CHAPTER 35

Business Transfer: Conclusion

This chapter concludes the transfer section of this book with a number of observations that build on information provided throughout the preceding chapters. Because the ability to transfer a business interest directly affects the value of a business, owner-managers must understand the ramifications of this value-transfer relationship in the private capital markets. Further, the choice of transfer method often connects with specific types of capital available to support a transfer. The foregoing chapters described the fundamental concepts underlying the transfer of private businesses. This chapter builds on those fundamentals with a discussion of these issues:

- Transfer activity is segmented in private capital markets allowing for an arbitrage opportunity.

- Owner motives choose the range of values available for a transfer.

- Creating value in a private business requires planning.

- Transfer is triangulated to valuation and capitalization.

SEGMENTED TRANSFER ACTIVITY AND ARBITRAGE

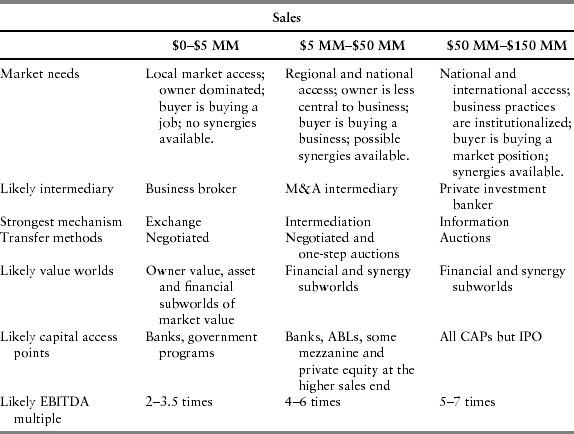

There is no unified transfer market in private capital markets. Rather, the market for transferring business interests is segmented into several levels where the transfer is likely to occur. Each level has more or less access to each of the disparate capital access points, value worlds, transfer mechanisms, and market mechanisms. Each separate shop in the bazaar called the private capital markets can be accessed through various segments or levels. There is an overlap between these transfer segments. For example, different intermediaries assist owners within each segment but may provide services that overlap into other segments. Plus, although certain market mechanisms may be available to all segments, they may be more or less developed within a given segment. Exhibit 35.1 depicts the transfer segments in the lower-middle market.

EXHIBIT 35.1 Segmented Transfer Markets

The three transfer levels roughly correspond to annual sales ranges of less than $5 million, between $5 million and $50 million, and between $50 million and $150 million. Although these market segments can be observed, they are not cast in stone. There are daily variations on the format presented in the table. However, a number of useful perceptions can be drawn from grouping the presentation in this manner.

First, each segment represents salient market needs. Companies with less than $5 million in sales usually transfer locally. However, companies doing more than $100 million may be sold to an international acquirer. Most small companies are sold using a negotiated selling process while larger companies typically transfer using an auction approach.

Second, different groups of intermediaries provide for shareholders’ and investors’ needs at various market levels. Business brokers are likely to arrange transfers at the low end; private investment bankers handle larger deals. There is a fair amount of overlap between the segments. For instance, some business brokers and merger and acquisitions (M&A) intermediaries handle larger deals.

Third, each segment is affected differently by the strength of the underlying market mechanisms. The lowest segment relies on exchange, since these deals are horse-traded events. Further, business brokers have done the best job of creating exchanges in their segment. Some states have multiple-listing-style services for small business sales. Midsize businesses rely heavily on intermediation. Information is opaque in these businesses, and M&A intermediaries must create the information environment for client companies by recasting the financial statement and other means. When combined with the need for confidentiality, with respect to both to the market and employees, these middle deals require a tremendous amount of intermediation. Larger deals leverage existing information. The selling company probably has audited financial statements and accounts for product line profitability using systems that generate numerous management reports. Information regarding potential buyers is also better understood with larger deals.

Perhaps the most interesting aspect of the transfer segments involves the arbitrage play that exists for those who can transact in the proper value world. Buying in one value world and selling in another often creates value. For instance, most consolidators attempt to acquire in the financial subworld of market value and exit either in the synergy subworld of market value or through the public markets. A consolidation math, shown in Exhibit 35.2, can help conceptualize the arbitrage opportunity.

EXHIBIT 35.2 Consolidation Math

| Value World | Selling Multiples | Sales Segment |

| Asset subworld | Net asset value | |

| Investment value world | 2.5–4 times EBITDA | $0–$5 million |

| Financial subworld | 4–6 times EBITDA | $5–50 million |

| Synergy subworld | 5–7 times EBITDA | $50–$150 million |

| Public world | Greater than 10 times EBITDA | Above $150 million |

Some successful consolidations involve buying a group of companies in the asset subworld, merging them into a single operating company, and then selling out in one of the higher-value worlds. But the math still works for investors if the acquisitions are consummated in the financial subworld and the exit occurs in the synergy subworld. It should be noted that selling multiples is often the same in the financial and synergy market value subworlds, but it can be different as well. Exiting at the synergy market level may give the consolidator a slightly higher selling multiple plus a higher synergized benefit stream. This logic behind recapitalizations is further demonstrated in the next example.

One industrial distributor used consolidation math to its advantage in building a fair-size company in a short period of time. The owner noticed that gross profit percentages were falling for his company and his competitors. He reasoned that growth into a medium-size firm would shield his margins and grow his profitability. By using simple math, he was able to determine that companies in the $3 million to $4 million annual sales level would be unable to stay in business in the near term. Consolidating a number of these companies would solve his need for growth and help the owners get out of their investment. He hired an investment banking firm that contacted several dozen of these smaller firms. The investment bankers visited a number of companies and showed them the value-destroying math. Eventually they offered the same deal structure to eight companies: net asset value plus a three-year employment contract. Seventy percent of the purchase price would be paid in cash, with the remainder paid over three years earning 7%. Six of the eight companies agreed to sell representing about $22 million in additional sales.

| Industrial Distributor | ||

| Preconsolidation | Postconsolidation | |

| Sales | $40,000,000 | $62,000,000 |

| EBITDA | 4,000,000 | 8,000,000 |

| Long-term debt (LTD) | 0 | 8,000,000 |

| Minimum market value (5 × EBITDA – LTD) | $20,000,000 | $32,000,000 |

The consolidator gained four things by employing this strategy.

1. It had almost no cash out of pocket to fund these acquisitions. A tier 2 asset-based lender funded most of the required down payment.

2. The consolidator locked up the former owners as managers for several years, which greatly reduced operating risk going forward.

3. With another $22 million in sales, the consolidator was able to renegotiate rebates with vendors adding to profitability.

4. Most important, the distributor centralized accounting, computer operations, and other systems, saving millions of dollars per year.

After the dust settled, the distributor's owner figured he expanded his company dramatically and would recoup his investment in less than two years. Within five years, the owner plans to sell out in the synergy subworld, which is available because his company is now a threat in the marketplace to larger competitors.

OWNER MOTIVES CHOOSE THE RANGE OF VALUES

Private business owners actually choose the range of values within which their business will transfer. This choice of value is manifested by their underlying motives for the transfer, which leads to one or more value worlds. The appraisal process within a value world yields a likely value within a sea of possible values. Once again, private business valuation is a range concept; owner motives just narrow the range a bit. Some of the transfer motives of private owners are listed next.

- Meet personal transfer motives within a business setting

- Diversify their estate

- Create a family legacy

- Use transfer of business as main wealth-creating vehicle

- Grow the business without using personal cash

- Have no partners

Transferring a private business often is complicated because personal and business motives are intertwined. Many owners want to transfer their businesses to their children, yet perhaps only 10% to 20% of all businesses stay within the family. This is an obvious example of the conflict between personal and business motives. These contrasting motives drive the choice of transfer method. This tension causes owners to find a balance between their hearts and their wallets. It also explains the multitude of choices available in the transfer spectrum. A case can be made that because of the impact of owner motives, the private transfer spectrum is vastly more sophisticated than what is available in public markets.

Most private owners sell out because they are burned out. Private owners cannot easily replace themselves, partly because they are control-oriented but also because they tend to wear so many hats that no one person can replace them. This is a key reason why private companies frequently do not outlast the current owner. The private owner usually wishes to diversify her estate, the majority of which is vested in the value of the business. In fact, frequently the business and the personal life of the owner are intimately intertwined. Therefore, a private owner is likely to employ sophisticated estate planning techniques, particularly if her motive is to transfer the business to children as a family legacy. Further, private owners typically forgo some compensation in order to reinvest earnings in the business in the hope that a major capital event will occur someday. Finally, private owners usually are not motivated to sell small parts of their business. The private markets provide little support for this activity, and private owners typically do not want partners anyway.

Ultimately, a motive leads an owner to action. This action, in turn, causes the owner to choose a transfer channel. That choice of a transfer channel directly leads to the choice of a transfer method, which selects a value world. Exhibit 35.3 shows this chain of events.

EXHIBIT 35.3 Linking Motives to Capital

Three interesting observations can be made regarding this causal chain.

1. Channels may house numerous methods, some of which select different value worlds. For instance, the employee channel houses employee stock ownership plans (ESOPs), viewed in fair market value, and management buyouts (MBOs), which may be viewed in market value, investment value, or owner value.

2. The left side of the chart largely involves regulated transfer methods, which lead to the fair market value world. The right side of the chart largely involves unregulated methods, which are viewed primarily in market value. The co-owner channel is the dividing line and can be viewed as part regulated, part unregulated.

3. Channels with multiple worldviews by definition have multiple world values. Thus, an owner wishing to transfer to an outsider and then retire might transact in market value, owner value, or investment value. Each world probably has a dramatically different value proposition.

The value range concept is extended when one considers that some transfer methods may apply to multiple channels, something that is not shown in Exhibit 35.1. For instance, the negotiated transfer method may be employed in the employee, family, co-owner, and outside channels. Or management transfers may occur within the charitable trusts, family, or co-owner channels. Showing all possible linkages would quickly turn the chart into something only Jackson Pollock would recognize. Perhaps a PrivateCo example of this crossover linkage will help.

Assume Joe Mainstreet wishes to transfer PrivateCo to his son and daughter. Because all is well with the Mainstreet, clan the transfer occurs in the family transfer channel. There are other transfer methods that Joe may employ beyond the family methods shown in the previous exhibit. Exhibit 35.4 shows Joe's transfer options, along with PrivateCo's value in the corresponding value worlds as calculated throughout Part One of this book.

EXHIBIT 35.4 Mainstreet's Family Transfer Options

If Joe is motivated to sell PrivateCo to family members, he chooses the family transfer channel. This may employ multiple transfer methods, such as a negotiated deal or the use of various trusts. In other words, Joe always can choose to work out a deal with his children or stay within the confines of a more structured method, such as a grantor-retained annuity trust. The main question is: In which value world will the transaction occur? These methods select four different value worlds, each with a different corresponding value. For this example, PrivateCo's values have been derived in Part One of the book. Joe can choose to transfer PrivateCo to his son and daughter for between $6.8 million to $15.8 million, depending on which value world he selects.

The ability to choose a particular value world in which to transact is similar to possessing a put option. In options lingo, a put is a right to sell something for a particular price at a particular time. The more options an owner has to transfer the business, the more puts she holds. As the range of values in Exhibit 35.2 shows, these puts are valuable. In general, the longer the exercise period and more certain the optioned event, the more valuable the option becomes. The lead time required to execute most transfer methods is not long, at least relative to the life of the business. For instance, implementing an ESOP in a company, arguably one of the most sophisticated methods, usually can be accomplished within one year. Further, most transfer methods are within an owner's control to launch. Other than going public, an owner can plan and execute all other methods.

Options theory may help explain the spectrum of business transfer and its multiplicity of choices. Business owners face a plethora of transfer alternatives. Each alternative has different risks, different values, and different outcomes. Weighting and valuing competing investment opportunities is the task for which options theory was developed. The financial community utilizes options theory on a daily basis. In fact, many companies use real options analysis, which is a technique for identifying and valuing managerial decisions. Although beyond the scope of this work, real options could be employed to better understand and value the options presented on the transfer spectrum.

Well-run businesses can choose from the spectrum of transfer options until late in the game. This is fortunate since most owners procrastinate on transfer issues. The length of time to exercise a transfer option, plus the high certainty of a successful execution, makes these options quite valuable to owners. Planning a particular course of action, based on a motive, is the key to a successful transfer.

CREATING VALUE IN A PRIVATE BUSINESS REQUIRES PLANNING

Company owners should be concerned with creating business value. Often value is not realized from a private business investment until a transfer of the enterprise occurs. Growing businesses are like hungry children: They must be fed. In this case, capital is the sustenance. Many owners choose to suffer personally along the way so their business can remain healthy. If only a transfer unleashes value, what can owners do to increase the value of their firms?

Readers who have read this far will recognize that no single activity is likely to create value in all value worlds. However, if it is possible to plan the value world in which to transact, as the previous section asserts, it is possible to determine how to grow the value of a business. As with most things that really matter, planning is the key.

Chapter 32 introduces the notion of transfer timing. This simply means that timing a transfer is critical to insuring a successful outcome. A multitude of variables must be aligned to enable a successful transfer. Even timing has multiple variables. Transfer timing is comprised of personal, business, and market timing. Transfer timing is like winning on a slot machine. Unless all three timing slots are aligned, the possibility of a big payout is limited. Exhibit 35.5 depicts these three slots.

EXHIBIT 35.5 Transfer Timing

The first slot represents the owner's personal timing. The owner must be physically, mentally, financially, and socially prepared to execute a transfer. The second slot is business timing. Good business timing exists when the company is well positioned to attract positive attention by virtue of its internal operations, management techniques, systems, and financial performance. Market timing refers to the activity level for transferring a business interest in the marketplace. A good market is characterized by aggressive buyer activity in terms of interest levels, acquisition multiples, and available financing. From an owner's perspective, the most successful transfer occurs when all three slots are in alignment.

Generally a less-than-satisfactory result occurs if any timing slots are out of calibration. For instance, owners who are not in a strong personal position to transfer the business may find it necessary to sell at less-than-optimum price or terms. Of course, if the business is not ready to transfer, it is unlikely that outside offers will be attractive to the owner. Finally, the owner and business may be ready for transfer, but if the market does not support the selling process, either the transfer will not occur or it will occur at less-than-optimal price and terms.

Personal Timing

Personal timing is largely within an owner's control. Obviously unexpected problems arise; there is no control over serious illness, accident, or other life-changing circumstances. Yet a good deal of control is possible with adequate planning. The business can be prepared for sale before the time comes when owners want to sell for estate purposes, liquidity, or retirement. Control can be achieved by setting the process in place and planning the event. Personal timing is partially within the control of the individual.

Although some events are beyond control, if the business is prepared for sale, the odds of an attractive sale price are improved. For example, in business cycles, it is possible to anticipate that downturns often follow peaks. If an economic downturn is on the horizon, the business is ready for sale, and personal timing is OK, an owner may control two and a half factors.

Personal timing is difficult to describe because it is different for each owner. The need for clarity in an owner's motive, however, is a commonality for a successful transfer. A number of items constrain an owner's ability to personally plan. Exhibit 35.3 shows some of these constraints.

EXHIBIT 35.6 Personal Transfer Timing Constraints

| Average age of seller in United States | Early 50s |

| Time to prepare a transfer | 1–3 years |

| Average length of employment agreement | 2.5 years |

| Average length of noncompete agreement | 2–3 years |

| Fate of owners over 70 years old | Probable death in business |

| Chances of selling a greedy owner's business | Near zero |

Several constraints affect an owner's personal motives for transferring the business. For example, age is a constraint. The average age for sellers in the United States is approximately 52 years old. This age is down significantly from the prior generation, perhaps as much as 10 years. Either the new economy wears people out faster or baby boomers want to see the world while they are still young. It often takes a year or more to prepare a business for the transfer. Many owners must remain with the business after a transfer for two to three years. Owners who are 70 or older and have no succession plan probably will die in the business. Greed is insatiable. This causes many owners never to leave the world of owner value because no one else on earth values the business as highly as they do. These owners also have a tendency to die in the business, regardless of age. Most smart owners begin planning the transfer at least five years in advance of the transaction.

Business Timing

Preparing a business for eventual transfer is enhanced by knowledge of the value worlds. Simply put, owners can increase the value of their business by choosing the value world for the transfer, then focusing on and maximizing the variables that drive value in the world.

EXHIBIT 35.7 Actions that Affect Market Value

| Goals | Value Drivers | Strategies |

| Increase recast EBITDA | Increase sales | Enter niche markets; patent new products to create barriers to entry; launch innovative products; consolidate competitors. |

| Lower cost of goods sold | Develop scale economies; acquire captive access to raw materials; increase efficiencies in processes (production, distribution, services, and labor utilization); implement cutting-edge cost control systems. | |

| Control operating expenses | Budget and monitor expenses; identify fixed versus variable expenses; manage expenses at lowest level possible; keep track of recast items. | |

| Reduce risk | Increase incremental value | Invest only in positive NPV/IBV projects. |

| Decrease capital base | Withdraw or liquidate underperforming businesses, implement product line profitability capabilities to determine winners and losers. | |

| Reduce business risk | Perform at a higher operating level compared to competitors, long-term contracts, etc.; institute financial transparency; including the retention of audited financial statements. | |

| Reduce cost of capital | Maximize use of debt to support equity; possibly use less costly equity substitutes, such as mezzanine debt; reduce surprises (volatility of earnings); consistently test the market cost of debt; walk down the Pepperdine Private Capital Market Line whenever possible. | |

| Reduce customer concentration | No single customer should account for more than 25% of sales. | |

| Form management structure | Create a functional, possibly virtual, organization so the owner is not central to the business; develop a strong backup manager. | |

| Increase acquisition attractiveness | Develop a place in the market | Always be considered a tough competitor, or roadblock, by larger players; become a company of niches. |

| Obtain critical mass | Achieve minimum sales of least $10–15 million. | |

| Maintain high margins | Focus on maintaining higher gross and operating margins than the competition. | |

| Management team and systems add value | Owner is redundant so management team is considered self-sufficient. | |

| Create effective planning | Build an effective business model that links owner motives to employee actions. |

Most owners should be concerned with increasing their company's market value. Exhibit 35.4 shows a number of variables sensitive to market value. The exhibit shows things owners can do to affect their company's market value. There are three general goals listed, which correspond to the market valuation process. To create market value, companies need to increase recast earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization (EBITDA), decrease the risk of achieving the benefit stream, and generally increase its attractiveness to acquirers. The middle column lists actions that drive value. Finally, strategies are offered that will help owners meet their goals. Several of the value driver items deserve further explanation.

Increase Recast EBITDA

Increasing recast EBITDA is of primary importance since this is the metric that most directly affects market value. Owners can increase sales through internal or external growth, or a combination of the two. In either case, capital is a constraint. Aggressive owners are constantly in search of acquisition opportunities that are accretive and self-financing. This means that consolidation math works in their favor, particularly with a deal structure requiring little or no out-of-pocket cash.

Owners who focus on maximizing their company's gross margins often unlock substantial value. By definition, this means minimizing cost of goods sold. The best investment most owners can make is upgrading the company's purchasing function. Professional materials management pays for itself many times over and helps create market value. Companies can benefit greatly from installing cutting-edge inventory management and other throughput management systems.

Finally, most medium-size companies can create market value by better controlling operating expenses. Unfortunately, many of these companies do not maintain a flexible budget or tie their budgets to longer-term planning. Professional managers, however, are obsessive-compulsive about budgeting at the lowest possible level in the organization and then creating accountability for everyone involved. Ultimately, in most large companies, employee compensation is tied to success against the budget. This contrasts with many smaller private companies, which do not budget sales and expenses. Of course, always reacting to change is a management method that ensures that small companies remain small.

Reduce Risk

Market value increases as a company reduces its operating and financial risk. The starting point here is to manage risk/return by implementing a disciplined capital allocation system. The payback method works well for projects that return the investment within a year or so; however, complicated projects require a net present value or incremental business value approach. Owning a company gets progressively easier and more profitable when assets are deployed correctly.

The single most glaring weakness for most medium-size companies is the lack of vision regarding product and service line profitability. Simply put, many companies do not know where they make money. Outsiders correctly view this lack of control as risky. Once again, companies that budget effectively typically do not have this problem.

Another risk-reducing attribute is the elimination of customer concentrations above 25% or so. Concentrations above 25% are viewed as all-or-nothing accounts by the market and are discounted appropriately. Buyers view management concentration similarly.

Some owners are so central to the success of the business that buyers must plan to hire several additional people to replace them. This situation not only has a negative recasting impact but also adds tremendous risk to an assessment. In either event, concentrations reduce market value.

Increase Attractiveness

There are a variety of actions an owner can take to increase the attractiveness of her firm to the market. It is desirable to be viewed as a market roadblock by larger companies. Larger companies fanatically plan their businesses, especially regarding market share changes. Smaller companies exploit niches that larger companies cannot service effectively. A good value-added strategy for a small company is to position itself in a number of these niches. Larger companies may conclude that it is cheaper to acquire a small competitor than start a market war.

The synergy subworld requires critical mass from its participants. Most sellers cannot access this high-level value world unless they have annual sales of more than $10 million and preferably more than $20 million. Perhaps a perfect situation is a niche company with five to six niches, each selling $5 million to $7 million per year.

Finally, companies with effective business models are always in demand. A business model represents the way an entity is organized to meet a goal. Effective business models are almost always simply stated and understood. The linkage between owner motives and employee actions is taut, which leads to good communications and ability to quickly effect business changes in the market. In many cases, the acquirer adopts many of the business model attributes of the target. For example, a chemical manufacturer was able to convert advanced chemists to technical salespeople, thereby eliminating the need for nontechnical salespeople. A larger chemical company ultimately acquired the company, citing its increased profitability and service capabilities due to a more effective sales force.

How are effective business models developed? Such models start with an intuitive management approach and a keen sense of the market. Beyond this, it is not surprising that many of the strategies that form these business models are the same as the actions that create market value.

Market Timing

Market timing is no less important than personal and business timing. There are opportunities to transfer a business in almost any type of economy. The unexpected knock on the door from an overpaying consolidator, however, happens only to the guy three lockers down. Everyone else must increase their market savvy to realize their goals. To maximize a transfer, a healthy transfer market is a good place to start. The U.S. transfer market seems to run in ten-year cycles, as shown in Exhibit 35.8.

EXHIBIT 35.8 Ten-Year Transfer Cycle

Ten-year transfer cycles represent the macroeconomic market cycle for enterprise transfers. It is no coincidence that the cycle mirrors general economic activity. Transfer cycles begin each decade with two to three years of deal recession. This period reflects an economy in recession that causes banks and other capital providers to lessen lending and investment activities. Large companies tend to focus on core businesses and curtail aggressive acquisition plans. For acquirers with cash, this is a buyer's market.

From a seller's perspective, the prime time to sell a business occurs during the middle years of the cycle. Capital is available for buyers to finance deals during these years. During this period, the MBA crowd has again convinced Wall Street to fund roll-ups and other consolidations. Big companies are back in the game, growing income statements and balance sheets through strategic acquisitions.

The smartest sellers typically wait until near the end of the seller's market before making a move. In this way they get the benefits of increasing profitability plus the highest transfer pricing. Economic storm clouds start forming after eight years or so of the cycle. Because of the economic uncertainty during this period, deals are harder to initiate and close; therefore, waiting too long is risky.

Deal periods in a transfer cycle are not binary switches. Rather, they are like leaky deal faucets. There are opportunities in every period for an owner to create and maximize an exit. However, sellers are most likely to get a good deal in a seller's market.

What is stopping more people from buying in the second and third year of each decade, then selling out in the seventh and eighth years? The answer depends on who they are. Most private business owners are emotionally tied to their businesses, and therefore buying and selling their firms is not something they do routinely. Most private equity groups do not synchronize their activities with the transfer cycle. (Typically this type of thing is not taught in MBA programs.) And large public companies are not concerned with the private transfer cycle.

Obviously, the overall economy in which business operates is not within individual control. However, each industry operates with its own macroeconomic characteristics. By attending industry meetings, reading industry literature, and studying general economic trends, it is possible to assess the health of an industry and where it is in its transfer cycle. With a serious look at the industry and the economy, it is possible to keep informed and exercise some control over when it is best to expose the business to the market.

Maximizing a transfer value usually requires balancing all three elements of timing. But it is somewhat unlikely that an owner is personally ready for a transfer at the same time that the business and market have peaked. It is more likely that a timing trade-off is required. For instance, if the business is growing 30% per year, will it be worth 30% more in a year? Where is the market for business sales and where it is likely to be? If, for example, the business is growing and the economy is declining, interest rates may be higher and the business value to a buyer may decline because financing costs have increased.

Therefore, if the current multiple of earnings is 5, and reduces to 4.5, an owner may have achieved a higher revenue base and profitability but receive a lower market multiple. It is possible to have worked a full year and added no incremental sale price to the business. However, if the economy is strong and growing, then perhaps it is wise to build if it is possible.

A what-if analysis is useful, for example, if the business is valued at $10 million and the owner's target is $12 million. It is possible to develop a plan to increase the business value to meet expectations. This is the art of controlling business timing while factoring in personal goals and personal timing. Business timing is almost entirely in the owner's control. The ancient wisdom here is that from the time an owner acquires or starts a business, he or she should be looking at its sale.

TRIANGULATION

Since most owners get only one shot at the brass ring, they must claim maximum benefits. Positioning for an effective transfer is the key. Yet this chapter shows that this level of planning is a daunting challenge, given the complexity and the multiplicity of transfer options. Continuing with circus analogies, transferring a business is like simultaneously balancing a number of plates spinning on sticks arrayed in a triangular fashion. The critical difference is that the transfer is doomed if just one plate falls. Each plate represents a valuation world, a capital access point, or a transfer method. Owners should understand that the most gifted juggler needs help preparing and implementing the task.

Owners must comprehend the material presented herein on valuation, capitalization, and transfer just to get the plates rotating. Owners should assemble a team with expertise in the respective areas. Keeping the plates spinning and balanced requires almost perfect timing and coordination. An owner needs to form a transfer team to share the load.

In the final analysis, transferring a business involves more art than science. The options include hundreds of possible combinations that could work to accomplish the ultimate objective. However, human folly abounds. Take, for example, a recent incident of an 85-year-old seller who “suddenly discovers” that his 62-year-old son does not want to own the business at exactly the point when the market for business is in its reversionary cycle. Or the rapidly growing cash-strapped $15 million company that chooses to do a reverse merger but still finds it necessary to factor its receivables. Consider the owner who has lived so long in the world of owner value that he has convinced himself it is the only value world that applies to his business. He will always be an owner instead of a seller because he passes up numerous opportunities to sell the business, missing market changes, and ultimately will die in the business or watch as the company goes under.

Selling a business is a process, not an event. The process begins long before any specific event occurs, and there is no second chance with a transfer. The best advice for owners: Clarify motives, choose the channel and methods, form a team, and grab the darn ring.