Major Pricing Strategies

The price the company charges will fall somewhere between one that is too low to produce a profit and one that is too high to produce any demand.

![]() Figure 10.1 summarizes the major considerations in setting prices. Customer perceptions of the product’s value set the ceiling for its price. If customers perceive that the product’s price is greater than its value, they will not buy the product. Likewise, product costs set the floor for a product’s price. If the company prices the product below its costs, the company’s profits will suffer. In setting its price between these two extremes, the company must consider several external and internal factors, including competitors’ strategies and prices, the overall marketing strategy and mix, and the nature of the market and demand.

Figure 10.1 summarizes the major considerations in setting prices. Customer perceptions of the product’s value set the ceiling for its price. If customers perceive that the product’s price is greater than its value, they will not buy the product. Likewise, product costs set the floor for a product’s price. If the company prices the product below its costs, the company’s profits will suffer. In setting its price between these two extremes, the company must consider several external and internal factors, including competitors’ strategies and prices, the overall marketing strategy and mix, and the nature of the market and demand.

Figure 10.1

Figure 10.1

Considerations in Setting Price

Figure 10.1 suggests three major pricing strategies: customer value–based pricing, cost-based pricing, and competition-based pricing.

Customer Value–Based Pricing

In the end, the customer will decide whether a product’s price is right. Pricing decisions, like other marketing mix decisions, must start with customer value. When customers buy a product, they exchange something of value (the price) to get something of value (the benefits of having or using the product). Effective customer-oriented pricing involves understanding how much value consumers place on the benefits they receive from the product and setting a price that captures that value.

Customer value–based pricing uses buyers’ perceptions of value as the key to pricing. Value-based pricing means that the marketer cannot design a product and marketing program and then set the price. Price is considered along with all other marketing mix variables before the marketing program is set.

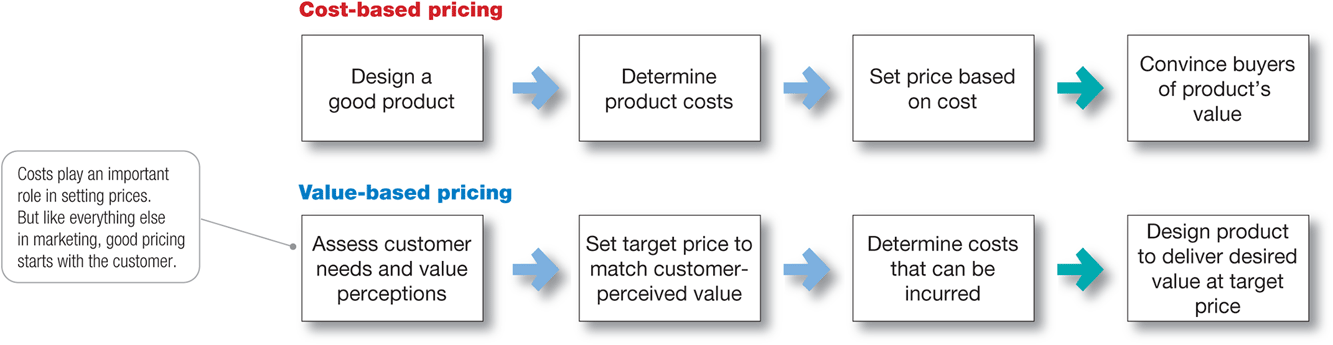

![]() Figure 10.2 compares value-based pricing with cost-based pricing. Although costs are an important consideration in setting prices, cost-based pricing is often product driven. The company designs what it considers to be a good product, adds up the costs of making the product, and sets a price that covers costs plus a target profit. Marketing must then convince buyers that the product’s value at that price justifies its purchase. If the price turns out to be too high, the company must settle for lower markups or lower sales, both resulting in disappointing profits.

Figure 10.2 compares value-based pricing with cost-based pricing. Although costs are an important consideration in setting prices, cost-based pricing is often product driven. The company designs what it considers to be a good product, adds up the costs of making the product, and sets a price that covers costs plus a target profit. Marketing must then convince buyers that the product’s value at that price justifies its purchase. If the price turns out to be too high, the company must settle for lower markups or lower sales, both resulting in disappointing profits.

Figure 10.2

Figure 10.2

Value-Based Pricing versus Cost-Based Pricing

Value-based pricing reverses this process. The company first assesses customer needs and value perceptions. It then sets its target price based on customer perceptions of value. The targeted value and price drive decisions about what costs can be incurred and the resulting product design. As a result, pricing begins with analyzing consumer needs and value perceptions, and the price is set to match perceived value.

It’s important to remember that “good value” is not the same as “low price.”

![]() For example, some owners consider a luxurious Patek Philippe watch a real bargain, even at eye-popping prices ranging from $20,000 to $500,000:3

For example, some owners consider a luxurious Patek Philippe watch a real bargain, even at eye-popping prices ranging from $20,000 to $500,000:3

Perceived value: Some owners consider a luxurious Patek Philippe watch a real bargain, even at eye-popping prices ranging from $20,000 to $500,000.

Perceived value: Some owners consider a luxurious Patek Philippe watch a real bargain, even at eye-popping prices ranging from $20,000 to $500,000.

FABRICE COFFRINI/AFP/Getty Images

Listen up here, because I’m about to tell you why a certain watch costing $20,000, or even $500,000, isn’t actually expensive but is in fact a tremendous value. Every Patek Philippe watch is handmade by Swiss watchmakers from the finest materials and can take more than a year to make. Still not convinced? Beyond keeping precise time, Patek Philippe watches are also good investments. They carry high prices but retain or even increase their value over time. Many models achieve a kind of cult status that makes them the most coveted timepieces on the planet. But more important than just a means of telling time or a good investment is the sentimental and emotional value of possessing a Patek Philippe. Says the company’s president: “This is about passion. I mean—it really is a dream. Nobody needs a Patek.” These watches are unique possessions steeped in precious memories, making them treasured family assets. According to the company, “The purchase of a Patek Philippe is often related to a personal event—a professional success, a marriage, or the birth of a child—and offering it as a gift is the most eloquent expression of love or affection.” A Patek Philippe watch is made not to last just one lifetime but many. Says one ad: “You never actually own a Patek Philippe, you merely look after it for the next generation.” That makes it a real bargain, even at twice the price.

A company will often find it hard to measure the value customers attach to its product. For example, calculating the cost of ingredients in a meal at a fancy restaurant is relatively easy. But assigning value to other measures of satisfaction such as taste, environment, relaxation, conversation, and status is very hard. Such value is subjective; it varies both for different consumers and different situations.

Still, consumers will use these perceived values to evaluate a product’s price, so the company must work to measure them. Sometimes, companies ask consumers how much they would pay for a basic product and for each benefit added to the offer. Or a company might conduct experiments to test the perceived value of different product offers. According to an old Russian proverb, there are two fools in every market—one who asks too much and one who asks too little. If the seller charges more than the buyers’ perceived value, the company’s sales will suffer. If the seller charges less, its products will sell very well, but they will produce less revenue than they would if they were priced at the level of perceived value.

We now examine two types of value-based pricing: good-value pricing and value-added pricing.

Good-Value Pricing

The Great Recession of 2008 to 2009 caused a fundamental and lasting shift in consumer attitudes toward price and quality. In response, many companies have changed their pricing approaches to bring them in line with changing economic conditions and consumer price perceptions. More and more, marketers have adopted the strategy of good-value pricing—offering the right combination of quality and good service at a fair price.

In many cases, this has involved introducing less-expensive versions of established brand name products or new lower-price lines. For example, Walmart launched an extreme-value store brand called Price First. Priced even lower than the retailer’s already-low-priced Great Value brand, Price First offers thrift-conscious customers rock-bottom prices on grocery staples. Good-value prices are a relative thing—even premium brands can launch value versions.

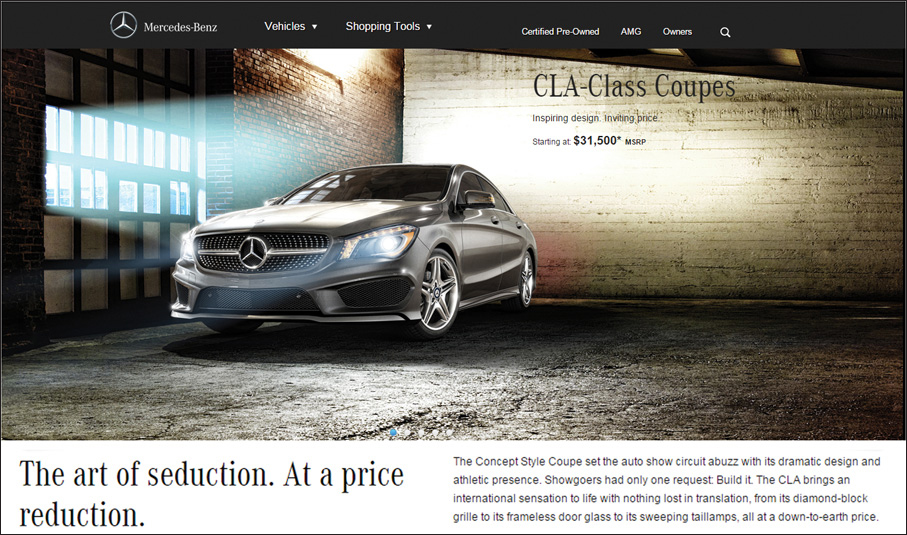

![]() Mercedes-Benz recently released its CLA Class, entry-level models starting at $31,500. From its wing-like dash and diamond-block grille to its 208-hp turbo inline-4 engine, the CLA Class gives customers “The Art of Seduction. At a price reduction.”4

Mercedes-Benz recently released its CLA Class, entry-level models starting at $31,500. From its wing-like dash and diamond-block grille to its 208-hp turbo inline-4 engine, the CLA Class gives customers “The Art of Seduction. At a price reduction.”4

Good-value pricing: Even premium brands can launch good-value versions. The Mercedes CLA Class gives customers “The Art of Seduction. At a price reduction.”

Good-value pricing: Even premium brands can launch good-value versions. The Mercedes CLA Class gives customers “The Art of Seduction. At a price reduction.”

© Courtesy of Daimler AG

In other cases, good-value pricing involves redesigning existing brands to offer more quality for a given price or the same quality for less. Some companies even succeed by offering less value but at very low prices. For example, Spirit Airlines gives customers “Bare Fare” pricing, by which they get less but don’t pay for what they don’t get (see Real Marketing 10.1).

An important type of good-value pricing at the retail level is called everyday low pricing (EDLP). EDLP involves charging a constant, everyday low price with few or no temporary price discounts. The ALDI supermarket chain practices EDLP, with a good-value pricing value proposition that gives customers “more ‘mmm’ for the dollar” every minute of every day. Perhaps the king of EDLP is Walmart, which practically defined the concept. Except for a few sale items every month, Walmart promises everyday low prices on everything it sells. In contrast, high-low pricing involves charging higher prices on an everyday basis but running frequent promotions to lower prices temporarily on selected items. Department stores such as Kohl’s and JCPenney practice high-low pricing by having frequent sale days, early-bird savings, and bonus earnings for store credit-card holders.

Value-Added Pricing

Value-based pricing doesn’t mean simply charging what customers want to pay or setting low prices to meet competition. Instead, many companies adopt value-added pricing strategies. Rather than cutting prices to match competitors, they add quality, services, and value-added features to differentiate their offers and thus support their higher prices.

Value-added pricing: Premium audio brand Bose creates “better sound through research—an innovative, high-quality listening experience,” adding value that merits its premium prices.

Value-added pricing: Premium audio brand Bose creates “better sound through research—an innovative, high-quality listening experience,” adding value that merits its premium prices.

Image used with permission of Bose Corporation.

![]() For example, premium audio brand Bose doesn’t try to beat out its competition by offering discounts or by selling lower-end, more affordable versions of its speakers, headphones, and home theater system products. Instead, for more than 50 years, Bose has poured resources into research and innovation to create high-quality products that merit the premium prices it charges. Bose’s goal is to create “better sound through research—an innovative, high-quality listening experience,” says the company. “We’re passionate engineers, developers, researchers, retailers, marketers . . . and dreamers. One goal unites us—to create products and experiences our customers simply can’t get anywhere else.” As a result, Bose has hatched a long list of groundbreaking innovations and high-quality products that bring added value to its customers. Despite its premium prices, or perhaps because of them, Bose remains a consistent leader in the markets it serves.5

For example, premium audio brand Bose doesn’t try to beat out its competition by offering discounts or by selling lower-end, more affordable versions of its speakers, headphones, and home theater system products. Instead, for more than 50 years, Bose has poured resources into research and innovation to create high-quality products that merit the premium prices it charges. Bose’s goal is to create “better sound through research—an innovative, high-quality listening experience,” says the company. “We’re passionate engineers, developers, researchers, retailers, marketers . . . and dreamers. One goal unites us—to create products and experiences our customers simply can’t get anywhere else.” As a result, Bose has hatched a long list of groundbreaking innovations and high-quality products that bring added value to its customers. Despite its premium prices, or perhaps because of them, Bose remains a consistent leader in the markets it serves.5

Cost-Based Pricing

Whereas customer value perceptions set the price ceiling, costs set the floor for the price that the company can charge. Cost-based pricing involves setting prices based on the costs of producing, distributing, and selling the product plus a fair rate of return for the company’s effort and risk. A company’s costs may be an important element in its pricing strategy.

Some companies, such as Walmart or Spirit Airlines, work to become the low-cost producers in their industries. Companies with lower costs can set lower prices that result in smaller margins but greater sales and profits. However, other companies—such as Apple, BMW, and Steinway—intentionally pay higher costs so that they can add value and claim higher prices and margins. For example, it costs more to make a “handcrafted” Steinway piano than a Yamaha production model. But the higher costs result in higher quality, justifying an average $87,000 price. To those who buy a Steinway, price is nothing; the Steinway experience is everything. The key is to manage the spread between costs and prices—how much the company makes for the customer value it delivers.

Types of Costs

A company’s costs take two forms: fixed and variable. Fixed costs (also known as overhead) are costs that do not vary with production or sales level. For example, a company must pay each month’s bills for rent, heat, interest, and executive salaries regardless of the company’s level of output. Variable costs vary directly with the level of production. Each smartphone or tablet produced by Samsung involves a cost of computer chips, wires, plastic, packaging, and other inputs. Although these costs tend to be the same for each unit produced, they are called variable costs because the total varies with the number of units produced. Total costs are the sum of the fixed and variable costs for any given level of production. Management wants to charge a price that will at least cover the total production costs at a given level of production.

The company must watch its costs carefully. If it costs the company more than its competitors to produce and sell a similar product, the company will need to charge a higher price or make less profit, putting it at a competitive disadvantage.

Costs at Different Levels of Production

To price wisely, management needs to know how its costs vary with different levels of production. For example, suppose Lenovo built a plant to produce 1,000 tablet computers per day.

![]() Figure 10.3A shows the typical short-run average cost curve (SRAC). It shows that the cost per tablet is high if Lenovo’s factory produces only a few per day. But as production moves up to 1,000 tablets per day, the average cost per unit decreases. This is because fixed costs are spread over more units, with each one bearing a smaller share of the fixed cost. Lenovo can try to produce more than 1,000 tablets per day, but average costs will increase because the plant becomes inefficient. Workers have to wait for machines, the machines break down more often, and workers get in each other’s way.

Figure 10.3A shows the typical short-run average cost curve (SRAC). It shows that the cost per tablet is high if Lenovo’s factory produces only a few per day. But as production moves up to 1,000 tablets per day, the average cost per unit decreases. This is because fixed costs are spread over more units, with each one bearing a smaller share of the fixed cost. Lenovo can try to produce more than 1,000 tablets per day, but average costs will increase because the plant becomes inefficient. Workers have to wait for machines, the machines break down more often, and workers get in each other’s way.

Figure 10.3

Figure 10.3

Cost per Unit at Different Levels of Production per Period

If Lenovo believed it could sell 2,000 tablets a day, it should consider building a larger plant. The plant would use more efficient machinery and work arrangements. Also, the unit cost of producing 2,000 tablets per day would be lower than the unit cost of producing 1,000 units per day, as shown in the long-run average cost (LRAC) curve (

![]() Figure 10.3B). In fact, a 3,000-capacity plant would be even more efficient, according to Figure 10.3B. But a 4,000-daily production plant would be less efficient because of increasing diseconomies of scale—too many workers to manage, paperwork slowing things down, and so on. Figure 10.3B shows that a 3,000-daily production plant is the best size to build if demand is strong enough to support this level of production.

Figure 10.3B). In fact, a 3,000-capacity plant would be even more efficient, according to Figure 10.3B. But a 4,000-daily production plant would be less efficient because of increasing diseconomies of scale—too many workers to manage, paperwork slowing things down, and so on. Figure 10.3B shows that a 3,000-daily production plant is the best size to build if demand is strong enough to support this level of production.

Costs as a Function of Production Experience

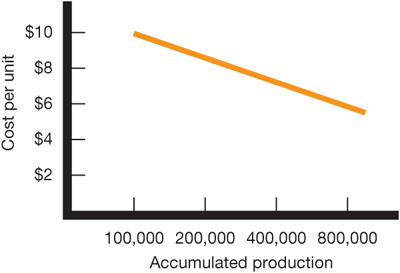

Suppose Lenovo runs a plant that produces 3,000 tablets per day. As Lenovo gains experience in producing tablets, it learns how to do it better. Workers learn shortcuts and become more familiar with their equipment. With practice, the work becomes better organized, and Lenovo finds better equipment and production processes. With higher volume, Lenovo becomes more efficient and gains economies of scale. As a result, the average cost tends to decrease with accumulated production experience. This is shown in

![]() Figure 10.4.6 Thus, the average cost of producing the first 100,000 tablets is $10 per tablet. When the company has produced the first 200,000 tablets, the average cost has fallen to $8.50. After its accumulated production experience doubles again to 400,000, the average cost is $7. This drop in the average cost with accumulated production experience is called the experience curve (or the learning curve).

Figure 10.4.6 Thus, the average cost of producing the first 100,000 tablets is $10 per tablet. When the company has produced the first 200,000 tablets, the average cost has fallen to $8.50. After its accumulated production experience doubles again to 400,000, the average cost is $7. This drop in the average cost with accumulated production experience is called the experience curve (or the learning curve).

Figure 10.4

Figure 10.4

Cost per Unit as a Function of Accumulated Production: The Experience Curve

If a downward-sloping experience curve exists, this is highly significant for the company. Not only will the company’s unit production cost fall, but it will fall faster if the company makes and sells more during a given time period. But the market has to stand ready to buy the higher output. And to take advantage of the experience curve, Lenovo must get a large market share early in the product’s life cycle. This suggests the following pricing strategy: Lenovo should price its tablets lower; its sales will then increase, its costs will decrease through gaining more experience, and then it can lower its prices further.

Some companies have built successful strategies around the experience curve. However, a single-minded focus on reducing costs and exploiting the experience curve will not always work. Experience-curve pricing carries some major risks. The aggressive pricing might give the product a cheap image. The strategy also assumes that competitors are weak and not willing to fight it out by meeting the company’s price cuts. Finally, while the company is building volume under one technology, a competitor may find a lower-cost technology that lets it start at prices lower than those of the market leader, which still operates on the old experience curve.

Cost-Plus Pricing

The simplest pricing method is cost-plus pricing (or markup pricing)—adding a standard markup to the cost of the product. Construction companies, for example, submit job bids by estimating the total project cost and adding a standard markup for profit. Lawyers, accountants, and other professionals typically price by adding a standard markup to their costs. Some sellers tell their customers they will charge cost plus a specified markup; for example, aerospace companies often price this way to the government.

To illustrate markup pricing, suppose a toaster manufacturer had the following costs and expected sales:

| Variable cost | $10 |

| Fixed costs | $300,000 |

| Expected unit sales | 50,000 |

Then the manufacturer’s cost per toaster is given by the following:

Now suppose the manufacturer wants to earn a 20 percent markup on sales. The manufacturer’s markup price is given by the following:7

The manufacturer would charge dealers $20 per toaster and make a profit of $4 per unit. The dealers, in turn, will mark up the toaster. If dealers want to earn 50 percent on the sales price, they will mark up the toaster to . This number is equivalent to a markup on cost of 100 percent

Does using standard markups to set prices make sense? Generally, no. Any pricing method that ignores demand and competitor prices is not likely to lead to the best price. Still, markup pricing remains popular for many reasons. First, sellers are more certain about costs than about demand. By tying the price to cost, sellers simplify pricing; they do not need to make frequent adjustments as demand changes. Second, when all firms in the industry use this pricing method, prices tend to be similar, so price competition is minimized. Third, many people feel that cost-plus pricing is fairer to both buyers and sellers. Sellers earn a fair return on their investment but do not take advantage of buyers when buyers’ demand becomes great.

Break-Even Analysis and Target Profit Pricing

Another cost-oriented pricing approach is break-even pricing (or a variation called target return pricing). The firm sets a price at which it will break even or make the target return on the costs of making and marketing a product.

Target return pricing uses the concept of a break-even chart, which shows the total cost and total revenue expected at different sales volume levels.

![]() Figure 10.5 shows a break-even chart for the toaster manufacturer discussed here. Fixed costs are $300,000 regardless of sales volume. Variable costs are added to fixed costs to form total costs, which rise with volume. The total revenue curve starts at zero and rises with each unit sold. The slope of the total revenue curve reflects the price of $20 per unit.

Figure 10.5 shows a break-even chart for the toaster manufacturer discussed here. Fixed costs are $300,000 regardless of sales volume. Variable costs are added to fixed costs to form total costs, which rise with volume. The total revenue curve starts at zero and rises with each unit sold. The slope of the total revenue curve reflects the price of $20 per unit.

Figure 10.5

Break-Even Chart for Determining Target Return Price and Break-Even Volume

The total revenue and total cost curves cross at 30,000 units. This is the break-even volume. At $20, the company must sell at least 30,000 units to break even, that is, for total revenue to cover total cost. Break-even volume can be calculated using the following formula:

If the company wants to make a profit, it must sell more than 30,000 units at $20 each. Suppose the toaster manufacturer has invested $1,000,000 in the business and wants to set a price to earn a 20 percent return, or $200,000. In that case, it must sell at least 50,000 units at $20 each. If the company charges a higher price, it will not need to sell as many toasters to achieve its target return. But the market may not buy even this lower volume at the higher price. Much depends on price elasticity and competitors’ prices.

The manufacturer should consider different prices and estimate break-even volumes, probable demand, and profits for each. This is done in

![]() Table 10.1. The table shows that as price increases, the break-even volume drops (column 2). But as price increases, the demand for toasters also decreases (column 3). At the $14 price, because the manufacturer clears only $4 per toaster ($14 less $10 in variable costs), it must sell a very high volume to break even. Even though the low price attracts many buyers, demand still falls below the high break-even point, and the manufacturer loses money. At the other extreme, with a $22 price, the manufacturer clears $12 per toaster and must sell only 25,000 units to break even. But at this high price, consumers buy too few toasters, and profits are negative. The table shows that a price of $18 yields the highest profits. Note that none of the prices produce the manufacturer’s target return of $200,000. To achieve this return, the manufacturer will have to search for ways to lower the fixed or variable costs, thus lowering the break-even volume.

Table 10.1. The table shows that as price increases, the break-even volume drops (column 2). But as price increases, the demand for toasters also decreases (column 3). At the $14 price, because the manufacturer clears only $4 per toaster ($14 less $10 in variable costs), it must sell a very high volume to break even. Even though the low price attracts many buyers, demand still falls below the high break-even point, and the manufacturer loses money. At the other extreme, with a $22 price, the manufacturer clears $12 per toaster and must sell only 25,000 units to break even. But at this high price, consumers buy too few toasters, and profits are negative. The table shows that a price of $18 yields the highest profits. Note that none of the prices produce the manufacturer’s target return of $200,000. To achieve this return, the manufacturer will have to search for ways to lower the fixed or variable costs, thus lowering the break-even volume.

Table 10.1

Table 10.1

Break-Even Volume and Profits at Different Prices

*Assumes fixed costs of $300,000 and constant unit variable costs of $10.

Competition-Based Pricing

Competition-based pricing involves setting prices based on competitors’ strategies, costs, prices, and market offerings. Consumers will base their judgments of a product’s value on the prices that competitors charge for similar products.

In assessing competitors’ pricing strategies, a company should ask several questions. First, how does the company’s market offering compare with competitors’ offerings in terms of customer value? If consumers perceive that the company’s product or service provides greater value, the company can charge a higher price. If consumers perceive less value relative to competing products, the company must either charge a lower price or change customer perceptions to justify a higher price.

Next, how strong are current competitors, and what are their current pricing strategies? If the company faces a host of smaller competitors charging high prices relative to the value they deliver, it might charge lower prices to drive weaker competitors from the market. If the market is dominated by larger, lower-price competitors, a company may decide to target unserved market niches by offering value-added products and services at higher prices.

Importantly, the goal is not to match or beat competitors’ prices. Rather, the goal is to set prices according to the relative value created versus competitors. If a company creates greater value for customers, higher prices are justified.

![]() For example, Caterpillar makes high-quality, heavy-duty construction and mining equipment. It dominates its industry despite charging higher prices than competitors such as Komatsu. When a commercial customer once asked a Caterpillar dealer why it should pay $500,000 for a big Caterpillar bulldozer when it could get an “equivalent” Komatsu dozer for $420,000, the Caterpillar dealer famously provided an analysis like the following:

For example, Caterpillar makes high-quality, heavy-duty construction and mining equipment. It dominates its industry despite charging higher prices than competitors such as Komatsu. When a commercial customer once asked a Caterpillar dealer why it should pay $500,000 for a big Caterpillar bulldozer when it could get an “equivalent” Komatsu dozer for $420,000, the Caterpillar dealer famously provided an analysis like the following:

Pricing versus competitors: Caterpillar dominates the heavy equipment industry despite charging premium prices. Customers believe that Caterpillar gives them a lot more value for the price over the lifetime of its machines.

Pricing versus competitors: Caterpillar dominates the heavy equipment industry despite charging premium prices. Customers believe that Caterpillar gives them a lot more value for the price over the lifetime of its machines.

© Kristoffer Tripplaar/Alamy

| $420,000 | the Caterpillar’s price if equivalent to the competitor’s bulldozer |

| $50,000 | the value added by Caterpillar’s superior reliability and durability |

| $40,000 | the value added by Caterpillar’s lower lifetime operating costs |

| $40,000 | the value added by Caterpillar’s superior service |

| $20,000 | the value added by Caterpillar’s longer parts warranty |

| $570,000 | the value-added price for Caterpillar’s bulldozer |

| discount | |

| $500,000 | final price |

Thus, although the customer pays an $80,000 price premium for the Caterpillar bulldozer, it’s actually getting $150,000 in added value over the product’s lifetime. The customer chose the Caterpillar bulldozer.

What principle should guide decisions about prices to charge relative to those of competitors? The answer is simple in concept but often difficult in practice: No matter what price you charge—high, low, or in between—be certain to give customers superior value for that price.