Services Marketing

Services have grown dramatically in recent years. Services now account for almost 80 percent of the U.S. gross domestic product (GDP). Services are growing even faster in the world economy, making up almost 63 percent of the gross world product.20

Service industries vary greatly. Governments offer services through courts, employment services, hospitals, military services, police and fire departments, the postal service, and schools. Private not-for-profit organizations offer services through museums, charities, churches, colleges, foundations, and hospitals. In addition, a large number of business organizations offer services—airlines, banks, hotels, insurance companies, consulting firms, medical and legal practices, entertainment and telecommunications companies, real estate firms, retailers, and others.

The Nature and Characteristics of a Service

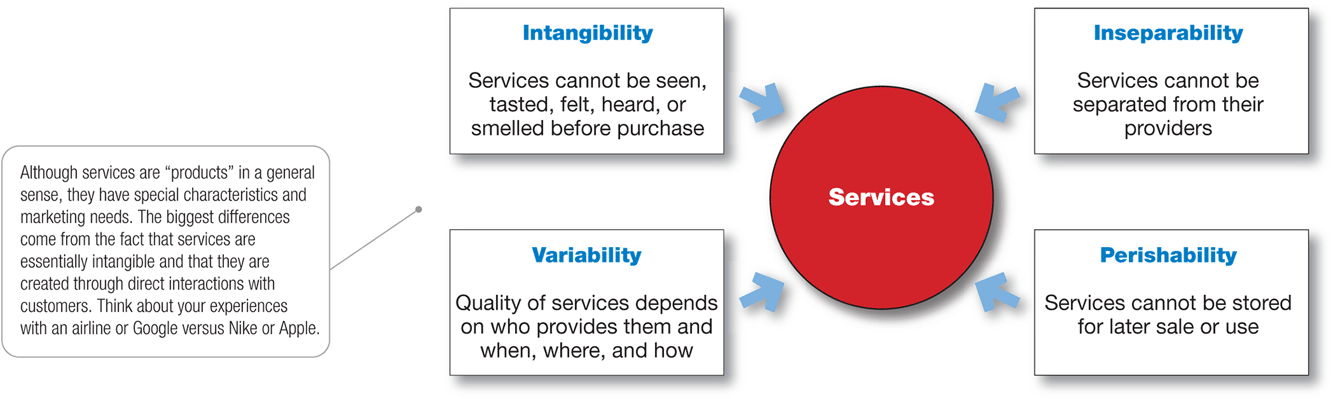

A company must consider four special service characteristics when designing marketing programs: intangibility, inseparability, variability, and perishability (see

![]() Figure 8.3).

Figure 8.3).

Figure 8.3

Figure 8.3

Four Service Characteristics

Service intangibility means that services cannot be seen, tasted, felt, heard, or smelled before they are bought. For example, people undergoing cosmetic surgery cannot see the result before the purchase. Airline passengers have nothing but a ticket and a promise that they and their luggage will arrive safely at the intended destination, hopefully at the same time. To reduce uncertainty, buyers look for signals of service quality. They draw conclusions about quality from the place, people, price, equipment, and communications that they can see.

Therefore, the service provider’s task is to make the service tangible in one or more ways and send the right signals about quality. The Mayo Clinic does this well:21

When it comes to hospitals, most patients can’t really judge “product quality.” It’s a very complex product that’s hard to understand, and you can’t try it out before buying it. So when considering a hospital, most people unconsciously search for evidence that the facility is caring, competent, and trustworthy. The Mayo Clinic doesn’t leave these things to chance. Rather, it offers patients organized and honest evidence of its dedication to “providing the best care to every patient every day.”

Inside, staff is trained to act in a way that clearly signals Mayo Clinic’s concern for patient well-being. For example, doctors regularly follow up with patients at home to see how they are doing, and they work with patients to smooth out scheduling problems. The clinic’s physical facilities also send the right signals. They’ve been carefully designed to offer a place of refuge, show caring and respect, and signal competence. Looking for external confirmation? Go online and hear directly from those who’ve been to the clinic or work there. The Mayo Clinic uses social networking—everything from blogs to Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, Instagram, and Pinterest—to enhance the patient experience.

For example, on the Sharing Mayo Clinic blog (http://sharing.mayoclinic.org), patients and their families retell their Mayo experiences, and Mayo employees offer behind-the-scenes views. The result? Highly loyal customers who willingly spread the good word to others, building one of the most powerful brands in health care.

Physical goods are produced, then stored, then later sold, and then still later consumed. In contrast, services are first sold and then produced and consumed at the same time. Service inseparability means that services cannot be separated from their providers, whether the providers are people or machines. If a service employee provides the service, then the employee becomes a part of the service. And customers don’t just buy and use a service; they play an active role in its delivery. Customer coproduction makes provider–customer interaction a special feature of services marketing. Both the provider and the customer affect the service outcome.

By providing customers with organized, honest evidence of its capabilities, the Mayo Clinic has built one of the most powerful brands in health care. Its Sharing Mayo Clinic blog lets you hear directly from those who have been to the clinic or who work there.

By providing customers with organized, honest evidence of its capabilities, the Mayo Clinic has built one of the most powerful brands in health care. Its Sharing Mayo Clinic blog lets you hear directly from those who have been to the clinic or who work there.

Mayo Clinic

Service variability means that the quality of services depends on who provides them as well as when, where, and how they are provided. For example, some hotels—say, Marriott—have reputations for providing better service than others. Still, within a given Marriott hotel, one registration-counter employee may be cheerful and efficient, whereas another standing just a few feet away may be grumpy and slow. Even the quality of a single Marriott employee’s service varies according to his or her energy and frame of mind at the time of each customer encounter.

Service perishability means that services cannot be stored for later sale or use. Some doctors charge patients for missed appointments because the service value existed only at that point and disappeared when the patient did not show up. The perishability of services is not a problem when demand is steady. However, when demand fluctuates, service firms often have difficult problems. For example, because of rush-hour demand, public transportation companies have to own much more equipment than they would if demand were even throughout the day. Thus, service firms often design strategies for producing a better match between demand and supply. Hotels and resorts charge lower prices in the off-season to attract more guests. And restaurants hire part-time employees to serve during peak periods.

Marketing Strategies for Service Firms

Just like manufacturing businesses, good service firms use marketing to position themselves strongly in chosen target markets. Enterprise Rent-A-Car gives you “Car rental and much more”; Zipcar offers “Wheels when you want them.” At CVS Pharmacy, “Expect something extra”; Walgreens meets you “at the corner of happy & healthy.” And St. Jude Children’s Hospital is “Finding cures. Saving children.” These and other service firms establish their positions through traditional marketing mix activities. However, because services differ from tangible products, they often require additional marketing approaches.

The Service Profit Chain

In a service business, the customer and the front-line service employee interact to co-create the service. Effective interaction, in turn, depends on the skills of front-line service employees and on the support processes backing these employees. Thus, successful service companies focus their attention on both their customers and their employees. They understand the service profit chain, which links service firm profits with employee and customer satisfaction. This chain consists of five links:22

Internal service quality. Superior employee selection and training, a quality work environment, and strong support for those dealing with customers, which results in . . .

Satisfied and productive service employees. More satisfied, loyal, and hardworking employees, which results in . . .

Greater service value. More effective and efficient customer value creation, engagement, and service delivery, which results in . . .

Satisfied and loyal customers. Satisfied customers who remain loyal, make repeat purchases, and refer other customers, which results in . . .

Healthy service profits and growth. Superior service firm performance.

For example, customer-service all-star Zappos.com—the online shoes, clothing, and accessories retailers—knows that happy customers and profits begin with happy, dedicated, energetic employees (see Real Marketing 8.2). Similarly, at Four Seasons Hotels and Resorts, creating delighted customers involves much more than just crafting a lofty customer-focused marketing strategy and handing it down from the top. At Four Seasons, satisfying customers is everybody’s business. And it all starts with satisfied employees:23

Four Seasons has perfected the art of high-touch, carefully crafted service. Whether it’s at the tropical island paradise at the Four Seasons Resort Mauritius or the luxurious sub-Saharan “camp” at the Four Seasons Safari Lodge Serengeti, guests paying $1,000 or more a night expect to have their minds read. For these guests, Four Seasons doesn’t disappoint. As one Four Seasons Maui guest once told a manager, “If there’s a heaven, I hope it’s run by Four Seasons.” What makes Four Seasons so special? It’s really no secret. It’s the quality of the Four Seasons staff. Four Seasons knows that happy, satisfied employees make for happy, satisfied customers. So just as it does for customers, Four Seasons respects and pampers its employees.

Four Seasons hires the best people, pays them well, orients them carefully, instills in them a sense of pride, and rewards them for outstanding service deeds. It treats employees as it would its most important guests. For example, all employees—from the maids who make up the rooms to the general manager—dine together (free of charge) in the hotel cafeteria. Perhaps best of all, every employee receives free stays at other Four Seasons resorts, six free nights per year after one year with the company. The room stays make employees feel as important and pampered as the guests they serve and motivate employees to achieve even higher levels of service in their own jobs. Says one Four Seasons staffer, “You come back from those trips on fire. You want to do so much for the guests.” As a result of such actions, the annual turnover for full-time employees at Four Seasons is only 18 percent, half the industry average. Four Seasons has been included for 18 straight years on Fortune magazine’s list of 100 Best Companies to Work For. And that’s the biggest secret to Four Seasons’ success.

Services marketing requires more than just traditional external marketing using the four Ps.

![]() Figure 8.4 shows that services marketing also requires internal marketing and interactive marketing. Internal marketing means that the service firm must orient and motivate its customer-contact employees and supporting service people to work as a team to provide customer satisfaction. Marketers must get everyone in the organization to be customer centered. In fact, internal marketing must precede external marketing. For example, Zappos starts by hiring the right people and carefully orienting and inspiring them to give unparalleled customer service. The idea is to make certain that employees themselves believe in the brand so that they can authentically deliver the brand’s promise to customers.

Figure 8.4 shows that services marketing also requires internal marketing and interactive marketing. Internal marketing means that the service firm must orient and motivate its customer-contact employees and supporting service people to work as a team to provide customer satisfaction. Marketers must get everyone in the organization to be customer centered. In fact, internal marketing must precede external marketing. For example, Zappos starts by hiring the right people and carefully orienting and inspiring them to give unparalleled customer service. The idea is to make certain that employees themselves believe in the brand so that they can authentically deliver the brand’s promise to customers.

Figure 8.4

Figure 8.4

Three Types of Services Marketing

Interactive marketing means that service quality depends heavily on the quality of the buyer–seller interaction during the service encounter. In product marketing, product quality often depends little on how the product is obtained. But in services marketing, service quality depends on both the service deliverer and the quality of delivery. Service marketers, therefore, have to master interactive marketing skills. Thus, Zappos selects only people with an innate “passion to serve” and instructs them carefully in the fine art of interacting with customers to satisfy their every need. All new hires—at all levels of the company—complete a four-week customer-loyalty training regimen.

Today, as competition and costs increase and as productivity and quality decrease, more services marketing sophistication is needed. Service companies face three major marketing tasks: They want to increase their service differentiation, service quality, and service productivity.

Managing Service Differentiation

In these days of intense price competition, service marketers often complain about the difficulty of differentiating their services from those of competitors. To the extent that customers view the services of different providers as similar, they care less about the provider than the price. The solution to price competition is to develop a differentiated offer, delivery, and image.

The offer can include innovative features that set one company’s offer apart from competitors’ offers. For example, some retailers differentiate themselves with offerings that take you well beyond the products they stock. Apple’s highly successful stores offer a Genius Bar for technical support and a host of free workshops on everything from iPhone, iPad, and Mac basics to the intricacies of using iMovie to turn home movies into blockbusters.

![]() Similarly, at any of several large REI stores, consumers can get hands-on experience with merchandise before buying it via the store’s mountain bike test trail, gear-testing stations, a huge rock climbing wall, or an in-store simulated rain shower.

Similarly, at any of several large REI stores, consumers can get hands-on experience with merchandise before buying it via the store’s mountain bike test trail, gear-testing stations, a huge rock climbing wall, or an in-store simulated rain shower.

At any of several large REI stores, consumers can get hands-on experience with merchandise before buying it via the store’s mountain bike test trail, gear-testing stations, a huge rock climbing wall, or an in-store simulated rain shower.

© Joshua Rainey / Alamy

Service companies can differentiate their service delivery by having more able and reliable customer-contact people, developing a superior physical environment in which the service product is delivered, or designing a superior delivery process. For example, many grocery chains now offer online shopping and home delivery as a better way to shop than having to drive, park, wait in line, and tote groceries home. And most banks offer mobile phone apps that allow you to more easily transfer money, check account balances, and make mobile check deposits. “Sign, snap a photo, and submit a check from anywhere,” says one Citibank ad. “It’s easier than running to the bank.”

Finally, service companies also can work on differentiating their images through symbols and branding. Aflac adopted the duck as its advertising symbol. Today, the duck is immortalized through stuffed animals, golf club covers, and free ringtones and screensavers. The well-known Aflac duck helped make the big but previously unknown insurance company memorable and approachable. Other well-known service characters and symbols include the GEICO gecko, Progressive Insurance’s Flo, McDonald’s golden arches, Allstate’s “good hands,” the Twitter bird, and the freckled, red-haired, pig-tailed Wendy’s girl. Progressive’s Flo has amassed more the 5 million Facebook Likes.

Managing Service Quality

A service firm can differentiate itself by delivering consistently higher quality than its competitors provide. Like manufacturers before them, most service industries have now joined the customer-driven quality movement. And like product marketers, service providers need to identify what target customers expect in regard to service quality.

Unfortunately, service quality is harder to define and judge than product quality. For instance, it is harder to agree on the quality of a haircut than on the quality of a hair dryer. Customer retention is perhaps the best measure of quality; a service firm’s ability to hang onto its customers depends on how consistently it delivers value to them.

Top service companies set high service-quality standards. They watch service performance closely, both their own and that of competitors. They do not settle for merely good service—they strive for 100 percent defect-free service. A 98 percent performance standard may sound good, but using this standard, the U.S. Postal Service would lose or misdirect 356,000 pieces of mail each hour, and U.S. pharmacies would misfill more than 1.5 million prescriptions each week.24

Unlike product manufacturers who can adjust their machinery and inputs until everything is perfect, service quality will always vary, depending on the interactions between employees and customers. As hard as they may try, even the best companies will have an occasional late delivery, burned steak, or grumpy employee. However, good service recovery can turn angry customers into loyal ones. In fact, good recovery can win more customer purchasing and loyalty than if things had gone well in the first place.

For example, Southwest Airlines has a proactive customer communications team whose job is to find the situations in which something went wrong—a mechanical delay, bad weather, a medical emergency, or a berserk passenger—then remedy the bad experience quickly, within 24 hours if possible.25 The team’s communications to passengers, usually emails or texts these days, have three basic components: a sincere apology, a brief explanation of what happened, and a gift to make it up, usually a voucher in dollars that can be used on their next Southwest flight. Surveys show that when Southwest handles a delay situation well, customers score it 14 to 16 points higher than on regular on-time flights.

These days, social media such as Facebook and Twitter can help companies root out and remedy customer dissatisfaction with service. As discussed in Chapter 4, companiesnow monitor the digital space to spot customer issues quickly and respond in real time. For example, Southwest has a dedicated team of 29 people who respond to roughly 80,000 Facebook and Twitter posts monthly. A quick and thoughtful response can turn a dissatisfied customer into a brand advocate.26

Managing service productivity: Companies should be careful not to take things too far. For example, in their attempts to improve productivity, some airlines have mangled customer service.

Managing service productivity: Companies should be careful not to take things too far. For example, in their attempts to improve productivity, some airlines have mangled customer service.

DPA/Stringer/Getty Images

Managing Service Productivity

With their costs rising rapidly, service firms are under great pressure to increase service productivity. They can do so in several ways. They can train current employees better or hire new ones who will work harder or more skillfully. Or they can increase the quantity of their service by giving up some quality. Finally, a service provider can harness the power of technology. Although we often think of technology’s power to save time and costs in manufacturing companies, it also has great—and often untapped—potential to make service workers more productive.

However, companies must avoid pushing productivity so hard that doing so reduces quality. Attempts to streamline a service or cut costs can make a service company more efficient in the short run. But that can also reduce its longer-run ability to innovate, maintain service quality, or respond to consumer needs and desires.

![]() For example, some airlines have learned this lesson the hard way as they attempt to economize in the face of rising costs. Passengers on most airlines now encounter “time-saving” check-in kiosks rather than personal counter service. And most airlines have stopped offering even the little things for free—such as in-flight snacks—and now charge extra for everything from checked luggage to aisle seats. The result is a plane full of disgruntled customers. In their attempts to improve productivity, many airlines have mangled customer service.

For example, some airlines have learned this lesson the hard way as they attempt to economize in the face of rising costs. Passengers on most airlines now encounter “time-saving” check-in kiosks rather than personal counter service. And most airlines have stopped offering even the little things for free—such as in-flight snacks—and now charge extra for everything from checked luggage to aisle seats. The result is a plane full of disgruntled customers. In their attempts to improve productivity, many airlines have mangled customer service.

Thus, in attempting to improve service productivity, companies must be mindful of how they create and deliver customer value. They should be careful not to take service out of the service. In fact, a company may purposely lower service productivity in order to improve service quality, in turn allowing it to maintain higher prices and profit margins.