Channel Behavior and Organization

Distribution channels are more than simple collections of firms tied together by various flows. They are complex behavioral systems in which people and companies interact to accomplish individual, company, and channel goals. Some channel systems consist of only informal interactions among loosely organized firms. Others consist of formal interactions guided by strong organizational structures. Moreover, channel systems do not stand still—new types of intermediaries emerge and whole new channel systems evolve. Here we look at channel behavior and how members organize to do the work of the channel.

Channel Behavior

A marketing channel consists of firms that have partnered for their common good. Each channel member depends on the others. For example, a Ford dealer depends on Ford to design cars that meet customer needs. In turn, Ford depends on the dealer to engage customers, persuade them to buy Ford cars, and service the cars after the sale. Each Ford dealer also depends on other dealers to provide good sales and service that will uphold the brand’s reputation. In fact, the success of individual Ford dealers depends on how well the entire Ford marketing channel competes with the channels of Toyota, GM, Honda, and other auto manufacturers.

Each channel member plays a specialized role in the channel. For example, Samsung’s role is to produce electronics products that consumers will covet and create demand through national advertising. Best Buy’s role is to display these Samsung products in convenient locations, answer buyers’ questions, and complete sales. The channel will be most effective when each member assumes the tasks it can do best.

Ideally, because the success of individual channel members depends on the overall channel’s success, all channel firms should work together smoothly. They should understand and accept their roles, coordinate their activities, and cooperate to attain overall channel goals. However, individual channel members rarely take such a broad view. Cooperating to achieve overall channel goals sometimes means giving up individual company goals. Although channel members depend on one another, they often act alone in their own short-run best interests. They often disagree on who should do what and for what rewards. Such disagreements over goals, roles, and rewards generate channel conflict.

Horizontal conflict occurs among firms at the same level of the channel. For instance, some Ford dealers in Chicago might complain that other dealers in the city steal sales from them by pricing too low or advertising outside their assigned territories. Or Holiday Inn franchisees might complain about other Holiday Inn operators overcharging guests or giving poor service, hurting the overall Holiday Inn image.

Vertical conflict, conflict between different levels of the same channel, is even more common.

![]() For example, McDonald’s has recently faced growing conflict with its corps of 3,100 independent franchisees:2

For example, McDonald’s has recently faced growing conflict with its corps of 3,100 independent franchisees:2

Channel conflict: A high level of franchisee discontent is worrisome to McDonald’s. Franchisees operate more than 90 percent of the chain’s restaurants, and there’s a huge connection between franchisee satisfaction and customer service.

Channel conflict: A high level of franchisee discontent is worrisome to McDonald’s. Franchisees operate more than 90 percent of the chain’s restaurants, and there’s a huge connection between franchisee satisfaction and customer service.

© Greg Balfour Evans/Alamy

Recent surveys of McDonald’s franchise owners have reflected substantial franchisee discontent with the corporation. Some of the conflict has stemmed from a slowdown in system-wide sales in recent years that put both sides on edge. The most basic conflicts are financial. McDonald’s makes its money from franchisee royalties based on total system sales. In contrast, franchisees make money on margins—what’s left over after their costs. To reverse slumping sales, McDonald’s increased its emphasis on aggressive discounting, a strategy that increases corporate sales but squeezes franchisee profits. Franchisees also grumble about adding popular but more complex menu items—such as customizable burgers, McCafe beverages, and all-day breakfasts—that increase the top-line growth for McDonald’s but add preparation, equipment, and staffing costs for franchisees while slowing down service. McDonald’s has also asked franchisees to make costly restaurant upgrades and overhauls. In all, despite recently rebounding sales, franchisees remain disgruntled. The most recent survey rates McDonald’s current franchisee relations at an all-time low 1.81 out of a possible 5, in the “fair” to “poor” range. That’s worrisome for McDonald’s, whose franchise owners operate 90 percent of its locations. Studies show that there’s a huge connection between franchisee satisfaction and customer service.

Some conflict in the channel takes the form of healthy competition. Such competition can be good for the channel; without it, the channel could become passive and noninnovative. For example, the McDonald’s conflict with its franchisees might represent normal give-and-take over the respective rights of the channel partners. However, severe or prolonged conflict can disrupt channel effectiveness and cause lasting harm to channel relationships. McDonald’s should manage the channel conflict carefully to keep it from getting out of hand.

Vertical Marketing Systems

For the channel as a whole to perform well, each channel member’s role must be specified, and channel conflict must be managed. The channel will perform better if it includes a firm, agency, or mechanism that provides leadership and has the power to assign roles and manage conflict.

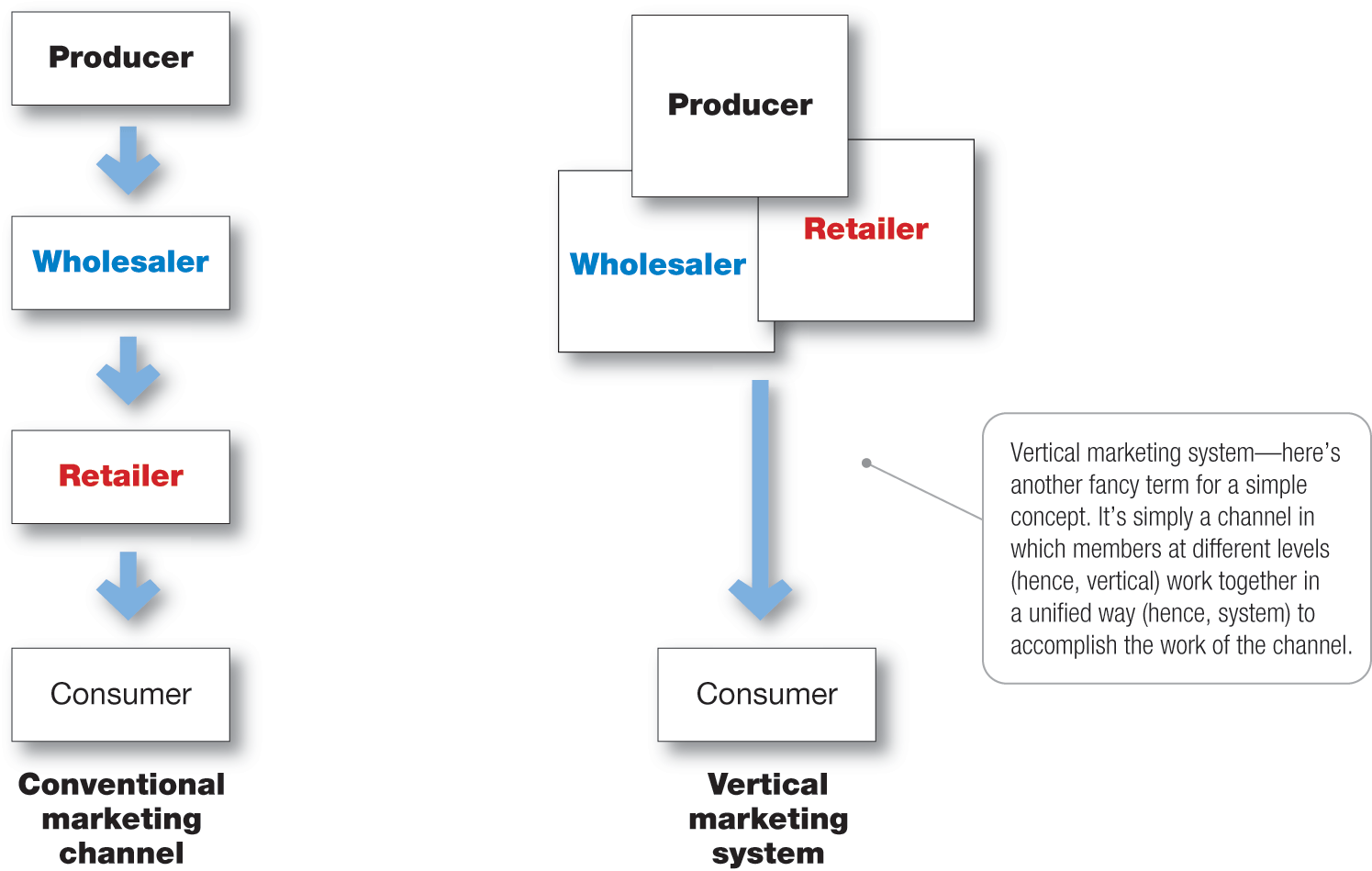

Historically, conventional distribution channels have lacked such leadership and power, often resulting in damaging conflict and poor performance. One of the biggest channel developments over the years has been the emergence of vertical marketing systems that provide channel leadership.

![]() Figure 12.3 contrasts the two types of channel arrangements.

Figure 12.3 contrasts the two types of channel arrangements.

Figure 12.3

Figure 12.3

Comparison of Conventional Distribution Channel with Vertical Marketing System

A conventional distribution channel consists of one or more independent producers, wholesalers, and retailers. Each is a separate business seeking to maximize its own profits, perhaps even at the expense of the system as a whole. No channel member has much control over the other members, and no formal means exists for assigning roles and resolving channel conflict.

In contrast, a vertical marketing system (VMS) consists of producers, wholesalers, and retailers acting as a unified system. One channel member owns the others, has contracts with them, or wields so much power that they must all cooperate. The VMS can be dominated by the producer, the wholesaler, or the retailer.

We look now at three major types of VMSs: corporate, contractual, and administered. Each uses a different means for setting up leadership and power in the channel.

Corporate VMS

A corporate VMS integrates successive stages of production and distribution under single ownership. Coordination and conflict management are attained through regular organizational channels. For example, grocery giant Kroger owns and operates 37 manufacturing plants—17 dairies, 6 bakery plants, 5 grocery plants, 1 deli plant, 2 frozen dough plants, 2 beverage plants, 2 cheese plants, and 2 meat plants. That gives it factory-to-store channel control over 40 percent of the 13,000 private-label items found on its shelves.3

Similarly, little-known Italian eyewear maker Luxottica produces many famous eyewear brands—including its own Ray-Ban, Oakley, Persol, and Vogue Eyewear brands and licensed brands such as Burberry, Chanel, Polo Ralph Lauren, Dolce & Gabbana, DKNY, Prada, Versace, and Michael Kors. Luxottica then controls the distribution of these brands through some of the world’s largest optical chains—LensCrafters, Pearle Vision, Sunglass Hut, Target Optical, Sears Optical—which it also owns. In all, through vertical integration, Luxottica controls an estimated 60 to 80 percent of the U.S. eyewear market.4

Contractual VMS

A contractual VMS consists of independent firms at different levels of production and distribution that join together through contracts to obtain more economies or sales impact than each could achieve alone. Channel members coordinate their activities and manage conflict through contractual agreements.

The franchise organization is the most common type of contractual relationship. In this system, a channel member called a franchisor links several stages in the production-distribution process. In the United States alone, almost 800,000 franchise outlets account for $994 billion of economic output. Industry analysts estimate that a new franchise outlet opens somewhere in the United States every eight minutes and that about one out of every 12 retail business outlets is a franchised business.5

Almost every kind of business has been franchised—from motels and fast-food restaurants to dental centers and dating services, from wedding consultants and handyman services to funeral homes, fitness centers, and moving services.

![]() For example, through franchising, Two Men and a Truck moving services—“Movers Who Care”—grew quickly from two high school students looking to make extra money with a pickup truck to an international network of over 380 franchise locations that’s experienced record growth over the past six years and completed more than 5.5 million moves.6

For example, through franchising, Two Men and a Truck moving services—“Movers Who Care”—grew quickly from two high school students looking to make extra money with a pickup truck to an international network of over 380 franchise locations that’s experienced record growth over the past six years and completed more than 5.5 million moves.6

Franchising systems: Through franchising, Two Men and a Truck—“Movers Who Care”—grew quickly from two high school students with a pickup truck to an international network of over 380 franchise locations that’s experienced record growth over the past six years.

Franchising systems: Through franchising, Two Men and a Truck—“Movers Who Care”—grew quickly from two high school students with a pickup truck to an international network of over 380 franchise locations that’s experienced record growth over the past six years.

Two Men and a Truck International

There are three types of franchises. The first type is the manufacturer-sponsored retailer franchise system—for example, Ford and its network of independent franchised dealers. The second type is the manufacturer-sponsored wholesaler franchise system—Coca-Cola licenses bottlers (wholesalers) in various world markets that buy Coca-Cola syrup concentrate and then bottle and sell the finished product to retailers locally. The third type is the service-firm-sponsored retailer franchise system—for example, Burger King and its more than 12,000 franchisee-operated restaurants around the world. Other examples can be found in everything from auto rentals (Hertz, Avis), apparel retailers (The Athlete’s Foot, Plato’s Closet), and motels (Holiday Inn, Hampton Inn) to supplemental education (Huntington Learning Center, Mathnasium) and personal services (Great Clips, Mr. Handyman, Anytime Fitness).

The fact that most consumers cannot tell the difference between contractual and corporate VMSs shows how successfully the contractual organizations compete with corporate chains. The next chapter presents a fuller discussion of the various contractual VMSs.

Administered VMS

In an administered VMS, leadership is assumed not through common ownership or contractual ties but through the size and power of one or a few dominant channel members. Manufacturers of a top brand can obtain strong trade cooperation and support from resellers. For example, P&G and Apple can command unusual cooperation from many resellers regarding displays, shelf space, promotions, and price policies. In turn, large retailers such as Walmart, Home Depot, Kroger, and Walgreens can exert strong influence on the many manufacturers that supply the products they sell.

For example, in the normal push and pull between Walmart and its consumer goods suppliers, giant Walmart—the biggest grocer in the United States with a more than 25 percent share of all U.S. grocery sales—usually gets its way. Take supplier Clorox, for instance. Although The Clorox Company’s strong consumer brand preference gives it significant negotiating power, Walmart simply holds more cards. Sales to Walmart make up 25 percent of Clorox’s sales, whereas Clorox products account for only one-third of 1 percent of Walmart’s purchases, making Walmart by far the dominant partner. Things get even worse for Cal-Maine Foods and its Eggland’s Best brand, which relies on Walmart for nearly one-third of its sales but tallies only about one-tenth of 1 percent of Walmart’s volume. For such brands, maintaining a strong relationship with the giant retailer is crucial.7

Horizontal Marketing Systems

Another channel development is the horizontal marketing system, in which two or more companies at one level join together to follow a new marketing opportunity. By working together, companies can combine their financial, production, or marketing resources to accomplish more than any one company could alone.

Companies might join forces with competitors or noncompetitors. They might work with each other on a temporary or permanent basis, or they may create a separate company. For example, Walmart partners with noncompetitor McDonald’s to place “express” versions of McDonald’s restaurants in Walmart stores. McDonald’s benefits from Walmart’s heavy store traffic, and Walmart keeps hungry shoppers from needing to go elsewhere to eat.

Horizontal marketing systems: Star Alliance consists of 27 airlines “working in harmony” with shared branding and marketing to smooth and extend each member’s global air travel capabilities.

Horizontal marketing systems: Star Alliance consists of 27 airlines “working in harmony” with shared branding and marketing to smooth and extend each member’s global air travel capabilities.

Felix Gottwald

Horizontal channel arrangements also work well globally.

![]() For example, most of the world’s major airlines have joined to together in one of three global alliances: Star Alliance, Skyteam, or Oneworld. Star Alliance consists of 27 airlines “working in harmony,” including United, Air Canada, Lufthansa, Air China, Turkish Airlines, and almost two dozen others. It offers more than 18,500 combined daily departures to more than 190 destinations around the world. Such alliances tie the individual carriers into massive worldwide air travel networks with joint branding and marketing, co-locations at airports, interline scheduling and smoother global flight connections, and shared rewards and membership privileges.8

For example, most of the world’s major airlines have joined to together in one of three global alliances: Star Alliance, Skyteam, or Oneworld. Star Alliance consists of 27 airlines “working in harmony,” including United, Air Canada, Lufthansa, Air China, Turkish Airlines, and almost two dozen others. It offers more than 18,500 combined daily departures to more than 190 destinations around the world. Such alliances tie the individual carriers into massive worldwide air travel networks with joint branding and marketing, co-locations at airports, interline scheduling and smoother global flight connections, and shared rewards and membership privileges.8

Multichannel Distribution Systems

In the past, many companies used a single channel to sell to a single market or market segment. Today, with the proliferation of customer segments and channel possibilities, more and more companies have adopted multichannel distribution systems. Such multichannel marketing occurs when a single firm sets up two or more marketing channels to reach one or more customer segments.

![]() Figure 12.4 shows a multichannel marketing system. In the figure, the producer sells directly to consumer segment 1 using catalogs, online, and mobile channels and reaches consumer segment 2 through retailers. It sells indirectly to business segment 1 through distributors and dealers and to business segment 2 through its own sales force.

Figure 12.4 shows a multichannel marketing system. In the figure, the producer sells directly to consumer segment 1 using catalogs, online, and mobile channels and reaches consumer segment 2 through retailers. It sells indirectly to business segment 1 through distributors and dealers and to business segment 2 through its own sales force.

Figure 12.4

Figure 12.4

Multichannel Distribution System

These days, almost every large company and many small ones distribute through multiple channels. For example, John Deere sells its familiar green-and-yellow lawn and garden tractors, mowers, and outdoor power products to consumers and commercial users through several channels, including John Deere retailers, Lowe’s home improvement stores, and online. It sells and services its tractors, combines, planters, and other agricultural equipment through its premium John Deere dealer network. And it sells large construction and forestry equipment through selected large, full-service John Deere dealers and their sales forces.

Multichannel distribution systems offer many advantages to companies facing large and complex markets. With each new channel, the company expands its sales and market coverage and gains opportunities to tailor its products and services to the specific needs of diverse customer segments. But such multichannel systems are harder to control, and they can generate conflict as more channels compete for customers and sales. For example, when John Deere first began selling selected consumer products through Lowe’s home improvement stores, many of its independent dealers complained loudly. To avoid such conflicts in its online marketing channels, the company routes all of its online sales to John Deere dealers.

Changing Channel Organization

Changes in technology and the explosive growth of direct and online marketing are having a profound impact on the nature and design of marketing channels. One major trend is toward disintermediation—a big term with a clear message and important consequences. Disintermediation occurs when product or service producers cut out intermediaries and go directly to final buyers or when radically new types of channel intermediaries displace traditional ones.

Thus, in many industries, traditional intermediaries are dropping by the wayside, as is the case with online marketers taking business from traditional brick-and-mortar retailers. For example, online music download services such as iTunes and Amazon MP3 have pretty much put traditional music-store retailers out of business, with physical CDs sinking fast and now capturing less than a third of the music market.

![]() In turn, however, streaming music services such as Spotify, Rhapsody, and Apple Music are now disintermediating digital download services—digital downloads peaked last year while music streaming increased 29 percent.9

In turn, however, streaming music services such as Spotify, Rhapsody, and Apple Music are now disintermediating digital download services—digital downloads peaked last year while music streaming increased 29 percent.9

Disintermediation: Streaming music services such as Spotify are rapidly disintermediating both traditional music-store retailers and even music download services such as iTunes.

Disintermediation: Streaming music services such as Spotify are rapidly disintermediating both traditional music-store retailers and even music download services such as iTunes.

© DADO RUVIC/Reuters/Corbis

Disintermediation presents both opportunities and problems for producers and resellers. Channel innovators who find new ways to add value in the channel can displace traditional resellers and reap the rewards. In turn, traditional intermediaries must continue to innovate to avoid being swept aside. For example, when Netflix pioneered online DVD-by-mail video rentals, it sent traditional brick-and-mortar video stores such as Blockbuster into ruin. Then Netflix itself faced disintermediation threats from an even hotter channel—video streaming. But instead of simply watching developments, Netflix has led them profitably (see Real Marketing 12.1).

Similarly, superstore booksellers Barnes & Noble and Borders pioneered huge book selections and low prices, shutting down most small independent bookstores. Then along came Amazon.com, which threatened even the largest brick-and-mortar bookstores. Amazon.com almost single-handedly bankrupted Borders in less than 10 years. Now, both offline and online sellers of physical books are being threatened by digital book downloads and e-readers. Rather than yielding to digital developments, however, Amazon.com is leading them with its highly successful Kindle e-readers and tablets. By contrast, Barnes & Noble—the giant that put so many independent bookstores out of business—was a latecomer with its struggling Nook e-reader and now finds itself locked in a battle for survival.10

Like resellers, to remain competitive, product and service producers must develop new channel opportunities, such as the internet and other direct channels. However, developing these new channels often brings them into direct competition with their established channels, resulting in conflict. To ease this problem, companies often look for ways to make going direct a plus for the entire channel.

For example, Volvo Car Group (now owned by Chinese car maker Geeley) recently announced plans to start selling Volvo vehicles online in all of its markets. Some 80 percent of Volvo buyers already shop online for other goods, so cars seem like a natural extension. Few auto makers have tried selling directly, with the exception of Tesla, which sells its all-electric cars online, bypassing dealers altogether. Other car companies worry that selling directly would alienate their independent dealer networks. “If you say e-commerce, initially dealers get nervous,” says Volvo’s head of marketing. So, to avoid channel conflicts, Volvo will pass all online sales through established dealers for delivery. In that way, boosting sales through direct marketing will benefit both Volvo and its channel partners.11