With so many free web platforms now available, it’s easy to craft a message and build grassroots support, provided you can generate genuine attention from an audience. Getting genuine attention is the hard part.

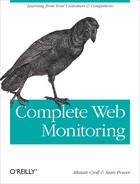

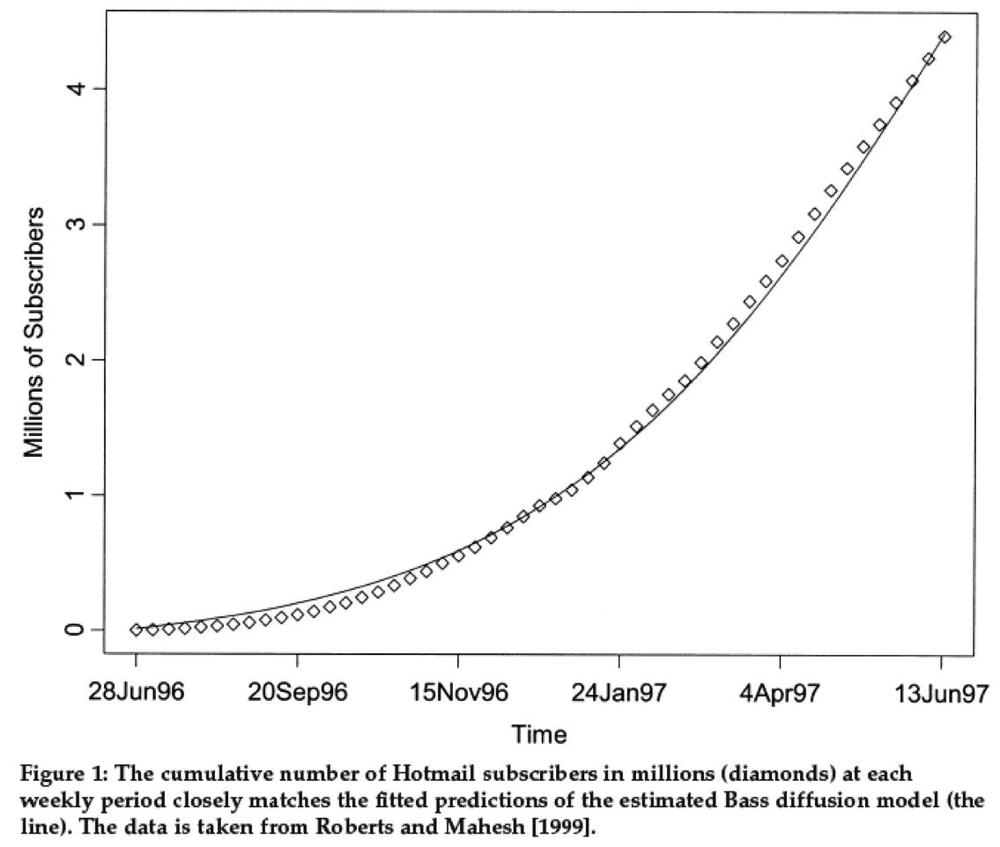

In an industry once dominated by one-to-many broadcasting, online marketing analytics brought accountability to advertising. Viral marketing approaches made it easy to spread messages. And now community marketing—done right—makes it possible to overcome the natural skepticism of a media-saturated audience and communicate with it directly. Figure 12-2 shows how information flows in each of these models.

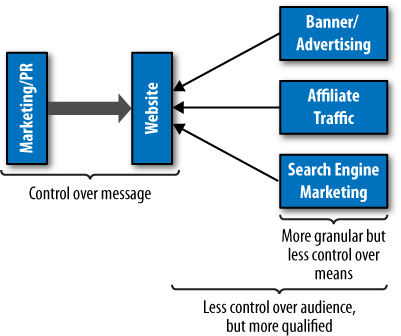

Figure 12-2. How messages flow between buyers and sellers in various marketing communications approaches

Broadcast marketing was the twentieth century’s dominant form of promotion. It cost money to design and produce a message, and still more money to print and ship it, or to license some spectrum and transmit it. Broadcasting a single message to a broad audience offered the economies of scale needed to market cost-effectively. Where the industrial revolution gave us mass production, broadcast marketing gave us mass media.

Computerization and lower production costs meant that advertisers could target their messages to specific audiences according to publication, TV program, or geography—with computers, the incremental cost of a personal message was nearly zero. Marketers used databases and form letters to try to optimize which prospects received which messages. But while they were tailored to some degree, those messages were tightly controlled.

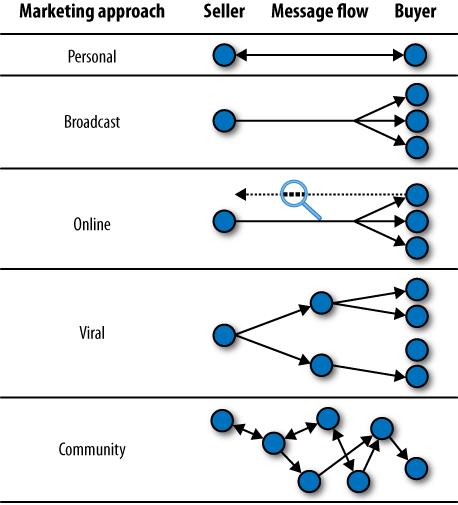

In the traditional marketing communication model shown in Figure 12-3, the marketing team creates a message that combines the interests of the product team, legal and ethical restrictions, and the company’s brand and overall positioning. The message is then distributed through mass media, public relations, and other channels. The audience is segmented, but largely unqualified. In broadcast marketing, that’s OK: volume trumps precision. The more people you reach, the larger the response.

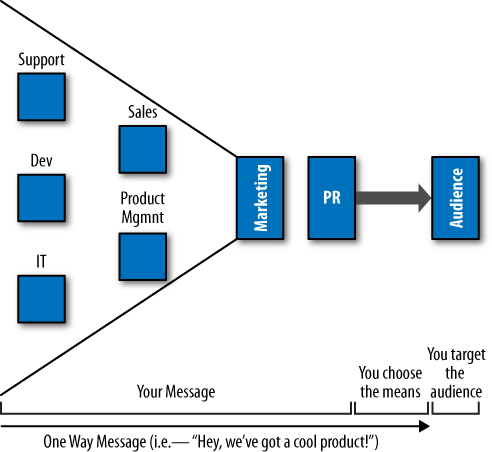

Unfortunately, broadcast audiences are nearing saturation. The average American sees a tremendous amount of advertising, as shown in Figure 12-4: 245 ad exposures daily, of which 108 come from television, 34 from radio, and 112 from print (these are AMIC.com estimates—some of the most conservative). And that’s just the ads they notice—some estimates claim that they’re exposed to thousands a day.

It’s not just saturation that’s killing traditional marketing. People are also ignoring the messages. They tune out promotions, skipping them with their Tivo. TV producers have switched to product placement as the world skips past paid advertising. 30 Rock runs an episode mocking demand for product placement, and in doing so, showcases a product. Tina Fey looks straight at the camera, winks, and says, “Can we have our money now?” Even the great Stephen Colbert tells his Nation to eat Doritos as part of the show itself.

Broadcast audiences are both weary and wary. Ad revenues are in free-fall, and newspapers are foundering. The broadcast era is waning, not only because people are saturated and bored with its impersonal content, but because the precise tracking that’s possible with online campaigns makes broadcast media look like a blunt instrument. It’s unaccountable, unwieldy, and overpriced, and advertisers are switching to other approaches.

With online marketing, advertisers see the results of their efforts. Outcomes are tightly tied to campaigns, making online approaches a much more attractive resource for getting a message out.

Online marketing can be better targeted, too. Through careful segmentation along dimensions such as geography, gender, age, or keyword, there’s a much higher chance that a message will resonate with its recipient, turning a prospect into a convert. And those messages can be adjusted over time, mid-campaign, to maximize their effectiveness.

In the online marketing model, advertisers still control the message, although it might take the form of teaser ads, search results, affiliate referrals, or paid content. They can also choose their target segments, but they have much less control over the distribution of the message—they’ve outsourced that part of the work to the other online properties instead. Figure 12-5 shows how online marketing works.

Online marketing is still paid marketing. Ad dollars are tracked for effectiveness to provide accountability, and to let advertisers optimize their spending. It also has two fundamental problems:

First, a message only goes as far as it’s paid to. It’s not amplified by the audience. To reach more people efficiently, advertisers need a communications model that scales well, growing by itself rather than costing them more money to reach more people.

Second, the audience still largely ignores the message because it’s untrusted. Ads are noise, and with the notable exception of relevance-based advertising, like paid search, people mostly ignore them.

One technique, viral marketing, addresses the first challenge by letting the audience itself amplify the message.

The term viral marketing was coined by Jeffrey Rayport in 1996. It describes a form of marketing that’s designed to be repeated. Borrowing from concepts within epidemiology, viral marketing “infects” the audience, encouraging those who hear the message to amplify it. Done right, it’s a much more efficient way to garner attention, it’s cheaper to deliver, and it enjoys demand-side economies of scale. That is, the volume of the message grows as more people hear it.

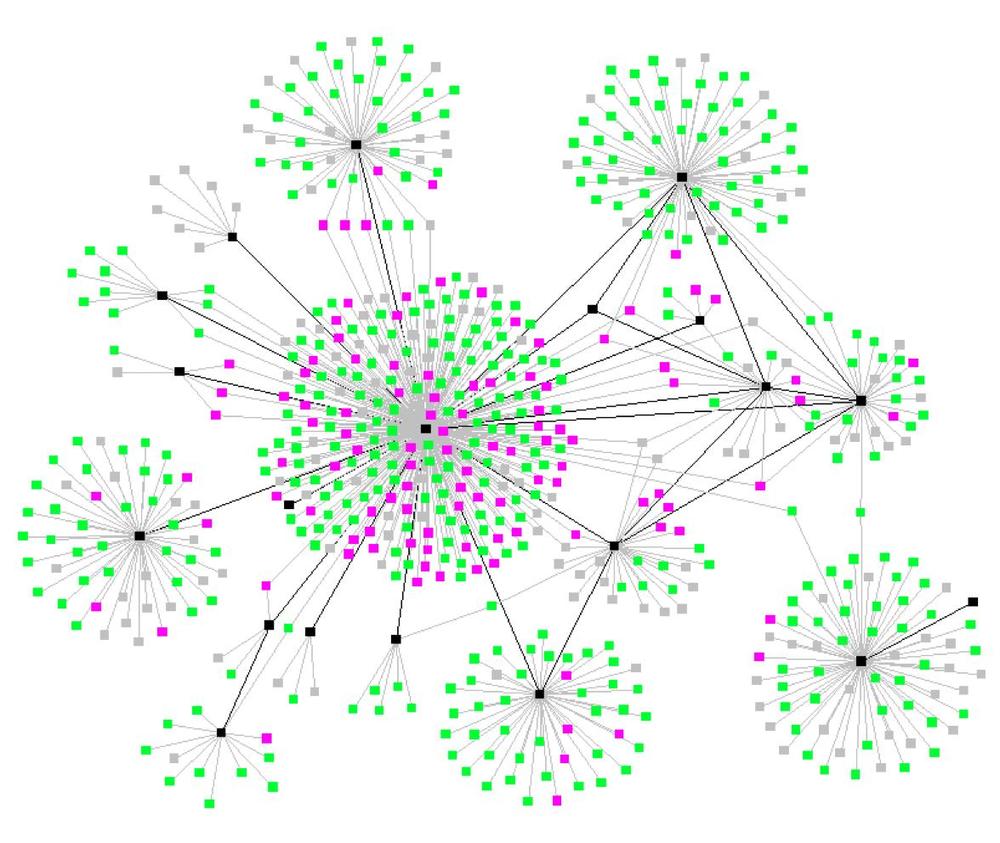

In nature, when an initial carrier is infected by a virus, that carrier then spreads the disease to the immediate environment, and from there, the infection spreads as carriers transition across borders to previously uninfected territories. Figure 12-6 shows an example of viral spread across population groups.

Distribution costs for viral marketing are lower because the audience becomes the medium. Making campaigns viral isn’t easy, however. You have to craft the right message and convince the audience to amplify it across many sites and platforms.

The classic example of online viral marketing is Hotmail. In its first 18 months of operation, Hotmail grew to 12 million users. At one point in 1998, the company was signing up 150,000 users a day. By comparison, a traditional print publication hopes to grow to 100,000 subscribers over several years. And Hotmail did it all with the seven short words shown in Figure 12-7.

During those 18 months, Hotmail spent less than $500,000. There were other factors that influenced its success, of course: most people didn’t already have web-based email; many people were connecting to the Internet for the first time; and the service was free. But an inherently social tool like email proved the perfect growth medium for the virus.

Note

There is some debate between the Hotmail founders and the main investors, Draper Fisher Jurvetson, as to whose idea it was to implement the email footer. In any case, the story had a happy ending: Microsoft acquired Hotmail in 1997 for $400 million, touting more than 9 million members worldwide at the time.

Viral marketing isn’t new. Decades before Hotmail’s record-breaking growth, Frank Bass published research on message diffusion and introduced marketers to the Bass Diffusion Curve.

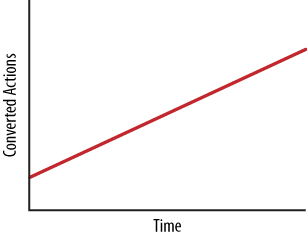

Traditional advertising campaigns are a function of two things: how many people hear your message, and how effective that message is in getting them to act. In other words, to get better results, you can either advertise to more people or you can improve the offer. This implies complete control over message power (the offer) and people who hear it (the reach).

Converted buyers = message power × people who hear it

Assuming a regular monthly expenditure on advertising (reaching the same number of people each month), the result of this traditional marketing model looks like the straight-line message diffusion curve shown in Figure 12-8. A convincing message reaching a certain number of listeners each month will result in a specific slope to the diffusion line—and the better the marketing message, the steeper the slope.

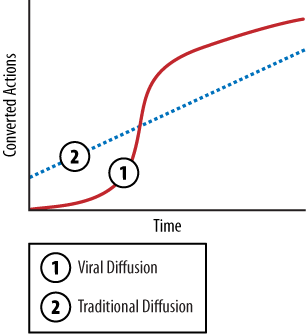

But Bass realized that there’s a second channel for your message—the buyers themselves. If your message is sufficiently engaging, your audience becomes your marketing medium. This second channel isn’t in your control, but it’s free. It’s word of mouth.

The Bass model adds a second element to the equation:

Converted buyers = message power × people who hear it +

(buyers × WOM power × People who hear it)In other words, in addition to traditional advertising reach, there’s word-of-mouth reach. And word of mouth grows as more people become amplifiers who adopt and repeat the message. The more amplifiers you have, the further your message travels until, ultimately, everyone has heard it.

The effect of word-of-mouth diffusion is strikingly different from traditional marketing, and yields the diffusion curve shown in Figure 12-9.

Early on, word-of-mouth diffusion isn’t very effective. Word of mouth starts off slowly, but as the number of buyers, users, or visitors builds, it can quickly outpace traditional marketing.

This doesn’t happen by itself. Viral marketing requires certain things to work well:

- A good story

Some marketing messages are inherently viral. Apple’s Steve Jobs calls inherently viral products “insanely great”—something so wonderful that you feel smarter when you tell others about it.

- Something of real value

While virality pays for its own distribution, you’ll need to work harder to craft your message. The Web is full of chain letters and goofy videos, but they’re not viral marketing unless they somehow lead to an outcome—they’re just entertainment.

Consider Gmail, Google’s web-based email offering. Unlike Hotmail, Gmail launched into a market that already had entrenched web mail platforms, such as Yahoo! and Hotmail. Google tried to differentiate itself by offering a hundred times the storage capacity of competing services, and by using an invitation-only model to drive adoption. By limiting invitations, the company was able to create perceived scarcity, which in turn drove up the perceived value of the service.

- Support from community leaders

You can improve viral marketing effectiveness by targeting supernodes—extremely connected inviduals—in social networks that have a broader reach and whose amplification has a greater impact because it spans several different groups.

- A large end audience

Viral marketing reaches a saturation point as the target audience hears and tires of the message (which is what gives it an S-shaped diffusion curve), so bigger markets are worth targeting. If your market is small or you can reach it efficiently through traditional means, it may be better served with more traditional, personalized advertising.

- A platform for distribution

Hyperlinks, videos, and pictures work well because they’re easily shared. The easier you make it for someone to tell another person about your message, the better you’ll do. Hotmail worked well because the product was itself a platform for spreading the message.

Note

Seth Godin’s Unleashing the Ideavirus (Hyperion) and Purple Cow (Portfolio Hardcover) deal with the issue of how to transmit ideas that others will pick up.

For an excellent overview of crafting messages that are easy to remember and pass on, see Chip and Dan Heath’s “Made to Stick” website at www.madetostick.com/.

Malcolm Gladwell’s The Tipping Point (Back Bay Books) is required reading on supernodes and how messages grow rapidly.

It’s important to set the right expectations for viral marketing within your organization, since it has fewer concrete, short-term effects.

In the early stages, when you’re seeding your message into the community, conversions from word of mouth will be low. Once a message gets into the hands of social hubs (networks of people with many casual friends and followers), the likeliness of message transmission greatly increases. If each user you bring in adds more than one user, you have a positive viral coefficient, and growth will follow.

Robert Zubek explains: “The viral coefficient is a measure of how many new users are brought in by each existing user. It’s a quick and easy way to measure growth: if the coefficient is 1.0, the site grows linearly, and if it’s less than that, it will slow down. And if the coefficent is higher than 1.0, you have superlinear growth of a runaway hit” (http://robert.zubek.net/blog/2008/01/30/viral-coefficient-calculation).

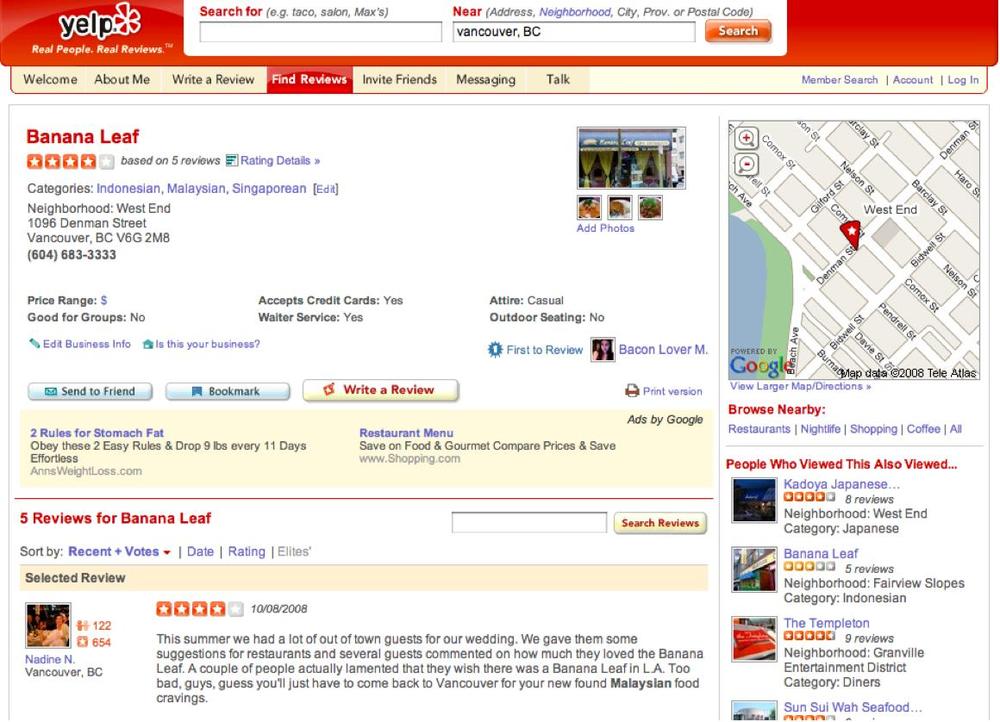

You can help prove the value of viral transmission to your organization by tracking word-of-mouth conversions separately from broadcast marketing. Get viral marketing right, and you’ll have a huge, cheap channel for your message. Hotmail adoption from June 1996 to June 1997, shown in Figure 12-10, closely follows the curve predicted by Bass’ research 30 years earlier.

In Hotmail’s case, the message was embedded in emails its users sent, and Hotmail controlled most of what was said as a result. You won’t be so lucky—as your message spreads, it will be diluted and misinterpreted. The Web will edit and repurpose it. Reactions and comments to the message might become more important than the message itself. Sometimes, entire communities will emerge around an idea as it becomes a part of online culture. Writer and evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins calls these cultural ideas memes. They’re transmitted from mind to mind, evolving and competing with other memes for prominence.

In the same way, communities relabel and repurpose viral marketing messages as they enter the Web’s zeitgeist, often at the expense of the original intent.

Consider, for example, a failed martial arts backflip that became the “Afro-ninja” Internet meme (www.youtube.com/watch?v=b_NQCTbvRnM), garnering millions of viewers. That this video was in fact related to an ad for the video game Tekken 5 was completely lost, and the marketing opportunity was missed entirely, despite its rapid spread to all corners of the Internet. Communities tend to do that. So why would we want to hand over our message to a Web that might change it?

Because we’re all skeptics.

We live in an attention economy where being noticed is the best currency. In his book Free, Wired Editor-in-Chief Chris Anderson cites social scientist Herbert Simon, who in 1971 predicted the rise of this attention economy, saying, “a wealth of information creates a poverty of attention.” Paris Hilton and Google both make money from their ability to steer our attention toward a particular product or service. And nothing gets our attention like the advice of a trusted source.

Community marketing and viral marketing are closely related, since both rely on the audience to amplify the message. But while viral marketing focuses on message spread, community marketing combines message redistribution with the genuineness of a message crafted by others.

Note

There are subtle differences in the types of community marketing messages that exist today. David Wilcox at the Social Reporter has a great blog post about this at http://www.designingforcivilsociety.org/2008/03/we-cant-do-that.html.

In community marketing, you engage the community through interaction, hoping that you’re able to make yourself the subject of discussions. It’s more about engaging and creating platforms for interaction like the one in Figure 12-11 than about crafting clever videos. It’s also often about listening and joining, rather than crafting the message yourself.

Community engagement helps to promote products or services, particularly for business-to-consumer marketing efforts. It also helps increase brand awareness. But communities are extremely wise—if the community marketing effort isn’t tied to genuine value, the community will rebel and the message will backfire, as it did for Belkin. Revelations that an employee had paid for positive product reviews online prompted anonymous letters claiming that the company engaged in even more deceptive practices. These far more damaging claims would likely never have surfaced if the disingenuous behavior of the initial employee hadn’t come to light. There’s a fine line between using a community to share your news and becoming the news itself.

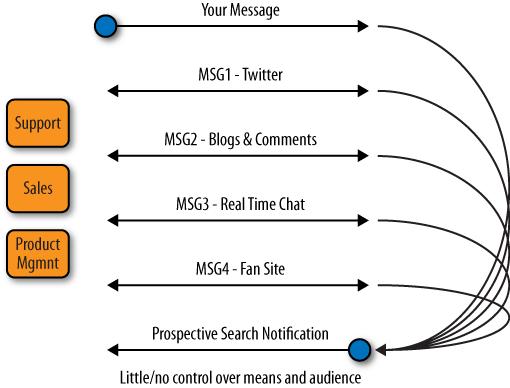

As online consumers become increasingly savvy, they can tell pitches from proponents with great precision. They flock to trusted peers. For example, sites like Chowhound, TripAdvisor, and Yelp (shown in Figure 12-12) have changed how consumers check out restaurants.

Figure 12-12. Yelp reviews are from real users, which makes them far more credible than those from marketers

Perhaps because of this, communities terrify traditional marketers. Community discussions peel back the veneer of a product, unearthing all manner of wart and weakness. Communities roam off in unexpected directions, as shown in Figure 12-13. Sometimes, they’ll talk about the message you’ve created; other times, they’ll talk about messages that one of your competitors has created about you. Most of the time, they simply won’t talk about you at all. When they do, however, you need to be ready to engage them.

Marketing communications in the age of widespread online communities consists of many different groups within an organization having many different dialogues. Gone are the hierarchies, the message approval, and the controlled release. In their place are many flows of information linking your organization to the rest of the Web, as shown in Figure 12-14. It’s very different from the controlled, predictable communications of broadcast marketing.

With little control over delivery or message, there are still five things you can do:

Create platforms where communities can flourish, such as groups, hashtags, and forums.

Find mentions of your message and your brand across the Web using search and referring URL tools.

Engage with communities so you can nurture and gently steer conversations.

Provide relevant content so you can grow customer loyalty and help the community to correct misinformation itself.

Build products and services that don’t suck.

Many people equate community management with next-generation marketing. It’s an obvious association: public relations has always been about getting the right message to as many people as possible, and because online communities are cheaper and more genuine vehicles for that message, they’re attractive. It would be wrong, however, to think that marketing is the only reason companies need to engage communities.