CHAPTER 26

Business Transfer: Introduction

Business transfer includes a spectrum of possibilities, from transferring the assets of a company to transferring partial or enterprise stock interests. Private business transfers take place in private capital markets. Because private markets are less visible than public markets, many observers do not recognize a structure in private markets. Yet a structure exists.

This chapter delineates the unique motives of public managers and private owners as well as the means to convert motives into action. The chapter also introduces the private business ownership transfer spectrum, which demonstrates the range of transfer alternatives available to private owners.

PUBLIC MANAGER AND OWNER MOTIVES

Motives that drive a public manager and private owner to transfer a business interest are unique to each party. Exhibit 26.1 compares public and private transfer motives. Understanding individual motives helps explain the behavior of the players.

The perspective of the players is the biggest difference between transfer motives of public manages and private owners. Public managers have an entity or corporate perspective, whereas private owners have personal transfer motives. Most private owners sell out because they are burned out. Public companies do not get tired. Private owners cannot easily replace themselves because they are so control-oriented. They also tend to wear so many hats that no one person can replace them. Public companies are organized functionally, so any one executive can be replaced without forcing the need to sell the business. Public companies are designed to last forever. Private companies usually do not outlast the founding owner.

Public entity motives are different from personal owner motives relative to diversification, legacy building, and likely retirement vehicles. Most public managers seek to diversify their businesses because diversification lessens ownership risk, thus increasing job security. As a result, public managers are more likely to diversify their businesses into unfamiliar territory. In contrast, private owners usually wish to diversify their estates, the majority of which is vested in the value of the businesses. Therefore, private owners are more likely to employ sophisticated estate planning techniques. For example, many private owners want to transfer the business to their children as a family legacy. There is no corresponding motive on the public side. Further, private owners typically forgo some compensation, especially in the early years, in order to reinvest earnings in the business; they are anticipating a major capital event. Public managers, however, look to maximize ordinary income and use 401(k)-type plans to build their retirement nest egg.

EXHIBIT 26.1 Comparison of Transfer Motives

| Public Managers Want to | Private Owners Want to |

| Meet entity transfer motives | Meet personal transfer motives |

| Diversify the business | Diversify their estate |

| Create a business legacy | Create a family legacy |

| Use 401(k) as main retirement vehicle | Use transfer of business as main vehicle |

| Have many shareholders | Have no partners |

Finally, public managers operate in a market that trades small minority interests on a daily basis. A stated goal of most public managers is to increase the number of shareholders in their company. This creates a more fluid market for the stock while giving managers more control over the company since the ownership is spread out. Private owners, in contrast, are not motivated to sell small parts of their business. Private markets provide little support for this activity, and private owners typically do not want partners.

Motives alone do not create a successful transfer. The ability to convert motives into action is required. In other words, a participant needs the means to realize a motive in a market.

Means of Transfer

Having the means of transfer implies having the available tools to implement a transfer strategy. Certainly public managers have the means to transfer their businesses. Market makers ensure a liquid trading market. Every public company is only one vote by the board of directors away from selling out. There are scores of public investment bankers ready, willing, and able to assist in the transfer. The transparency of a public company's financial information enables the market to react quickly to a sale. Investment bankers are able to run highly public transfer processes, which add to the likelihood for a successful transfer.

Although the means of transfer is less fluid for private companies, the tools are available to the private owner to achieve the desired transfer result. Without a ready market, a private owner is much more involved in transfer planning and transfer implementation than a public manager. Several groups of transfer players assist the private owner. At the low end of the transaction curve, say, below $2 million, business brokers provide valuation and enterprise transaction support. For medium-size transactions, mergers and acquisitions (M&A) intermediaries represent sellers and buyers and assist in limited capital-raising activities. For larger transactions, such as those above $10 million, private investment bankers arrange capital structures and provide the spectrum of valuation and transfer services.

A combination of factors has enabled financial engineering to impact the private capital markets. Financial engineering is the use of sophisticated financial methods to provide solutions to complex problems. Many transfer players employ financial engineering to provide a means of transfer to private owners. Estate planners engineer multivariable solutions to help owners minimize estate and other taxes. Many of the internal methods described herein are used for this purpose. Private investment bankers use financial engineering to service clients with diverse needs. For example, engineering a successful recapitalization requires an understanding of transfer processes as well as a command of market valuation and negotiation with private equity groups. Since most middle-market businesses are entangled with their owners’ lives, their transfer techniques reflect that. The triangulation of valuation, capitalization, and business transfer proposed in this book enables owners to enjoy more sophisticated means of transfer services.

Business owners have a host of transfer alternatives from which to choose. The alternatives are organized as transfer channels and methods.

PRIVATE BUSINESS OWNERSHIP TRANSFER SPECTRUM

Most owners of private businesses think they have only a few transfer choices. Some intermediaries, and other industry professionals, enforce this limitation because they work in a narrow, specialized area and do not know the full range of options available. Owners and their teams may be advised that selling the entire business is the best solution when, in fact, this might be the least desirable alternative.

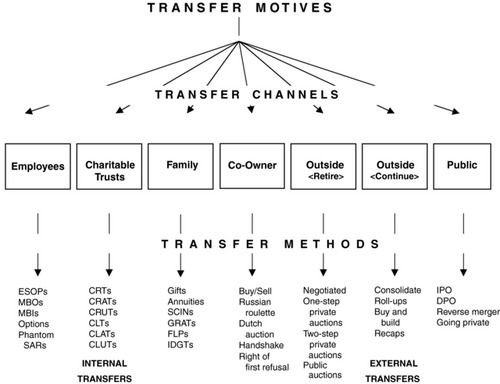

Exhibit 26.2 depicts the business ownership transfer spectrum. The macro private transfer options, called transfer channels, attract a cluster of specific alternatives, called transfer methods. Transfer methods—the actual techniques used to transfer a business interest—are grouped under transfer channels. Transfer channels and transfer methods provide a construct by which the range of business transfer options can be explained. Owners select transfer channels with the optimum potential, based on their motives for selling.

EXHIBIT 26.2 Business Ownership Transfer Spectrum

Transfer methods follow a specific set of steps, in a particular order, to achieve a goal. These methods are instruments, or sets of instruments, for accomplishing the objective of transferring a business. The criteria for developing a sound methodology are similar to those found in the world's argument. They include:

- What authority or logical structure holds the method together?

- What standards are prescribed or proscribed?

- What language is used in the method?

- How does choosing a method also determine the results?

- To what extent can the method be combined with other methods?

There is an authority that governs transfer methods and a language and logic that provides structure. The methods may be tax-driven, market-driven, or finance-driven, or a combination of all three. It is frequently possible to combine methods without violating the internal integrity of each, because transfer methods are not necessarily mutually exclusive.

Private business transfer exists within a discrete, niche market that often plays out in an ad hoc fashion. In other words, a menu of transfer alternatives is available for use by an owner. Motives of owners drive this market. Motives range from creating a family legacy to changing the landscape of an industry. A host of transfer players assist owners to meet their goals. The private markets largely provide owners with all of the means of transfer they need to convert motives into action. This rich range of alternatives, and the means to achieve those alternatives, has developed significantly in the past 10 to 15 years.

An owner has seven transfer channels from which to choose. They are:

1. Employees

2. Charitable trusts

3. Family

4. Co-owner

5. Outside, retire

6. Outside, continue

7. Public

The choice of channel is manifested by the owner's motives and goals. For instance, owners wishing ultimately to transfer the business to their children choose the family transfer channel. Owners who desire to go public choose the public transfer channel, and so on.

Each transfer channel contains numerous transfer methods. A transfer method is the actual technique used to transfer a business interest. For example, grantor-retained annuity trusts, family limited partnerships, and recapitalizations are methods by which an interest is transferred. Some methods are aligned exclusively with certain channels, such as an employee stock ownership plan (ESOP) within the employee channel. Other methods can be applied across channels, such as the use of a private annuity with either the family or outside channels.

When a business interest transfers within the company, it is called an internal transfer. These are custom-tailored solutions designed to transfer all or part of the business internally, without the uncertainty of finding an outside buyer for the business. Examples of internal transfer methods include management buyouts, charitable remainder trusts, family limited partnerships, and a variety of other estate planning techniques.

External transfers involve transferring business interests to a party outside the company. External transfers employ a process to achieve a successful conclusion. Examples of external transfers include negotiated sales, roll-ups, and reverse mergers. As an illustration, if an owner of a medium-size company wants to sell her business for the highest possible market price, she might employ a private auction process, which should produce the highest possible offers available in the market at that time.

The next chapters describe the business ownership transfer spectrum. Each transfer channel and method is described in detail, and the use of each method is illustrated. There is a discussion of negotiation points for each transfer method.

EMPLOYEE TRANSFER CHANNEL

Many owners of private companies wish to transfer their companies to their employees using the employee transfer channel. Transferring business interests to employees can be accomplished in a number of ways. For example, employees can buy stock directly, be given stock as a bonus, receive stock options, or obtain stock through a profit-sharing plan.

A few key transfer methods in the employee transfer channel are summarized next.

- Employee stock ownership plan is a qualified plan under the Employees Retirement Income Security Act of 1974. An ESOP is a defined-contribution, tax-qualified plan that has two distinguishing features: An ESOP is allowed to invest exclusively in the stock of its sponsoring company, and an ESOP can borrow money. A sponsoring corporation can contribute cash or stock to an ESOP on a tax-deductible basis, increasing cash flow. Owners of private companies can sell all or part of their stock to an ESOP at fair market value, often completely avoiding capital gains tax on the transaction.

- Management buyouts are acquisitions in which a company's incumbent management participates in the buying group. Because management has intimate knowledge of the company's markets and operations, transition issues generally revolve around pricing and financing of the acquisition. Since most management teams do not have the personal wealth to fund the transfer, they typically depend on an outside equity source, such as a private equity group, to raise the money.

- Management buy-ins (MBIs) occur when management teams from outside the target company buy a stake in the company. Normally a private equity group or other financing source backs a key manager or management team who is well known in the particular industry. These incoming managers receive significant ownership and daily operating control. MBIs typically occur when an owner wants to sell but feels that no incumbent manager is suited to own and manage the company. The seller benefits from an MBI because the deal usually is transacted confidentially, quickly, and with a high likelihood of continued success.

CHARITABLE TRUSTS TRANSFER CHANNEL

Charitable trusts enable business owners to transfer their businesses while benefiting from charitable giving. Since the business is the primary asset for most private owners, the disposition of this asset must be maximized. The use of a properly structured charitable trust enables owners to win an estate planning trifecta.

1. The owner transfers all or part of the business while possibly eliminating capital gains on the sale.

2. The owner earns ordinary income for life based on receiving some percentage of the sales proceeds and removes the asset from her estate.

3. The owner's heirs and charity of choice benefit from this technique.

There are two major types of charitable trusts:

1. A charitable remainder trust (CRT) is an irrevocable trust designed to convert an investor's appreciated assets into a lifetime income stream without generating estate and capital gains taxes. Basically, an owner of a C corporation gifts some or all of his stock to a CRT. After the gifting, the CRT can sell the assets or stock of the company to a third party. Since the CRT is a non-taxpaying entity, no capital gains taxes are due from the sale.

When a CRT is established, the beneficiary, who is normally the business owner, receives income from the trust for life or for a term up to 20 years. When the trust ends, the remaining assets pass to the qualified charity or charities of the owner's choice.

2. A charitable lead trust (CLT) is the reverse of a charitable remainder trust. A CLT is an irrevocable trust that provides income to a charity for a specified period of time. The income interest to the charity must either be in the form of an annuity interest (CLAT) or a unitrust interest (CLUT). A CLAT is a trust that distributes a certain amount to a charitable beneficiary at least annually for a term of years or during the lives of one or more individuals living when the trust is created. The remainder of the trust is distributed to or held for the benefit of noncharitable beneficiaries. A CLUT is a trust that distributes a fixed percentage of the net fair market value of its assets valued annually. At the conclusion of the payment term, the CLUT trust property is distributed to the remainder, noncharitable beneficiaries, who can be anyone, including the donor. A number of other charitable trust variations are discussed in Chapter 29.

FAMILY TRANSFER CHANNEL

Transferring a business to the succeeding generation is a realization of an American dream. Although perhaps only 10% to 20% of private businesses actually transfer within the family from one generation to the next, this channel comprises thousands of transfers per year. Numerous methods are used to facilitate transfers to family. Probably more than any other transfer channel, family transfers require a long-term perspective on the part of the transferor, usually the parents, and the transferee, normally the children. There are several explanations for this lengthy transfer time span; most notably, the mechanics of several methods require several years to implement. Further, parents may not wish to relinquish control immediately or may choose to transfer control incrementally. Some of the transfer methods in this world are:

- Gifting stock interests is the most frequently used method of transferring stock in private companies. As of this writing, every person is entitled to give gifts of $13,000 each year to an unlimited number of donees, without incurring any gift tax. This $13,000 amount is adjusted for inflation in thousand-dollar increments. There is no limit on the number of permissible donees. Thus, if the donee has a large family, a significant amount of wealth can be transferred.

- According to Internal Revenue Service regulations, each person has a “unified credit” that allows up to $5 million worth of assets to be transferred during their lifetime and/or death without incurring gift or estate taxes. The portion of the unified credit not used during a lifetime could be used at death. Gifts using the unified credit can be made in addition to gifts using the $13,000 annual exclusions.

- A grantor retained annuity trust is an irrevocable trust that pays an annuity to the term holder for a fixed time period. The annuity typically is paid to the grantor of the trust until the earlier of the expiration of a term of years or the grantor's death. After the expiration of the grantor's retained annuity interest, the trust assets are held in trust for the beneficiaries or paid outright to the remainder beneficiaries.

- Family limited partnerships (FLPs) have become an increasingly popular method for owners of private firms to transfer ownership indirectly to children without losing control of the company. FLPs are a dynamic estate planning tool for four key reasons.

a. Parents control the distribution of cash flow generated by the partnership.

b. Nearly all FLPs make it difficult for the children to sell the partnership interest.

c. Using a partnership entity provides a high degree of protection from creditors. Creditors cannot get to the assets of the FLP or cause distributions to be made to the children.

d. A gift of an ownership interest in an FLP may be made at a lower value than the interest's pro rata share of net asset value because the FLP interest is likely to be noncontrolling and nonmarketable. Thus, discounts for minority ownership and lack of marketability may be applied.

Other transfer methods described in the family channel include self-canceling installment notes, private annuities, and intentionally defective grantor trusts.

CO-OWNER TRANSFER CHANNEL

It is often necessary to buy out a partner. The co-owner transfers channel describes transfer methods available to purchase other shareholders’ equal or unequal interests. Without a written ownership agreement signed by both parties prior to the point of need, a minority interest holder is at the mercy of the controlling shareholder. Further, 50/50 partners without a buy/sell agreement do not have the tools to settle serious disputes. The co-owner transfer channel includes buy/sell agreements, the right of first refusal provision, and other techniques available to transfer shareholder interests to partners. Chapter 31 focuses on several buy/sell provisions, such as Russian roulette and Dutch auction.

OUTSIDE, RETIRE, TRANSFER CHANNEL

Many owner-managers of private companies desire a lifestyle change and want to transfer their business to an outsider and retire. Although the ultimate transfer occurs to an outside investor, some of the transfer methods described in earlier sections can be incorporated into the sale. For example, it is possible to use charitable trusts, private annuities, or grantor-retained annuity trusts as vehicles for the transfer to an outside buyer.

The circumstances and needs of the owner lead to the selection of an appropriate marketing process for the business. The three broad marketing processes are negotiated sale, private auction, and public auction. A negotiated selling process is warranted when only one prospect is identified and the entire process is focused on that prospect. A private auction process is used when a handful of prospects are identified. A public auction process is appropriate when it makes sense to announce the opportunity to the market. The three marketing processes, as well as the players who assist in the transfer industry, are described at length in Chapter 32.

OUTSIDE, CONTINUE, TRANSFER CHANNEL

Some owner-managers of private companies wish to transfer all or part of their business to an outsider but continue operating the business with a financial interest in the business going forward. This condition exists for owners who need growth capital but do not want to bet their personal net worth in the process. To meet these goals, owners have two main choices.

1. They can transfer their business to an outside entity that is consolidating similar companies in their industry. When the consolidation occurs simultaneously with an initial public offering (IPO), the transfer is called a roll-up.

2. When owners transfer a business interest to a company controlled by a private equity group to fund aggressive growth, these transfers are called recapitalizations.

An equity sponsor that builds the company through acquisitions drives a buy and build consolidation. The consolidated company may remain private or go public later. A private seller may or may not have a continuing ownership position in a buy and build consolidation. Chapter 33 illustrates many points for an owner to consider before they take this important step.

GOING PUBLIC, GOING PRIVATE TRANSFER CHANNEL

Going public is the process of offering securities, generally common or preferred stock, of a private company for sale to the general public. The first time these securities are offered is referred to as an initial public offering. Some companies become public by merging with an existing public company. These deals, called reverse mergers, enable a private company to go public more quickly and less expensively than a traditional IPO. Less than 1% of the companies in the United States are publicly held. Yet going public remains the holy grail for a large percentage of private business owners. Chapter 34 describes the processes for going public and going private as well as points to consider before taking the first step.

The goal of this part of this book is to alert private business owners and their professionals to the large number of transfer options that actually exist. Motives of the owner usually lead to the choice of a transfer channel, and each channel comprises numerous transfer methods. The methods enable an owner to convert motives into actions. Because of the technical nature of business transfer, this part is written to give interested players an overview of the structure of various alternatives. Once a road map is conceived, an owner should engage experts in the particular area to tailor a solution to the need.

EXIT PLANNING

The first edition of this book helped launch a new industry called exit planning. Exit planning uses the linkage established in this book:

- Transfer motives or intentions of a business owner lead to a value world.

- Business owners have multiple transfer alternatives from which to choose.

- Specific transfer methods are connected to specific value worlds.

- Therefore, owner motives choose a range of values.

Thus, depending on their transfer motives, business owners actually choose the range of values within which their businesses will transfer. For example, owners motivated to transfer the business to employees via an ESOP receive a fair market valuation, or value determined through application of the hypothetical “willing buyer and seller rule”; those motivated to transfer via a management buyout are more likely to receive an investment valuation, or value that is specific to a particular investor. As is described in Chapter 2, an owner's motive for transferring part or all of the business determines the process by which the business interest is valued. Accordingly, a wide variety of transfer motives leads to a correspondingly large range of possible values for a business.

This discussion assumes that the business is large enough to access a number of transfer alternatives. Many personal service companies, such as a one-person marketing or medical practice, may not have many transfer options. However, a midsize advertising or medical firm may possess numerous transfer alternatives. Thus, financial planners should first assess if the client business has the characteristics necessary to qualify for a variety of transfers. This decision requires substantial experience and may necessitate conversations with other planners, business brokers, or investment bankers.

For exit planning to be effective, planners must be able to help clients identify their financial goals, develop strategies that will promote the realization of those goals, and ultimately execute tactics to achieve the goals. Understanding the linkage between transfer motives and business values empowers planners to help clients develop and execute their financial plans. This knowledge also enables planners to leverage existing skills, which creates value for the client and the planner.

TRIANGULATION

The ability to transfer a business interest is conditioned by the business's access to capital and the value world in which the transfer occurs. The transfer method determines the available choices of capital and often the corresponding value world. Exhibit 26.3 graphically depicts transfer triangulation.

EXHIBIT 26.3 Triangulation

The choice of transfer method may dictate or limit available capital types. For example, ESOPs typically employ bank debt whereas IPOs are linked to equity. Even if the transfer method does not correlate to a capital type directly, the transfer decision often determines the available choices of capital. A management buyout, for instance, qualifies for secured lending as well as mezzanine and private equity group capital. Many family transfers, meanwhile, are implemented without using any outside capital sources. The size of the transaction dictates if it qualifies for many of the government lending programs.

The choice of transfer method affects business value. Regulated transfer methods lead to regulated value worlds; unregulated transfer methods lead to unregulated value worlds. For instance, choosing an ESOP or estate planning technique, such as a charitable remainder trust, puts the seller in the world of fair market value. In contrast, choosing an auction or going public corresponds to market value.

Planning enhances the options available to owners to choose various transfer methods. In fact, the longer an owner plans, the more transfer options become available. Some methods take years to implement. For example, preparing a qualified company to go public may take five years or more. Simpler methods, such as ESOPs, charitable trusts, or private auctions, may take more than a year to execute. However, owners who fail to plan usually have very few transfer options. One elderly owner of a chemical company had for many years intended to form his exit plan. Ultimately his health failed, causing him to spend months in the hospital. The only transfer option available was a low-ball bid to buy the company from a not-so-friendly competitor.