CHAPTER 24

Private Equity

The term “private equity investors” refers to the various individuals and organizations that provide equity capital to private companies. Chapter 23 focused on three early-stage equity investors: business owners, angels, and venture capitalists. The term “private equity,” for our purposes here, refers to institutional entities that mainly provide capital to mainly later-stage companies. This chapter describes several private equity sources: private equity groups (PEGs), hedge funds, and family offices.

In the last 20 years, an organized assemblage of equity providers to companies with revenues in the range of $0 to $1 billion has emerged. Currently, thousands of equity capital providers offer hundreds of billions of capital to private companies. Given the effect of leverage, this investment potential has had an impact on the private equity market several orders of magnitude larger.

Private equity traces its roots to federal government regulations, tax laws, and security laws. For example, the U.S. Department of Labor modified the “prudent man” provision of the Employment Retirement Income Security Act in 1979–1980 to allow regulated pension funds to be invested in private businesses. Increased investment began flowing through the legal structure of limited partnerships, whose investment activities are regulated or governed by their own charters. Those charters typically both prescribe and proscribe the types of investment activities that the limited partners authorize their agents, the general partners, to engage in. Governmental authorities permitted this increased investment. However, the reduction in capital gains taxation from 49½% to 28% in 1978, and subsequently to 20% in 1981, significantly increased the effective return of private equity investments, thereby encouraging increased funds to flow into this market. PEGs, hedge funds, and family offices bring to the private arena the intellectual equipment, language tools, and concepts found in public market companies.

Five characteristics differentiate private equity investing from other types of investing.

1. The private equity investor identifies, negotiates, and structures the transaction. Beyond the transaction, the private investor may be a board member or consultant.

2. The private equity investor has a finite holding period, normally five to seven years. Generally, it takes several years to position the company and at least one to two years to realize a maximizing exit.

3. Private investors seek high returns on their capital. The private investor seeks 25% to 40% returns, as opposed to 10% to 20% return expectations from public equity securities.

4. Private equity professionals invest in a company only when they are convinced that the company's management team can execute the business plan. The conversion from initial idea to profit recognition is the wealth-creating activity, and managers who can successfully conclude this conversion tend to get funded.

5. Most private investors require some control over their investment. This control may involve contractually given rights rather than merely a majority stock position. For example, most private investors negotiate certain rights, such as antidilution, registration, tag-along, and so on. Taken together, these moves grant them a certain amount of control.

STAGES OF PRIVATE EQUITY INVESTOR INVOLVEMENT

There are five generally recognized stages of private equity investor involvement. These stages are important because they enable the equity market to match the appropriate funding source with the capital need, creating efficiency in the capital allocation process. The stages are:

Stage 1: Seed stage. This is the initial stage. The company has a concept or product under development.

Stage 2: Start-up stage. The company is now operational but is still developing a product or service. There are no revenues. The company is usually in existence less than 18 months.

Stage 3: Early stage. The company has a product or service in testing or pilot production. In some cases, the product may be commercially available. The company may or may not be generating revenues and is usually in business less than three years.

Stage 4: Expansion stage. The company's product or service is in production and is commercially available. The company demonstrates significant revenue growth but may or may not be showing a profit. The company usually has been in business more than three years.

Stage 5: Later stage. The company's product or service is widely available. The company is generating ongoing revenue and probably positive cash flow. The company is more than likely profitable and may have been in business for more than 10 years.

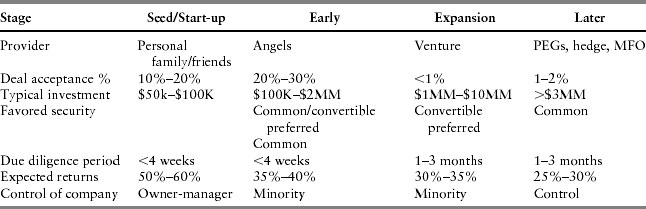

Various equity providers align with each of the five stages of capital needs. Personal and family or friends are the primary funding sources for seed or start-ups. Angel investors invest in early-stage companies that are in business with a product or service in production. Venture capitalists tend to favor expansion-stage companies. Those firms expect to achieve substantial revenue growth, but they have not yet shown a profit. PEGs, hedge funds, and family offices, private companies that manage investments for wealthy families, provide capital for later-stage companies.

Private Equity Groups

A new type of equity investor began in the 1980s and came to prominence in the 1990s. PEGs are the largest direct investors in the equity of private companies, especially in later-stage firms. PEGs tend toward control investments; however, 61% of surveyed PEGs report that with appropriate shareholder protections, they would be receptive to taking minority positions.1

PEGs provide strategic capital for a number of activities, including recapitalizations, leveraged buildups, management buyouts, and management buy-ins. PEGs are opportunistic investors and look at many deals before making an investment. Frequently PEGs will create investment opportunities by sponsoring an executive team to target an industry in which the team has relevant experience and a strong track record. Most PEGs are comfortable investing in family businesses. Exhibit 24.1 displays the capital coordinates for PEGs.

EXHIBIT 24.1 Capital Coordinates: Private Equity Groups

| Capital Access Point | Private Equity Groups |

| Definition | PEGs are direct investors in the equity of private companies, especially later-stage companies. |

| Expected Rate of Return | 25% to 35%, depending on size of deal |

| Value World(s) | Market value |

| Transfer Method(s) | Nearly all transfer methods are supported by PEGs. |

| Appropriate to Use When . . . | Private equity groups provide strategic capital for a number of activities, including recapitalizations, leveraged buildups, management buyouts, and management buyins. Recapitalizations are an ideal transfer method for PEGs because it enables a “win-win” for owner and investor. |

| Key Points to Consider | Few companies qualify for PEG investment. Private equity groups focus on investing in companies with niche, proprietary products or services. Private equity groups tend toward control investments but may make minority investments for deals that meet their expected returns. |

PEG Investment Activities

A PEG's investment activities are divided into four phases:

1. Selecting investments. Includes obtaining access to a high-quality deal flow and evaluating potential investments. This stage involves acquiring a large quantity of information and sorting and evaluating it.

2. Structuring investments. Refers to the type and number of securities issued as equity by the portfolio company and to other substantive provisions of investment agreements. These provisions affect both managerial incentives at portfolio companies and the partnership's ability to influence the company's operations.

3. Monitoring investments. Involves active participation in the management of portfolio companies. General partners exercise control and furnish portfolio companies with financial, operating, and marketing expertise as needed through membership on boards of directors and less formal channels.

4. Exiting investment. Divesting can involve taking portfolio companies public or, more frequently, selling them privately. Because the investment funds of PEGs have finite lives, and investors expect repayment in cash or marketable securities, an exit strategy is an integral part of the investment process.

Like other investors, PEGs assess the general suitability of investment opportunities based on a credit box, shown in Exhibit 24.2.2

EXHIBIT 24.2 Private Equity Groups Credit Box

| Credit Box |

To qualify for private equity group capital, an applicant must:

|

PEGs prefer to invest in companies with niche, proprietary products or services. These companies should enable the PEG to earn above-average returns during the investment as well as create an exit opportunity within five to seven years. About one-third of responding PEGs plan to sell to another private equity group; 29% plan to sell to another private company; 28% plan to exit via a sale to a public company; and the remainder plan to take their companies public or exit in another way.3

Exhibit 24.3 shows various statistics by deal size.4

EXHIBIT 24.3 PEGs Terms by Deal Size

It may come as a surprise to some that PEGs typically do not acquire 100% of the companies in which they invest; rather, they use the equity recapitalization transfer method to make most of their investments. Deal size matters relative to pricing: the larger the deal, typically the larger the acquisition multiple that is paid. Finally, PEGs are using equity for about half of the capital structure, which indicates that at the time of the most recent Pepperdine survey, banks had taken a conservative approach to acquisition lending. If given the choice, most PEGs would prefer a total debt % of the purchase price of 75% or so.

Successful Investment Practices

Bain & Co, an international consulting firm, has identified a handful of disciplines that high-performing PEGs use to add value to their investments.5 Consider the summary in Exhibit 24.4.

EXHIBIT 24.4 Four Disciplines of Top Private Equity Groups

Top PEGs tend to define their investment focus by stressing a few critical success factors. Growth-oriented business plans are the order of the day for these investors. Cash flow, as opposed to earnings, is the key metric. Finally, the investment is divested based on achieving a desired return, even if the exit possibility occurs sooner or later than expected.

After the Investment

PEGs actively tend to their portfolios. For the most part, day-to-day operations are the responsibility of the portfolio company managers. PEGs typically serve as strategic business advisors, assisting management in these activities:

- Developing a strategic business plan

- Organizing and recruiting a well-balanced management team, board of directors, and professional service providers

- Determining appropriate capital structures, arranging equity and debt financings, and providing financial advice

- Developing strategic partnerships

- Planning and executing appropriate exit strategies

- Identifying and evaluating potential acquisition opportunities

Nearly all PEGs have substantial experience helping companies through initial public offerings as well as through merger and sale transactions. Later chapters on recapitalizations and roll-ups further describe the PEG investment model.

The following example describes the PEG investment process.

Example

Joe Mainstreet believes he has an opportunity to grow PrivateCo substantially in a short time. A number of PrivateCo's competitors have approached him about a buyout. Joe believes he can double the size of PrivateCo by buying a handful of these companies and moving all of their business into PrivateCo's existing facility. Joe has been to BankCo, his bank of 20 years, and learned that too much growth is a bad thing, at least from the bank's perspective. On the way out the door, a BankCo vice president introduces Joe to PEGCo, a local PEG.

Joe provides PEGCo with this summary:

| PrivateCo before and after the Acquisitions | ||

| Before | After | |

| Sales | $25.0 million | $45.0 million |

| EBITDA | 3.5 million | 8.5 million |

| Cost of acquisitions | $9.0 million | |

After convincing themselves that Joe's assumptions are correct, PEGCo determines its equity split based on making a $9 million investment in PrivateCo. While in the world of market value, PEGCo determines that PrivateCo is worth about 5.5 times earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization (EBITDA), or $19.25 million, before the acquisition. Following this math, PrivateCo should be worth $46.75 million after the acquisitions. This is equal to about 47% of PrivateCo's equity on a before-acquisition basis ($9MM ÷ $19.25MM), or about 19% of the equity on an after-acquisitions basis ($9MM ÷ $46.75MM). PEGCo has been through these discussions with various private owners before and knows that Joe will fight for every last equity percentage point.

PEGCo expects PrivateCo to increase EBITDA by 10% per year. PEGCo requires a minimum $1 million per year in management fees. Finally, PEGCo believes the business could be sold for $68.2 million in year 5 following an investment ($12.4MM × 5.5).

PEGCo has a 30% return expectation on its investments. Based on the expected fees and terminal value, PEGCo discovers that it must own about 35% of the PrivateCo stock to achieve its desired return. As part of the equity split negotiations, PEGCo also negotiates ownership agreements with Joe to enable it to have a claim on the distributions shown here.

Equity providers have high compounded-return expectations. For the most part, increased risk is correlated with increased return expectations. As might be expected, start-up investor return expectations are the highest, in the 50% to 60% range. Given a five-year investment horizon, a 60% compounded return correlates to about ten times the seed investor's capital. Angels invest mainly in companies that survived the start-up stage and therefore the riskiness has lessened to some degree. Given a five-year horizon, a 40% compounded return correlates to about five times the angel's investment. Venture capitalists and PEGs structure their participation to get 25% to 35% compounded returns on an expected case basis. Once again, using a five-year horizon, a 30% compounded return correlates to about three and a half times the investment. Each group wants to realize much higher returns from the winners in their portfolios.

Five-Year Investment Returns

There is a major difference between the deals that draw venture capitalist (VC) and PEG investment. VCs place bets on business models, that is, on the likelihood that a company's business model will succeed. PEGs, however, place bets on proven management teams. The PEG bet is based on executing a certain strategy, such as a roll-up or other growth vehicle.

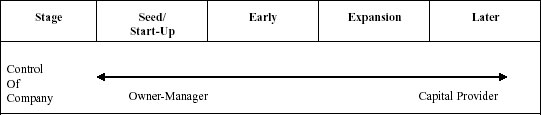

The next control-of-company spectrum shows that the owner-manager normally has operating and legal control in the early years of the company. This may change as the company's funding needs grow.

HEDGE FUNDS

Hedge funds are rather recent players in making investments in private companies. A hedge fund can take both long and short positions, use arbitrage, buy and sell undervalued securities, trade options or bonds, and invest in almost any opportunity in any market where it foresees impressive gains at reduced risk. Hedge fund strategies vary enormously—many hedge against downturns in the markets—which is especially important today with volatility and anticipation of corrections in overheated stock markets. The primary aim of most hedge funds is to reduce volatility and risk while attempting to preserve capital and deliver positive returns under all market conditions. While most hedge fund activities involve trading in public markets, hedge fund managers increasingly view larger private company securities as a potential source of returns.

The first hedge fund in the United States was set up by Alfred W. Jones in 1949. Jones was the first to use short sales and leverage techniques in combination. In 1952, he converted his general partnership fund into a limited partnership investing with several independent portfolio managers and created the first multimanager hedge fund. In the mid-1950s, other funds started using the short-selling of shares, although for the majority of these funds, the hedging of market risk was not central to their investment strategy.

Hedge funds traditionally have been limited to sophisticated, wealthy investors. Over time, the activities of hedge funds broadened into other financial instruments and activities. Today, the term “hedge fund” refers not so much to hedging techniques, which hedge funds may or may not employ, as it does to their status as private and unregistered investment pools. As of this writing, there are more than 8,000 registered hedge funds, with more than $1 trillion assets under management.6

The following further describes hedge funds:

Key Characteristics of Hedge Funds7

- Hedge funds utilize a variety of financial instruments to reduce risk, enhance returns, and minimize the correlation with equity and bond markets. Many hedge funds are flexible in their investment options (can use short selling, leverage, derivatives such as puts, calls, options, futures, etc.).

- Hedge funds vary enormously in terms of investment returns, volatility, and risk. Many, but not all, hedge fund strategies tend to hedge against downturns in the markets being traded.

- Many hedge funds have the ability to deliver non-market-correlated returns.

- Many hedge funds have as an objective consistency of returns and capital preservation rather than magnitude of returns.

- Most hedge funds are managed by experienced investment professionals who generally are disciplined and diligent.

- Pension funds, endowments, insurance companies, private banks, and high-net-worth individuals and families invest in hedge funds to minimize overall portfolio volatility and enhance returns.

- Most hedge fund managers are highly specialized and trade only within their area of expertise and competitive advantage.

- Hedge funds benefit by heavily weighting hedge fund managers’ remuneration toward performance incentives, thus attracting the best brains in the investment business. In addition, hedge fund managers usually have their own money invested in their fund.

Converging with Private Equity Groups

Hedge funds are almost always opportunistic investors, meaning they typically do not have a static credit box like other equity investors. In fact, hedge funds value liquidity more than other equity players and normally will make an investment in a private company only if the exit strategy is apparent. Exhibit 24.5 compares hedge funds and PEGs on a number of investment factors.

EXHIBIT 24.5 Hedge Funds versus Private Equity Groups

| Hedge Funds | Private Equity Groups | |

| Due diligence | Quick based mainly on the metrics of the security and exit | Slow based on a large number of factors, including management and industry |

| Holding period | Usually less than 18 months | Usually 5–6 years |

| Participation | Yield players, may not be actively involved | Strategic investors, certain to be involved |

| Risk tolerance | High | Medium |

| Return definition | Return is based on the difference between invested value and sales proceeds. | Return on an investment may be adjusted based on several factors, including market share, profitability, revenues and valuation metrics. |

| View of financial metrics | Only metrics that directly convert an investment to a return are important. | A variety of financial metrics are important and monitored. |

| Management fees | Set based on the company's ability to pay; probably more aggressive than PEGs | Typically 2% management fees |

Private equity firms generally invest in a company's equity, with a long-term view seeking large “equity-upside” returns. Hedge funds, however, may invest in secured debt, unsecured debt, or equity and may hedge those investments through intracompany hedges or industry hedges while seeking extraordinary returns. The hedge fund exit strategy may be a simple trade, as opposed to a complete corporate disposition. However, when loan-to-own hedge funds invest in debt securities of portfolio companies owned by private equity funds, the different risk tolerance, hold periods, and leverage and liquidity issues of the funds inevitably will result in a culture clash.

Approaching Hedge Funds

Even though there are thousands of hedge funds, it can be difficult to approach this group with an investment opportunity. Hedge fund managers tend to deal only with existing relationships. These managers are not in the position or inclined to perform long due diligences. Further, since hedge funds do not always employ consistent credit boxes, it is best to contact them through an intermediary that they already know.

FAMILY OFFICES

A family office is the organization that is created, often after the sale of family business or realization of significant liquidity, to support the financial needs (ranging from strategic asset allocation to record keeping and reporting) of a specific family group.

The modern concept and understanding of family offices was developed in the nineteenth century. In 1838, the family of J.P. Morgan founded the House of Morgan, which managed the family's assets. In 1882, the Rockefellers founded their family office, which exists today.

No formal data exists, but it is estimated that there are between 2,500 and 3,000 family offices in the United States; perhaps another 6,000 exist informally inside privately controlled businesses in the United States. For Europe and Asia, the concept of a family office is just evolving, with new family offices being formed monthly in these areas.

Family office services vary depending on the goals of the office. Some offices offer strictly strategic and investment services while others offer everything from strategic to convenience services like travel planning. Most offices provide these services:

- Investment advice, management, monitoring

- Financial and tax planning

- Wealth transfer planning

- Financial record keeping and compliance

- Family foundation management

- Client education and goal development

There are two types of family offices: single-family offices (SFOs) and multifamily offices (MFOs). SFOs serve one wealthy family, while MFOs operate more like traditional private wealth management practices with multiple clients. MFOs are much more common because they can spread heavy investments in technology and consultants among several high-net-worth clients instead of a single individual or family.

MFOs tend to have these characteristics:

- Independence. MFOs typically do not sell traditional products that a family typically might encounter from a brokerage firm and generally are not compensated for the products utilized by clients. MFOs usually follow a service delivery model, holding themselves out as an objective provider of advice that places the interests of their clients first.

- Breadth and integration of services. MFOs provide a wide array of services and typically oversee their clients’ entire financial universe. MFOs will have full information about their clients’ investments, tax situation, estate plan, and family dynamics. With this information, MFOs can assist in structuring and administering the clients’ financial universe in an optimal fashion.

- Professionals with diverse skills and deep specialties. MFO professionals provide a wide array of advice and assistance to their clients. MFOs also have to be able to provide specialty knowledge on certain topics, such as income taxation, estate planning, and investments.

- High-touch services. MFOs have high average account sizes (usually in the tens of millions) and low client-to-employee ratios (in around the 3-to-1 range). Large account sizes combined with low client-to-employee ratios allows a great deal of focus and attention on each client family. Meetings with clients often occur many times a year.

- Multigenerational planning. MFOs typically work with an entire family: the patriarch/matriarch, their children and grandchildren. Planning encompasses the family's goals, which typically includes passing wealth down to younger generations in a tax-efficient manner. Children and grandchildren are clients and are counseled on investments, taxes, estate planning, and philanthropy from an early age. MFOs often coordinate and moderate family meetings for their client families.

- Outsourcing. MFOs do not typically provide all services in-house. It is common for some of the investment management to be outsourced to independent money managers. Custody and tax return preparation are also commonly outsourced.

- Focus on taxable investor. Most MFOs have a myopic focus on taxable investors, as the bulk of their client's assets are subject to short- and long-term capital gains. This is unique to very-high-net-worth families. Most investment research (academic and financial service industry) is geared toward the institutional investor and foundations (with very different tax concerns from those of individuals and families). The bulk of the research done for the individual investor relates to 401ks and Individual Retirement Accounts.

Family offices have trillions of dollars in assets under management and will likely play a more meaningful role in private equity going forward.8

TERM SHEET

In the world of private equity, the term sheet outlines the tenets of the deal. The term sheet summarizes all the important financial and legal terms in the contemplated transaction, and it quantifies the value of the financing. Although generally a legally nonbinding agreement, the parties have an implied duty to negotiate the term sheet in good faith. Ultimately, an executed term sheet serves as the basis for the legal documents. Most of the terminology used in term sheets is the same whether the deal involves an angel, venture capitalist, or private equity group. Appendix E contains an example term sheet for a preferred stock financing.

The process of preparing and negotiating a term sheet helps to solidify the transaction and create a sense of momentum between the parties. A well-drawn and complete term sheet helps to minimize the time and efforts required to draft and negotiate the final agreements. In addition, an executed term sheet often assists the company in its negotiations with lenders, creditors, suppliers, customers, and others. A number of issues need to be negotiated between the parties, some of which are highlighted in the next sections.

Exhibit 24.6 compares various private equity sources based on a number of different criteria.

EXHIBIT 24.6 Comparison of Private Equity Investors

The exhibit depicts the three institutional private equity providers relative to the investment stages and other criteria. There is some overlap between the providers and the stages (i.e., some venture firms invest in early- or later-stage deals, while some angels may get involved with start-ups).

Angels accept a larger percentage of the deals they are presented than do VCs and PEGs. This can be explained in two ways.

1. Angels do not get to see as many deals as the institutional investors, so the universe of deals they look at is smaller.

2. Angels often have nonmonetary reasons for making an investment, such as personal connection to the founder.

Typical investment sizes vary dramatically from one investor type to another. There is an overlap among the institutional providers. Unless there is an organized angel group involved, it is unlikely that more than $1 million to $2 million will be invested. Due to large amounts to invest, it is difficult for a VC, PEG, or hedge fund to invest less than $2 million to $3 million in a business for the deal to be worthwhile.

NEGOTIATING POINTS

Investees, the companies possibly receiving the funds, should not begin to negotiate a term sheet with private equity investors until they understand the offered terms. This is also a good time to get legal and other professional advice. The entire deal should be fully considered before specific clauses or provisions are discussed. Once the deal is understood, investees can expect to negotiate the next points.

Process of Developing the Valuation

Different investors value an interest quite differently, depending on their understanding of the risk of the investment. Investees should not negotiate a value or price offered for their shares until they understand the process used by the prospective investor. Even after the process is well understood, the valuation process should be negotiated rather than the final value.

Managing Multiple Offers

It is difficult to run auctions or other methods of generating multiple offers from equity investors. Part of the problem is that institutional investors talk to each other and often syndicate their deals. Another constraint is the time required by the investee to initiate and manage multiple offers. Managing multiple offers is more likely to be successful if the investee has engaged a representative. Even with professional assistance, it is probably wise to deal with investors who are widely separate geographically.

Board and Governance Issues

When investors have legal control, the board is mainly ceremonial. Minority equity investors often want the right to appoint a designated number of directors to a company's board. Doing so enables investors to better monitor their investment and have a say in running the business. Companies often resist giving equity investors control of, or a blocking position on, a company's board. A frequent compromise is to allow outside directors, acceptable to the company and investors, to hold the balance of power. Occasionally, board visitation rights, in lieu of a board seat, are granted.

A variety of governance issues should be described in the term sheet. These were discussed in Chapter 23.

Vesting of the Founders’ Stock

Equity investors often insist that all or a portion of the stock owned or to be owned by the founders and key employees vest only in stages after continued employment with the company. This condition is often called an earn-in of stock. This can be an important issue even for later-stage companies when the value of the company is high. If forced to earn-in over time, managers should negotiate benchmarks that are within their control to achieve without further actions by the equity investor.

Employment Agreements with Key Founders

Management should negotiate employment agreements as part of the funding. Key issues often are compensation and benefits, duties of the employee and under what circumstances those duties can be changed, the circumstances under which the employee can be fired, severance payments on termination, the rights of the company to repurchase stock of the terminated employee and at what price, term of employment, and restrictions on postemployment activities and competition.

Special care should be taken to tie the employment agreement to the buy/sell agreement. For instance, if a manager is terminated without cause, that manager's stock should be repurchased at full value. However, if the manager is terminated with cause, the shares probably will be repurchased at a discount to full value. Managers should also negotiate to have the company pay for life and disability insurance that will fund the employment agreement and buy/sell.

Investor Transfer Rights

A number of investor transfer rights are negotiated. Some of these are:

- Preemptive rights. The right of the investor to acquire new securities issued by the company to the extent necessary to maintain its percentage interest on an as-converted basis.

- Registration rights. Investors typically receive certain registration rights for public offerings. Negotiations center around whether the investor receives piggyback and/or demand registration rights, and who pays the expenses of each such registration. Piggyback rights allow the investors to have their securities included in a company-initiated registration. Demand rights mean that the holder can require the company to prepare, file, and maintain a registration statement. Normally, investors require the company to pay all of the holder's expenses regarding registrations.

- Right of first refusal. Right of the investor to be first offered securities to be sold by other shareholders and/or the company.

- Right of cosale. Right of the investor to sell its securities along with any securities sold by the company or the other shareholders.

- Tag-along or drag-along right. Right to obligate other shareholders to sell their securities along with securities sold by the investor.

These rights should be set forth in the term sheet and generally terminate upon an initial public offering of common stock by the company.

No Shop

Equity investors often insist on a no-shop period at the term sheet stage when the investors have a period of time (usually 30 to 60 days) where they have the exclusive right, but not the obligation, to make the investment. Viewed from the investee's perspective, it is the period within which the company or its agents cannot solicit other investor interest. The prospective investee does not want to grant such an exclusivity period, as it may prevent it from obtaining financing if the parties cannot reach agreement on a definitive deal. Ultimately the investee probably will agree to some no-shop period, which should not surpass 60 days. An investee might negotiate a benchmark for this no-shop period. For instance, at the end of 30 days, equity investors must sign off or release some part of their due diligence (e.g., the operating agreement or employment agreements must be agreed to in principle). If these agreements are not resolved at that point, the company can shop the deal again.

Private equity sources in the United States are sophisticated providers of various kinds of capital. Angels, venture capitalists, and PEGs tailor investments to achieve certain purposes, all leading to an expected return. The difficulty of generating these high returns cannot be overstated. Very few private companies can produce 30% compounded returns over a long period of time. This chapter shows that owners who wish to raise private equity should do so with great care.

TRIANGULATION

Private equity investors provide various types of capital to growing companies. The various equity providers align with the four stages of capital needs. Angels, venture capitalists, and PEGs typically invest in early-, expansion-, and later-stage companies, respectively. Many companies evolve from one capital provider to the next, as their capital needs change.

Companies in need of private equity are viewed in the world of market value. Value world collisions are the norm when private equity is sought. Founders and other shareholders tend to view value from the owner value world perspective, which often results in an overvaluation, at least from the perspective of the particular private equity provider. Many deals fail because this collision cannot be reconciled.

Family offices are an emerging player in private equity. They may be the perfect example of an investor that can maximize triangulation. They have access to substantial amounts of investible funds; their clientele typically has made or currently is making money from business ownership —so they have value creation and transfer know-how as well as vital global connections; and they can afford to take a longer-term view than the other private equity players. No other group can integrate capital, valuation, and transfer as effectively as family offices.

The goal of private equity is to produce significant value from investments. PEGs, hedge funds, and family offices share this mission. Each group uses different tactics to achieve this goal, however. A particularly interesting tactic involves PEGs and recapitalizations. In a recapitalization, an owner transfers most of the business to a company controlled by a PEG, which then funds an aggressive growth plan. This strategy allows an owner to sell the business twice: once to the PEG and once to the open market.

One manufacturer of highly engineered narrow woven fabrics chose a recapitalization structure to have enough capital to consolidate a segment of the textile industry and to partner with an investor who had a successful track record of growing companies and creating maximizing exit plans. Together, the original owner, with the backing of the PEG, acquired a number of smaller industry players and doubled the business in two years. Soon after this the partners were able to exit the business via a sale to a much larger player at a much higher-selling multiple than was possible as a small company.

From the moment a company receives private equity, it is in play to be transferred. Private equity providers are driven to invest by the probability of successful exits. They negotiate deals that increase the odds of a profitable transfer. As a last resort, the provider will transfer its shares back to the company at some future date. The more profitable exit for the investor, however, usually involves a public offering or sale to a synergistic acquirer. This can be another source of friction between shareholders and investors: Shareholders may wish to grow and hold, while investors want to grow and harvest. Both parties need to understand the other's motivations and plan accordingly.

NOTES

1. John K. Paglia, Pepperdine Private Capital Markets Project Survey Report, April 2010, bschool.pepperdine.edu/privatecapital.

2. Ibid.

3. Ibid.

4. Ibid.

5. Mark Long, Raising Capital (San Diego:Promotions Publishing, 1998), pp. 129–130.

6. Mark K. Thomas and Peter J. Young, “What Commercial Borrowers and Lenders Should Know about Private Equity vs. Hedge Funds,” CapitalEyes (April 2006).

7. Taken from: www.magnum.com.

8. Ibid.