CHAPTER 14

Other Value Worlds

There are a number of value worlds beyond those described in other chapters. Worlds emanate from the multitude of reasons for which a private appraisal might be needed. These reasons may require using specific methods or processes for the valuation, which causes a host of different value worlds. Some of the other worlds are briefly summarized in this chapter. These other worlds are no less important than previously mentioned worlds; they simply require less space to explain. This chapter describes six worlds and discusses the processes used to derive value in each:

1. Investment value world

2. Owner value world

3. Collateral value world

4. Early equity value world

5. Bankruptcy value world

6. Public value world

INVESTMENT VALUE WORLD

The world of investment value describes the value of a business interest to a particular investor with a given defined set of individual investment criteria. The criteria usually are stated as a compounded return expectation. Although this world does not necessarily contemplate a sale, that is the dominant reason for valuing a business interest in this world. Although similar in concept, there is a difference between investment value and market value. Exhibit 14.1 shows the salient differences.

The two worlds are connected; it is possible for them to derive the same value for a company. For instance, if PrivateCo is valued using the synergy subworld of market value, it is possible a particular buyer could have nearly identical investment criteria as the group of synergistic buyers. It is more likely, however, that the specific investor values an interest somewhere within the market value world but not exactly in one of the market value subworlds. There are many reasons why investment value might differ from market value, including these differences between the specific investor and the market:

- Risk perception of the investment and the required rate of return

- Synergies with the subject company

- Estimates of earnings and cash flow

- Capital structures

EXHIBIT 14.1 Differences between Investment Value and Market Value

| Investment Value World | Market Value World |

| Value attributable to one investor | Highest value available in the market |

| Derived based on a single investor | Derived based on likely investor “profiles” |

| Uses one investor return expectation | Uses return expectations of the investor profiles |

Exhibit 14.2 summarizes the longitude and latitude for investment value. To determine investment value, an investor begins with a return expectation, usually stated on an annually compounded basis, and then personalizes the benefit stream. For example, assume PrivateInvestor has a 25% return expectation and views PrivateCo's benefit stream as $2 million per year to the investor for the foreseeable future. Capitalizing the $2 million by 25% yields an investment value for PrivateCo of $7.5 million ($8 million less $500,000 long-term debt). Both the return expectation and the return generated by the investment are specific to PrivateInvestor.

EXHIBIT 14.2 Longitude and Latitude: Investment Value

| Definition | The value of a business interest to a particular investor. |

| Purpose | To determine the viability of an investment opportunity. |

| Function | To derive a value for the business interest based on a particular investor's estimate of the benefit stream and assessment of risk, probably for acquisition. |

| Quadrant | Empirical unregulated. |

| Authority | Investor. |

| Stream | Personalized to investor. |

| PRE | Personalized to investor. |

Quite often an investor becomes frustrated by an inability to complete transactions of private investment opportunities. Normally the investor does not bid high enough. The investor may be acting like an authority in a competing value world, such as market value. If the investor is relying on a business appraiser, that appraiser is likely thinking of and working in the fair market value world, not in the market value world. In these cases, the investor may not be successful until she modifies her valuation process to fit the value world where the investment is being transacted.

OWNER VALUE WORLD

The world of owner value measures the value of a business or business interest to the current owner. This world assumes the owner's current use of the interest and her ability to exploit the asset continue in the future unabated. Much like investment value, this world does not necessarily contemplate a sales transaction. The owner may need a value for reasons that cut across a number of value worlds. Owner value may incorporate the selfish motives of the owner and quite often involves a number of lifestyle issues.

EXHIBIT 14.3 Longitude and Latitude: Owner Value

| Definition | The value of a business interest to the owner. |

| Purpose | To determine the viability of an exit opportunity or measure return on the business investment. |

| Function | To derive a value for the business based on the owner's personal needs and unique perspective on the benefit stream and the risk. |

| Quadrant | Empirical unregulated. |

| Authority | Owner. |

| Stream | Personalized to owner. |

| PRE | Personalized to owner. |

Exhibit 14.3 describes the longitude and latitude for owner value. The first step in deriving owner value is to determine the benefit stream available to the owner. This stream is unique to every owner but has these common elements:

Although this definition of owner value benefit stream is liberal, it portrays the mentality of the typical owner-manager. By including all dollars in the stream that move in his direction, the owner generally values the business far beyond what it is worth to anyone else. Many owners also believe the risk of achieving and maintaining this stream is less than the market might measure. It is not unusual for an owner to use 10% to 20% as the capitalization rate in this situation, which often significantly understates the equity risk.

By way of example, assume Joe Mainstreet values PrivateCo's worth to him. He first calculates the company's benefit stream (some numbers are taken from Chapter 6):

| PrivateCo Benefit Stream | |

| Total compensation to owner, including bonuses | 450 |

| + Pretax earnings of the business | 1,800 |

| + Personal expenses passed through to the businessa | 75 |

| + Effect of close business contractsb | 9 |

| + Covered expenses such as insurances, business vacations, etc. | 25 |

| + Any other items that personally benefit the ownerc | 90 |

| Benefit stream to owner | 2,449 |

| aPersonal expenses equal vacations and conferences charged to company. bExcess rent charged to PrivateCo by a company controlled by Mainstreet. cTotal of donations ($74), legal ($9.9), and accounting ($6.5). |

|

The benefit stream to Joe Mainstreet is $2.45 million (as rounded). This is the amount Joe expects to receive or control each year for the foreseeable future. He is likely to capitalize this benefit stream at a low rate, because he believes achieving this stream is fairly certain. Assume Joe uses a 15% capitalization rate. This creates an owner value on a total capital basis of $16.3 million ($2.45 million divided by 15%). After deducting PrivateCo's long-term debt of $500,000, the value of the equity in the owner value world is $15.8 million.

Since owners tend to perceive the economic benefits and risk of ownership different from the general market, they often feel insulted by offers for their businesses. Given the built-in differences in opinion, it is amazing that deals ever happen with this group.

COLLATERAL VALUE WORLD

The collateral value world measures the amount a creditor is willing to lend with the subject's assets serving as security for the loan. A company enters the collateral value world when it seeks a secured loan (e.g., a commercial- or asset-based loan) or if it uses its assets in some financially engineered way (e.g., a sale-leaseback arrangement). Exhibit 14.4 summarizes the longitude and latitude for collateral value.

EXHIBIT 14.4 Longitude and Latitude: Collateral Value

| Definition | The value of a business interest for secured lending purposes. |

| Purpose | To determine how much a company can borrow using its collateral. |

| Function | To establish the borrowing base for a loan. |

| Quadrant | Empirical unregulated. |

| Authority | The lending industry. |

“Collateral” is defined as property that secures a loan or other debt so the lender may seize the property if the borrower fails to make proper payments on the loan. When lenders demand collateral for a secured loan, they are seeking to minimize the risks of extending credit. To ensure that the particular collateral provides appropriate security, the lender wants to match the type of collateral with the loan. For example, the useful life of the collateral typically will have to exceed, or at least meet, the term of the loan; otherwise, the lender's secured interest would be jeopardized. Consequently, short-term assets such as receivables and inventory are not acceptable as security for a long-term loan. They are, however, appropriate for short-term financing, such as a line of credit.

To further limit their risks, lenders usually discount the value of the collateral so they do not lend 100% of the collateral's highest value. This relationship between the amount of money a lender extends to the value of the collateral is called the loan-to-value ratio. Another term for loan-to-value ratio is the advance rate. Advance rates reflect the percentage of each asset class a lender actually will loan against. For example, a lender may advance 80% against eligible receivables, 50% against eligible inventory, and so on. Eligibility varies from lender to lender and is explained in detail in Chapter 20.

There is no single definition of “value” of an asset to be appraised in the collateral value world. Many definitions of value exist, and the use of each depends on the circumstances. Lenders may choose to have an asset valued at replacement cost, fair market value in continued use, fair market value removal, orderly liquidation value, or forced liquidation value, just to name a few. An asset appraiser is given the appropriate standard of value, usually by the lender, prior to the start of the appraisal. Definitions of a few of the standards are presented next.1

Fair value is “the cash price that might reasonably be anticipated in a current sale, under all conditions requisite to a fair sale. A fair value sale means that buyer and seller are each acting prudently, knowledgeably, and under no necessity to buy or sell, that is, other than in a forced or liquidation sale.”

Orderly liquidation value is “the estimated gross amount, expressed in terms of money, which could typically be realized from a sale, given a reasonable time to find purchasers, with the seller being compelled to sell on an as-is, where-is basis.”

This is the valuation standard most frequently used by asset-based lenders. Its primary attribute, “realized from a sale,” provides maximum flexibility to the presumed liquidator in both the timing and the method of disposal.

Forced liquidation value is “the estimated gross amount, expressed in terms of money, which could be typically realized from a properly advertised and conducted public auction sale, negotiated liquidation sale, or a combination of the two, with the seller being compelled to sell with a sense of immediacy, on an as-is, where-is basis, under present-day economic trends.”

The facts and circumstances of the appraisal determine the actual advance rate a lender might offer. Typically, however, the closer the standard reflects a cash position, the higher the advance rate. For instance, a lender might advance 80% against a forced liquidation appraisal but only 60% against an orderly liquidation value.

Success in the collateral value world can be enhanced in two ways. First, the borrower should confer with a lender prior to hiring an asset appraiser to ensure the correct standard of value is used. In some cases, an appraiser might appraise an asset using multiple standards. This causes the appraiser to employ a different appraisal process for each standard. Second, the more information a borrower provides to a lender, such as professional asset appraisals, the more likely a positive result will occur, especially regarding advance rates.

The type of collateral used to secure the loan affects the lender's advance rates. For example, unimproved real estate yields a lower advance rate than improved occupied real estate. These rates vary among lenders, and lending criteria other than the value of the collateral may influence the rate. For example, a healthy cash flow may allow for more leeway in the rate. A representative listing of advance rates for different types of collateral at a typical secured lender is shown in Exhibit 14.5. This represents the method for determining the asset value that is then multiplied by the advance rate.

EXHIBIT 14.5 Typical Advance Rates

| Asset | Advance Rate | Type of Value |

| Real estate | ||

| Occupied | 80% | Appropriately appraised value |

| Improve, not occupied | 50% | Appropriately appraised value |

| Vacant and unimproved | 30% | Appropriately appraised value |

| Inventory | ||

| Raw materials | 50%–60% | Eligible amount |

| Work-in-process | 0% | |

| Finished foods | 50%–60% | Eligible amount |

| Accounts receivable | 70%–80% | Eligible amount |

| Equipment | 65%–85% | Purchase price |

Margined collateral is the result of an advance rate applied against a qualifying asset. A borrower's total margined collateral value is calculated by applying the advance rates against qualifying asset groups. Exhibit 14.6 shows PrivateCo's calculations.

EXHIBIT 14.6 PrivateCo Collateral Value ($000)

The “stated value” for each of the asset classes is taken from PrivateCo's balance sheet, as shown in Chapter 5. The “loanable value/fair market value” column shows the amounts eligible for secured lending. Accounts receivable are reduced from the stated value to reflect ineligible receivables, such as past dues or those due from related companies. Inventory is reduced to account for work-in-process inventory, which is not eligible for secured lending. Land, buildings, machinery, and equipment are adjusted to their fair market values. These changes are explained in Chapter 5.

Finally, margined collateral value is the sum of the various margined asset classes. For PrivateCo, margined collateral value equals about $2.5 million (as rounded). Financial ratios and earnings further determine the amount PrivateCo actually can borrow. Chapters 17 and 20 describe collateral issues in much more detail.

EARLY EQUITY VALUE WORLD

The early equity value world describes the valuation process for early round investors. The early equity world is the domain of venture capitalists (VCs) and angel investors but also applies to any investor who gets in on the ground floor of a business opportunity. Exhibit 14.7 summarizes the longitude and latitude for early equity value. Traditional valuation metrics may not apply to start-ups. There are no earnings, so all historical income-based methods are out. Future forecasts for the company are typically so rosy that valuation decisions based on them become difficult. Normally there are not enough tangible assets to make a meaningful asset-based valuation. It may be possible to look to the market for like-kind start-ups, but this information normally is not available. Faced with this valuation dilemma, most early-stage investors back into the valuation based on an assumed terminal value.

EXHIBIT 14.7 Longitude and Latitude: Early Equity Value

| Definition | The value of a business interest as a start-up. |

| Purpose | To determine how much a company is worth to an early investor. |

| Function | To determine equity splits for the early investors. |

| Quadrant | Empirical unregulated. |

| Authority | The venture capital industry. |

| Stream | Cash distributed plus cash terminal value. |

| PRE | 37.5%. |

EXHIBIT 14.8 Example Venture Capital Investment

| Up-front investment | $ 5.0 million |

| Subject year 5 earnings | 12.4 million |

| Projected selling multiple | 5.0 |

| Projected enterprise selling price in year 5 | $62.0 million |

| Venture capitalist requirement in year 5 to obtain a 35% compounded rate of return | $22.4 million |

| Proposed VC equity split | 36% |

Terminal value represents the expected value of the investment at the point of exit. Most early investors have five- to seven-year investment horizons, so terminal value is the value of their investments at that point. The return to the investor becomes the terminal value plus any distributions or dividends received along the way. Most early investors do not expect distributions before the exit event because it is generally assumed the company will need to reinvest the cash to grow. VCs win or lose the investment game based on accurately picking companies with terminal values that meet or exceed their required rates of return. Estimating the terminal value enables the VC to back into the value of the company and then decide equity splits. Equity splits are the percentages of the company each investor owns.

Exhibit 14.8 shows the assumptions and equity split determination for a typical VC investment. Suppose a VC invests $5 million today in the equity of a business. The VC expects a 35% compounded rate of return over a five-year investment life. The VC needs to receive $22.4 million in year 5 to achieve its desired return. By employing conservative forecasts, managements believe the company will earn $20 million per year by its fifth anniversary. The VC firm does its own calculations and thinks the company will earn $12.4 million by the end of the fifth year. Further, the VCs believe the company will sell for five times earnings. This suggests an enterprise value of the company of $62 million in year 5 ($12.4 million × 5). The VC then backs into the required equity split of 36% (($22.4 million ÷ $62 million) × 100).

Early investors may request more or less equity depending on their calculations of the likelihood and amount of the exit value. Considering these numbers, it is easy to see why so many VC and other early investments fail to deliver expected returns.

BANKRUPTCY VALUE WORLD

When a business is unable to service its debt or pay its creditors, the business or its creditors can file with a federal bankruptcy court for protection under either Chapter 7 or Chapter 11. In Chapter 7, the business ceases operations. A trustee sells all of its assets and then distributes the proceeds to the business's creditors. Any residual amount is returned to the owners of the company. In Chapter 11, the debtor usually remains in control of its business operations as a debtor in possession and is subject to the oversight and jurisdiction of the court.

Exhibit 14.9 summarizes the longitude and latitude for bankruptcy value.

EXHIBIT 14.9 Longitude and Latitude: Bankruptcy Value

| Definition | The value of a business in a bankruptcy proceeding. |

| Purpose | To derive a value that is in the best interests of the bankruptcy estate and its creditors. |

| Function | To determine how much value the creditors will receive in the proceeding. |

| Quadrant | Empirical regulated. |

| Authority | Bankruptcy judge. |

| Stream | Not meaningful. |

| PRE | Not meaningful. |

Recently 363 bankruptcy sales have become common. These sales, named after the section of the bankruptcy code dealing with the procedure, allow for a sale of assets more quickly than in a plan of reorganization. A 363 sale requires only the approval of the bankruptcy judge, while a plan of reorganization must be approved by a substantial number of creditors and meet certain other requirements to be confirmed. A plan of reorganization is much more comprehensive than a 363 sale in addressing the overall financial situation of the debtor and how the company's exit strategy from bankruptcy will affect creditors.

In a 363 sale, the assets will be conveyed to the purchaser free and clear of any liens or encumbrances. Those liens or encumbrances then will be attached to the net proceeds of the sale and paid as ordered by the bankruptcy court. Before approving a sale, the bankruptcy court must answer these questions:

- Do the terms of the sale constitute the highest and best offer for the assets to be sold?

- Were the negotiations concerning the terms and conditions of the proposed sale conducted at arm's length?

- Is the sale in the best interests of the bankruptcy estate and its creditors?

- Has the purchaser acted in good faith and is the sale itself being made in good faith?

All of these questions must be answered yes or the sale will not be approved. The bankruptcy judge is the authority in this world, as she presides over the case to determine if the requirements for approval of a 363 sale have been met.

Valuation in a 363 sale may begin with a stalking horse bid. A stalking horse is an interested buy who makes an initial bid for the bankrupt company's assets. Doing this can put prospective purchasers in a risky position, so they usually negotiate to receive a breakup or topping fee if they do not become the approved purchaser. This ensures that another party must bid significantly more than the initial prospective buyer did to buy the company's asset or assets. This overbid is sometimes called an upset bid.

Bidding procedures are proposed by the debtor concerning the process and form by which offers, if any, for the asset or assets to be sold should be made by parties other than the stalking horse. Often they are included as part of the 363 motion as a means of keeping the process orderly. Sometimes, however, other prospective purchasers see the bidding procedures as designed to cool competing offers by imposing onerous procedural requirements.

A credit bid occurs when a secured creditor can bid up to the amount of the debt owed to it by the debtor for the purchase price of the assets to be sold without having to pay any actual cash.

The bankruptcy value world is highly structured in that its authority— judges—have almost absolute power to administer and sanction behavior in their world.

PUBLIC VALUE WORLD

Public companies, especially those with floats of more than $500 million, comprise the public value world. Public investment bankers are the valuation authorities in this world. They use market knowledge to determine the price for initial offerings, secondary offerings, and, to some degree, pricing for mergers and acquisitions.

Exhibit 14.10 summarizes the longitude and latitude for bankruptcy value.

EXHIBIT 14.10 Longitude and Latitude: Public Value

| Definition | The value of a business in the public markets. |

| Purpose | To derive a value of a public company. |

| Function | To determine the price of a stock in an initial public offering or secondary offering. |

| Quadrant | Empirical regulated. |

| Authority | Public investment bankers. |

| Stream | Net income. |

| PRE | Price/earnings ratio. |

Valuing public equities primarily uses two approaches: discounted cash flow (DCF) and fundamental (market comparison) analysis. Free cash flow valuation and comparables (comps) are key tools in fundamental analysis, the process of picking stocks that are undervalued by the stock market. An analyst attempts to discover and acquire stocks of companies that are undervalued in anticipation that other investors eventually realize the company's true value.

The process of valuing publicly traded equity using DCF involves three steps.

1. Pro forma statements are forecasted several years into the future.

2. The forecasted statements are used to calculate free cash flows for the entire company. These free cash flows are then discounted by the cost of capital for the company.

3. The equity value of the common stock is calculated as total company value minus the market value of its debt. Dividing that value by the number of outstanding shares produces the value of one common share. The resulting value of the shares can be compared with the current market price to make buy and sell decisions.

Fundamental stock analysts rely heavily on price/characteristics ratios using comparable companies to validate buy and sell decisions. Most of these ratios—for example, the price/earnings (P/E) ratio—include the quoted market price in the numerator and some measure of profitability or performance in the denominator. The analyst compares the ratio of the stock in question to the ratios for stocks of companies in the same industry and of similar size and financial leverage. The comparison tells the analyst if the stock is expensive or cheap relative to other stocks.

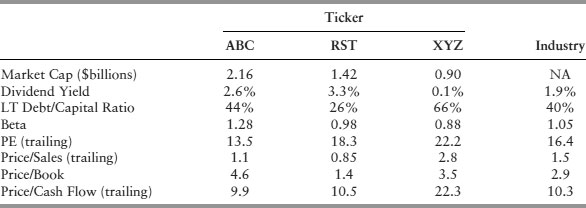

Assume Joe Mainstreet is considering taking PrivateCo public via an initial public offering. Joe engages Jerry Smith of PubIBankers to value PrivateCo. Jerry uses fundamental analysis to determine how the public market of investors would value PrivateCo. He develops Exhibit 14.11, which shows financial metrics of comparable companies. The ideal set of comparable companies will be from the subject's industry and will have financial policies, including dividend yield and financial leverage, similar to the company being valued. The companies shown in the exhibit are hypothetical. For this discussion, assume they would be reasonable candidates for comparison with PrivateCo. The companies vary in size, dividend policy, and financial leverage.

EXHIBIT 14.11 Price/Characteristic Ratios for Comparable Companies

The most popular characteristic ratio for comparison across stocks is the P/E ratio. But Jerry would also analyze growth rate comparisons, quality of earnings, as well as the other financial metrics. Assume Jerry completes his analysis and determines the public markets would value PrivateCo's after-tax earnings at 11 times on a control basis. PrivateCo's pro forma earnings must be calculated by starting with pretax earnings and then adjusting for seller discretionary expenses, one-time expenses, and taxes. Exhibit 14.12 shows these calculations.

EXHIBIT 14.12 PrivateCo Pro Forma Earnings ($000)

| Item | Y/E 20X3 |

| Pretax Earnings | $1,800 |

| Adjustments | |

| Excess Owner Compa | 250 |

| Management Feesb | 200 |

| Interestc | 95 |

| Officer Insurancesd | 5.0 |

| Excess Accountinge | 6.5 |

| Excess Legalf | 9.9 |

| Excess Rentg | 8.7 |

| Excess Health Insurance | 8.2 |

| Casualty Loss—Fireh | 35 |

| One-time Consultingi | 0 |

| Donationsj | 74 |

| Employee Incentivesk | 125 |

| Total Adjustments | 817 |

| Pro Forma Pretax Earnings | $2,617 |

| Less corporate taxesl | (915) |

| Pro Forma Net Earnings | $1,702 |

| aSince the majority owner is passive, all his compensation will be added back.

bManagement fees are charged each year by another company that the majority owner also controls. cInterest expense is added back to depict cash flow accurately. dOfficer insurance expenses are added back since the majority shareholder will not be on the payroll after the sale. eSome accounting services are performed by another company the majority owner controls and are billed to PrivateCo. fOne-time expense. Former employee illegally took blueprints and PrivateCo successfully sued that person. gAssumes current rent will not continue under new ownership. hThe uninsured part of a fire (one-time expense). iA consultant was hired to perform design studies for a new product, which was not produced. jThe company gives donations each year to a charity the majority owner supports. kEmployee incentives includes bonuses that only a passive shareholder would pay. lAssume corporate income taxes equal 35% of pretax earnings. |

|

Jerry calculates PrivateCo's trailing pro forma net earnings as $1.7 million. Multiplying this amount by the 11 multiple just noted produces an enterprise value of $18.7 million. Once again, PrivateCo's $500,000 debt must be subtracted from this enterprise value to determine a 100% equity value. Thus, the equity value of PrivateCo in the public value world is $18.2 million.

Literally thousands of books have been written on valuing companies in the public value world. Readers who need more detail are encouraged to review that literature.

TRIANGULATION

Each of the value worlds discussed in this chapter deserves a separate triangulation discussion.

The investment value world lies in the empirical unregulated quadrant. The investor is the authority in this world. This world is empirical because investors observe acquisitions in the highly unregulated open market. This world's link to capital is dependent on the investor and the deal opportunity. An investor generally brings some level of equity to a transaction, along with managerial and other financial capabilities. The target usually supplies most of the collateral for debt capacity. By its nature, this world is transfer-oriented. Many transfer methods, such as auctions, recapitalizations, and management buy-ins, are available to the investor. The more capabilities an investor brings to a deal, the more sources of capital and transfer methods are accessible.

An owner in the owner value world is the ultimate authority. Owners make all the rules for other interested parties to follow. This is one reason why many owners are loath to use banks as a capital source. Banks restrict the owner's actions, something to be avoided by this control-oriented group. Transferring a business is difficult for this group. Owners tend to view their companies as generating higher benefit streams than most outsiders do. Plus, since managing risk is an integral part of their everyday lives, owners see less risk in achieving the benefit streams than other observers do. These two facts often make it unlikely, from the owner's perspective, that the business will be valued for a fair price. Ultimately, many owner-managed businesses transfer only upon the earlier of two events: The owner is able to appreciate other value worlds, or she gets desperate to sell.

A strong authority also rules the collateral value world. Secured lenders invoke the golden rule (he with the gold makes the rules) in their dealings with borrowers. Lenders set the terms by which they will lend. While flexible around the edges, they tend to value assets in a way that favors them. Collateral value is the dominant world in private capital formation because it is the most pervasive level of capital. Banks, asset-based lenders, and even some mezzanine lenders live in this world. Nearly all transfer methods are available to collateral value. In fact, most transfers start is this world.

Venture capitalists, for whom the golden rule is sacrosanct, are the primary authorities in the world of early equity. In this world, the authority values, capitalizes, and transfers private business interests. While it is an unregulated world, the veto power of VCs is very strong. They can choose not to invest. Because this is an extremely high-risk/high-return world, a high level of potential is necessary to attract early investment.

Bankruptcy judges are the authority in the bankruptcy value world. Valuation in this world is discovered based on a formal bidding process. Many sales occur in bankruptcy using the 363 section of the law. This section provides a quicker resolution to the process, thus possibly saving jobs. This is a highly regulated world.

Large public companies make up the public value world. Public investment bankers are the authorities in this world. Values in this world are determined mainly by analyzing what investors are paying for comparable companies.

| World | PrivateCo Value |

| Asset market value | $2.4 million |

| Collateral value | $2.5 million |

| Insurable value (buy/sell) | $6.8 million |

| Fair market value | $6.8 million |

| Investment value | $7.5 million |

| Impaired goodwill | $13.0 million |

| Financial market value | $13.7 million |

| Owner value | $15.8 million |

| Synergy market value | $16.6 million |

| Public value | $18.2 million |

NOTE

1.American Society of Appraisers, Definitions of Values Relating to Machinery, www.appraisers.org.