CHAPTER 23

Owners, Angels, and Venture Capitalists

Private capital markets begin with early-stage equity investing. These investors come in many shapes and sizes, including operating owner-managers, angels, and venture capitalists (VCs). Each of these groups plays a different role in the funding process, and each expects something different from the investment. This chapter describes how early-stage investors approach the problem.

People have been funding their own business start-ups since commercial activity began. Funding in the United States began to institutionalize in the 1930s and 1940s when wealthy families, such as the Rockefellers and Bessemers, began investing in private companies. Thus began venture capital. These original investors were far from “angels,” but they had money, connections, and know-how. Perhaps the first venture firm was J.H. Witney & Company, which was founded in 1946 and survives to the present day. General Georges Doriot, a teacher and innovator from Harvard, institutionalized venture capital. In the early 1950s, he had raised money for a dedicated fund and realized tremendous returns from investments in Digital Equipment Corporation and other early technology titans. Finally the U.S. government entered the early-stage investing picture, when in 1958 it launched Small Business Investment Companies via the Small Business Administration.

More modern angel investors tend to be wealthy investors who wish to participate in high-risk deals to satisfy some entrepreneurial urge and make a risk-adjusted return at the same time. The term “angel” was coined by Broadway insiders to describe the financial backers of Broadway shows. These angels invested as much to display their wealth as for the return on the investment.

Private equity comes in many forms. Exhibit 23.1 contains a schematic that describes various private equity investors.

EXHIBIT 23.1 Hierarchy of Private Equity Investment

Chapter 24 describes later-stage equity investment.

Five characteristics differentiate all private equity investing from other types of investing.

1. The private equity investor identifies, negotiates, and structures the transaction. Beyond the transaction, the private investor may be a manager, board member, or consultant.

2. The private equity investor has a finite holding period, normally five to seven years. Generally, it takes several years to position the company and at least one to two years to realize a maximizing exit.

3. Private investors seek high returns on their capital. The private investor seeks 25% to 40% returns or more, as opposed to 10% to 20% return expectations from public equity securities.

4. Private equity professionals invest in a company only when they are convinced the company's management team can execute the business plan. The conversion from initial idea to profit recognition is the wealth-creating activity, and managers who can conclude this conversion successfully tend to get funded.

5. Most private investors require some control over their investment. This control may involve contractually given rights rather than merely a majority stock position. For example, most private investors negotiate certain rights, such as antidilution, registration, tag-along, and so on. Taken together, these moves grant them a certain amount of control.

STAGES OF PRIVATE EQUITY INVESTOR INVOLVEMENT

There are five generally recognized stages of private equity investor involvement; the first three stages are generally considered the realm of early investors. This stage concept is important because it enables the equity market to match the appropriate funding source with the capital need, creating efficiency in the capital allocation process. The stages are:

Stage 1: Seed stage. This is the initial stage. The company has a concept or product under development.

Stage 2: Start-up stage. The company is now operational but is still developing a product or service. There are no revenues. The company has usually been in existence less than 18 months.

Stage 3: Early stage. The company has a product or service in testing or pilot production. In some cases, the product may be commercially available. The company may or may not be generating revenues and usually has been in business less than three years.

Stage 4: Expansion stage. The company's product or service is in production and is commercially available. The company demonstrates significant revenue growth but may or may not be showing a profit. The company usually has been in business more than three years.

Stage 5: Later stage. The company's product or service is widely available. The company is generating ongoing revenue and probably positive cash flow. The company is more than likely profitable and may have been in business for more than 10 years.

Various equity providers align with each of the five stages of capital needs. Personal and family or friends are the primary funding sources for seed or start-ups. Angel investors invest in early-stage companies that are in business with a product or service in production. VCs tend to favor Stage 3 and 4 companies. Those firms expect to achieve substantial revenue growth, but they have not yet shown a profit. Private equity groups, hedge funds, and family offices typically provide capital for Stage 5 companies.

Owner-Managers

For most companies, private capital is assembled initially by an owner-manager. These entrepreneurs are the backbone of the economy and have the most to gain or lose in the success or failure of their businesses. This group has limited resources to start-up a business. Small businesses use several sources available for start-up capital.

- Self-financing by the owner through cash, equity loan on his or her home, and or other assets

- Loans from friends or relatives

- Grants from private foundations

- Personal savings

- Private stock issue

- Forming partnerships

- Angel investors

- Banks

- Venture capital

- Private placements

Many small businesses are further financed through credit card debt. Although this debt is quite expensive, it may be the only capital available to the owner. Many owners seek a bank loan in the name of their business; however, banks usually insist on a personal guarantee by the business owner. Chapter 18 describes a number of government loan guarantee programs, all of which require personal guarantees from major shareholders.

Since private placements constitute a major source of capital for emerging companies, they will be further examined next.

PRIVATE PLACEMENTS

A private placement is a nonpublic offering of securities exempt from full Securities and Exchange Commission registration requirements. Placements usually are made directly by the issuing company stock, but they may also be made by an underwriter. The offering may be of debt or equity. Specific state and federal laws govern private placements. While placements occur that involve tens or hundreds of millions of dollars, this chapter primarily focuses on placement alternatives that enable a company to raise $5 million or less. Various chapters describe the various high-yield debt and equity capital providers, such as mezzanine, angels, and VCs. Prior to formally offering private securities to the market, companies should understand and follow the appropriate securities laws. Appendix F gives an overview of the laws and various types of private placements and discusses marketing strategies for a successful offering. Assuming that the promoter is in compliance with the securities laws, the next section suggests ways to market a private placement offering.

FINANCIAL BARN RAISINGS

Much like the physical barn raisings of the past, some of the most success placements occur within the community where the issuer resides. These financial barn raisings leverage relationships that transcend financial requirements. This technique works especially well in small communities, where other businesspeople are in position to assess the risk of the offeror's character and background. A financial barn raising is accomplished in these ways:

- Meet with the city fathers/mothers. This often involves the mayor and other businesspeople who know who has discretionary income and a pro-community outlook. The role of city fathers/mothers in the process is to make introductions to wealthy individuals.

- Orchestrate town meetings. Once a large list of potential investors is compiled, the next step is to organize a series of town meetings. These meetings usually are held at local country clubs, Rotaries, and other clubs that are suitable. These meetings are social gatherings; imagine a “wine and cheese” meets “soft sell” process.

- Close the deal. Soon after the four or five social gatherings, the company principals should personally meet with the top prospects. Most private placements fail in this step; the money does not just find its way to the company. It must be guided.

Many of these investors qualify as financing angels, which is covered later in this chapter. Financial barn raisings take place within a series of fairly complicated securities laws, so readers should engage a securities attorney before undertaking one.

WITHIN EXISTING BUSINESS RELATIONSHIPS

Quite often customers, vendors, and other business relationships comprise a potential group of investors. An issuer may be able to combine a private placement within the terms of a business relationship. For instance, when a new supply contract is negotiated, the issuer may be able to get a customer to invest in the issuer's security, especially when the money is needed to fulfill the contract.

WHY PRIVATE PLACEMENTS FAIL

Most private placements fail because either the offeror does not present the market with a security that promises enough return for the risk or the investors cannot ascertain the risk of the investment. Most of these offerors are very small companies, with business models that are unproven. With this as a backdrop, it is reasonable for investors to expect at least 25% to 35% effective returns on their investments. Individual investors typically are not in a position to measure the risk of most private placements. Protecting individual investors from themselves explains why the blue-sky laws exist to begin with. Offerors can be successful with their placements if they:

- Provide the necessary information. Investors need basic information before they will consider investing.

- Does the product or service solve a problem or need?

- How many competitors are already in the marketplace?

- Who are potential customers, and how will they be reached?

- Is the management capable of delivering the business plan?

- What does the investor get for her investment?

It is the entrepreneur's responsibility to supply this information in a clear and concise fashion. - Are honest about the risk/return proposition. It is the offeror's responsibility to offer potential investors a reasonable return for the risk. This may mean postponing an offering until the business is stable enough to merit outside investment.

- Treat all investors at arm's length. Even if the offering is targeted at family and friends, the offeror should treat the entire process as if all of the investors are outsiders. There should be no special deal to the offerees because they are family.

- Beware of costly professionals. Many brokers and lawyers are willing to take an offeror's money for doing the up-front work. Some of this expense is necessary, but prospective offerors should be wary and ask questions about experience and successful past offerings. As with any professional services purchase, potential offerors should talk with past clients before engaging the professional.

- Market … market … market. Offerors should access the market in every way possible. This means employing the marketing techniques just mentioned simultaneously. Throwing numerous financial barn raisings with an active board is a good way to access the market. Networking is the key to success.

It is extremely difficult to raise money through private placement. Prospective offerors who view this entire process as hand-to-hand financial combat will not be disappointed. At the end of the day, the hidden hand of capitalism helps determine winners from losers.

But for certain owners, finding an angel is the best way to go.

Angel Investors

Angels typically invest their own funds, unlike VCs, who manage the pooled money of others in a professionally-managed fund. The Center for Venture Research at the University of New Hampshire (www.wsbe.unh.edu/cvr), which does research on angel investments, has developed the next profile of angel investors.

- The “average” private investor is 47 years old with an annual income of $90,000, a net worth of $750,000, is college educated, has been self-employed, and invests $37,000 per venture.

- Most angels invest close to home and rarely put in more than a few hundred thousand dollars.

- Informal investment appears to be the largest source of external equity capital for small businesses. Nine out of ten investments are devoted to small, mostly start-up firms with fewer than 20 employees.

- Nine out of ten investors provide personal loans or loan guarantees to the firms they invest in. On average, this increases the available capital by 57%.

- Informal investors are older, have higher incomes, and are better educated than the average citizen, yet they are not often millionaires. They are a diverse group, displaying a wide range of personal characteristics and investment behavior.

- Seven out of ten investments are made within 50 miles of the investor's home or office.

- Investors expect an average 26% annual return at the time they invest, and they believe that about one-third of their investments are likely to result in a substantial capital loss.

- Investors accept an average of three deals for every ten considered. The most common reasons given for rejecting a deal are insufficient growth potential, overpriced equity, lack of sufficient talent of the management, or lack of information about the entrepreneur or key personnel.

- There appears to be no shortage of informal capital funds. Investors included in the study would have invested almost 35% more than they did if acceptable opportunities had been available.

For the business seeking funding, the right angel investor can be the perfect first step in formal funding. It usually takes less time to meet with an angel and to receive funds, due diligence is less involved, and angels usually expect a lower rate of return than a VC. The downside is finding the right balance of expert help without the angel totally taking charge of the business. Structuring the relationship carefully is an important step in the process.

There are at least five types of angel investors.1

1. Business owners

2. Key executives

3. Self-employed professionals

4. Sales and marketing professionals

5. All others

Business owners tend to make the best angels for the emerging business. They understand the problems better than others and often mentor the founder. Key executives offer a different set of solutions from the business-owner angel, but they are nearly as valuable and important. Executives bring the professional management techniques needed by many early-stage companies. Self-employed professionals, such as doctors, dentists, lawyers, and the like, may be more benign for the entrepreneur because they are not as likely to call the loan or demand their money back. But they may have less to contribute to the venture in the form of helpful advice, information, and contacts. They care about the founder and what he or she is trying to achieve; however, they may not focus as much on the return on their investment as VCs would. Sales and marketing professionals may fill a major gap in the entrepreneur's skill set. All business begins with a sale, and small businesses are even more dependent on this expertise.

Successful entrepreneurs also can be angels. They can be an entrepreneur's best bet because their business advice and contacts may make the difference between success and failure. However, they can become meddlesome, or their advice may not be worth much if the business they run is very different from the entrepreneur's business.

Exhibit 23.2 provides capital coordinates for angel investors.

EXHIBIT 23.2 Capital Coordinates: Angel Investors

| Capital Access Point | Angels |

| Definition | Angel investors tend to be wealthy investors who wish to participate in high-risk deals to satisfy some entrepreneurial urge and make a risk-adjusted return. |

| Expected rate of return | Seed: 60%; start-up: 45%; early: 35% |

| Authority | Angels come in five basic types: business owners, key executives, self-employed professionals, sales and marketing professionals, and all others. |

| Value world(s) | Early equity |

| Transfer method(s) | Negotiated, possibly via a private placement |

| Appropriate to use when . . . | Angels are start-up or early investors. They bet more on the entrepreneur and less on the product and market opportunity. |

| Key points to consider | Angel financing may take the form of a promissory note or preferred or common stock. Most angels are likely to remain passive, except for a board position. Founders should choose the type of angel that provides the greatest assistance to the company in meeting its goals. |

Many major cities have bands of angels, or organized groups of early-stage investors. These groups generally invest from $100,000 to $2 million per deal. Angels tend to rely more on intuition than analytical investment techniques. They bet more on the entrepreneur and less on the product and market opportunity. Angels often host Internet sites but are also found through lawyers and accountants who specialize in new venture legal or accounting work. Angels are particularly helpful to entrepreneurs on a personal level, since many band members are professionals with similar backgrounds as the investee. Some angels are themselves VCs with their own firms, which invest as angels for early access to good deals.2

Exhibit 23.3 shows the credit box that describes the characteristics necessary to obtain angel financing.

EXHIBIT 23.3 Angel Financing Credit Box

| Credit Box |

To qualify for angel financing, an applicant must:

|

Obtaining angel financing relies on leveraging personal contacts. More than the other types of institutional private equity, angel financing money is raised for more than purely economic reasons. Some angels may invest because of paternal instinct or just for the thrill of playing the game. But financial returns are important. Since this group enters a deal early, they require a high return. Exhibit 23.4 shows expected return and other data from a survey of angels.3

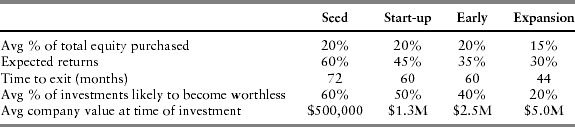

EXHIBIT 23.4 Angel Terms by Stage of Investment

Angels are minority investors with a five- to six-year investment horizon. Expected returns range from 60% for Seed investments to 30% for the expansion stage. A large percentage of early-stage investments are expected to become worthless.

Exhibit 23.5 shows an example term sheet. Angel terms usually are structured in one of three ways:4

EXHIBIT 23.5 Example Angel Term Sheet

| This term sheet is being offered to the Company and will remain in effect until day of XX, 20XX. |

| Offer of Investment |

| The Fund will purchase, together with any syndicated investors, (collectively the “Investors”), common shares (the “Shares”) at a price of $* per Share. The total round for all Investors will be $* of which the Fund will invest $* to acquire a total of * Shares. So long as the Investors hold their Shares and until a liquidity event, they shall have the right to exchange them for the same kind and class of securities issued by the Company (the “New Securities”) in any follow on financings should such New Securities have rights superior to the Shares. The Investment will be made pursuant to an Investment Agreement made between the Investors, the Company and certain of its principals (the “Principals”). The capital structure on closing will be as described in the attached Share Register. |

| Board of Directors |

| The Fund believes that early-stage investments need strong mentoring and governance provided by a high-quality, engaged Board. On the completion of the investment, the Board will be comprised as follows: |

|

| Share and Option Vesting |

| The Fund believes that it is important that the Principals' interests align with the Investors. In this regard the parties agree that all stock options and all nominally priced previously issued shares will vest on the following basis: |

|

| All share and option vesting will accelerate on a sale of the Company. An Escrow Agreement will be entered into to provide for the vesting. |

| Liquidity Event |

| To ensure that a return can be provided to all of the Company's shareholders when an opportunity presents itself to sell the Company, the Fund will require a “drag-along” right be added to the Company's constating documents to allow the holders of 51% of the issued shares of the Company to cause the sale of all of the shares of the Company. |

| Reporting to Shareholders |

| The company will send a CEO Update monthly to all shareholders. Financial statements are also available upon request. |

| Investor Rights |

| Investors have the right of first refusal to participate in future financings. Any changes to the capital structure, new shares, options, or debt requires the approval of the majority of the investors in this round. |

| General |

| The Company will pay the legal costs of the Fund not to exceed $6,500, plus taxes and disbursements thereon. The Company will keep confidential this Term Sheet and all discussions with the Fund for a period of two years. |

| Binding Nature |

| This Term Sheet will terminate on *[date], unless terminated earlier by the Fund. The Company will not seek alternate financing unless and until this Term Sheet has terminated or been terminated by the Fund. The confidentiality provisions will survive termination of this Term Sheet. Acknowledged and agreed to by the Company and by the Fund this XX day of X, 20XX by: [Signatures] |

1. They initially take a promissory note, with deferred monthly or quarterly interest payments for the first year or two. The note may be convertible into options that are exercisable at various performance benchmarks, such as when sales or profits reach a certain level. Ultimately, the options may be worth 15% to 30% of the equity, depending on the deal. Angels typically begin as passive creditors during the formative launch phase but want to see detailed financial statements at least quarterly beyond the first year. They also require at least one seat on the board of directors and will actively oversee the entrepreneur's implementation of the business plan.

2. Angels initially may take a cumulative convertible preferred stock position. They allow the firm to defer fixed-cash dividends for at least a year or two. Once again, they seek a role on the board and help implement the business plan.

3. They take a common voting equity position up front, have their place on the board, and may be actively involved in company management. They may want to add to the management team or, at the least, hire consultants to help work on key projects. Depending on the entrepreneur's perspective, this approach may be the best or worst of the three formats. It can be the best situation for entrepreneurs who need hands-on help and connection to the broader business community. It is less than ideal for entrepreneurs who want their own team of managers in place.

Overall, the deal hinges on the quality of the relationship between the angel and the entrepreneur. Angel financing is best suited for early-stage opportunities where the owner-manager needs capital plus guidance from experienced businesspeople. Owners of middle-market companies are not normally searching for angel investors. However, they may choose this financing route for a new product or business that is spun off from the existing company, thereby diversifying risk.

EXHIBIT 23.6 Venture Capital Investment Filter

Exhibit 23.5 shows an example term sheet.5

Venture Capital

Venture capital is money provided by professionals who invest alongside management in early- to expansion-stage companies that have the potential to develop into value-creating enterprises. Venture capital is an important source of equity for early companies and less important for established middle-market companies.

Venture capital firms are pools of capital typically organized as limited partnerships. The VC may look at several hundred investment prospects before investing in only a few companies. VCs help grow companies using skill sets obtained from other similar ventures. The most successful VCs tend to be entrepreneurs first and financiers second.

VCs generally:

- Finance new and rapidly growing companies.

- Purchase equity securities.

- Assist in the development of new products or services.

- Add value to the company through active participation.

- Take higher risks with the expectation of higher rewards.

- Have a long-term orientation.

When considering an investment, VCs carefully screen the technical and business merits of the proposed company. Venture capitalists employ a strict filtering process, depicted in Exhibit 23.6.6

VCs mitigate the risk of venture investing by developing a portfolio of young companies in a single venture fund. They often coinvest with other professional venture capital firms, called syndicating a deal. In addition, many venture partnerships manage multiple funds simultaneously. Exhibit 23.7 provides the capital coordinates for venture capital.

EXHIBIT 23.7 Capital Coordinates: Venture Capital

| Capital Access Point | Venture Capital |

| Definition | Venture capital is money provided by professionals who invest alongside management in early- to expansion-stage companies with potential to develop into significant economic contributors. |

| Expected rate of return | Seed/Start-up: 40%; early: 36%; expansion: 30%; later: 25% |

| Authority | Institutional venture capitalists |

| Value world(s) | Early equity value |

| Transfer method(s) | Venture capitalists create their own transfer by valuing in the world of early equity, then capitalizing the valuation for shares of the investee. |

| Appropriate to use when . . . | An entrepreneur needs capital and strategic management support to meet a business plan's objectives. |

| Key points to consider | Venture capitalists help companies grow, but they eventually seek to exit the investment, usually in three to seven years. Venture capitalists can be generalists, investing in various industry sectors, various geographic locations, or various stages of a company's life. Or they may be specialists in one or two industry sectors. |

Venture Capital Credit Box

Accessing venture capital is a long shot. The investment filter shown in Exhibit 23.6 puts the odds of receiving venture capital funding at less than 1%. Such a small chance of success means understanding the investment characteristics of the venture credit box, shown in Exhibit 23.8, is especially important for prospective investees.7

EXHIBIT 23.8 Venture Capital Credit Box

| Credit Box |

To qualify for venture capital, an applicant must:

|

The keys to attracting venture capital are management experience, the presence of a scalable business model, and the promise of at least a 35% compounded return on the investment. VCs are drawn to management teams that have previously achieved like-kind results. Scalable business models are essential. Scalability means that the company can grow benefit streams at an increasing rate as revenues grow. The minimum 35% compounded rate of return expectation is extremely difficult to achieve. To put this in perspective, assume a VC invests $5 million in PrivateCo with a five-year exit strategy. If the VC is successful in meeting its return expectation, its position in PrivateCo will be worth more than $22 million at the time of exit. How many companies can increase their value by this much in a five-year period? It is little wonder that the venture filter is so stringent.

Exhibit 23.9 shows surveyed results by stage of investment.8

EXHIBIT 23.9 Venture Capital Terms by Stage of Investment

VCs are minority investors in private companies, but they acquire more of a company on the average than do angels. Similar to angels, VCs expect to be invested for five years or so. But VCs are much more confident than angels regarding the percentage of investments that will become worthless, possibly because VC investments are made to more valuable companies.

Structure of the Venture Deal

Investments by venture funds into companies are called disbursements. A company receives capital in one or more rounds of financing. The venture firm provides capital and management expertise and usually takes a seat on the board to ensure that the investment has the best chance of success. The VC calls an investee a portfolio company. Typically, portfolio companies receive several rounds of venture financing in their life. Later-round investments are linked to the investee's ability to meet negotiated benchmarks. This incremental investing process enables a venture firm to reserve some capital for later investment in some of its successful companies with additional capital needs.

The following example gives an inside look at various venture capital issues.

Example

PrivateCo has developed a special technology it believes will revolutionize a segment of its industry. Joe Mainstreet creates a new company, NewCo, which contains the associated patents and specialized equipment. His goal is to raise $10 million to fund the business plan. A local venture capital company, VentureCo, agrees to invest $10 million in the form of convertible preferred stock. But VentureCo believes the opportunity is riskier than its normal investment profile and is asking for an added return. In addition to the typical preferred features, VentureCo wants participating preferred stock.

PrivateCo's investment banker, Dan Dealmaker, explains that participating preferred is a form of convertible preferred stock that provides the holder with extraordinary rights in the event NewCo is sold or liquidated. If VentureCo receives back its purchase price for the stock and possibly some guaranteed return on that purchase price, it then receives an additional pro rata share of the remaining sale or liquidation proceeds from NewCo.

Dealmaker uses the next example to illustrate how a “participating” feature in a convertible preferred stock affects the return on investment for both VentureCo and NewCo. The example assumes VentureCo purchases 2 million shares of convertible preferred stock for $10 million and NewCo owns 8 million shares of common stock. The illustration shows the return to VentureCo and NewCo if the company later sells for $20 million.

| Preferred Stock Comparison | ||

| Nonparticipating | Participating | |

| Preferred purchase price | $10 million | $10 million |

| Number of shares | 2 million | 2 million |

| Other shares—common | 8 million | 8 million |

| Sale price distribution on a $20 million sale | ||

| Preferred | $4 million | $12 million |

| Common | $16 million | $8 million |

The participating preference is meaningful. In the case of a $20 million sale, the preferred holder gets $12 million, as opposed to $8 million for the common stockholders. This is considerably richer than the $4 million that would be distributed to a nonparticipating preferred holder.

Dealmaker recommends that NewCo negotiate a sunset provision into the preference that makes it inoperative after a passage of time or in a sale or liquidation that would generate an agreed-on minimum return without the preference.

Venture capital investing involves both art and science, as the following lessons suggest.

Lessons from a Successful Venture Capitalist

- Manage the “three risks.” Technology risk, market risk, and financing risk all can threaten the success of a potentially lucrative scientific discovery.

- Invest with a teaspoon. When putting first money into a new discovery, start with small amounts.

- Remember your tape. A person's life and the life of an enterprise are the sum total of actions and decisions over a period of time—a tape that never stops rolling, according to Georges Doriot.

- Control the technology. Take an ownership interest, not a license, in new technology in order to ensure it is maximized in commercial application.

- Avoid potholes. Associate only with quality people. Avoid unproductive, intramural bickering. Let science lead the way.

Source: Robert Finkel and David Greising, The Masters of Private Equity and Venture Capital (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2009), p. 219.

PRE- AND POSTMONEY VALUATION

Private equity investors tend to talk about premoney and postmoney valuation. When a private investor invests money in a company, it establishes the company's postmoney valuation. A postmoney valuation equals the premoney valuation of the company plus the amount of the investment. This difference in terminology seems harmless, but it can cause serious misunderstandings. Consider these formulas:

By way of example, suppose Joe and Jane Mainstreet own 1,000 shares of PrivateCo, which is 100% of the equity. If an investor makes a $2 million investment into PrivateCo in return for 200 newly issued shares, the implied postmoney valuation is:

To calculate the premoney valuation, the amount of the investment is subtracted from the postmoney valuation. In this case, it is:

The initial shareholders dilute their ownership to 10/12 = 83.33%.

NEGOTIATING POINTS

Investees should not begin to negotiate a term sheet with private equity investors until they understand the offered terms. This is also a good time to get legal and other professional advice. The entire deal should be comprehended before specific clauses or provisions are discussed. Once the deal is understood, investees can expect to negotiate the next points.

Process of Developing the Valuation

Different investors value an interest quite differently, depending on their understanding of the risk of the investment. Investees should not negotiate a value or price offered for their shares until they understand the process used by the prospective investor. Even after the process is well understood, the valuation process should be negotiated rather than the final value.

For example, suppose an equity investor offers to invest $10 million in a series B convertible preferred round and values the company at $75 million. The investee believes the enterprise value is closer to $100 million. The investor has valued the company using net present value analysis. The investor has employed a higher discount rate and lower cash flows than the investee thinks reasonable. One possible solution is to make the investment less risky for the investor. This might be accomplished by creating a revenue benchmark or milestone, causing the investor to tranche the investment over a period of time. The ultimate dilution might split the difference between the investee and investor valuations.

Managing Multiple Offers

It is difficult to run auctions or other methods of generating multiple offers from equity investors. Part of the problem is that institutional investors talk to each other and often syndicate their deals. Another constraint is the time required by the investee to initiate and manage multiple offers. Managing multiple offers is more likely to be successful if the investee has engaged a representative. Even with professional assistance, it probably is wise to deal with investors who are widely separate geographically.

Board and Governance Issues

When investors have legal control, the board is mainly ceremonial. Minority equity investors often want the right to appoint a designated number of directors to a company's board. This enables investors to better monitor their investment and have a say in running the business. Companies often resist giving equity investors control of, or a blocking position on, a company's board. A frequent compromise is to allow outside directors, acceptable to the company and investors, to hold the balance of power. Occasionally, board visitation rights, in lieu of a board seat, are granted.

A variety of governance issues should be described in the term sheet. In this context, the term “governance” means how the major financial and legal issues of the company will be managed. In many cases, these issues are broken into majority and supermajority terms, as shown next.

- Corporate Governance. The PrivateCo board will have five members: three will be appointed by the series A common holders and two by the series B common holders. The series A holders will appoint the chairman and chief financial officer of the company. These decisions will require a supermajority approval of the board (at least four board votes):

- Elections of directors

- Issuance of new interests

- Sale of entire business

- Changes to share rights

- Distributions or dividends, except for normal tax distributions

- Incurring debts of more than $1 million

- Acquisition of another business

- Dissolution of the company

- Key employee hires

- Major changes in the employee benefits

- Optional buyouts

- Changes to the employment contracts, noncompete agreements, operating agreement, shareholder agreement, and buy/sell agreement

- Job termination of a shareholder

These decisions will require a majority (at least three board votes): - Expenditures on capital items in excess of $75,000 per item

- Minor changes in the employee benefits package

Management should negotiate all of the major actions it can undertake without any board interaction.

Vesting of the Founders’ Stock

Equity investors often insist that all or a portion of the stock owned or to be owned by the founders and key employees vest only in stages after continued employment with the company. This condition is often called an earn-in of stock. This is an especially contentious issue for early-stage companies because the value of the company is so uncertain. Vesting of founder stock is less of an issue in later-stage companies. If forced to earn-in over time, managers should negotiate benchmarks that are within their control to achieve without further actions by the equity investor.

Additional Management Members

Additional key managers sometimes are required as part of the equity investment. This is a highly negotiated item, because neither the current management team nor the equity investor wants to dilute their position. Perhaps the best compromise is to employ a deferred compensation plan, such as phantom stock, for the new players. After a period of several years, the added managers may participate in stock option plans that include all of the managers.

Employment Agreements with Key Founders

Management should negotiate employment agreements as part of the funding. Key issues often are compensation and benefits, duties of the employee and under what circumstances those duties can be changed, the circumstances under which the employee can be fired, severance payments on termination, the rights of the company to repurchase stock of the terminated employee and at what price, term of employment, and restrictions on postemployment activities and competition.

Special care should be taken to tie the employment agreement to the buy/sell agreement. For instance, if a manager is terminated without cause, that manager's stock should be repurchased at full value. However, if the manager is terminated with cause, the shares probably will be repurchased at a discount to full value. Managers also should negotiate to have the company pay for life and disability insurance that will fund the employment agreement and buy/sell.

Investor Transfer Rights

A number of investor transfer rights are negotiated. Some of these are:

- Preemptive rights. The right of the investor to acquire new securities issued by the company to the extent necessary to maintain its percentage interest on an as-converted basis.

- Registration rights. Investors typically receive certain registration rights for public offerings. Negotiations center around whether the investor receives piggyback and/or demand registration rights, and who pays the expenses of each such registration. Piggyback rights allow investors to have their securities included in a company-initiated registration. Demand rights mean that holders can require the company to prepare, file, and maintain a registration statement. Normally, investors require the company to pay all of the holder's expenses regarding registrations.

- Right of first refusal. Right of the investor to be first offered securities to be sold by other shareholders and/or the company.

- Right of cosale. Right of the investor to sell its securities along with any securities sold by the company or the other shareholders.

- Tag-along or drag-along right. Right to obligate other shareholders to sell their securities along with securities sold by the investor.

These rights should be set forth in the term sheet and generally terminate upon an initial public offering of common stock by the company.

Antidilution Provisions

Investors require protection against dilution from future additional investment in the company. Antidilution provisions entitle an investor to obtain additional equity in a company without additional cost when a later investor purchases equity at a lower cost per share. These provisions come in two primary forms: ratchets and weighted average.

Ratchets give investors additional shares of stock for free if the company later sells shares at a lower price. For example, if an investor who has a ratchet purchases 100,000 shares of company stock for $200,000, or $2 a share, and the company later sells another investor 100,000 shares for $1 each, the first investor would receive another 100,000 shares for free. The result would be the same if the second investor bought only one share for $1.

The weighted average method uses a formula to determine the dilutive effect of a later sale of cheaper securities and grants the investor enough extra shares for free to offset that dilutive effect. Assume that an investor buys 600,000 shares of company stock for $4 per share when management owns 1,400,000 shares. A later investor buys 400,000 shares from the company for $2 per share. A ratchet would give the first investor 600,000 new shares for free to reduce the average price per share to $2.

The weighted average antidilution method is usually more favorable to management shareholders than the ratchet method. Under the ratchet method, the protected investor is entitled to get enough free shares to reduce his or her price per share to the same price paid by the later investor regardless of the number of shares sold to the later investor.

TRIANGULATION

Private equity investors provide various types of capital to growing companies. The various equity providers align with the five stages of capital needs. Owners, angels, and venture capitalists typically invest in start-up, early, and expansion-stage companies, respectively. Many companies evolve from one capital provider to the next as their capital needs change.

Companies in need of early-stage equity are viewed in the world of early equity or the world of market value, depending on the stage of investment. As the name suggests, early-stage companies are valued by angels and venture capitalists in the world of early equity, whereas private equity groups—the subjects of the next chapter—use market value to determine deal parameters. Value world collisions are the norm when private equity is sought. Founders and other shareholders tend to view value from the owner value world perspective, which often results in an overvaluation, at least from the perspective of the particular private equity provider. Many deals fail because this collision cannot be reconciled.

From the moment a company receives private equity, it is in play to be transferred. Private equity providers are driven to invest by the probability of successful exits. They negotiate deals that increase the odds of a profitable transfer. As a last resort, the provider will transfer its shares back to the company at some future date. The more profitable exit for the investor, however, usually involves a public offering or sale to a synergistic acquirer. This can be another source of friction between shareholders and investors: Shareholders may wish to grow and hold while investors want to grow and harvest. Both parties need to understand the other's motivations and plan accordingly.

NOTES

1. Mark Long, Raising Capital (San Diego: Promotions Publishing, 1998), pp. 129–130.

2. A good online tool for angel financing is: www.vfinance.com.

3. John K. Paglia, Pepperdine Private Capital Markets Project Survey Report, April 2010, bschool.pepperdine.edu/privatecapital.

4. David Newton, “An Explanation of Angel Investors,” Entrepreneur (July 2000).

5. www.angelblog.net/The_One_Page_Term_Sheet.html

6. Dante Fichera, The Insider's Guide to Venture Capital (Roseville, CA Prima Venture, 2002), p. 292.

7. John K. Paglia, Pepperdine Private Capital Markets Project Survey Report.

8. Ibid.