Contemporary Theories of Motivation

Contemporary theories of motivation have one thing in common: Each has a reasonable degree of valid supporting documentation. We call them “contemporary theories” because they represent the latest thinking in explaining employee motivation. This doesn’t mean they are unquestionably right.

Self-Determination Theory

“It’s strange,” said Marcia. “I started work at the Humane Society as a volunteer. I put in 15 hours a week helping people adopt pets. And I loved coming to work. Then, three months ago, they hired me full-time at $11 an hour. I’m doing the same work I did before. But I’m not finding it as much fun.”

Does Marcia’s reaction seem counterintuitive? There’s an explanation for it. It’s called self-determination theory, which proposes that people prefer to feel they have control over their actions, so anything that makes a previously enjoyed task feel more like an obligation than a freely chosen activity will undermine motivation.16 The theory is widely used in psychology, management, education, and medical research, and has given rise to several corollaries including organizational evaluation theory and self-concordance theory, discussed next.

Cognitive Evaluation Theory

Much research on self-determination theory in OB has focused on cognitive evaluation theory, a complementary theory hypothesizing that extrinsic rewards will reduce intrinsic interest in a task. When people are paid for work, it feels less like something they want to do and more like something they have to do. Self-determination theory proposes that in addition to being driven by a need for autonomy, people seek ways to achieve competence and make positive connections with others. Its major implications relate to work rewards.

What does self-determination theory suggest about providing rewards? It suggests that some caution in the use of extrinsic rewards to motivate is wise, and that pursuing goals from intrinsic motives (such as a strong interest in the work itself) is more sustaining to human motivation than are extrinsic rewards. Similarly, cognitive evaluation theory suggests that providing extrinsic incentives may, in many cases, undermine intrinsic motivation. For example, if a computer programmer values writing code because she likes to solve problems, a bonus for writing a certain number of lines of code every day could feel coercive, and her intrinsic motivation could suffer. She may or may not increase her number of lines of code per day in response to the extrinsic motivator. In support of the theory, one meta-analysis confirmed that intrinsic motivation contributes to the quality of work, while incentives contribute to the quantity of work. Although intrinsic motivation predicts performance whether or not there are incentives, it may therefore be less of a predictor when incentives are tied to performance directly (such as with monetary bonuses) rather than indirectly.17

Self-Concordance

![]() A more recent outgrowth of self-determination theory is self-concordance, which considers how strongly people’s reasons for pursuing goals are consistent with their interests and core values. OB research suggests that people who pursue work goals for intrinsic reasons are more satisfied with their jobs, feel they fit into their organizations better, and perform better.18 Across cultures, if individuals pursue goals because of intrinsic interest, they are more likely to attain goals, are happier when they do, and are happy even if they do not.19 Why? Because the process of striving toward goals is fun whether or not the goal is achieved. Recent research reveals that when people do not enjoy their work for intrinsic reasons, those who work because they feel obligated to do so can still perform acceptably, though they experience higher levels of strain as a result.20

A more recent outgrowth of self-determination theory is self-concordance, which considers how strongly people’s reasons for pursuing goals are consistent with their interests and core values. OB research suggests that people who pursue work goals for intrinsic reasons are more satisfied with their jobs, feel they fit into their organizations better, and perform better.18 Across cultures, if individuals pursue goals because of intrinsic interest, they are more likely to attain goals, are happier when they do, and are happy even if they do not.19 Why? Because the process of striving toward goals is fun whether or not the goal is achieved. Recent research reveals that when people do not enjoy their work for intrinsic reasons, those who work because they feel obligated to do so can still perform acceptably, though they experience higher levels of strain as a result.20

What does all this mean? For individuals, it means you should choose your job for reasons other than extrinsic rewards. For organizations, it means managers should provide intrinsic as well as extrinsic incentives. Managers need to make the work interesting, provide recognition, and support employee growth and development. Employees who feel that what they do is within their control and a result of free choice are likely to be more motivated by their work and committed to their employers.21

Goal-Setting Theory

You’ve likely heard the sentiment a number of times: “Just do your best. That’s all anyone can ask.” But what does “do your best” mean? Do we ever know whether we’ve achieved that vague goal? Research on goal-setting theory, proposed by Edwin Locke, reveals the impressive effects of goal specificity, challenge, and feedback on performance. Under the theory, intentions to work toward a goal are considered a major source of work motivation.22

Difficulty and Feedback Dimensions

Goal-setting theory is well supported. First, evidence strongly suggests that specific goals increase performance; that difficult goals, when accepted, produce higher performances than do easy goals; and that feedback leads to higher performance than does non-feedback.23 Second, the more difficult the goal is, the higher the level of performance. Once a hard task has been accepted, we can expect the employee to exert a high level of effort to try to achieve it. Third, people do better when they get feedback on how well they are progressing toward their goals—that is, feedback guides behavior. But all feedback is not equally potent. Self-generated feedback—with which employees are able to monitor their own progress or receive feedback from the task process itself—is more powerful than externally generated feedback.24

![]() If employees can participate in the setting of their own goals, will they try harder? The evidence is mixed. In some studies, participatively set goals yielded superior performance; in others, individuals performed best when assigned goals by their boss. One study in China found, for instance, that participative team goal setting improved team outcomes.25 Another study found that participation results in more achievable goals for individuals.26 Without participation, the individual pursuing the goal needs to clearly understand its purpose and importance.27

If employees can participate in the setting of their own goals, will they try harder? The evidence is mixed. In some studies, participatively set goals yielded superior performance; in others, individuals performed best when assigned goals by their boss. One study in China found, for instance, that participative team goal setting improved team outcomes.25 Another study found that participation results in more achievable goals for individuals.26 Without participation, the individual pursuing the goal needs to clearly understand its purpose and importance.27

Goal Commitment, Task Characteristics, and National Culture Factors

Three personal factors influence the goals–performance relationship: goal commitment, task characteristics, and national culture.

Goal commitment. Goal-setting theory assumes an individual is committed to the goal and determined not to lower or abandon it. The individual (1) believes he or she can achieve the goal and (2) wants to achieve it.28 Goal commitment is most likely to occur when goals are made public, when the individual has an internal locus of control, when the goals are self-set rather than assigned, and when they are based at least partially on individual ability.29

Task characteristics. Goals themselves seem to affect performance more strongly when tasks are simple rather than complex, well learned rather than novel, independent rather than interdependent, and on the high end of achievable.30 On interdependent tasks, group goals are more effective.

National characteristics. Goals may have different effects in different cultures. In collectivistic and high power-distance cultures, achievable moderate goals can be more motivating than difficult ones.31 However, research has not shown group-based goals to be effective in collectivist than in individualist cultures (see Chapter 4). More research is needed to assess how goal constructs might differ across cultures.

Individual and Promotion Foci

Research has found that people differ in the way they regulate their thoughts and behaviors during goal pursuit. Generally, people fall into one of two categories, though they can belong to both. Those with a promotion focus strive for advancement and accomplishment, and approach conditions that move them closer toward desired goals. This concept is similar to the approach side of the approach-avoidance framework discussed in Chapter 5. Those with a prevention focus strive to fulfill duties and obligations, as well as avoid conditions, that pull them away from desired goals. Aspects of this concept are similar to the avoidance side of the approach-avoidance framework. Although you would be right to note that both strategies are in the service of goal accomplishment, the manner in which they get there is quite different. As an example, consider studying for an exam. You could engage in promotion-focused activities such as reading class materials, or you could engage in prevention-focused activities such as refraining from doing things that would get in the way of studying, such as playing video games.

Ideally, it’s probably best to be both promotion and prevention oriented.32 Keep in mind a person’s job satisfaction will be more heavily impacted by failure when that person has an avoidance (prevention) outlook,33 so set achievable goals, remove distractions, and provide structure to reduce the potential for missing a goal.34

Goal-Setting Implementation

How do managers make goal-setting theory operational? That’s often left up to the individual. Some managers set aggressive performance targets—what General Electric called “stretch goals.” Some leaders, such as U.S. Secretary of Veterans Affairs (and former Procter & Gamble CEO) Robert McDonald and Best Buy’s CEO Hubert Joly, are known for their demanding performance goals. But many managers don’t set goals. When asked whether their jobs had clearly defined goals, a minority of respondents to a survey said yes.35

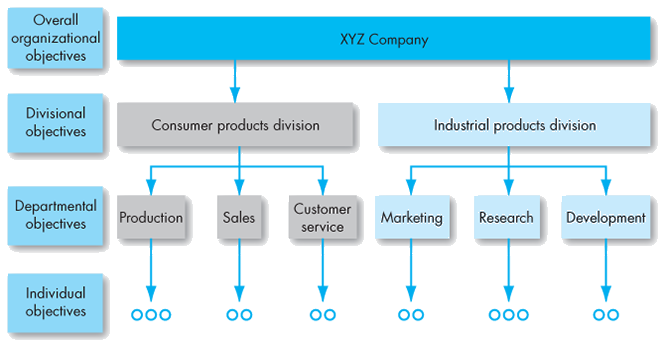

A more systematic way to utilize goal setting is with management by objectives (MBO), an initiative most popular in the 1970s but still used today. MBO emphasizes participatively set goals that are tangible, verifiable, and measurable. As in Exhibit 7-3, the organization’s overall objectives are translated into specific cascading objectives for each level (divisional, departmental, individual). Because lower-unit managers jointly participate in setting their own goals, MBO works from the bottom up as well as from the top down. The result is a hierarchy that links objectives at one level to those at the next. For the individual employee, MBO provides specific personal performance objectives.

Exhibit 7-3

Cascading of Objectives

![]() Many elements in MBO programs match the propositions of goal-setting theory. You’ll find MBO programs in many business, health care, educational, government, and nonprofit organizations.36 A version of MBO, called Management by Objectives and Results (MBOR), has been used for over 30 years in the governments of Denmark, Norway, and Sweden.37 However, the popularity of these programs does not mean they always work.38 When MBO fails, the culprits tend to be unrealistic expectations, lack of commitment by top management, and inability or unwillingness to allocate rewards based on goal accomplishment.

Many elements in MBO programs match the propositions of goal-setting theory. You’ll find MBO programs in many business, health care, educational, government, and nonprofit organizations.36 A version of MBO, called Management by Objectives and Results (MBOR), has been used for over 30 years in the governments of Denmark, Norway, and Sweden.37 However, the popularity of these programs does not mean they always work.38 When MBO fails, the culprits tend to be unrealistic expectations, lack of commitment by top management, and inability or unwillingness to allocate rewards based on goal accomplishment.

Goal Setting and Ethics

The relationship between goal setting and ethics is quite complex: If we emphasize the attainment of goals, what is the cost? The answer is probably found in the standards we set for goal achievement. For example, when money is tied to goal attainment, we may focus on getting the money and become willing to compromise ourselves ethically. If instead we are primed with thoughts about how we are spending our time when we are pursuing the goal, we are more likely to act ethically.39 However, this result is limited to thoughts about how we are spending our time. If we are put under time pressure and worry about that, thoughts about time turn against us. Time pressure also increases as we are nearing a goal, which can tempt us to act unethically to achieve it.40 Specifically, we may forego mastering tasks and adopt avoidance techniques so we don’t look bad,41 both of which can incline us toward unethical choices.