CHAPTER 33

Outside Transfers: Continue

Many owner-managers of private companies wish to transfer all or part of their business to an outsider, but they plan to continue operating the business for the foreseeable future. Some owners want to continue to have a financial interest in the business going forward. Frequently they need growth capital but do not want to risk their personal net worth in the process. Owners can choose between two primary transfer methods to meet these goals.

1. They can transfer their business to an outside entity that is consolidating similar companies across the industry. When the consolidation occurs simultaneously with an initial public offering, the transfer is called a roll-up.

2. Owners can choose to transfer most of their business to a company controlled by a private equity group, which then funds an aggressive growth plan. These transfers are called recapitalizations.

This chapter describes these two transfer methods.

Even though the ultimate transfer occurs to an outside investor, some of the transfer methods described in earlier chapters can be incorporated into the sale. For example, it is possible to use charitable trusts, private annuities, or grantor-retained annuity trusts as vehicles for the transfer to an outside buyer. Many owners hire a business broker, mergers and acquisitions intermediary, or investment banker to assist in arranging the outside transfer. Further, the transfer processes described in Chapter 32 can be used to market the company to roll-up and recapitalization investors.

Discussing the nature of consolidations is a useful starting point for understanding outside transfers.

CONSOLIDATIONS

Consolidations involve the initial acquisition of one or more platform companies, followed by the purchase of add-on acquisitions. If the consolidation occurs simultaneously with an initial public offering (IPO), it is called a roll-up or a poof IPO. More common is the buy-and-build strategy, which uses private equity and debt for the initial acquisitions. “Buy and build” is the term used in the private equity industry for this method of consolidation. The participating owner, normally the owner of a platform company, might refer to this method as a recapitalization. Consolidations occurred in the first decade of this century in a wide variety of industries, such as metal distributors, staffing services, auto dealerships, and heating, ventilating, and air conditioning services.

Common characteristics of consolidations are

- High industry fragmentation.

- Substantial industry revenue base.

- Mature industry with decent profit margins.

- No dominant market leader and few, if any, national players.

- Critical mass is achievable with a manageable number of acquisitions.

- Achievable economies of scale.

- Ability to increase revenues with national coverage or brand.

- Large universe of willing sellers with profitable operations.

The ideal industry for a consolidation has one added characteristic—no existing consolidation players. The first consolidator should be able to scoop up the best companies and managers.

A consolidation creates numerous opportunities for earnings improvement of the consolidator.

- Cost cutting. Consolidations create redundancies. Eliminating these redundancies is a primary source of earnings improvement for these deals. There are surpluses in staff, administrative, and back-office functions, such as computer systems. Consolidators can obtain volume discounts and other vendor cost concessions in a wide range of areas.

- Revenue growth. The combination of acquisitions and organic growth enable consolidators to grow quickly. This growth is aided if the consolidator reaches critical mass by becoming large enough to service its industry on a national basis. In many industries, national companies have an advantage over smaller competitors.

- Key management. A successful consolidator often attracts the top managers in its industry. The combination of a high compensation package and opportunity to change the industry is often irresistible. These professional executives usually have experience managing hypergrowth situations.

- Benefits of size. Benefits accrue to the largest player in an industry. Aside from the ability to develop national accounts and attract the best employees, the consolidator may benefit from added rebates from vendors and the ability to create integrated systems and to establish national brands.

CONSOLIDATIONS

- Roll-up. Consolidation occurs simultaneously with an initial public offering. Sometimes called a proof roll-up. The original sellers trade control-level private equity for cash and a minority position in a public entity.

- Buy and build. An equity sponsor builds the platform company through acquisitions. The consolidated company may remain private or go public later. The equity group calls these “buy-and-build consolidations.” A private seller may or may not have a continuing ownership position in a buy-and-build consolidation.

- Recapitalization. Shareholders transfer most of their business to a company controlled by a private equity group, which then funds an aggressive growth plan. A private company in a recapitalization may be the platform firm. The seller will have an equity stake going forward in a recapitalized company.

A consolidation can create a company that dominates smaller competitors. Exhibit 33.1 provides the transfer matrix for consolidations.

EXHIBIT 33.1 Transfer Matrix: Consolidations

Pricing Arbitrage

The old investment axiom of “buy low, sell high” drives the public exit for many consolidations. A “private/public” pricing arbitrage opportunity is available to consolidators. Consolidators, from various industries, typically pay an average of about five to six times trailing recast earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization (EBITDA) for acquired companies. By going public, those same consolidators may be able to resell those adjusted earnings at a multiple of 10 to 15, or more, depending on the industry. This private/public arbitrage allows consolidators to pay top prices for acquired companies. It also enables equity investors and lenders to achieve risk-adjusted returns on consolidation plays.

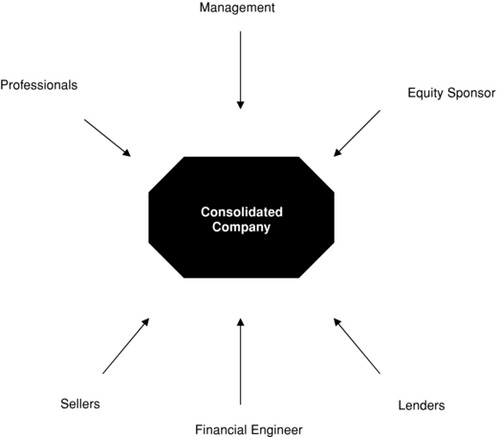

Players

A variety of participants are involved with creating and managing consolidations. These players are described in Exhibit 33.2. All of these players’ movements must be orchestrated for the consolidation to succeed. The financial engineer arranges the activities, from valuing the various companies to determining the equity splits. Sometimes this engineer is an investment banker. The engineer attracts the equity sponsor to the consolidation and arranges the necessary debt. Most important, the engineer negotiates the first platform deal, which usually sets the tone for the consolidation. The key managers are hired early in the process. Part of the duties of these managers may include attracting other sellers to the consolidation. Various professionals, including lawyers and accountants, are required to assist with the deals. If the consolidation is taken public, an underwriter has a large voice in its structure.

EXHIBIT 33.2 Consolidation Players

ROLL-UPS

A roll-up is the consolidation of several smaller businesses into one large operation, which is simultaneously taken public. A roll-up starts with an investment banker identifying several private companies operating in the same industry that wish to sell their businesses for some combination of cash and stock. A deal is created by which the owners of the founding companies agree to sell and be paid from the proceeds of the initial public offering of the newly created entity. A roll-up company is formed to acquire each founding company and initiate the IPO. Under typical buyout agreements, owners receive a combination of cash and stock in the newly formed company. Frequently, a portion of the debt also is paid off at this time. IPO proceeds also may be used to pay the firm that helped form the company. Founders who own platform companies often get the best price for their businesses.

Initial Public Offering

Going public is critical to consolidators for a number of reasons. The IPO provides the currency for add-on acquisitions because consolidators prefer to pay in stock instead of cash. There is a tax incentive for owners to do at least a 55% stock-for-stock exchange, since no capital gains taxes are triggered on that portion of the transaction. Of course, the downside to sellers is that they lose control over the stock price and probably will have restrictions on their ability to sell their position in a timely fashion. In addition, the IPO enables the realization of the earnings arbitrage mentioned earlier. Moreover, the IPO provides the promise of a large return for the equity sponsors and investors.

After the IPO

The primary challenge after the IPO is for the management team to integrate the acquisitions and impose the earnings discipline of a public company. The integration process is especially problematic, since the add-on acquisitions are not easily meshed into platform entities. The easier part of the integration is cost cutting of duplicate expenses. Unfortunately, many employees of the consolidating company may lose their jobs. The extent to which the former owners invest their energies and ambition in the consolidated company determines the ultimate success of the roll-up.

Roll-Up Performance

The 1990s were a roll-up heyday. More than two dozen industries were consolidated using this method. The financial performance of these roll-ups has been poor. One study examined the motivations and economic impact of 47 roll-ups initiated from 1994 and 1998.1 It found that the long-term stock price performance substantially lags that of several benchmarks. While the operational performance of these roll-ups is no different from other firms in their respective industries, their initial valuations indicate that expectations were much higher. The firms in the sample fail to meet analysts’ expectations, on average.

Roll-Up Points to Consider

Participating in a roll-up is a fairly high-risk endeavor, especially for the sellers. Potential sellers should consider the next points before signing up.

- Many consolidations do not succeed. For private owners to relinquish control over their company and plug into a public entity requires a leap of faith. Many owners are better off plotting their own independent course.

- If an owner is determined to sell into a roll-up, it is best to sell early in the process. The owner with a platform company usually gets the best deal.

- Owners should not settle for a pure stock-for-stock transaction with the consolidated company. They should receive enough cash to meet their minimum estate-planning requirements.

- Owners should pick their partners carefully. There is no substitute for experience. Some financial engineers and equity sponsors have better track records than others.

The best advice: Be wary of roll-ups because their risks may be too great to measure adequately.

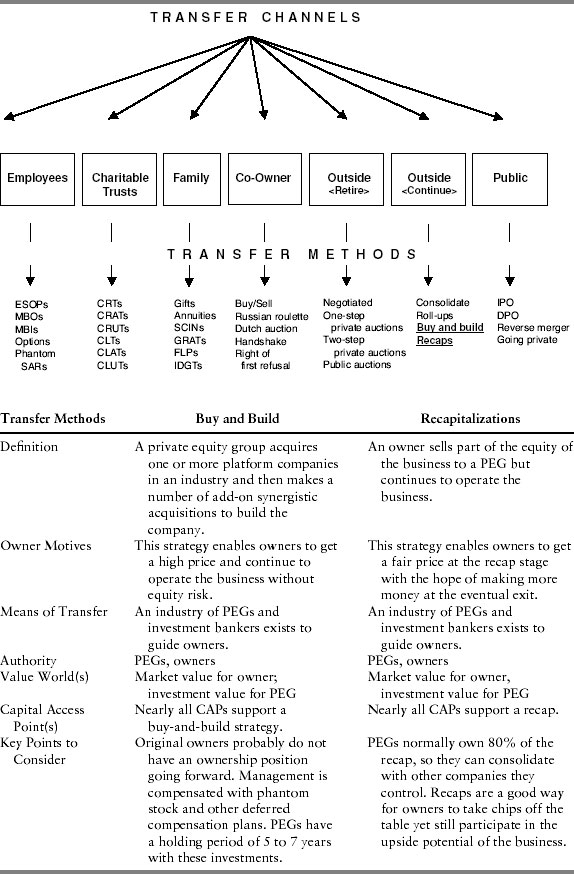

BUY AND BUILD OR RECAPITALIZATIONS

The buy-and-build or recapitalization strategy is a more prevalent method of consolidating companies in an industry. Exhibit 33.3 shows the transfer matrix for buy and build and recapitalizations. The difference between buy and build and recapitalization is the perspective of the player; owners view it as a recapitalization while private equity groups (PEGs) view it as a buy and build. The buy-and-build strategy is a central business model for many PEGs. Most PEGs employ this strategy and may or may not eventually take the consolidated company public, depending on which alternative avenue maximizes their exit. A PEG usually acquires one or two platform companies in an industry and then makes a number of add-on “synergistic” acquisitions to build the company. The original platform sellers may or may not have a continuing ownership position in the consolidated company. The add-on company sellers probably will not have a continuing ownership position. With a recapitalization, some or all of the selling shareholders will have an ownership position in the consolidating company. Quite often the platform company in a buy-and-build strategy is recapitalized.

EXHIBIT 33.3 Transfer Matrix: Buy and Build and Recapitalizations

In a recapitalization, an owner sells part of the equity of the business in order to take some chips off the table while still operating the business. Recaps can involve the sale of any amount of company stock, but most involve a change of control. Most recap investors prefer to purchase at least 80% of the subject's stock at the outset. Doing so enables the investor to consolidate the subject's financial results to a holding company, which may have tax advantages to the investor.

Recaps can have numerous benefits. By employing a recap strategy, an owner hopes to achieve some or all of these goals:

- Increase personal liquidity.

- Continue operating the business while maintaining a significant equity position.

- Reduce personal risk by eliminating borrowing guarantees.

- Gain access to financial professionals who have experience in growing and exiting from businesses.

- Possibly receive nondiluting capital for growth. This last point is particularly important. In some cases owners are able to negotiate a provision whereby their equity is not diluted as more growth money is invested.

Mechanics

A typical change-of-control recap involves several steps. First, the subject is valued on an equity enterprise basis (100%). Recap valuations typically are conservative. Many recap investors value a company by applying no more than a five to six multiple against recast adjusted EBITDA, less long-term liabilities. Adjustments to EBITDA include seller discretionary items and one-time expenses. Potential deal synergies are not incorporated into the valuation.

Second, as part of the recap strategy, the original owner and the recap investor agree on a business plan for the recapped company (RecapCo) with fairly aggressive growth targets. This expansion usually is realized through a combination of one part organic growth and two parts add-on acquisitions. Recap investors normally expect to receive at least a 25% to 35% compounded rate of return on their investments, so the earnings growth of the RecapCo must be strong enough to support this return. The recap investor commits to fund the business plan, which may have a five- to seven-year horizon. Finally, the investor and original owner plan a liquidity event, usually near the end of the business planning period. This event could include a sale of the business or executing an initial public offering. Next we show the recap mechanics in more detail.

Example

Joe Mainstreet has been itching to do a deal for several chapters now. He sees tremendous growth opportunities for PrivateCo but does not want to give the company away for someone else to harvest the crop. Joe thinks a recapitalization may meet his needs.

Joe hires Dan Dealmaker to help market his company. Dan chooses a one-step private auction transfer process. Only PEGs are invited into the auction. Dan finds eight such groups, all of which are experienced players in the recap segment.

There are several key items that Dan negotiates with investors.

1. PrivateCo is valued on an all-cash basis.

2. The amount and type of funding that the recap investor will commit to the deal going forward.

3. The length of time and terms of Joe Mainstreet's employment agreement are considered.

4. What shareholder rights are available to Joe after the transfer as a minority shareholder? What decisions can he influence?

Dan Dealmaker supplies the equity groups with the next summarized information.

| PrivateCo Summary Financials | ||

| Book value (taken from Chapter 5) | $1.0 million | |

| Long-term debt | .5 million | |

| Net asset value (Chapter 5) | 2.4 million | |

| Benefit stream | ||

| Pretax earnings | $1.8 million | |

| Prior owner compensation | .45 million | |

| Prior owner discretionary expenses | .1 million | |

| Depreciation | .4 million | |

| Normalized capital expenditures | (.3) million | |

| Adjusted EBITDA | $2.45 million | |

Dan asks each equity group to incorporate into their offer all of the key transfer points just mentioned. His private auction process nets several offers. After six weeks of further negotiation, Dan negotiates the next term sheet with PEGCo.

With this deal, Joe receives $9.8 million at the close and does not guarantee any of the company's debts going forward. He receives a salary of $200,000 per year, with a bonus potential of another $75,000. Joe is not diluted unless he agrees to spend more than $10 million in growth capital. Finally, he has veto powers over all key board decisions. All in all, it is a pretty sweet deal. Joe wonders how PEGCo can afford such a deal and still meet its return expectations.

Once again, Dan Dealmaker has an explanation. Dan believes that PEGCo desires at least a 30% compounded return on its investments. During the negotiations, it comes to Dan's attention that PEGCo believes the following about RecapCo:

| PEGCo Return Calculation | |

| RecapCo earnings in year 5 | $ 5 million |

| Likely selling multiple | 5 |

| Likely selling price in year 5 | $25 million (debt-free) |

| Times PEGCo ownership % | 80% |

| Cash to PEGCo in year 5 | $20 million |

| PEGCo investment in deal | $4.8 million |

| Compounded return to PEGCo | 33% |

If RecapCo achieves its goal of earning $5 million in the fifth year and the company is sold for five times its earnings, PEGCo will earn a 33% compounded return on its investment.

This deal also works for Joe Mainstreet. He receives $9.8 million at the close, then $5 million more in year 5 ($25 million selling price times 20%). Along the way, he collects more than $1 million in compensation for doing what he loves.

There are now thousands of institutional recap investors in the U.S. marketplace. The majority of PEGs participate as recap investors. These investors break down by size. Most investors focus on recap investments of $2 million to $10 million, which represents the minimum size range for institutional support. Another group invests primarily in deals with transactions between $10 million to $50 million. Finally, a few hundred investment firms participate in transactions greater than $50 million.

RECAPITALIZATION POINTS TO CONSIDER

A recapitalization is a complicated financial technique that should be used only if fully understood. The next points may help.

- The subject's shareholders can choose individually whether to cash out or retain an equity position in the recapitalized company. A shareholder can receive a mix of cash and continuing ownership.

- Few managers have the vision and management ability to navigate a recapitalization successfully. Owners need professional help in this area.

- PEGs are constantly on the lookout for owners who have the right combination of industry knowledge and hypergrowth management ability. Many successful recap managers have executive experience with a large company prior to transiting to an ownership role.

- Too much leverage used in a recap is a dangerous thing. Most recap investors use substantially more debt than equity in the recapitalization. Owners should require a conservative capital structure in the recap. This means employing a debt-to-equity ratio of no more than 2.5:1.

- Owners should team only with experienced recap investors. A recap investor needs experience and savvy in guiding aggressive growth plans and creating maximizing exits. It behooves an owner to interview at least six to eight investors before selecting one.

- The valuation of the subject and cash received up front by the owner are the two items that draw the most attention. As with management transfers, the terms of the deal are as important as valuation and price. If an owner is to be successful in the recap, shareholder rights issues, employment agreements, and future funding commitments must be considered.

Recaps are not for everyone. If selling a business once is not enough for an owner, however, a recap just might be the answer.

TRIANGULATION

To be successful, consolidators must understand how to value and capitalize acquisition opportunities. Buying in one value world and selling in another often creates value. For instance, most consolidators attempt to acquire in the financial subworld of market value and exit either in the synergy subworld of market value or through the public markets.

Some of the most successful consolidations involve buying groups of companies in the asset subworld, merging them into an operating company, and selling out to one of the higher-value worlds. Once critical mass is achieved, the exit can occur in the synergy subworld. Exiting at this level gives the consolidator a slightly higher selling multiple plus a higher synergized benefit stream. This is the logic behind recapitalizations.

Of course, consolidators need constant access to capital. Roll-ups access capital directly from the public capital markets. This is an insider's game with few acquirers having the Wall Street contacts to execute this strategy. The more likely consolidation is the buy and build version; hundreds of PEGs are ready to play this game. PEGs are capable of employing sophisticated capital structures to support their deals. For example, it is not unusual for PEGs to support their equity investment with senior lending and mezzanine capital. Manipulating capital structure is a critical success factor for consolidating companies.

NOTE

1. Keith Brown, Amy Dittmar, and Henri Servaes, “Roll-ups: Performance and Incentives for Industry-Consolidating IPOs,” abstract, March 2001.