CHAPTER 2

Middle-Market Finance

A premise of this book is that private capital markets are unique. As such, unique capital market theories are required to explain and predict behavior of players in those markets. The main theory described in this book is middle-market finance theory, which is an integrated body of knowledge that applies to valuation, capitalization, and transfer of middle-market private companies. Several macro-events over the past 20 years have set the stage for the study of middle-market finance theory. These are:

- Private business valuation has become a career path. Dr. Shannon Pratt started this movement by publishing his landmark book, Valuing a Business: The Analysis and Appraisal of Closely Held Companies (McGraw-Hill) in 1981. Dr. Pratt was the first to bring structured thought to private business valuation. Partially due to his continued work, private business valuation has become quite sophisticated. There are now more than 5,000 practicing appraisers in the United States.

- Since the early 1990s, the private capital markets have developed many new capital alternatives. Prior to 1990, commercial lenders were the primary source of capital to private companies. In fact, if the local banker could not supply all of the capital needs of the owner-manager, the company probably went without necessary funding. Since that time, asset-based lenders, mezzanine players, private equity groups, and others have appeared. The variety of capital purveyors has enabled owner-managers to think in terms of capital structure and the various components of debt and equity that comprise it.

- Techniques to transfer private business interests have proliferated and become institutionalized. Transfer methods such as employee stock ownership plans, family limited partnerships, private auctions, and various other strategies are now available to owner-managers. Whether this transfer happens within the business to employees or a family member, or to an outsider, the owner-manager needs to become more knowledgeable. Owners often view transferring a business interest like grabbing the brass ring on a merry-go-round, but they need help improving their chances.

Most owner-managers and their professional advisors do not focus on the breadth of valuation, capital structure, and transfer issues, because they do not spend time dealing with this full body of knowledge. This book provides a resource for these individuals so they can structure and solve difficult financial problems in the private capital markets.

MIDDLE-MARKET FINANCE THEORY

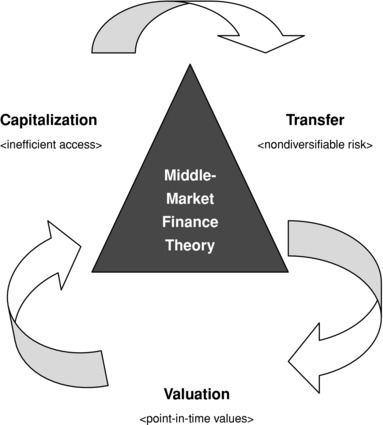

Middle-market finance theory is the integrated capital market theory unique to middle-market companies, especially those with annual sales of $5 million to $350 million. This theory describes the valuation, capitalization, and transfer of middle-market private business interests. These three interrelated areas rely on each other in a triangular fashion, as shown in Exhibit 2.1.

EXHIBIT 2.1 Structure of Middle-Market Finance Theory

Valuation forms the base of the triangle and is the foundation of middle-market finance theory. Valuation involves a rigorously defined process that ultimately derives what the company or business interest is worth. Valuation relies on input from the transfer leg of the triangle. The obvious transfer connections are selling multiples and other transactions that help derive values for similar situations. Without this feedback, much of valuation would be done in total isolation from the market and would quickly lead to nonsense. Since private securities do not have access to an active trading market, they rely on point-in-time appraisal or transactional pricing to determine value.

Capitalization, or capital structure formation, relies on valuation, the base of the triangle. The private capital markets allocate capital according to levels of risk and return. Private companies rely on proper valuations of assets, earnings, and cash flow to raise money. Unlike the public markets, private capital markets are characterized by inefficient access to capital. Private companies often cannot determine with any confidence whether they can access the funding they need.

Finally, transfer relies on capitalization. The business ownership transfer spectrum includes a broad range of alternatives. It spans the transfer of business interests to parties within the company to external parties. Transfer can occur only if capital is available to support the transaction. Transfer happens at a particular value that is determined using one of the defined valuation processes. Private investors cannot easily diversify their holdings due to the lack of liquidity in the private transfer market. This liquidity limitation increases the riskiness of the private transfer market, making things more difficult for private companies.

As Exhibit 2.2 shows, public and private markets use different names to describe key like-kind terms.

EXHIBIT 2.2 Public and Middle Market Names

| Public | Private Middle Market |

| Public capital markets (Wall Street) | Private capital markets (Main Street) |

| Corporate finance | Middle-market finance |

| Corporate finance theory | Middle-market finance theory |

TRIADIC LOGIC

A compelling logic holds the three conceptual sides of the triangle together. Unlike most financial logic based on positives and negatives, a triadic logic operating here provides powerful cohesion between the moving parts. A system of logic with three bases is dynamic rather than static and serves to bring the three sides of the triangle into a coherent whole. This is the logic of a three-legged stool. The reason for introducing this triadic logical structure is to demonstrate that it is not possible to remove one of the tenets in a dynamic system without destroying the system. Legs can be added, but the logical system is necessary and sufficient on its own to provide coherence to middle-market finance theory.

For example, consider removing the capitalization side of the triangle and attempting to transfer the business. It is practically impossible. Or try transferring a business without a process of valuation. Again, it makes very little logical sense. Finally, an attempt to value a business without considering a possible transfer or how that transfer is capitalized is untenable.

MIDDLE-MARKET FINANCE THEORY IN PRACTICE

Middle-market finance theory is the integrated body of capital market theory that describes the valuation, capitalization, and transfer of middle market private business interests. Each of the three sides of the conceptual triangle exhibits a unique framework.

Value World Theory

Private securities do not enjoy access to an active trading market. Either a private valuation must be undertaken, or a transaction must occur to determine the value of a private security for some purpose at some point in time. “Purpose” is defined as the intention of the involved party or the reason for the valuation. Purpose leads to the function of an appraisal. “Function” is described as the intended specific use of an appraisal. Specific functions of a valuation require the use of specific methods or processes, each of which can derive dramatically different value conclusions. The purposes (sometimes called “reasons”) for undertaking an appraisal are referred to herein as giving rise to value worlds. Therefore, here is the premise of value world theory:

A private business value is relative to the value world in which it is viewed.

Every private company, therefore, has a number of different values at the same time, depending on the purpose and function of the valuation. The purpose of the appraisal governs the selection of a value world. Each value world follows a defined process to determine value under specific rules, based on the function of the appraisal. Each value world may have multiple functions. Each world also has an authority, which is the agent or agents that govern the world. The authority decides whether the intentions of the involved party are acceptable for use in that world as well as prescribes the methods used in that world.

Exhibit 2.3 lists a number of value worlds, with associated purposes, functions, and authorities.

EXHIBIT 2.3 Value Worlds Concept Chart

Examples of authority are found in each appraisal world. For instance, the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) is the authority in the world of impaired goodwill. FASB is responsible for developing criteria and administering methodology used to derive value and for sanctioning noncompliance.

By understanding the logic, definitions of process, and treatment of facts within each world, it becomes clear that private valuation is possible only within a set of parameters: a value world.

The intention or motive of the involved party leads to a purpose of an appraisal. This is the starting point in the valuation discussion. Purposes for undertaking an appraisal give rise to value worlds. The logical construct of a value world is independent of the experience of individual appraisers and individual assignments. Value then is expressed only in terms consistent with that world. Once the project is located in a value world, the function of the appraisal governs the choice of appraisal methods. The responsible authority in each value world prescribes these methods. The choice of appropriate appraisal methods ultimately may lead to a point in time singular value. Thus, a private business value is relative to the purpose and function of its appraisal.

Private Capital

Capitalization, or capital structure formation, is the second leg of the private capital market triangle. “Capital structure” refers to the composition of the invested capital of the business, typically a mixture of debt and equity financing. For private companies, these securities range from placing industrial revenue bonds, to receiving mezzanine capital, to issuing common equity to venture capital firms. Private capital markets are much less efficient than their public counterparts. In fact, due to the lack of an organized market, private capital market solutions are created one at a time. In other words, private capital is assembled on a deal-by-deal basis.

Yet there is a structure of capital alternatives in the private markets. Unlike the organized structure that defines the public capital markets, private markets are more ad hoc, which leads to the next statement:

Private markets can be thought of as outdoor bazaars rather than public supermarkets of securities.

Nearly all capital alternatives are available in the private bazaar, but they are found in separate shops or discrete increments. Financing is more difficult in the private markets because capital providers in the bazaar constantly move around and may or may not rely on prior transactions to make current decisions. Fortunately for those in need of private capital, some organization in this bizarre bazaar can be discerned.

For assistance in empirically describing the private capital markets, the author partnered with Pepperdine University to conduct a series of surveys. These Pepperdine Private Capital Markets Surveys began in April 2009 and have continued every six months to the time of this writing.1 These surveys help overcome a major shortfall in the first edition of this book, which was based mainly on anecdotal evidence.

The Pepperdine survey project is the first comprehensive and simultaneous investigation of the behavior of the major private capital types. The surveys specifically examine the behavior of senior lenders, asset-based lenders, mezzanine funds, private equity groups, venture capital, angel investing, and factoring firms. The Pepperdine surveys investigate, for each private capital type, the important benchmarks that must be met in order to qualify for capital (called “credit boxes”), how much capital typically is accessible, and what the required returns are for extending capital in the current economic environment. This book incorporates empirical data from the surveys into the discussion wherever possible.

Capital types are segmented into various capital access points (CAPs). The CAPs represent specific alternatives that correspond to institutional capital offerings in the marketplace. For example, asset-based lending is a capital type, and Tier 1 and Tier 3 are examples of capital access points within that type. Exhibit 2.4 shows the capital types with corresponding capital access points that were surveyed, along with one capital type—equipment leasing—and a number of capital asset points mentioned in this book that have not been surveyed. Examples of nonsurveyed CAPs are government lending programs, such as Small Business Association 7(a) or 504 loan programs. These nonsurveyed CAPs are derived mainly from programs that are readily observed in the marketplace.

EXHIBIT 2.4 Structure of Capitalization

| Capital Types | Capital Access Points |

| Bank lending | Industrial revenue bonds |

| SBA 504 loans | |

| Business and industry loans | |

| SBA 7(a) loan guaranty | |

| SBA CAPLine credit lines | |

| Credit lines | |

| Export working capital loans | |

| Equipment leasing | Bank leasing |

| Captive/vendor leasing | |

| Specialty leasing | |

| Venture leasing | |

| Asset-based lending | Tier 1 asset-based loans (ABLs) |

| Tier 2 ABLs | |

| Tier 3 ABLs | |

| Factoring | Low volume |

| Medium volume | |

| High volume | |

| Mezzanine | Mezzanine |

| Private equity | Angel financing |

| Venture capital | |

| Private equity groups |

Accessing private capital entails several steps. First, the credit box of the particular CAP is described. Credit boxes depict the criteria necessary to access the specific capital. Next, each CAP defines sample terms. These are example terms, such as loan/investment amount, loan maturity, interest rate, and other expenses required to close the loan or investment. Finally, by using the sample terms, an expected rate of return can be calculated. This rate is the expected or “all-in” rate of return required by an investor. It is not sufficient to consider the stated interest rate on a loan. Other factors, such as origination costs, compensating balances, and monitoring fees, add to the cost of the loan.

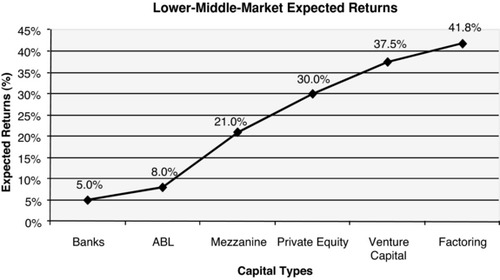

EXHIBIT 2.5 Pepperdine Private Capital Market Line

Once all of the capital types are described and their expected returns determined, it is possible to graph the Pepperdine Private Capital Market Line (PPCML), shown in Exhibit 2.5. The PPCML is empirically defined, since the capital asset pricing model or other predictive models are not suitable for use in creating the expected rates of return in the private markets. Somewhere on or near this line is the expected return of the major institutional capital alternatives that exist in the private capital markets.

Exhibit 2.5 encompasses various capital types in terms of the provider's all-in expected returns. The PPCML is described as median, pretax expected returns of institutional capital providers. For consistency, the capital types chosen to comprise the PPCML reflect likely capital options for mainly lower-middle market companies. For example, the PPCML uses the “$5 million loan/investment” survey category for banks, asset-based lending, mezzanine, and private equity. It should be noted that the PPCML could be created using different data sets.2 The returns are further described as first and third quartiles, as shown in Exhibit 2.6.

EXHIBIT 2.6 Pepperdine Survey Capital Types by Quartiles

The PPCML is stated on a pretax basis, both from a provider and from a user perspective. In other words, capital providers offer deals to the marketplace on a pretax basis. For example, if a private equity investor requires a 25% return, this is stated as a pretax return. Also, the PPCML does not assume a tax rate to the investee, even though many of the capital types use interest rates that generate deductible interest expense for the borrower. Capital types are not tax-effected because many owners of private companies manage their company's tax bill through various aggressive techniques. It is virtually impossible to estimate a generalized appropriate tax rate for this market.

The PPCML is helpful to companies that are forming or adding to their capital structure. The financing goal of every company is to minimize its effective borrowing or investment costs. Companies should walk the private capital line to achieve this goal. This means borrowers should start at the least expensive lowest part of the line and move up the line only when forced by the market.

Business Transfer

The final part of the book describes the transfer of private business interests. There are a variety of options available to transfer a private business interest. Business interests are any part of a company's equity or ownership interest. “Business transfer” covers the spectrum of transfer possibilities from transferring assets of a company, to transferring partial or enterprise stock interests.

Transfer channels represent the highest level of choice for private owners. Owner motives are the basis for selecting transfer channels. Transfer methods— the actual techniques used to transfer a business interest—are grouped under transfer channels.

EXHIBIT 2.7 Business Ownership Transfer Spectrum

An owner has seven transfer channels from which to choose. The channels are:

1. Employees

2. Charitable trusts

3. Family

4. Co-owners

5. Outside—retire

6. Outside—continue

7. Public

The choice of channel is manifested by the owner's motives and goals. For instance, owners wishing to transfer the business to children choose the family transfer channel. Owners who desire to transfer the business to an outsider then retire choose the outside—retire channel; and so on. Exhibit 2.7 is a schematic representation of transfer channels and transfer methods in the business ownership transfer spectrum.

Each transfer channel contains numerous transfer methods. A transfer method is the actual technique used to transfer a business interest. For example, grantor-retained annuity trusts, family limited partnerships, and recapitalizations are methods by which an interest is transferred. Certain methods are exclusively aligned with certain channels, such as an employee stock ownership plan (ESOP) within the employee transfer channel. Other methods can be applied across channels, such as the use of private annuities with either the family or outside channels.

Transfer methods correspond to specific value worlds. For instance, transferring stock into a charitable trust occurs in the world of fair market value. Selling stock via an auction happens in the world of market value; and so on. The connection between transfer methods and value worlds produces a major tenet of private business transfer:

The choice of transfer method yields a business interest's likely value.

An owner's motive for a transfer leads to the choice of a transfer method, which is linked to a value world. Each value world employs a unique appraisal process that yields a particular value. In other words, an owner can plan the timing and value of business in a transfer.

When a business interest transfers within the company itself, it is called an internal transfer. Internal transfers comprise the transfer methods that are custom-tailored solutions for use by owners who wish to transfer part or all of the business internally and avoid the uncertainty of finding an outside buyer for the business. Examples of internal transfers methods are management buyouts, charitable remainder trusts, family limited partnerships, and a variety of estate planning techniques.

Business interests that transfer to a party outside the company are called external transfers. Once again, the term “external transfer” provides a way to discuss transfer methods useful to an investor or buyer outside of the business. As the name implies, external transfers employ a process to achieve a successful conclusion. Examples of external transfers include negotiated sales, roll-ups, and reverse mergers. As an illustration, if an owner of a medium-size company wants to sell a business for the highest possible market price, he might employ a private auction process, which should produce the highest possible offers available in the market at that time.

The goal of the business transfer section is to alert private business owners and their professionals to the large number of transfer options that exist. Owner motives usually lead to the choice of a transfer channel. Each channel houses numerous transfer methods. The methods enable an owner to convert motives into actions. Due to the technical nature of business transfer, this section is written to give interested players a guide to the various alternatives. Once a road map is conceived, an owner should engage experts to tailor the solution to the need.

OWNER MOTIVES

A motive is a goal that initiates an action. The governing authority must sanction an owner's motive for a goal to be met.

Motives of private business owners initiate an action. Motives are not like dreams in that dreams do not lead to action. For example, many private business owners dream of going public, yet 99.9% never become public entities because authorities in the market must support the motive and provide it with additional momentum. No positive outcome is possible without this additional support. Authorities control both access and the rules of the game within their spheres of influence. In the case of going public, a private owner must convince a public investment banking firm, the authority, to take the company public.

Unintended consequences occur when private business owners act without considering the governing role of authorities. The owner who attempts to give stock to children, without acknowledging Revenue Ruling 59-60, may receive an unwelcome visit from the Internal Revenue Service (IRS). Or the owner attempting to raise venture capital money without regard to the venture capitalist's credit box may simply waste time and effort.

Private owners need to understand the mutually exclusive features and functions of the private capital markets. Once the motive initiates action, specific possibilities are opened and closed. This occurs because the owner's motives initiate action from each side of the triangular body of knowledge that forms connections between features and functions. By launching the initial motive without proper information, the owner unknowingly chooses a course of action that narrows future options. For instance, although owner's motives select the appropriate value world, once located in a value world, only a limited number of capital access points may be available. Within the value world and preselected capital access points, only a few transfer methods may be available. The available transfer methods, capital access points, and ultimate price an owner receives triangulate with the value world originally determined by the owner's motives.

For instance, an owner may be motivated to transfer the business to the employees via an ESOP. Since ESOPs are valued in the world of fair market value, the owner's motives cause the company to be valued in this hypothetical world without synergies. Most ESOPs are financed by bank lending. Further suppose the owner wants to transfer the company to the key managers. Managers live in the world of investment value and are constrained by their ability to finance the purchase price. The managers may access secured lending to finance the deal but may not be able to access private equity without losing control of the company. The owner may be able to increase the purchase price into the world of owner value if she is willing to finance the deal through seller notes. Finally, an owner who wishes to sell to a synergistic buyer in a consolidation makes the conscious decision to enter the synergy subworld of market value. An owner's motives drive the price she receives in a transfer.

AUTHORITY

Once an owner sets a goal, the relevant authorities must be heeded. Authorities set the rules and processes regarding business valuation, capital structure formation and business interest transfer. Authorities in the private capital markets provide these rules and act as traffic cops to ensure compliance. The concept of authority helps explain how and why things happen the way they do.

“Authority” refers to agents or agencies with primary responsibility to develop, adopt, promulgate, and administer standards of practice within the private capital markets. Authority derives its influence or legitimacy mainly from government action, compelling logic, and/or the utility of its standards. Exhibit 2.8 describes the sources of legitimacy for authority. Authority sanctions its decisions by veto power or denying access to the market.

EXHIBIT 2.8 Sources of Legitimacy for Authority

| Government Action | Compelling Logic | Utility |

| Many authorities derive their legitimacy through government action. Government action often regulates the valuation process, capital allocation, and the methods by which to transfer business interests. State and federal authorities typically have strong sanctioning power due to the threat of legal action. Government-based authorities ultimately are limited by the consent of the governed. | Authority grounds the language and logic in the community it serves. Membership entails using this language and, when it is deemed useful, following the logic. The membership provides market feedback to the authority when it believes the compelling logic is not useful or could be improved. An example of an authority that fights to win the logic battle are the ERISA laws and the various ESOP service providers. | Authority derives legitimacy from the utility of its logic and actions. Utility is measured by how well it helps members accomplish their objective. Examples of utility in valuation is the management consultant's espousal of incremental business value. Unless constituents accept the utility of the authority's argument, incremental business value will not be adopted. |

Each of the three areas of the private capital markets has dozens of authorities. For example, in valuation, the IRS and tax courts are the primary authorities in the world of fair market value. In capital, various capital providers such as banks and venture capitalists are authorities. Finally, in business transfer, authorities may be laws, such as the Employee Retirement Income Security Act laws for ESOPs, or investment bankers for reverse mergers.

Every authority has a boundary that forms the limit of its influence. The most obvious boundary is the utility of the logic or action that the authority promotes. In other words, if an authority promulgates rules that do not make sense to its constituency, the rules may be ignored or challenged. Even the mighty IRS is countered by the tax courts when members believe the former's rules are misdirected. This has been the case over the past 20 years regarding lack of marketability discounts. Tax courts have consistently ruled against the historic IRS position that private business interests suffer only slightly as compared to public interests.

Authorities have varying degrees of sanctioning power. The most direct sanction is veto power. Capital providers do not have to supply the requested money. Or the IRS can challenge an appraisal in court. Many authorities sanction noncompliance by denying access to information or a market. For instance, financial intermediaries who believe shareholders are overvaluing their company might choose not to represent it in a sale.

Each chapter discusses authority, especially as it relates to mandated processes and the legitimacy of the authority's position.

TRIANGULATION

The concept of triangulation demonstrates middle-market finance theory as a holistic body of knowledge. It requires an understanding of the entire framework before a specific technique or method can be properly considered and fully understood. That is why this work is consolidated into one book, covering valuation, capitalization, and business transfer as interrelated topics.

EXHIBIT 2.9 Triangulation

Points located on the various sides of the middle-market finance theory triangle do not exist in isolation. It is useful to borrow a loosely constructed concept of triangulation from navigation or civil engineering, where a point is located only with reference to other points. Once a point is identified and described, it can be used as a survey monument or control point to mark its location and relationship with other points. “Triangulation,” graphically depicted in Exhibit 2.9, refers to the use of two sides of the middle-market finance theory triangle to help fully understand a point on the third side. Control networks can then be created using triangulation with various orders of accuracy. In economics, as in surveying, triangulation can help map out unknown territory by establishing relationships with what is known.

While there is no claim for mathematical accuracy or certainty in applying the concept of triangulation to the private capital markets, its application may bring useful insights. What is known about two control points on legs of the triangle can be used to locate and understand a third point. The process helps to think about relationships, understand interconnections, and eliminate errors.

On a macro level, triangulation can be summarized in three interrelated sentences:

1. Business value is directly affected by the company's access to capital and the transfer methods selected by or available to the owner.

2. Capitalization is dependent on the value world in which the company is viewed and the availability of transfer methods.

3. The ability to transfer a business interest is conditioned by its access to capital and the value world in which the transfer takes place.

Triangulation is a further embodiment of triadic logic, which describes middle-market finance theory using a three-legged conceptual stool. In other words, private valuation can be understood only relative to capital/transfer, capitalization must be viewed relative to the impact of valuation/transfer, and transfer is influenced by capitalization/valuation.

Perhaps an example of triangulation will help. Assume Joe Mainstreet, controlling shareholder of PrivateCo, the fictitious company described in this book, wants to diversify his estate and sell the business. Doing so typically calls for an appraisal in the world of market value. Joe has numerous transfer methods from which to choose that will meet his goal. For instance, he may sell to his management team (management buyout), to an outside strategic acquirer (private auction), or to a private equity group (recapitalization), and so on. The choice of transfer method dramatically affects the value of PrivateCo. It is likely that PrivateCo is worth far less to his management team than to a synergistic acquirer because the former does not bring synergies to the deal. Further, management is limited by its ability to raise capital for the purchase; whereas the acquirer may not have this problem. Joe may help improve the management's value by financing part of the transaction. While seller financing helps Joe get a higher value for PrivateCo, it also puts him in a riskier position going forward. This is the key to understanding triangulation. Joe Mainstreet cannot view the value of PrivateCo properly without considering the effect that transfer and capital has on the situation. This same triangulated framework of decision making is required no matter which part of the private capital market triangle triggers the action.

Since owner motives jump-start the triangulation process in middle-market finance theory, nearly every chapter of this book begins with motives of the owner and ends with triangulation. In this way the reader can establish the owner's decision-making process and ascertain the effect all sides of the middle-market finance theory triangle have on the decision.

NOTES

1. John K. Paglia, Pepperdine Private Capital Markets Project Survey Report, April, 2010, bschool.pepperdine.edu/privatecapital.

2. The Pepperdine surveys are delineated by quartiles and investment size, which allows for numerous capital market lines. The Pepperdine Private Capital Market Line (PPCML) shown is this book is representative of the capital alternatives available to lower-middle-market companies. Unless otherwise stated, the PPCML will use data from the “$5 million loan/investment” category of the April 2010 Pepperdine survey.