while not always pleasant—as potentially more useful and constructive than do Americans.

There is much to be learned in exploring cultural differences. Some cultures embrace negative emotions, such as Japan and Russia, while others emphasize positive emotions and expressions, such as Mexico and Brazil.14 There may also be a difference in the value of negative emotions between collectivist and individualist countries, and this difference may be the reason negative emotions are less detrimental to the health of Japanese than Americans.15 For example, the Chinese consider negative emotions—while not always pleasant—as potentially more useful and constructive than do Americans.

The Function of Emotions

Emotions may be a mystery, but they can be critical to an effectively functioning workplace. For example, employees with more positive emotions demonstrate higher performance and organizational citizenship behavior (OCB; see Chapter 1), less turnover and counterproductive work behavior (CWB; see Chapter 3), particularly when they feel supported by their organizations in their effort to do well in their jobs.16 Gratefulness and awe have also been shown to positively predict OCB,17 which in turn increases trust and emotional expressions of concern.18 Let’s discuss two critical areas—rationality and ethicality—in which emotions can enhance performance.

Do Emotions Make Us Irrational?

How often have you heard someone say, “Oh, you’re just being emotional?” You might have been offended. Observations like this suggest that rationality and emotion are in conflict, and by exhibiting emotion, you are acting irrationally. The perceived association between the two is so strong that some researchers argue displaying emotions such as sadness to the point of crying is so toxic to a career that we should leave the room rather than allow others to witness it.19 This perspective suggests the demonstration or even experience of emotions can make us seem weak, brittle, or irrational. However, this is wrong.

Research increasingly indicates that emotions are critical to rational thinking. Brain injury studies in particular suggest we must have the ability to experience emotions to be rational. Why? Because our emotions provide a context for how we understand the world around us. For instance, a recent study indicated that individuals in a negative mood are better able to discern truthful information than people in a happy mood.20 Therefore, if we have a concern about someone telling the truth, shouldn’t we conduct an inquiry while we are actively concerned, rather than wait until we cheer up? There may be benefits to this, or maybe not, depending on all the factors including the range of our emotions. The keys are to acknowledge the effect that emotions and moods are having on us, and to not discount our emotional responses as irrational or invalid.

Do Emotions Make Us Ethical?

A growing body of research has begun to examine the relationship between emotions and moral attitudes.21 It was previously believed that, like decision making in general, most ethical decision making was based on higher-order cognitive processes, but the research on moral emotions increasingly questions this perspective. Numerous studies suggest that moral judgments are largely based on feelings rather than on cognition, even though we tend to see our moral boundaries as logical and reasonable, not as emotional.

To some degree, our beliefs are shaped by our peer, interest, and work groups which influence our perceptions of others, resulting in unconscious responses and a feeling that our shared emotions are “right.” Unfortunately, this feeling sometimes allows us to justify purely emotional reactions as rationally “ethical.”22 We also tend to judge out-group members (anyone who is not in our group) more harshly for moral transgressions than in-group members, even when we are trying to be objective.23 In addition, perhaps to restore an emotional sense of fair play, we are likely to spitefully want outgroup members to be punished.24