Retailer Marketing Decisions

Retailers are always searching for new marketing strategies to attract and hold customers. In the past, retailers attracted customers with unique product assortments and more or better services. Today, the assortments and services of various retailers are looking more and more alike. You can find most consumer brands not only in department stores but also in mass-merchandise discount stores, off-price discount stores, and all over the internet. Thus, it’s now more difficult for any one retailer to offer exclusive merchandise.

Service differentiation among retailers has also eroded. Many department stores have trimmed their services, whereas discounters have increased theirs. In addition, customers have become smarter and more price sensitive. They see no reason to pay more for identical brands, especially when service differences are shrinking. For all these reasons, many retailers today are rethinking their marketing strategies.

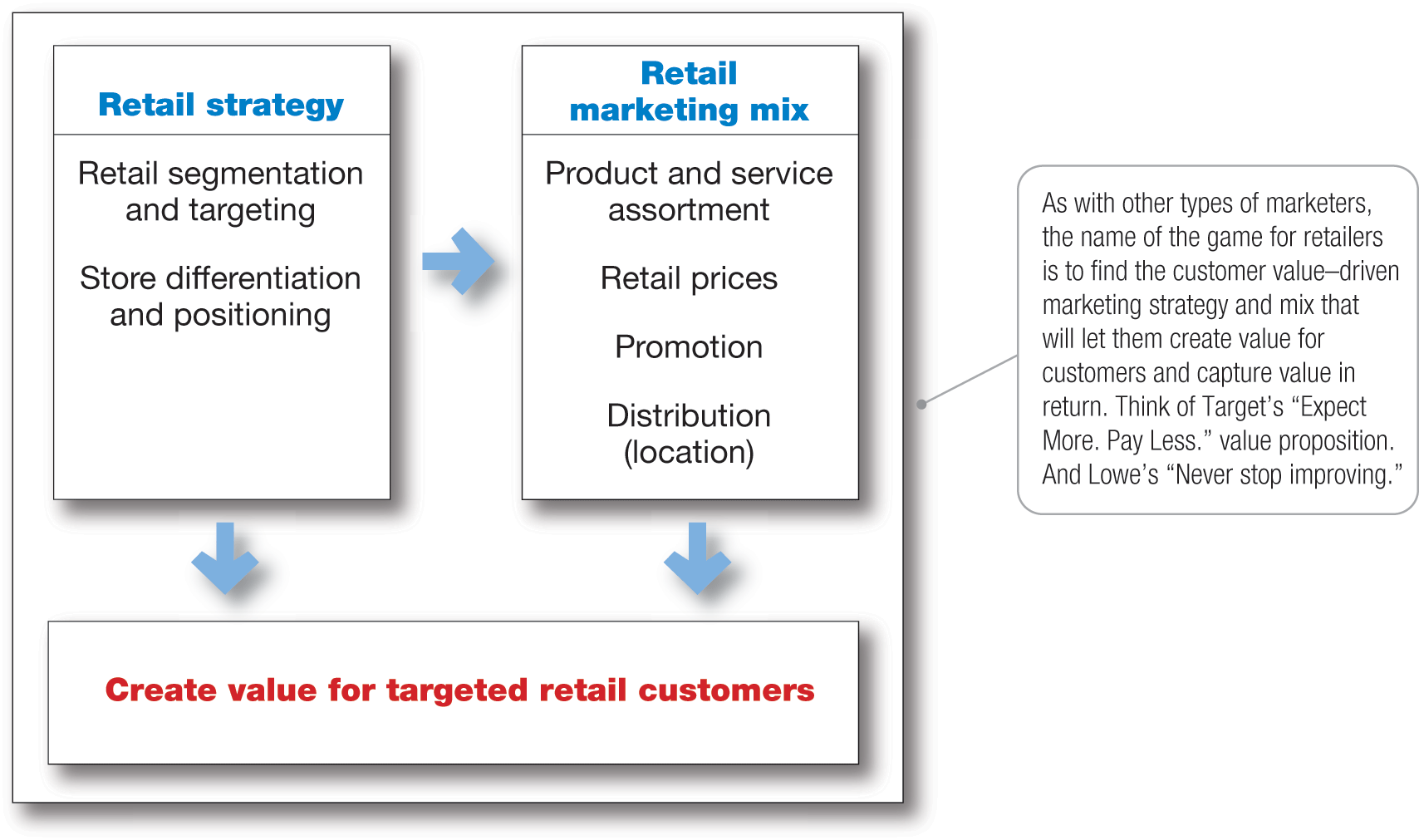

As shown in

![]() Figure 13.1, retailers face major marketing decisions about segmentation and targeting, store differentiation and positioning, and the retail marketing mix.

Figure 13.1, retailers face major marketing decisions about segmentation and targeting, store differentiation and positioning, and the retail marketing mix.

Figure 13.1

Figure 13.1

Retailer Marketing Strategies

Segmentation, Targeting, Differentiation, and Positioning Decisions

Retailers must first segment and define their target markets and then decide how they will differentiate and position themselves in these markets. Should they focus on upscale, midscale, or downscale shoppers? Do target shoppers want variety, depth of assortment, convenience, or low prices? Until they define and profile their markets, retailers cannot make consistent decisions about product assortment, services, pricing, advertising, store décor, online and mobile site design, or any of the other decisions that must support their positions.

Too many retailers, even big ones, fail to clearly define their target markets and positions. For example, what market does clothing chain Gap target? What is Gap’s value proposition? If you’re having trouble answering those questions, you’re not alone—so is Gap’s management.14

In its heyday, Gap was solidly positioned on “effortless cool”—the then-fashionable preppy look focused on comfortable, casual clothes and easy shopping. But as its core Generation X customers aged and moved on, Gap stores didn’t. Moving into the 2000s, Gap catered to short-lived fashion trends that alienated its loyal customer base. At the same time, it has struggled unsuccessfully to define new positioning that works with today’s younger shoppers. And more-contemporary fast-fashion retailers such as H&M, Forever 21, Zara, and Uniqlo have moved in aggressively on Gap’s turf. Whereas these brands are clearly targeted and positioned, Gap’s identity has become muddled. As a result, the chain’s sales have flattened for fallen off, and last year it closed 175 of its 675 North American stores. “Neither they nor their consumer know exactly who they are targeting,” says one retail analyst. Gap “hasn’t got a story,” says another. Is it “trying to sell to my wife or my teenage daughter or both? I don’t think you can do both.” To rekindle the brand, Gap needs to “define who the brand’s core customers are and be exceptional to them.”

By contrast, successful retailers define their target markets well and position themselves strongly. For example, Trader Joe’s has established its “cheap gourmet” value proposition. Walmart is powerfully positioned on low prices and what those always-low prices mean to its customers. And highly successful outdoor products retailer Bass Pro Shops positions itself strongly as being “as close to the Great Outdoors as you can get indoors!”

Retail targeting and positioning: In-N-Out Burger thrives by positioning itself away from McDonald’s. The chain stays with what it does best: making really good hamburgers, really good fries, and really good shakes—that’s it.

Retail targeting and positioning: In-N-Out Burger thrives by positioning itself away from McDonald’s. The chain stays with what it does best: making really good hamburgers, really good fries, and really good shakes—that’s it.

© E.J. Baumeister Jr. / Alamy

With solid targeting and positioning, a retailer can compete effectively against even the largest and strongest competitors.

![]() For example, compare small In-N-Out Burger to giant McDonald’s. In-N-Out now has only about 300 stores in five states, with estimated sales of $750 million. McDonald’s has 36,000 stores in more than 100 countries, racking up more than $98 billion of annual system-wide sales. How does In-N-Out compete with the world’s largest fast-food chain? It doesn’t—at least not directly. In-N-Out succeeds by carefully positioning itself away from McDonald’s:15

For example, compare small In-N-Out Burger to giant McDonald’s. In-N-Out now has only about 300 stores in five states, with estimated sales of $750 million. McDonald’s has 36,000 stores in more than 100 countries, racking up more than $98 billion of annual system-wide sales. How does In-N-Out compete with the world’s largest fast-food chain? It doesn’t—at least not directly. In-N-Out succeeds by carefully positioning itself away from McDonald’s:15

In-N-Out has never wanted to be like McDonald’s, growing rapidly and expanding both its menu and locations. Instead, In-N-Out thrives by doing the unthinkable: growing slowly and not changing. From the start, In-N-Out’s slogan has been, “Quality you can taste.” Burgers are made from 100 percent pure beef—no additives, fillers, or preservatives—and they’re always fresh, not frozen. Fries are made from whole potatoes, and, yes, milkshakes are made from real ice cream. You won’t find a freezer, heating lamp, or microwave oven in an In-N-Out restaurant. And unlike McDonald’s unending stream of new menu items, In-N-Out stays with what the chain has always done well: making really good hamburgers, really good fries, and really good shakes—that’s it.

Moreover, far from standardized fare, In-N-Out gladly customizes any menu item. Menu modifications have become so common at In-N-Out that a “secret” ordering code has emerged that isn’t posted on menu boards. Customers in the know can order their burgers “animal style” (pickles, extra spread, grilled onions, and a mustard-fried patty). And whereas the “Double-Double” (double meat, double cheese) is on the menu, burgers can also be ordered Fries can also be ordered animal style (two slices of cheese, grilled onions, and spread), well-done, or light. This secret menu makes customers feel special. Another thing that makes them feel special is In-N-Out’s outgoing, enthusiastic, and capable employees who deliver unexpectedly friendly service. You won’t find that at McDonald’s. Finally, in contrast to McDonald’s obsession to grow, grow, grow; In-N-Out’s slow-and-steady growth means that you won’t find one on every corner. The scarcity of In-N-Out stores only adds to its allure. Customers regularly go out of their way and drive long distances to get their In-N-Out fix.

So, In-N-Out can’t match McDonald’s massive economies of scale, incredible volume purchasing power, ultra-efficient logistics, and low prices. Then again, it doesn’t even try. By positioning itself away from McDonald’s and other large competitors, In-N-Out has developed a cult-like following. When it comes to customer satisfaction, In-N-Out regularly posts the highest customer satisfaction scores of any fast-food restaurant in its markets. Long lines snake out the door of any location at lunchtime and In-N-Out’s average per-store sales are double the industry average.

Product Assortment and Services Decision

Retailers must decide on three major product variables: product assortment, services mix, and store atmosphere.

The retailer’s product assortment should differentiate it while matching target shoppers’ expectations. One strategy is to offer a highly targeted product assortment: Lane Bryant carries plus-size clothing, Brookstone offers an unusual assortment of gadgets and gifts, and BatteryDepot.com offers about every imaginable kind of replacement battery. Alternatively, a retailer can differentiate itself by offering merchandise that no other competitor carries, such as store brands or national brands on which it holds exclusive rights. For example, Kohl’s gets exclusive rights to carry well-known labels such as Simply Vera by Vera Wang and a Food Network-branded line of kitchen tools, utensils, and appliances. Kohl’s also offers its own private-label lines, such as Sonoma, Croft & Barrow, Candies, and Apt. 9.

The services mix can also help set one retailer apart from another. For example, some retailers invite customers to ask questions or consult service representatives in person or via phone or tablet. Home Depot offers a diverse mix of services to do-it-yourselfers, from “how-to” classes and “do-it-herself” and kid workshops to a proprietary credit card. Nordstrom delivers top-notch service and promises to “take care of the customer, no matter what it takes.”

The store’s atmosphere is another important element in the reseller’s product arsenal. Retailers want to create a unique store experience, one that suits the target market and moves customers to buy. Many retailers practice experiential retailing. For example, L.L.Bean has turned its flagship Freeport store and campus into a full-fledged outdoor adventure center, where customers can hike, bike, golf, kayak, or even go seal watching or fishing at nearby Cisco Bay. Along with selling outdoor apparel and gear, L.L.Bean offers a slate of free in-store, hands-on clinics along with Outdoor Discovery Schools programs in snowshoeing, cross-country skiing, stand-up paddleboarding, fly fishing, biking, birdwatching, canoeing, hunting, or any of a dozen other outdoor activities.

![]() Similarly, up-scale home furnishings retailer Restoration Hardware has unleashed a new generation of furniture galleries in Chicago, Atlanta, Denver, Tampa, and Hollywood that are part store, part interior design studio, part restaurant, and part home:16

Similarly, up-scale home furnishings retailer Restoration Hardware has unleashed a new generation of furniture galleries in Chicago, Atlanta, Denver, Tampa, and Hollywood that are part store, part interior design studio, part restaurant, and part home:16

Experiential retailing: Furnishings retailer Restoration Hardware has unleashed a new generation of furniture galleries that are part store, part interior design studio, and part restaurant. In these new stores, you don’t just see the furnishings, you experience them.

Experiential retailing: Furnishings retailer Restoration Hardware has unleashed a new generation of furniture galleries that are part store, part interior design studio, and part restaurant. In these new stores, you don’t just see the furnishings, you experience them.

Mike Dupre / Stringer / Getty Images

Picture this: You’re sipping a glass of good wine, surrounded by plush furnishings and crystal chandeliers with soothing music playing in the background. You’re not sure whether to order another glass of wine, a light lunch, or both. Instead, you decide to buy the furniture you’re upon which you are sitting. You’re not in a fancy restaurant; you’re in RH Chicago, a new retail concept by Restoration Hardware. Most retail furniture stores do little more than display their wares in functional fashion. Not so at RH galleries. “We wanted to blur the lines between residential and retail, and create a sense of place that is more home than store,” says Restoration Hardware’s CEO. The RH Atlanta gallery is a massive 70,000-square-foot, six-story estate on two acres, complete with a 40-foot-tall entry rotunda flanked by a double staircase, gardens, terraces, a 50-foot-long reflecting pool, and a rooftop park. Its rooms and outdoor places serve as showrooms for the goods that Restoration Hardware sells, from glasses to furniture to rugs to items for the garden. But it feels more like a grand home. You don’t just see the furnishings, you experience them. “We created spaces where guests who visit our new homes are saying ‘I want to live here,’” says the CEO. “I’ve been in retail almost 40 years and I’ve never heard anyone say they wanted to live in a retail store, until now.”

Successful retailers carefully orchestrate virtually every aspect of the consumer store experience. The next time you step into a retail store—whether it sells consumer electronics, hardware, food, or high fashion—stop and carefully consider your surroundings. Think about the store’s layout and displays. Listen to the background music. Check out the colors. Smell the smells. Chances are good that everything in the store, from the layout and lighting to the music and even the colors and smells, has been carefully orchestrated to help shape the customers’ shopping experiences—and open their wallets.

For example, retailers choose the colors in their logos and interiors carefully: Black suggests sophistication, orange is associated with fairness and affordability, white signifies simplicity and purity (think Apple stores), and blue connotes trust and dependability (financial institutions use it a lot). And most large retailers have developed signature scents that you smell only in their stores:17

Anytime Fitness pipes in “Inspire,” a eucalyptus-mint fragrance to create a uniform scent from store to store and mask that “gym” smell. Bloomingdale’s uses different essences in different departments: the soft scent of baby powder in the baby store, coconut in the swimsuit area, lilacs in intimate apparel, and sugar cookies and evergreen scent during the holiday season. Luxury men’s fashion brand Hugo Boss chose a signature smooth, musky scent for all of its stores. “We wanted it to feel like coming home,” says a Hugo Boss marketer. Scents can subtly reinforce a brand’s imagery and positioning. For example, the Hard Rock Café Hotel in Orlando added a scent of the ocean in its lobby to help guests imagine checking into a seaside resort (even though the hotel is located an hour from the coast). To draw customers into the hotel’s often-overlooked downstairs ice cream shop, the hotel put a sugar cookie aroma at the top of the stairs and a whiff of waffle cone at the bottom. Ice cream sales jumped 45 percent in the following six months.

Such experiential retailing confirms that retail stores are much more than simply assortments of goods. They are environments to be experienced by the people who shop in them.

Price Decision

A retailer’s price policy must fit its target market and positioning, product and service assortment, the competition, and economic factors. All retailers would like to charge high markups and achieve high volume, but the two seldom go together. Most retailers seek either high markups on lower volume (most specialty stores) or low markups on higher volume (mass merchandisers and discount stores).

Thus, 110-year-old Bergdorf Goodman caters to the upper crust by selling apparel, shoes, and jewelry created by designers such as Chanel, Prada, Hermes, and Jimmy Choo. The upmarket retailer pampers its customers with services such as a personal shopper and in-store showings of the upcoming season’s trends with cocktails and hors d’oeuvres. By contrast, TJ Maxx sells brand name clothing at discount prices aimed at middle-class Americans. As it stocks new products each week, the discounter provides a treasure hunt for bargain shoppers. “No sales. No gimmicks.” says the retailer. “Just brand name and designer fashions for you . . . for up to 60 percent off department store prices.”

Retailers must also decide on the extent to which they will use sales and other price promotions. Some retailers use no price promotions at all, competing instead on product and service quality rather than on price. For example, it’s difficult to imagine Bergdorf Goodman holding a two-for-the-price-of-one sale on Chanel handbags, even in a tight economy. Other retailers—such as Walmart, Costco, ALDI, and Family Dollar—practice everyday low pricing (EDLP), charging constant, everyday low prices with few sales or discounts.

Still other retailers practice high-low pricing—charging higher prices on an everyday basis coupled with frequent sales and other price promotions to increase store traffic, create a low-price image, or attract customers who will buy other goods at full prices. Recent tighter economic times caused a rash of high-low pricing, as retailers poured on price cuts and promotions to coax bargain-hunting customers into their stores. Which pricing strategy is best depends on the retailer’s overall marketing strategy, the pricing approaches of its competitors, and the economic environment.

Promotion Decision

Retailers use various combinations of the five promotion tools—advertising, personal selling, sales promotion, public relations, and direct and social media marketing—to reach consumers. They advertise in newspapers and magazines and on radio and television. Advertising may be supported by newspaper inserts and catalogs. Store salespeople greet customers, meet their needs, and build relationships. Sales promotions may include in-store demonstrations, displays, sales, and loyalty programs. PR activities, such as new-store openings, special events, newsletters and blogs, store magazines, and public service activities, are also available to retailers.

Most retailers also interact digitally with customers using websites and digital catalogs, online ads and video, social media, mobile ads and apps, blogs, and email. Almost every retailer, large or small, maintains a full social media presence. For example, giant Walmart leads the way with a whopping 33 million Facebook Likes, 66,000 Pinterest followers, 754,000 Twitter followers, and 109,000 YouTube subscribers. By contrast, Fairway Market, the small but fast-growing metropolitan New York grocery chain that carries a huge product assortment—from “sky-high piles” of produce to overflowing bins of fresh seafood to hand-roasted coffee—has only 118,000 Facebook Likes. But Fairway isn’t complaining—that’s twice as many Facebook Likes per million dollars of sales as mighty Walmart.18

Retailer promotion: Most retailers interact digitally with customers using websites and digital catalogs, mobile and social media, and other digital platforms. CVS’s myWeekly Ad program distributes personalized versions of its weekly circulars to the chain’s ExtraCare loyalty program members.

Retailer promotion: Most retailers interact digitally with customers using websites and digital catalogs, mobile and social media, and other digital platforms. CVS’s myWeekly Ad program distributes personalized versions of its weekly circulars to the chain’s ExtraCare loyalty program members.

CVS Health

Digital promotions let retailers reach individual customers with carefully targeted messages. For example, to compete more effectively against rivals online, CVS distributes personalized versions of its weekly circulars to the chain’s ExtraCare loyalty program members.

![]() Called myWeekly Ad, customers can view their circulars by logging into their personal accounts at CVS.com on computers, tablets, or smartphones. Based on ExtraCare members’ characteristics and previous purchases, the personalized promotions highlight sales items and special offers of special interest to each specific customer. With the myWeekly Ad program, “We’re trying to get people to change their behavior,” says the CVS marketer heading up the effort, “going online for a much more personalized experience” rather than checking weekly circulars.19

Called myWeekly Ad, customers can view their circulars by logging into their personal accounts at CVS.com on computers, tablets, or smartphones. Based on ExtraCare members’ characteristics and previous purchases, the personalized promotions highlight sales items and special offers of special interest to each specific customer. With the myWeekly Ad program, “We’re trying to get people to change their behavior,” says the CVS marketer heading up the effort, “going online for a much more personalized experience” rather than checking weekly circulars.19

Place Decision

Retailers often point to three critical factors in retailing success: location, location, and location! It’s very important that retailers select locations that are accessible to the target market in areas that are consistent with the retailer’s positioning. For example, Apple locates its stores in high-end malls and trendy shopping districts—such as the Magnificent Mile on Chicago’s Michigan Avenue or Fifth Avenue in Manhattan—not low-rent strip malls on the edge of town. By contrast, to keep costs down and support its “cheap gourmet” positioning, Trader Joe’s places its stores in lower-rent, out-of-the-way locations. Small retailers may have to settle for whatever locations they can find or afford. Large retailers, however, usually employ specialists who use advanced methods to select store locations.

Most stores today cluster together to increase their customer pulling power and give consumers the convenience of one-stop shopping. Central business districts were the main form of retail cluster until the 1950s. Every large city and town had a central business district with department stores, specialty stores, banks, and movie theaters. When people began moving to the suburbs, however, many of these central business districts, with their traffic, parking, and crime problems, began to lose business. In recent years, many cities have joined with merchants to revive downtown shopping areas, generally with only mixed success.

A shopping center is a group of retail businesses built on a site that is planned, developed, owned, and managed as a unit. A regional shopping center, or regional shopping mall, the largest and most dramatic shopping center, has from 50 to more than 100 stores, including two or more full-line department stores. It is like a covered mini-downtown and attracts customers from a wide area. A community shopping center contains between 15 and 50 retail stores. It normally contains a branch of a department store or variety store, a supermarket, specialty stores, professional offices, and sometimes a bank. Most shopping centers are neighborhood shopping centers or strip malls that generally contain between 5 and 15 stores. These centers, which are close and convenient for consumers, usually contain a supermarket, perhaps a discount store, and several service stores—dry cleaner, drugstore, hardware store, local restaurant, or other stores.20

A newer form of shopping center is the so-called power center. Power centers are huge unenclosed shopping centers consisting of a long strip of retail stores, including large, freestanding anchors such as Walmart, Home Depot, Costco, Best Buy, Michaels, PetSmart, and Office Depot. Each store has its own entrance with parking directly in front for shoppers who wish to visit only one store.

In contrast, lifestyle centers are smaller, open-air malls with upscale stores, convenient locations, and nonretail activities, such as a playground, skating rink, hotel, dining establishments, and a movie theater complex. The most recent lifestyle centers often consist of mixed-use developments, with ground-floor retail establishments and apartments or condominiums above, combining shopping convenience with the community feel of a neighborhood center. Meanwhile, traditional regional shopping malls are adding lifestyle elements—such as fitness centers, children’s play areas, common areas, and multiplex theaters—to make themselves more social and welcoming. In all, today’s centers are more like places to hang out rather than just places to shop.

The past few years have brought hard times for shopping centers. Many experts suggest that the country has long been “overmalled.” Not surprisingly, the Great Recession and its aftermath hit shopping malls hard. Consumer spending cutbacks forced many retailers—small and large—out of business, and vacancy rates at the nation’s enclosed malls soared.21 Power centers were also hard hit as their big-box retailer tenants such as Circuit City, Borders, Mervyns, and Linens N Things went out of business and others such as Best Buy, Barnes & Noble, and Office Depot reduced the number or size of their stores. Some of the pizzazz has also gone out of lifestyle centers, whose upper-middle-class shoppers suffered most during the recession.

As the economy has improved, however, malls of all types have rebounded a bit. Many power centers, for example, are filling their empty space with a broader range of retailers, from the likes of Ross Dress for Less, Boot Barn, Nordstrom Rack, and other off-price retailers to dollar stores, warehouse grocers, and traditional discounters like Walmart and Target.