CHAPTER 25

Capital Structure: Conclusion

Since the ability to access capital directly affects the value of a business, owner-managers need to understand the ramifications of this value-capitalization relationship in the private capital markets. The previous chapters described the fundamental concepts underlying the capitalization of private businesses. This chapter builds on these fundamentals with a discussion of these issues:

- Capital providers use credit boxes and other devices to manage risk and return in their portfolios.

- Expected returns to institutional capital providers comprise the Pepperdine Private Capital Market Line.

- Private cost of capital emanates from the private capital markets.

- High cost of capital limits private company value creation.

- Intermediation is relatively ineffective in the middle market.

- Capitalization is triangulated to valuation and business transfer.

CAPITAL PROVIDERS MANAGE RISK AND RETURN IN THEIR PORTFOLIOS

Capital providers use credit boxes and other devices to manage risk and return in their portfolios. Institutional capital providers use portfolio theory to obtain this goal. Diversifying risk while optimizing return is the promise of portfolio theory. It is built on the premise that the risk inherent in any single asset, when held in a group of assets, is different from the inherent risk of that asset in isolation.

Capital providers employ credit boxes to filter asset quality and set return expectations. In other words, loans or investments that meet the terms of a provider's credit box should promise a risk-adjusted return that meets the needs of the provider. The provider then uses a number of devices to manage the risk and return of its portfolio. Exhibit 25.1 shows the relationship between the credit box and portfolio management.

EXHIBIT 25.1 Credit Portfolio Management

Capital providers use a number of tools to manage their portfolios. Simple techniques, such as advance rates and loan terms, enable the provider to hedge risk. Providers use other measures to manage risk, such as interest rate matching and hedges, and diversify investments across geography and industries. Loan covenants are the major risk/return management tool for providers. By setting boundaries around the behavior of a borrower or investee, a capital provider is better able to manage its portfolio. Borrowers who do not comply with covenants may have their loans accelerated. In other words, these borrowers are asked to find another source of capital. Providers monitor their portfolios and feedback information to their credit boxes to adjust the characteristics of new assets that enter the portfolio.

Lenders’ and investors’ portfolios constitute the limit of their expected returns, and managing this limit creates market fluctuations. Similarly, owners manage a balance sheet with a blend of equity and debt. In other words, owners manage a portfolio of equity and debt to maximize use of capital and manage exposure to risk. It is the day-to-day operation of these portfolios of investments through various market mechanisms that defines the market at any moment in time.

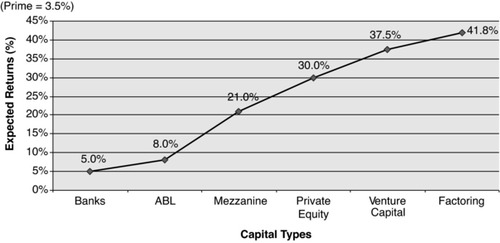

THE PEPPERDINE PRIVATE CAPITAL MARKET LINE COMPRISES EXPECTED RETURNS

The first edition of Private Capital Markets relied on anecdotal evidence to support the private capital access line, which graphed various expected returns of institutional capital providers. Describing the market via anecdotal evidence was insufficient, so the author partnered with Pepperdine University to conduct a series of surveys. These Pepperdine Private Capital Markets Surveys began in April 2009 and have continued every six months to the time of this writing. These surveys help overcome a major shortfall in the first edition of this book, which was based mainly on anecdotal evidence.

The Pepperdine survey project is the first comprehensive and simultaneous investigation of the behavior of the major private capital types. The surveys specifically examine the behavior of senior lenders, asset-based lenders, mezzanine funds, private equity groups, venture capital, angel investing, and factoring firms. The Pepperdine survey investigates, for each private capital type, the important benchmarks that must be met in order to qualify for capital, how much capital typically is accessible, and what the required returns are for extending capital in the current economic environment. This book incorporates empirical data from the surveys into the discussion wherever possible.

Capital types are segmented into various capital access points (CAPs). The CAPs represent specific alternatives that correspond to institutional capital offerings in the marketplace. For example, asset-based lending is a capital type, and Tier 1 or Tier 3 is an example of CAPs within that type. Exhibit 25.2 shows the capital types with corresponding CAPs that were surveyed, along with one capital type—equipment leasing—and a number of CAPs mentioned in this book that have not been surveyed. Examples of non-surveyed CAPs are government lending programs, such as Small Business Administration 7(a) or 504 loan programs. The author believes these nonsurveyed CAPs are derived mainly from programs that are readily observed in the marketplace.

EXHIBIT 25.2 Private Return Expectations Viewed through the PPCML

Accessing private capital entails several steps. First, the credit box of the particular CAP is described. Credit boxes depict the criteria necessary to access the specific capital. Next, each CAP defines sample terms. These are example terms, such as loan/investment amount, loan maturity, interest rate, and other expenses required to close the loan or investment. Finally, by using the sample terms, an expected rate of return can be calculated. This rate is the expected, or “all-in,” rate of return required by an investor. It is not adequate to consider the stated interest rate on a loan. Other factors, such as origination costs, compensating balances, and monitoring fees, add to the cost of the loan. Once all of the capital types are described and their expected returns determined, it is possible to graph the Pepperdine Private Capital Market Line (PPCML), shown in Exhibit 25.2.

The PPCML is stated on a pretax basis, both from a provider and from a user perspective. In other words, capital providers offer deals to the marketplace on a pretax basis. For example, if a private equity investor requires a 25% return, this is stated as a pretax return. Also, the PPCML does not assume a tax rate to the investee, even though many of the capital types use interest rates that generate deductible interest expense for the borrower. Capital types are not tax-effected because many owners of private companies manage their company's tax bill through various aggressive techniques. It is virtually impossible to estimate a generalized appropriate tax rate for this market.

The returns shown on the PPCML are median returns of the capital types. There can be substantial variances from the median based on segmentation within the capital type, called CAPs. For example, asset-based lending (ABL) is segmented into three CAPs. Tier 1 ABLs typically make funding commitments of at least $10 million per borrower; Tier 2 ABLs fund from $3 million to $10 million; and Tier 3 ABLs usually provide funding of less than $3 million. CAPs price for risk accordingly, such that Tier 1's may have a median return expectation of less than 10%; Tier 2's may be close to 13%; and Tier 3's may require above 15% to provide funds to a riskier clientele. Pepperdine surveys the private markets every six months and hopes to report by CAP in the future.

PRIVATE COST OF CAPITAL EMANATES FROM THE PRIVATE CAPITAL MARKETS

The temptation to use readily available public information to value private companies is strong. Note that within private capital markets, only academics and business appraisers use the guideline public company method. Other parties in private capital markets—business owners, lenders, investors, estate planners, and so on—rely on valuation methods that are specifically useful to making decisions in their markets.

Why do not parties in private capital markets employ public information in their decision-making process? Because these parties have real money in the markets; valuation is not notional to them. Making proper financing and investment decisions requires using theories and methods that are appropriate to the subject's market.

To help managers and others make better investment and financing decisions, the author created the Private Cost of Capital (PCOC) model, shown next.

![]()

where: N = number of sources of capital

CAPi = median expected return for capital type i

SCAPi = specific CAP risk adjustment for capital type i

MVi = market value of all outstanding securities i

This discount rate is empirically derived and threatens to alter professional, legalistic, compliance business appraisal in five ways. First, adjustments such as lack of marketability discounts and control premiums are not needed. These adjustments were created originally based on the faulty premise that public return expectations could be manipulated to derive private values. Once risk is defined using private return expectations, these public-to-private adjustments are unnecessary.

Second, PCOC provides a risk definition that can be applied across value worlds (standards of value). Each world also has an authority, which is the agent or agents that govern the world. The authority decides whether the intentions of the involved party are acceptable for use in that world and prescribes the methods used in that world. More specifically, “authority” refers to agents or agencies with primary responsibility to develop, adopt, promulgate, and administer standards of practice within that world. Authority decides which purposes are acceptable in its world, sanctions its decisions, develops methodology, and provides a coherent set of rules for participants to follow. Authority derives its influence or legitimacy mainly from government action, compelling logic, and/or the utility of its standards. Authorities from the various value worlds will have an empirically derived method of defining risk. It is hoped that these authorities will prescribe use of PCOC in their respective worlds.

Third, business owners will have the ability to determine their company's cost of capital. This knowledge will help them learn whether they are creating incremental business value (i.e., generating returns on invested capital greater than this cost). This should promote incremental business value creation as a practical and useful tool. Plus it opens an avenue for business valuators to consult with business owners to help them make better investment and financing decisions.

Fourth, the PCOC model will make business appraisal more relevant. Currently, an industry of business appraisers inhabits mainly the notional value worlds. Business owners need more help in competing in a global economy. Tools like the PCOC model will help the appraisal industry become more value-added.

Finally, by employing empirical data from the private capital markets to derive a private discount rate, we can better understand whether management actions are creating company value. The PCOC model enables users to view value in the incremental business value world, which, for the first time, will enable them to make decisions that generate returns on investment greater than their company's cost of capital.

HIGH COST OF CAPITAL LIMITS PRIVATE COMPANY VALUE CREATION

The author believes that most private business owners are not increasing the value of their firms.1 This is an incredibly strong statement, since it means that the largest part of the American economy is slowly but surely underperforming to the point of going out of business.

Specifically, most business owners are not generating returns on investment greater than their company's cost of capital. Of course, substantial study needs to be done in this important area. But it should not come as a complete surprise that so little value is being created in the private capital markets. Until the recent Pepperdine surveys, no one knew how expensive private cost of capital really is. Also, most business owners do not know why it is important to know their company's cost of capital. These owners use payback or gut feel to make investment decisions, which are the equivalents of Stone Age tools used to build a skyscraper. Certainly we can do better in the twenty-first century.

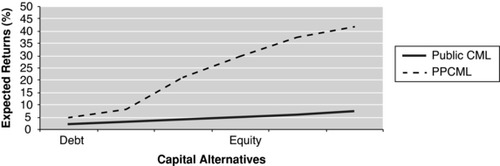

For this discussion, it is important to distinguish between public and private cost of capital. As Exhibit 25.3 depicts, private cost of capital is more than twice as costly, on average, as large public companies’ capital. In other words, to create incremental business value, private companies must generate returns on investment of more than twice as high as their public counterparts. With no investment decision-making framework to guide them, most business owners are not making maximizing value creation decisions.

EXHIBIT 25.3 Public Capital Line versus Pepperdine Private Capital Market Line

Private company managers need to be educated and trained on cost of capital in a way that positively influences their decision making. This is especially important with global competition. Until this training occurs, it is likely that the private capital markets will continue to underperform financially.

INTERMEDIATION IS RELATIVELY INEFFECTIVE IN THE MIDDLE MARKET

Most capital that flows into the middle market is intermediated. This means that professionals, mainly private equity groups, venture capitalists, and mezzanine providers, raise monies from institutions and then invest in middle-market companies, with the hopes of earning a return that is commensurate with the risk of the investment. This investment model has not been effective, as Exhibit 25.4 depicts.

EXHIBIT 25.4 Middle-Market Expected versus Realized Returns

Intermediaries structure their investments in hopes of making an expected return. The expected returns from the most recent Pepperdine survey for several private investor types are listed in the exhibit.2 It is important to note that these intermediaries issue term sheets and then fund opportunities with the goal of earning, on average, these expected returns (before costs). Venture capitalists earning a 38% return on their investments, for instance, would be considered successful.

The realized returns from Exhibit 25.1 are taken from a Thomson Reuters study. For decades Thomson Reuters has collected data on actual public and private investment returns. Notice that none of the capital providers is meeting its investment goals over a 5- to 20-year investment horizon.3 In fact, even if we add back the 5% to 7% for management fees, the realized return is dramatically lower than the expected returns for each provider. What are we to make of this shortfall?

Little research has been done in this area, but the author suggests several possible explanations. First, intermediaries themselves have typically not been educated or trained in private company value creation. More often than not, they have been educated at America's top MBA schools, which have historically not focused their curricula on growing private companies. Most MBA schools spend most of their time preparing students for life in a large public multinational corporation and not for the grind of growing a middle-market company.

Second, the intermediaries that cannot create value must rely on the skills of the owner-manager to do the work. But the vast majority of owner-managers have also not received any education or training on private company value creation and probably do not have a value creation framework on which to rely.

Finally, private cost of capital is so high that only handfuls of companies routinely generate returns on investment sufficient to create value. Therefore, intermediaries use a portfolio approach to value creation, where just a few winners are meant to overcome all of the losing investments. Over the past 20 years, this investment model has not worked, meaning that it has not created value for investors.

The foregoing suggests that the intermediaries that have realized substandard returns will not be able to raise new funds going forward and that a new investment model ultimately will replace the current intermediation construct.

TRIANGULATION

Triadic logic is a compelling logic holding the three conceptual sides of the private capital markets triangle together. It provides a powerful cohesion between the moving parts. An idea that originates on the capitalization leg of the triangle finds its opposite or counterpart in the valuation leg and transfer leg. Another way of looking at triangulation is that each side of the triangle creates a feedback effect, or loop, to the other sides. It is impossible to view capitalization without considering the influence of valuation and transfer. In a practical sense, this balancing act links private capitalization, valuation, and transfer.

The choice of capital structure matters to a private company. It directly influences a company's ability to create shareholder value because the balance sheet sets the minimum threshold for a company's cost of capital. Investments in the business must meet this threshold, or value is destroyed.

Ultimately, owner-managers can increase value by minimizing unsystematic risks. These are the risks that are company specific and cannot be diversified away. Building a functional organization is a good start, but maintaining a “balanced” balance sheet also limits unsystematic risks. In either event, these activities are within the owner-manager's control. Activities as simple as obtaining audited financial statements, paying attention to industry-generated ratios on key balance sheet items, and implementing an economic valuation method all work to reduce unsystematic risks.

Expected investor returns are derived from the capital side of the private capital markets. Owner-managers who ignore their balance sheets for the siren song of the income statement are likely to run underperforming businesses. Many companies run out of cash and go bankrupt because of failure to recognize the importance of the balance sheet. Most companies do not encounter these problems because they exhibit a lack of concern for the income statement. Owners who would not consider overpaying a supplier or overpaying for any other resource in the company frequently do not concern themselves with the effective use of their capital. This oversight makes just about all other business mistakes look inexpensive.

NOTES

1. Rob Slee, “Using the Incremental Business Value Model,” Valuation Strategies (September 2010), pp. 20–25.

2. John K. Paglia, Pepperdine Private Capital Markets Project Survey Report, April 2010, John K. Paglia, bschool.pepperdine.edu/privatecapital.

3. Thomson Reuters Corporation, www.thomsoneuters.com, August 10, 2010.