Online communities have been around for decades, but it took recent advances in usability, widespread Internet adoption, and the proliferation of social media to make online communities and social networks something organizations could no longer afford to ignore.

The Internet on which the Web runs is a communications platform. Long before the Web, nerds with common interests found ways to talk amongst themselves. In fact, people using computers started to connect with each other during the early 1960s. Even before the Internet was introduced, military organizations and large corporations were implementing ambitious networks to share and store information.

By the 1970s, bulk email platforms kept groups in touch using listservs. These special-interest mailing lists are still widely used today in the form of Google Groups, Yahoo! Groups, and MSN Groups. Some community platforms also emerged in academic environments, running on university minicomputers.

Bulletin board systems (BBSs) brought computer-based communities out of academia and into the public psyche. In 1978, Ward Christensen—snowed in and bored during a storm in Chicago—decided to write the first BBS, known simply as CBBS.

In the world of amateur technologists, BBSs were an instant hit. Fueled by the popularity and affordability of the personal computer, thousands of hobbyists began building and operating their own. They all featured the same basic functions:

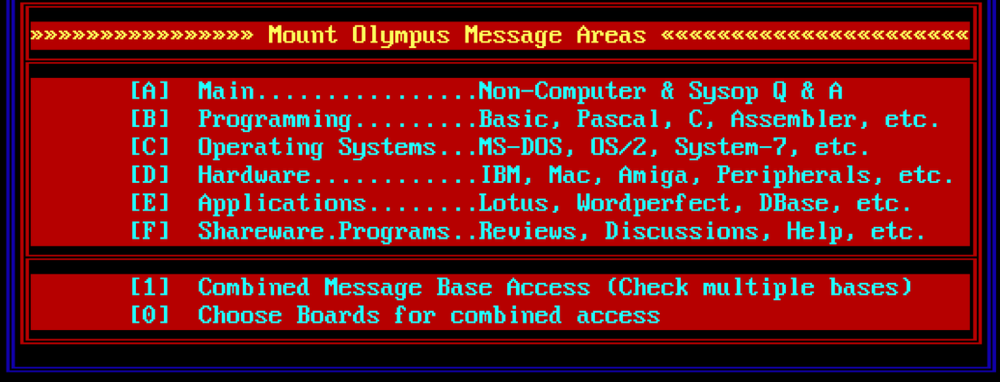

A message base that allowed users to communicate with each other locally or regionally (through inter-BBS protocols such as FidoNet)

A file sharing system that allowed users to upload and download files

Turn-based and real-time “door” games that allowed users to compete against each other

Real-time chat, allowing users to converse with one another

Early BBSs often included other functions such as voting, BBS lists, polls, and art galleries (Figure 11-2) that helped personalize them and increased visitor stickiness. BBSs became popular enough that people traveled from various countries to meet each other in person. They foreshadowed the modern Web—in fact, nearly everything that’s happened on the Web has happened before in the BBS world on a far smaller and geekier scale.

A dominant feature of BBSs was a message base like the one shown in Figure 11-3. This was a forum that allowed users to interact with one another, typically organized around a topic or special-interest group. Some of these areas were private, hidden to other users if they didn’t have the required credentials.

Some BBS communities are still strong today—the Whole Earth ’Lectronic Link (WELL) was founded in 1985, but made the transition to the Web and is still around (as part of Salon.com). Until relatively recently, however, online communities were the domain of technologists, activists, and fringe groups. Widespread adoption of computers with Internet access wasn’t enough for communities to become truly mainstream. They also had to be easy to use.

To use an early BBS, visitors had to type cryptic modem codes into terminals, often dialing for hours to try to get through to perpetually busy phone lines. Then they stared at text-only screens and slow-moving cursors. It wasn’t an easy way to connect with others, and it attracted a certain kind of user.

Despite the efforts of communities in the 1980s that built client-side graphical mouse-driven interfaces, these systems were generally proprietary, platform-specific approaches that discouraged widespread adoption, for example, Hi_Res BBS, Magic BBS, and COCONET (http://www.bbsdocumentary.com/software/IBM/DOS/COCONET/). Accounts were also tied to the individual BBS—if you frequented 10 different BBSs, you had 10 different email messages to check, which made it hard to centralize your online identity.

Today, users don’t need special hardware or lengthy codes—they just need a web browser. Online communities of many different types welcome everyone. But at their core, communities haven’t changed much at all: they exist for interaction. In the end, online communities are about the conversation.