CHAPTER 5

Asset Subworld of Market Value

Market value is the highest purchase price available in the marketplace for selected assets or stock of the company. Every company has at least three market values at any given moment corresponding to the most likely selling price based on the most likely investor type. These subworlds are asset, financial, and synergy. This is another example of why market value, like all business valuation, is a range concept.

The asset subworld reflects what the company is worth if the selling price is based on net asset value. In this world, the most likely buyer does not base the purchase of assets on the company's earnings stream. The buyer in this subworld does not give credit to the seller for goodwill, the intangible asset that arises as a result of name, reputation, customer patronage, and similar factors, beyond the possible write-up of the assets.

An owner's motive to derive the highest value obtainable leads to appraisals in the world of market value. Commercial real estate appraisers often evaluate the “highest and best use of a property.” Adapting this concept, the world of market value determines the highest and best value for a business. However, the asset subworld shows that the highest value for a business may be found by determining the market value of assets less liabilities.

Financial intermediaries and asset appraisers are the authorities governing the asset subworld, rather than Internal Revenue Service regulations, court precedents, or insurance company rules. Determining value in the asset subworld of market value requires substantial market knowledge, especially in terms of specific asset values.

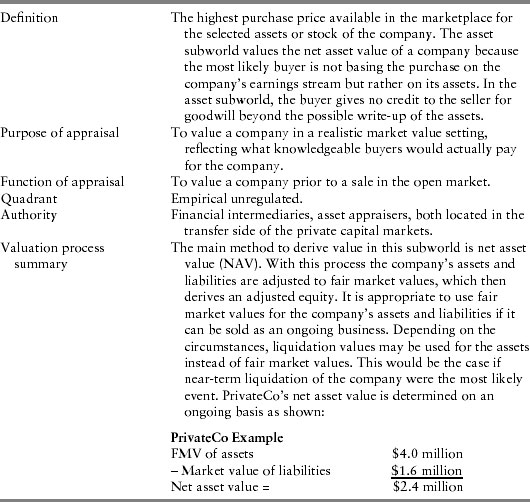

A snapshot of the key tenets of the asset subworld is provided in Exhibit 5.1. The longitude and latitude construct enables the reader to get a fix on the subject matter, especially as it relates the chapter topic to the broader body of valuation knowledge.

EXHIBIT 5.1 Longitude and Latitude: Asset Subworld of Market Value

To derive market value, the first step is to decide which subworld is most appropriate. The guidelines shown in Exhibit 5.2 help determine whether a company's highest value is found in the asset subworld.1

EXHIBIT 5.2 Asset Subworld Is Appropriate if …

|

1. The company has no earnings history and future earnings expectations cannot be reliably estimated. In this context, “earnings” are defined as recast earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization (EBITDA). EBITDA is recast for one-time expenses and discretionary expenses of the owner. This lack of an earnings base prohibits the buyer from using the company's earnings as the basis for the valuation. 2. The company depends heavily on competitive contract bids, and there is no consistent, predictable customer base. 3. The company has little or no added value from labor or intangible assets. 4. A significant portion of the company's assets are composed of liquid assets or other investments (e.g., holding companies). 5. It is relatively easy to enter the industry. 6. There is a significant chance of losing key personnel, which could have a substantial negative effect on the company. 7. The company participates in an industry that does not typically price a goodwill component into the deal structure. This can be the case in certain businesses, such as sawmills, or smaller distributors, such as building material suppliers. |

If the answer to most of the statements in Exhibit 5.2 is yes, then the asset subworld is appropriate to value the company. Typically, however, a company may exhibit some of these characteristics but not all. In these cases, the appraising party should:

- Use judgment as to which characteristics are most important in the context. For instance, the company's lack of recast EBITDA and industry segment are more important considerations than barriers to entry.

- Talk with knowledgeable people in the company's industry about potential buyers. Most industries are serviced by specialist investment bankers and other intermediaries who understand how companies are valued for selling purposes.

Some industries tend toward asset subworld valuations. Buyers tend not to pay goodwill for companies in these industries, especially for transactions less than $5 million. These companies generally are heavily dependent on a key person, usually an owner, are engaged in contract type work, or do not have a reliable recast EBITDA stream. In such cases, a buyer is unlikely to consider paying more than net asset value. Exhibit 5.3 lists types of companies that are typically valued in the asset subworld.

EXHIBIT 5.3 Companies Typically Valued in the Asset Subworld

| Small contractors | Sawmills | Sales representatives |

| Used auto dealers | Small retail | Local hardware stores |

| Small consulting firm | Commodity distributors | Small machine shops |

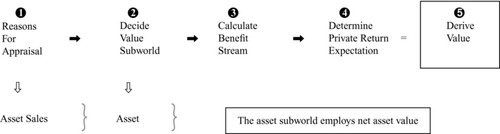

Once the subworld is selected, the next step is to employ a process to derive value. The asset subworld is different from the other subworlds since it does not rely on an earnings stream to derive value. The process for deriving value in the asset subworld is shown in Exhibit 5.4.

EXHIBIT 5.4 Asset Subworld Value Process: Derive Value

Regarding step 5 of Exhibit 5.4, “Derive Value,” there is no need to calculate an earnings stream or return expectation in this subworld because the company is valued on a net asset value basis. With this method, the company's assets and liabilities are adjusted to fair market values, which then derive a net asset value, sometimes known as an adjusted equity. It is appropriate to use fair market values for the company's assets and liabilities if they can be sold as an ongoing business. At times, liquidation values are used to value the assets. This is the case if near-term liquidation of the company is the most likely event.

EXHIBIT 5.5 PrivateCo's Net Asset Value

STEPS TO DERIVE NET ASSET VALUE

Five steps are used to derive net asset value.2

Step 1. Obtain the company's balance sheet as near as possible to the valuation date.

Step 2. Adjust the balance sheet for known missing assets or liabilities.

Step 3. Adjust each tangible asset and identifiable intangible asset to its appraised value, which is generally fair market value. Examples of intangible assets are: patents and copyrights, franchise agreements, goodwill, covenants not to compete, and management or consulting agreements. Patents and franchise agreements usually are carried on the balance sheet at historical cost, which can be substantially different from appraised value.

Step 4. Adjust liabilities to their appraised or market values.

Step 5. After these steps, the amount of total equity is the value of the total stockholders’ equity. If the company has preferred stock or other senior equity securities, then the equity value must be reduced by the value of those securities to determine the value of common equity.

Exhibit 5.5 demonstrates PrivateCo's net asset value determination.

Various assets are restated to fair market values, based on management estimates, real estate, and machinery appraisals. No adjustments are made to the liabilities of the company, which means they must be repaid at face value. In this example, PrivateCo has a rounded net asset value of $2.4 million and a book value of $1 million. The net asset value calculation presumes the assets of PrivateCo could be sold as an ongoing business rather than through a liquidation process. Liquidation values, on either a forced or an orderly basis, can be considerably less than ongoing values.

Income tax adjustments may be required when using the net asset value method. Although the details are beyond the scope of this book, the gains from the asset write-ups may need to be tax-effected. If tax adjustments are considered necessary, they are computed based on the difference between the market value and the tax basis of the company's assets and liabilities. Due to the vagaries and complexities of the tax laws, a pretax stance is taken throughout the book. Readers should confer with their tax professionals on these tax issues.

TRIANGULATION

Market value represents the most direct value linkage from the transfer side of the triangle. Market value authorities, financial intermediaries, and asset appraisers make their livings by transferring assets. They bring this experiential knowledge to the valuation process. For instance, ask any intermediary if they can sell a small sawmill for more than asset value. The answer will be no. In other words, companies viewed in the asset subworld are valued on a net asset value basis because this mirrors the open market.

PrivateCo's value in the asset subworld is $2.4 million.

| World | PrivateCo Value |

| Asset market value | $ 2.4 million |

| Collateral value | $ 2.5 million |

| Insurable value (buy/sell) | $ 6.5 million |

| Fair market value | $ 6.8 million |

| Investment value | $ 7.5 million |

| Impaired goodwill | $13.0 million |

| Financial market value | $13.7 million |

| Owner value | $15.8 million |

| Synergy market value | $16.6 million |

| Public value | $18.2 million |

Market value is located in the empirical unregulated value quadrant, where transactions occur in an unregulated marketplace. Profit-motivated players, free to choose from a host of investment alternatives, form the open market. The authorities then inform the involved parties of the market values based on actual transactions. In the case of competing authorities, such as asset appraisers and financial intermediaries, the authority with the most direct, relevant evidence is heeded. For example, in the asset subworld, the asset appraiser who specializes in an industry segment is likely to be the authority for that segment.

Capital availability directly influences market value. Industries that cannot attract capital tend to suffer from depressed market values and vice versa. This restricted access to capital affects the value at which a company can be transferred. For example, machine shops without proprietary product lines encounter capital restrictions. They may have access to equipment leasing or other asset-based financing but are unlikely to attract mezzanine or private equity. The earnings of the company and personal wealth of the owner are the only sources of growth capital. This condition almost always diminishes a company's ability to increase its market value beyond the value of its assets.

NOTES

1. Jay E. Fishman, Shannon P. Pratt, J. Clifford Griffith, and D. Keith Wilson, Guide to Business Valuations, 9th ed. (Fort Worth, TX: Practitioners Publishing, 1999), Chap. 7.

2. Ibid., pp. 6–7.