Product and Service Decisions

Marketers make product and service decisions at three levels: individual product decisions, product line decisions, and product mix decisions. We discuss each in turn.

Individual Product and Service Decisions

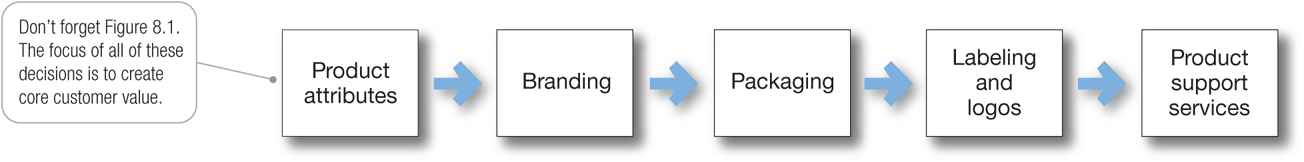

![]() Figure 8.2 shows the important decisions in the development and marketing of individual products and services. We will focus on decisions about product attributes, branding, packaging, labeling and logos, and product support services.

Figure 8.2 shows the important decisions in the development and marketing of individual products and services. We will focus on decisions about product attributes, branding, packaging, labeling and logos, and product support services.

Figure 8.2

Figure 8.2

Individual Product Decisions

Product and Service Attributes

Developing a product or service involves defining the benefits that it will offer. These benefits are communicated and delivered by product attributes such as quality, features, and style and design.

Product Quality

Product quality is one of the marketer’s major positioning tools. Quality affects product or service performance; thus, it is closely linked to customer value and satisfaction. In the narrowest sense, quality can be defined as “no defects.” But most marketers go beyond this narrow definition. Instead, they define quality in terms of creating customer value and satisfaction. The American Society for Quality defines quality as the characteristics of a product or service that bear on its ability to satisfy stated or implied customer needs. Similarly, Siemens defines quality this way: “Quality is when our customers come back and our products don’t.”7

Total quality management (TQM) is an approach in which all of the company’s people are involved in constantly improving the quality of products, services, and business processes. For most top companies, customer-driven quality has become a way of doing business. Today, companies are taking a return-on-quality approach, viewing quality as an investment and holding quality efforts accountable for bottom-line results.

Product quality has two dimensions: level and consistency. In developing a product, the marketer must first choose a quality level that will support the product’s positioning. Here, product quality means performance quality—the product’s ability to perform its functions. For example, a Rolls-Royce provides higher performance quality than a Chevrolet: It has a smoother ride, lasts longer, and provides more handcraftsmanship, custom design, luxury, and “creature comforts.” Companies rarely try to offer the highest possible performance quality level; few customers want or can afford the high levels of quality offered in products such as a Rolls-Royce automobile, a Viking range, or a Rolex watch. Instead, companies choose a quality level that matches target market needs and the quality levels of competing products.

Beyond quality level, high quality also can mean high levels of quality consistency. Here, product quality means conformance quality—freedom from defects and consistency in delivering a targeted level of performance. All companies should strive for high levels of conformance quality. In this sense, a Chevrolet can have just as much quality as a Rolls-Royce. Although a Chevy doesn’t perform at the same level as a Rolls-Royce, it can just as consistently deliver the quality that customers pay for and expect.

By consistently meeting or exceeding customers’ quality expectations, Chick-fil-A has won a trophy case full of awards for top food and service quality, helping it build a fierce following of loyal customers.

By consistently meeting or exceeding customers’ quality expectations, Chick-fil-A has won a trophy case full of awards for top food and service quality, helping it build a fierce following of loyal customers.

Bloomberg/Getty Images

![]() Similarly, the Chick-fil-A fast-food chain doesn’t aspire to provide gourmet dining experiences. However, by consistently meeting or exceeding customers’ quality expectations, the chain has earned a trophy case full of awards for top food and service quality. Last year, for instance, the chain was the only restaurant named to 24/7 Wall Street’s Customer Service Hall of Fame, based on a survey of 2,500 adults asked about the quality of customer service at 150 of America’s best-known companies across 15 industries. Chick-fil-A placed second overall, alongside the likes of Amazon, Marriott, and Apple.8 Although it doesn’t try to be Ritz-Carlton, it does send its managers to the Ritz-Carlton quality training program, where they learn things such as how to greet customers and how to probe for and serve unexpressed needs. Such consistency in meeting quality expectations has helped Chick-fil-A build a following of fiercely loyal customers.

Similarly, the Chick-fil-A fast-food chain doesn’t aspire to provide gourmet dining experiences. However, by consistently meeting or exceeding customers’ quality expectations, the chain has earned a trophy case full of awards for top food and service quality. Last year, for instance, the chain was the only restaurant named to 24/7 Wall Street’s Customer Service Hall of Fame, based on a survey of 2,500 adults asked about the quality of customer service at 150 of America’s best-known companies across 15 industries. Chick-fil-A placed second overall, alongside the likes of Amazon, Marriott, and Apple.8 Although it doesn’t try to be Ritz-Carlton, it does send its managers to the Ritz-Carlton quality training program, where they learn things such as how to greet customers and how to probe for and serve unexpressed needs. Such consistency in meeting quality expectations has helped Chick-fil-A build a following of fiercely loyal customers.

Product Features

A product can be offered with varying features. A stripped-down model, one without any extras, is the starting point. The company can then create higher-level models by adding more features. Features are a competitive tool for differentiating the company’s product from competitors’ products. Being the first producer to introduce a valued new feature is one of the most effective ways to compete.

How can a company identify new features and decide which ones to add to its product? It should periodically survey buyers who have used the product and ask these questions: How do you like the product? Which specific features of the product do you like most? Which features could we add to improve the product? The answers to these questions provide the company with a rich list of feature ideas. The company can then assess each feature’s value to customers versus its cost to the company. Features that customers value highly in relation to costs should be added.

Product Style and Design

Another way to add customer value is through distinctive product style and design. Design is a larger concept than style. Style simply describes the appearance of a product. Styles can be eye catching or yawn producing. A sensational style may grab attention and produce pleasing aesthetics, but it does not necessarily make the product perform better. Unlike style, design is more than skin deep—it goes to the very heart of a product. Good design contributes to a product’s usefulness as well as to its looks.

Good design doesn’t start with brainstorming new ideas and making prototypes. Design begins with observing customers, understanding their needs, and shaping their product-use experience. Product designers should think less about technical product specifications and more about how customers will use and benefit from the product. For example, using smart design based on consumer needs, Sonos created a wireless, internet-enabled speaker system that’s easy to use and fills a whole house with great sound.

In the past, setting up a whole-house entertainment or sound system required routing wires through walls, floors, and ceilings, creating a big mess and lots of expense. And if you moved, you couldn’t take it with you. Enter Sonos, which took home-audio and theater systems to a new level worthy of the digital age. The innovative company created a wireless speaker system that’s not just stylish but also easy to set up, easy to use, and easy to move to meet changing needs. With Sonos, you can stream high-quality sound through a variety of stylish speakers anywhere in your home with just an app and a tap on your smartphone. Smart design has paid off handsomely for Sonos. Founded in 2002, over just the past two years the company’s sales have nearly tripled to an estimated $1 billion a year.9

Branding

Perhaps the most distinctive skill of professional marketers is their ability to build and manage brands. A brand is a name, term, sign, symbol, or design or a combination of these that identifies the maker or seller of a product or service. Consumers view a brand as an important part of a product, and branding can add value to a consumer’s purchase. Customers attach meanings to brands and develop brand relationships. As a result, brands have meaning well beyond a product’s physical attributes. Consider this story:10

The meaning of a strong brand: The “branded” and “unbranded” Joshua Bell. The premier musician packs concert halls at an average of $100 or more a seat but made only $32 as a street musician at a Washington, DC, metro station.

The meaning of a strong brand: The “branded” and “unbranded” Joshua Bell. The premier musician packs concert halls at an average of $100 or more a seat but made only $32 as a street musician at a Washington, DC, metro station.

(left) NBC via Getty Images; (right) The Washington Post/Getty Images

One Tuesday evening in January, Joshua Bell, one of the world’s finest violinists, played at Boston’s stately Symphony Hall before a packed audience who’d paid an average of $100 a seat. Based on the well-earned strength of the “Joshua Bell brand,” the talented musician routinely drew standing-room-only audiences at all of his performances around the world. Three days later, however, as part of a Washington Post social experiment, Bell found himself standing in a Washington, DC, metro station, dressed in jeans, a T-shirt, and a Washington Nationals baseball cap. As morning commuters streamed by, Bell pulled out his $4 million Stradivarius violin, set the open case at his feet, and began playing the same revered classics he’d played in Boston. During the next 45 minutes, some 1,100 people passed by but few stopped to listen. Bell earned a total of $32. No one recognized the “unbranded” Bell, so few appreciated his artistry. What does that tell you about the meaning of a strong brand?

Branding has become so strong that today hardly anything goes unbranded. Salt is packaged in branded containers, common nuts and bolts are packaged with a distributor’s label, and automobile parts—spark plugs, tires, filters—bear brand names that differ from those of the automakers. Even fruits, vegetables, dairy products, and poultry are branded—Cuties mandarin oranges, Dole Classic salads, Horizon Organic milk, Perdue chickens, and Eggland’s Best eggs.

Branding helps buyers in many ways. Brand names help consumers identify products that might benefit them. Brands also say something about product quality and consistency—buyers who always buy the same brand know that they will get the same features, benefits, and quality each time they buy. Branding also gives the seller several advantages. The seller’s brand name and trademark provide legal protection for unique product features that otherwise might be copied by competitors. Branding helps the seller to segment markets. For example, rather than offering just one general product to all consumers, Toyota can offer the different Lexus, Toyota, and Scion brands, each with numerous sub-brands—such as Avalon, Camry, Corolla, Prius, Yaris, Tundra, and Land Cruiser.

Finally, a brand name becomes the basis on which a whole story can be built about a product’s special qualities. For example, the Cuties brand of pint-sized mandarins sets itself apart from ordinary oranges by promising “Kids love Cuties because Cuties are made for kids.” They are a healthy snack that’s “perfect for little hands”: sweet, seedless, kid-sized, and easy to peel.11 Building and managing brands are perhaps the marketer’s most important tasks. We will discuss branding strategy in more detail later in the chapter.

Packaging

Packaging involves designing and producing the container or wrapper for a product. Traditionally, the primary function of the package was to hold and protect the product. In recent times, however, packaging has become an important marketing tool as well. Increased competition and clutter on retail store shelves means that packages must now perform many sales tasks—from attracting buyers to communicating brand positioning to closing the sale. Not every customer will see a brand’s advertising, social media pages, or other promotions. However, all consumers who buy and use a product will interact regularly with its packaging. Thus, the humble package represents prime marketing space.

Companies realize the power of good packaging to create immediate consumer recognition of a brand. For example, an average supermarket stocks about 42,000 items; the average Walmart supercenter carries 120,000 items. The typical shopper makes three out of four purchase decisions in stores and passes by some 300 items per minute. In this highly competitive environment, the package may be the seller’s best and last chance to influence buyers. So the package itself becomes an important promotional medium.12

Distinctive packaging may become an important part of a brand’s identity. An otherwise plain brown carton imprinted with only the familiar curved arrow from the Amazon.com logo—variously interpreted as “a to z” or even a smiley face—leaves no doubt as to who shipped the package sitting at your doorstep.

Distinctive packaging may become an important part of a brand’s identity. An otherwise plain brown carton imprinted with only the familiar curved arrow from the Amazon.com logo—variously interpreted as “a to z” or even a smiley face—leaves no doubt as to who shipped the package sitting at your doorstep.

© Lux Igitur/Alamy

Innovative packaging can give a company an advantage over competitors and boost sales. Distinctive packaging may even become an important part of a brand’s identity.

![]() For example, an otherwise plain brown carton imprinted with the familiar curved arrow from the Amazon.com logo—variously interpreted as “a to z” or even a smiley face—leaves no doubt as to who shipped the package sitting at your doorstep. And Tiffany’s distinctive blue boxes have come to embody the exclusive jewelry retailer’s premium legacy and positioning. As the company puts it, “Glimpsed on a busy street or resting in the palm of a hand, Tiffany Blue Boxes make hearts beat faster and epitomize Tiffany’s great heritage of elegance, exclusivity, and flawless craftsmanship.”13

For example, an otherwise plain brown carton imprinted with the familiar curved arrow from the Amazon.com logo—variously interpreted as “a to z” or even a smiley face—leaves no doubt as to who shipped the package sitting at your doorstep. And Tiffany’s distinctive blue boxes have come to embody the exclusive jewelry retailer’s premium legacy and positioning. As the company puts it, “Glimpsed on a busy street or resting in the palm of a hand, Tiffany Blue Boxes make hearts beat faster and epitomize Tiffany’s great heritage of elegance, exclusivity, and flawless craftsmanship.”13

Poorly designed packages can cause headaches for consumers and lost sales for the company. Think about all those hard-to-open packages, such as DVD cases sealed with impossibly sticky labels, packaging with finger-splitting wire twist-ties, or sealed plastic clamshell containers that cause “wrap rage” and send thousands of people to the hospital each year with lacerations and puncture wounds. Another packaging issue is overpackaging—as when a tiny USB flash drive in an oversized cardboard and plastic display package is delivered in a giant corrugated shipping carton. Overpackaging creates an incredible amount of waste, frustrating those who care about the environment.

Amazon offers Frustration-Free Packaging to alleviate both wrap rage and overpackaging. The online retailer works with more than 2,000 companies, such as Fisher-Price, Mattel, Unilever, Microsoft, and others, to create smaller, easy-to-open, recyclable packages that use less packaging material and no frustrating plastic clamshells or wire ties. It currently offers more than 200,000 such items and to date has shipped more than 75 million of them to 175 countries. In the process, the initiative has eliminated nearly 60 million square feet of cardboard and 25 million pounds of packaging waste.14

In recent years, product safety has also become a major packaging concern. We have all learned to deal with hard-to-open “childproof” packaging. Due to the rash of product tampering scares in the 1980s, most drug producers and food makers now put their products in tamper-resistant packages. In making packaging decisions, the company also must heed growing environmental concerns. Fortunately, many companies have gone “green” by reducing their packaging and using environmentally responsible packaging materials.

Labeling and Logos

Labels and logos range from simple tags attached to products to complex graphics that are part of the packaging. They perform several functions. At the very least, the label identifies the product or brand, such as the name Sunkist stamped on oranges. The label might also describe several things about the product—who made it, where it was made, when it was made, its contents, how it is to be used, and how to use it safely. Finally, the label might help to promote the brand and engage customers. For many companies, labels have become an important element in broader marketing campaigns.

Labels and brand logos can support the brand’s positioning and add personality to the brand. In fact, they can become a crucial element in the brand-customer connection. Customers often become strongly attached to logos as symbols of the brands they represent. Consider the feelings evoked by the logos of companies such as Google, Coca-Cola, Twitter, Apple, and Nike. Logos must be redesigned from time to time. For example, brands ranging from Yahoo!, eBay, and Southwest Airlines to Wendy’s, Pizza Hut, Black+Decker, and Hershey have successfully adapted their logos to keep them contemporary and to meet the needs of new digital devices and interactive platforms such as the mobile apps and social media (see Real Marketing 8.1).

However, companies must take care when changing such important brand symbols. Customers often form strong connections to the visual representations of their brands and may react strongly to changes.

![]() For example, a few years ago when Gap introduced a more contemporary redesign of its familiar old logo—the well-known white text on a blue square—customers went ballistic and imposed intense online pressure. Gap reinstated the old logo after only one week.

For example, a few years ago when Gap introduced a more contemporary redesign of its familiar old logo—the well-known white text on a blue square—customers went ballistic and imposed intense online pressure. Gap reinstated the old logo after only one week.

Brand labels and logos: When Gap tried to modernize its familiar old logo, customers went ballistic, highlighting the powerful connection people have to the visual representations of their beloved brands.

Brand labels and logos: When Gap tried to modernize its familiar old logo, customers went ballistic, highlighting the powerful connection people have to the visual representations of their beloved brands.

Jean Francois FREY/PHOTOPQR/L’ALSACE/Newscom

Along with the positives, there has been a long history of legal concerns about labels and packaging. The Federal Trade Commission Act of 1914 held that false, misleading, or deceptive labels or packages constitute unfair competition. Labels can mislead customers, fail to describe important ingredients, or fail to include needed safety warnings. As a result, several federal and state laws regulate labeling. The most prominent is the Fair Packaging and Labeling Act of 1966, which set mandatory labeling requirements, encouraged voluntary industry packaging standards, and allowed federal agencies to set packaging regulations in specific industries. The Nutritional Labeling and Educational Act of 1990 requires sellers to provide detailed nutritional information on food products, and recent sweeping actions by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) regulate the use of health-related terms such as low fat, light, high fiber, and organic. Sellers must ensure that their labels contain all the required information.

Product Support Services

Customer service is another element of product strategy. A company’s offer usually includes some support services, which can be a minor part or a major part of the total offering. Later in this chapter, we will discuss services as products in themselves. Here, we discuss services that augment actual products.

Support services are an important part of the customer’s overall brand experience. Lexus knows that good marketing doesn’t end with making a sale. Keeping customers happy after the sale is the key to building lasting relationships. Lexus believes that if you delight the customer, and continue to delight the customer, you will have a customer for life. So Lexus dealers across the country will go to almost any lengths to take care of customers and keep them coming back:15

The typical Lexus dealership is, well, anything but typical. For example, in addition to its Starbucks coffee shop, one Florida Lexus dealership features four massage chairs, two putting greens, two customer lounges, and a library. At another Lexus dealership in a nearby city, “guests” leave their cars with a valet and are then guided by a concierge to a European-style coffee bar offering complimentary espresso, cappuccino, and a selection of pastries prepared by a chef trained in Rome. But at Lexus, customer service goes much deeper than just dealership amenities. From the very start, Lexus set out to revolutionize the auto ownership experience.

Of course, Lexus knows that the best dealership visit is the one you never have to make. So it builds customer-pleasing cars to start with.

In its “Lexus Covenant,” the company vows that it will make “the finest cars ever built”—high-quality cars that need little servicing. However, the covenant also vows to value customers as important individuals and “treat each customer as we would a guest in our own home.” So, when a car does need servicing, Lexus goes out of its way to make it easy and painless. Most dealers will even pick up a car and then return it when the maintenance is finished. And the car comes back spotless, thanks to a complimentary cleaning. You might even be surprised to find that they’ve touched up a door ding to help restore the car to its fresh-from-the-factory luster.

By all accounts, Lexus has lived up to its ambitious customer-satisfaction promise. It has created what appear to be the world’s most satisfied car owners. Lexus regularly tops not just the industry quality ratings but also customer-satisfaction ratings in both the United States and globally. “My wife will never buy another car except a Lexus,” says one satisfied Lexus owner. “They come to our house, pick up the car, do an oil change, spiff it up, and bring it back. She’s sold for life.”

The first step in designing support services is to survey customers periodically to assess the value of current services and obtain ideas for new ones. Once the company has assessed the quality of various support services to customers, it can take steps to fix problems and add new services that will both delight customers and yield profits to the company.

Customer service: From the start, under the Lexus Covenant, Lexus’s high-quality support services create an unmatched car ownership experience and some of the world’s most satisfied car owners.

Customer service: From the start, under the Lexus Covenant, Lexus’s high-quality support services create an unmatched car ownership experience and some of the world’s most satisfied car owners.

Toyota Motor Sales, USA, Inc.

Many companies now use a sophisticated mix of phone, email, online, social media, mobile, and interactive voice and data technologies to provide support services that were not possible before. For example, home-improvement store Lowe’s offers a vigorous dose of customer service at both its store and online locations that makes shopping easier, answers customer questions, and handles problems. Customers can access Lowe’s extensive support by phone, email ([email protected]), website, mobile app, and Twitter via @LowesCares. The Lowe’s website and mobile app link to a buying guide and how-to library. In its stores, Lowe’s has equipped employees with 42,000 iPhones filled with custom apps and add-on hardware, letting them perform service tasks such as checking inventory at nearby stores, looking up specific customer purchase histories, sharing how-to videos, and checking competitor prices—all without leaving the customer’s side. Lowe’s is even experimenting with putting interactive, talking, moving robots in stores that can greet customers as they enter, answer even their most vexing questions, and guide them to whatever merchandise they are seeking.16

Product Line Decisions

Beyond decisions about individual products and services, product strategy also calls for building a product line. A product line is a group of products that are closely related because they function in a similar manner, are sold to the same customer groups, are marketed through the same types of outlets, or fall within given price ranges. For example, Nike produces several lines of athletic shoes and apparel, and Marriott offers several lines of hotels.

The major product line decision involves product line length—the number of items in the product line. The line is too short if the manager can increase profits by adding items; the line is too long if the manager can increase profits by dropping items. Managers need to analyze their product lines periodically to assess each item’s sales and profits and understand how each item contributes to the line’s overall performance.

A company can expand its product line in two ways: by line filling or line stretching. Product line filling involves adding more items within the present range of the line. There are several reasons for product line filling: reaching for extra profits, satisfying dealers, using excess capacity, being the leading full-line company, and plugging holes to keep out competitors. However, line filling is overdone if it results in cannibalization (eating up sales of the company’s own existing products) and customer confusion. The company should ensure that new items are noticeably different from existing ones.

Product line stretching occurs when a company lengthens its product line beyond its current range. The company can stretch its line downward, upward, or both ways. Companies located at the upper end of the market can stretch their lines downward. For example, Mercedes has stretched downward with the CLA line to draw in younger, first-time buyers. A company may stretch downward to plug a market hole that otherwise would attract a new competitor or to respond to a competitor’s attack on the upper end. Or it may add low-end products because it finds faster growth taking place in the low-end segments. Companies can also stretch their product lines upward. Sometimes, companies stretch upward to add prestige to their current products or to reap higher margins. P&G did that with brands such as Cascade dishwashing detergent and Dawn dish soap by adding “Platinum” versions at higher price points.

As they grow and expand, many company both stretch and fill their product lines. Consider BMW:17

Product line stretching and filling: Through skillful line stretching and filling, BMW now has brands and lines that successfully appeal to the rich, the super-rich, and the hope-to-be-rich.

Product line stretching and filling: Through skillful line stretching and filling, BMW now has brands and lines that successfully appeal to the rich, the super-rich, and the hope-to-be-rich.

BMW of North America

Over the years, BMW Group has transformed itself from a single-brand, five-model automaker into a powerhouse with three brands, 14 “Series,” and dozens of distinct models. The company has expanded downward with its MINI Cooper line and upward with Rolls-Royce. Its BMW line brims with models from the low end to the high end to everything in between.

The brand’s seven “Series” lines range from the entry-level 1-Series subcompact to the luxury-compact 3-Series to the midsize 5-Series sedan to the luxurious full-size 7-Series. In between, BMW has filled the gaps with its X1, X3, X4, X5, and X6 SUVs; M-Series performance models; the Z4 roadster; and the i3 and i8 hybrids. Thus, through skillful line stretching and filling, while staying within its premium positioning, BMW now has brands and lines that successfully appeal to the rich, the super-rich, and the hope-to-be-rich.

Product Mix Decisions

An organization with several product lines has a product mix. A product mix (or product portfolio) consists of all the product lines and items that a particular seller offers for sale. For example, Colgate-Palmolive is perhaps best known for its toothpaste and other oral care products. But, in fact, Colgate is a $17.3 billion consumer products company that makes and markets a full product mix consisting of dozens of familiar lines and brands. Colgate divides its overall product mix into four major lines: oral care, personal care, home care, and pet nutrition. Each product line consists of many brands and items.18

The product mix: Colgate-Palmolive’s nicely consistent product mix contains dozens of brands that constitute the “Colgate World of Care”—products that “every day, people like you trust to care for themselves and the ones they love.”

The product mix: Colgate-Palmolive’s nicely consistent product mix contains dozens of brands that constitute the “Colgate World of Care”—products that “every day, people like you trust to care for themselves and the ones they love.”

Bloomberg/Getty Images

A company’s product mix has four important dimensions: width, length, depth, and consistency. Product mix width refers to the number of different product lines the company carries.

![]() For example, Colgate markets a fairly wide product mix, consisting of dozens of brands that constitute the “Colgate World of Care”—products that “every day, people like you trust to care for themselves and the ones they love.” By contrast, GE manufactures as many as 250,000 items across a broad range of categories, from lightbulbs to medical equipment, jet engines, and diesel locomotives.

For example, Colgate markets a fairly wide product mix, consisting of dozens of brands that constitute the “Colgate World of Care”—products that “every day, people like you trust to care for themselves and the ones they love.” By contrast, GE manufactures as many as 250,000 items across a broad range of categories, from lightbulbs to medical equipment, jet engines, and diesel locomotives.

Product mix length refers to the total number of items a company carries within its product lines. Colgate carries several brands within each line. For example, its personal care line includes Softsoap liquid soaps and body washes, Irish Spring bar soaps, Speed Stick deodorants, and Skin Bracer, Afta, and Colgate toiletries and shaving products, among others. The Colgate home care line includes Palmolive and AJAX dishwashing products, Suavitel fabric conditioners, and AJAX and Murphy Oil Soap cleaners. The pet nutrition line houses the Hills and Science Diet pet food brands.

Product line depth refers to the number of versions offered of each product in the line. Colgate toothpastes come in numerous varieties, ranging from Colgate Total, Colgate Optic White, and Colgate Tartar Protection to Colgate Sensitive, Colgate Enamel Health, Colgate PreviDent, and Colgate Kids. Then each variety comes in its own special forms and formulations. For example, you can buy Colgate Total in regular, clean mint, advanced whitening, deep clean, total daily repair, 2in1 liquid gel, or any of several other versions.

Finally, the consistency of the product mix refers to how closely related the various product lines are in end use, production requirements, distribution channels, or some other way. Colgate’s product lines are consistent insofar as they are consumer products that go through the same distribution channels. The lines are less consistent insofar as they perform different functions for buyers.

These product mix dimensions provide the handles for defining the company’s product strategy. A company can increase its business in four ways. It can add new product lines, widening its product mix. In this way, its new lines build on the company’s reputation in its other lines. A company can lengthen its existing product lines to become a more full-line company. It can add more versions of each product and thus deepen its product mix. Finally, a company can pursue more product line consistency—or less—depending on whether it wants to have a strong reputation in a single field or in several fields.

From time to time, a company may also have to streamline its product mix to pare out marginally performing lines and to regain its focus. For example, P&G pursues a megabrand strategy built around 23 billion-dollar-plus brands in the household care and beauty and grooming categories. During the past decade, the consumer products giant has sold off dozens of major brands that no longer fit either its evolving focus or the billion-dollar threshold, ranging from Jif peanut butter, Crisco shortening, Folgers coffee, Pringles snack chips, and Sunny Delight drinks to Noxzema skin care products, Right Guard deodorant, Aleve pain reliever, Duracell batteries, CoverGirl and Max Factor cosmetics, Wella and Clairol hair care products, and Iams and other pet food brands. These divestments allow P&G to focus investment and energy on the 70 to 80 core brands that yield 90 percent of its sales and more than 95 percent of profits. “Less [can] be much more,” says P&G’s CEO.19