CHAPTER 15

Private Business Valuation: Conclusion

Chapters 3–14 cover the concepts underlying private business valuation. These concepts constitute more than a disparate group of approaches to value. Their cohesiveness is due to a number of fundamental theoretical constructs underlying private business appraisal. The concepts of private appraisal are derived, in large part, from risk and return. Consider these facts:

- Private investor return expectations drive private valuation.

- Private business appraisal can be viewed through value worlds.

- Private business valuation is a range concept.

- Valuation is triangulated to capitalization and business transfer.

PRIVATE INVESTOR RETURN EXPECTATIONS

Private return expectations, defined as the expected rate of return that the private capital markets require in order to attract investors, drive private business valuation. The private capital markets house all of the return expectations of private investors. Expected return in this context has many synonyms, including discount rate, expected rate of return, cost of capital, required rate of return, and selling multiples. All are used to describe expected return from a slightly different perspective.

Some observations are important relative to return expectations:

- They emanate from the capital side of the private capital markets triangle. In other words, private return expectations are found in the private capital markets by viewing the Pepperdine Private Capital Market Line (PPCML), as shown in Exhibit 15.1.

EXHIBIT 15.1 Pepperdine Private Capital Market Line

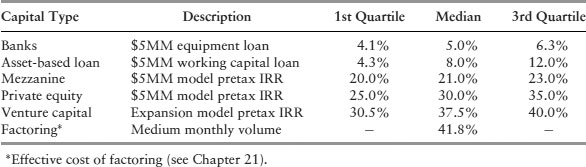

Exhibit 15.1 encompasses various capital types in terms of the provider's all-in expected returns. The PPCML is described as median, pretax expected returns of institutional capital providers. For consistency, the capital types chosen to comprise the PPCML reflect likely capital options for mainly lower-middle-market companies. For example, the PPCML uses the $5 million loan/investment survey category for banks, asset-based lending, mezzanine and private equity. It should be noted that the PPCML could be created using different data sets. The returns are further described as first and third quartiles, as shown in Exhibit 15.2.EXHIBIT 15.2 PPCML Capital Types by Quartiles

The PPCML is stated on a pretax basis, both from a provider and a user perspective. In other words, capital providers offer deals to the marketplace on a pretax basis. For example, if a private equity investor requires a 25% return, this is stated as a pretax return. Also, the PPCML does not assume a tax rate to the investee, even though many of the capital types use interest rates that generate deductible interest expense for the borrower. Capital types are not tax-effected because many owners of private companies manage their company's tax bill through various aggressive techniques. It is virtually impossible to estimate a generalized appropriate tax rate for this market. - Private return expectations can be viewed from at least three different perspectives: market, firm, and investor.

- The market rate is an opportunity cost, which is the cost of forgoing the next best alternative investment.

- An individual firm attempts to meet its shareholders’ return expectations. Firms use their weighted average cost of capital as a minimum return required on investments.

- Individual investors have return expectations that must be met before they will fund an investment. Cost of equity is peculiar to each investor.

Each of these perspectives tells us something useful in the valuation process. - Expected returns convert a benefit stream to a present value. This is valuation distilled to its most basic definition. The ability to derive present values from the universe of investment options is crucial; it enables investors to compare the value of various assets on a common basis. This ability to evaluate investments on a common basis is a building block of valuation and the private capital markets.

Risk and return for private investments should be determined in the private capital markets. The greater the perceived risk of owning an investment, the greater the return expected by investors to compensate for that risk. Due to market inefficiency, risk and return are not perfectly aligned in the private markets. Some capital providers receive a return that is not commensurate with the investment risk. The desire to achieve a return at least commensurate with the corresponding risk is the primary motive for investors to bear the uncertainty of investing.

Many private appraisals performed in the United States look to the public capital markets to determine private return expectations. The capital asset pricing model and buildup methods use public securities information to derive private discount rates. These models presume that the return expectations in the public and private capital markets are the same. A premise of this book is that public and private return expectations are not the same and are not surrogates for one another.

Private return expectations govern all private business valuation. In a sense, they act as a boundary for the private capital markets. A graphic way to conceptualize this boundary is through the PPCML. Risk and return analysis provides the yardstick for the market. In its broadest intellectual sense, all of valuation in the private capital markets can be explained in terms of risk and return.

VALUE WORLDS

Either private valuations must be undertaken, or a transaction must occur to determine the value of a private security for some purpose at some point in time. “Purpose,” also called “reason” in this book, is defined as the intention of the involved party as to why a valuation is needed. Purpose is the starting point in the valuation process.

Motives drive appraisal purpose because a private owner should not undertake a capitalization or transfer without knowing the value of her business. To do so would be the business equivalent of flying blind. For example, without a current valuation, owners cannot effectively raise capital, because they do not know what their assets or business is worth in a lending or investment context. To transfer the business without knowing its worth is usually an exasperating experience.

The purposes for undertaking an appraisal give rise to value worlds. Throughout this book, value worlds are offered as helpful constructs through which to view private business appraisal. Several key concepts describe value worlds. They are:

- One or more authorities govern each world.

- Each world employs a unique appraisal process.

- The choice of world determines the appraisal outcome.

Authority

“Authority” refers to agents or agencies with primary responsibility to develop, adopt, and administer standards of practice within a value world. Authority decides which purposes are acceptable, sanctions its decisions, develops methodology, and provides a coherent set of rules for participants to follow. Examples of authority are found in each appraisal world. For instance, secured lenders are the authority in the world of collateral value.

These lenders are responsible for developing the criteria and administering methodology used to derive value as well as for sanctioning noncompliance.

Another example involves the world of early equity value. Early investors, such as venture capitalists, are the authority in this world since they govern both the rules within the world and the methodology used to derive value. However, for these rules to have meaning outside the investor's view, they must be expressed in communally shared methods and standards. The venture capitalist can sanction noncompliant behavior by not investing in the business. However, for an authority to be effective, it must be widely recognized and accepted. The venture capitalist accomplishes this recognition and acceptance by developing professional management techniques, strategically positioning the company, and adopting generally accepted accounting principles through exercising authority granted in their investment documents.

Authority derives its influence or legitimacy from three primary sources: government action, compelling logic, and the utility of authorities’ actions and standards. The boundary of an authority's influence often does not extend beyond a given value world. Each of these three sources of legitimacy can be found in valuation, as Exhibit 15.3 describes.

EXHIBIT 15.3 Sources of Legitimacy for Authority

There are numerous authorities in every value world. However, some authorities exert more pull on their constituents than others. The nature of an authority's power and pull on its constituency helps position a world in a value quadrant. For instance, the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) and courts regulate fair market value through government action. Since these authorities do not inhabit the private capital markets, their actions may disregard the market's wishes. This lack of market checks and balances on the IRS position causes fair market value to be a notional world. The validity of IRS actions is derived from the extent to which this authority coheres to an intellectually consistent standard rather than the extent to which it corresponds to market activity and mechanisms.

Typically an authority's influence is limited to the value world in which it is viewed. For instance, while state laws and courts make the rules in the world of fair value, they have little or no effect in the other worlds. Likewise, while secured lenders authorize the world of collateral value, they have no standing in early equity value. The limit of an authority's power is a boundary on their influence.

Yet outside parties can influence authorities’ decisions. For example, the business appraisal community has educated and influenced the IRS and tax courts on a wide variety of issues over the years. Along these lines, the author hopes to use the Private Cost of Capital Model introduced in Chapter 10 to standardize the definition of private return expectation in a number of value worlds. This would simplify appraisal as well as make it more relevant.

Competing authorities may cause a world to split into different value quadrants. This is the case for the intangible asset and insurable value worlds. Each primary authority in these worlds derives its legitimacy from a different source. For example, the authority in the subworld of intellectual property—various intangible asset laws—provides a highly regulated influence on the world. In contrast, the subworld of intellectual capital, whose authority is the consulting industry, derives its authority from compelling logic and the utility of its ideas. This authority has an unregulated influence on intellectual capital. In the case of competing authorities, the authority with the stronger claim or more logical argument generally exerts the stronger gravitational pull on the parties. The authority with the stronger veto power is likely to prevail.

Sanctioning is the gatekeeping power of the authority to regulate access to the world. If the intention of the involved party, which leads to a purpose, does not meet the access criteria of an authority, the purpose will not be accepted. For example, an owner who pursues value in the owner value world may not access, or transact in, the world of collateral value. The latter world operates under a different set of valuation rules and will not recognize the owner's treatment of value.

Each World Employs a Unique Appraisal Process

Once the project is located in a value world, the function of the appraisal governs the method by which it is performed. The responsible authority in each value world prescribes these methods. Law, decree, custom, and various other means are used to develop methods. Perhaps the first comprehensive business valuation methodology was developed by the Treasury Department with its Revenue Ruling 59-60. This and subsequent rulings form the basis for valuation in the world of fair market value. Authorities in other worlds are constantly prescribing and proscribing valuation methodology. A new value world, impaired goodwill, was created in 2001 by the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB). As the authority, the FASB created the valuation process in this world. Authorities also proscribe certain methodology. For instance, financial intermediaries insist that asset-based methods are not suitable to value companies in the synergy subworld of market value.

Choice of Value World Determines the Appraisal Outcome

The choice of value worlds may be mutually exclusive. The reason for needing an appraisal selects the appropriate value world. For the most part, reasons point to only one world. Tensions arise because parties within one world might visit another world to accomplish a goal. For instance, an investor in investment value must visit an owner in the owner value world if he wants to acquire the business. The investor and owner are unlikely to agree on a business value, since each party employs a different valuation process. For a deal to occur, the investor and owner probably will need to abandon their own world and value the transaction in the world of market value. The appraisal rules used in market value are less reliant on a particular point of view; rather, the appraisal process attempts to mirror the behavior of the broader market of players.

In some cases, the involved party has a choice as to which value world to employ. For example, an owner operating in the world of owner value can value and transact in her world if she is willing to provide terms that enable the investor to increase his offer. In this case, the owner could offer favorable seller financing to the buyer. The right terms would provide the means for the buyer to pay more for the company without substantially increasing his risk in the deal.

The choice of value world determines the appraisal outcome. This is because each value world employs an appraisal process specific to that world. The range of values exemplifies the effect of using different methodologies in different worlds for PrivateCo. Exhibit 15.4 shows some of the values derived for PrivateCo throughout the chapters. The range of possible values is large, from $2.4 million to more than $18.2 million.

EXHIBIT 15.4 PrivateCo Range of Values

| World | PrivateCo Value |

| Asset market value | $2.4 million |

| Collateral value | $2.5 million |

| Insurable value (buy/sell) | $6.5 million |

| Fair market value | $6.8 million |

| Investment value | $7.5 million |

| Impaired goodwill | $13.0 million |

| Financial market value | $13.7 million |

| Owner value | $15.8 million |

| Synergy market value | $16.6 million |

| Public value | $18.2 million |

Parties that ignore a value world or are confused about the appropriate value world may suffer serious consequences. For instance, if Joe Mainstreet sold PrivateCo in the financial subworld instead of the synergy subworld, he would forgo more than $2 million. Joe might have good reasons to sell his business to a nonstrategic acquirer. At the least, Joe should be aware that choosing a world has an opportunity cost.

The next practical example may help clarify the importance of the two concepts: Private investor return expectations drive valuation, and private business appraisal can be viewed through value worlds. Buyers and sellers are confronted with this situation every day.

EXAMPLE

Joe Mainstreet finds himself in a pressurized situation sitting across the table from people who do not see the value of PrivateCo the way he does. Because Joe cannot understand their position, his only defense is to think the worst of them, and his anxiety builds. He concludes that they want to steal the business he spent a lifetime building.

Fortunately, Joe has Dan Dealmaker with him at the table to act as interpreter and to help overcome natural barriers between worlds. Dan explains that the different value worlds are completely understandable, defensible, and coherent, and all methodologies for deriving value are value-world specific. Dan goes on to say that negotiations improve when the parties are able to understand the motives, worldviews, and methodologies of those sitting across the table. He provides Joe with a toolbox of ideas allowing him to understand the legitimacy of the other positions.

Joe feels some of the tension going out of the situation and says, “I used to worry about the world and all of its people; now I have to worry about the people and all of their worlds.”

Equipped with this new insight, Joe still thinks they want to steal the business … he is just a little less sure of it.

This text does not describe all the known value worlds. In fact, there are many others, limited only by the number of reasons a valuation is needed. For example, real estate is a value world. There is also the issue of value premise to consider. The preceding discussion assumes value on a going-concern basis. Nearly all of the value worlds can be viewed on a liquidation basis, which alters the valuation processes significantly. Although these issues are important, they will be discussed in a future edition.

PRIVATE BUSINESS VALUATION IS A RANGE CONCEPT

Because each value world is likely to yield a different value indication for a business interest, private business valuation is a range concept. Thus, a private business interest has at least as many correct values at a given point in time as the number of value worlds. Within each world there are a multitude of functions of an appraisal that call for unique valuation methods. As Exhibit 15.3 shows, the spread of values can be quite large between worlds.

Beyond the different values determined by world, there are nearly an infinite number of values possible within each world. This observation is based on four factors. First, even though appraisers are interpreters of authority's decisions, there is latitude regarding the application of a prescribed valuation process. For instance, in the world of fair market value, appraisers decide which methods are suitable within the asset, income, and market approaches. This decision-making process causes variability from one appraiser to the next. Most value worlds require judgment regarding the application of methods.

Second, once the appropriate value world is chosen, the next important valuation issue is the calculation of a suitable benefit stream. Each value world employs a different benefit stream to value a business interest. Streams can differ substantially from world to world. Streams also vary greatly from the seller's and buyer's perspective. The difference in the benefit stream definitions in each world is a key reason why value variability exists between the value worlds.

Third, much like benefit streams, private return expectations are determined within each value world. This can be seen by the particular return requirement of an investor in the world of investment value, or to an owner in the owner value world, or to a venture capitalist in the world of early equity. Private return expectations convert a benefit stream to a present value, so they compose one-half of the value equation. Value variability between worlds is increased because each world employs a unique return expectation.

Finally, the probability of different value drivers occurring must be considered. For instance, if PrivateCo's earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization (EBITDA) is $3 million, and this number is used in the valuation, it is assumed with 100% probability that PrivateCo will indeed achieve a $3 million EBITDA. What if, upon further due diligence and consideration of revenues and cost variables, it seems reasonable to presume PrivateCo has only a 50% chance of achieving a $3 million EBITDA? An independent analysis might further indicate PrivateCo has a 25% chance of generating a $2 million EBITDA and a 25% chance of earning $3.5 million. Wouldn't each of these scenarios lead to three different values, even in the same value world?

This concept of value variability is an integral part of the larger idea that business value is a range concept. This is another example where value world theory translates to practical considerations in business valuation and transfer. The concept of ranges provides a way for valuations in various value worlds to overlap in a way that creates the possibility for deals to get done. For example, if parties cannot agree on a specific benefit stream, a deal will not consummate unless an economic bridge is built. Economic bridges come in many forms, such as earn-outs, ratchets, options, look-backs, and other contingent payment plans. These bridges enable parties to come to agreement even though they may still have a foot in their home world. Bridge techniques are covered in detail in Part Three.

TRIANGULATION

A compelling logic holds the three conceptual sides of the private capital market triangle together. Triadic logic provides a powerful cohesion among the moving parts. An idea that originates on the valuation leg of the triangle finds its opposite in the transfer leg and capitalization leg. Triadic logic is a synchronizing function much like harmony in a musical composition. In music, tension is created by the interchange of dissonance and consonance. It is resolved by harmony. Harmony is a logical function imposing a network of transitions, progressions, and modulations to bring opposing forces into a workable system of understanding and communication. The ultimate legitimacy of authorities is the extent to which they contribute to market harmony or equilibrium.

Similarly, triadic logic captures equilibrium in economic theory as markets work to synchronize the thoughts and activities of disparate entities. In a practical sense, this balancing act links private valuation, capitalization, and transfer. Private business value is directly affected by the company's access to capital and the transfer methods available to the owner. Considering the value of a private business interest without reference to capitalization or transfer quickly leads to an unharmonized position.

FINAL THOUGHTS ON VALUATION

Many say that private business valuation involves more art than science. Yet there is a definite structure to this discipline that must be heeded. Active authorities who define suitable valuation processes shape this structure. While some authorities have more sanctioning capabilities than others, involved parties who ignore the structure of this system do so at their own risk.

A private business's value is not fixed; rather, it is relative to the purpose, function, and various other variables of the appraisal. Every private business interest has a range of likely values. The determination of the most likely value from this range constitutes the artful part of the exercise.

Finally, a private value is influenced by a company's access to capital and the transfer methods available to the owner. This interrelationship among value, capital, and transfer is captured in this book by the concept of triangulation. Attempts to value business interests in isolation of the triangulated body of knowledge are similar to sitting on a one-legged stool. It can be done, but most likely it will result in a great fall.