CHAPTER 17

Bank Lending

There are a variety of senior lenders in the marketplace. This group typically has a first, or senior, position in the collateral pool of a company. Commercial banks, the primary players in this group, are the focus of this chapter. Owner-managers are motivated to seek bank lending for several reasons. Banks historically have been the largest source of capital for small to medium-size businesses. Banks also typically have been the cheapest source of borrowed funds. Over the past 15 years, banks have broadened their offerings to include a spectrum of financial alternatives appealing to owners in need of more sophisticated services. Banks now serve as financial intermediaries. They lend, arrange, advise, and directly invest capital in private companies.

Bank credit is rationed based on the return needs of the institution. Banks seek to maximize the spread between deposits received and income-producing assets. Business lending is an example of the latter. Banks lend to small businesses only when it is likely that the loans will be repaid. Credit quality is enhanced by sophisticated underwriting techniques, such as credit scoring for individual loans and repayment projections for commercial loans. Even with these methods, lending to small businesses remains risky. This fact in part explains banks’ hierarchical decision-making structures. Most banks require a handful of bank officer signatures on the loan request as an experiential hedge against this risk.

This chapter describes the types of loans banks extend, interest rate options and hedges, loan costs, loan covenants, risk ratings, and negotiating points to consider. Exhibit 17.1 provides a snapshot of bank lending.

TYPES OF FACILITIES

Most banks offer loans such as term loans, credit lines, and letters of credit, although the terminology may change from bank to bank. Banks frequently offer government-sponsored loans, the subject of the next chapter. The next sections discuss each type of bank loan with an emphasis on required collateral and payment terms.

Term Loan

Term loans are used most often to finance fixed-asset purchases, such as equipment, vehicles, furniture, and fixtures. They also can be used to finance permanent working capital or debt consolidation. Term loan features include:

EXHIBIT 17.1 Capital Coordinates: Bank Lending (Credit Line)

|

|

| Capital Access Point | Credit Line |

| Definition | A credit line allows a company to borrow against an established credit limit to meet short-term working capital needs. There are various costs for a credit line in addition to the stated interest rate. Borrowers should consider closing points, compensating balances, unused line fees, and float days as additional costs of the loan. The credit box for a credit line requires a borrower to possess sufficient collateral and cash flow to service the loan. |

| Expected Rate of Return | 9.0% |

| Likely Provider | Banks |

| Value World(s) | Collateral value |

| Transfer Method(s) | Credit lines may be involved with any or all transfer methods. |

| Appropriate to Use When . . . | A borrower's cash flow fluctuates within a month or season, causing short-term working capital needs. Credit lines should be used only when the capital need is also short term. |

| Key Points to Consider | Banks are less obtrusive to healthy borrowers than most other capital providers. Financial reporting is periodic and not as demanding. A credit line may or may not provide adequate growth capital. Credit lines are usually for fixed amounts and are not intended to mirror a company's growth curve. Many banks require an annual cleanup period where the credit line must be reduced to zero for at least one month. |

- A choice of a fixed or variable interest rate, which is discussed later.

- Various terms to meet borrowers’ needs. Usually terms are no more than five years with the exception of commercial real estate loans that offer longer terms.

- The advantage of spreading the cost of the fixed asset over its useful life, providing the borrower with a manageable monthly payment.

Term debt is collateralized by a first lien on the current and long-term assets of the company. Because term loans have specific time and terms, repayment must be made within the useful life of the financed asset.

Credit Line

A credit line allows a company to borrow against an established credit limit for short-term working capital. Borrowings are payable on demand, and interest rates usually are tied to an index, such as the prime rate. A credit line can be secured or unsecured. If the line is secured, the collateral base is comprised of “short-term” assets, such as receivables or inventory. Credit lines are subject to review at least annually.

These loans enable a company to borrow up to a specified amount of money whenever it is needed. The company pays interest on the money it actually borrows, instead of the committed amount. Some banks charge commitment fees and unused line fees, but these are negotiated up-front between the bank and the borrower. A typical line of credit is seasonal, in that it helps to supply a company's seasonal cash needs. Seasonal lines usually require a company to pledge specific assets, such as receivables and inventory, to collateralize the loan.

Letter of Credit

A letter of credit (L/C) is a written agreement issued by a bank and given to the seller (exporter) at the request of the buyer (importer) to pay up to a stated sum of money. The L/C is good for a stated period of time (the expiration date) and is payable upon presentation of stipulated documents. Payment may be made immediately or after a specified period of time. In effect, the issuing bank is substituting its credit for that of the buyer. Since an experienced bank has a broad correspondent base, the letter of credit can travel directly from the buyer's bank to the exporter's bank without passing through multiple banks.

If the buyer requests a letter of credit from its bank, it is granted only if the buyer has established an adequate line of credit with the bank. On behalf of the buyer, the bank then promises to pay the purchase price to a seller, or the seller's appointed bank, if the stipulated and highly detailed conditions are met. Example conditions include complete shipment, onboard, ocean bills of lading, a commercial invoice and original packing slip, and proof of adequate insurance.

An element of L/Cs that surprises novice users is the attention to detail required. There is no item too small to consider. Export managers learn to take great care to correct every misspelling in original documents. Some banks use whatever excuse possible to delay processing documents while holding their customers’ money.

L/Cs are available in a variety of forms. Some of these are confirmed irrevocable L/Cs, confirmed L/Cs, and acceptance L/Cs. Irrevocable L/Cs are the most common form.

Collateral

Collateral is property that secures a loan, or other debt, so the lender may seize the property if the borrower fails to make proper payments on the loan.

When lenders demand collateral for a secured loan, they are seeking to minimize the risks of extending credit. To ensure the collateral provides appropriate security, the lender matches the type of collateral with the loan being made. For example, the useful life of the collateral typically needs to meet or exceed the term of the loan, or the lender's secured interest would be jeopardized. Consequently, short-term assets, such as receivables and inventory, are not acceptable as security for a long-term loan, but they may be appropriate for short-term financing, such as a line of credit.

In addition, many lenders require their claim to the collateral in the form of a first-secured interest. This means no prior or superior liens exist, or may be subsequently created, against the collateral. As a priority lien holder, the lender ensures its share of any foreclosure proceeds before any other claimant.

Lenders further limit their risks by discounting the value of the collateral and not lending 100% of the collateral's highest value. This relationship between the amounts of money a lender extends and the value of the collateral is called the loan-to-value ratio, also known as advance rates. Advance rates reflect the percentage of each asset class a lender actually will loan against. For example, a lender may advance 80% against eligible receivables, 50% against eligible inventory, and so on. Eligibility varies from lender to lender and is explained in detail in Chapter 20.

The type of collateral used to secure the loan affects the lender's advance rates. For example, unimproved real estate yields a lower advance rate than improved occupied real estate. These rates vary between lenders, and lending criteria other than the value of the collateral may also influence the rate. For example, a healthy cash flow may allow for more leeway in the rate. A representative listing of advance rates for different types of collateral at a typical secured lender is shown in Exhibit 17.2. The type of value represents the method for determining the asset value that is then multiplied by the advance rate.

EXHIBIT 17.2 Typical Advance Rates

| Asset | Advance Rate | Type of Value |

| Real Estate | ||

| Occupied | 80% | Appraised value |

| Improved, not occupied | 50% | Appraised value |

| Vacant and unimproved | 30% | Appraised value |

| Inventory | ||

| Raw Materials | 50%–60% | Eligible amount |

| Work-in-process | 0% | |

| Finished goods | 50%–60% | Eligible amount |

| Accounts receivable | 70%–80% | Eligible amount |

| Equipment | 75%–85% | Purchase price |

Margined collateral is the result of an advance rate applied against a qualifying asset. A borrower's total margined collateral value is determined by applying advance rates against qualifying asset groups.

Loan Payments

Loan repayment schedules are highly negotiable based on the needs of the parties. However, borrowers sometimes forget that the longer it takes to pay back the principal. the higher the total interest payment will become. Some payment options are:

- Equal payments. This type of loan requires the borrower to pay the same amount each period (monthly or quarterly) for a specified number of periods. Part of each payment is applied to interest, and the balance is applied to principal. The loan is fully repaid after the specified number of periods.

- Equal payments with a final balloon payment. This type of loan requires the borrower to make equal monthly payments of principal and interest for a relatively short period of time. After the last installment payment, the borrower must pay the balance in one payment, called a balloon payment.

- Interest-only payments and a final balloon payment. With this type of loan, the borrower's regular payments cover only interest. The principal is unchanged. At the end of the loan term, the borrower makes a balloon payment to cover the entire principal and any remaining interest. Borrowers often prefer this payment structure because of the lower periodic payments. However, borrowers ultimately pay more interest because they are borrowing the principal for a longer time.

- Equal principal payments. This type of loan requires the borrower to pay the same amount of principal each period for a specified number of periods. The total payment for each period is variable, and it should decline as the borrower pays interest only on the outstanding principal at the beginning of the period. With this payment structure, borrowers pay larger payments at the beginning of the loan.

INTEREST RATES

Most business borrowers still associate interest rates with the prime rate, the rate banks have historically charged their most creditworthy customers. Over the past decade or so, however, the prime rate has given way to different market indices, such as LIBOR (London Interbank Offered Rate) and swap rates. There are two options to set interest rates:

1. Fixed rate. With a fixed-rate loan, the interest rate applied to the outstanding principal remains constant throughout a predetermined period that may or may not equal the length of the loan. The interest rate is set at the beginning of a loan by examining the risk involved and the current market rates. The advantage of a fixed-rate loan is that the interest rate is fixed. The payments are constant and will not rise if the market rate rises. But the borrower does not benefit from a decline of the market rate. Many lenders will incorporate prepayment penalties into their loan terms to protect yield. As an aside, some banks will quote fixed interest rates using a 360-day year, which helps to increase the bank's yield.

2. Variable interest rate. With a variable interest rate, the interest rate applied on the outstanding principal amount fluctuates in line with changes to the prime rate or LIBOR and, as a result, so will the amount of the borrower's payments. The interest rate for each period is the current market rate plus a predetermined premium, which remains constant during the life of the loan. With a variable interest rate loan, the borrower saves money when the market rate decreases. The disadvantage, however, is the interest the borrower pays will increase with the market rate.

Fixed Rates

Most banks will not offer loans with fixed interest rates for a term longer than five to seven years because its cost of funds may increase significantly above the fixed rate on the loan. However, banks can “match funds” by locking in a rate on a certificate of deposit or other liability for the same amount and term as the loan.

Variable Rates

Banks may offer many different types of “floating” interest rates. Some of the more common are:

- Prime rate. Most banks follow the lead of the major money center banks in setting their own prime rates. Unless the borrower's loan agreement specifies “New York prime,” a bank's prime rate may be different from the prime announced by such money center banks. Furthermore, increases or decreases in a borrower's rate may lag the market leaders by a day, a weekend, or even longer. Most banks define their prime rate as the rate of interest established by the bank from time to time whether or not such rate shall be otherwise published. The borrower's loan agreement also specifies how quickly its rate changes after prime changes. Usually it is immediately, but sometimes it is not until the first of the next month.

- LIBOR. LIBOR is the rate on dollar-denominated deposits, also known as Eurodollars, traded between banks in London. The index is quoted for one month, three months, six months, or one-year periods. LIBOR is the base interest rate paid on deposits between banks in the Eurodollar market. A Eurodollar is a dollar deposited in a bank in a country where the currency is not the dollar. The Eurodollar market has been around for decades and is a major component of the international financial market. London is the center of the Euromarket in terms of volume.

The LIBOR rate quoted in the Wall Street Journal is the LIBOR posted by the British Bankers’ Association (BBA). Each day the Wall Street Journal publishes the prior day's BBA LIBOR rate as part of the Money Rates table in the Money and Investing section. - Swap rates. Swap rates are derived from interest rates set in derivative contracts, or swaps, which trade every day in the multitrillion-dollar international market. Although a swap can take many complex forms, the transaction is fundamentally an agreement between two parties to exchange short-term interest payments for long-term interest payments, or vice versa. Each party agrees to assume the interest rate payments of the other's loan, based on the particular party's desire to hedge its interest rate risk. The fixed rate, of 1 to 30 years, that the floating rate borrower has assumed is his “swap rate.” The Federal Reserve publishes average swap rates for appropriate fixed-term periods. Because the parties involved in such swaps are high-grade corporate and municipal entities, swap rates represent an active and liquid schedule of rates between highly creditworthy institutions.

As an example, suppose a borrower has a seven-year commercial mortgage tied to one-month LIBOR. The company is concerned about rate volatility during the life of the loan. The borrower decides to swap its floating rate for a fixed rate to mitigate the risk. In the swap transaction, the company pays a fixed rate of 3% to its swap counterpart, SwapCo, in exchange for receiving LIBOR. The swap cash flows are based on a principal schedule matching the outstanding loan. In other words, the LIBOR payment the company receives from SwapCo offsets the LIBOR payment the company owes to its lenders.

Note that the borrower has engaged in two separate transactions: a loan and a swap. In the loan transaction, the company is making floating-rate interest payments (LIBOR plus borrowing spread) to its lenders. In the swap transaction, the company is making or receiving payments based on the difference between LIBOR and the swap rate. The borrower, in effect, has created a fixed rate on the loan and is immunized against movements in LIBOR.

LIBOR versus Prime

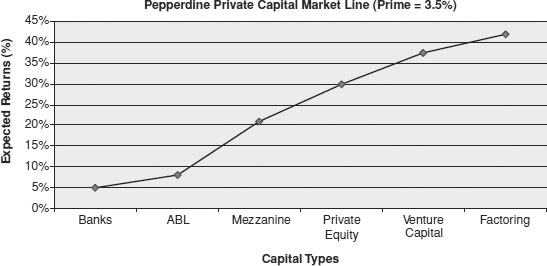

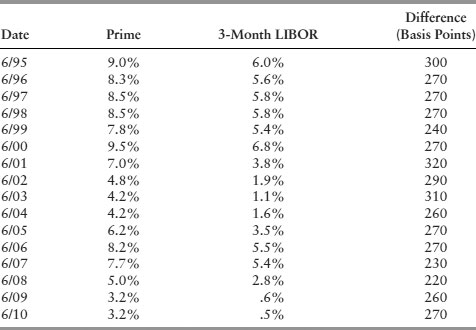

Historically, the LIBOR interest rate has been much lower than the prime rate. As Exhibit 17.3 shows, since 1995, the difference ranged from 220 to 320 basis points (bps; a basis point is .01%).1

EXHIBIT 17.3 Prime versus LIBOR Rates

LIBOR is usually priced in the marketplace at some premium, such as +200. This means the quoted rate is LIBOR plus 200 bps (or LIBOR plus 2%). This raises the question whether LIBOR with a premium is actually cheaper than borrowing at prime. At least one study has shown that it is cheaper. The study conducted by the Loan Pricing Corporation found that prime borrowing is more expensive by roughly 125 to 150 bps. This difference is known as the prime premium. The study also shows that the added volatility of LIBOR does not account for difference. In other words, even with the added risk of greater LIBOR rate swings, which are more intense than prime in the near term, it is still substantially cheaper to borrow at LIBOR.2

Economists claim that markets eventually correct an imbalance. Why has the prime premium not been reduced or eliminated? The main reason involves competition. Historically, LIBOR borrowers were public companies with the ability to issue commercial paper or public bonds. These companies had established credit ratings, and the spread above LIBOR represented a premium for default risk only. Prime-based lending, however, adds additional spread to pay for the cost of investigating and monitoring privately owned borrowers. With increased competition, lenders have chosen to introduce LIBOR pricing to the private sector apparently without getting paid for the added cost of fully monitoring these borrowers.

Competitive pressure increasingly will lead to long-term stability in the spread between prime and LIBOR. The cost of capital for most major lenders is similar, leading to similar consumer interest rates. Since most lenders publish the interest rates they charge, there is little reason for one major lender to undercut the others on price, since it knows that the others will quickly match rates. Any advantage will be short-lived. Aside from branding, marketing, and other secondary factors, debt is a commodity. Since money is fungible, it matters less on who the lender is, and more on the general health of companies so they can afford to repay the loans.

But interest rates can be managed by employing sophisticated hedging techniques, as discussed next.

INTEREST RATE HEDGES

There are methods by which interest rates can be hedged, or controlled, by the borrower for a price. Due to the complexity of some of these strategies, some techniques may be limited to accredited investors. Three hedging techniques are shown here: cap, collar, and lock.

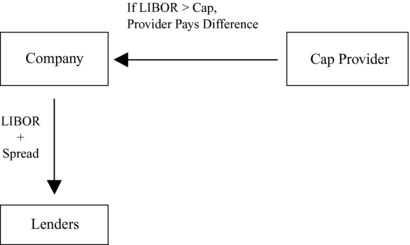

Interest Rate Cap

An interest rate cap is used by companies to set a maximum interest rate they will pay on their borrowings. Exhibit 17.4 illustrates an interest rate cap. If the floating rate rises above a cap level, the company is credited for the difference. If the floating rate remains unchanged or declines, the company benefits from lower borrowing rates. The cap is purchased with a one-time up-front fee, usually referred to as a premium. Typically a cap can be purchased for a minimum of 90 days and a maximum term of five years. Once the premium is paid, there are no other costs or risks associated with the hedge.

EXHIBIT 17.4 Interest Rate Cap

As an illustration, suppose PrivateCo has a $20 million, two-year revolving credit facility tied to LIBOR. Core outstandings are $12.5 million. PrivateCo uses one-month LIBOR, assumed at 3.5%, as its primary borrowing index. For planning purposes, the company has assumed that LIBOR will not rise above 4.5%.

Without any hedge, PrivateCo is vulnerable to rising rates. To protect its projections, PrivateCo decides to purchase a cap on one-month LIBOR at 4.5%. The contract will cover a core amount of $12.5 million. PrivateCo pays an initial premium for two years of protection. If LIBOR rises above 4.5% during the two-year contract period, PrivateCo will be reimbursed by the cap provider for the difference.

Interest Rate Collar

Borrowers use interest rate collars to set the minimum (floor) and maximum (cap) interest rates they will pay on their borrowings. Exhibit 17.5 illustrates an interest rate collar. If the floating rate rises above the cap level, the company is credited for the difference. If the floating rate falls below the floor level, the company is debited for the difference.

EXHIBIT 17.5 Interest Rate Collar

EXHIBIT 17.6 Forward Rate Lock

By way of example, suppose PrivateCo just completed a midsize acquisition financed with a syndicated bank credit facility. The facility is a $25 million, six-year combined reducing revolving credit and term loan with LIBOR pricing. The financing includes a 50% hedge requirement for a minimum term of three years.

PrivateCo and its lenders have agreed that the maximum LIBOR rate threshold to support cash flow projections is 3.5%. Management believes that three-month LIBOR, currently (in this example) at 2.5%, is headed higher over the foreseeable future but eventually may reverse course. PrivateCo enters a $12.5 million, three-year collar with a cap of 3.5% and a floor of 1.5%. If during the three-year collar agreement period LIBOR rises above 3.5%, PrivateCo will be reimbursed by the collar provider for the difference. If LIBOR declines below 1.5% to, say, 1.0%, PrivateCo will owe (1.5% – 1.0%) = .50% on the collar.

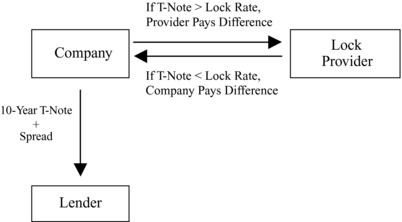

Forward Rate Locks

Forward rate locks enable a company to borrow at a certain interest rate at a specified date in the future. Exhibit 17.6 illustrates a forward rate lock. On the specified future date, if the actual interest rate is higher than the lock rate, the company is credited for the difference. If the actual interest rate is lower than the lock rate, the company is charged for the difference.

As an example, a forward rate lock is often used by a company to hedge a future borrowing need. For example, suppose management of PrivateCo believes it will need to borrow heavily in the next 90 days but that interest rates may spike upward during this period. Further, assume that PrivateCo borrows at the prime rate, and this rate currently is 3.5%.

To protect against an increase in rates, PrivateCo enters into a forward lock agreement with BankCo for three months forward at a fixed rate of 3.5%. In three months, PrivateCo would borrow the anticipated funds at a variable rate. If the prime interest rate at that time was higher than 3.5%, BankCo would compensate PrivateCo for the difference in rates, and vice versa.

LOAN COVENANTS

Loan covenants are used by lending institutions to influence borrowers to comply with the terms in the loan agreement. If the borrower does not act in accordance with the covenants, the loan may be considered in default and the lender may have the right to demand payment in full. Loan agreements between banks and customers generally contain several types of covenants: Affirmative covenants require the borrower do certain things; negative covenants restrict the borrower in some way; and financial covenants require the borrower to maintain certain financial characteristics during the term of the loan agreement.

Affirmative covenants generally require the borrower to comply with basic rules. Examples of affirmative covenants include:

- Maintain legal existence.

- Stay current with all taxes.

- Maintain appropriate insurances.

- Keep an accurate financial reporting system.

- Provide the bank with reports as required.

- Possibly maintain compensating balances with the bank.

Negative covenants usually restrict the actions of the corporation and ownership. Examples of negative covenants include:

- Limits to level of indebtedness.

- Limits to distributions, dividends, or management fees.

- Do not merge with or acquire another company.

- Do not allow other liens on company assets.

- No changes in ownership.

- Restrict corporate guarantees.

Financial covenants measure company ratios against projections the management provided before or during the loan process. Examples of financial covenants include:

- Maintain a current ratio (current assets divided by current liabilities) of not less than 1.5 to 1.

- Maintain tangible net worth in excess of $1 million.

- Maintain a ratio of total liabilities to tangible net worth of no greater than 3 to 1.

Covenant requirements can be extensive, depending on the amount and term of the loan and the credit standing of the borrower. Most banks monitor compliance with loan covenants on a quarterly basis with the receipt of quarterly and annual financial statements. Sometimes the bank requires a periodic certification by a corporate officer or independent accountant that no covenant violation has occurred, called a compliance certificate.

HOW BANKS DEAL WITH COVENANT VIOLATIONS

Banks take loan covenants quite seriously and generally are careful to watch for violations. Sometimes violations may go undetected, but once they are detected, the bank may:

- Waive the provisions of the violated covenant for a certain period of time. This waiver period generally lasts for up to one year, at which time the covenant would be in full force and effect again.

- Amend the covenant so that the borrower will not be in continuing violation.

- Demand a cure of the violation within a certain period of time. The cure period is specified in the loan agreement between the borrower and the bank and generally runs from 10 to 30 days. Sometimes no cure period is permitted with respect to certain covenants.

- If compliance, waiver, or amendment has not cured the violation, or if no cure period is permitted, the bank may declare an event of default has occurred and demand payment of the loan.

If drafted properly, bank loan covenants should not interfere with a company's normal operations. Both the bank and the borrower come up with mutually agreeable covenants that each can live with for the length of the loan agreement.

LOAN COSTS

A variety of costs are associated with a bank loan. A brief review of some of the more routine fees is presented next.

Points

Up-front bank charges for a loan can be assessed for reviewing and preparing documents, performing credit checks, or simply agreeing to grant a loan. Points are one-time charges computed as a percentage of the total loan amount.

Compensating Balances

Some banks require a short-term borrower to establish and maintain a specified balance in an account at the institution as a condition of the loan. For example, the bank may require the borrower to keep at least 10% of the outstanding loan balance in an account. This “compensating balance,” often in a low-interest-bearing account, is a way the bank makes a loan more profitable. In effect, the bank is reducing the principal amount of the loan and increasing the effective rate of interest.

A compensating balance is negotiable, and some banks simply request an informal “depositor relationship” with the borrower. This relationship requires the borrower to use the bank for some other type of business, such as maintaining a credit card or opening some type of traditional savings account. Usually no set balances are required.

Unused Line Fees

An additional cost is the unused line fee, which is some percentage of the difference between a credit line's facility amount and the funded amount. Like other fees, this one is negotiated. Unused line fees typically range from .25% to 1% of the unused portion of the credit line.

Credit Boxes

This book uses the term “credit boxes” to describe access to most of the capital access points (CAPs) described in the following chapters. Credit boxes depict the access variables a borrower must exhibit to qualify for the loan. In other words, unless borrowers meet certain criteria, they will not be considered for the loan. In connection with the credit box, a summary of terms is offered representing the terms likely to be offered by the lender if the borrower's quantitative and qualitative characteristics fit within the credit box. Examples of these terms include interest rate, closing fees, monitoring fees, audit fees, and so on. By considering all of the terms of the deal, the expected rate of return is determined. As shown later in this chapter, these expected rates often are substantially greater than the stated interest rates.

Exhibit 17.7 depicts the credit box for a bank credit line as well as sample terms.3 These terms were taken from a Pepperdine survey, but it should be noted that terms fluctuate because of market conditions and changing motivations of the players.

EXHIBIT 17.7 Bank Credit Line Credit Box and Sample Terms

| Credit Box | |

| Earning Capacity | Collateral |

| Positive at funding | Initial funding of at least $1 million |

| Sufficient collateral base | |

| Financial Boundaries | Covenants |

| No more than 2.3 times debt/EBITDA | Fixed charge of at least 1.4 to 1 |

| Total liabilities to net worth of less than 3.5 to 1 | Total debt to tangible net worth of 1.5 |

| Sample Terms | |

| Example loan | $5 million facility; $3 million funded |

| 3-year commitment | |

| Interest rate | Prime rate + 4% (Prime = 3.5%) |

| Commitment fee | .5% of the facility amount |

| Closing fee | 1% of facility amount |

| Unused line fee | .3% per annum on unused portion |

The credit box is broken into four quadrants: earning capacity, collateral, financial boundaries, and covenants. A prospective borrower must meet each of the specified quadrant requirements to secure credit from the bank. An explanation of these terms is presented next.

Earning Capacity

The earning capacity of a company is the reported pretax profits of the borrower, adjusted for extraordinary items. Banks generally require a borrower to exhibit a positive earning capacity at the time of funding, with the expectation that earnings will continue during the life of the loan.

Collateral

Banks require a sufficient, stable collateral base. The preferred entry is at least $1 million in initial funding. Adequate assets secure most small loans. “Adequate,” in this case, means conservative advance rates are applied to the various pledged assets to determine loan size. A detailed discussion on eligibility of assets occurs in Chapter 20. Banks typically monitor the collateral at least quarterly.

Financial Boundaries

Banks require borrowers to meet several “boundary” ratios. These boundaries help define the overall riskiness of the lender's portfolio, which ultimately provides feedback to its credit box. One such boundary might state no deal is undertaken with a “Total Debt to EBITDA” ratio of more than 2.3 times. In this case, “total debt” means the total interest-bearing debt of the company. “EBITDA” means the earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization. This boundary is a technique for the bank to disqualify companies with excessive leverage. Another boundary is total liabilities to tangible net worth of not more than 3.5. “Tangible net worth” is defined as stockholders’ equity less book value of intangible assets, such as goodwill. Once again, the lender is setting up a financial fence to filter out overly risky transactions.

Covenants

Nearly all loans have financial covenants, which restrict the borrower in some way. These covenants vary greatly from one institution to another and must be negotiated with care. As an example, two covenants are offered in the credit box. The first covenant, fixed charge of at least 1.4 to 1, requires some definition. The fixed charge coverage ratio is defined as the ratio of:

- EBITDA minus capital expenditures not financed by the lender minus taxes to

- Current maturities of long-term debt plus interest expense.

This covenant shows whether current earnings on a cash basis are adequate to cover current fixed obligations on a cash basis. This covenant is tailored to meet the needs of the situation.

This credit box depiction illustrates some of the quantitative criteria needed to gain credit access to banks. Each lender is somewhat unique in its approach to making credit decisions. In other words, its credit box is engineered to meet its return on investment requirements. Of course, various qualitative aspects factor into the lending decision. Prospective borrowers should interview representatives of the institution about the characteristics of their credit box. Doing this saves everyone a lot of time and effort.

The sample terms show a possible deal offering for a credit line from a bank if a borrower successfully traverses the credit box. In this case, assume a $5 million facility is sought, with $3 million funded at closing. Typically, the facility begins with excess capacity, mainly so the credit has room to grow. Normally banks grant a credit line loan term of one to three years, with annual renewability at the option of the lender. The interest rate normally is computed and payable monthly and pegged to some known source, such as published in the Wall Street Journal. In the example, the interest rate is prime + 4%, with prime assumed at 3.5%. Thus the example uses 7.5% as the interest rate.

Most banks charge a closing fee at the time of funding. This fee, sometimes called a closing or origination fee, generally is expressed as an absolute number or a percent of the facility amount, not the funded amount. The commitment fee, which some banks charge for providing the loan, is .5% of the facility amount in this example. The closing fee in the example is $50,000 ($5 million facility amount times 1%). This fee, which is negotiable, varies from lender to lender. An additional cost is the unused line fee, which is some percentage of the difference between the facility amount and the funded amount. In the example, this fee is .3% per annum applied against $2 million ($5 million facility amount minus $3 million funded amount), or $6,000 annually, payable monthly. The next table shows a computation of the expected return to the bank from the sample terms.

| 1. | Total interest cost | $240,000 |

| ($3 million loan × 7.5% interest rate) | ||

| 2. | Commitment fee | |

| ($5 million facility amount × .5%) ÷ three years | 8,333 | |

| 3. | Closing fee | 16,666 |

| ($5 million facility amount × 1% ÷ three years) | ||

| 4. | Unused line fee | 6,000 |

| (($5 million facility amount – $3 million funded amount) × .3%) | ||

| Annual returns of loan | 271,000 | |

| Expected rate of return | 9.0% | |

| ($271,000/$3,000,000) |

The stated interest rate of 3.5% increases by the “terms cost” of 5.5%, which yields an expected rate of 9.0%. This assumes the closing fee is spread over the three-year life of the loan.

RISK RATINGS

Banks rate their borrowers through a risk rating system. Exhibit 17.8 shows a typical risk rating matrix. Although these systems vary by bank, many large banks use the 10-point scale shown in the exhibit.4

EXHIBIT 17.8 Borrower Grade Criteria (10-Point Scale)

Bank officers use the grading points to generate a borrower's risk rating. Companies are unlikely to exhibit characteristics uniformly at a single level across the grid. For instance, a company might be in a class 4 industry, with a class 5 position. Ultimately it is a judgment call by the lending officer as to the final risk rating assigned to a borrower.5 Risk ratings of 4 and lower tend to be large public companies. Many banks move a borrower into the special assets part of the bank once a risk rating hits 7. Most banks do not share current risk ratings with the customers. This practice makes it difficult for borrowers to know exactly where they stand with the bank.

It should be noted that most banks use risk ratings as well as other criteria to determine loan pricing. These criteria involve both qualitative issues, such as management strength and type of business (such as a niche versus commodity supplier of parts), as well as quantitative measures, such as return on capital requirements.

NEGOTIATING POINTS

There are a number of negotiable bank loan issues. Prospective borrowers should consider incorporating the next terms into the deal before closing a loan.

Interest Rate Pricing Matrix

Borrowers can negotiate an interest rate pricing matrix that lessens the interest rate over time as the borrower's financial condition improves. The matrix can tie to any of a variety of financial ratios. Typically only one ratio is chosen, and it corresponds to a problem in the borrower's position at the loan closing. For instance, if the prospective borrower is leveraged at the closing, the lender might give the borrower incentives to pay down debt by offering the next matrix.

| Pricing Matrix Based on Improving Leverage | ||

| Leverage | Prime Margin | LIBOR Margin |

| 3.0 or higher | 1.00% | 3.50% |

| 2.50 to 2.99 | 0.50% | 2.50% |

| 2.5 or lower | 0.00% | 2.00% |

For this example, leverage is defined as the ratio of total liabilities divided by tangible net worth. The lender might offer this pricing matrix if the borrower had a leverage ratio of more than three times at the closing, which would correspond to an interest rate of prime + 1% or LIBOR + 3.5%. The interest rate decreases as the leverage decreases, which normally is measured annually. Instituting a pricing matrix before the closing saves a borrower from renegotiating rates later. It may be possible to tie the pricing matrix into quarterly financial reporting.

Repayment Terms

Borrowers should negotiate repayment terms that match their ability to repay the loan. For instance, an interest-only period may be necessary before the principal is amortized. The key here is for the borrower to understand its cash flow well enough to tailor repayments to its ability to repay the loan.

Loan Covenants

Borrowers often overlook the opportunity for negotiating loan covenants. Most bankers are willing to tailor the covenants to a borrower's projections plus provide for breathing room. It is the borrower's responsibility to understand her financial ratios well enough into the future to negotiate these items.

Several covenants require special attention, such as:

- Limitations on shareholder compensation

- Limitations on acquisition of additional fixed assets

- Minimum or compensating cash balance

- Minimum equity level

Borrowers can have some covenants either limited or removed based on certain positive events occurring in the borrower's business. For instance, with proper negotiation, shareholder compensation can be increased once the borrower reaches a certain equity level.

Personal Guarantees

Typically, shareholders who own 20% or more of the borrower must personally guarantee the loan. In the heat of battle, most borrowers do not think to negotiate releases from the guarantee before the closing. Releases can be achieved through benchmarking the loan. For example, the guarantee could be either partially or fully released when the company reaches a certain profitability level or when the leverage of the company is reduced by a certain amount. Releasing, or “burning,” a personal guarantee, as it is sometimes called, is nearly impossible once a loan closes because there is no incentive for the lender to give on this issue.

Exhibit 17.9 shows the results of a recent Pepperdine Capital Market survey regarding bank personal guarantee requirements.6 Respondents were asked whether they would lend without personal guarantees to companies of various sales sizes. As might be expected, bankers tend to view personal guarantees as less important as company size increases.

EXHIBIT 17.9 Personal Guarantee Requirement

| Annual Sales Size | Yes | No |

| $.5 million | 16% | 84% |

| $1 million | 25% | 75% |

| $5 million | 30% | 70% |

| $10 million | 45% | 55% |

| $25 million | 52% | 48% |

| $50 million | 67% | 33% |

| $100 million | 65% | 35% |

Financial Statements

Many lenders require annual audited financial statements as a condition of closing the loan, especially for loans greater than $5 million. This is a negotiated item and a fairly important consideration when it comes to expense. Borrowers can agree to provide “reviewed” financial statements in many cases and save themselves more than $10,000 per year. Regardless of the level of outside accounting diligence, borrowers can expect to supply internally generated monthly financial statements to the bank each month.

Loan Closing Fees

The borrower pays the lender's cost of closing the loan. This fee includes legal, recording, appraisal, and other closing costs. If left unchecked, these fees can be substantial. For example, the closing fees for a $5 million funding can easily exceed $20,000. Borrowers can negotiate caps on these fees, such that the lender must receive permission from the borrower to exceed a certain amount. Sometimes the borrower can negotiate a fixed fee for the legal fees part of the closing. The borrower also incurs its own legal fees for reviewing loan documents, which are in addition to the lender costs.

The key to negotiating a deal with a bank is to consider all of the terms and conditions of the deal before executing a term sheet. Many borrowers focus on the interest rate to the exclusion of the other terms. As the examples show, there are many costs associated with these deals, and together they comprise the expected return.

TRIANGULATION

Capitalization is dependent on the value world in which the company is viewed and the availability of transfer methods. Banks view borrowers in the world of collateral value. Banks use this world to determine the value of the firm from a collateralized lending perspective. To these capital providers, margined collateral of a borrower is what matters most.

Access to capital affects the value of a firm. Banks provide a broad array of capital products and services that help companies grow. However, banks regulate capital access by imposing loan covenants and credit boxes that restrict a borrower's ability to access various types of capital.

In a recent meeting with an owner of a sporting goods manufacturer, the owner expressed his frustration with bank financing by saying “I can grow my business as fast as the bank will let me.” This owner would qualify for most capital access points on the Pepperdine Private Capital Market Line, but he chooses bank lending because of its low cost and infrequent intrusions. In addition, he does not want partners or to fund growth out of his own pocket. The owner figured he could grow his business by an additional 20% per year if the bank would fund it.

Bank lending is available to most transfer methods. Banks use covenants to protect their collateral position, which may prohibit a business transfer. Borrowers still prefer bank lending because often it represents the most effective capital source.

Many sellers do not disclose their business transfer plans to bankers because of the lower- and middle-market paranoia that only troubled businesses are for sale. Unfortunately, many owners believe bankers are more likely to withdraw or call their loans than they are to have empathy with the owner's desire to get out.

NOTES

1. Source: wsjprimerate.com.

2. This study is described by Robert T. Slee, “A Secret Your Banker May Not Be Telling You,” Business Journal (November 1996).

3. John K. Paglia, Pepperdine Private Capital Markets Project Survey Report, April 2010, bschool.pepperdine.edu/privatecapital.

4. Robert Morris Associates, A Credit Risk-Rating System (1994). Due to space limitations, the 10-point scale contains three columns not shown in the chapter. These columns are Financial Flexibility/Debt Capacity, Management and Controls, and Financial Reporting.

5. Ibid., p. 25.

6. John K. Paglia, Pepperdine Private Capital Markets Project Survey Report.