The Conflict Process

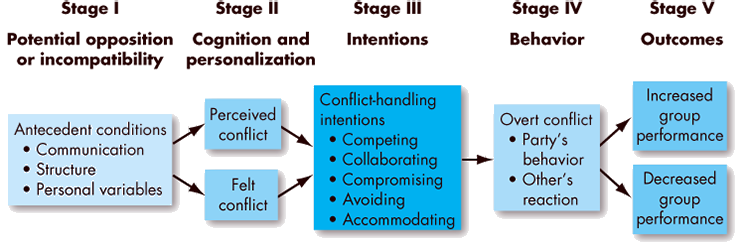

The conflict process has five stages: potential opposition or incompatibility, cognition and personalization, intentions, behavior, and outcomes (see Exhibit 14-2).

Exhibit 14-2

The Conflict Process

Stage I: Potential Opposition or Incompatibility

The first stage of conflict is the appearance of conditions—causes or sources—that create opportunities for it to arise. These conditions need not lead directly to conflict, but one of them is necessary if it is to surface. We group the conditions into three general categories: communication, structure, and personal variables.

Communication

Communication can be a source of conflict.6 There are opposing forces that arise from semantic difficulties, misunderstandings, and “noise” in the communication channel (see Chapter 11). These factors, along with jargon and insufficient information, can be barriers to communication and potential antecedent conditions to conflict. The potential for conflict has also been found to increase with too little or too much communication. Communication is functional up to a point, after which it is possible to overcommunicate, increasing the potential for conflict.

Structure

The term structure in this context includes variables such as size of group, degree of specialization in tasks assigned to group members, jurisdictional clarity, member–goal compatibility, leadership styles, reward systems, and degree of dependence between groups. The larger the group and the more specialized its activities, the greater the likelihood of conflict. Tenure and conflict are inversely related, meaning that the longer a person stays with an organization, the less likely conflict becomes. Therefore, the potential for conflict is greatest when group members are newer to the organization and when turnover is high.

Personal Variables

![]() Our last category of potential sources of conflict is personal variables, which include personality, emotions, and values. People high in the personality traits of disagreeableness, neuroticism, or self-monitoring (see Chapter 5) are prone to tangle with other people more often—and to react poorly when conflicts occur.7 Emotions can cause conflict even when they are not directed at others. For example, an employee who shows up to work irate from her hectic morning commute may carry that anger into her workday, which can result in a tension-filled meeting.8 Furthermore, differences in preferences and values can generate increased levels of conflict. For example, a study in Korea found that when group members didn’t agree about their desired achievement levels, there was more task conflict; when group members didn’t agree about their desired interpersonal closeness levels, there was more relationship conflict; and when group members didn’t have similar desires for power, there was more conflict over status.9

Our last category of potential sources of conflict is personal variables, which include personality, emotions, and values. People high in the personality traits of disagreeableness, neuroticism, or self-monitoring (see Chapter 5) are prone to tangle with other people more often—and to react poorly when conflicts occur.7 Emotions can cause conflict even when they are not directed at others. For example, an employee who shows up to work irate from her hectic morning commute may carry that anger into her workday, which can result in a tension-filled meeting.8 Furthermore, differences in preferences and values can generate increased levels of conflict. For example, a study in Korea found that when group members didn’t agree about their desired achievement levels, there was more task conflict; when group members didn’t agree about their desired interpersonal closeness levels, there was more relationship conflict; and when group members didn’t have similar desires for power, there was more conflict over status.9

Stage II: Cognition and Personalization

If the conditions cited in Stage I negatively affect something one party cares about, then the potential for opposition or incompatibility becomes actualized in the second stage.

As we noted in our definition of conflict, one or more of the parties must be aware that antecedent conditions exist. However, just because a disagreement is a perceived conflict does not mean it is personalized. It is at the felt conflict level, when individuals become emotionally involved, that they experience anxiety, tension, frustration, or hostility.

Stage II is important because it’s where conflict issues tend to be defined, where the parties decide what the conflict is about.10 The definition of conflict is important because it delineates the set of possible settlements. Most evidence suggests that people tend to default to cooperative strategies in interpersonal interactions unless there is a clear signal that they are faced with a competitive person. However, if our disagreement regarding, say, your salary is a zero-sum situation (the increase in pay you want means there will be that much less in the raise pool for me), I am going to be far less willing to compromise than if I can frame the conflict as a potential win–win situation (the dollars in the salary pool might be increased so both of us could get the added pay we want).

Second, emotions play a major role in shaping perceptions.11 Negative emotions allow us to oversimplify issues, lose trust, and put negative interpretations on the other party’s behavior.12 In contrast, positive feelings increase our tendency to see potential relationships among elements of a problem, take a broader view of the situation, and develop innovative solutions.13

Stage III: Intentions

Intentions intervene between people’s perceptions and emotions, and their overt behavior. They are decisions to act in a given way.14 There is slippage between intentions and behavior, so behavior does not always accurately reflect a person’s intentions.

Using two dimensions—assertiveness (the degree to which one party attempts to satisfy his or her own concerns) and cooperativeness (the degree to which one party attempts to satisfy the other party’s concerns)—we can identify five conflict-handling intentions: competing (assertive and uncooperative), collaborating (assertive and cooperative), avoiding (unassertive and uncooperative), accommodating (unassertive and cooperative), and compromising (mid-range on both assertiveness and cooperativeness).15

Intentions are not always fixed. During the course of a conflict, intentions might change if a party is able to see the other’s point of view or to respond emotionally to the other’s behavior. People generally have preferences among the five conflict-handling intentions. We can predict a person’s intentions rather well from a combination of intellectual and personality characteristics.

Competing

When one person seeks to satisfy his or her own interests regardless of the impact on the other parties in the conflict, that person is competing. We are more apt to compete when resources are scarce.

Collaborating

When parties in conflict each desire to fully satisfy the concerns of all parties, there is cooperation and a search for a mutually beneficial outcome. In collaborating, parties intend to solve a problem by clarifying differences rather than by accommodating various points of view. If you attempt to find a win–win solution that allows both parties’ goals to be completely achieved, that’s collaborating.

Avoiding

A person may recognize a conflict exists and want to withdraw from or suppress it. Examples of avoiding include trying to ignore a conflict and keeping away from others with whom you disagree.

Accommodating

A party who seeks to appease an opponent may be willing to place the opponent’s interests above his or her own, sacrificing to maintain the relationship. We refer to this intention as accommodating. Supporting someone else’s opinion despite your reservations about it, for example, is accommodating.

Compromising

In compromising, there is no winner or loser. Rather, there is a willingness to ration the object of the conflict and accept a solution with incomplete satisfaction of both parties’ concerns. The distinguishing characteristic of compromising, therefore, is that each party intends to give up something.

A review that examined the effects of the four sets of behaviors across multiple studies found that openness and collaborating were both associated with superior group performance, whereas avoiding and competing strategies were associated with significantly worse group performance.16 These effects were nearly as large as the effects of relationship conflict. This further demonstrates that it is not just the existence of conflict or even the type of conflict that creates problems, but rather the ways people respond to conflict and manage the process once conflicts arise.

Stage IV: Behavior

Stage IV is a dynamic process of interaction. For example, you make a demand on me, I respond by arguing, you threaten me, I threaten you back, and so on. Exhibit 14-3 provides a way of visualizing conflict behavior. Each behavioral stage in a conflict is built upon a foundation. At the lowest point are perceptions, misunderstandings, and differences of opinions. These may grow to subtle, indirect, and highly controlled forms of tension, such as a student challenging a point the instructor has made. Conflict can intensify until it becomes highly destructive. Strikes, riots, and wars clearly fall in this upper range. Conflicts that reach the upper ranges of the continuum are almost always dysfunctional. Functional conflicts are typically confined to the lower levels.

Exhibit 14-3

Dynamic Escalation of Conflict

Sources: P. T. Coleman, R. R. Vallacher, A. Nowak, and L. Bui-Wrzosinska, “Intractable Conflict as an Attractor: A Dynamical Systems Approach to Conflict Escalation and Intractability,” The American Behavioral Scientist 50, no. 11 (2007): 1545–75; K. K. Petersen, “Conflict Escalation in Dyads with a History of Territorial Disputes,” International Journal of Conflict Management 21, no. 4 (2010): 415–33.

In conflict, intentions are translated into certain likely behaviors. Competing brings out active attempts to contend with team members, and greater individual effort to achieve ends without working together. Collaborating efforts create an investigation of multiple solutions with other members of the team and trying to find a solution that satisfies all parties as much as possible. Avoidance is seen in behavior like refusals to discuss issues and reductions in effort toward group goals. People who accommodate put their relationships ahead of the issues in the conflict, deferring to others’ opinions and sometimes acting as a subgroup with them. Finally, when people compromise, they both expect to (and do) sacrifice parts of their interests, hoping that if everyone does the same, an agreement will sift out.

If a conflict is dysfunctional, what can the parties do to de-escalate it? Or, conversely, what options exist if conflict is too low to be functional and needs to be increased? This brings us to techniques of conflict management. We have already described several techniques in terms of conflict-handling intentions. Under ideal conditions, a person’s intentions should translate into comparable behaviors.

Stage V: Outcomes

The action–reaction interplay between conflicting parties creates consequences. As our model demonstrates (see Exhibit 14-1), these outcomes may be functional if the conflict improves the group’s performance, or dysfunctional if it hinders performance.

Functional Outcomes

Conflict is constructive when it improves the quality of decisions, stimulates creativity and innovation, encourages interest and curiosity among group members, provides the medium for problems to be aired and tensions released, and fosters self-evaluation and change. Mild conflicts also may generate energizing emotions so members of groups become more active and engaged in their work.17

Conflict is an antidote for groupthink (see Chapter 9). Conflict doesn’t allow the group to passively rubber-stamp decisions that may be based on weak assumptions, inadequate consideration of relevant alternatives, or other debilities. Conflict challenges the status quo and furthers the creation of new ideas, promotes reassessment of group goals and activities, and increases the probability that the group will respond to change. An open discussion focused on higher-order goals can make functional outcomes more likely. Groups that are extremely polarized do not manage their underlying disagreements effectively and tend to accept suboptimal solutions, or they avoid making decisions altogether rather than work out the conflict.18 Research studies in diverse settings confirm the functionality of active discussion. Team members with greater differences in work styles and experience tend to share more information with one another.19

Dysfunctional Outcomes

The destructive consequences of conflict on the performance of a group or an organization are generally well known: Uncontrolled opposition breeds discontent, which acts to dissolve common ties and eventually leads to the destruction of the group. A substantial body of literature documents how dysfunctional conflicts can reduce group effectiveness.20 Among the undesirable consequences are poor communication, reductions in group cohesiveness, and subordination of group goals to the primacy of infighting among members. All forms of conflict—even the functional varieties—appear to reduce group member satisfaction and trust.21 When active discussions turn into open conflicts between members, information sharing between members decreases significantly.22 At the extreme, conflict can bring group functioning to a halt and threaten the group’s survival.

Managing Conflict

One of the keys to minimizing counterproductive conflicts is recognizing when there really is a disagreement. Many apparent conflicts are due to people using different verbiage to discuss the same general course of action. For example, someone in marketing might focus on “distribution problems,” while someone from operations talks about “supply chain management” to describe essentially the same issue. Successful conflict management recognizes these different approaches and attempts to resolve them by encouraging open, frank discussions focused on interests rather than issues. Another approach is to have opposing groups pick parts of the solution that are most important to them and then focus on how each side can get its top needs satisfied. Neither side may get exactly what it wants, but each side will achieve the most important parts of its agenda.23 Third, groups that resolve conflicts successfully discuss differences of opinion openly and are prepared to manage conflict when it arises.24 An open discussion makes it much easier to develop a shared perception of the problems at hand; it also allows groups to work toward a mutually acceptable solution. Fourth, managers need to emphasize shared interests in resolving conflicts, so groups that disagree with one another don’t become too entrenched in their points of view and start to take the conflicts personally. Groups with cooperative conflict styles and a strong underlying identification with the overall group goals are more effective than groups with a competitive style.25

Cultural Influences

![]() Differences across countries in conflict resolution strategies may be based on collectivistic versus individualistic (see Chapter 4) tendencies and motives. Collectivistic cultures see people as deeply embedded in social situations, whereas individualistic cultures see them as autonomous. As a result, collectivists are more likely to seek to preserve relationships and promote the good of the group as a whole, and they prefer indirect methods for resolving differences of opinion. One study suggests that top management teams in Chinese high-technology firms prefer collaboration even more than compromising and avoiding. Collectivists may also be more interested in demonstrations of concern and working through third parties to resolve disputes, whereas individualists will be more likely to confront differences of opinion directly and openly.

Differences across countries in conflict resolution strategies may be based on collectivistic versus individualistic (see Chapter 4) tendencies and motives. Collectivistic cultures see people as deeply embedded in social situations, whereas individualistic cultures see them as autonomous. As a result, collectivists are more likely to seek to preserve relationships and promote the good of the group as a whole, and they prefer indirect methods for resolving differences of opinion. One study suggests that top management teams in Chinese high-technology firms prefer collaboration even more than compromising and avoiding. Collectivists may also be more interested in demonstrations of concern and working through third parties to resolve disputes, whereas individualists will be more likely to confront differences of opinion directly and openly.

Cross-cultural negotiations can create issues of trust.26 One study of Indian and U.S. negotiators found that respondents reported having less trust in their cross-culture negotiation counterparts. The lower level of trust was associated with less discovery of common interests between parties, which occurred because cross-culture negotiators were less willing to disclose and solicit information. Another study found that both U.S. and Chinese negotiators tended to have an ingroup bias, which led them to favor negotiating partners from their own cultures. For Chinese negotiators, this was particularly true when accountability requirements were high.

![]() Having considered conflict—its nature, causes, and consequences—we now turn to negotiation, which often resolves conflict.

Having considered conflict—its nature, causes, and consequences—we now turn to negotiation, which often resolves conflict.

Watch It

Watch It

If your professor has assigned this, go to the Assignments section of mymanagementlab.com to complete the video exercise titled Gordon Law Group: Conflict and Negotiation.