Using Alternative Work Arrangements to Motivate Employees

As you surely know, there are many approaches toward motivating people, and we’ve discussed some of them. Another approach to motivation is to consider alternative work arrangements such as flextime, job sharing, and telecommuting. These are likely to be especially important for a diverse workforce of dual-earner couples, single parents, and employees caring for sick or aging relatives.

Flextime

Susan is the classic “morning person.” Every day she rises at 5:00 a.m. sharp, full of energy. However, as she puts it, “I’m usually ready for bed right after the 7:00 p.m. news.” Her flexible work schedule as a claims processor at The Hartford Financial Services Group is perfect for her situation: her office opens at 6:00 a.m. and closes at 7:00 p.m., and she schedules her 8-hour day within this 13-hour period.

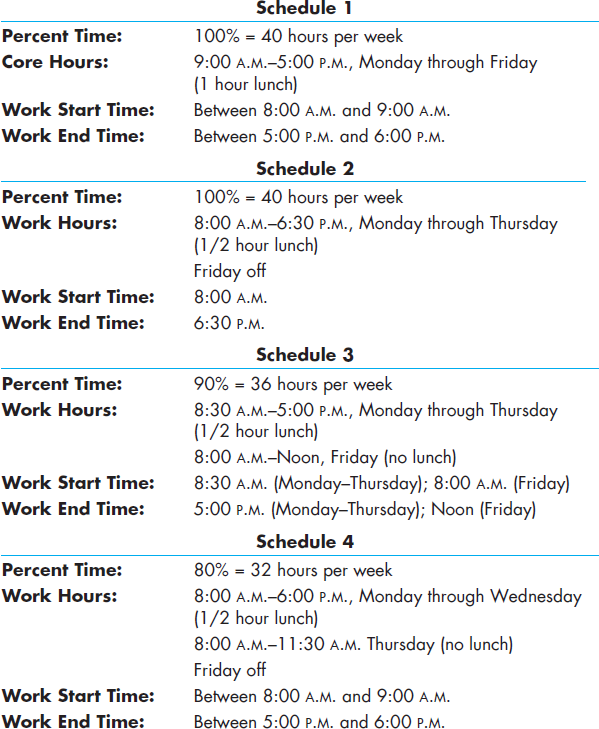

Susan’s schedule is an example of flextime, short for “flexible work time.” Flextime employees must work a specific number of hours per week but may vary their hours of work within limits. As in Exhibit 8-2, each day consists of a common core, usually six hours, with a flexibility band surrounding it. The core may be 9:00 a.m. to 3:00 p.m., with the office actually opening at 6:00 a.m. and closing at 6:00 p.m. Employees must be at their jobs during the common core period, but they may accumulate their other two hours around that. Some flextime programs allow employees to accumulate extra hours and turn them into days off.

Exhibit 8-2

Possible Flextime Staff Schedules

![]() Flextime has become extremely popular. According to a recent survey, a majority (60 percent) of U.S. organizations offer some form of flextime.16 This is not just a U.S. phenomenon, though. In Germany, for instance, 73 percent of businesses offer flextime, and such practices are becoming more widespread in Japan as well.17 In Germany, Belgium, the Netherlands, and France, by law employers are not allowed to refuse an employee’s request for either a part-time or a flexible work schedule as long as the request is reasonable, such as to care for an infant child.18

Flextime has become extremely popular. According to a recent survey, a majority (60 percent) of U.S. organizations offer some form of flextime.16 This is not just a U.S. phenomenon, though. In Germany, for instance, 73 percent of businesses offer flextime, and such practices are becoming more widespread in Japan as well.17 In Germany, Belgium, the Netherlands, and France, by law employers are not allowed to refuse an employee’s request for either a part-time or a flexible work schedule as long as the request is reasonable, such as to care for an infant child.18

![]() Most of the evidence stacks up favorably. Perhaps most important from the organization’s perspective, flextime increases profitability. Interestingly, though, this effect seems to occur only when flextime is promoted as a work–life balance strategy (not when it is for the organization’s gain).19 Flextime also tends to reduce absenteeism,20 probably for several reasons. Employees can schedule their work hours to align with personal demands, reducing tardiness and absences, and they can work when they are most productive. Flextime can also help employees balance work and family lives; in fact, it is a popular criterion for judging how “family friendly” a workplace is.

Most of the evidence stacks up favorably. Perhaps most important from the organization’s perspective, flextime increases profitability. Interestingly, though, this effect seems to occur only when flextime is promoted as a work–life balance strategy (not when it is for the organization’s gain).19 Flextime also tends to reduce absenteeism,20 probably for several reasons. Employees can schedule their work hours to align with personal demands, reducing tardiness and absences, and they can work when they are most productive. Flextime can also help employees balance work and family lives; in fact, it is a popular criterion for judging how “family friendly” a workplace is.

However, flextime is not applicable to every job or every worker. It is not a viable option for anyone whose service job requires being at a workstation at certain hours, for example. It also appears that people who have a strong desire to separate their work and family lives are less apt to want flextime, so it’s not a motivator for everyone.21 Also of note, research in the United Kingdom indicated that employees in organizations with flextime do not realize a reduction in their levels of stress, suggesting that this option may not truly improve work–life balance.22

Job Sharing

Job sharing allows two or more individuals to split a traditional full-time job. One employee might perform the job from 8:00 a.m. to noon, perhaps, and the other from 1:00 p.m. to 5:00 p.m., or the two could work full but alternate days. For example, top Ford engineers Julie Levine and Julie Rocco engaged in a job-sharing program that allowed both of them to spend time with their families while redesigning the Explorer crossover. Typically, one of them would work late afternoons and evenings while the other worked mornings. They both agreed that the program worked well, although making it feasible required a great deal of time and preparation.23

Only 18 percent of U.S. organizations offered job sharing in 2014, a 29 percent decrease since 2008.24 Reasons it is not more widely adopted include the difficulty of finding compatible partners to job share and the historically negative perceptions of job share individuals as not completely committed to their jobs and employers. However, eliminating job sharing for these reasons might be short-sighted. Job sharing allows an organization to draw on the talents of more than one individual for a given job. It opens the opportunity to acquire skilled workers—for instance, parents with young children and retirees—who might not be available on a full-time basis. From the employee’s perspective, job sharing can increase motivation and satisfaction.

![]() An employer’s decision to use job sharing is often based on economics and national policy. Two part-time employees sharing a job can be less expensive in terms of salary and benefits than one full-timer because training, coordination, and administrative costs can be high. On the other hand, in the United States the Affordable Care Act may create a financial incentive for companies to increase job-sharing arrangements in order to avoid the requirement to provide health care to full-time employees.25 Many German and Japanese26 firms have been using job sharing—but for a very different reason. Germany’s Kurzarbeit program, which is now close to 100 years old, kept employment levels from plummeting throughout the economic crisis by switching full-time workers to part-time job-sharing work.27

An employer’s decision to use job sharing is often based on economics and national policy. Two part-time employees sharing a job can be less expensive in terms of salary and benefits than one full-timer because training, coordination, and administrative costs can be high. On the other hand, in the United States the Affordable Care Act may create a financial incentive for companies to increase job-sharing arrangements in order to avoid the requirement to provide health care to full-time employees.25 Many German and Japanese26 firms have been using job sharing—but for a very different reason. Germany’s Kurzarbeit program, which is now close to 100 years old, kept employment levels from plummeting throughout the economic crisis by switching full-time workers to part-time job-sharing work.27

Telecommuting

It might be close to the ideal job for many people: no rush hour traffic, flexible hours, freedom to dress as you please, and few interruptions. Telecommuting refers to working at home—or anywhere else the employee chooses that is outside the workplace—at least two days a week on a computer linked to the employer’s office.28 (A closely related concept—working from a virtual office—describes working outside the workplace on a relatively permanent basis.) A sales manager working from home is telecommuting, but a sales manager working from her car on a business trip is not because the location is not by choice.

![]() While the movement away from telecommuting by some companies makes headlines, it appears that for most organizations, it remains popular. For example, almost 50 percent of managers in Germany, the United Kingdom, and the United States are permitted telecommuting options. Telecommuting is less of a practice in China, but there, too, it is growing.29 In developing countries, the telecommuting percentage is between 10 and 20 percent.30 Organizations that actively encourage telecommuting include Amazon, IBM, American Express,31 Intel, Cisco Systems,32 and a number of U.S. government agencies.33

While the movement away from telecommuting by some companies makes headlines, it appears that for most organizations, it remains popular. For example, almost 50 percent of managers in Germany, the United Kingdom, and the United States are permitted telecommuting options. Telecommuting is less of a practice in China, but there, too, it is growing.29 In developing countries, the telecommuting percentage is between 10 and 20 percent.30 Organizations that actively encourage telecommuting include Amazon, IBM, American Express,31 Intel, Cisco Systems,32 and a number of U.S. government agencies.33

From the employee’s standpoint, telecommuting can increase feelings of isolation and reduce job satisfaction.34 Research indicates it does not reduce work–family conflicts, though perhaps it is because telecommuting often increases work hours beyond the contracted workweek.35 Telecommuters are also vulnerable to the “out of sight, out of mind” effect: Employees who aren’t at their desks, miss impromptu meetings in the office, and don’t share in day-to-day informal workplace interactions may be at a disadvantage when it comes to raises and promotions because they’re perceived as not putting in the requisite “face time.”36 As for a CSR benefit of reducing car emissions by allowing telecommuting, research indicates that employees actually drive over 45 miles more per day, due to increased personal trips, when they telecommute!37